CHAPTER SIX

Developing and Implementing Core

Principles for Tutor Education: Administrative

Goals and Tutor Perspectives

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Lisa Cahill, Molly Rentscher, Kelly Chase, Darby Simpson, and Jessica Jones

Arizona State University

Arizona State University (ASU) is a large university in the southwestern United States, spanning four physical campuses as well as online degree programs. ASU is also home to University Academic Success Programs (UASP), a department that oversees writing centers, subject area tutoring centers, and other retention and academic support initiatives for freshmen through doctoral students. Each of UASP's campus writing centers and its online writing centers is managed by an individual coordinator who reports to an associate director. Coordinators in the unit collaborate as a part of a cross-campus writing work group to strategize and plan for ongoing program development, tutor education needs, and student support while also collaborating with faculty to support undergraduate and graduate student writing. As a result, in 2015, our team of writing center administrators in UASP realized that some of our ongoing tutor education practices needed to be revised in order to prompt our peer writing tutors to think more critically and personally about writing center principles and practices. Thus, we resolved to make significant and lasting improvements to the ways we educate our tutors. Specifically, we wanted our tutors to think more reflectively and critically about their daily practices and to be able to identify the strategies and mindsets they used to engage students in conversations about writing.

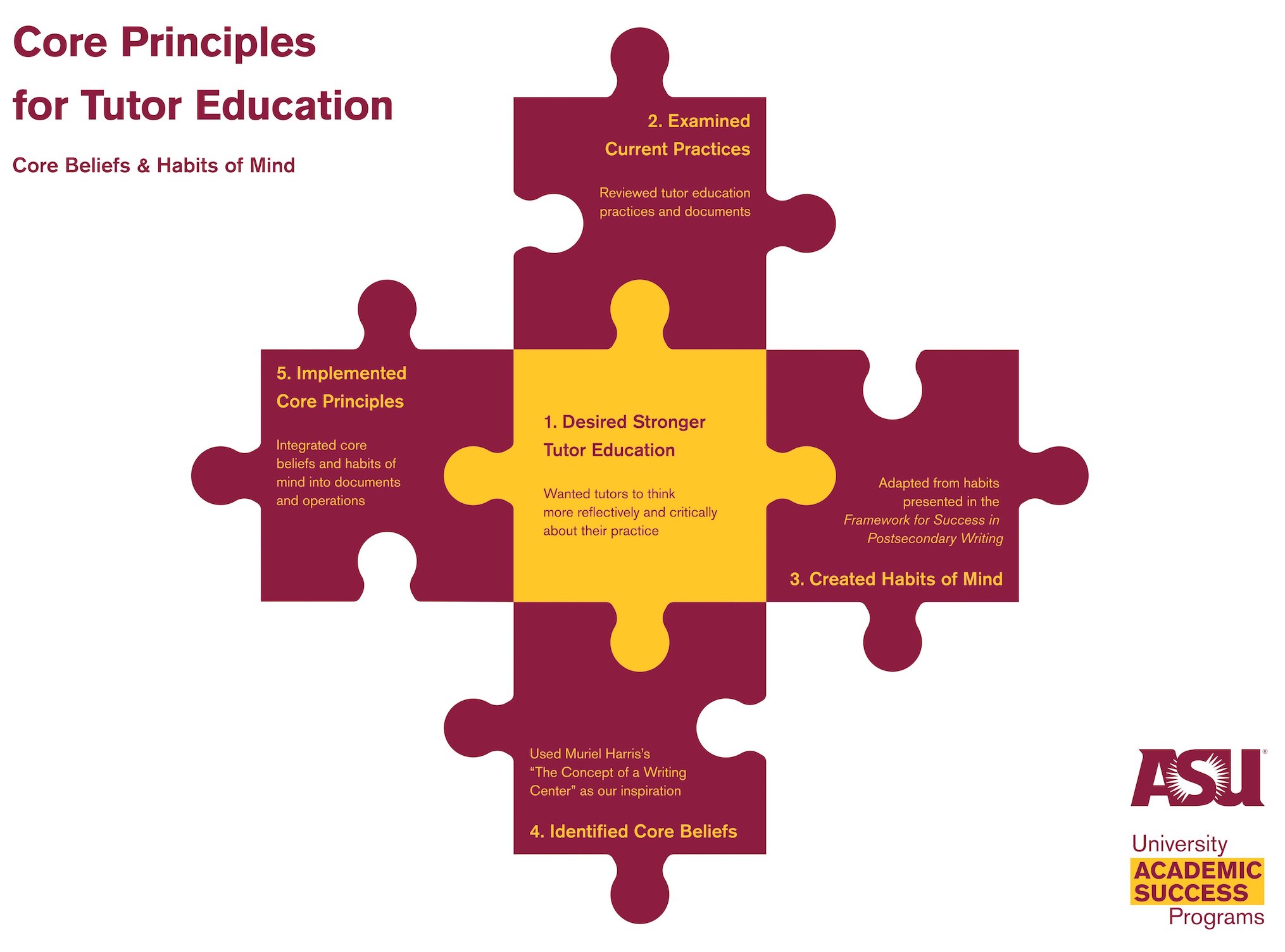

Our team underwent the process of revising our ongoing tutor education practices, including initial training sessions, bi-weekly education meetings, and tutor observations and evaluations. In doing so, we discovered that grounding our practices in principles derived from carefully selected scholarship was a successful approach, both for meeting our goals and for professionally developing our peer writing tutors. Our centers' core principles consist of a set of tutor habits of mind as well as beliefs about the philosophy and practice of writing center work. Based on our positive experience, we argue for the value of writing center administrators engaging in their own processes to develop a set of core principles and embedding these principles into tutor evaluation and ongoing education. This chapter provides an account of the two processes we used to develop and implement our core principles as shown in Figure 1 below.

|

| Figure 1. ASU-University Academic Success Programs' core principles for tutor education. This figure represents our process. Graphic design by Kara Van Zile. |

We will first review how we developed our habits of mind and then how we developed our beliefs. As we describe our processes, we will share materials that we utilize in our day-to-day practice and will also include links, embedded documents, and quotations from tutor interviews (referenced using pseudonyms in a study that was approved by our Institutional Review Board) to illustrate the impact of our core principles on tutors. Our hope is that sharing these materials will make clear how we operationalized the principles we chose and will also serve as examples for other administrators who want to create or revise and then integrate their own set of principles into their centers. Even if an administrator is not certain about taking all of the steps we used, these materials may give insight into the types of documents that can help inform writing tutor education.

Our Terminology

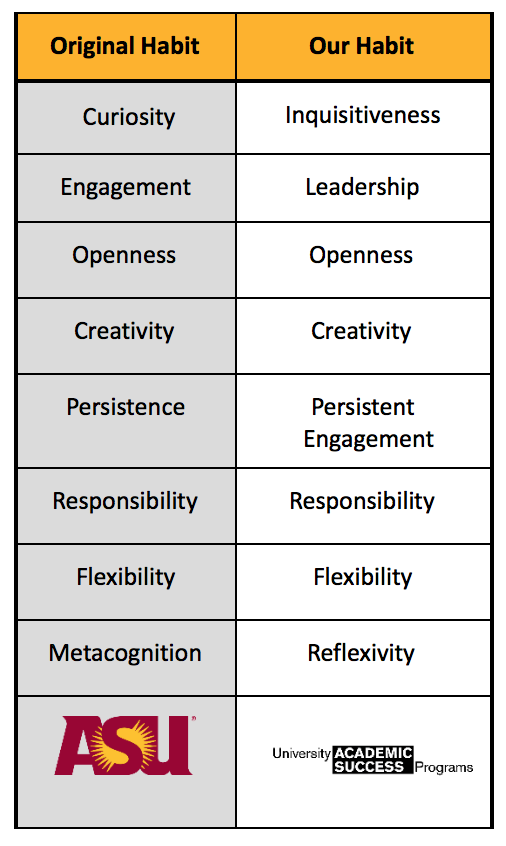

Our team developed our habits of mind from those described in The Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing, a document written by representatives from The Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA), the National Council of Teachers of English, and the National Writing Project. We slightly revised these habits to enable us to describe for our tutors the qualities, mindsets, and behaviors we expect them to demonstrate in their work. Complementing our habits of mind are our beliefs, adapted from Muriel Harris's "The Concept of a Writing Center." Our beliefs refer to the foundational pedagogical guidelines that inform our writing center practices. In other words, the habits of mind refer to the qualities and behaviors we desire of our tutors, whereas beliefs refer to the philosophical concepts central to the field of writing centers. Together, our habits of mind and beliefs guide our programmatic decisions and engage tutors in ongoing education. Descriptions of how we developed our habits of mind and integrated them into tutor education as well as examples of how tutors engaged with our beliefs are detailed below.

Our Habits of Mind: Desired Writing Tutor Qualities and Behaviors

|

| Figure 2. Habits of mind comparison from ASU-University Academic Success Programs. This figure demonstrates the way in which we changed the language from the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing (CWPA et al.). |

Our first step in improving our tutor education was finding a way to make more visible, quantifiable, and transparent the qualities and behaviors we expect tutors to demonstrate in their work. We chose the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing because of its identification of eight habits of mind expected of successful writers. Our writing tutors' primary responsibility is engaging students in conversations about writing projects and processes; therefore, we were drawn to the Framework's descriptions of "ways of approaching learning that are both intellectual and practical and that will support students' success in a variety of fields and disciplines" (CWPA et al. 1). We believed that drawing from the Framework's habits of mind could help our tutors better understand the nuances of the demands faced by college-level writers. Furthermore, we wanted these habits to provide our tutors with language for thinking more critically about their work performance in terms of the questions they use to engage writers, the types of resources they share, and the suggestions they offer.

As a result, we reviewed the habits of mind and made revisions appropriate for the context of peer writing tutoring. Our revisions included changing the names of some habits while keeping others. For example, we re-named the Framework's habit "curiosity" as "inquisitiveness" to encourage tutors to be more intentional about contributing to their campus writing center community. Re-casting the Framework's habit "engagement" as "leadership" allowed us to highlight the contributions that tutors can make through the writing center. In Figure 2, we include the list of the original habits from the Framework along with our revisions.

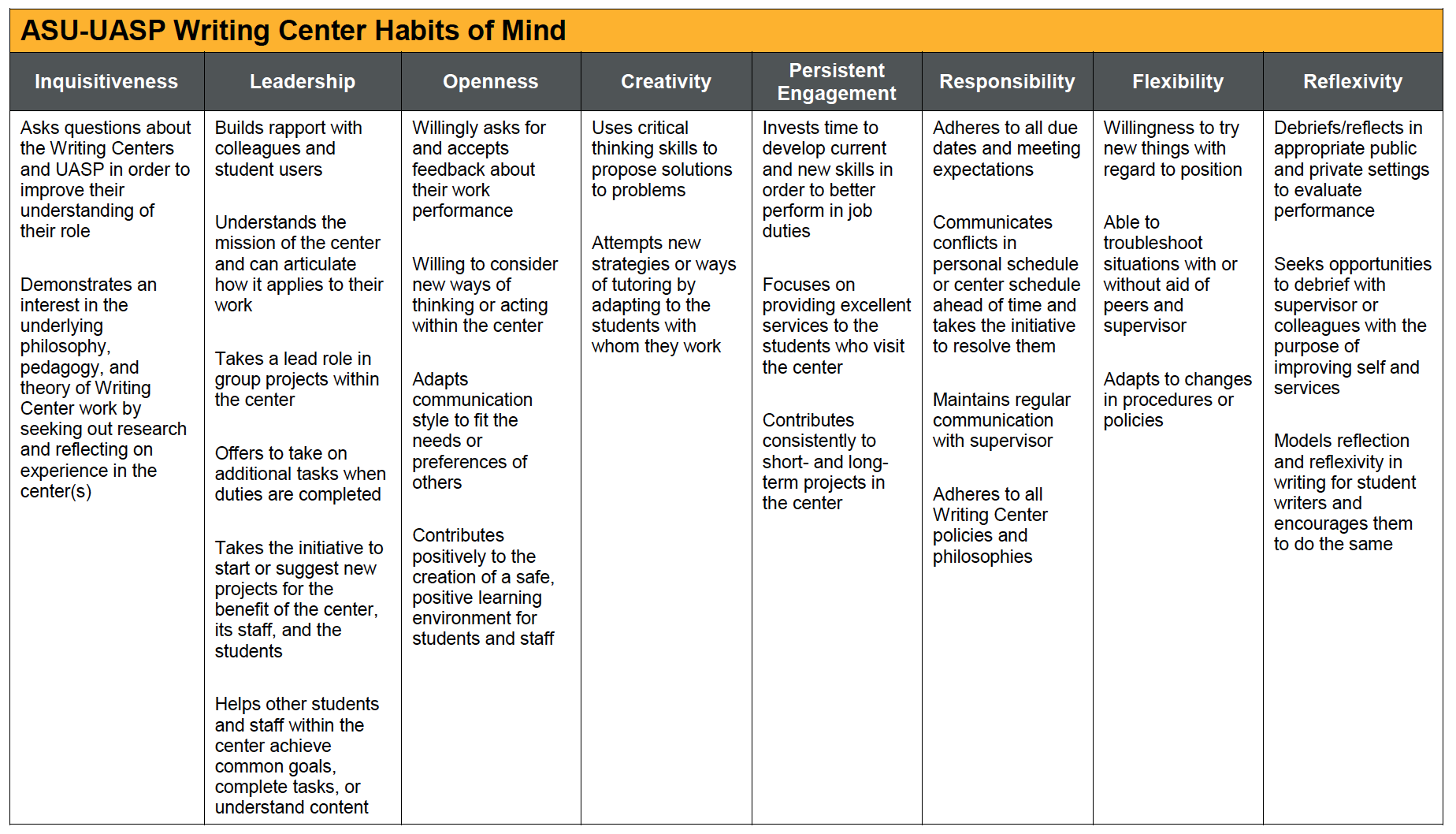

In addition to revising the titles for the habits, we also rewrote the descriptions to better fit our context. For example, the Framework describes flexibility as "the ability to adapt to situations, expectations, or demands" (1); however, we rewrote the description to reflect the importance of tutors adapting to changes in procedures and policies. Our descriptions included multiple points for each habit that outline the behaviors we wanted to see our tutors demonstrate. We compiled these descriptions into one document that we share with our tutors, and this document is shown below in Figure 3.

|

| Figure 3. ASU-University Academic Success Programs' writing center habits of mind. This is the document we use to inform our practices. |

After finalizing our habits of mind and their descriptions, we then looked for ways to provide tutors with multiple opportunities to assess their development. Our goal for integrating the habits of mind into important onboarding documents, such as new tutor observation forms, was to transition newly hired tutors into the culture of our writing centers. New tutors have always observed current tutors during their first week of work. The observation forms now include a question that asks them to look for evidence of how current tutors apply the habits of mind in sessions with writers. After successfully integrating the habits of mind into these onboarding processes, we then focused on adding the habits into tutor evaluations and ongoing tutor education to help tutors regularly identify and apply these habits to their work, find examples from their tutoring sessions to discuss with their supervisors and peers, and articulate the value of demonstrating these habits in their academic, personal, and professional lives. For example, during initial tutor education workshops, tutors are introduced to the habits through reflective writing and group activities that ask them to describe their own beliefs and philosophies about writing tutoring. Using that information, they brainstorm tutoring strategies to illustrate each habit of mind. This process mirrors Tom Earles and Leigh Ryan's approach to developing codes of professionalism, whereby tutors are encouraged to brainstorm specific workplace behaviors that fall within categories such as "responsibility" and "respect."

In our initial tutor education workshops, habits identified by tutors or by our team as needing attention serve as the basis for ongoing tutor education workshops. For instance, a workshop based on persistent engagement and inquisitiveness includes discussions and activities focused on helping tutors be more intentional about role modeling and how to use resources in sessions as a way of fostering students' independence. A quiz has been used as an interactive activity to get tutors accustomed to finding information in our center handouts. After tutors complete the quiz, they engage in a conversation about how to model using informational handouts during tutoring sessions. Throughout these activities, tutors are prompted to identify their own current strengths and areas for development with regard to writing and writing tutoring. Areas for development often turn into annual goals that tutors revisit and revise throughout the academic year. In an interview with Ava about her experiences as a new tutor, she identified how the habits of mind were connected to her annual goals:

I think about the habits of mind every shift. I made that a goal when I first started, to think of them every day, and I actually used to keep my binder with me and I would reference them...eventually, it just became part of my cycle. . . . it feels natural, and when I do my daily reflection at the end of my shift, I can really think about how I was doing with our tutoring cycle, with our habits of mind, and then with my personal goals that we set at the beginning of the semester.

Additionally, when completing the Writing Tutor Self-Evaluation Form, tutors use the habits to reflect on their performance throughout the year. This evaluation form asks tutors to provide examples of the habits they identify as their strengths as well as areas in which they need to develop. During evaluation meetings, our team found that tutors were able to identify patterns in their work and could then make plans of action for continued growth. One tutor in particular, Gloria, illustrated how she uses the habit of openness to help her better connect with students by using her own experience to help personalize a session: "Openness is important because you have to establish a connection with a student. . . . I do that all the time when I am working with students who are having trouble with organization in their essays. I talk to them about how I like to write an outline to keep myself on track." As tutors think critically about their work performance and identify specific ways that they demonstrate the habits of mind, those moments are useful learning experiences for both supervisors and tutors. Likewise, another tutor, Ava, highlighted the ways that the habits of mind in the self-evaluation prompted her to think critically about her strengths and areas for development:

The habits of mind make me feel like I'm a better tutor than I give myself credit for sometimes. I often forget about a lot of the skills that I have as a tutor and educator, and it's nice to be able to really force myself to think about my strengths and my weaknesses in all these areas. I like to define how I do a habit of mind, but then also provide examples, and I notice that if I can't provide a lot of examples in an area, then that's an area that I should refine.

Ava addresses a common experience for tutors. Many tutors are often too general (e.g., focusing on abstract qualities and behaviors) or too specific (e.g., focusing on specific experiences without going "big picture"). Incorporating the habits of mind into the Writing Tutor Self-Evaluation Form prompts our tutors to find connections between specific experiences and the qualities and behaviors we desire of them. Self-evaluation forms are just one tool, along with other materials (such as quizzes, observation forms, and workshops), that both tutors and administrators can utilize as a means of applying tutor education concepts. We see our habits of mind acting as a framework to guide decisions about tutor education materials and practices, similar to Julia Bleakney's smart practices derived from interviews with writing center directors.

Seeing our tutors engage with and personalize our habits of mind, as exemplified in this quote from Gloria, confirmed the value of our decision to find new ways of connecting tutors' work to desired qualities and behaviors: "In other employment that I've had . . . you never really have an opportunity to really look back on your experiences in a structured way. And so, I feel like having the definition and I guess the separation of the eight habits of mind has really helped me kind of separate my job duties and better understand the areas that I can improve." This exemplifies a tutor possessing the tools to look back on their own work and derive meaning from their experience, thus becoming a more self-regulated learner. In the chapter "The Mindful Tutor," Jared Featherstone et al. discuss Barry Zimmerman's 2002 scholarship on self-regulated learners engaging in self-monitoring, setting appropriate goals, and developing effective strategies. Since implementing our habits of mind, we have continually observed evidence of these behaviors in our tutors. While we were seeing results at this stage, our next step was to make the ways in which our habits were grounded in writing center scholarship transparent to our tutors.

Our Beliefs: Writing Center Philosophical Concepts

Seeing tutors use the habits of mind to think reflectively and critically about their experiences inspired us to develop a set of beliefs about the philosophy and practice of writing center work. Therefore, our next step included creating a set of writing center beliefs to complement our habits of mind that would more closely connect tutors' qualities and behaviors to the tacit beliefs guiding our administrative and pedagogical decisions. To form our beliefs, we reviewed scholarship about foundational concepts in writing and writing center work, and we noticed that several of these texts were recently published. This told us that developing a set of beliefs for writing center programs was a timely pursuit and inspired us to distill beliefs from our readings and experiences. These texts included volumes used for tutor education, such as Leigh Ryan and Lisa Zimmerelli's The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors and Lauren Fitzgerald and Melissa Ianetta's The Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors, which both acknowledge an increasingly diverse landscape of writing centers in the United States and thus discuss a range of guiding concepts for writing tutors. Further, Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle's influential collection of essays about writing, Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, uses the term threshold concepts to identify and describe concepts "critical for continued learning and participation in an area or within a community of practice" (2). Rebecca Nowacek and Bradley Hughes's essay in Naming What We Know provides a rationale for how foundational concepts "cannot only help writing center coordinators articulate (and therefore clarify and sometimes revise) priorities for the structure of tutor education programs, [but they] can also help tutors themselves conceptualize their own work with writers and with faculty" (171). Nowacek and Hughes conclude by inviting readers to identify and define additional concepts related to writing centers. Inspired by this collection of scholarly work, we saw value in articulating a set of beliefs to guide our writing center work.

|

| Figure 4. ASU-University Academic Success Programs' writing center mission statement. This image is on display in each center across our four physical campuses. Graphic design by Amy Cheung. |

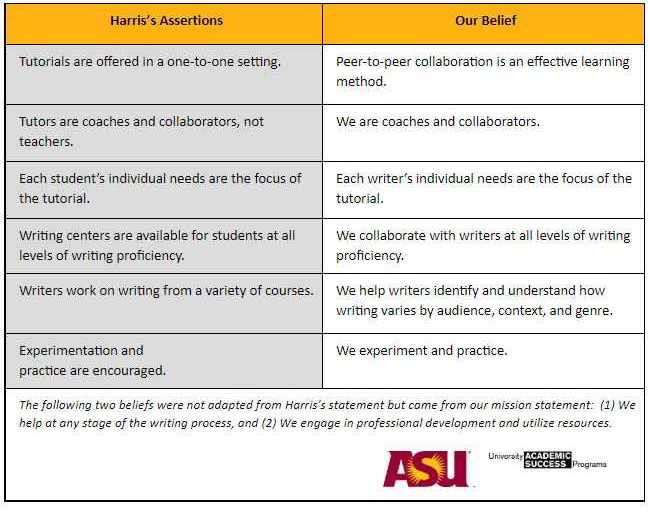

When we began developing our beliefs, we wanted to draw from concepts considered central to the writing center field. Muriel Harris's assertions described in the "SLATE (Support for the Learning and Teaching of English) Statement: The Concept of a Writing Center" are certainly foundational as evidenced by the International Writing Centers Association's recommendation that readers consult them when looking for information about starting a writing center. We also wanted our beliefs to engage tutors in conversations about the transferability of skills developed through peer tutoring, a realization that we believed, like Bradley Hughes, Paula Gillespie, and Harvey Kail in "What They Take with Them: Findings from the Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project," would stay relevant to tutors' lives beyond writing centers. Given Harris's inclusive language and connections between writing centers and other contexts, her "Statement" suited our purposes well. However, to better reflect our writing center program, we revised some of Harris's language and also incorporated our writing center mission statement which appears in Figure 4 below.

For example, our belief that "peer-to-peer collaboration is an effective learning method" is inspired by Harris's principle that "tutorials are offered in a one-to-one setting" (Heading 2). We slightly shifted the language from "one-to-one tutorial" to "peer-to-peer collaboration" to highlight that our tutors should study how to collaborate with peers. In developing our other beliefs, we used a similar process of shifting the language to reflect our program's complete set of writing center beliefs. Figure 5 lists our Writing Center Beliefs and highlights how we were inspired by Harris's statement.

|

| Figure 5. Comparison of Harris's assertions and the ASU-University Academic Success Programs' writing center beliefs. |

We hoped that developing and then sharing our beliefs with tutors would encourage them to think more critically about their daily practice. With that goal in mind, we strategically implemented these concepts into our tutor education practices. Since implementation, we have been impressed with tutors' engagement with the concepts in ongoing education sessions and evaluation meetings. For example, in their observation of another tutor, Sam wrote: "When her students are stuck on something . . . she offers a plethora of options a student might employ to get them thinking and often couples this with an explanation of which option might be the most effective given the particular rhetorical situation." Sam has not only learned our belief that "we help writers identify and understand how writing varies by audience, context, and genre" but was also able to identify this belief in action and provide evidence about how a fellow tutor's practices illustrated this belief.

Our beliefs had another desirable, albeit unexpected, outcome: they helped guide tutors through unfamiliar or challenging tutoring situations. Tutors have often told us that when they were unsure what to say in tutoring sessions, they thought of a belief, and this helped them decide how to proceed. The intentional use of these beliefs in our centers helps ground the tutors in their day-to-day work while also providing them with a way to strategically think about how they can grow in their roles. In an evaluation meeting, for example, Ava shared the story of a student who left the tutoring session several times to receive phone calls, which prevented them from addressing the multiple tasks on their agenda. Ava reminded herself that "each writer's individual needs are the focus of the tutorial," so she decided to explicitly ask the student about his needs. The student shared that he needed to end the session early, so Ava helped him revise the session agenda so they could focus on the most important task before the session ended. Thus, beliefs can provide parameters within which tutors learn how to react to challenging tutoring situations.

Finally, we credit the creation and implementation of these beliefs with providing a shared language to talk about writing and writing tutoring and for engaging tutors in conversations about transferability in training sessions and beyond. Tutors often pull language from the beliefs when explaining our philosophies to students, staff, and faculty. Ava elaborates: "When I'm advocating for our center, and people ask 'What does the Writing Center do?,' I think we make this so clear not only in training, but also in the way that we function as a workspace. . .the beliefs feel like what we do and they're not things that we memorize." One way we have observed tutors integrating these beliefs into their daily work is through the use of documents such as weekly reports. While the weekly report questions ask them to reflect specifically about the habits of mind, we often see tutors infusing the core beliefs into their responses. For example, Payton reflected:

I've definitely noticed that students were more stressed out lately, whether they came into the walk-in room really anxious, or weren't feeling confident in their writing. I had one student in particular who went on a small rant about how their paper was garbage, and [how] they should probably just start over. Instead of cutting them off or dismissing their concerns, I just let them vent until they'd calmed down a bit, and then tried to be supportive and reframe the revisions they needed to do as something to add to what they already had, rather than replacing or undoing anything they'd worked on. By the end of the session they seemed happy with what we'd worked out, but I think giving them that space and time to get their frustration out helped the session be more productive afterwards. I think my response to that situation would fall best under reflexivity and openness (both in encouraging the student to practice those, and with myself trying to understand the student's frustrations).

Payton both identifies how the habits of mind were applied in this tutoring session and demonstrates an understanding of student-centered pedagogy by highlighting benefits of peer-to-peer learning. Tutors in our centers now apply concepts like student-centered pedagogy and peer-to-peer learning and use words like audience and coach in other written reflections with ease. Additionally, when our tutors read writing center scholarship or attend conferences, they continue to see these words and phrases; thus, this language extends beyond our centers, connecting our tutors to the larger writing center community.

Suggestions for Further Research

There are many benefits to developing and integrating a set of program-specific core principles, and opportunities to continue additional research are abundant. Like Mary Pigliacelli, who used Practitioner Action Research (PAR) to improve her own pedagogy and to then help tutors develop habits of mind, we set out to better articulate our expectations to our peer writing tutors and ended up furthering our understanding of writing center pedagogy and tutor education practices. In this way, we discovered that the creation of core principles can be an exploratory exercise for a program, functioning "as an exigence, an opportunity to uncover and interrogate assumptions" (Yancey xix). Writing center teams hoping to explore assumptions, improve pedagogy, and ultimately develop a set of core principles would benefit immensely from further research on how individuals collaborate on teams to accomplish these goals.

Our collaborative process was often messy, challenging, and inspiring. One of the reasons why the process was challenging is that our team of writing center administrators supervise multiple writing centers across various locations and contexts. When developing our core principles, we wanted a set of values and beliefs that could be applied to these centers and ultimately unify them. Several authors in this volume discuss their processes for creating tutor education standards for large groups of tutors, some of whom work remotely, tutor in different centers, or are supervised by different administrators (see Daniel Gallagher and Aimee Maxfield and Sarah Peterson Pittock and Erica Cirillo-McCarthy), and we find this work incredibly valuable. Further research on the process and implications of developing a shared set of core principles for tutors and administrators who work across different locations and contexts would likely be a fruitful endeavor.

When using core principles throughout our various writing center locations, we observed tutors reflecting upon their work meaningfully and developing in ways that would last beyond their tenure as writing tutors. For example, our tutor Rebecca mentioned:

. . . the beliefs and the habits of mind have really helped me know how to deal with different people and different situations and how to handle people from all walks of life and like how they learn and how they talk and how to communicate. And it's taught me how to ask for help in different situations where I don't understand something. And it's made me think more outside the box. . . and I think it just teaches you how to handle yourself in multiple situations . . .

It is promising to see how tutors are applying our core principles to other contexts, and further research on tutors and tutor alumni, including replications of the Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project, would illuminate how tutors are applying writing center core principles in other educational and professional contexts. This data would be valuable not only internally but also externally as writing centers communicate the impact of their programs with stakeholders.

Conclusions

By deciding to embed core principles into multiple materials, administrators could find new ways to inform their centers' education practices by uncovering implicitly held beliefs and values, putting those beliefs and values into explicit language, sharing that information with others, and creating or revising new items. Like Earles and Ryan's codes of professionalism, we believe that our core principles are living documents that must be revisited and reviewed regularly, and we will likewise continue to examine, expand, and revise our materials.

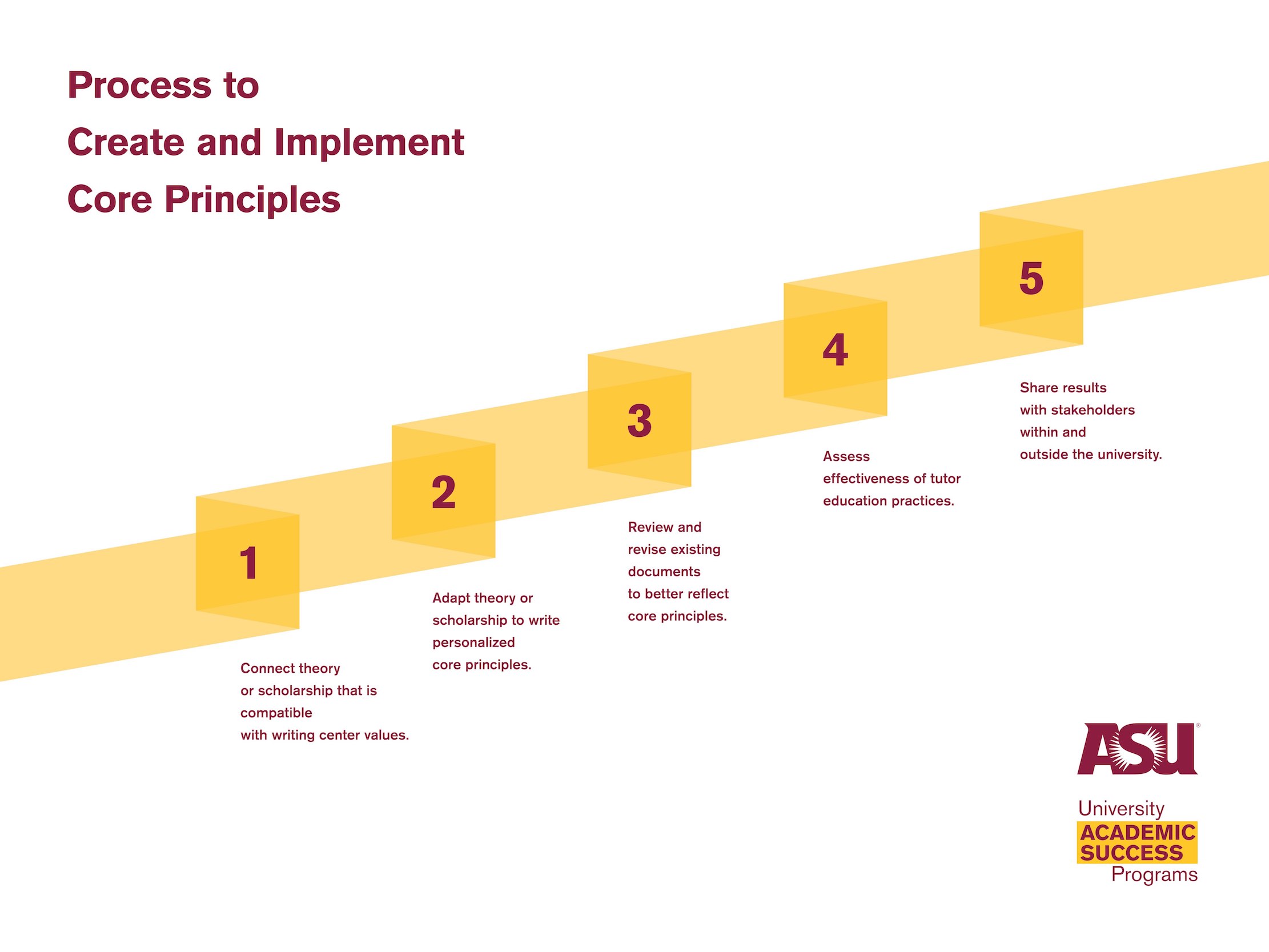

In sharing our processes, materials, and tutor perspectives, our goal is not to propose a one-size-fits-all approach but rather to emphasize that there is value in undertaking the development of a set of core principles that meets the unique needs and goals of a writing center. For centers that might want to begin or continue a similar process, we offer considerations for identifying and eventually integrating a set of program-specific core principles as outlined in Figure 6.

|

| Figure 6. Process to create and implement core principles. This flowchart shows the steps we took to fully incorporate our core principles into our in-person and online writing centers at ASU-University Academic Success Programs. Graphic design by Kara Van Zile. |

These suggested steps are meant to guide writing center administrators in designing a process for exploring and developing core principles that are representative of their writing centers. Once core principles have been incorporated, administrators will be able to assess the effectiveness of their tutor education practices and share those results with stakeholders within and outside the university. The process of developing and integrating a set of program-specific core principles is an investment that can help administrators make significant and lasting improvements to their tutor education programs. It will challenge administrators to be more explicit about their goals for tutor education and provide them with a framework for program assessment while simultaneously challenging tutors to develop, demonstrate, and articulate the skills, mindsets, and behaviors valuable in their writing center work and in other contexts.

Works Cited

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth Wardle. Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies. Utah State UP, 2015.

Bleakney, Julia. "Ongoing Writing Tutor Education: Models and Practices." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Bleakney.html.

Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and National Writing Project. Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing. CWPA, NCTE, and NWP, 2011, wpacouncil.org/files/framework-for-success-postsecondary-writing.pdf.

Earles, Tom, and Leigh Ryan. "Teaching, Learning, and Practicing Professionalism in the Writing Center." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/EarlesRyan.html.

Featherstone, Jared, et al. "The Mindful Tutor." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Featherstoneetal.html.

Fitzgerald, Lauren, and Melissa Ianetta. The Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors: Practice and Research, Oxford UP, 2016.

Gallagher, Daniel, and Aimee Maxfield. "Learning Online to Tutor Online." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/GallagherMaxfield.html.

Harris, Muriel. "SLATE (Support for the Learning and Teaching of English) Statement: The Concept of a Writing Center." International Writing Centers Association, http://writingcenters.org/writing-center-concept-by-muriel-harris/. Accessed 14 February 2017.

Hughes, Bradley, et al. "What They Take with Them: Findings from the Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project." The Writing Center Journal vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 12-46.

Johnson, Karen G., and Ted Roggenbuck, editors. How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection. 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/JohnsonRoggenbuck.html.

Kail, Harvey, et al. The Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project.

https://writing.wisc.edu/pwtarp/. University of Wisconsin-Madison. Accessed 30 May 2018.

Pigliacelli, Mary. "Practitioner Action Research on Writing Center Tutor Education: Critical Discourse Analysis of Reflections on Video-recorded Sessions." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Pigliacelli.

Pittock, Sarah Peterson, and Erica Cirillo-McCarthy. "Let's Meet in the Lounge: Cross Tutor Training in a Writing and Speaking Center." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/PittockCarillo-McCarthy.html.

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. 6th ed. Bedford/St. Martins, 2016.

Nowacek, Rebecca S., and Bradley Hughes. "Threshold Concepts in the Writing Center: Scaffolding the Development of Tutor Expertise." Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State UP, 2015, pp. 171-85.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. "Introduction: Coming to Terms: Composition/Rhetoric, Threshold Concepts, and a Disciplinary Core." Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State UP, 2015, pp. xvii-xxxi.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank our director, Ivette Chavez, in University Academic Success Programs (UASP) for supporting us as we collaborated to write our article. We would also like to thank our colleagues Amy Chung and Kara Van Zile for their graphic arts contributions. Additionally, we thank our colleague Adam Ferguson for helping us to revise and redesign two of our key figures and for dedicating his time to providing that help. And, of course, we want to thank our tutors for their willingness to share their evaluation materials with us for this article and for all of the ways that they support and work with students in our UASP writing centers at Arizona State University.

BIOS

Dr. Lisa Cahill is an associate director in University Academic Success Programs (UASP) at Arizona State University where she oversees the undergraduate and graduate writing centers at ASU's four campuses and online. In addition, she oversees UASP's online subject area tutoring program as well as UASP's graduate initiatives and community partnerships to build tutoring programs. Her research interests include writing in the disciplines, writing centers, writing instruction, writing groups, and graduate education.

Molly Rentscher was the coordinator of University Academic Success Programs' West Campus Writing Center and Graduate Writing Center at Arizona State University. She is now the coordinator for graduate writing support at University of the Pacific. Her research interests include writing center pedagogy and writing program administration, and she is currently working on several projects related to linguistic diversity and multilingual writing in writing centers.

Kelly Chase is the coordinator of University Academic Success Program's Polytechnic Campus Writing Center at Arizona State University. She holds an M.F.A. in Creative Writing-Fiction and an M.A. in English from McNeese State University in Lake Charles, Louisiana. She is a New York transplant and loves the arts.

Darby Simpson is the coordinator of University Academic Success Program's Tempe Campus Writing Center and Graduate Academic Support Center at Arizona State University. She is also a doctoral student in ASU's English Education program and is a former high school English teacher. Her current research interests include how writing center strategies can be utilized by students and by teachers in K-12 classrooms.

Jessica Jones is Coordinator of the Online Writing Center, Online Graduate Writing Center, and Online Subject Tutoring Center in University Academic Success Programs at Arizona State University. As a Higher Education professional with twelve years of experience, she considers herself a life-long learner and loves the opportunity to research and learn new information about how to improve personal skills and impact the success of others.