Reading the World Wide Web

Contents

This guide provides a brief overview of the processes involved in reading the web. Developed in the late 1990s, while the web was still a relatively new and rapidly changing environment, it continues to offer useful insights into the challenges of reading documents intended for delivery on the web.

How Web Documents Differ from Print Documents

Though Web documents are similar to print documents in many ways there are some key differences that you should be aware of in order to become a better reader of Web material.

Associative Structures

Texts on the Web are structured in a more associative manner than traditional print texts. Information is displayed using nodes and links. A node is a chunk of information. it may be a page, a paragraph, a sentence, or a character. A node can even be a graphic. A link is a connection between nodes. You will often see links represented in blue underlined text that turns purple after you visit that link, these are the default colors. links will not always appear this way, often times links are buttons or graphics.

There are three basic structures of links and nodes that Web documents usually follow. Every document may not resemble wholly one of these structures but may contain elements of any number of these structures.

Linear Structures

A linear structure is much like turning th pages of a book, you can move through the text in two directions forward and backwards. Nodes and links are arranged in a linear pattern.

This is a model of a linear strucutre.

N— N— N— N— N— N

"N" represents a node and "—" represents a link.

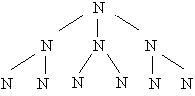

Hierarchic Structures

A hierarchic structure

This is a model of a heirarchic strucutre.

"N" represents a node and "—" represents a link.

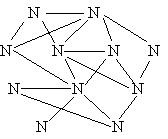

Web-like Structures

A Web-like structure has no apparent structure. Nodes may be linked to a variety of other nodes. If you imagine each node as a particular Web-site, the World Wide Web is structured this way.

This is a model of a Web-like strucutre.

"N" represents a node and "—" represents a link.

Web Documents are Highly Interactive

Not to say that searching the library or picking up the phone is not interactive, but within Web documents everything is at your fingertips. And you, the reader, have far greater control over how the interaction takes place. Imagine being in the library and having to go from the West wing on the third floor to the south wing in the basement, with the Web you could be at the library at Oxford looking at the Canterbury Tales before you could make it downstairs.

Web Documents are More Navigable

Web documents contain built in navigational features. The Web encourages and supports movement to other pieces information in multiple directions. For instance to access information quickly in a book you look in the index and then flip to any of a number of pages, if the information you seek is not on that page you go back to the index and repeat the process and until you find what you're looking for. With the Web this process is condensed significantly, you can "flip" pages instantaneously with a click of the mouse.

Web Documents Contain an Abundance of Graphics

When reading the Web you have to deal with a large amount of graphics. You're likely familiar with ads, photos, tables, and figures; but what about icons, buttons, thumbnails, mouse-overs, or virtual reality.

Icons

Web documents often use icons to represent some sort of functionality. For instance on your desktop the icon for Microsoft Word is a piece of paper that represents the word processor.

Buttons

Buttons are often used as graphical links, when you click on them you go somewhere else. For instance the graphic in the top right hand corner of this frame is a button that allows you to go back to the Graphics overveiw page.

Menu bars

Menu bars are a collection of buttons that usually contain key links within the site. For example the menu bar on the bottom of this page contains buttons that link to the homepage, the sitemap, the index, help, etc.

Thumbnails

Thumbnails are small versions of graphic that when clicked on produce larger versions of the graphic. The smaller file size of thumbnails allows them to be loaded more quickly and saves space on the page for other information. Thumbnails also allow you a quick view at a graphic and the choice to view it in more detail if you wish.

Mouse-overs

Have you ever noticed a change in a graphic when you move your mouse over it? Mouse-overs are used mainly to draw attention to where your mouse is on the screen, but they also may highlight other features. For example run your mouse over the menu bar at the bottom of this page. You will notice that the button your mouse is over changes from gold to blue when your mouse is over it.

Virtual Reality

Virtualy Reality is a three dimensional graphical representation on your screen. When viewing virtual reality you move through the space just as you would in say a three dimensional video game. You might have to open doors or retrieve objects, to get the information you are looking for.

The Web is a Vast Document

Some say that the entire Web is a single document. The Web grows by the day increasing the size of the document exponentially. The amount of information on the Web far exceeds what the largest library in the world could hold in print. This has advantages and disadvantages for the Web reader. The Web contains a great deal of useful information that is easily accessible while at the same time there is quite a bit of distracting information.

How We Read the World Wide Web

When reading the Web you have strong Critical Reading skills. When reading online we use clues from the text to decode messages just as we do when reading print. Web documents use many of the same clues you'll find when reading print and a few new ones. Knowing what these new clues are and how to Web readers ues them can make your online reading experience more enjoyable and more productive.

What the Web Adapted from Print

Web documents utilize design techniques from print, graphics, video, and more. As readers we tend to take many of the textual clues in print for granted because we are so used to them. Many of these clues are used in Web documents—they will likely appear familiar to you but there may be some subtle differences in how they are used that you should be aware of.

Titles

Yes, something as simple as the title can tell you quite a bit about the document. Sometimes you can decide whether or not to read further based on the title alone.

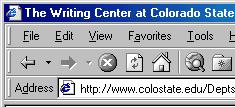

In Web documents look for the title at the top of any page, but also look at the title bar at the top of your screen. The blue section in the graphic below is the title bar, it lets you know that you are at "The Writing Center at Colorado State."

Indexes

Many Web sites will have a site index just as you would find in a book. Web site indices would likely include a search function. In many Web indices you will see an arrangement of the letters of the alphabet somewhere on the page, if you click on one of the letters you will go directly to that section of the index without having to scroll to it.

Lists

Web documents use lists to display information beacuse Web readers prefer to scan for information rather than read dense passages of information. Look for bulleted or numbered lists that highlight important information.

Highlighting

Highlighting is anything that calls attention to a piece of text. Common highlighting techniques are bolding, italicizing, and underlining.

These common highlighting techniques are used slightly different on the Web: bolding will likely be accomplished by a change in font size, italics are rarely used, and underlining is generally reserved for links.

Other highlighting techniques that are used on the Web include color and graphics.

What's New When Reading the Web

The multimedia nature and computer interface of the Web enables it to offer the reader more assistance in finding the information they need than print documents can. Knowledge of the features presented here will help you locate information quickly within a site and remeber where you are.

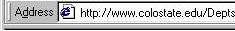

URL's—Web addresses

URL's— Universal Resource Locators— are Web addresses. Every Web page has its own URL. You're probably familiar with URL's, they look like this: http://www.colostate.edu/ You can find the URL of a page in the address bar of your browser.

If you want to remeber the exact location of a page be sure to record the entire URL.

The URL can reveal quite a bit of useful information about the Web site, information you need to determine how well the site meets your needs: http://www.colostate.edu/index.html

- http: is the protocol, it tells the computer how to interpret the page

- www is the host of the site

- colostate is the directory that the page is in

- .edu is the type of site it is (educational)

- .com is a commercial site

- .gov is a government site

- .org is a non-profit site

- index.html is the particular Web page you are at

Site Maps

Site maps are rather self explanatory, nevertheless a helpful feature of many Web sites that you may not be aware of. A site map is a graphical representation of the site. It will tell you where particular sections ar pages are found within the site.

Click on the "site map" button on the bottom of this page to view the site map of the Writing Center. The "previous" button on the top left hand corner of the site map will bring you back here.

Search

Many large Web sites will contain search functions. You are probably familiar with search engines such as Yahoo! or Google. A search engine within a site does just what one of the larger search engines does only the search is limited to inside the site.

Search functions can be very helpful if you are looking for a specific piece of information within a large site.

Frames

Frames break up the document into multiple areas. This site is displayed using frames: this window appears in the right frame, the overview in the left frame, and the menu in the bottom frame. Notice that the menu bar never changes as you move through the site—this is possible because of frames.

When reading documents displayed in frames try to figure out the pattern that the information is displayed in. More often than not there will be a menu bar or other functional area that stays with you as you move through the site, they are helpful in navigating the site and in avoiding getting lost.

Functional Areas

Functional areas are a part of the screen that serves a particular use. Functional areas may include menus, forms, toolbars, etc. Functional areas are helpful places to look when you are lost. Well designed functional areas will be consistent throughout the site.

-

Headers, Footers, Side Bars

Many times you will find key information pertaining to a site in areas you would consider a header or footer in a print document. Similarly in Web pages you might find key information in a side bar. Look to the top and bottom of the page or the top and bottom of your screen and along both sides for menu items, important links and important information about the site.

-

Menu bars

Menu bars are a collection of buttons that usually contain key links within the site. For example the menu bar on the bottom of this page contains buttons that link to the homepage, the sitemap, the index, help, etc.

-

Tool bars

You're likely familiar with tool bars in the software that you use—a group of buttons that each allow you to preform a function. Though less common in Web pages, you may still encounter them and if they are present they may be helpful in using the site.

-

Forms

Everyone has filled out forms, but forms on the Web allow a sort of interaction that was not possible with print. Web forms are generally processed immediately. you may have to fill out forms to make requests or subscirbe to a site or to post a message. If you encounter a form make sure you are aware of the results before you submit your information and do not give out important information about yourself casually.

The Successful Web Reader

Just as with print, we read on the Web for a variety of reasons. We may be on the Web to carelessly surf and entertain ourselves, or to find some needed piece of information, or to interact with people and texts around the world. While the following criterea for success apply mainly to the Web reader in search of information you may find them helpful in other ways as well.

Synthesize, Associate, Connect!

To suceed on the Web you have to think like a Web page. Information is not stored or presented in a linear manner, you've got to be willing to think associatively—what connections can you make between the text you are reading and a text that may contain the information you are looking for? or a piece of text that you just read?

You've got to synthesize material quickly. You'll be swamped with information on the Web, be prepared to evaluate information and decide how it meets or does not meet your needs. Where does this or that piece of information fit into the schema of your work? or your play?

Don't Read Unless You Have To— Scan

There's just too much information on the Web to waste time reading unless you really need to be. Learn to scan Web pages to locate the information you need. Look for key information in bulleted lists, menu bars, and other functional areas. Focus in on highlighting techniques that may lead you to key information.

Distracted— To Be or Not To Be

You may be carelessly surfing the Web for pure entertainment, but if you have a goal in mind do your best to stick to it. The Web is full of distractions such as advertisements, links to this and that, etc. You may find something of use if you wander a bit, but you also could get hopelessly lost. Some would argue that the distractions are what makes the Web great, but it comes down to what is your purpose for being there.

Critical Linking

You may be one who enjoys surprise, but if you looking hard for an elusive piece of information surprise is not what you need. Most well designed links will let you know to some degree what to expect when you click on them as will they give you a way to get back once you've gone. Know before you go is a good rule to follow.

Where Am I and How Did I Get Here?

Being lost on the Web is not as life threatening as being lost in the woods, but it can be equally frustrating at times. Do your best to avoid that lost feeling and the insuing panic. Many of the tips in the Strategies for online reading section help with knowing where you are including using the history function on your browser, using site maps, and menu bars.

Strategies for effective reading on the World Wide Web

Reading the Web takes some getting used to. Just remember with every visit to the Web you will become a better reader of online material—practice makes perfect.

- Be a confident online reader

- Making your browser work for you

- Getting the most out of the site

Be a confident Web reader

When reading on the Web it helps tremendously to be a calm and confident reader. Avoid panic and frustration and concentrate on fixing any problems you may encounter with a clear head. The more patient you are the more you will learn. Each time you surf the Web you will become better at it. Think of how comfortable you are reading a book, that comfort level has developed over many years as will your comfort level with reading online.

Making your Browser Work for You

Your browser is your way into the Web. Netscape Communicator and Microsoft Internet Explorer are the two most popular Web browsers. To make the most out of your visits to the Web take advantage of the built in functionality of your browser. The following list offers some simple suggestions to make your browser work for you.

Histories

Both Netscape and Microsoft incorporate History functions into their browsers. A history is a list of the Web pages you have visited. If you get lost or wish to go back to a page you were previously at check the history list for where you want to be.

Favorites/bookmarks

Both browsers allow you to mark and save a list of Web pages that you find useful or entertaining, in Netscape they're called "bookmarks" and in Internet Explorer they're called "favorites." Creating a list of bookmarks or favorites is a handy tool especially when you visit sites frequently and want to get to them quickly. Once you create a bookmark or favorite file you can access the list at any time and click on one of the site to go directly there.

Following path names

The URL is also what is called a path name. it describes the path to a particular file. By following the path name you may be able to loacte your position and find key pages within a Web site. For Example:

http://writing.colostate.edu/index.html

Notice that it ends in "index.html." this is a standard name for a homepage (this happens to be the homepage to the Writing Center Web site at CSU) so if you see it in the URL you know you're at a homepage or you can type it in at the end of the URL and you may get toa homepage.

Each backslash "/" denotes a new directory.Every directory that you chop off will lead you to a new directory homepage. For example if you chop off "/WritingCenter/index.html" you will end up at the department directory. If you then chop off "/Depts" you will end up with "http://www.colostate.edu" which is the homepage for CSU.

Using multiple browser windows

You should know about multiple browser windows for two reasons to avoid confusion when they open up on you and to use this tactic to your advantage.

A link may open up a new browser window and you might find that when you click your back button you don't go back to the site you were at. Just click on the the button on the toolbar at the bottom of your screen with the other browser and you will get back to where you were.

Sometimes you may find it helpful to use multiple browser windows, perhaps when you are filling out a form at one place and want to view information from another while you fill out the form or when you don't want to lose a site, but want to continue surfing.

Browser information

Discover detailed information about these browsers:

Note: Clicking on these links will open up a new browser window

Microsoft Internet Explorer

Netscape Communicator

Mozilla Firefox

Getting the Most out of the Site

To get the most out of any site you have to know what's there. Chances are that if you don't find what it is you're looking for or something interesting quickly you'll be on your way and looking somewhere else. The following list offers some tips for making the most out of a quick visit.

Effective scanning

There's just too much information on the Web to waste time reading unless you really need to. Learn to scan Web pages to locate the information you need. Look for key information in bulleted lists, menu bars, and other functional areas. Focus in on highlighting techniques that may lead you to key information.

Search

Many large Web sites will contain search functions. You are probably familiar with search engines such as Yahoo! or Excite. A search engine within a site does just what one of the larger search engines does only the search is limited to inside the site.

Search functions can be very helpful if you are looking for a specific piece of information within a large site.

Site Maps

Site maps are rather self explanatory, nevertheless a helpful feature of many Web sites that you may not be aware of. A site map is a graphical representation of the site. It will tell you where particular sections ar pages are found within the site.

Click on the "site map" button on the bottom of this page to view the site map of the Writing Center. The "previous" button on the top left hand corner of the site map will bring you back here.

Citation Information

Neal Bastek. (1994-[m]DateFormat(Now(), 'yyyy')[/m]). Reading the World Wide Web. The WAC Clearinghouse. Colorado State University. Available at https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/writing/guides-old/.

Copyright Information

Copyright © 1994-[m]DateFormat(Now(), 'yyyy')[/m] Colorado State University and/or this site's authors, developers, and contributors. Some material displayed on this site is used with permission.