Conducting Library Research

Contents

Understanding how to use the Internet and how to search the Web is critical to the research process; however, understanding how information is cataloged in your library and how to search and browse its stacks, special collections and journal rooms is equally important.

Libraries are the preeminent physical repositories for the results of human research and learning and continue to be the primary locations at which information on a multitude of subjects will be found.

Unlike many materials found on the Web, those found in a library are carefully vetted, or reviewed, for accuracy before being added to the collection. Once added, these items are categorized, cataloged and their locations mapped and recorded for easy retrieval.

To familiarize yourself with the facilities and services of your library, call its reference desk or pay a visit and speak with the librarian on duty. A guided tour may be available. A self-guided tour containing the same information should be available on their Web site as well.

Students at Colorado State University will find library hours, facility maps, electronic databases and catalogs, archives and collections, subject-librarian contact information and more directly accessible from the home page of the Morgan Library Website.

Library Staff

The Library Staff is one of the most overlooked resources in a library. The fact is they are constantly working with its catalogs, reference books and databases and know and them inside and out. As a rule they are generally aware of new additions to their collections before they are even entered into the catalog.

In larger libraries, you'll find librarians whose sole responsibility is to work in specialized departments like the social sciences reference desk or the government documents section. If you need help locating materials, need to learn how to use a particular database or just simply want to know how to use the catalog ask a librarian. They are there to help.

Reference Room

The Reference Room in most libraries contains an amazing array of resources. It's a good place to start a project, familiarize yourself with a topic or fill in and fine-tune your research. Details, definitions, dates, statistics and all sorts of other facts can be found in the reference room. The following are among the basics in any library:

- Dictionaries

- Encyclopedias

- Atlases and Gazetteers

- Statistical Sources

- Government Documents

- Handbooks and Companions

- Biographical Sources

- Periodical Indexes

- Bibliographies

- Pamphlets and Annual Reports

- Microfilm and Microfiche

Dictionaries

Library reference rooms include a wide variety of dictionaries, ranging from standard desktop issues like Merriam-Webster's to those designed specifically for single interest topics like foreign languages, abbreviations, slang or regional dialects.

You will also find academic and professional dictionaries like Black's Law Dictionary, Stedman's Medical Dictionary and the Oxford Dictionary of Natural History. The entries in these specialized volumes contain the terminology used in specific fields.

Unabridged dictionaries, in which you can find the most obscure words, learn their definitions and pronunciations are standard reference books in most libraries as well. The largest, in any language, is the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), now in its second edition.

The OED consists of twenty volumes and, in larger libraries, is often available in an electronic format. It not only defines each word but tells its etymology--or history--as well. It details the various meanings a word has held in the past and provides examples of its usage from the earliest appearance in the language to the present.

Encyclopedias

General encyclopedias, such as the New Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Encyclopedia Americana, are written for the non-specialist, someone who wants an overview of a topic, or are looking for a fairly general fact. These types of sources provide introductions to many subjects and may be especially valuable when first casting around for a research topic. Generally, they have an index volume and cross-references to help you in your search.

Once you've begun investigating more thoroughly, you may want to supplement your background reading by consulting more specialized encyclopedias that cover specific fields of study in greater depth. Often, they will include useful bibliographies of related sources. A sampling of titles includes:

- Dictionary of American History

- Dictionary of the Middle Ages

- Encyclopedia of Human Biology

- Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Encyclopedia of Psychology

- Encyclopedia of Religion

- Encyclopedia of Sociology

- Encyclopedia of World Art

- Encyclopedia of World Cultures

- McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology

- New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

- New Palgrave Dictionary of Money and Finance

- Encyclopedia of the American Constitution

Atlases and Gazetteers

Atlases and Gazetteers will come in handy when your research requirements contain a geographical component.

In addition to maps, many atlases include specialized information regarding the history, natural resources, ethnic groups as well as a wide variety of other topical subjects regarding specific countries and regions of the world.

Gazetteers, like the Columbia Lippincott Gazetteer of the World, contain alphabetical listings of place names and provide basic information such as location, recent population figures and the physical and cultural features that distinguish them.

The online U.S. Gazetteer, for instance, published by the U.S. Census Bureau, provides precise latitudes and longitudes of any place-name entered into its search field.

Statistical Sources

Statistical information is an important part of many research projects and most libraries house a large assortment of resources. Perhaps the most useful single compilation is the Statistical Abstract of the United States, a small volume containing hundreds of tables relating to populations, social issues, economics as well as a wide variety of other numerical data.

The Gallup Poll, a widely recognized barometer of public opinion, publishes statistical survey results in annual volumes as well as in monthly magazines and the federal government collects an extraordinary amount of statistical data, much of which is released through the U.S. Census Bureau.

When more detailed information than that found in the Statistical Abstract of the United States is required, ask your reference librarian for more options. The U.S. Census of Population and Housing or USA Counties may be available. The National Trade Data Bank and the National Economic Social and Environmental Data Bank, two popular sources of economic information put out by the Commerce Department, may be available as well.

Using Government Documents

Government documents are mostly thought of as congressional hearings, reports issued by state and federal agencies and presidential papers. But in fact, the government publishes information on practically every conceivable topic you can imagine. The following titles provide an idea of the wide variety of topics:

- Neurobiology of Seasonal Affective Disorder and Phototherapy

- Ozone Depletion, the Greenhouse Effect, and Climate Change

- Placement of School Children with Acquired Immune Deficiency

- Policy Implications of U.S. Involvement in Bosnia

- Remove Indians Westward (Committee on Indian Affairs, 1829)

- Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War (on the Battle of Bull Run, 1863)

- Small Business and the International Economy

- Strengthening Support and Recruitment of Women and Minorities to Positions in Education Administration

- Violence on Television

If you plan to use government documents in your research, don't be shy about asking a librarian for help. There are several indexes to government documents and most are electronically available. Among them:

- The Monthly Catalog of United States Government Documents is the most complete index to federal documents.

- The CIS Index specializes in congressional documents and includes a handy legislative history index.

- The American Statistical Index is a detailed index to statistical information found in government publications.

- The Congressional Record reports on the daily activity of the U.S Congress during each session.

Every year more and more electronic databases are created and released, making information, particularly statistical data, easier to access. For instance:

- Small-business statistics, the cost of pollution abatement programs, regional and state business conditions, and a wealth of other economic data will be found in The National Economic Social and Environmental Data Bank (NESE).

- Detailed population profile of your hometown, including age groups, income and education levels as well as ethnic origins can be found in the U.S. Census Report.

Handbooks and Companions

Between dictionaries and encyclopedias lies a species of reference book in which concise surveys of terms and topics relating to a specific subject will be found. They are referred to as handbooks or companions and their articles are generally longer than dictionary entries but more concise than those in a standard encyclopedia.

They can be a great help in clearing up questions that a research project might generate. What is fabianism? What is the novel Bleak House about? What films have been made about angels? Which animals practice mimicry as a defense mechanism?

Check with a reference librarian to see if there are specialized handbooks on your topic. The following list provides an idea of the variety you may find in your library:

- Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought

- Bloomsbury Guide to Women's Literature

- Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable

- Dictionary of Afro-American Slavery

- Dictionary of the Vietnam War

- Halliwell's Filmgoer's Companion

- Oxford Companion to Animal Behaviour

- Oxford Companion to English Literature

Biographical Sources

If you want to know about someone's life and work, libraries provide a rich array of sources. To help you locate them, tools such as Biography Index and the Biographical and Genealogical Master Index are generally available.

Directories that list the basic information regarding prominent people - degrees, work history, honors, address, etc. - include Who's Who in the United States, Who's Who in Politics and American Men and Women of Science. For more detailed biographical sketches, you may want to consult Contemporary Biography, Contemporary Authors, or Politics in America.

Several biographical sources contain substantial entries of people who have died: prominent Americans are covered in The Dictionary of American Biography, British figures in The Dictionary of National Biography. Prominent scientists from every nation and period of history will be found in The Dictionary of Scientific Biography.

Periodical Indexes

The most up-to-date information on a given topic is quite often published in periodicals-journals, magazines, newspapers or any other publication issued at regular intervals-rather than in books. A periodical index is a list of articles from a specific time period contained in a group of selected publications or that cover a group of related subjects. Organized alphabetically they may be searched by author, title and subject in the same manner as you would in a library catalog.

Often available in both print and electronic formats, periodical indexes include the source information-periodical title, volume, issue, and page numbers-needed to locate an article. Electronic indexes, often referred to as periodical databases, usually include more information on each article, such as abstracts or short summaries, than print-media indexes.

Bibliographies

Bibliographies are lists of sources on particular topics. Researchers compile and publish them after completing their work so that they will be available to other interested researchers. Besides books and periodicals, bibliographies reference a wide variety of other materials: films, manuscripts, letters, government documents and pamphlets that will lead you to sources that you may not otherwise have considered.

Authors record source information in several different places and formats. A full-length book may have a section labeled "Bibliography" at the back, or perhaps a section called "For Further Reading." If the author has quoted or referenced other works, they will be cited in the footnotes at the bottom of a page or a list of endnotes called "References" or "Works Cited" at the end of the book.

Book-length bibliographies on specific topics are also often available. Essential Shakespeare, for instance, is a book-length bibliography listing the best books and articles on the works of William Shakespeare. To locate such resources in an electronic database, such as a library catalog, simply add the word "bibliography" to a subject or keyword search.

If you're lucky, such a bibliography will include annotations that describe and evaluate each source.

Pamphlets and Annual Reports

Pamphlets and annual reports provide internal information on a wide variety of public and private institutions. When journalists need information, they get on the phone and make contacts, going directly to the source. You, too, can go directly to the source. Many organizations and companies gladly send out pamphlets, brochures and reports just for the asking.

As a reference, the Encyclopedia of Associations is a useful guide to organizations, categorized by name and subject. For government agencies, try the United States Government Manual. Ask your librarian where they are located.

Many libraries have already done the legwork for you, maintaining files of pamphlets organized by subject. A word of warning: take information from these types of sources with a grain of salt. Be discriminating: annual reports tend to paint a glowing picture of the companies they cover. Likewise, organizations advocating particular points of view will not hesitate to publish information in terms that are the most favorable to their overall objectives and goals.

Microfilm and Microfiche

Most libraries have microfilm and/or microfiche records. This technology puts a large amount of print material, such as whole newspapers and magazines, on durable strips of film that fit into small boxes or on a set of plastic sheets the size of index cards. Two weeks of the New York Times, for instance, can be put on a spool of microfilm designed to be fed through a manually operated machine designed so that readers may progress at a pace that suits them. In many cases full-sized pages can be selected, copied and printed.

In addition to newspapers and magazines, many libraries have other primary source material in microform format. For example, the American Culture Series reproduces books and pamphlets published between 1493 and 1875. Colonial-era religious tracts or nineteenth-century abolitionist pamphlets can be examined without having to travel to a museum or view a rare books collection. Likewise, the American Women's Diaries collection provides rare firsthand glimpse of the past through reproductions of diaries kept by women living in New England and the South, as well as pioneer women traveling west.

Library Catalog

The Library Catalog provides bibliographic information about the books, periodicals, videos, databases and other collections owned by a library. In the past, these records were kept on 3 X 5 cards in the wooden drawers of a card catalog. Today card catalogs are pretty rare: most libraries have converted to electronic databases searchable via the Internet.

Regardless of the form of access, the function is the same: to describe where the materials contained in a library collection are located and to make that information accessible through either an author, title or subject search.

Each item in a library catalog is identified by a call number that explains its physical location. These numbers are carefully chosen so that books and materials on the same subject will end up next to each other on the shelf. College and university libraries generally use the alpha/numeric Library of Congress classification system while local community libraries generally use the older and more familiar numeric Dewey Decimal system.

Libraries that predate the Library of Congress system will often use both. In any case, devote some research time just to browsing the stacks. You will find many great resources sitting on the shelf right next to the ones you found while searching the catalog. Think of it as an informational treasure hunt: you will be surprised at the resources available that you may otherwise never have discovered.

Certain subjects are not clearly included in either system-some fields, like computer science, mass communications, and environmental studies are newer than the classification systems themselves and so will be found sandwiched into other, related areas. Again, ask your librarian for help when you are unsure how materials are categorized or where to look for them.

Searching the Online Library Catalog

Searching the Online Library Catalog can be done either by author, title, subject or keyword. The first two are fairly straightforward. An author's name, or the title of a book, journal, magazine, newspaper or multi-media item, is entered into the search field and the results are displayed in a new browser window. Subject searches are a bit more complicated and are often more successful when done in combination with a keyword search.

Author Search

Author searches are used to locate works written by an individual, a group of individuals or a larger entity like a corporation, organization or government agency. Most search fields require the last name of an individual be entered first. First names or initials, included after a comma, will narrow the search.

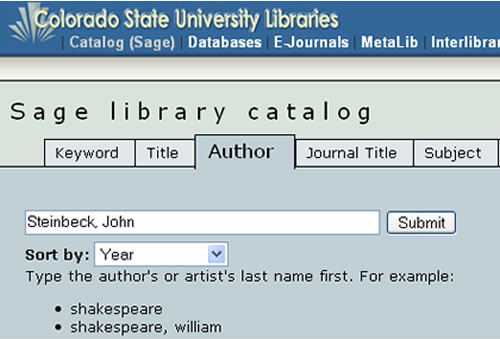

Steps of an Author Search Using CSU's SAGE Catalog

Step One

The screen-shot below illustrates the first step in a SAGE author search for works by John Steinbeck. Feel free to open the SAGE catalog in a new browser window and become the researcher yourself. Select the "Author" tab and then follow the discussion below.

As you can see, the researcher has selected the Author tab and entered the author's name into the search field. Notice the results are to be sorted by year, one of the choices provided on the drop-down menu.

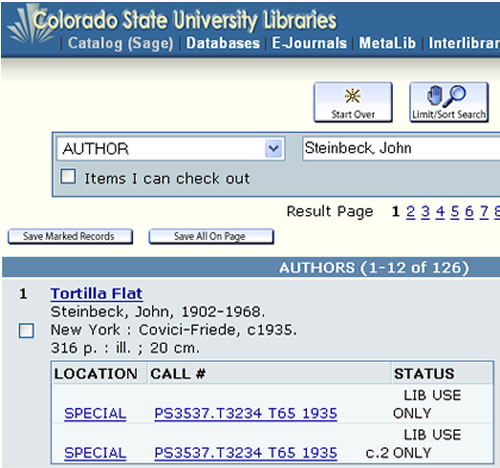

Step Two

This screen-shot illustrates the results page returned after submitting the request.

Notice the results include 126 records of which the first 12 are displayed. Each record will also display information about the author, the book, the publisher and, most importantly, its location, call # and status. As you can see, there are a number of electronic links available.

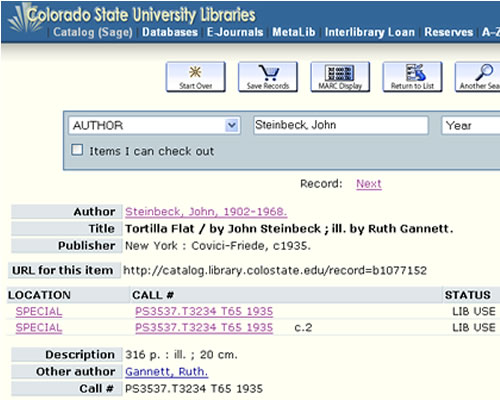

Step Three

The final screen-shot illustrates the expanded information that comes from clicking on the underlined title.

Title Search

Title searches are used to locate specific works written by an individual, a group of individuals or a larger entity like a corporation, organization or government agency. Most search fields will accept a partial title when you are unsure of its exact wording.

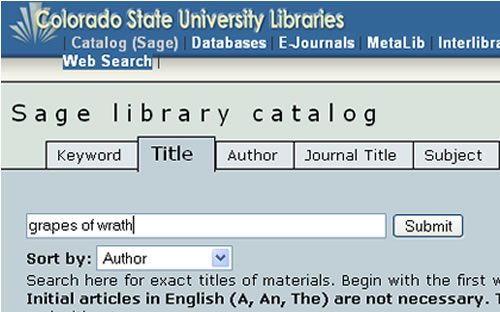

Steps of a Title Search Using CSU's SAGE Catalog

Step One

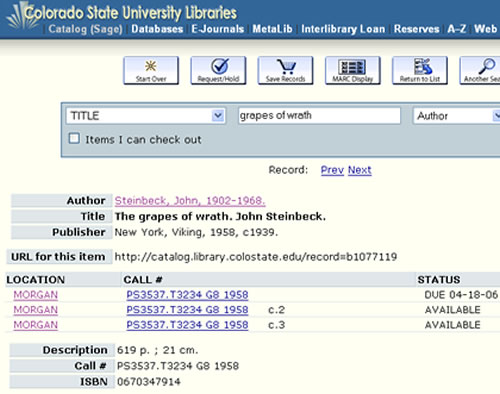

The screen-shot below illustrates the first step in a SAGE title search for John Steinbeck's American classic, The Grapes of Wrath. Feel free to open the SAGE catalog in a new browser window and become the researcher yourself. Select the "Title" tab and then follow the discussion below.

As you can see, the researcher has selected the Title tab and entered the name of the book into the search field. Notice also that the results are to be sorted by Author, one of the choices provided on the drop-down menu and that the search field is not case sensitive.

Step Two

The next screen-shot illustrates the results page returned after submitting the request.

Notice the researcher had to scroll down the results page looking for the first record of a book titled The Grapes of Wrath written by John Steinbeck. It shows up ninth on the list. That's because there are 34 records displayed, indicating that other books have been written about this title and its author.

As you can see, there are a number of electronic links available to you. Each record displays information about the author, the book, the publisher and, most importantly, its location, call # and status.

Step Three

The final screen-shot illustrates the expanded information that comes from clicking on the underlined title.

Subject Search

Subject searches are more complicated than author and title searches. To be effective you need to create a list of likely headings under which your topic might be cataloged. An extensive list of standard terms used by most libraries can be found online in the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH).

Steps of a Subject Search Using CSU's SAGE Catalog

Step One

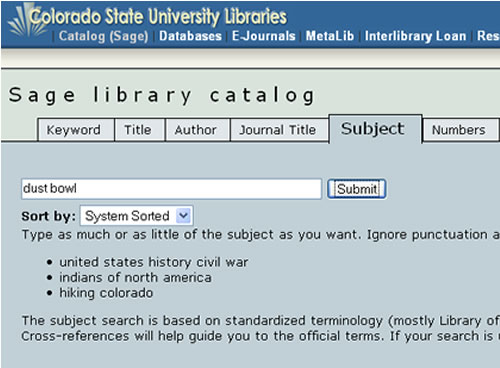

The screen-shot below illustrates the first step in a SAGE subject search for source material about the "Dust Bowl", the 1930's natural disaster in which John Steinbeck set his American classic, The Grapes of Wrath. Feel free to open the SAGE catalog in a new browser window and become the researcher yourself. Select the "Subject" tab and then follow the discussion below.

As you can see, the researcher has selected the Subject tab and entered a subject heading into the search field. Notice also the results are to be sorted by the system-sorted option, the default choice provided on the drop-down menu.

Step Two

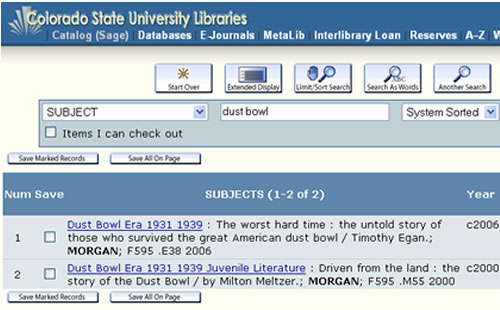

This screen-shot illustrates the results page returned after submitting the request.

This search only produced two results. Notice that one is for children. Each record displays information about the author, the book, the publisher and, most importantly, its location, call # and status.

Step Three

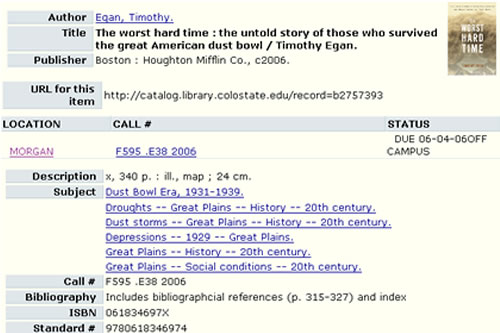

The final screen-shot illustrates the expanded information that comes from clicking on the underlined title of the first record.

In this case, the researcher knows the dust bowl has been written about extensively and that there is most likely more source material than these results indicate. Further subject searching can be conducted with a Keyword search.

Keyword Search

A keyword search is more flexible than a subject search. But to be effective you first need a list of likely keywords that can be entered individually or in various combinations into the search field. Start with subject headings. An extensive list of standard terms used by most libraries can be found online in the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH).

Steps of a Keyword Search Using CSU's SAGE Catalog

Step One

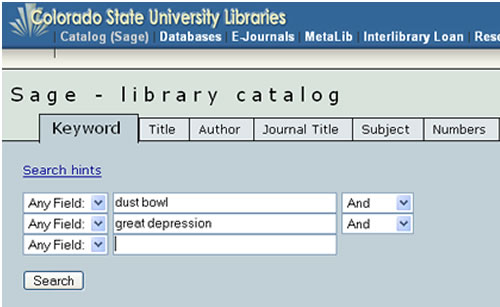

The screen-shot below illustrates the first step in a keyword search for source material about the "Dust Bowl", the 1930's natural disaster in which John Steinbeck set the great American classic, The Grapes of Wrath.

Feel free to open the SAGE catalog in a new browser window and become the researcher yourself. Just follow the discussion below.

As you can see, the researcher has selected the "Keyword" tab and entered a subject heading into the first two search fields. Notice that the results are to be tied together by the Boolian search term AND, which instructs the search engine to return all records having both sets of words.

Step Two

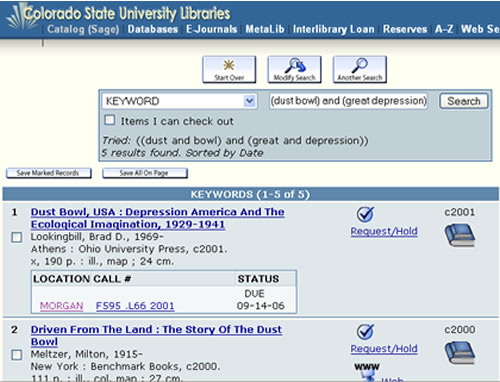

This screen-shot illustrates the results page that returned after submitting the request.

As you can see, five records have been found. Not great, but it's better than the two records turned up in the previous subject search tutorial. A further search is in order.

Step Three

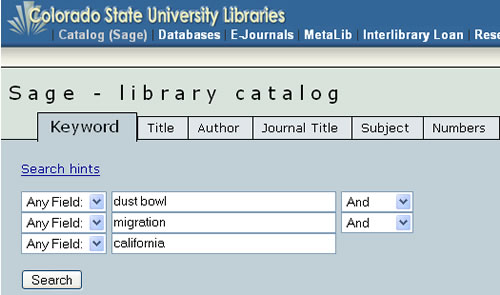

This screen-shot illustrates a return to the initial keyword search page for another try.

As you can see, the keywords migration and California were added to the search fields and great depression was left out.

Step Four

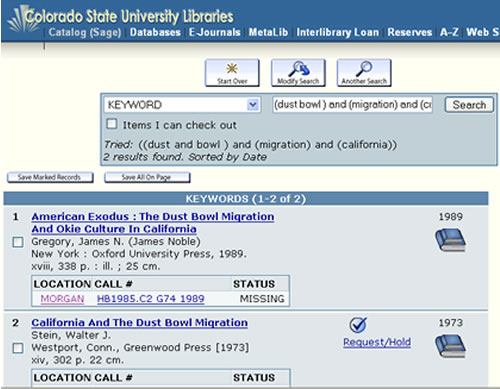

The final screen-shot illustrates a new results page.

The researcher was able to identify two new sources and, in this case, neither one was among those turned up in the first search. There are now seven useful titles related to the 1930's dust bowl that can be added to the working bibliography.

Be aware that duplication is more the rule than the exception and be prepared for its likelihood as you continue combining keywords in your search.

Your skills will naturally improve as you familiarize yourself with your library's online catalog. Be aware that this type of searching will also generate a lot of irrelevant titles along with the useful ones, especially if the terms entered are fairly common or generic. Learn to be specific.

Databases and Electronic Indexes

Databases and Electronic Indexes are collections of information stored on CD-ROM's, the Internet or commercial Web sites generally accessible only through a subscription. The information they contain is organized into electronic fields, records and files so that a computer program-or database management system-can easily find requested items. Their organization is much like that of a filing cabinet:

- An electronic field is one piece of information: one electronically digitized journal article.

- An electronic record is a collection of fields: one folder containing ten related journal articles.

- An electronic file is a collection of records: one drawer containing 100 folders, each containing ten related journal articles.

- An electronic database management system is the whole filing cabinet: four drawers, each containing 100 folders, each of which contain ten related journal articles.

Some databases provide information that is primarily numeric, such as government census data. Other databases, like the Modern Language Association's MLA Online, contain primarily textual information. Hypertext databases, on the other hand, will contain a wide variety of electronically digitized information ranging from word documents and photographic images to audio and video feeds.

When a database presents information about other publications, such as books, periodicals, or government documents, it is called an electronic index. They are the electronic equivalent of print-format indexes-like the Periodical Index-found in the library Reference Room.

You'll find three broad categories of databases and electronic indexes in most college or university libraries. These range from general indexes, such as the Reader's Guide to Periodic Literature, to specialized indexes and government databases.

There are a wide range of electronic databases on the Internet. Some of them are free. Most, however, are available only by subscription. All university libraries pay licensing fees to a wide variety of selected databases in order to provide students, faculty and staff with the necessary access.

These licensing agreements often only allow access through library computers or those connected to the campus network. Contact your library to determine which databases you can access via the Internet.

Here are two of the most useful databases available without a subscription:

- ERIC: a Database containing more than 1.2 million abstracts of documents and articles in the field of education.

- FedWorld: a Web site providing access to thousands of U.S. Government Web sites and more than a 1/2 million U.S. Government documents, databases and other information products.

General Indexes

An index is a guide to the material published within other works, mostly periodicals. In a periodical index, you'll find every article for the periodicals and the period covered, typically listed by author, title, and subject. It will also include the source information, such as issue and page numbers.

Several common indexes will help if you're looking for general interest magazine or newspaper articles. The Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature is a good example and is available in print, on CD-ROM, and online. The printed version is a good choice, however, if you are doing any historical research. Begun in 1900, its older volumes are useful in locating popular press coverage of events happening at any time in the twentieth century-for example, articles about the bombing of Pearl Harbor published in the days after it happened.

Likewise, the New York Times index will help you track down that newspaper's coverage of events back to 1851. Another popular index is InfoTrac, a computerized resource that emphasizes materials written for a fairly general audience (though one version, the Expanded Academic Index, includes scholarly journals).

NewsBank, is an index to newspapers that draws on more than 500 local U.S. newspapers. Updated monthly, it is available both in print and on CD-ROM. Your library may also have an index to a local newspaper as well, which can help you track issues in your area. Some computerized indexes include downloadable and printable abstracts and full-text articles.

The Humanities Index, the Social Sciences Index, the General Science Index, the Business Periodicals Index, or PAIS International, an index focusing on public affairs, are aimed at more specialized audiences and provide more analysis than those found in popular magazines. The computerized Expanded Academic Index provides the same kind of coverage as the first three of these indexes. These tools index the most important scholarly journals in their fields, but they don't include obscure or highly specialized publications. The articles found in these indexes will be fairly long, include footnotes, and be based on and give detailed research information. These are the kinds of indexes you'll want to use for detailed research on social issues, literary criticism or science and medicine.

Specialized Indexes

Specialized indexes list books, articles, dissertations, and other specialized materials relevant to their specific disciplines. Many of the items they list are obscure and available only in the largest libraries.

These indexes are great resources if you are working on an in-depth project and need to track down hard-to-find source material. The following specialized tools-and dozens more-are available both in paper and electronic form.

- America: History and Life

- Biological Abstracts (Biosis)

- Index Medicus (Medline)

- MLA International Bibliography

- Psychological Abstracts (PsycINFO)

A reference or special-sections librarian can help you locate and use the specialized indexes housed in your library as well as those of other research libraries accessible through the interlibrary loan system.

Government Databases

The federal government is the most prolific publisher in the world and, in an effort to make information accessible to all citizens; libraries in many locations serve as depositories for government publications. If your college library isn't a depository, there may be one nearby. Large libraries often have collections of local and international documents as well.

If you plan to use government documents in your research, don't be shy about asking a librarian for help. There are several indexes to government documents and most are electronically available. Among them:

- The Monthly Catalog of United States Government Documents is the most complete index to federal documents.

- The CIS Index specializes in congressional documents and includes a handy legislative history index.

- The American Statistical Index is a detailed index to statistical information found in government publications.

- The Congressional Record reports on the daily activity of the U.S Congress during each session.

Every year more and more electronic databases are created and released, making information, particularly statistical data, easier to access. For instance:

- Small-business statistics, the cost of pollution abatement programs, regional and state business conditions, and a wealth of other economic data will be found in The National Economic Social and Environmental Data Bank (NESE).

- Detailed population profile of your hometown, including age groups, income and education levels as well as ethnic origins can be found in the U.S. Census Report.

Every year more and more databases like these are being released. If you plan to use government documents in your research, don't be shy about asking a librarian for help. The documents can be difficult to locate on the shelves, and since new computerized sources are coming out all the time, it's wise to get an expert on your side.

Online Document Dollections

Online document collections contain electronic versions of printed texts, often classic texts on which the copyright has expired. Leading collections include the following:

- Project Gutenberg is an online catalog of over 18,000 free books, all of which the copyright has expired, that are downloadable as E-books.

- The New Bartleby is a Website providing teachers and students free access to online reference material on literature and poetry.

- Internet Archive is a Web site archive of free accessible electronic political documents, periodicals, discussions and e-zines.

As with library collections, online document collections are growing in number and scope. In addition to the public sites mentioned above, your library may subscribe to any number of commercial collections, such as the Electric Library. To learn which collections your library subscribes to, consult a reference or subject area librarian.

Interlibrary Loans

Interlibrary loans facilitate the borrowing of materials from other libraries without actually having to go to them. There are a number of reasons for using this service:

1) Your library may not have the item you are wanting

or

2) Someone else may have already borrowed the item from the library you most often use.

The first is a common occurrence: Not all the contents of a library collection are the same as the next. The second, equally common, occurs when many students attending the same college or university are working on a similar assignment, especially during the same semester: a sound argument for not procrastinating, or waiting till the last minute, to begin your research project.

Most colleges and universities allow you to make an interlibrary loan request from your own personal computer or from any of the computers located in the library itself or in computer labs located elsewhere on campus. The online request form should be self-explanatory; however, in the event it is not, any librarian will be able to assist you in learning the procedure.

Citation Information

Mike Palmquist and Peter Connor. (1994-[m]DateFormat(Now(), 'yyyy')[/m]). Conducting Library Research. The WAC Clearinghouse. Colorado State University. Available at https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/writing/guides-old/.

Copyright Information

Copyright © 1994-[m]DateFormat(Now(), 'yyyy')[/m] Colorado State University and/or this site's authors, developers, and contributors. Some material displayed on this site is used with permission.