Deconstructing and Reconstructing Genre and Form with Tracery

Mark Sample

Davidson College

In this assignment, students work with HTML, CSS, Javascript, and JSON templates in order to design a website that generates new content out of pre-established rules and word banks. No prior coding or web development experience is required; the free browser-based platform Glitch.com hosts the projects templates as well as the projects themselves. The assignment encourages students to deconstruct the underlying rules, tropes, and conventions of any kind of textual genre. This assignment emerged out of an undergraduate course devoted to digital literature and poetry, but it can be adapted for many contexts, including any field concerned with form, style, and genre conventions.

Learning Goals:

- Deconstruct some genre of text by identifying that genre’s underlying rules, tropes, and conventions.

- Reconstruct that genre of text using a combination of randomness and curated content.

- Create an original multimodal work that takes advantage of the unique aesthetic and literary affordances of digital environments.

- Understand how Tracery grammars—and combinatory writing more generally—work.

- Develop an appreciation for the exponential power of combinatory writing, which can generate billions of variations while simultaneously working with various constraints.

Original Assignment Context: Middle of elective digital studies course

Materials Needed: Web-based HTML, CSS, Javascript, and JSON templates (linked in assignment), a free account on glitch.com

Time Frame: ~4-5 weeks

Introduction

Deconstructing and Reconstructing Genre and Form with Tracery is an assignment in Digital Studies (DIG) 220: Electronic Literature, a course in the Digital Studies program at Davidson College. DIG 220 surveys the past and present of interactive narrative, digital poetry, and hypertext fiction—collectively known as electronic literature, or e-lit. Given its focus on narrative and aesthetics, the course also counts for the English major and minor at Davidson College. The class draws a mix of students, ranging from English majors who have never coded in their life to Computer Science majors who are more comfortable with Python than poetry. In between are students simply seeking to fulfill Davidson’s Literary Studies, Creative Writing, and Rhetoric “Ways of Knowing” graduation requirement, our version of a literary-oriented general education requirement. The class size is typically 25-30 students, representing every year from first-year students to seniors. I’ve taught the course three times over the past few years, and I’ve used this particular assignment in the past two iterations of the courses. I also use a variation of this project when I teach creative coding workshops for grad students and faculty. Which is to say, the project works well at nearly every level.

Most electronic literature courses follow one of two organizational models. The first model is chronological, marching through digital poetry and narrative of the past half century. This model is often teleological, suggesting that early “primitive” works of digital literature eventually gave way to more complex contemporary works, a notion that doesn’t strictly hold up. The second model is platform-based, which tends to stress technological affordances of tools like Storyspace, Inform, Flash, or Twine at the expense of other aesthetic values. The organizing principle of my course eschews both chronology and platforms. Rather, the course is organized around broad literary and aesthetic themes, such as the uncanny, the sublime, or dysfunction. This organization puts e-lit works from entirely different eras and modes of production into conversation with each other. Furthermore, it actively undermines any technological determinism that my students—and honestly, I—might bring to the material.

Students tackle the Deconstructing and Reconstructing Genre and Form project in a unit on randomness and variability. It is here we delve into the history and power of combinatory writing, which mashes up texts with a degree of randomness, yet is still constrained by a “grammar” or controlled vocabulary. By this point in the semester, students will have encountered digital poets such as Allison Knowles, Nick Montfort, Stephanie Strickland, Amaranth Borsuk, and others who have produced profound work using what at first glance seems to be Mad Libs on steroids. That is, a template or scaffold of syntactical structure the blank spots of which are filled in procedurally with words and phrases curated by the writer/programmer.

Anyone familiar with Mad Libs knows that this kind of combinatory writing lends itself to parody, satire, and outright absurdity. Yet, combinatory writing is also a powerful tool for understanding how genre and form work. Pick any genre of short form nonfiction —horoscopes, menus, movie recaps, medical bills, emails, diaries, and so on—and one finds certain rules, tropes, and conventions at work. In order to make an approximation of such writing convincing, one must study the form, breaking it down to its constituent parts and diving deep into its underlying rhetorical, paradigmatic, and syntagmatic strategies. This is the deconstructing part of the assignment. Without a doubt, taking apart a text is the best way to figure out how it works. This is doubly true when it comes to genre writing. This approach to understanding texts is heavily influenced by Jerome McGann and Lisa Samuel’s concept of “deformance,” a portmanteau of performance and deform. For McGann and Samuels, a deformance is an interpretive strategy premised upon deliberately misreading a text, for example, reading a poem backwards line-by-line. As Samuels and McGann put it, reading backwards “short circuits” our usual way of reading a text and “reinstalls the text—any text, prose or verse—as a performative event, a made thing” (Samuels & McGann 30). Reading backwards revitalizes a text, revealing its constructedness, its seams, edges, and working parts. So too does trying to recreate formulaic writing through procedural generation.

As I said, procedural generation lends itself to parody. For example, creating an endless procedurally generated horoscope that makes fun of the tropes of horoscopes is a rather simple matter. More difficult to achieve with procedural generation is writing that evokes genuine emotion or narrative insight. And this is ultimately what I challenge my students to do: produce generative writing that offers insight and critique. Our goal is not merely to create a procedurally generated text that is funny or absurd, but to create procedurally generated texts that take a stance, point a finger, examine the world.

To that end, students work on a generative text project using Tracery, a Javascript library that lowers the barrier to creating with the “slotted” technique of combinatory writing. Here is the general flow of the assignment:

- We study existing examples of procedural writing that offer both satirical and more substantive critiques of the world.

- Students learned the basics of Tracery through in-class workshops.

- Students experiment with a “starter” template of a fully functional Tracery project via glitch.com, which makes it easy to work on HTML, Javascript, and CSS directly in a browser, without special text editors or development tools.

- Finally, I introduce the assignment itself, including what at first seems like its impossible criteria, such as developing a project that has at least 1 billion possible variations.

Generally students have several weeks to work on the project, including at least one day in-class, where I can help troubleshoot problems or push students out of their comfort zone with CSS and HTML. Because the students work in glitch.com, their projects are easily shareable, and we’ll have a brief show-and-tell at the end of the project where they share and critique each other’s work.

Goals and Outcomes

This Tracery project serves several learning goals. By the end of the project, students will be able to do the following:

- Deconstruct some genre of text by identifying that genre’s underlying rules, tropes, and conventions.

- Reconstruct that genre of text using a combination of randomness and curated content.

- Create an original multimodal work that takes advantage of the unique aesthetic and literary affordances of digital environments.

- Understand how Tracery grammars—and combinatory writing more generally—work.

- Develop an appreciation for the exponential power of combinatory writing, which can generate billions of variations while simultaneously working with various constraints.

Materials Needed

The work for this project can be done entirely in any modern web browser, such as Chrome or Firefox. Students will need a free account on glitch.com.

Acknowledgments

There are three foundational inspirations for this project. First, the work of Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann: “Deformance and Interpretation” from New Literary History, vol. 30, no. 1, Jan. 1999, pp. 25–56. Second, the creative and pedagogical work of Nick Montfort, who advocates for what he calls “exploratory programming” and who makes his own work open and available for remixing, adaptation, and reuse (see Montfort’s open access edition of Exploratory Programming for the Arts and Humanities, second edition, published by MIT Press in 2021). The third inspiration is more theoretical: Sianne Ngai’s concept of stuplimity, which she describes as a “mixture of shock and exhaustion” in the face of stupefying quantities of more or less the same thing—an aesthetic quality that applies to many procedurally generated combinatory texts (see Ngai’s Ugly Feelings, Harvard University Press, 2005). And of course, this project would also be impossible without Kate Compton’s Tracery library and Allison Parrish’s port of Tracery into Python.

The Assignment

Overview

For this project you’ll use a variation of the “slotted” technique of combinatory writing. This means building sentence templates with empty slots for nouns, verbs, and so on. A program then randomly selects from pre-selected lists of words to fill each slot. Think of procedural generation as Mad Libs gone crazy. Tracery is the procedural engine you’ll use. It’s a Javascript library by Kate Compton that lets you create surprising configurations of texts out of the template (called “grammar”) and vocabulary you provide.

Strictly speaking, this project does not involve programming. It does, however, require procedural thinking. Every Tracery grammar takes the form of JSON data. This is a highly structured text format that both humans and computers can “read”—though parse might be a better word. Your grammar data file tells Tracery what your templates are (templates in the plural because you can embed templates within templates recursively) and provides the vocabulary for Tracery to use as it fills in the templates.

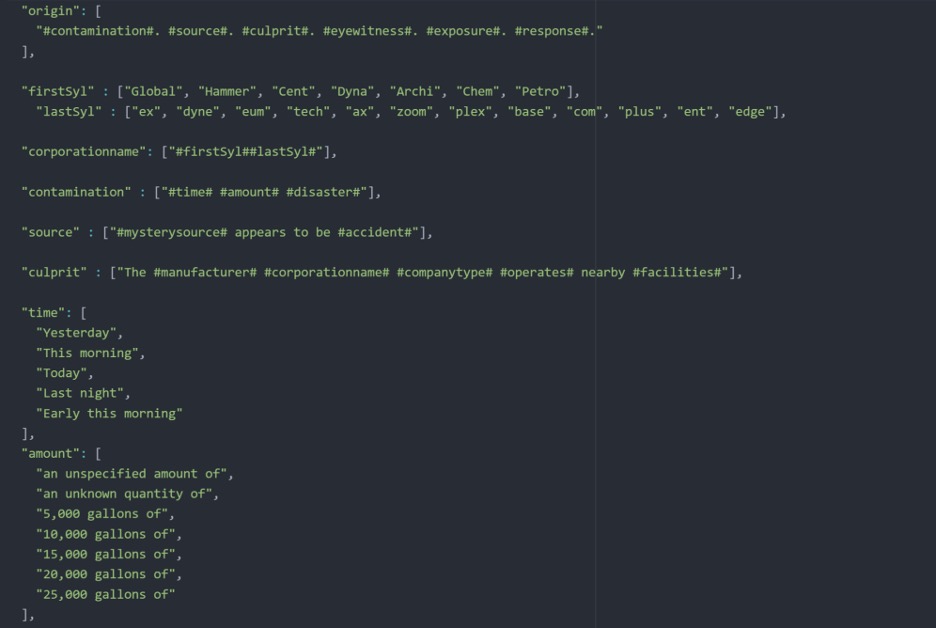

The Tracery grammar JSON that powers Don’t Drink the Water”

It’s easy for text generation to be comical or satirical, like Nora Reed’s thinkpiecebot or Compton’s Night Vale Generator, both of which use Tracery. Other text generation parodies powered by tools similar to Tracery include the Postmodern Essay Generator and Eric Drass’s machine imagined art.

It’s also possible to make text generators that are serious or provide social critique, such as my own Infinite Catalog of Crushed Dreams or Leonardo Flores’ Tiny Protests bot, which both use Tracery or Tracery-like tools.

Guidelines

- Decide what kind of text you want to generate. Will it be a parody? Social commentary? A genre, like horror, romance, or science fiction? Fake non-fiction? What’s the mood of the work? Humorous? Sarcastic? Somber or melancholy? Whatever it is, strive to give it some depth.

- Make an account on Glitch and clone the template files from “Don’t Drink the Water.” Glitch is a community of creative coders that provides free online tools and hosting. Once you’ve remixed the project you can edit your own version directly in your browser. You can instantly see the results by clicking the “Show Next to the Code” option in Glitch (click the sunglasses). Also check out my tips on customizing the look of your project.

- Go through the Tracery tutorials below as you work on your project. When you first start it might help to use a visual editor. Beware that these editors are liable to crash as your grammar grows in complexity. You can paste the code from the visual editor into Glitch. See also my Tracery Tips for more details on working with Tracery.

- You will also write an Artist Statement that puts your Tracery project in dialogue with questions regarding combinatory writing, procedural generation, novelty and repetition, authorship, and creativity.

More Details on Editing Tracery

- To actually edit the underlying Tracery grammar, edit the grammar.js file in Glitch. You can also paste the text of grammar.js into the online Tracery editor to make sure it’s working.

- If the page is entirely blank in your browser, then there’s an error in your grammar.json file! Go back and make sure all your commas and so on are in place.

- In addition to editing the grammar.js file, you should edit the index.html file (you can do this in Glitch too) and update it to reflect your own project’s needs. You can also edit the style.css file in order to change fonts, font sizes, colors, and other visual elements of the page.

Criteria

DIG 220 uses an assessment method called specifications grading. In specifications grading, expectations for projects are clearly laid out, and you either meet the criteria or you don’t. If you don’t, you’ll have an opportunity to revisit the work and revise it so that it does meet the criteria.

These are the minimal requirements for the project to be considered for a B-range grade.

- Your Tracery project must have at least 1,000,000 possible combinations.

- 9 out of 10 combinations must parse correctly. That is, at least 9 out of 10 combinations should make grammatical sense, though not necessarily logical sense.

- The Tracery project is accompanied by a 750-1000 word Artist Statement. You’ll share the Artist Statement with me as a Google Doc and also post the link on Moodle

- The Artist Statement must integrate at least two secondary sources in a substantive way. “Substantive” doesn’t mean merely quoting at length or cherry-picking a key phrase. “Substantive” means actively engaging with the source by (1) summarizing its overall argument; (2) showing how that argument ignores important issues, doesn’t go far enough, or could be applied to new contexts; and (3) applying concepts from the secondary source to your procedurally-generated text. See below for possible secondary sources to consider.

- The Artist Statement follows scholarly standards for citation, using either MLA, APA, or Chicago style.

- The Artist Statement contains no more than 3 grammatical, spelling, or other “mechanical” errors. It also contains no more than 2 minor factual inaccuracies and no major factual inaccuracies.

- You must also post a working link to your Tracery Project on the class blog, under the category “Tracery Project.” Include a 2-3 sentence description of the project, as well as its name.

- The Tracery project and Artist Statement are shared by class time on Friday, March 13.

To be considered for an A-range grade, you project must meet the above criteria plus the following:

- Your Tracery project must have at least 1,000,000,000 possible combinations.

- The generated text should do more than provide a few minutes worth of entertainment. It should be something compelling enough that a reader wants to keep reloading even after the initial novelty has worn off. Make it provocative, evocative.

- The generated text should be longer than a few paragraphs (prose) or stanzas (poetry). As a point of comparison, Don’t Drink the Water would need at least two more paragraphs to meet this criteria.

- You must customize the look of your project in meaningful ways. That is, in ways that noticeably contribute to (rather than detract from) the visual style of the project. Font sizes, color changes, even changing the font could conceivably be meaningful changes to make. I’ve provided some tips on styling Tracery.

- The Artist Statement must integrate at least one more secondary source in a substantive way (so, a total of three sources).

- The Artist Statement uses more effective logic, rhetoric, and style to advance its argument.

Key Modifiers in Tracery

- Adding .a to a rule will cause the right “a” or “an” article to appear, for example #noun.a#

- Adding .capitalize to a rule will capitalize the word

- Adding .s to a rule will pluralize it, e.g. #noun.s#

- Adding .ed to a rule will make a verb past tense. Obviously, use #verb.ed# only with verbs!

Validating Your Grammar

Pasting your grammar JSON file into https://jsonlint.com is a good way to quickly find missing or extra commas, brackets, or quotations that will screw up Tracery.

Your grammar is everything between the two curly-que brackets: { }

But in order for index.html to load you grammar you need to make sure your grammar file itself has the line

var grammar =

at the top. Then the curly que brackets and everything in between should appear.

Common Errors

- Missing commas between items in list

- An extra comma after the last item in a list

- Rule names with spaces, like #my noun#

Tutorials and Tools

There are a host of Tracery tutorials out there, but the best are the following:

- Kate Compton’s Tracery tutorial

- Allison Parrish’s Tracery tutorial

- My tips on working in Tracery

- My tips on styling Tracery

Some useful tools include:

- Beau Gunderson’s Tracery writer

- Kate Compton’s Tracery visual editor

Possible Secondary Sources

In addition to Scott Rettberg’s Electronic Literature, here are some other sources you might want to consult as you work on your Artist’s Statement:

- Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author” from Image-Music-Text

- William S. Burroughs, “The Cut-Up Method of Brion Gysin” from The New Media Reader (2003)

- Chris Funkhouser, “First Generation Poetry Generators” from Mainframe Experimentalism: Early Computing and the Foundations of the Digital Arts (2012)

- Charles Hartman, Virtual Muse: Experiments in Computer Poetry (1996)

- Margaret Masterman, “The Use of Computers to Make Semantic Models of Language” from Astronauts of Inner-Space (1966)

- Mark Marino, “Critical Code Studies” from Electronic Book Review (2006)

- Janet Murray, chapter 3 from Hamlet on the Holodeck (1997)

- Sianne Ngai, “Stuplimity” from Ugly Feelings (2005)

- Noah Wardrip-Fruin, “Five Elements of Digital Literature” from Reading Moving Letters: Digital Literature in Research and Teaching (2010), pp. 29–57