CHAPTER THREE

Enter the Dragon: Graduate Tutor

Education in the Hall of Mirrors

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Craig Medvecky

Loyola University Maryland

Introduction

If you are a martial arts movie buff, chances are one of your favorite scenes is the climax in Enter the Dragon—in which Bruce Lee chases the villain, Han, into a Hall of Mirrors where Han's image multiplies hundreds of times over. Suddenly, Lee does not know which way to turn. His kung-fu is neutralized. Han knows the maze. He darts in and out dealing blows and disappearing before Lee can react.

|

| Figure 1. Bruce Lee in Enter The Dragon (1973). |

As a writing center administrator, I can relate to Lee's predicament at this moment in the film. When I chase the problem of how best to prepare my graduate tutors to work in the center, it seems as though I, too, run into a hall of mirrors. Suddenly my initial focus, tutor education, recedes and the multifaceted image of graduate writing support rises up to replace it. After all, how can I design and implement a course for my graduate tutors until I know of what kinds of support the writing center should provide to graduate students? Should the center offer more workshops, or fewer workshops, or online workshops? Should my tutors learn more about discipline-specific support or spend the time and effort deepening their generalist practice? Should we spend our energy educating departments and programs about what we offer or change our services based on the idiosyncratic needs of each specific graduate program?

To back up for a moment, I should note that on our campus we train graduate tutors to work with graduate students and undergrad tutors to work with undergrad students. Our center, like many centers in the U.S., employs a generalist approach to peer tutoring, such as espoused in The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors or The Longman Guide to Peer Tutoring, the essence of which holds that a properly trained peer tutor can work effectively with any writer from any course at any stage in their writing process. In that regard, our undergraduate tutor education focuses almost exclusively on the study and application of these principles, which when working, enable a sophomore biology major to effectively tutor a senior working on a capstone literary analysis, even if the tutor herself has never taken a single English class. However, we also train graduate tutors to work with exclusively with a graduate student population that is largely non-residential, working during the day and taking evening classes, and typically less connected to campus and professors. In these circumstances, I have become convinced that graduate writing support is a much different endeavor from undergraduate peer tutoring. Furthermore, significant scholarship now suggests that a singular focus on generalist peer tutoring may not be enough support for graduate-level writers. In turn, that underscores my need to understand graduate writing support holistically, since I may not be able to educate my graduate tutors using exactly the same methods I employ with my undergraduate peer tutors. To better understand how to educate graduate tutors, this chapter examines three current approaches to graduate tutor education and synthesizes a set of possible learning outcomes for tutor education within the context of broader institutional support.

Graduate Writers Need More Systemic Support Structures

In "The Problem of Graduate-Level Writing Support: Building a Cross-Campus Graduate Writing Initiative," Steve Simpson points out that "the problem [...] is a systemic one," necessitating partnerships that span university departments. The de-centered and highly specialized nature of graduate programs, coupled with both the increased ability of learners to structure their own courses of study and their need to meet increased demands for professionalism in a global context, necessitates a more complex and flexible approach to support for grads than for undergrads. With compelling analysis of empirical studies and current literature, Simpson argues for long-term, flexible, integrated approaches to supporting graduate students—the most successful of which will involve collaboration and coordination between writing centers, graduate offices, and graduate departments (106).

Simpson is not alone in this view. Sarah Summers, in her dissertation, Graduate Writing Centers: Programs, Practices, Possibilities, found graduate writers to be far different from undergrads in the circumstances under which they work and the writing they produce. Graduate students, she argues, are less engaged with the values of the institution because their focus tends to be outside and beyond the institution (10). In many ways the institution becomes transparent to the graduate student. Summers mainly focuses on grad students who do not live in the campus community, but rather attend classes and return home. For such students, classes and degrees-in-process are a purposeful means to specific career goals for which graduate students must carve out time from the rest of their lives. Summers goes on to paint a picture of an educational crisis in full swing, directly linking poor performance at the graduate level nationwide to a lack of writing support. Through her study of Council of Graduate Schools reports, she notes that only 57% of doctoral candidates finish their degree within ten years, a number that drops to 49% in the Humanities (9), citing widespread recognition that students at the dissertation stage feel isolated and vulnerable, and consequently, often fail to remain on track (13). Meanwhile she notes that 3.4 million students over age 35 will enroll in grad school by 2018, which is an increase of almost 90% over the past 30 years.

At the same time, as Daniel Mahala and Jody Swilky point out, professors tend to offer less assistance to graduate students than to their undergraduate counterparts because graduate faculty tend to be more focused on their own research, to view their fields as competitive, and to feel the onus is on the graduate student to learn and achieve independently as a rite of passage into the discipline. What ensues is a recipe for friction. Graduate students tend to be less clear than undergraduates regarding what is expected of them academically and institutionally because they tend to spend less time on campus engaged with faculty. Furthermore they are less concerned with institutional expectations in the first place because today's graduate student is focused on professionalization. The degree-granting institution fulfills both an educational mission and a gatekeeper function, limiting access to a professional community (and by extension, higher pay, greater job security, greater mobility, etc.) until specific requirements are met. Admittedly, these statements are generalizations. Of course, they cannot describe every graduate student or every university. Nonetheless, these are significant national trends observed by reliable researchers and borne out on my own campus.

In this context, Simpson's and Summers' studies of graduate writing support reveal the need for a collective effort, a network of support that goes beyond the writing center. Adopting their perspective implies the need for graduate writing centers to create/identify a graduate-specific role for themselves and their tutors within the larger, university-wide task of supporting graduate-level writing. This may seem at first like a weakening of the writing center's position on campus as a locus of writing expertise; however upon closer examination I believe taking a collaborative approach can be just as empowering. Defining the roles that the writing center fills allows the center in turn to understand more clearly the work its graduate peer tutors will be doing, and subsequently, to develop and refine a system of tutor education that helps those tutors to be more successful.

In this context, Simpson's and Summers' studies of graduate writing support reveal the need for a collective effort, a network of support that goes beyond the writing center. Adopting their perspective implies the need for graduate writing centers to create/identify a graduate-specific role for themselves and their tutors within the larger, university-wide task of supporting graduate-level writing. This may seem at first like a weakening of the writing center's position on campus as a locus of writing expertise; however upon closer examination I believe taking a collaborative approach can be just as empowering. Defining the roles that the writing center fills allows the center in turn to understand more clearly the work its graduate peer tutors will be doing, and subsequently, to develop and refine a system of tutor education that helps those tutors to be more successful.

Three Examples of How Institutional Context Affects Tutor Education Programs

At this point, I have advanced the notion that university leadership should be involved in developing an integrated, campus-wide system of supports for graduate writers. One wonders, logically, what should that support system include? The vexing answer may be that it depends. To unpack those dependencies, I want to explore three approaches to graduate writing support rooted in the writing center and then examine their implications for tutor education. By doing this, I hope to convince readers that institutional context matters significantly in planning and delivering peer tutor education for graduate students. To that end, this analysis will attempt to synthesize a set of learning aims for graduate tutor education that could allow writing centers and graduate tutors to function more effectively and more flexibly within a campus-wide system of graduate writing supports. Certainly, there will also be a piece of the puzzle that must be solved locally as writing centers integrate with the other sorts of graduate support services available on each individual campus, such as program specific mentors, content tutors, faculty advisors, practitioner liaisons from their intended field, or other types of support for issues like time management and wellness.

1. Educating Graduate Tutors for Writing In The Disciplines

Heather Blain Vorhies contends that effective graduate tutoring depends to some degree on knowledge of genre and discourse conventions at the subject level. In "Building Professional Scholars: the Writing Center at the Graduate Level," Vorhies notes a lack of writing instruction at the graduate level campus-wide, which creates a need that increasingly falls to the writing center to meet; i.e., placing more demands on tutors to function as instructors.

The problem that Vorhies is trying to crack open at the University of Maryland is how to prepare grad tutors to be helpful in a wider range of writing contexts than undergraduate tutors encounter—even as a larger question lingers at the institutional level: what is the best way to help graduate students to succeed in writing? Vorhies' voice in the conversation represents those exploring the idea that "graduate tutors should have disciplinary expertise" (6). The assumption underlying this school of thought is that form/genre matter in graduate writing a good deal more than in undergraduate work, and further, that the forms of graduate writing are more complex and nuanced than those of undergraduate papers. The rub for Vorhies is that there are 288 different graduate degree granting programs at her institution. Naturally it is unrealistic to expect to staff a field of tutors who have expertise in the writing conventions of all those areas. Of course Vorhies isn't talking about content expertise. She advocates a writing-in-the-disciplines approach. Even so, this still calls for a level of expertise beyond the casual awareness that might be created through occasional staff meetings or sponsored talks. In Vorhies' experience, it can be too difficult for a tutor to provide effective help with a literature review if they themselves have never seen one before and don't know the form.

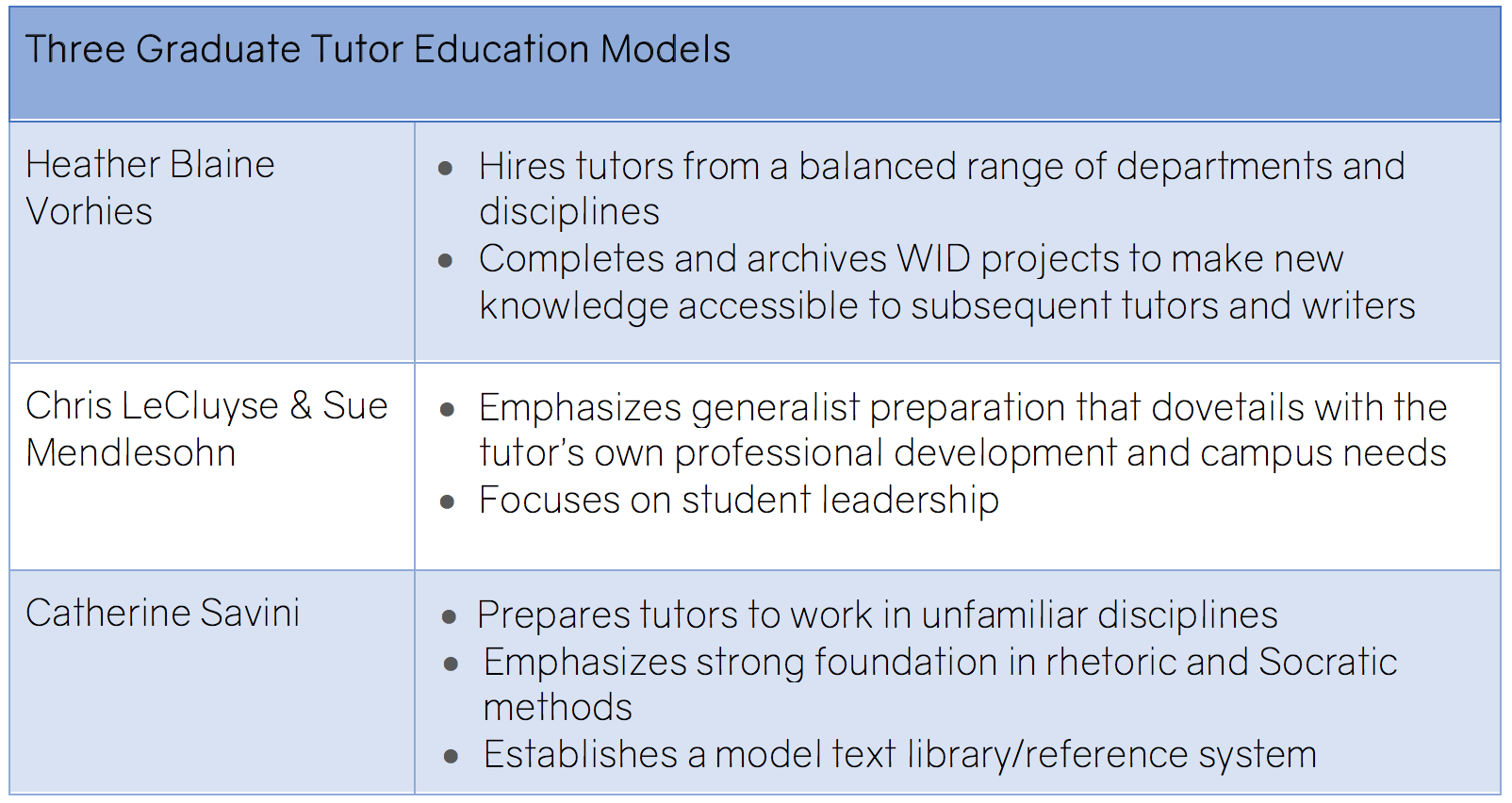

So what does that mean for a program of tutor education once Vorhies identifies the goal of providing tutors with disciplinary expertise? Insofar as Vorhies explores that topic, we know that she hires her tutors from a balanced range of departments and disciplines and tasks them with WID projects in their field that make a connection between their own goals as graduate students and their work in the writing center (7-8). Further, they complete and archive their WID projects to make that new knowledge portable to subsequent tutors and students. This seems like a move to connect graduate writers with department/program-based support and mentorship as well as an effort to provide more genre and content expertise. Beyond that, Vorhies does not address the topic of how to prepare tutors for WID discourse. On one hand, her tutors may bring knowledge from their own disciplines, which they then develop through independent projects, but it is unclear how, or if, they develop knowledge in unfamiliar disciplines, and if so, how many different disciplines? As a result, directors wishing to move in this direction would need to answer these questions in conjunction with their development of a curriculum for teaching writing in the disciplines to tutors.

2. Tutor Education As Engaged Self-Practice and Professional Development

In "Training as Invention: Topoi for Graduate Writing Consultants," Chris LeCluyse and Sue Mendlesohn suggest that struggles with graduate tutor education are not due to a lack of received subject knowledge on the part of the tutor, but rather a lack of meaningful engagement with accepted generalist peer tutoring practices. To explicate, the authors present two case studies. In the first, what they call the old model, they describe a situation familiar to many in which training takes place in regular weekly staff meetings, but as the staff grows attendance becomes spotty (108). Meetings dwindle in size. The increasingly beleaguered director shifts the bulk of training to a week-long session in August, but in doing so, inadvertently sends a message that tutoring is like riding a bike: once a few simple points are mastered tutors are all set (110). Then the director moves to longer summer orientations and topics-based workshops, but these new requirements make recruiting difficult and continue to meet with many of the original scheduling challenges.

In response to their strawman, LeCluyse and Mendlesohn then propose the concept of graduate tutor training based on the rhetorical theory of argument. Their second case study, the new model, or "training to meet consultant needs," positions the educational materials as an argument aimed at graduate tutors, making the case to the new tutors that they both need and benefit from training and development in profound ways. The purpose of this appeal is to gain the graduate tutors' participation in a rigorous, ongoing, practical engagement with generalist peer tutoring.

LeCluyse and Mendlesohn factor in the local rhetorical situation including understanding of the specific needs of the audience (i.e. the current cohort of graduate tutors) and the institution. In other words, they urge: don't forget about your graduate students as the audience of the training and just require what the institution needs. They exhort directors to package training as a persuasive act. That means knowing the audience as well as their needs, interests and academic specialties; the conditions they work under; the assumptions they bring about tutoring and training and writing; the pressures they face; and the practices they regard as credible—all of which can vary by locality. Once directors understand their workforce, they can craft an argument for professional development that balances grads' emerging professional identities with their writing center work (104-05).

In their new model, they create a center in which the grad tutors develop and run their own training, including programming their own workshops, conducting their own training research and giving talks and presentations amongst themselves. LeCluyse and Mendlesohn deal mainly with the question of how one might conceive and structure tutor education and not the content of that education per se. Although the article does not specifically state it, one can assume the content of the tutor education curriculum adheres largely to the topoi of the undergraduate writing center and its generalist foundation, since the authors note that the center on which the case studies are based "serves undergraduate writers exclusively" (108). However, it is worth noting that for LeCluyse and Mendlesohn, the methods are established but the content of the course is not prescribed because it is developed locally in response to the specific needs of specific tutors on a specific campus.

So where does that leave us? It seems one must be an astute judge of character in the hiring process and a very accomplished rhetorician to persuade such a workforce to commit/invest/believe in the undertaking of a self-guided, contemplative practice in a field that is likely to be only somewhat related to their future career. Certainly, I could relate to the director in LeCluyse and Mendlesohn's first case study for whom circumstances surrounding the education of graduate peer tutors presented more of a logistical challenge than anything. Simply getting graduate tutors to engage deeply with the fundamentals of generalist peer tutoring requires time and consistent effort. That means staff meetings, individual training, peer observations, reflective writing assignments, meetings with the director, practice sessions, engaged or facilitated readings, and a host of other ongoing professional development activities. In addition to that already long list, authors like Vorhies convincingly suggest that our graduate tutor education must do more to prepare tutors for wider-ranging and more complex disciplinary writing. Further, some grad tutors may even need to practice in the online modality, which requires technological literacy, software skills, and education in how peer tutoring changes in a synchronous mediated environment.

Despite the daunting challenge, I think we must not lose sight of LeCluyse and Mendlesohn's thesis: graduate tutor education—generalist or otherwise—must meet the emerging professional needs of the tutors, and those needs must be determined locally. I will come back to this in a moment.

3. Tutor Education as an Encounter with the Unknown

In "An Alternative Approach to Bridging Disciplinary Divides," Catherine Savini seeks a middle-ground, pointing out problems with both a generalist model and a disciplinary specialist model. She agrees that a generalist model of tutoring with its focus on dialogic conversation encounters many problems at the graduate level when tutors run up against unfamiliar formal requirements of advanced disciplinary writing. At the same time, she acknowledges that teaching grad students to be proficient in a variety of disciplinary conventions is a tall order. It seems that she might agree with LeCluyse and Mendlesohn: more received knowledge is not the answer. Presentations or workshops on literature reviews or dissertation proposals oversimplify conventions and present them as static points to be memorized (3). What's more, asking the tutors to learn all of this creates a lot of pressure and anxiety. And who is going to provide this expert knowledge in every genre of every department on your campus? For Savini, graduate writing support simply encompasses too much diversity and too much nuance for one person.

Savini argues that instead we ought to spend our efforts preparing consultants to work with unfamiliar forms and genres. When tutors find themselves in an unfamiliar discipline they must be able to "teach their peers how to find their own way" (3).

The lynchpin to Savini's idea is a repository of model texts in various graduate disciplines that illustrate the formal conventions of that field in context. In this approach, tutor education takes the form of learning how to work with the model texts. This includes gathering, annotating and discussing the texts. For Savini, the model text library is a good alternative/supplement for faculty visits or guest lectures because it is easier to coordinate and has a longer shelf life for students who cannot always attend meetings. Model texts educate both the writer and the tutor and can be the subject of education activities as well as a living archive for students in person or on the center website. Savini outlines her views on the best approach to graduate tutor education in the following synthesis:

- Tutors must learn to disclose their own lack of experience/expertise to make the student aware without losing the confidence of the student (3).

- Tutors must learn to pose the right diagnostic questions to gauge the writer's own comfort level or knowledge of the formal/generic requirements of the assignment (3).

- Tutors must learn to (and show students how to) work with model texts (4).

Like Vorhies and LeCluyse and Mendlesohn, Savini offers valuable insight. She has come up with a synthesis for tutor education that she presents as a best practice, stating, "writing centers that teach tutors and students to actively investigate unfamiliar disciplines avoid the pitfalls that accompany generalist or discipline-specific approaches" (5). Really, this is something new—a third approach to graduate tutor education that focuses on preparing tutors for times in which they find themselves in unfamiliar territory.

When taken together, each of these three tutor education models is quite different, as each director conceives of different goals for their peer tutors within the larger institutional context of graduate writing support on their own campus (See Figure 2 for a summary of these models). Vorhies' model, in a sense, co-locates the graduate writing center within various departments to emphasize the importance of WID in her tutor education program; LeCluyse and Mendlesohn focus on education that builds engagement and commitment with the generalist practice of tutoring by tailoring the education to serve not only the needs of the writing center but also the specific emerging professional needs of the tutors on their campus. Finally, Savini tries to bridge the gap between peer and instructor with the creation and maintenance of an extensive library of model texts.

|

| Figure 2. A summary of the main features in three graduate tutor education models. |

As readers look in on these examples from a wider angle, we see that the field is searching for solutions, having yet to agree on best practices for graduate tutor education. The authors above craft careful responses to their own institutional contexts, but how do we know what will work on our own campus or campuses? Vorhies and Summers both remind us that where top-down programs are yet to be developed and/or budgets are lacking, the writing center is often tasked with filling the void, so it is clear that initiative must be taken. To complicate matters, there isn't a one-size-fits-all solution because there are too many variables in graduate writing support. Am I suggesting that everyone has to reinvent the wheel for themselves? No, far from that.

Identifying Appropriate Tutor Education Practices

Our current research implies that graduate tutor education programs that impart generalist methods exclusively limit tutors' ability to provide the wide range of supports that can be required by graduate writers. This zeitgeist is apparent in the growing body of literature on graduate tutoring as we see directors exploring the ways in which some of the conventional approaches of generalist writing centers bend to the demands for greater support at the graduate level: grammar, proofreading, and directive advice are more acceptable; disciplinary and genre knowledge are valued more highly; and professors and advisors are more revered—and in some cases, more feared (Jordan and Kedrowicz 3).

That being said, I believe that the principles of generalist tutoring remain an important part of peer tutor education at every level. Generalist tutoring approaches are not disposable; rather they must be augmented. Teaching graduate tutors to engage with the practices of co-learning and collaboration seems vital, but how might that look in a graduate-level environment in which there are higher demands for disciplinary expertise and overt instruction? Indeed, the baseline level of required education and development in the generalist model of peer tutoring is already very high for a part-time worker. Peer tutors in our undergraduate center, where these methods are privileged, must complete a 3-credit, 300-level course and intern for 20 hours before they can start work as a peer tutor. Following this initial education, they must convene regularly for development activities and many also participate in professional conferences. Conversely, my graduate center typically staffs 6-8 Graduate Teaching Assistants as tutors. Some work as few as 5 hours per week because that is all their schedules permit. Experience has proven that it is very difficult to get everyone into a room at the same time for any activity, as LeCluyse and Mendlesohn also noted (108), because of legitimate scheduling conflicts with other jobs, night classes, family commitments, etc.

Savini and Vorhies offer important pieces of the puzzle from which we can extract a framework, which, if we accept LeCluyse and Mendlesohn's argument, must then be applied uniquely in each local situation. LeCluyse and Mendlesohn provide guidance on how to implement what we already know about education of generalist methods for graduate staff in exciting and creative ways. They break with the tradition of a "best practice" as something imposed from the top down, from director to tutor. Savini teaches us that we must also prepare graduate consultants to be helpful when they aren't sure or don't know the formal conventions of the piece in question, as this could be a frequent occurrence for graduate tutors. Savini rejects the notion of writing as focused on content over form. And Vorhies urges us to prepare our tutors with as much knowledge of their disciplinary writing habits as we can and to hire from a diverse range of disciplines. She questions the idea of a writing center as merely a generalist dialogue. Whatever conventions, practical problems, or inhibiting ideologies the mirrors might represent on a given campus, directors might need to give themselves permission to shatter some glass.

For directors wondering about specifics—whether/how/how much of graduate tutor education should focus on WAC/WID instruction, for example—one important thing to remember is that your own institutional context—that is, relationships outside of the writing center—necessarily shape the response. Therein lies the crux. The reason we are in the Hall of Mirrors in the first place is the inherent conundrum of how to successfully develop a campus-wide support system for graduate writers, if it is only the writing center that is principally aware of this need.

Defining Graduate Writing Support through Leadership Roles

Before directors can design and implement the most effective graduate tutor education programs, they must know how their services are to integrate into other support structures the campus offers. Only once these connections are in place and understood will the roles of the tutors on a specific campus become clear enough for the directors to develop appropriate effective education. Given the organizational challenge of crafting a support strategy that spans many diverse graduate programs, and in the absence of a cohesive larger vision, the graduate writing center may fall back on generalist peer tutoring exclusively, but that method of writing support seems to be less than ideal based on declining national retention and completion data.

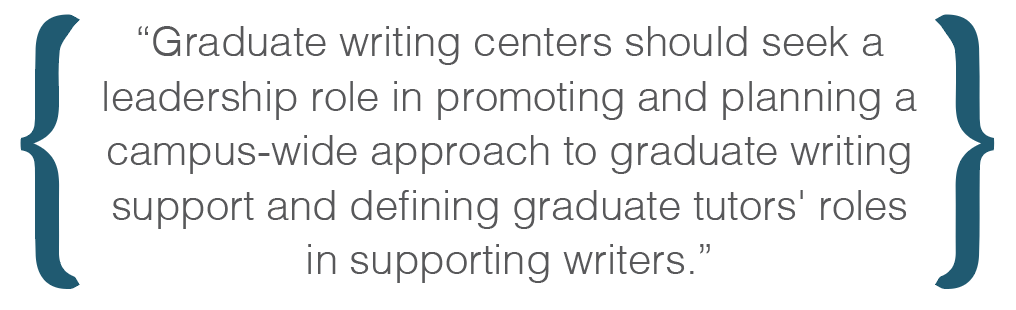

Perhaps, then, graduate writing centers should seek a leadership role in promoting and planning a campus-wide approach to graduate writing support and defining graduate tutors' roles in supporting writers. Existing writing center research can effectively raise awareness and provide actionable agendas for diverse groups of stakeholders, including the Graduate School, Academic Affairs, the Provost, and the deans of all the individual graduate schools, programs, and departments. As Connie Schroeder reminds us in her book Coming in from the Margins, our institutions can ill afford to advance initiatives that clearly dovetail with matters of teaching and learning without the directors of such centers seated at the planning table (2).

Perhaps, then, graduate writing centers should seek a leadership role in promoting and planning a campus-wide approach to graduate writing support and defining graduate tutors' roles in supporting writers. Existing writing center research can effectively raise awareness and provide actionable agendas for diverse groups of stakeholders, including the Graduate School, Academic Affairs, the Provost, and the deans of all the individual graduate schools, programs, and departments. As Connie Schroeder reminds us in her book Coming in from the Margins, our institutions can ill afford to advance initiatives that clearly dovetail with matters of teaching and learning without the directors of such centers seated at the planning table (2).

The need for leadership and action is present at the graduate program level in many universities as U.S. higher education increasingly sees graduate degree enrollment through the business-minded lens of financial opportunity. At the same time, administrations are aware that nationally we are experiencing a crisis of completion and retention simultaneous with a surge in enrollments. From this crisis emerges the opportunity for writing centers and writing programs to offer steering, planning, and consultation in the development or expansion of writing support specific to graduate degree programs. Certainly it makes sense for the writing center to have a seat at the table as these decisions are made.

Once a shared vision of graduate writing support emerges on a given campus, the writing center then has a basis for defining the role that peer tutors should play in that support system. By that point it should be clear the extent to which each participant will provide discipline-specific help, ESL support, professional development, mentoring, and dialogic feedback. Hopefully in defining a campus strategy and allocating resources collectively, all of these tasks won't fall solely on the shoulders of graduate peer tutors. Rather the director and tutors will understand the goals of peer tutoring for that institutional setting, and if/when a writer requests additional help, tutors and staff will know exactly how and where to refer them. These defined roles set the mandate for a range of possible tutor education strategies, which then purposefully incorporate the principles we see emerging in other locally successful models.

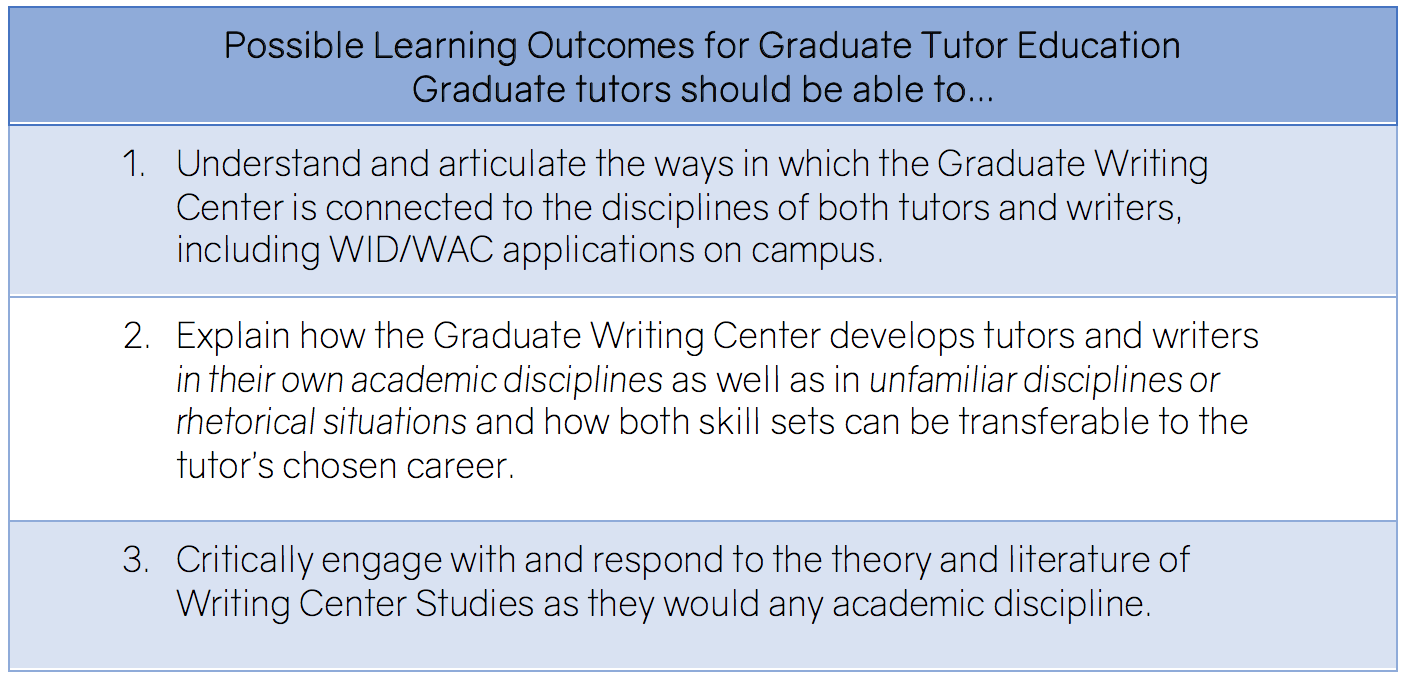

Developing Learning Outcomes for Graduate Tutor Education

In keeping with the notion of the writing center as a site of education and learning driven by research and pedagogy, as opposed to a campus service center, it can be helpful to articulate specific learning goals for tutor education. These learning outcomes serve to guide a campus with many degree programs and help ensure curricular continuity among schools, departments, and individual faculty members. Re-imagining the lessons of Savini and Vorhies in a graduate-level version of LeCluyse and Mendlesohn's training model, the learning outcomes of a new tutor education program might look something like this (see Figure 3):

|

| Figure 3. The author's suggested learning outcomes for graduate tutor education. |

Any potential learning outcomes derived from the case studies presented above, and others as they emerge, should be explored, combined and applied to fulfill local needs. The key to making these goals purposeful and effective is to see them as part of an overarching plan for graduate writing support on campus. Every year the various participants must pursue and refine a shared understanding of their responsibilities for graduate writing support on campus. Only at that point can writing center administrators design an effective graduate tutor education curriculum that incorporates effective generalist practices with emerging knowledge of the discipline in response to the specific and changing needs of their own institution.

A Call for Leadership

In this chapter, I have argued that graduate writing center directors and administrators should take a leadership role in defining the shape of graduate writing support not just in their centers, but particularly across their institutional contexts. On our campus, the journey in and out of the Hall of Mirrors has been ongoing. The learning outcomes for tutor education make for a good start in the center itself, but on our campus, we are still trying to get the campus united behind the common goal of a clear vision for graduate education and graduate writing support. We have faced quite a bit of turnover in the higher levels of campus administration, which has resulted in evolving visions of graduate education. Financial pressures felt across the university have led to more revenue conscious models for graduate programming. And, in recent semesters, the writing center itself has hosted two visiting directors. As an addendum to this piece I have included our writing center's leadership project narrative for people interested in the specific details of our local efforts to engage graduate program stakeholders in the challenge of offering systematic, integrated programs of writing support, but much work remains to be done here.

However, I hope the central point of this paper will not be lost in that I don't believe there is a one-size-fits all solution. Whatever works, or doesn't work, on my campus is a product of the personalities and problems we uniquely face, and as a result, there is no guarantee that our strategies or solutions will have similar results on your campuses. The solution is to engage with other interested parties locally and to create the answers you need on your campus.

Adapting to Change

As it happens, my university is in the midst of significantly restructuring its graduate programs. Four notable and long standing programs have closed their doors in the last two years, while other programs are expanding onto satellite campuses in nontraditional ways. Our writing center has been working to keep pace with these changes and to engage the campus community in conversation about its vision of graduate writing support. We have also been working with various departments to identify and train tutors with a more discipline-specific writing focus so that we can offer support in the programs where it is needed most. To this end we have created a Graduate Fellows program, which we are currently assessing and hope to write about in the near future. Furthermore, the university has begun to offer content tutoring to graduate students for the first time. This service runs from a different academic support unit than the writing center, giving us another clear collaborator on campus. While these programs need ongoing refinement and continued assessment, our initial engagements are invigorating, and we are looking forward to the challenges ahead. If this feels too diffuse for a conclusion, consider that it may be diffusion that is at the heart of this particular problem of how best to support graduate writers.

Works Cited

Council of Graduate Schools. "Graduate Enrollment and Degrees: 2005–2015. Washington, D.C.: Council of Graduate Schools. https://cgsnet.org/graduate-enrollment-and-degrees-2005-2015.

Gillespie, Paula, and Neal Lerner. The Longman Guide to Peer Tutoring. 2nd ed., Pearson Longman, 2008.

Jordan, Jay, and April Kedrowicz. "Attitudes About Graduate L2 Writing in Engineering: Possibilities for More Integrated Instruction." WAC and Second Language Writing: Cross-field Research, Theory, and Program Development, a special issue edited by Michelle Cox and Terry Myers Zawacki, Across the Disciplines, vol. 8 , no. 4, 2011. wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/ell/jordan-kedrowicz.pdf.

LeCluyse, Christopher, and Sue Mendlesohn. "Training as Invention: Topoi for Graduate Writing Consultants." (E)Merging Identities: Graduate Students in the Writing Center, edited by Melissa Nicolas, Fountainhead Press, 2008, pp. 103-16.

Mahala, Daniel, and Jody Swilky. "Resistance and Reform: The Functions of Expertise in

Writing Across the Curriculum." Language and Learning Across the Disciplines, vol. 1, no. 2, 1994, pp. 35-62.

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. 6th ed.,

Bedford/St. Martins, 2015.

Savini, Catherine. "An Alternative Approach to Bridging Disciplinary Divides." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 35. no. 7-8, 2011, pp. 1-5.

Schroeder, Connie M. Coming in from the Margins: Faculty Development's Emerging

Organizational Development Role in Institutional Change. Stylus, 2011.

Simpson, Steve. "The Problem of Graduate-Level Writing Support: Building a Cross-Campus Graduate Writing Initiative." Writing Program Administration, vol. 36, no. 1, 2012, pp. 95-118, wpacouncil.org/archives/36n1/36n1all.pdf#page=96.

Summers, Sarah. Graduate Writing Centers: Programs, Practices, Possibilities. Dissertation,

Penn State U, 2014.

Vorhies, Heather Blain. "Building Professional Scholars: The Writing Center at the Graduate Level." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 39, no. 5-6, 2015,pp. 6-9.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the Loyola Writing Department and the Mid-Atlantic Writing Centers Association for generously funding activities that related to the development of this chapter. Additionally, I would like to thank my colleagues for their careful reading, useful feedback, and guidance throughout the publication process.

BIO

Craig Medvecky is the Associate Director of the Writing Center at Loyola University Maryland. He is a past board member of the Mid Atlantic Writing Centers Association and past co-chair of the Graduating Writing Support Special Interest Group of the International Writing Centers Association.