CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Our Professional Descendants:

Preparing Graduate Writing Consultants

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Katrina Bell

Colorado College

|

| Photo credit: Luc MacArthur |

As a new director, there's nothing I value more than my past experiences in writing center work. Truly, nothing could have prepared me for the myriad responsibilities of directorship like my past collaborations with my director as an undergraduate consultant and as a graduate consultant and administrator. Through my undergraduate institution, I participated in a full-semester course in writing center theory and practice that required 30 hours of observation/shadowing, along with reflections and research papers. I collaborated with the director to present research at the Midwest Writing Center Association, as my first exposure to professional conferences. As a high school teacher, my work with the Writing Center informed my interactions with students and scaffolding of assignments more than did most of the education theory classes I had taken. The big-ideas-to-sentence level model of writing center work helped me show students how to prioritize; my readings on appropriation, the academy, and student voice informed my own feedback priorities. When I sought a Ph.D., I was fortunate enough to have not only an additional graduate level course in writing center theory and practice, but full courses in writing center directing and writing program administration. As a graduate student, I requested placement in the writing center as a way to fulfill my assistantship, but many other graduate students were assigned to the center, which was their second or third choice for assistantship placement, and few had the opportunity for formal training beyond a pre-semester workshop and weekly meetings. Though I self-selected coursework in writing center theory and administration, my graduate program did not provide a cohesive way to prepare all graduate assistants for writing center work. As I saw the variability in professional development and training within my own graduate program, I was left wondering what models for consultant education looked like at other institutions, and how those models prepare graduate consultants for work in and beyond the graduate writing center. Without the graduate experience I gained as a consultant and graduate assistant director, in combination with the courses I took, I don't think that I would have been able to move as easily into full-time writing center administration as I have. And yet, despite my 20-year history in and out of writing centers, I still feel unprepared for some of the political negotiations and climates at my current institution.

My initial curiosity and present need for information about consultant preparation is not unique. Questions about training manuals, modules, and curriculum pop up frequently in WCenter listserv discussions, and subscribers consistently respond with advice that targets secondary, undergraduate, and graduate training. A response to Jessica Langan-Peck's 2015 request for help in constructing a tutoring manual for secondary schools suggests the Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors as a start, as well as a few secondary-specific texts. Zachery Koppelmann's more recent request seeks assistance in creating a "crash course" to prepare undergraduate tutors for an upcoming semester. However, none of the advice includes a manual for preparing graduate writing tutors, which may be because there are no commercially published guides. Ben Rafoth's A Tutor's Guide: Helping Writers One to One includes a chapter dedicated to graduate writing as a genre, but the other available manuals and guides barely address graduate writers as a population, and they certainly don't address graduate writing consultants.

For the purposes of this discussion, I define professional development (PD) as writing center education that includes the discussions, activities, and texts that help not only to meet current institutional and individual needs, but also to move participants toward their professional goals. Graduate students' experiences with PD may include administrative tasks, a collaboratively determined PD agenda, and an engagement with the tensions between writing center faculty/staff and the academy. Graduate students may also be challenged to address genre and disciplinary issues particular to thesis or dissertation projects, to create workshop agendas for classroom outreach, or to justify pedagogical choices within the teaching of writing. Beyond their work in writing centers, graduate PD may also engage the realities of writing center careers, the transfer of experience beyond the walls of the writing center, or roles for allies/advocates within and outside of the writing center.

Through both a survey and an analysis of supporting curricular artifacts, I conducted a study to find out how graduate writing consultants are engaged in writing center PD. Survey results indicate that, while much good is happening within writing center PD programs for graduate students, there isn't much evidence in this sample that writing center administrators are deliberately preparing them as our "professional descendants," a term used by Michael A. Pemberton and Joyce Kinkead to describe new cohorts of writing center administrators and theorists (9). Graduate student consultants and administrators are a unique group that we must intentionally engage in discussions of how the skills beyond one-to-one writing instruction transfer to faculty and administrative positions in higher education and to careers outside of the academy. In this chapter, I discuss emergent trends revealed from my data in graduate writing consultant education, training, and PD. I also make suggestions as to how to further strengthen PD for those graduate consultants who are considering careers in writing center work and conclude that through an intentional structuring of the graduate writing center experience, including the articulation of goals for PD, writing center directors can provide additional opportunities for individual graduate students to grow professionally.

Literature Review

As I began researching this complex topic, I found little information about graduate professional development for writing center consultants, and in much of the literature in the field of Writing Center Studies, the term commonly used is "tutor training." I don't believe, though, that training encompasses the depth of the work that we do in writing centers; Brad Hughes refers, instead, to "ongoing education" ("The Tutoring Corona"). Training, in many senses, focuses on a specific skill to accomplish a given task, while PD, or ongoing education, indicates a more flexible approach that impacts the person and the career through a wider variety of activities that may include training but will most likely move beyond skill development. PD may include discrete skill acquisition but should also intentionally help participants connect those skills to their professional goals.

My current institution, a small liberal arts college with few graduate students, offers undergraduate consultants a short nine-day intensive class followed by a semester—long, once-weekly course, both of which are credit-bearing and focus on a combination of theory and practice. Texts and topics include those developed primarily for undergraduates to acquaint students with the history of writing centers, the major theories grounding the work, and the basic strategies for approaching student writers, such as Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors, Longman Guide to Peer Tutoring, A Tutor's Guide: Helping Writers One-to-One, and ESL Writers: A Guide for Writing Center Tutors. These texts can acquaint all consultants (undergraduate, graduate, and professional) with the writing process, session protocols, and strategies for working with specific populations. While we may use these texts to ground coursework, they often focus on tasks specific to writing center work, rather than disciplinary conventions, tensions within the academy for professionals, or the role writing consultations may play in consultant careers.

For graduate student consultants, professional development may look similar in the texts that ground the work and often also reflects a generalist approach. However, while there are abundant resources for undergraduate PD, there are few resources for those who are seeking models for graduate writing consultant PD. Writing Centers in Context, published 25 years ago, offers two case studies, one from the Purdue Writing Lab, penned by Muriel Harris, and one from the University of Southern California, by Irene Clark. These studies, which provide snapshots of two established writing centers that employ both graduate and undergraduate consultants, can provide outlines of education programs that are institution specific, but may not provide models that work outside of those spaces. However, the model presented by Christopher LeCluyse and Sue Mendelsohn, which uses a combination of rhetorical concepts to focus on the needs of those consultants as a specific audience, may be more adaptable. They suggest assessing the rhetorical situation and then employing topoi (topic-based discussions) to meet both the needs of the consultants and their clients in the writing center context (104). To come to this conclusion, LeCluyse and Mendelsohn recognized the weakness of their originally front-loaded training, which "unwittingly sent the message that writing consulting is like riding a bicycle, a skill acquired once and quickly mastered rather than a discipline one must engage with continually" (110). In addressing these messages, they coordinated the weekly topoi-based workshops, allowing consultants to select topics meaningful to their own work in writing centers, and encouraging graduate consultants to present the information to their peers. The collaborative nature of the workshops, they argue, empowers graduate consultants to train their peers through leading topoi, engaging peers in conversation without a strict hierarchy. To allow for greater access and flexibility, administrators film the topoi to make each workshop available digitally and asynchronously. This model seems particularly appropriate for busy graduate consultants who may not have the opportunity to participate in full-semester classes. However, online modules or videos are not necessarily as purposeful as PD that incorporates mentoring, goal setting, interactive discussions, or reflection, though these components can certainly be built into the online formats with some intentionality and director follow-ups.

Coursework in writing center studies or writing program administration may move closer to a working definition of PD than either skill-based training sessions or online modules, though not all graduate consultants have the opportunity to take them. Jackson, et al.'s study of graduate level writing center class syllabi found that "courses are theoretically and practically grounded, emphasizing the shifting, often contested, theoretical and practical frameworks that have shaped and continue to shape writing center work" (140). The requirements for the courses vary, but they are "designed to encourage students to think and act like writing center professionals," by challenging graduate writing consultants to complete research projects, proposals, bibliographies, book reviews, exams, and discussions, and to bring their own writing to their centers (141). However, while these courses teach graduate students how to be scholars, they neglect instruction on how to be professionals in the field and how to balance the demands of the daily and emotional labor involved in writing center work. Their analysis concludes with a call for the further professionalization of writing center work, which will prepare graduate consultants to carry on that work once they complete their degree programs. This professionalization of writing center work requires intentional structuring of development opportunities for graduate consultants and administrators, though the authors stop short of discussing how we can offer those experiences to graduate consultants beyond coursework.

One way to envision PD offerings beyond coursework would be to redefine graduate writing center work as an internship, and to include participation in directorial work, including reflective practice, creating and realizing a research agenda, or developing and analyzing writing center assessments. Natalie Singh-Corcoran explains that graduate students "in writing center administrative positions receive practical/hands-on experience, but because they are not usually given opportunities to reflect on their practices as assistant directors, the positions themselves perpetuate the idea that a directing position is strictly managerial" (33). To remedy this potential issue, directors can engage graduate consultants in the training of other consultants and in writing center research to help those graduate consultants to see themselves as professionals. LeCluyse and Mendelsohn call this process an "initiation into a field of academic discourse and practice" (106). A graduate level initiation to writing center work as both a profession and a field of study may help potential directors to understand the nuances of the job market and ease the transition from graduate student to writing center professional.

Much of the discussion I have highlighted is ten to fifteen years old. In general, we know little about the way that PD works at higher education institutions for either graduate consultants or for current administrators. This also means that we know very little about the ways that current writing center professionals have become prepared for their positions; much of the information we have is anecdotal, narratives of individual paths to writing center work, rather than a cohesive documenting of the myriad paths we have created to bring our graduate consultants into the field. Without a more systematic investigation of the models available for graduate writing consultants or administrators' PD, we can only advance as individuals, rather than as a field. My study attempts to fill this gap in the research. I wanted to know:

- How do we prepare graduate students for their work in writing centers during their time as graduate students?

- What are we doing to foster the newest generations of writing center professionals?

Methodology

To answer my question of how other graduate consultants and administrators are prepared for their work in and beyond writing centers, I sent a survey (see Appendix A) through the WCenter listserv asking writing center administrators (directors, coordinators, and sub-directors/coordinators) to describe the key topics, texts, and activities they employ when training graduate writing center consultants. No questions requested specific institutional or director demographics. Rather, the questions were designed to collect general program characteristics, such as clientele, the College Reading and Learning Association's certification, timing of the PD activities, compensation, and administrative duties within the writing center. Questions about topics, texts, and activities targeted tutor education and ongoing PD in a general sense, and a specific question about administrative duties and the preparation for those duties allowed administrators to describe development opportunities that reach beyond traditional perspectives of what constitutes tutor education and graduate PD. Administrator responses help to create snapshots of the myriad ways that graduate student consultants and administrators are prepared for their work, how they are compensated for their work, and what activities may lend themselves to the development of soft skills that transfer to careers beyond graduate school.

For additional information to support survey responses, and to allow directors another venue for articulation, I also collected curricular artifacts and created short dossiers (see Appendix C) that illustrate how administrators organize PD and support graduate student growth in writing center studies, though few institutions provided documents in support of their survey answers. As I wish neither to minimize the academic, professional, or cognitive work that goes into curating a PD plan nor to further privilege semester-length credit-bearing courses as the superior option for graduate PD, I use the terms 'curriculum' and 'curricular artifacts' in a broad sense. A given PD program may be formalized in a class curriculum document or may be more in the form of calendars or topic outlines.

Results

Types of Writing Center Preparation and Compensation

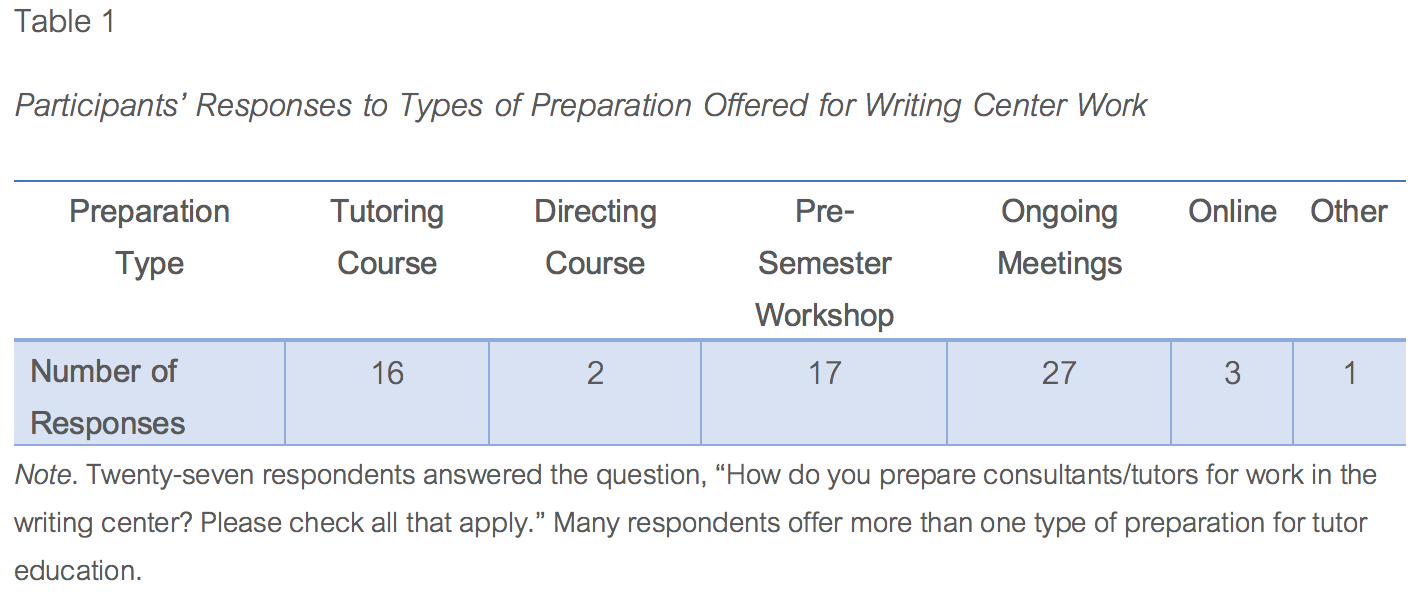

All 27 responding institutions in this study offer ongoing PD, while all but two also offer initial training (see Appendix B). More than half of the institutions offer more than one type of PD, including offering courses specific to writing center theory and practice or writing center administration, as shown in Table 1. Though many institutions do not offer these courses, when offered, courses last from five weeks, in the case of an optional course on Writing Center Program Administration/Writing Center Directing, to a full semester.

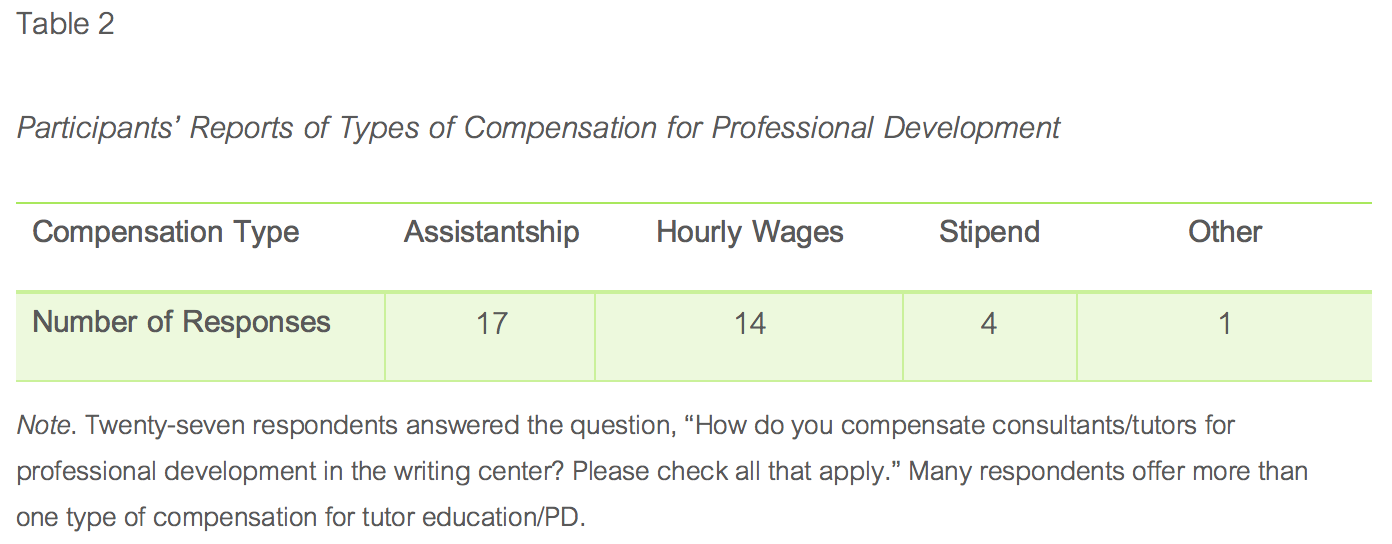

Julia Bleakney, in her recent study of tutor education published in this collection, found that 23% of responding institutions offer credit-bearing classes prior to and during writing center employment, as well as ongoing caption mandatory and voluntary meetings at 76% of the 142 institutions surveyed. What is clear to me through my small sample of 27 graduate institutions is that our field is prioritizing training and education in our writing centers for both graduates and undergraduates, though much of what we do with graduate consultants is very similar to what we do with undergraduate consultants, in terms of offering coursework and promoting involvement in the writing center beyond tutoring. Like undergraduate consultants, graduate consultants are offered opportunities in the form of initial and/or ongoing training, coursework, seminars, and regular staff meetings. While this can meet some needs, graduate consultants and graduate administrators have PD needs that go beyond training or coursework, particularly when it comes to entering the job market or taking new leadership positions. Attending ongoing meetings can mimic department or team meetings, while initial or pre-semester workshops can be similar to intensives or retreats, much like the IWCA Summer Institute. As shown in Table 2, these offerings are tied to financial compensation through hourly wages, assistantships, or stipends, illustrating that the PD is sufficiently valuable to the centers to require budgeting of both time and funds for those activities.

Although the prevalence of assistantships for PD (63%) is different than the common compensation of hourly wages for undergraduates, few institutions articulated how they differentiate between graduate and undergraduate participants in their PD offerings or specified activities that directly benefit those graduate consultants who enter the academy after degree completion.

Professional Development Goals for Graduate Consultants/ Administrators

As the field of writing center studies continues to discuss, develop, and implement assessments of our programs and student outcomes, writing center administrators should identify outcomes for our consultants by asking questions about our graduate audience's needs during and after their time in the writing center. Of the four institutions that submitted curricular artifacts, three, Institution 3, Institution 19, and Institution 18, have articulated goals, and both Institution 3 and Institution 19 have outcome-based goals that are measurable through formal or informal assessment. All three expect their students to develop reflective practices through their coursework. Bleakney argues that "reflection is a touchstone of ongoing tutor education," and that practicing observations and self-evaluations can help consultants to unpack the what, how, and why of the complexities of writing center work. This, in many ways, makes sense; as writing center consultants and administrators, we work from a common set of practices and theories, often grounded in the reflective, which provides a necessary forum for conversations about writing at our institutions. However, graduate students who are primed to enter the professoriate, administration, or careers outside of the academy may need additional outcomes that target their looming professions. For new writing center administrators, the questions of how to navigate the politics within an institution, particularly when quantifying an impact on a campus, may prepare graduate students for navigation in at least one context, even if that context changes as they shift status and institutions.

Graduate Professional Development Facilitators

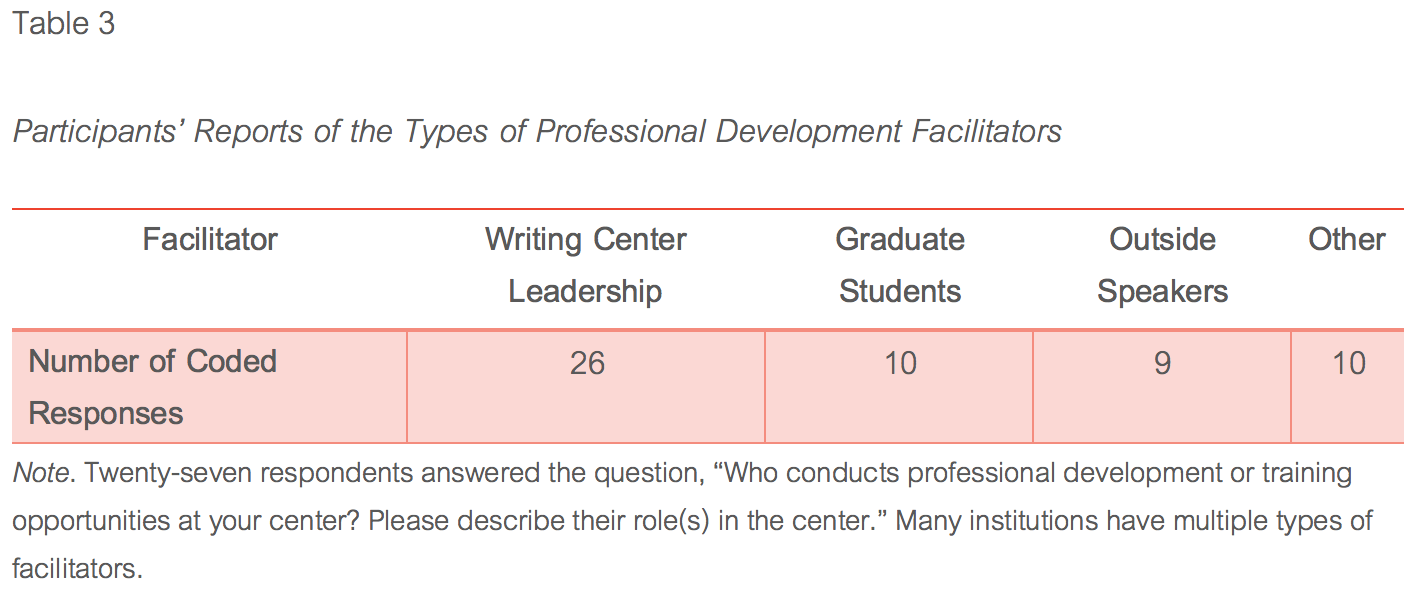

Much of the PD programming rests in the hands of writing center leadership, and there is room for collaboration with graduate consultants, particularly through graduate consultant presentations or mock tutorials, and through consultant-led discussions within those programs. Refer to Table 3 for categories of and responses to a question regarding PD facilitators.

Collaborative leadership within the writing center, similar to the model described by LeCluyse and Mendelsohn in their topoi-based approach, can provide opportunities for graduate consultants to reflect on, recognize, and address personal and center needs in their individual contexts.

Activities Highlighted in Writing Center Professional Development Programs

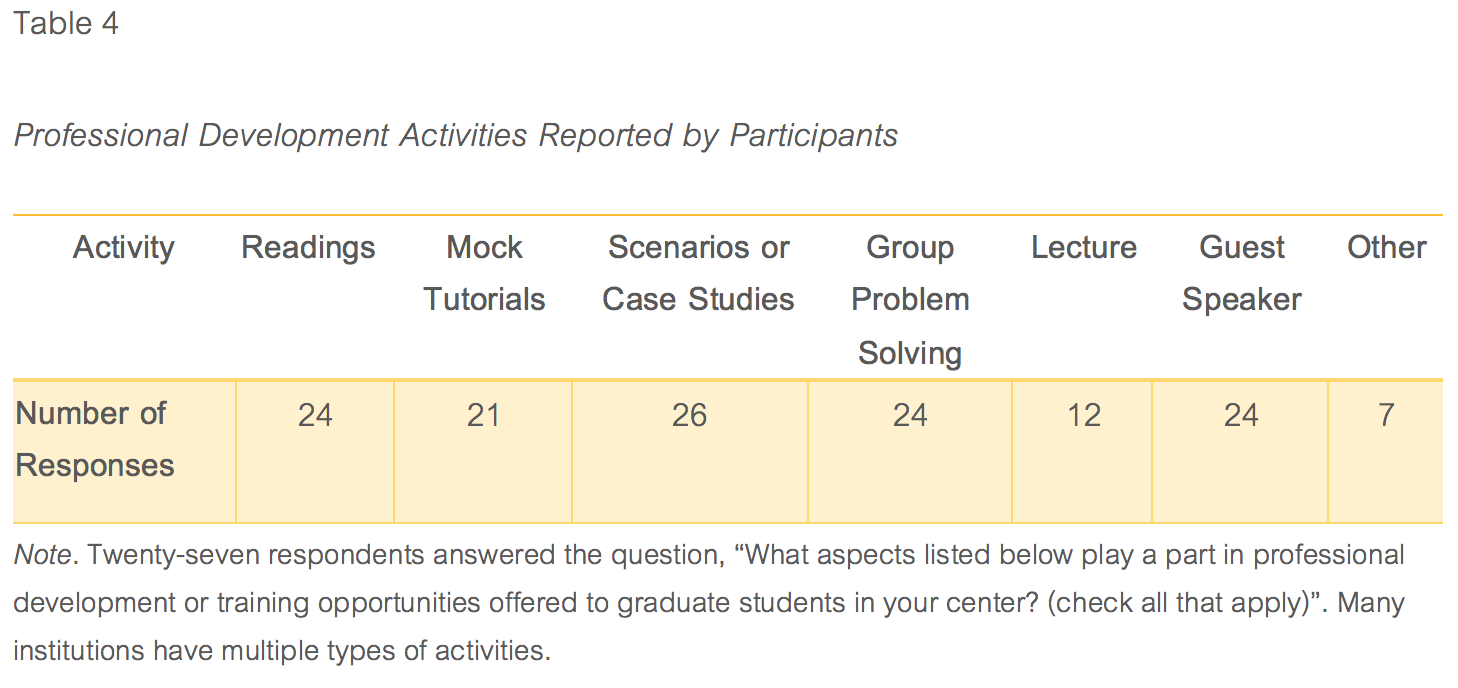

Across the responses, facilitators engage in similar activities, all of which have the potential to develop analytic, problem—solving, or interpersonal skills. All but one institution engages in scenario/case study discussions, and the majority engage guest speakers along with readings and mock tutorials, seen below in Table 4. These activities could easily shift from a focus on training that addresses particular skills to more meaningful PD that makes the labor of writing centers more visible through group problem solving of an administrative issue or through a mock tutorial that includes consulting with a faculty member on the construction of a writing prompt.

These results reinforce the emphasis on collaboration both inside and outside of the writing center. Additionally, institutions included mentoring models, shadowing or observation, and online discussions in their descriptions of PD opportunities for graduate consultants and administrators. For Institution 3, the activities specified in the assignment list indicate a focus on personal engagement with both writing center services and practices, and are scaffolded to slowly acquaint participants with the variety of theories, clients, and best practices for their particular population. The course activities and assignments lean heavily on reflection, asking participants to view their own perspectives and experiences in conjunction with the course readings and discussion. Institution 10 engages incoming tutors in individual sessions with current tutors and model paper analysis. They also discuss technical documents, including the consultants' resumes and cover letters. These results suggest that there are personal and improvisational elements to the activities, in both individual and group contexts, which may foster reflective practice.

Writing center administration at Institution 18 provides an activity that specifically benefits graduate students who are not only collaborating with PhD students in the writing center, but are also working on their own projects. Between meetings, participants are expected to complete a formal observation, and within meetings they are challenged to complete dissertation analysis, in conjunction with a discussion of disciplinarity and discourse. This is the only example of an in-depth engagement with graduate writing models, though Institution 3 writing center's PD program addresses graduate writing through readings. Multiple institutions use modeling, but a specific focus on models of graduate contributions where graduate consultants are challenged to assess current literature produced by their peers and to create their own scholarship may help them feel more confident about moving into careers that may require scholarly publication.

Beyond tutorials, modeling, and conversation, administrative experience within writing centers seems to function as PD outside of structured curriculum or meetings. Twenty-one institutions indicated that graduate employees had some degree of administrative responsibility, ranging from the very minimal (record keeping) to a designated position of graduate assistant director or coordinator. These graduate assistant directors and graduate coordinators occupy positions described as competitive and which require prior writing center experiences. These graduate administrators perform a number of duties (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Duties and administrative work performed by graduate employees.

The range of experiences, expectations, and opportunities for administrative work mirrors the responsibilities of writing center professionals and ultimately allows graduate writing center consultants and administrators to experience components of writing center work before entering the job market. Collaboration with faculty, development and delivery of presentations, workshop creation, supervisory duties, and mentoring models become part of many faculty positions, as well as writing program administration positions. Coursework in administrative theory in the form of writing center or writing program administration is offered at some institutions and can help to acquaint graduate students with theories, but for those students expressing interest in, or submitting applications to, positions in writing center leadership, providing more development opportunities that target directorships, professorships, or general administrative duties could assist them in the transition to the larger world of academia. PD through engagement with writing center administration that targets time management, client relations, collaboration, supervision, and detailed record keeping, all with a reflective angle, can benefit consultants in any chosen field. Regardless of intentionality, these activities may prepare graduate writing center employees for the reality of writing center work at the same time that they allow graduate consultants to determine if the administrative or clerical side of writing center work even interests them. If we know more of what to expect when we take positions in writing center leadership, perhaps the transition can be smoother and less fraught with stress or uncertainty.

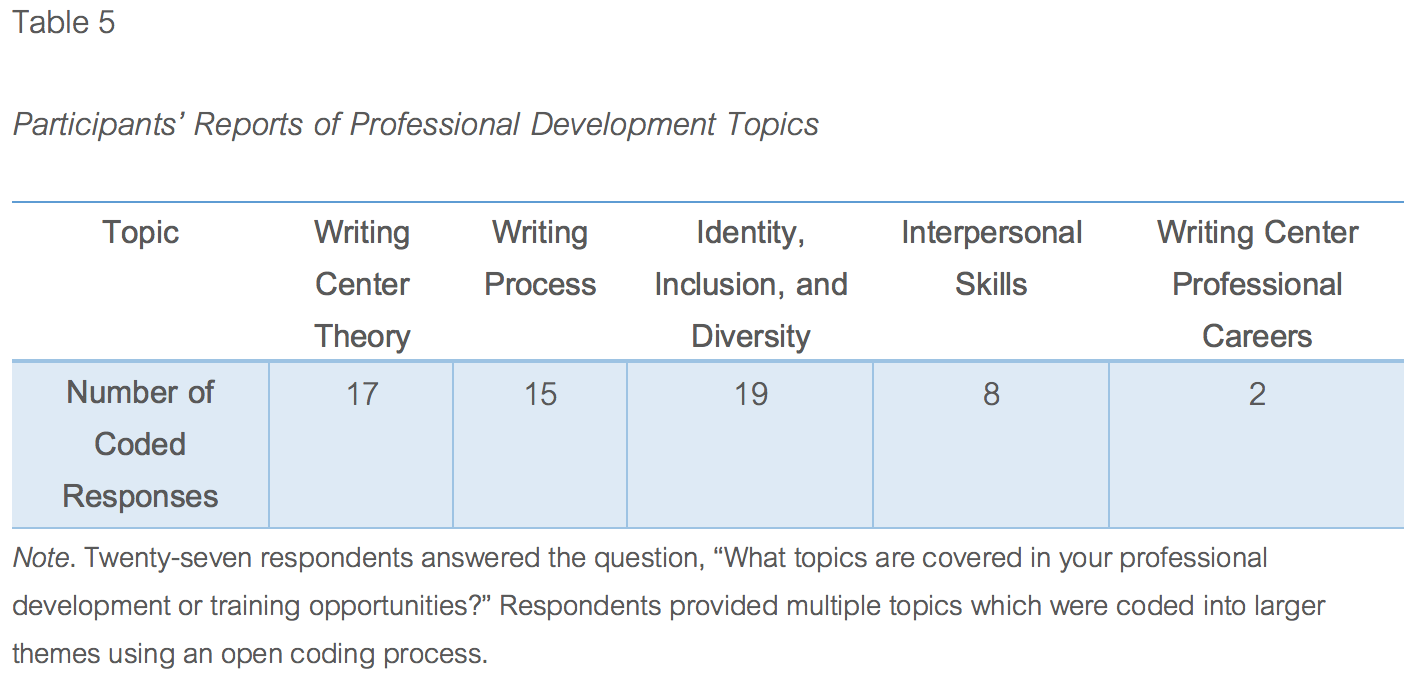

Topics included in PD opportunities

Many topics discussed in PD have potential for immediate impact (see Table 5). For example, the emphasis on writing process could have outcomes for graduate consultants beyond the walls of the writing center, particularly those who have teaching positions during their graduate tenure. Also, 70% of responding institutions emphasize "Identity, Inclusion, and Diversity," topics that may help future writing center administrators understand their roles within institutional and academic structures that are complicit in oppression. Stressing this topic, too, serves to promote discussion of the writing center's role in addressing oppression at the institutional level. One response specified that a question consultants must grapple with includes "what to do if a writer brings in an overtly racist piece," a topic that is quite pertinent now. While this topic may involve developing a discrete skill for helping a writer to see what they can do to reduce prejudicial thinking in their writing, addressing the issue through a discussion of the institutional mission may help graduate administrators conceptualize the way they can prepare staff to work with student writers. Writing center administrators also emphasized discussions of identity, inclusion, and diversity in terms of specific populations that use the writing center: graduate students, adult learners, veterans, student-athletes, returning students, dissertation writers, LGBTQ learners, anxious writers, and inexperienced writers. The responses indicate a focus on using inclusive pedagogy and language within the institutional context, and included strategies for working with writers composing at different levels, which is necessary for those graduate students who intend to go on to teaching positions, whether they are elementary, secondary, or postsecondary.

Other topics included developing a growth mindset about writing center work and developing the ability to learn through experience and from theory. One institution focused specifically on "how to collaborate with and learn from fellow tutors, fellow writing center administrators, and most of all, from one's tutees. (What do we all bring to the table and how we can work most productively to employ what's brought to the table by all in our interactions?)." Actively engaging with their peers and administrators within a nonhierarchical context is valuable for both graduates and undergraduates, but expanding this conversation to discuss what happens when you interact within a hierarchy could be even more valuable to future writing center professionals who would like to embody writing center values in interactions with upper administration or faculty who may try to downplay the institutional contributions of writing center work. Graduate PD also, of course, covers session protocols to prepare graduate consultants to work successfully within writing sessions.

Implications for Directors

This study has a small sample, and the results cannot be generalized beyond these participants. However, within this sample, some PD trends reveal that participating institutions provide

- a grounding in writing center theory and best practice through readings and discussion,

- an emphasis on observation and reflection for both learning and PD evaluation,

- a focus on cultural sensitivity for native and non-native speakers of English, and

- an understanding of writing process, genre, and discipline in the context of the writing center.

Because time for PD is limited by both budgets and logistics, facilitating meaningful discussions that cover a variety of perspectives can be challenging. The bibliography assembled from submitted texts in the survey and curricular artifacts in Appendix D is divided according to emergent themes, so that writing center directors and tutors can potentially divvy up the readings for writing center reading groups or literature circles. Creating reading groups that can lead discussions or share expertise on particular subjects as part of a community of practice may be an effective way to increase the number of perspectives and theories with which graduate consultants can engage. Adding texts like The Working Lives of New Writing Center Directors by Nicole Caswell, Jackie Grutsch McKinney, and Rebecca Jackson, or Anne Geller and Harry Denny's "Of Ladybugs, Low Status, and Loving It: Writing Center Professionals Navigating Their Careers," can spark conversations about the options for writing center administrators and the benefits or drawbacks for particular professional classifications within writing center work. (E)Merging Identities: Graduate Students in the Writing Center, which includes Natalie Singh-Corcoran's piece "You're Either a Scholar or an Administrator, Make Your Choice: Preparing Graduate Students for Writing Center Administration," is an excellent text for complicating the graduate experience as directors help graduate students make critical decisions about their paths in or out of the academy.

Some institutions may frame writing center work as service-oriented, rather than scholarship-oriented, neglecting to position the work as equal to that of the professoriate. For those continuing in the academy, increased and intentional engagement with research may help emerging scholars and administrators see the field of writing center studies as integral to the field of rhetoric and composition, to outside disciplines, and to higher education as a whole. Faculty directors play a key role in helping graduate consultants seek out PD opportunities that may include publishing within the field of writing center studies. Julie Eckerle, Karen Rowan, and Shevaun Watson suggest that faculty directors "help graduate students learn how to write proposals for conferences and seek out publication opportunities" in addition to advising those students on opportunities for funding, to provide "them with academic survival skills that they will need long after they leave their writing center posts" (49). Although some PD programs encourage intentional engagements with careers or research in the field of writing center studies, writing center administration, and writing program administration, more could be done to increase graduate engagement within the field through publishing in The Peer Review, The Dangling Modifier, or participating regional and national conferences. These venues often serve as entry points for emerging scholars to reflect on their own experiences while connecting to both theory and practice.

For new directors and those who are thinking of pursuing writing center administration as a career, there are some opportunities to learn and engage in writing center work through professional organizations like IWCA's Mentor Match, which seeks to connect new and experienced writing center administrators. Unfortunately, some of these opportunities are more designed for those who have secured full-time careers. However, for graduate students who may not have opportunities to participate in the IWCA Mentor Match program (which is often stretched beyond capacity by new full-time directors), mentoring could be done at the regional or institutional level. Holly Ryan's chapter in this collection, "First Things First:An Introduction to Administration at a New Directors' Retreat," describes such a program that is open to graduate students. The IWCA Graduate Organization hosts conversations on Twitter and Facebook, as well as at the annual conference, and takes on topics like the pathways into writing center careers and the tensions in prioritizing staff or faculty positions when initially entering the job market. Graduate students who get involved with the organization may find this to be a particularly useful support network as they work through graduate writing center scholarship or enter the job market. At the institutional level, writing center administrators can be open about the ways writing center work manifests in their context, perhaps reducing a graduate consultant's uncertainty about the choice to become a writing center professional while preparing them to navigate the political climates present in various institutions. When writing center administrators are transparent about institutional working conditions, graduates may be more empowered to move more confidently into their new positions and better articulate their own goals and concerns within writing center studies.

As I reflect on my graduate experience and consider the experiences of others, I believe that additional engagement in campus or classroom outreach activities, like offering targeted workshops to varied populations, may help those pursuing academic or writing center administrative positions. I know that working with my mentor to offer writing workshops for students working on civil engineering projects allowed me to interact with faculty to help their students reach goals in a group setting. These outreach opportunities often require collaborative conversations, an understanding of student needs in writing across disciplines, and the ability to frame writing center work for those who may be unfamiliar with writing pedagogy.

Graduate students who are entering the job market need additional support from their directors and within their programs. One center addresses "using writing center education and experience when applying and interviewing for faculty positions" as a topic. Addressing these topics, in or out of a mentoring context, can help ease the stress of entering the job market by helping graduate students understand what is required when trying to obtain post-graduate employment, particularly within the academy. Graduate consultants and administrators may also benefit from conversations that help them understand the ways writing center directors engage with other campus programs or entities, such as writing across the curriculum or writing in the disciplines; as graduate students to learn how WAC/WID programs work and the potential for political tensions that exist across disciplinary lines, they can better prepare for the collaborations and negotiations of writing center administrative or faculty work. Through PD that moves beyond just-in-time training focused on consultations, we can better prepare the next generation of writing center administrators to face the academy.

What's Next?

I originally sought to explore and unpack how other graduate consultants and administrators are prepared for their work in and beyond writing centers through PD activities. Writing center administrators are preparing graduates for immediate work, but are not necessarily looking forward at their careers in a deliberate manner. I found that institutions are offering a wide range of opportunities that suit their contexts; furthermore, graduate students are engaging in meaningful work within writing centers, though that work may not necessarily connect to their goals beyond their time in the writing center. What we do not know is what those graduate consultants are gaining through their work in writing centers, or if the outcomes that we are specifying do, indeed, transfer beyond the academy. We need to identify those outcomes that meet graduate students' career goals and incorporate meaningful PD opportunities that help them to fulfill those goals. These goals and outcomes should be linked to context-specific institutional or writing center missions, as graduate consultants are primarily hired to meet institutional needs.

As directors, we can reflect on our own paths to writing center work and the needs we had as we entered the field and use these experiences to structure our PD opportunities for graduate students. We can learn from emerging research, such Jennifer Hewerdine's dissertation, Conversations on Collaboration: Graduate Students as Writing Program Administrators in the Writing Center, examining the work of graduate writing center administrators. Her research indicates that, despite experience in graduate administrative work, those moving into writing center or writing program administration feel unprepared for the political navigation required of that work. Though directors may not be able to fully prepare graduate students for the complicated political relationships involved in our labor because these relationships are often non-generalizable and context-specific, exposure to and engagement with directors, internships, conference presentations, and writing center publications can ease students' transitions into their careers. Established directors can also guide graduate students to get involved in the IWCA Mentor Matching Program, the Summer Institute, and the St. Cloud Graduate Certificate in writing center administration so they can create professional networks and expand their graduate consultant and administrator communities of practice beyond the institutional level.

As writing center administrators, we must continue to ask where these graduate consultants who may become our "professional descendants" are going, how they are getting there, and what they experience when they arrive to create more specific and intentional outcomes for graduate writing center work and development. The survey described in this study offers an exploration of consultant education at the graduate level and begins to explore models for that education, but there is much work to be done to more closely examine what it means to participate in PD at the graduate level. As scholars continue to explore the ever-expanding world of graduate writing center work, administrators must value and expand the education we offer students through both courses and continuing opportunities. As a field, we have the opportunity to collect varied models of PD and to encourage research that determines effective practices for different types of contexts, institutions, consultants, and writers. This moment and these conversations give us a chance to bridge the gaps between graduate work and that of faculty and administrators, and an opportunity to continue to build programs that produce a pool of writing center professionals who can continue to develop this evolving field.

Works Cited

"Become a Writing Tutor." Writing Center, Colket Center for Academic Excellence, 20 April, 2018, www.coloradocollege.edu/offices/colketcenter/writing-center/Become_a_Writing_Tutor.html.

Bleakney, Julia. "Ongoing Writing Tutor Education: Models and Practices." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Bleakney.html.

Bruce, Shanti, and Ben Rafoth. ESL Writers: A Guide for Writing Center Tutors. 2nd ed., Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook, 2009.

Caswell, Nicole I, et al. The Working Lives of New Writing Center Directors. UP of Colorado/Utah State UP, 2016.

Clark, Irene. "The Writing Center at the University of Southern California: Couches, Carrels, Computers, and Conversation." Writing Centers in Context: Twelve Case Studies, edited by Joyce A. Kinkead and Jeanette G. Harris, NCTE, 1993, pp. 97-113.

The Dangling Modifier: An International Newsletter by and for Peer Tutors in Writing. NCPTW, edited by Caitlin Vandermeulen et al., https://sites.psu.edu/thedanglingmodifier/.

Eckerle, Julie, et al. "The Tale of a Position Statement: Finding a Voice for the Graduate Student Administrator in Writing Center Discourse." Nicholas, et al., pp. 39-52.

"Events/Summer Institute." International Writing Center Association, 20 April, 2018. writingcenters.org/summer-institute/.

Geller, Anne Ellen, and Harry Denny. "Of Ladybugs, Low Status, and Loving the Job: Writing Center Professionals Navigating Their Careers." Writing Center Journal, vol. 33, no. 1, 2013, pp. 96–129.

Gillespie, Paula, and Neal Lerner. The Allyn and Bacon Guide to Peer Tutoring. 2nd ed. Pearson, 2004.

Gillespie, Paula, and Neal Lerner. The Longman Guide to Peer Tutoring. 2nd ed. Pearson Longman, 2008.

Harris, Muriel. "A Multiservice Writing Lab in a Multiversity: The Purdue University Writing Lab." Writing Centers in Context: Twelve Case Studies, edited by Joyce A. Kinkead and Jeanette G. Harris, NCTE, 1993, pp. 1-27.

Hewerdine, Jennifer M. Conversations on Collaboration: Graduate Students as Writing Program Administrators in the Writing Center. Dissertation. Southern Illinois University, 2017. January, 2018.

Hughes, Bradley. "The Tutoring Corona: New Perspectives on Professional Development for Tutors." Another Word from the Writing Center at the University of Wisconsin&nmdash;Madison. 5 September, 2017, writing.wisc.edu/blog/the-tutoring-corona-new-perspectives-on-professional-development-for-tutors/.

International Writing Center Association. https://www.facebook.com/internationalwritingcentersassociation/.

@IWCAGO. International Writing Center Association Graduate Organization. https://twitter.com/iwcago.

@IWCA_NCTE. International Writing Center Association. https://twitter.com/iwca_ncte?lang=en.

Jackson, Rebecca, et al. "(Re)Shaping the Profession: Graduate Courses in Writing Center Theory, Practice, and Administration." The Center Will Hold: Critical Perspectives on Writing Center Scholarship, edited by Michael A. Pemberton and Joyce A. Kinkead, Utah State UP, 2003, pp. 130-50.

Koppelman, Zachery. "Crash-Course Writing Consultant Training." WCenter Listserv. Lyris, http://lyris.ttu.edu/read/messages?id=25279624#25279624. 28 January, 2018.

Langan-Peck, Jessica. "Tutor Training Manual Resources." WCenter Listserv. Lyris, http://lyris.ttu.edu/read/messages?id=24684553#24684553. 28 January, 2018.

Le Cluyse, Christopher, et al.. "IWCA Mentor Matching Program." International Writing Centers Association, 23 Sept., 2013. writingcenters.org/2013/09/23/iwca-mentor-matching-program/.

LeCluyse, Christopher and Sue Mendelsohn. "Training as Invention: Topoi for Graduate Writing Consultants. Nicholas, et al., pp. 103-18.

Midwest Writing Centers Association. 20 April, 2018. http://www.midwestwritingcenters.org.

Nicholas, Melissa, et al., editors. (E)Merging Identities: Graduate Students in the Writing Center. Fountainhead Press, 2008.

The Peer Review. Edited by Rebecca Hallman et al. International Writing Center Association. http://thepeerreview-iwca.org.

Pemberton, Michael A., and Joyce A. Kinkead. "Introduction: Benchmarks in Writing Center Scholarship." The Center Will Hold: Critical Perspectives on Writing Center Scholarship. Kindle ed., Utah State UP, 2003.

Rafoth, Ben. A Tutors Guide: Helping Writers One to One. 2nd. ed., Heinemann, 2005.

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. 6th ed., Bedford/St. Martins, 2016.

Ryan, Holly. "First Things First: An Introduction to Administration at a New Directors' Retreat." How We Teach Writing Tutors: AWLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Ryan.html.

Singh-Corcoran, Natalie. "You're Either a Scholar or An Administrator, Make Your Choice: Preparing Graduate Students for Writing Center Administration." Nicholas, et al., pp. 27–38.

"Writing Center Administration (Graduate Certificate)." St. Cloud State University Graduate Programs, 20 April 2018. www.stcloudstate.edu/graduate/writing-center-admin-cert/default.aspx.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to the IWCA Dissertation Grant Committee, which helped make this study possible. Special thanks to the professional staff of the Colorado College Writing Center, and to Jennifer Hewerdine for her support throughout this process. Ted Roggenbuck and Karen Johnson's mentoring has been invaluable to me.

BIO

Kat (kbell@coloradocollege.edu) is the Director of the Ruth Barton Writing Center at Colorado College. Her dissertation focuses on the preparation and perceptions of graduate writing center work. She is a member of the Colorado Wyoming Writing Tutors Affiliate through IWCA.