CHAPTER FOUR

Ongoing Writing Tutor Education:

Models and Practices

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Julia Bleakney

Elon University

When writing center professionals (WCPs) plan tutor education, they are challenged to balance introducing theories, creating opportunities for practice, and scaffolding ongoing reflection and evaluation of tutors' work. Tutor education typically starts with theory, as a way to prepare tutors for informed practice. Once tutors move to the everyday of writing center tutoring, ideally they will use the theory they've learned to ground their practice and guide them through unfamiliar situations. Ongoing education offers tutors the opportunity to revise or "re-see" their practice, just as we teach tutors to invite writers to revise their writing, to see it in a new way. Without ongoing education, as Mark Hall suggests in "Problems of Practice," tutors "may feel done [after an initial course or other type of initial education], certified to be effective writing tutors. With time, they may slip into familiar and unquestioned routines. Staff meetings may become narrowly focused on the practical, neglecting the writing center as a site of research and knowledge-making." For these reasons, for Hall, "courses are just the beginning of tutor education" (1).

Without a doubt, WCPs appreciate the value of ongoing development for their tutors. Yet Hall's piece is one of the few publications that explicitly considers what this ongoing education could look like in relation to initial education opportunities, in a course or otherwise. When WCPs wish to develop a new ongoing education program or when they seek to reinvigorate an existing one, they have a few research pathways, as mapped out here:

- Review case studies of individual writing centers' education models; e.g. Nakamura, Dvorak, Hughes and Tedrowe;

- Introduce tutors to particular theories; e.g. Denny, Hill or to specific issues that tutors encounter, such as working with multilingual learners or writing in different disciplines;

- Seek organization and collegial support via the WCenter listserv or affiliate or international writing center conferences.

All of these options are valuable, as WCPs can seek advice and draw on different frameworks or practices that have been tested at other writing centers and tailor them to their own institutional contexts. Yet, surely some WCPs feel that they unnecessarily reinvent the wheel as they develop a new education model that might already be in place at another, similar type of institution, or as they implement and then revise a model because they did not anticipate all the pitfalls. Certainly this was my experience when I set out to revise the ongoing education at my new institution; I sought, unsuccessfully, to find published studies of education models that scaffolded tutors' learning and development from an initial course into ongoing education, though I had felt sure that such articulated models existed. I was aware that the writing center field already has a great deal of "field-driven expertise" (to use a term from Russell Carpenter et al. in this collection) about what works and doesn't work in ongoing tutor education. The purpose of this chapter, then, is to showcase that knowledge: to review the different types of ongoing writing center tutor education models, based on the results of a national survey of writing center professionals and follow-up interviews; to identify what WCPs believe are smart practices for ongoing tutor education; and to provide models and resources for writing centers that wish to develop or revise their own tutor education models.1

Study Design and Analysis

In April 2017, I solicited survey participants from subscribers to the WCenter listserv and from WCPs who had taken the 2014-2015 Writinheading1g Centers Research Project (WCRP) survey; I used the same questions related to center demographics and institution type as the WCRP, with permission. To the survey, I added questions asking WCPs to identify how they educate their tutors when they are first recruited or hired as well as after an initial course or orientation, and how they assess their education offerings. I collected and coded the responses in Qualtrics. Of 164 respondents, 154 completed all questions in the survey.2 Just over 92% (see Table 1) of respondents offer some kind of ongoing education after an initial course or orientation. Some questions gave respondents a menu of options to choose from, some of which included text-box space for "other" responses; other questions were open-ended. I manually coded the written-in responses to the "other" options and the open-ended responses.3 Centers with ongoing education may be overrepresented because, even though the call for participants invited everyone to respond, including those without any ongoing education, it is possible that respondents with developed ongoing education models were more motivated to participate.

After analyzing the survey responses, I identified possible candidates to invite for interview. I first organized the willing respondents by Carnegie Classification (Two-Year College, Four-Year Liberal Arts, Regional/Comprehensive, and Research 1) and by public and private institution categories, with the goal of selecting interview participants from each category. When there were more participants in a classification category than I could interview, I identified potential participants who represented different education models (for instance, one whose writing center offered an initial course and another whose did not) and assessment plans. In total, I invited via email twelve survey respondents to be interviewed, and I interviewed nine. I conducted the interviews over a period of a few weeks; each interview lasted between 30-45 minutes and was recorded using tools such as Zoom and WebEx. I completed transcriptions using Trint, which I then manually corrected. I analyzed interview responses descriptively and holistically (Saldaña), coding responses into broad categories (presented in the interview section below) and selecting examples to present aspects of different centers' tutor education models.

The State of the Field: Results from a National Survey

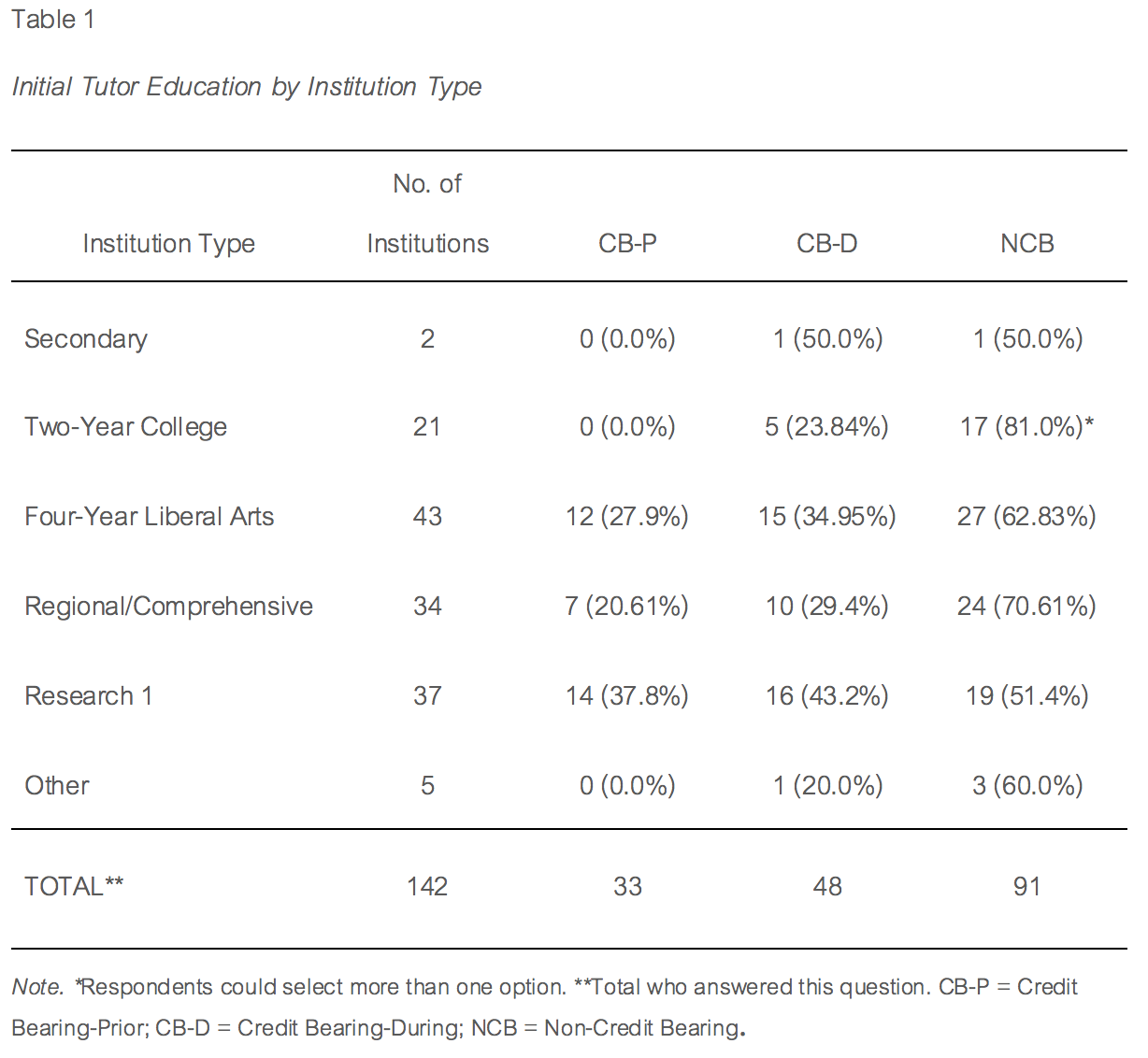

The survey invited respondents to select from a menu of initial education offerings, as summarized:

- CB-P or Credit Bearing-Prior: a credit-bearing course prior to students beginning their work as tutors in the center

- CB-D or Credit Bearing-During: a credit-bearing course that students take while also working as tutors

- NCB or Non-Credit Bearing: non-course based education opportunity prior to students working as tutors.

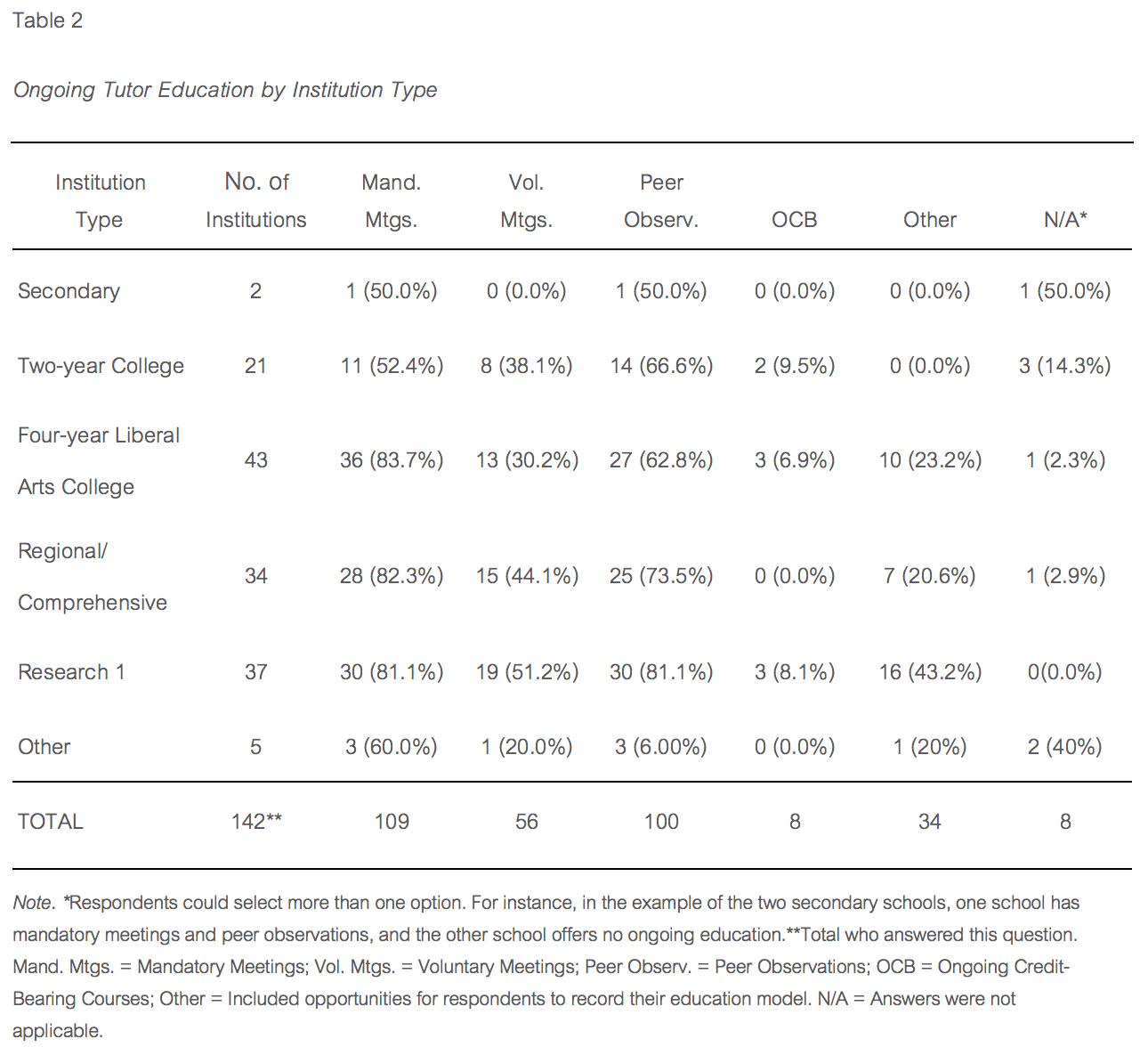

The survey also asked respondents whether they ran mandatory or non-mandatory (voluntary) meetings or peer observations and whether they offered other forms of ongoing credit-bearing education (OCB), such as through CRLA (Tutor Training Program Certification through the College Reading and Learning Association. Finally, the survey asked participants to indicate if and how they assess their ongoing education. Because undergraduate and graduate tutors have different educational needs (see Craig Medvecky in this collection), I asked respondents to refer specifically to the education they offer for their undergraduate tutors. For a study of graduate student education offerings, see Kat Bell's chapter in this collection.

Institution Type

I wanted to contextualize the ongoing education offered in terms of initial education, as presented in Table 1. The responses in this Table show there are fewer credit-bearing courses, CB-P or CB-D (33 + 48 = 81), than non course-based (NCB) initial education, such as a weekend orientation (91). The responses also show that Research 1 institutions are more likely to offer credit-bearing course options (38% offer CB-P and 43% offer CB-D), than an NCB opportunity (51%); 4-year liberal arts colleges are split evenly between offering any credit bearing course and NCB (63% of respondents offer each). Regional comprehensives are more likely to offer NCB (71%) than a course (21% offer CB-P and 29% offer CB-D). This trend is more true of 2-year postsecondary colleges, none of which offer CB-P, and which are more likely to offer an NCB orientation (81%) than CB-D (5 24%).

In terms of ongoing education, Table 2 shows that the most common types are mandatory meetings and peer observations, which I discuss in more detail below. Thirty-four respondents indicated that they offer some "other" type of education; the most common in this category is an observation by a director or graduate assistant (10 or 23.2% of the "other"). When peer observations from this category are added to the total in the Peer Observations column, the number of writing centers using observations increases to 110. Additional education offerings in the "Other" column include mentoring (4), independent professional development or group projects (3), practicum (3), reflective writing (3), attending or presenting at conferences (2), recording and transcribing tutoring sessions (2), research (2), Tutor Training Program Certification through the College Reading and Learning Association (CRLA) (2), and other one-off types (3).

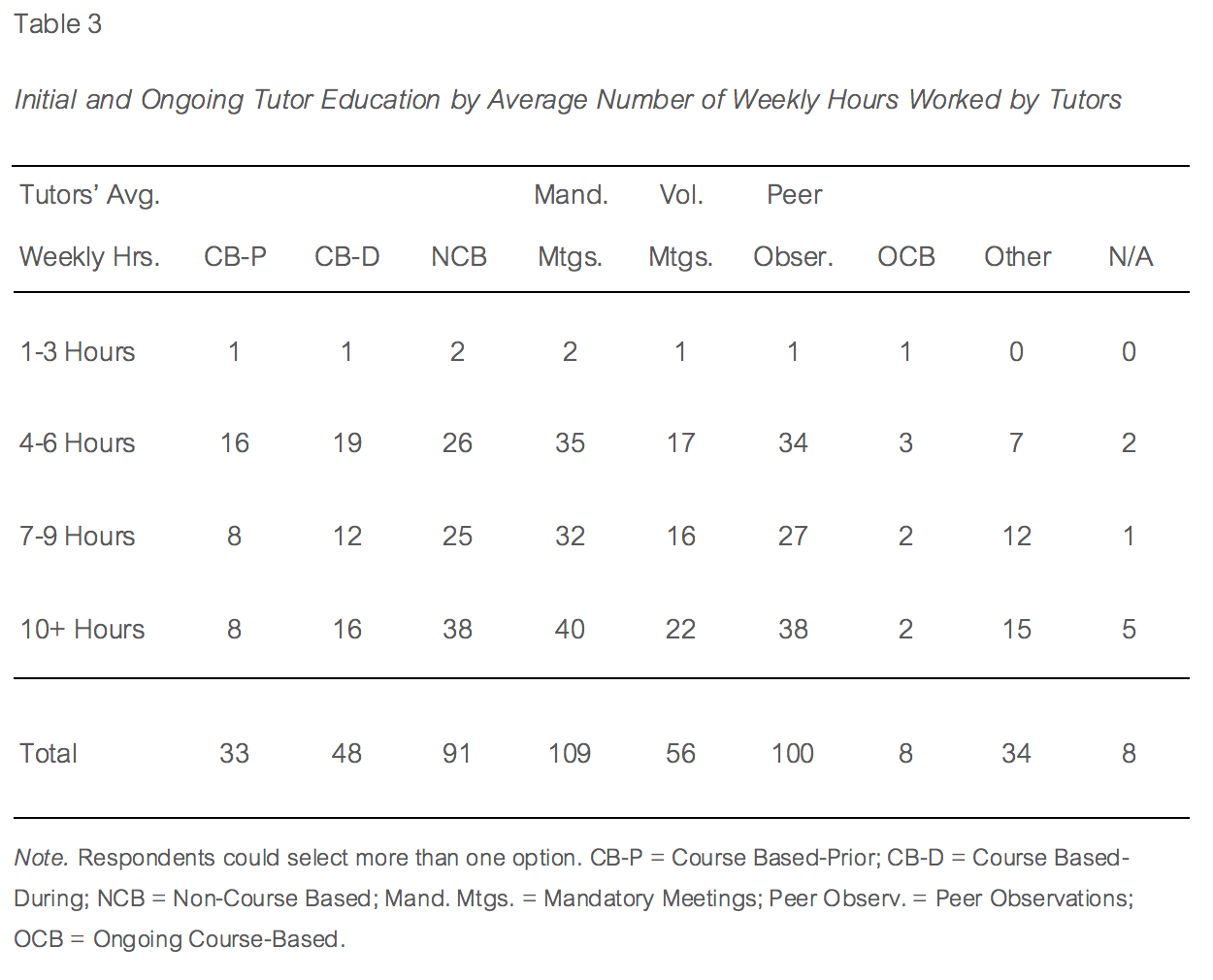

Tutor Hours Worked

In addition to examining education offerings by institution type, I hypothesized that the type of education offered might be impacted by the number of hours that tutors work in the center. Comparing centers where tutors work between 4-6 hours with those whose tutors work 10 or more hours, Table 3 shows that in centers where tutors work between 4-6 hours, 43.8% (or 35 of 81 of the total number of respondents who provide CB-P or CB-D education) offer CB-P or CB-D, and 28.5% (26 of 91) offer NCB. For responses from centers where tutors work 10+ hours, fewer centers, 26.9% (24 of 81), offer a course, and more, 41.7% (38 of 91), offer NCB. In other words, it appears that centers that employ tutors for 10+ hours are less likely to offer a course and more likely to have other initial education offerings that are not course-based. Thus, I surmise that tutors may work more hours because they must attend mandatory meetings, especially when a course is not available.

Meetings—Prevalence, Frequency, Content, and Format

Tutor meetings in their various forms are the most common type of ongoing tutor education (mandatory and voluntary meetings showed up 165 times in the responses), more so for responses (69) from centers without a course than with (30). In responses from centers where tutors work 4-6 hours, as seen in Table 3, 52 run meetings; in responses from centers where tutors work 10+ hours, 62 run meetings. This indicates a slight increase in the prevalence of meetings in centers where tutors work more hours.

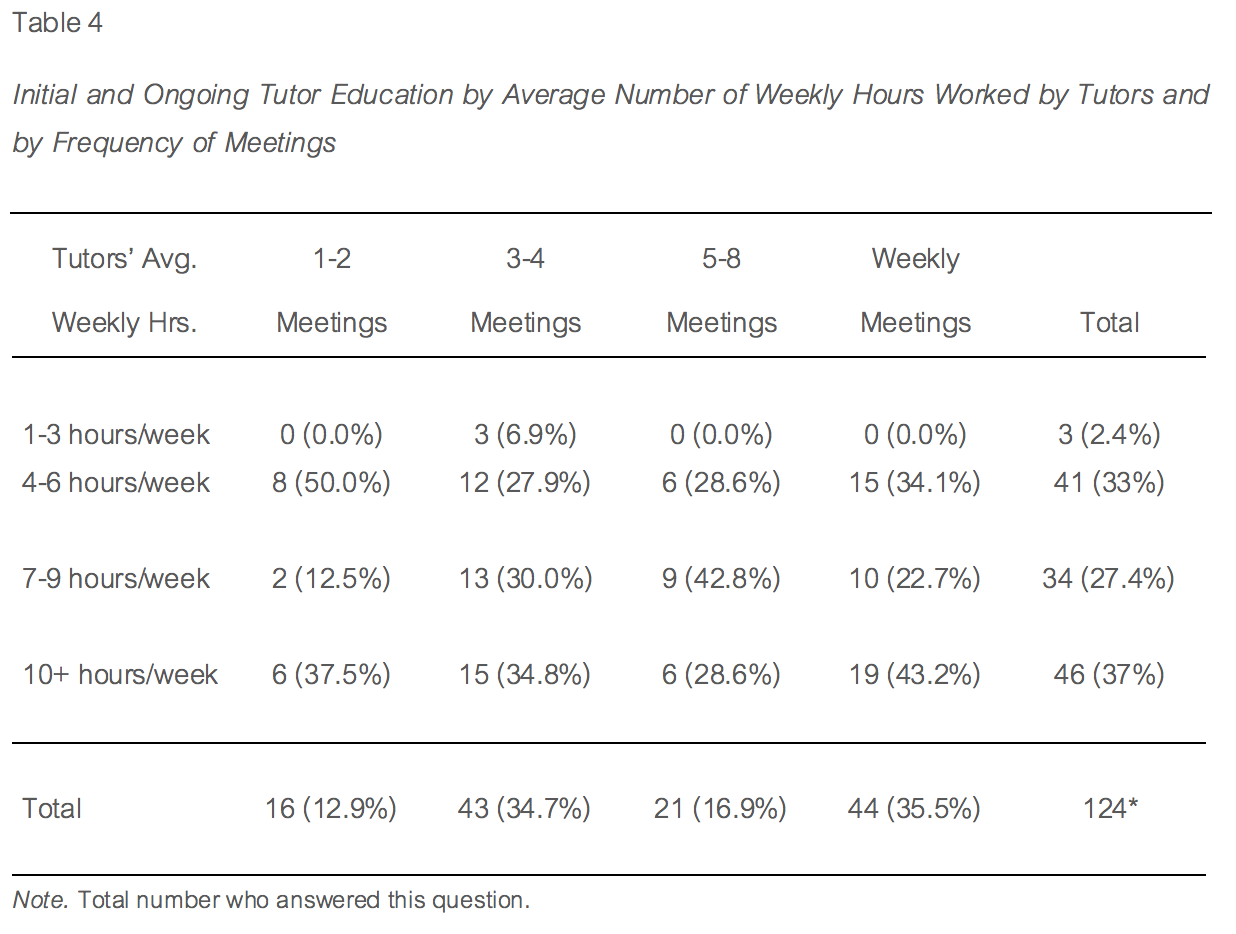

From the survey responses, we know that meetings are prevalent at most writing centers; Table 4 shows a relationship between the frequency of these meetings and the average number of hours worked by tutors. The highest number of centers with weekly meetings (19 or 43.2%) has tutors working 10+ hours per week, but this number is not significantly higher than the weekly meetings (15 or 34.8%) in centers whose tutors work 4-6 hours per week. In addition, more centers with tutors who work 10+ hours per week have once a month meetings (15 or 34.8%) than centers whose tutors work 4-6 hours per week (12 or 27.9%), but again the difference is small. There was a higher response rate (46 or 37%) from centers whose tutors work 10+ hours a week, which might skew the numbers; however, it appears that in centers where tutors work less than 10 hours a week, similar amounts of ongoing education opportunities are offered. An important take-away from these data, therefore, is that a center whose tutors work fewer hours may be holding similar amounts of meetings for and with their tutors.

I asked respondents an open-ended question about what they do during their tutor meetings; 130 respondents (79% of n=164 total) provided details about the meeting content and format. They described activities such as practicing consulting, reviewing student writing, and discussing consulting challenges or readings. (The complete list of activities is available here.) Just 27 (or 20.7%) indicated that they used a lesson plan. Over half of the 130 responses described sessions lasting somewhere between 60-120 minutes, starting with check-ins and/or announcements, followed by a presentation or an application activity, and then a wrap-up. Some centers vary the order of these elements. Sessions are commonly led by a director (80 or 61.5%), with a presentation or activity led by tutors (44 or 33.8%) or by a guest speaker (32 or 24.6%).

Variations on traditional tutor meetings included shorter (30-40 minutes) or longer (3-4 hours) meetings, meetings held in the context of a one-credit practicum course, or training through online course management systems. One variation rotates different types of workshops each week. In this example, the education model cycles through a tutor-run session called Coffee & Commenting that focuses on practicing delivering feedback, a workshop led by a professional tutor, and other training proposed and designed by tutors. Another weekly rotation model offers "staff-led meetings on pedagogy or a specific training topic [and then] Reading Group, led by junior staff members who select readings and lead the discussion." These open-ended responses show writing centers balancing common types of activities in meetings with variation to suit specific contexts and cultures.

Peer Observations

Peer observations are the second most common type of tutor education, with 100 respondents indicating they incorporate this type of experience into their model (see Table 3). Peer observations are more common for centers with NCB (65%) than for centers with CB-P (24%) or CB-D (38%). (To calculate this, I cross-referenced responses in Qualtrics.) Yet it would seem that the number of weekly hours worked by tutors has little impact whether on peer observations are offered. As Table 3 shows, in centers where tutors work 4-6 hours, 34 (34%) use observations, and in centers where tutors work 10+ hours, 38 (38%) use observations (see Table 3). From this result, we can see that centers where tutors work fewer hours are still able to build observations into their ongoing education.

Overall, the majority of writing centers (92.3%) offer some form of ongoing education in addition to an initial course or orientation; most of that ongoing education is via tutor meetings and peer observations. The survey also found, in general, that centers that employ tutors for fewer than 10 hours per week provide a similar amount of meetings and peer observations as centers whose tutors work more than ten hours per week.

Assessing Ongoing Education

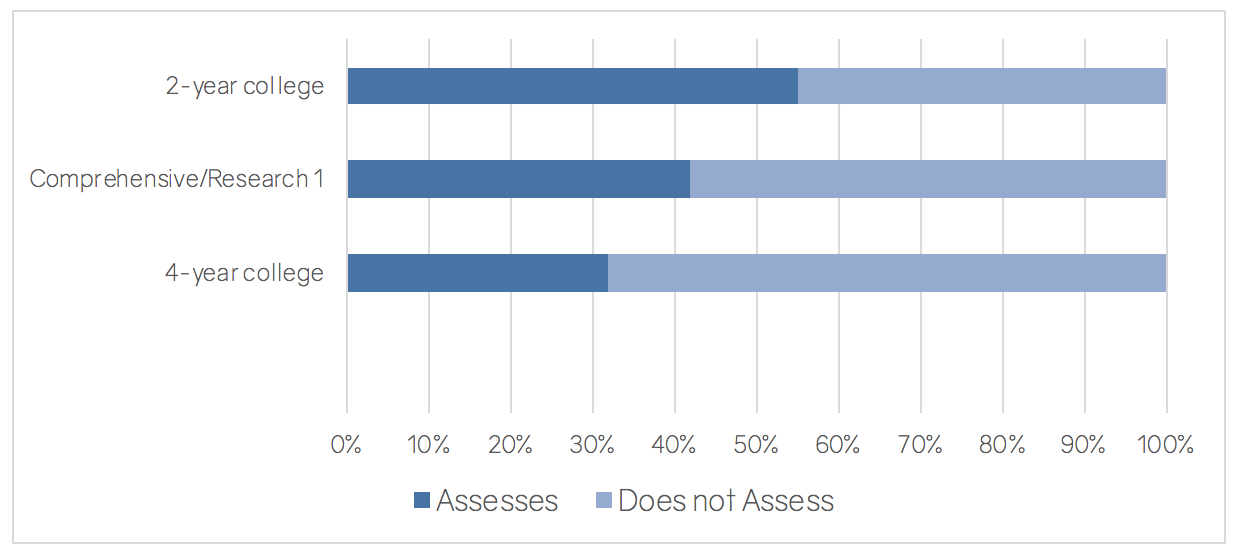

In this study, I wanted to understand not only how writing centers build ongoing models of tutor education but also if and how they evaluated their education offerings. Sixty-four respondents (39%) indicated that they assess their tutor education; an additional 32 (19.5%) said they don't currently, but plan to; and the rest (37.8%) said they do not assess their ongoing education or left this question blank. In terms of assessment by institution type, Figure 1 shows assessment across institution type where data is available.

|

| Figure 1. Rates of assessment by institution type. |

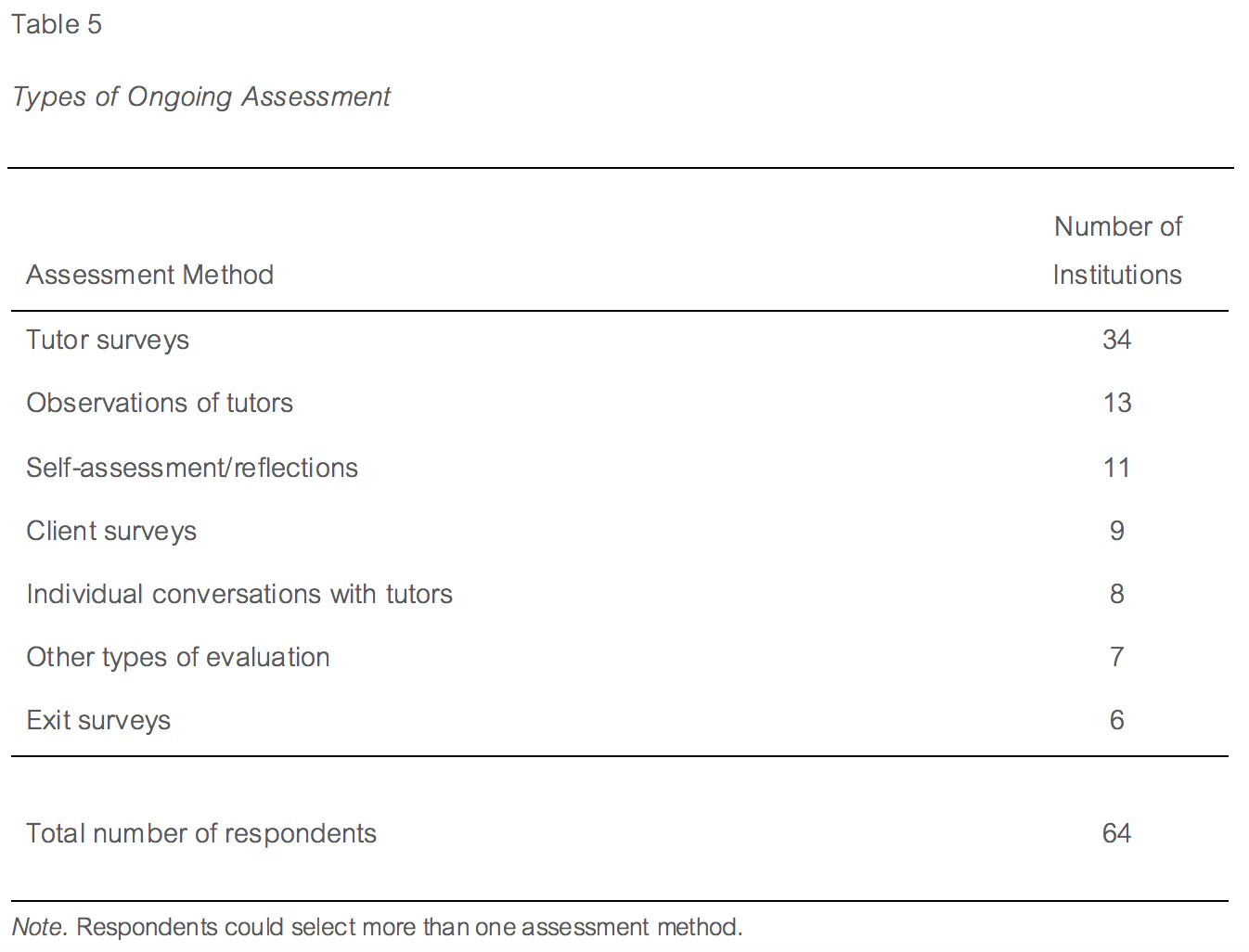

Those who do some form of assessment describe using a variety of methods, as presented in Table 5. Because respondents could select "all that apply," the results show that some writing centers are using multiple assessment measures. For instance, one center assesses in four ways, with post-training survey forms, once-a-semester tutor observations, self- and supervisor-evaluations, and student satisfaction and faculty surveys. Another described the relationship they see between the different components of assessment:

The tutors are CRLA certified, which means that they have to be evaluated regularly, both by students (I try to get tutor evals read and compiled weekly so I can discuss results with tutors weekly) and by me (twice a semester we have an overall evaluation). I should be seeing improvement in my tutors as they progress through their training. If that's not happening, then I look...at the quality of the tutor and reassess the training—what do I need to better emphasize?

Other writing centers run only one type of assessment, the most typical being tutor surveys administered after meetings or training sessions. Some writing centers count peer observation as assessment, highlighting its importance as a tool for tutor improvement. With the exception of tutor surveys, other assessment types—such as client and exit surveys or self-assessment—seem to evaluate the tutoring program more generally rather than the effectiveness of the ongoing education opportunities specifically. Concerned that perhaps the survey did not accurately capture the assessment of ongoing education that is occurring, I made sure to ask about it in the interviews. Given that some writing centers from this study do not survey their tutors after meetings or training sessions, it seems likely that the number of writing centers currently assessing their ongoing education is actually less than 39%.

Other writing centers run only one type of assessment, the most typical being tutor surveys administered after meetings or training sessions. Some writing centers count peer observation as assessment, highlighting its importance as a tool for tutor improvement. With the exception of tutor surveys, other assessment types—such as client and exit surveys or self-assessment—seem to evaluate the tutoring program more generally rather than the effectiveness of the ongoing education opportunities specifically. Concerned that perhaps the survey did not accurately capture the assessment of ongoing education that is occurring, I made sure to ask about it in the interviews. Given that some writing centers from this study do not survey their tutors after meetings or training sessions, it seems likely that the number of writing centers currently assessing their ongoing education is actually less than 39%.

Ongoing Tutor Education examples and Principles: Interviews with Writing Center Directors

In addition to helping verify what the survey responses seem to reveal regarding patterns of ongoing tutor education, the interviews help me understand more about the why and the how—why writing centers offer their specific models of ongoing education; how they are conceptualized, implemented, and assessed (the surveys did not provide this level of detail); and how their models have evolved to meet the needs of their tutors, their writing centers, and their institutions. (See interview questions.) Some directors requested anonymity, so I adopted a standard, generic naming practice for all. Interview participants came from each of the institution types in Tables 1 and 2, with the exception of secondary schools. Following a descriptive and holistic analysis of the interviews, I coded the responses into three broad categories: education that involves tutors in the writing center beyond their tutoring work (what I call "deep involvement"), education that develops tutors as leaders, and assessment.

Deep Involvement in the Writing Center

Directors spoke repeatedly of how to motivate tutors to get involved in the center, beyond direct tutoring. They provided examples of tutors serving on committees to plan aspects of the center's work or running the day-to-day operations. In terms of ongoing education specifically, I heard examples of tutors having a great deal of autonomy and authority; for example, at a private, STEM-focused liberal arts college, the tutors have full control over the weekly meetings as the center is run as a "classical collective." Each tutor signs up to run one meeting during the term. And because the director does not always know the topic of the weekly meetings in advance, she must relinquish control, which she is happy to do. In another example, a regional comprehensive writing center has a complex committee structure; the committee structure feeds directly into ongoing education as committees research relevant topics, such as "understanding how multiple languages work and what's an accent" and then use their findings for "training with the whole group, or [...] continued training with the folks who are just hired." And I heard many examples of tutors getting more deeply involved by running activities, leading discussions to share their disciplinary expertise, and writing modules for CRLA or handouts for center use.

Developing Tutors as Leaders

By inviting tutors to get involved with the day-to-day running of the center and with the ongoing development of their peers, directors are also encouraging tutors to seek out leadership opportunities and to develop leadership skills. Mentoring is one such leadership skill. Several of the directors I interviewed ask their experienced tutors to mentor new ones; one director at a Research 1 described how mentors meet with the tutors weekly and then meet with the director to report on what was discussed and to troubleshoot any issues. The director guides the mentors to see parallels between their mentoring work with fellow tutors and their writing center work with students. The center uses a mentor handbook that reviews the philosophy and practice of mentoring and focuses on the ways mentors can encourage tutors to reflect on their tutoring practice; the handbook was prepared by the director and tutors.

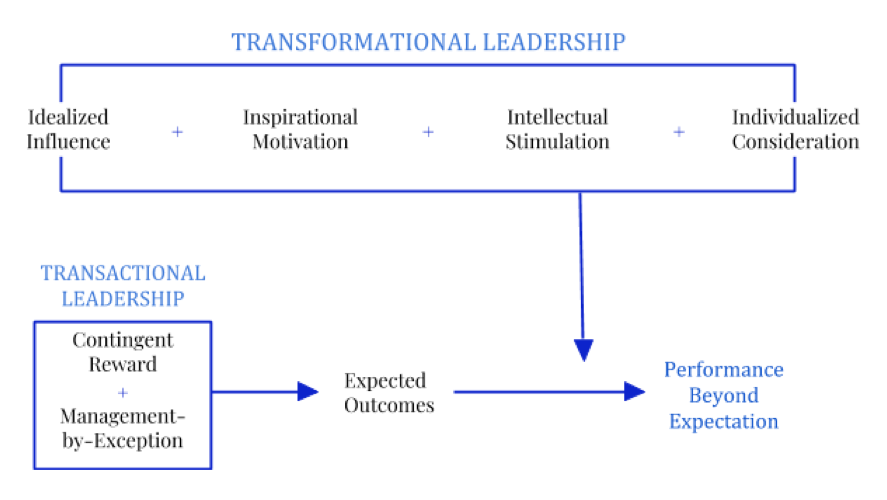

In another example at a CRLA-certified community college writing center, tutors can take on leadership roles when they reach level three certification. The director runs a "leadership institute," which brings new leadership staff together with existing leaders to "talk about the challenges they've had and how they dealt with them." The director introduces them to leadership models, particularly the transformative leadership model—discussed in Komives et al. and represented in Figure 2—as well as other models, such as service.

|

| Figure 2. Components of transformational leadership, compared to the simpler transactional leadership model. Adapted from Northouse, p. 170. |

Examples like this show an orientation toward ongoing education that focuses on tutors as members of a professional organization. While directors voiced a repeated commitment during the interviews for tutor involvement and leadership, a great deal of variation existed beyond this. For instance, directors varied in how they conceptualize ongoing education in relation to an initial course or orientation. For some, the ongoing education is a just-in-time response to tutors' needs; for others, it progresses towards a deepening of tutors' skills, confidence, or expertise; and for others, it is designed to move tutors from practical experience toward inquiry-based research. My sense is that there are a few reasons for this variation: one is how much time the tutors and directors have to undertake education initiatives, another might be budgetary constraints, and a third is what works best for local context and culture. Another variation is what Elisabeth H. Buck describes as "director background" in her chapter for this collection, "From CRLA to For-Credit Course: The New Director's Guide to Assessing Tutor Education." Summarizing previous research by Caswell et al. and Ianetta et al., Buck notes two different approaches to tutor education: one informed by a scholarly background in rhetoric/composition, the other a more practical "first-hand" approach by directors from other backgrounds.

In addition to a focus on professionalizing student staff, directors discussed the continual need to adjust and revise their ongoing education even in writing centers that are CRLA certified and thus have tutors working through standard training modules. The interviews revealed education models with multiple moving parts, emphasizing that many directors continue to experiment with different ways to develop their tutors.

Several directors also spoke of working within the affordances and constraints of their institutional contexts. One director at a public Research 1 discussed the benefits of being well-funded and supported: "We are very fortunate that we can pay our tutors for this much training. I think that there are institutions that just couldn't afford to do this. So we do this kind of training because we can do it." But constraints emerged in terms of limits to what some writing centers can offer to develop their tutors. One director, also at a public Research 1, spoke about her years-long struggle to have a course approved. Thus, political or institutional factors—such as the status of the writing center on campus, the director's position, or how the curriculum is arranged—may impact what can be accomplished in tutor education, factors worthy of further examination.

Involving tutors in the running of the writing center and developing tutors as leaders in the center, it seems, suggest a focus on tutors as professional employees more so than as writing experts—though one assumes this is also an implied emphasis. This focus on professionalism, I suggest, helps position writing centers as important sites for developing students as leaders and future members of the workforce; this goes beyond the long-term communication and analytical skills that we know from the Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project are enhanced by writing center work (Hughes, et al.). In "Teaching, Learning, and Practicing Professionalism in the Writing Center," published in this collection, Tom Earles and Leigh Ryan also explore the writing center as a site of professional development.

Understanding More about Assessment of Ongoing Education

Finally, I asked interview respondents to describe how they assess their ongoing education. In their responses, some discussed using surveys to gauge tutors' perspectives on the value of training sessions or meetings. More frequently, and similar to the  responses I saw in the surveys, directors talked about how they assessed their centers' overall effectiveness rather than how they assessed the ongoing tutor education specifically. This focus, although it might fail to value the specific assessment of tutor education, does suggest that tutoring itself—in addition to the courses, meetings, and observations—is understood as an important site of ongoing education. From this perspective, then, assessment should address everything tutors experience (including working in the writing center, as well as attending meetings, being observed, etc.) that helps build their expertise. With this holistic view of assessment in mind, directors describe some different models for assessing their programs:

responses I saw in the surveys, directors talked about how they assessed their centers' overall effectiveness rather than how they assessed the ongoing tutor education specifically. This focus, although it might fail to value the specific assessment of tutor education, does suggest that tutoring itself—in addition to the courses, meetings, and observations—is understood as an important site of ongoing education. From this perspective, then, assessment should address everything tutors experience (including working in the writing center, as well as attending meetings, being observed, etc.) that helps build their expertise. With this holistic view of assessment in mind, directors describe some different models for assessing their programs:

- Exit interviews. At a private liberal arts college, each tutor is interviewed by the director before they graduate. The director wants to know what specific trainings are helpful, how their views of the writing center have evolved, and how the tutors feel about recent changes.

- Multi-part assessment. At a regional comprehensive, multiple instruments are used to gather information for assessment. A tutor-led committee works with the director to analyze client surveys, coordinate seminanual peer tutor observations and annual tutor self-assessments, and run tutor focus groups.

- Program review.* A community college writing center program review focused on tutors' perceptions of their tutoring skills and abilities in different areas. The writing center is CRLA certified, so the survey looked for tutors' growth as they progressed from level one to level three. The results showed that tutors did improve in their ability to answer questions about tutor competency, an indirect measure of tutor development.

*See program review questions and rubric here.

Overall, survey and interview responses lead me to suggest that effective models for assessing ongoing education are those that are tailored to meet local needs; that align tutor experiences with assessment instruments (for instance, surveys after training sessions or peer observations); and that focus specifically on assessing how the ongoing education is achieving its aims.

Another assessment example is in Elisabeth H. Buck's chapter in this collection, in which she discusses how to use assessment to argue for a new a tutor education program. She describes the issues she encountered with a CRLA-certified writing center. Like Carpenter et al. also in this collection, Buck questions the value of certification not directly anchored in writing center experience. Buck assessed the CRLA-approved training using tutor survey responses and used the results to successfully propose adding in a required for-credit course for all writing tutors.

Smart Practices and Recommendations from Directors

I ended each interview by asking the director what they believe are the smart practices for developing ongoing tutor education. Smart practices acknowledge the important adaptation work of implementing practices recommended from other contexts. Coined by Eugene Bardach, who writes about problem-solving, "'smart practice' underlines the fact that any practice worth special attention [should] have something clever about it. It is this 'something clever' that the researcher must analyze, characterize in words, and appraise as to its applicability to the local situation" (109). From all the advice the directors offered across multiple interviews, three common smart practices emerged.

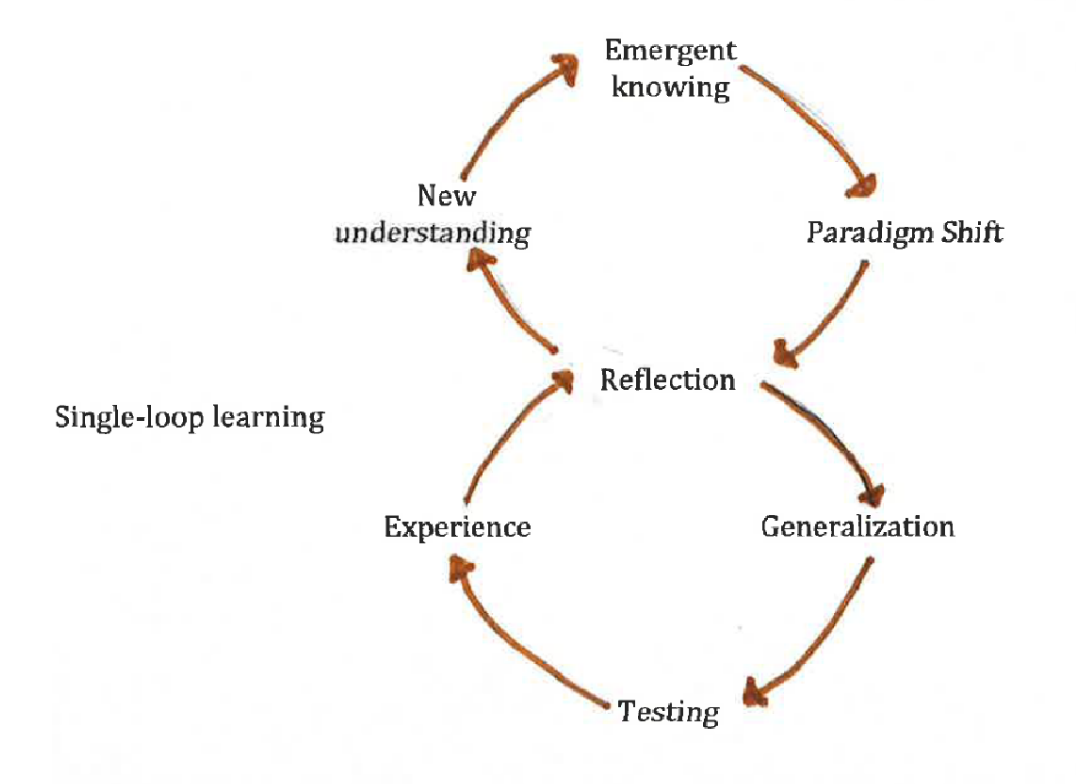

Encourage reflection. Reflection is a touchstone of ongoing tutor education, as demonstrated in the number of writing centers that incorporate observations and self-evaluations. Directors highlighted the importance of "building space into [tutors'] paid time to reflect and talk to each other about what's happening in their sessions" and for the need to "leave space for tutors' dialogue." One director spoke about using the concept of double-loop learning, from Chris Argyris and Donald A. Schön and presented in Figure 3, to encourage tutors to reflect on the why, as well as the what and the how, of tutoring strategies. This concept is also discussed in Hall with specific reference to writing center work. Writing enter direcspantors, too, also need to reflect on why, what, and how they educate their tutors, one director suggested.

|

| Figure 3. Double-Loop Learning (figure-eight double-loop), which includes single-loop learning (bottom loop). Source: Brockbank and McGill. |

Balance consistency and flexibility. While several directors spoke of consistency and flexibility, the balance of these elements differs for different writing centers. Some directors lean toward flexibility: "be willing to test and try new things"; "be willing to adapt to tutors' needs and just-in-time issues"; and "be flexible with accepting suggestions from tutors about learning or development opportunities going on around campus as part of their ongoing training." Other directors emphasized the need for balance: "mixing up [modules] creates a chance for new people to learn from the long-time people and the long-time people to stay fresh. We are able to bring in new ideas and new pieces but we can also have those pieces that work well to teach certain things and we can keep those and use them again and again and again—it helps keep consistency in our program." Another director leans more toward consistency; she spoke of "refining" rather than continually "rethinking" and discussed the need to be "grounded in core principles" and to make sure that any changes are "grounded in beliefs about writing and writing center practice."

Cultivate tutor buy-in. By far, the most common smart practice suggested was to cultivate tutor buy-in. Directors have a range of suggestions for following this practice, emphasizing tutor support, involvement, and ownership. One community college director stated, simply, the need to "put tutors first"; she continued: "they work hard for me, they put a lot of time and effort into their consulting, some of them with very little experience. So they come first and knowing that gives them agency." Another director emphasized the need to "flatten the hierarchy," by "listen[ing] to your tutors and creat[ing] an environment where they feel comfortable talking to you. Invite them to share [their ideas] with you and show that their voice matters and get them involved [at] the planning stages or the implementation." Directors also emphasized the importance of listening to tutors, of "using feedback from tutors to drive future training" and being "open to recommendations and evaluations of the program." One director pushed this further, stressing the need for "more than just input/suggestions"; instead, she urged: "have tutors participate/ lead sessions, and speak from their interests and expertise." Her suggestion echoes the peer-led discussion of readings on tutoring concepts presented by Jessa Wood in "Modelling Peerness: Undergraduate Peer Tutors Leading Education for New Tutors." One director at a Research 1 articulated the reason for involving tutors in the training: "they have to see the value in it and they need to feel that it's not a top-down thing." Another community college director explained the pay-off from tutor buy-in: "they are truly invested in the work and in inspiring and advocating and empowering because they are the ones who really create the culture of the center and inspire those who are new to take on these roles. My new tutors are already excited by week 4 for the possibility of taking on new roles."

Limitations of Study

This study paints a broad picture of tutor education, leaving space for several areas of additional research. Further study is needed to examine how institutional contexts and constraints help or hinder a writing center's ability to offer a robust tutor education program and how a lack of ongoing tutor education might impact the center's ability to effectively serve its campus. In addition, my research found few examples of assessment that specifically evaluated ongoing education opportunities or evaluated ongoing education outcomes in relation to the initial course or orientation. Yet such assessment models surely exist, and we need more published examples of them. Examples will help WCPs conceptualize the design and scope of their own assessment, whether it is for internal evaluation purposes or for external review or accreditation. One caveat of this study is that it is only as representative as the WCPs who took it; while the response rate was high and the interviews help contextualize the survey data, the study is still a snapshot of what those who took the survey do. Regional comprehensive universities are underrepresented in this study, for instance; if they were better represented, the overall picture of ongoing tutor education might look different.

One of my goals was to learn more about how writing centers contextualize or articulate their ongoing education in relation to an initial course or orientation. However, the survey responses did not help me understand how ongoing education is scaffolded or connected thematically or otherwise over a period of time. Scaffolded models do exist, of course, such as those discussed by Lisa Cahill et al. in "Developing Core Principles for Tutor Education" and Sarah Peterson Pittock and Erica Cirillo-McCarthy in "Cross Tutor Training in a Writing and Speaking Center," two chapters in this collection. Cahill et al.'s chapter describes how a team of writing center administrators from five campuses at Arizona State University developed a model for ongoing tutor education based on The Framework for Success in Postsecondary Education's Habits of Mind. The administrators introduced the habits at initial training and then focused on one or more in subsequent meetings and self- and peer-evaluations, building a coherent and connected education model over a period of time. Cirillo-McCarthy and Pittock present their rationale for a cohesive curriculum designed to build connections and share practice among undergraduate, graduate, and professional tutors of writing and oral communication.

Recommendations and Conclusion

While individual writing centers should never lose sight of the need to tailor their ongoing education to suit their specific needs and contexts, I also recommend a cohesive, scaffolded approach to tutor education, so that the tutors can work their way along a developmental trajectory and can see the connections between initial and ongoing education. In addition, and perhaps most importantly, ongoing education benefits from tutor involvement at all levels—from the original design, to implementation, to assessment. Though this recommendation is obvious to WCPs, it's worth keeping in mind as a smart practice, especially when political or institutional constraints might force a WCP to limit what their tutors can do outside of direct tutoring.

While individual writing centers should never lose sight of the need to tailor their ongoing education to suit their specific needs and contexts, I also recommend a cohesive, scaffolded approach to tutor education, so that the tutors can work their way along a developmental trajectory and can see the connections between initial and ongoing education. In addition, and perhaps most importantly, ongoing education benefits from tutor involvement at all levels—from the original design, to implementation, to assessment. Though this recommendation is obvious to WCPs, it's worth keeping in mind as a smart practice, especially when political or institutional constraints might force a WCP to limit what their tutors can do outside of direct tutoring.

While a wide variety of approaches to tutor education exist in the field, some commonalities emerge from the survey and interviews collected for this study. First of all, ongoing education is pervasive, offered by the majority of writing centers who participated in this study. If initial education is often a place to introduce theory and research, ongoing education seems focused more on tutoring practice, application, or reflection. (While there are ongoing education models that focus on tutor research, they are less common according to these survey responses.) As mentioned previously, ongoing education is often discreet and just-in-time, designed to meet the tutors' immediate needs as they encounter specific tutoring challenges. In addition, most directors suggested that without tutor buy-in, ongoing tutor education cannot succeed. While it might be easier to adopt a boilerplate education model, directors are instead continually imagining and iterating their approach to the tricky task of developing an education model that works within their contexts and for their tutors.

1 (back to text) A word about terms: in this article, I use both "training" and "education" even though the field has generally moved toward the term "education." In The Writing Center Journal, the last article with tutor training in the title is Peter Hawkes' 2008 "Vietnam Protests, Open Admissions, Peer Tutor Training, and the Brooklyn Institute: Tracing Kenneth Bruffee's Collaborative Learning"; tutor education started to appear in titles from 2010 with Sarah Nakamaru's "A Tale of Two Multilingual Writers: A Case-Study Approach to Tutor Education."

2 (back to text) Of the n=164 survey respondents, 31% were 4-year liberal arts colleges, 23.9% were regional comprehensives, 26.5% were research intensive/extensive (research 1), 13.5% were 2-year post-secondary, 1.3% were secondary schools, and 3.9% other. Sixty-two percent were public and 38% private institutions, and four responses were from schools outside the U.S. The survey received no responses from elementary or middle school writing centers. Although I did not ask a question about whether the writing centers were stand-alone or part of a learning center or learning commons, of the respondents who listed their names, I was able to determine that 16% are part of a learning center/commons.

3 (back to text) For example, in response to the question about different types of tutor education—"If you selected 'other' to the question, 'which of the following do you offer for your undergraduate tutors/tutors,' please explain"—one respondent wrote: "Writing tutors have an internship (one month while enrolled in a credit course) and a practicum (reading and responses during their first working semester)." I coded this as "internship" and "practicum."

Works Cited

In addition to the sources cited in this article, the directors I interviewed also provided me with a list of recommended resources on leadership and reflection as well as badging, a visual demonstration of incremental learning offered through course management systems and other online platforms.

Argyris, C., and Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective, Addison-Wesley, 1978.

Bardach, Eugene. "Part 3, 'Smart (Best) Practices' Research: Understanding and Making Use of What Look Like Good Ideas from Somewhere Else." Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving. 4th ed. CQ Press, 2012, pp. 109-24.

Bell, Katrina. "Our Professional Descendents: Preparing Graduate Writing Consultants." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Bell.html.

Brockbank, Anne, and Ian McGill. Facilitating Reflective Learning through Mentoring and Coaching. Kogan, 2006.

Buck, Elisabeth H. "From CRLA to For-Credit Course: The New Director's Guide to Assessing Tutor Education." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Buck.html.

Cahill, Lisa, et al. "Developing and Implementing Core Principles for Tutor Education: Administrative Goals and Tutor Perspectives." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Cahilletal.html.

Carpenter, Russell, et al. "Understanding What Certifications Mean for Writing Centers: Analyzing a Pilot Program via a Regional Organization." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Carpenteretal.html.

Caswell, Nikki, et al. The Working Lives of New Writing Center Directors. Utah State University Press, 2016.

Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and National Writing Project. Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing. CWPA, NCTE, and NWP, 2011. http://wpacouncil.org/framework Accessed 19 Aug. 2018.

Denny, Harry. "Queering the Writing Center." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 30, no. 1, 2010, pp. 95–124.

Dvorak, Kevin. "The Professionalization of a Writing Center Staff through a Professional Writing Internship Program." Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 7, no. 2, Spring 2010.

Earles, Tom, and Leigh Ryan. "Teaching, Learning, and Practicing Professionalism in the Writing Center." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/EarlesRyan.html.

Hall, R. Mark. "Problems of Practice: An Inquiry Stance toward Writing Center Work." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 37, no. 5-6, 2013, pp. 1-4.

---. "Theory In/To Practice: Using Dialogic Reflection to Develop a Writing Center Community of Practice." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, 2011, pp. 82-105.

Hawkes, Peter. "Vietnam Protests, Open Admissions, Peer Tutor Training, and the Brooklyn Institute: Tracing Kenneth Bruffee's Collaborative Learning." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 28, no. 2, 2008, pp. 25–32.

Hill, Heather N. "Tutoring for Transfer: The Benefits of Teaching Writing Center Tutors about Transfer Theory." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 3, 2016, pp. 77-102.

Hughes, Bradley, and Melissa Tedrowe. "Introducing Case Scenario/ Critical Reader Builder: Creating Computer Simulations to Use in Tutor Education." The Writing Lab Newsletter, Vol 38, No 1-2, 2013, pp. 1-4.

Hughes, Bradley, et al. "What They Take with Them: Findings from the Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 30, no. 2, 2010, pp. 12–46.

Ianetta, Melissa, et al. "Polylog: Are Writing Center Directors Writing Program Administrators?" Composition Studies, vol. 34, no. 2, 2006, pp. 11-42.

Johnson, Karen G., and Ted Roggenbuck, editors. How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection. 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/JohnsonRoggenbuck.html.

Kail, Harvey, et al. The Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project. Accessed 15 Aug. 2018.

Komives, Susan, et al. Leadership for a Better World: Understanding the Social Change Model of Leadership Development. Jossey-Bass, 2009.

Nakamaru, Sarah. "Theory in/to Practice: A Tale of Two Multilingual Writers: A Case-Study Approach to Tutor Education." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 30, no. 2, 2010, pp. 100–23.

Northouse, Peter Guy. Leadership: Theory and Practice. 7th ed. SAGE, 2015.

Pittock, Sarah Peterson, and Erica Cirillo-McCarthy. "Let's Meet in the Lounge: Toward a Cohesive Tutoring Pedagogy in a Writing and Speaking Center." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/PittockCarillo-McCarthy.html.

Saldaña, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. SAGE, 2009.

Wood, Jessa. "Modelling Peerness: Undergraduate Peer Tutors Leading Education for New Tutors." WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 42, no. 1-2, 2017, pp. 26-29.

Writing Centers Research Project. https://owl.english.purdue.edu/research/research.html. Accessed 15 Aug. 2018.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Harry Denny for permitting me to contact Writing Center Research Project respondents to invite to take my survey. Thanks to my Elon University writing group colleagues Heather Lindenman and Jennifer Eidum and my collaborator-on-other-projects Dagmar Scharold at the University of Houston-Downtown for feedback on sections of drafts, and to Elon University Writing Center Consultants Rachel Coose and Natalie Nielsen for help with tables and additional research.

BIO

Julia Bleakney is Director of The Writing Center in the Center for Writing Excellence at Elon University, and an Assistant Professor. She is 2018 and 2019 co-chair of the International Writing Centers Association Summer Institute and co-chiair of the 2019-2021 research seminar on Writing Beyond the University: Fostering Writers' Lifelong Learning and Agency. Her research interests focus on writing center mentoring, tutor education, and transfer.