What is Writing to Engage?

Contents

Getting Started

Why include writing in my courses?

What is writing in the disciplines?

Useful Knowledge

What should I know about rhetorical situations?

Do I have to be an expert in grammar to assign writing?

What should I know about genre and design?

What should I know about second-language writing?

What teaching resources are available?

What should I know about WAC and graduate education?

Assigning Writing

What makes a good writing assignment?

How can I avoid getting lousy student writing?

What benefits might reflective writing have for my students?

Using Peer Review

Why consider collaborative writing assignments?

Do writing and peer review take up too much class time?

How can I get the most out of peer review?

Responding to Writing

How can I handle responding to student writing?

How can writing centers support writing in my courses?

What writing resources are available for my students?

Using Technology

How can computer technologies support writing in my classes?

Designing and Assessing WAC Programs

What designs are typical for WAC programs?

How can WAC programs be assessed?

More on WAC

Writing to engage stands between the two most common approaches to writing across the curriculum: writing to learn and writing in the disciplines (sometimes referred to as writing to communicate).

Writing to engage relies on viewing writing as a means of engaging students in critical thinking. Certainly, writing has long been viewed as a useful means of demonstrating critical thinking and, through the work of scholars such as Marlene Scardamalia and Carl Bereiter (1987), even as a means of transforming knowledge. Writing to engage takes this view of writing and applies it to WAC.

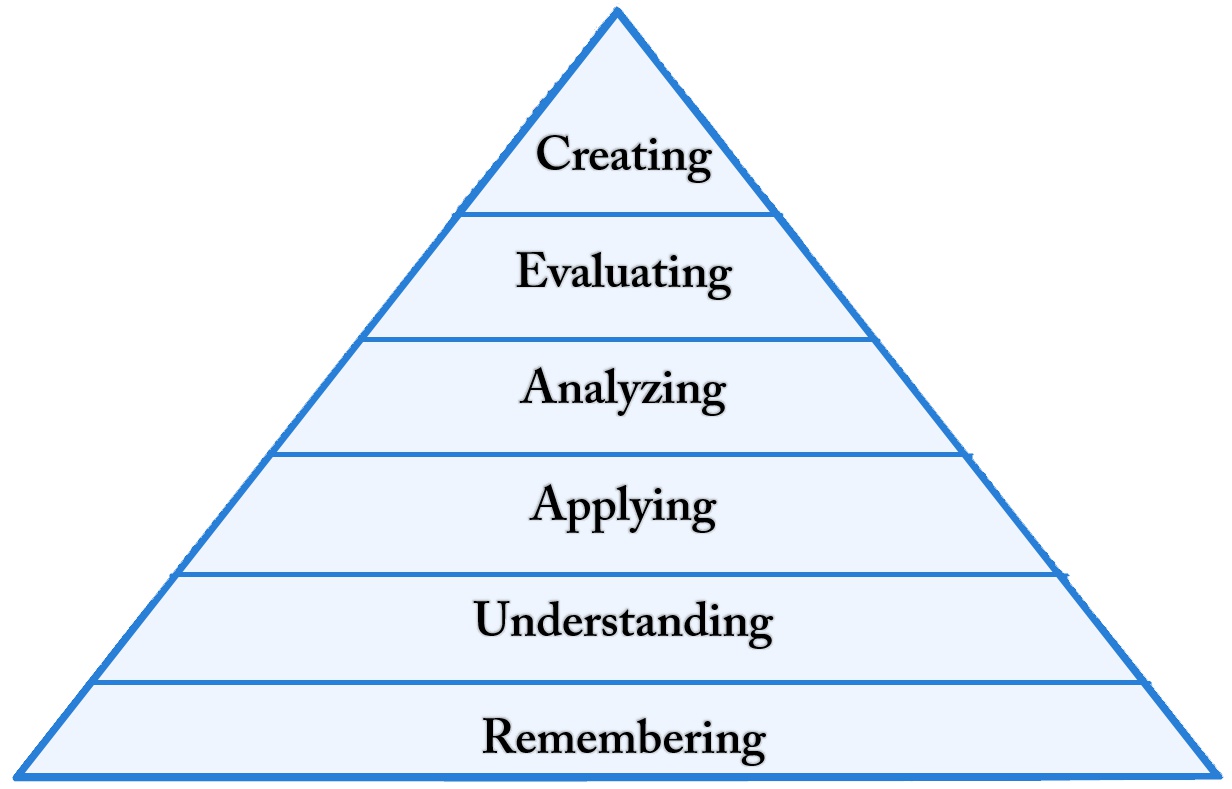

As with any educational approach, there is a great deal of variance in how to approach writing to engage. John Bean, in his book Engaging Ideas: The Professor's Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom, approaches the idea of linking writing and critical thinking through what might be characterized as a problem-solving approach to critical thinking. In this guide, in contrast, we view writing to engage through the lens of Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives. The taxonomy, originally developed in the 1950s, was modified by Lorin Anderson and David R. Krathwohl and their colleagues in 2001 to include a more accessible set of terms for describing learning objectives in the cognitive domain.

Beginning in the 2000s, Mike Palmquist's work with teaching and learning initiatives at Colorado State University led him to begin considering writing to engage as a set of activities that stands between writing to learn and writing in the disciplines. He viewed the three activities as standing along a spectrum and as overlapping. You can read a more complete consideration of writing to engage in two works available through the WAC Clearinghouse:

- Mike Palmquist. (2020). A Middle Way for WAC: Writing to Engage. The WAC Journal, 31. https://doi.org/10.37514/WAC-J.2020.31.1.01

- Mike Palmquist. (2021). WAC and Critical Thinking: Exploring Productive Relationships. In Bruce Morrison, Julia Chen, Linda Lin, & Alan Urmston (Eds.). English Across the Curriculum: Voices from Around the World (pp. 207-222). The WAC Clearinghouse; University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.37514/INT-B.2021.1220.2.11

A Brief Discussion of Writing to Engage

Our approach to writing to engage relies heavily on the idea that students can benefit from engaging in writing activities that help students work with and develop greater control of the concepts, conceptual frameworks, skills, processes, and issues addressed in a course. Following the work of Bloom and his colleagues, we view the kinds of thinking in which we hope to engage students as:

- Remembering

- Understanding

- Applying

- Analyzing

- Evaluating

- Creating

While these activities are often viewed as increasing in complexity, it is important to note that Bloom and his colleagues presented these activities as a taxonomy and not as a hierarchy. Nonetheless, Bloom's taxonomy has typically been presented in a form of a pyramid, with remembering (initially "knowledge" in the early publication of Bloom's taxonomy) and understanding (initially "comprehension) at the bottom and evaluating and creating (initially "synthesis" and "evaluation") at the top.

Bloom's Taxonomy, as modified by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001).

Because hierarchies tend to imply value, Bloom's taxonomy is sometimes presented in terms of "higher order" and "lower order" thinking skills. (For an example, see the higher-order thinking chapter in the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development book, Literacy Strategies for Grades 4–12: Reinforcing the Threads of Reading). Viewed as a taxonomy, in contrast, we see these types of thinking as value neutral. One might ask, for example, whether it is more useful to understand a complex knowledge domain such as genetic engineering or to create a limerick (and we might add that we intend no disparagement of limericks; indeed, we find great pleasure in them).

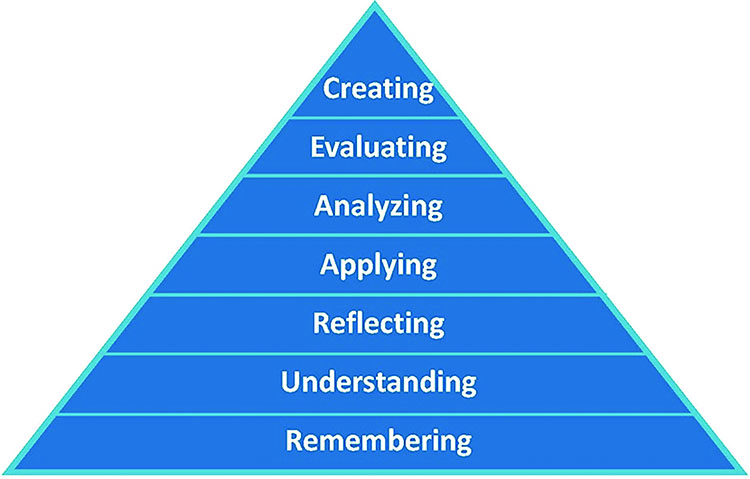

We also recognize that Bloom's taxonomy, in its original and modified forms, does not necessarily include all the critical thinking activities that would be viewed as important by teachers who use writing in their courses. Palmquist, for example, has added reflection as a key critical thinking skill, placing it between understanding and applying.

Bloom's Taxonomy, modified again to include reflection (Palmquist, 2020).

Following Bloom's taxonomy, we characterize writing to learn, writing to engage, and writing to communicate (writing in the disciplines) as focusing on different parts of Bloom's taxonomy:

WAC activities and assignments are aligned along a spectrum of critical thinking skills (Palmquist, 2020)

Examples of Writing-to-Engage Activities

We've seen a wide range of activities that can be used to support writing to engage. For example, a colleague in sociology created an assignment in which students viewed a video on YouTube, wrote a summary of the video that called out salient elements in terms of their previous class discussions, selected one of three conceptual frameworks to apply to the situation presented in the video, briefly applied the conceptual framework and recorded their findings, and then explained their decision to choose one conceptual framework instead of one of the others. The assignment was designed to be about three pages in length and students were provided with an outline that they could follow as they planned their document.

You might consider several types of writing-to-engage activities, including the following:

- Application of Frameworks to Texts, Media, or Cases

- Evaluations of Alternative Approaches and Methods

- Reflections

- Critiques

- Comparisons

- Proposals

- Brief Reports

- Progress Reports

References

Anderson, Lorin W., & Krathwohl, David R., et al. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Bean, John C. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom (2nd ed). Jossey-Bass.

Palmquist, Mike. (2020). A middle way for WAC: Writing to engage. The WAC Journal, 31. https://doi.org/10.37514/WAC-J.2020.31.1.01

Palmquist, Mike. (2021). WAC and critical thinking: Exploring productive relationships. In Bruce Morrison, Julia Chen, Linda Lin, & Alan Urmston (Eds.). English Across the Curriculum: Voices from Around the World (pp. 207-222). The WAC Clearinghouse; University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.37514/INT-B.2021.1220.2.11

Scardamalia, Marlene, & Bereiter, Carl. (1987). Knowledge telling and knowledge transforming in written composition. In S. Rosenberg (Ed.), Cambridge monographs and texts in applied psycholinguistics. Advances in applied psycholinguistics, Vol. 1. Disorders of first-language development; Vol. 2. Reading, writing, and language learning (pp. 142–175). Cambridge University Press