CHAPTER TWELVE

Teaching, Learning, and Practicing

Professionalism in the Writing Center

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Tom Earles

University of Maryland, College Park

Leigh Ryan

University of Maryland, College Park

Managing the Writing Center as a Professional Workplace

Writing centers help writers. To accomplish that task effectively, we educate our tutors in various aspects of writing center theory and practice. In class or meetings, we discuss articles by Stephen North and Muriel Harris, ways to work with basic or multilingual writers, and terms such as invention and ethos. This training and its practice come with benefits for tutors, like helping them develop better listening, problem-solving, and communication skills, and increase their patience and empathy. In fact, The Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project notes the influence that tutoring has on tutors' college experience and often on their lives (Kail, Gillespie, and Hughes).

Since we typically employ student workers in a university setting, our training programs also offer an opportunity and an obligation to develop readiness for the workplace. Put simply, we show tutors how to conduct themselves in a professional setting. We do this partly to establish, communicate, and oversee guidelines that assure the writing center's smooth operation. Tutors need to know the answers to questions like "What's the procedure if I'm sick or running late?" and "Are there expectations for dress or behavior?" Furthermore, some of this training involves ethical considerations, and so in addition to discussing ways of making sure the writer does the work, we talk about matters such as dealing with plagiarism and not commenting negatively about a teacher's assignment or grading or teaching. Some of this tutor training spills over into that provided for receptionists, for they, too, need to be reminded that "you will hear things about students, teachers, and assignments, but what you hear stays within these walls."

This professional aspect of our training also acknowledges a responsibility that we see as incumbent upon writing center administrators–that of preparing our tutors and receptionists to function in the workplace after graduation. Indeed, employers expect and value professional behavior in their new hires. While Marvin Krislov and Steven S. Volk note in their article "College is Still for Creating Citizens" from The Chronicle of Higher Education that "employers are still looking for those characteristics that have long been central to a liberal-arts education: skills of communication and critical thinking, innovation and collaboration, integrity and responsibility," one study goes so far as to suggest that certain skills are even more important than a student's choice of undergraduate major. These include written and oral communication, ethical judgment, integrity, critical thinking, and responsibility ("It Takes More Than A Major").

The writing center is uniquely positioned to help develop professional awareness and skills in the tutors and other students we employ. To be sure, most arrive with a sense of professionalism and good work ethics, but all need to know their writing center's specific guidelines regarding paperwork, procedures for calling in sick, and other matters. A few need even more general guidance about workplace behavior, however. Among other things, it's here that they can acquire some basic skills and habits that are crucial in a professional setting–showing up on time, meeting deadlines, dressing and behaving appropriately, working well with others, and properly answering a phone.

When we began as writing center administrators, we saw preparing tutors for the workplace as a relatively simple task. To assure no misunderstandings, we developed written guidelines for practice and behavior. We discussed them at each semester's orientation and in the tutor education class, and we dispensed them as appropriate in our handbook and on our listserv. But the truth is, they never felt quite right. For one thing, our guidelines seemed rule-bound. Though tutoring may sometimes be directive, our list of do's and don'ts seemed peculiar in an environment that largely promotes nondirective tutoring. And we found that as the semester progressed, we offered reminders more often than we liked. Over time, we wondered if there was a better way to get our messages across.

Eventually we settled on an approach to develop professional guidelines that put tutors more in charge, one that didn't simply ask them to follow rules, but rather empowered them by asking them to develop their own "Code of Professionalism." Tutors would formulate guidelines and, in the process, consider why they were important and how they should be communicated. It is that approach we wish to share here, but first we will provide some background on our writing center and some issues we faced. While those details may not apply directly to your writing center, they will help you understand how we proceeded and think about what you might consider in your own writing center to adapt aspects of our process.

Eventually we settled on an approach to develop professional guidelines that put tutors more in charge, one that didn't simply ask them to follow rules, but rather empowered them by asking them to develop their own "Code of Professionalism." Tutors would formulate guidelines and, in the process, consider why they were important and how they should be communicated. It is that approach we wish to share here, but first we will provide some background on our writing center and some issues we faced. While those details may not apply directly to your writing center, they will help you understand how we proceeded and think about what you might consider in your own writing center to adapt aspects of our process.

Overseeing the University of Maryland Writing Center: Considerations and Challenges

How we run our writing centers and educate our tutors and receptionists to function within them is always context specific. A hallmark of any writing center is its unique culture, and many factors influence that culture, including the campus itself (e.g., population, size, mission, location, demographics) and the writing center's mission, size, location, layout, kinds of tutors (undergraduate, graduate, professional, faculty, volunteers), and number of tutors. Thus, it seems helpful to begin with a brief description of some influences that affected our decisions as we developed a Code of Professionalism with our tutors and, later, with our receptionists.

The University of Maryland College Park is a large, suburban, Research I institution. As the flagship of the University of Maryland system, admission is selective and has become more so in recent years. Our selective admission, for example, means we have very few basic writers, but our campus hosts many multilingual writers. Of approximately 38,000 students, 27,000 make up the undergraduate population that we serve, and many are commuters. Our tutor education is designed to reflect the needs of our campus population.

We face a number of challenges in overseeing our writing center, not the least of which is its size. In a given semester we have 60-70 tutors, including the roughly 20 enrolled in the tutor education course, plus 6-8 receptionists who are typically Federal Work Study students. Our tutors include mostly undergraduates, but also graduate students and community volunteers, several of whom are retirees. Only undergraduates take the required one-semester tutor training course (a 2-3 hour weekly class meeting combined with tutoring under supervision). Training for other tutors is handled largely on an individual basis by the administrative staff, none of whom are full-time except an administrative assistant who handles scheduling, budgets, supplies, and a myriad of other administrative tasks.

Because our center employs a large number of tutors, getting all tutors together is never possible. Even during the orientation meeting at the beginning of each semester, fully one-third of our staff might be juggling our activities with other campus obligations like marching band or a learning community retreat. During the semester, we schedule occasional social events like ice cream or pizza parties, and our ongoing training involves workshops and groups meeting over lunch, but attendance is typically low as we compete with classes, activities and jobs on and off campus, and commuting distances. We rely on our writing center listserv to communicate information regularly each week and to pass on other information as necessary.

Our large size also means that not all tutors know one another, even if they share similar schedules. We are busy from the first week and sometimes have 10-12 tutors on duty each hour. Some only work 3 hours a week; others work as many as 15 hours weekly. This lack of familiarity with fellow tutors seems to grant some anonymity, making it easier to call in with excuses for running late or missing work to finish a paper; less guilt accompanies inconveniencing a relatively unknown someone rather than "Abby" or "Yao."

Another influential factor is the center's ambiance. While we promote a friendly, relaxed atmosphere to make clients feel more comfortable, our tutors' and receptionists' behavior sometimes reflects this looseness in interesting ways. One tutor, a daughter of a professor, regularly changed her schedule to accommodate her father's trips to campus. She explained that she figured "we would understand," but her changes often left us scrambling to cover her appointments. In another instance, a new and seemingly half-asleep receptionist sported headphones; not only was he oblivious to clients arriving, but he addressed the administrator who asked what was going on with "Hey, dude." We wondered if they simply didn't know better. If so, it was our responsibility to make professionalism more transparent since we were also preparing them for the workplace after graduation. Supporting our reasoning, in a New York Times article, a recent graduate noted that the informality at some companies can mislead new hires:

Another influential factor is the center's ambiance. While we promote a friendly, relaxed atmosphere to make clients feel more comfortable, our tutors' and receptionists' behavior sometimes reflects this looseness in interesting ways. One tutor, a daughter of a professor, regularly changed her schedule to accommodate her father's trips to campus. She explained that she figured "we would understand," but her changes often left us scrambling to cover her appointments. In another instance, a new and seemingly half-asleep receptionist sported headphones; not only was he oblivious to clients arriving, but he addressed the administrator who asked what was going on with "Hey, dude." We wondered if they simply didn't know better. If so, it was our responsibility to make professionalism more transparent since we were also preparing them for the workplace after graduation. Supporting our reasoning, in a New York Times article, a recent graduate noted that the informality at some companies can mislead new hires:

'They see they can call everyone from the C.E.O. down by their first name, and that can be confusing–because what they often don't realize is that there's still a high standard of professionalism. ...[T]hese things are basic, but they require reminders: show up to meetings on time; be aware that you, yourself, are fully responsible for your work schedule. No one is going to tell you to attend a meeting.' In other words, young graduates mistake informality for license to act unprofessionally. (Worthen)

Professionalism Elsewhere?: A Survey of Some Literature

In writing centers like ours that employ traditional-age undergraduate tutors and receptionists, these positions can often be the first jobs these young people have, and they frequently balance classes and schoolwork with other jobs and personal lives. Because we recognize promoting professional behavior not only as a way to assure and improve our writing center's smooth operation, but also as a responsibility to the pre-professional students we employ and mentor, we began looking at what others had to say about professionalism itself, as well as how it related to college students and recent grads. A quick search revealed that we were not alone in our concerns about college graduates' preparedness for the workplace. One article bluntly states, "What do U.S. College Graduates Lack? Professionalism" (Bauerlein). Others echo this sentiment: "The Real Reason New College Grads Can't Get Hired" (White) and "The Skills Employers Wish College Grads Had" (Vasel). In addition, NPR reports that some schools offer short courses or units on "Professionalism 101" (Lee). And so we looked further for articles, studies, and reports. While we weren't aiming for a comprehensive review of literature, we hoped to get a better sense of what constituted the "soft skills" that employers wanted to see in their new employees and to gain a sense of what others saw as strong and weak areas.

In a study commissioned by Bentley University, "The PreparedUProject: An In-depth Look at Millennial Preparedness for Today's Workforce," all stakeholders, businesses, colleges, and recent and soon-to-be graduates acknowledge that they could better prepare students for the workforce. They focus specifically on areas like oral and written communication, professionalism and work ethics, and critical thinking and problem solving. The numbers in this study prove interesting, especially from the perspective of those new graduates seeking employment: nearly 40% of recent college graduates grade their own level of preparedness at a "C" or lower; 41% of college students grade colleges and universities at "C" or lower on how well they prepare students for their first jobs. Sixty percent of recent college graduates blame their lack of preparedness on themselves, while 42% blame their colleges and universities ("The PreparedUProject").

Similarly, the Association of American Colleges & Universities issued a report "Fulfilling the American Dream: Liberal Education and the Future of Work" in 2018 which used parallel surveys of business executives and hiring managers. Respondents supported internships or apprenticeships as places for students to learn and hone generalized skills: oral and written communication, critical thinking, ethical judgment and decision making, teamwork, and real-world application of skills and knowledge. However, the report notes that "only 33 percent of executives and 39 percent of hiring managers think that recent graduates are very well prepared to apply knowledge and skills to real-world settings" (p. 4). These results suggest that colleges and universities should find ways to help ensure that their students graduate with the skills to be successful in entry level positions and even beyond.

Since 2009, York College of Pennsylvania's Center for Professional Excellence, which is now the Leadership Development Center, has been conducting an annual national professionalism study. Their studies, which began with the 2009 study, identify key professionalism components across industries and occupations as well as on campus, and relate them to graduates in their first jobs. In 2013, they polled faculty across the country to learn more about students' demonstrations of professionalism, and they also sought information about professionalism in the workplace by surveying people who hire new college graduates. In part, their findings culminated in advice for graduates applying for jobs:

- Do not demonstrate a sense of entitlement. Respondents indicated that the undergraduate degree is just a start, but some applicants feel they have paid their dues by graduating.

- Control your on-the-job use of technology. Respondents suggested that many new hires need to be less connected to their cell phones and social media. At work, they should consider when direct conversations might be more appropriate than an email, for example.

- Be committed to doing quality work. Respondents noted that some new employees display a casual attitude and are willing to do work that is not as professional as it should be.

- Learn what it means to be professional. Respondents indicated that until more colleges assume responsibility for exposing students to professionalism, students must learn this for themselves.

- Remember appearance matters. Respondents indicated that appearance on the job matters and has an impact on the perception of one's competence.

Figure 1. York Center for Professional Excellence advice to graduate jobseekers.

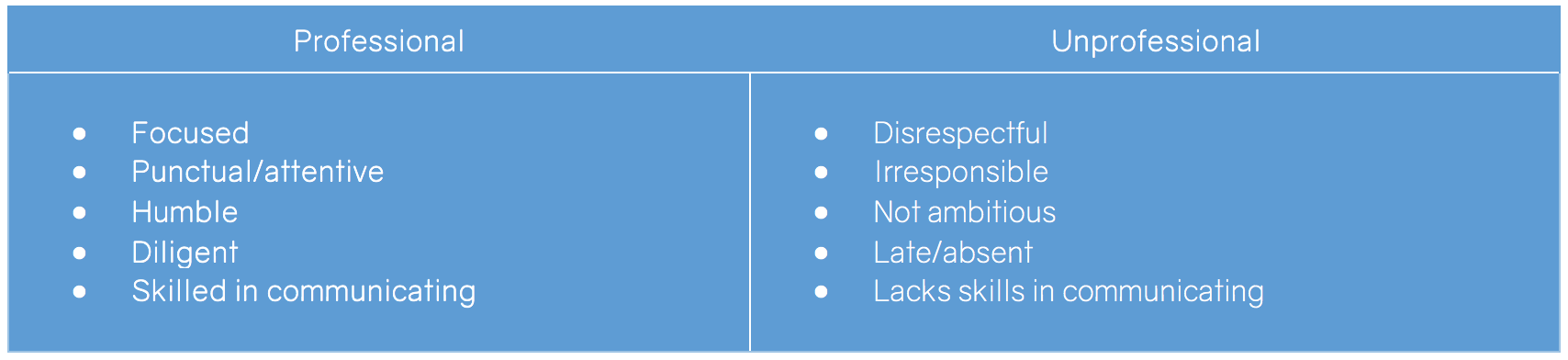

The 2014 survey queried career development professionals about higher education's involvement in developing professionalism in students, but it looked primarily at career development office offerings. While their programs on resume preparation and job searches fared well, more could be done in areas like projecting a professional image, dressing appropriately for work, transitioning from college to career, and using social media appropriately (12-13). In the 2015 survey, the York College researchers polled recent college graduates about their college to workplace experiences. Their surveys helped to affirm that professionalism and employability were very much on the minds of colleges and college graduates themselves. Their comprehensive studies identify and rank qualities of high-performing professionals and note those qualities that are most troublesome in newly hired graduates. The five qualities or behaviors most associated with being professional as an employee are shown in Figure 2:

|

| Figure 2. York Center for Professional Excellence five qualities most associated with being unprofessional. |

The reports and articles we found helped us to more completely identify what constitutes professionalism–or lack of it. They consistently reveal that some college graduates have much to learn about demonstrating appropriate soft skills in the workplace, especially those relating to interpersonal skills, a good work ethic, appropriate use of technology, and being focused and attentive. These reports and articles also indicate that many college graduates are not only aware of their need to learn more about professionalism, but they are also desirous of the opportunity.

What we learned proved useful. Not only were we in good company, but we saw even more clearly that we would truly be doing our staff a favor by helping them to better understand and assess the professional culture of a workplace. As they graduate and enter the workforce, there is value for our staff in learning about workplace etiquette, as well as in developing professional accountability and a positive work ethic.

In a recent radio interview that focused on college students and jobs, author Leslie Morgan Steiner commented on her own daughter who was about to start a summer position in a professional office. A conversation revealed that while her daughter knew enough to ask about appropriate dress, in planning her outfit for the first day she interpreted "casual dress" to mean "jeans and clogs." While this outfit might pass for "casual dress" on campus, it might well be inappropriate in a business setting. They went on to discuss covering tattoos, and using cell phones, and other matters that new employees like her daughter should consider (WTOP FM, April 25, 2018). Molly Worthen offers this analogy: "We should teach students traditional etiquette for the same reason most great abstract painters first mastered figurative painting. In order to abandon or riff on a form, you have to get the hang of its underlying principles." But how could we best accomplish this task of helping our tutors understand traditional etiquette? We decided that our center would develop a "Tutors' Code of Professionalism," a list of the professional behaviors expected of our tutors, and eventually we would develop a second one, a "Receptionists' Code of Professionalism."

Defining Professionalism and Soft Skills: Places to Begin

So what were all these "underlying principles" that we thought tutors ought to know? Efforts to find a concise and useful dictionary definition of "professionalism" did not prove to be easy; most definitions simply recast the word into something like "the skill or competence expected of a professional." Then we found this definition in a collaborative study, Are They Really Ready To Work?: "Professionalism/Work Ethic–Demonstrate personal accountability, effective work habits, e.g., punctuality, working productively with others, and time and workload management" (Cassner-Lotto, et al.). As a start, this one worked for us. Brief and succinct, the definition appeared in an an "Applied Skills" inventory, a list derived primarily from the partnership for 21st Century Skills. We also turned to other studies to see how they referred to these skills and found various terms: "employability skills" (Bauerlein), "workforce readiness" (Casner-Lotto, et al.), "preparedness" ("The PreparedUProject"), and soft skills (Vasel). In addition, we combed the annual professionalism surveys conducted by York College of Pennsylvania's Center for Professional Excellence to compile a list of key components of professionalism that we could share with our staff. These studies include communication and interpersonal skills, time management abilities, willingness to work as a team, work ethic, timeliness, attendance adaptability, respectful behavior, and maturity. Because these skills differ from knowledge about particular areas like marketing, accounting, or editing, they are considered soft skills. As Candice Olson, co-founder of The Fullbridge Program that was developed to bridge the skills gap between school and the workplace, explains, "Soft skills include attitudes and behaviors that correlate highly with career success. They are what enable people with different skills sets and personality that make up an organization to work effectively together and without friction. They are essential" (qtd. in Vasel).

Getting Tutor Buy-in as Stakeholders

We decided that the best way to promote tutors as stakeholders was to involve them. To truly make our writing center's "Tutors' Code of Professionalism" theirs, we structured its development to allow that to happen. Instead of imposing a list of expected behaviors, we would ask tutors to research and create their own Code of Professionalism. If they created it, we expected there would be buy-in, along with an increased sense of agency and accountability. Later we would repeat the same process with receptionists.

Putting tutors in charge meant creating a bottom-up, rather than a top-down, plan. A little research confirmed our ideas: bottom-up decision-making advantages include participation, motivation, empowerment, ownership, and knowledge (12Manage: The Executive Fasttrack). It was everything that we wanted! But our research also reminded us that bottom-up decision making can be rather complex and time-consuming, so we prepared for that, too, by allowing time and beginning with just a few tutors.

How We Did It

As we asked tutors to begin drafting ideas for our "Tutors' Code of Professionalism," we wanted them to have a sense of what others did–what others considered important and how they structured and phrased formal statements on professionalism. We searched for information from other writing center websites, formal statements or professional codes (Google searches proved helpful), and sections of tutor manuals and handbooks that we could show them. We hoped that these would help the tutors see the variety of considerations, and more importantly, help them understand the significance of context because much of what happens in each writing center is dictated by the institution's size, population, mission, location, and local culture.

Because our three-week Winter Session allows time for work on projects, and having a small staff lets us select experienced tutors who work well independently, that's when we planned to begin. But just before the December break, Maria, an excellent tutor and experienced two-year veteran whom we had hired for the Winter Session, stopped by. After an informal discussion, she offered to list some ideas during the break, and we gave her the handful of professional codes we had found. (As an aside, Maria later told us she thought we'd selected her because she had met her then-boyfriend, now husband, when he had a walk-in tutoring session with her. She wondered if she should have dated a client.)

On her own, Maria produced extensive notes. Clearly Maria, like many tutors, had already adopted and internalized her own personal Code of Professionalism. When Winter Session began, we asked our smaller, experienced group of tutors to add to the notes. Considering every aspect–duties as an employee, down-time, and interactions with clients, coworkers, and administrators–their task was to identify the etiquette or set of behaviors they found most important in maintaining professionalism in the writing center. The lists would be self-generated, inclusive, and collaborative. We provided them with the articles, reports, and other information we had located and suggested they use them for reference.

Giving them a few days to work, we encouraged tutors to converse freely among themselves and asked each tutor to email us a draft of their own personal list. We asked them to be comprehensive but concise and to provide no more than a page of bullet points. After tutors provided their thoughts, we asked the group to begin putting ideas together into categories. Underscoring the idea of self-generated, inclusive, and collaborative categories, we hoped that this phase itself would be a lesson in teamwork and professionalism.

Overall, the items tutors came up with, though often repeated from one list to another, varied widely from the general and vague to the very specific. Many listed behaviors like punctuality, general approaches to tutoring, and being respectful. A number of the suggestions were specific to the context of our writing center, like "post your nametag" and "stay near your tutoring station so the receptionist can find you." Others referred specifically to individual tutors, like "I need to do a better job reading emails from the administrators." A few even offered recommendations for handling situations out of the ordinary, like what to do if a client becomes aggressive or hits on you. They also offered suggestions for keeping busy when not tutoring.

This process continued as the tutors generated ideas individually and in groups of two or three and passed drafts back and forth, with one group expanding on and refining ideas, then sending them to another group to add new ideas and so on. Sometimes they sought feedback or advice from us, and every few days we checked to see where they were in the process.

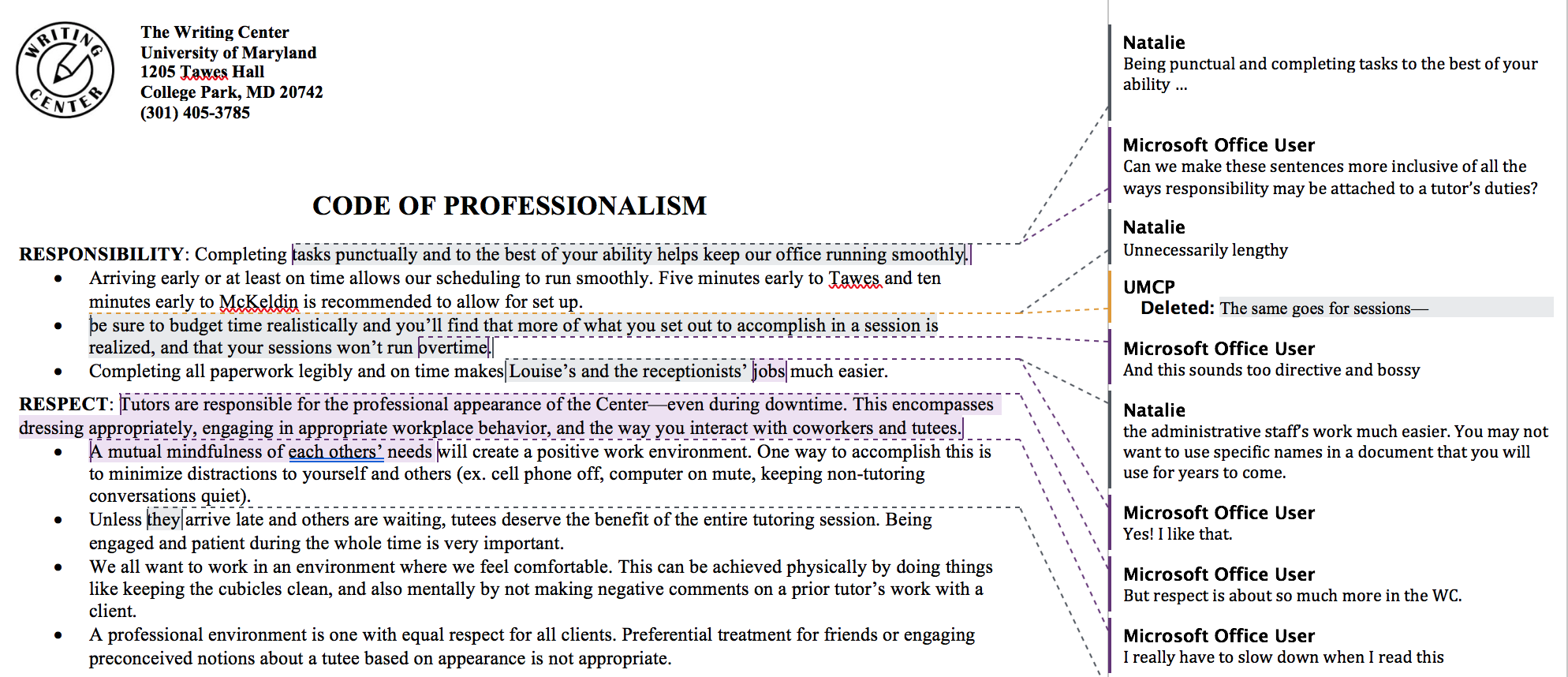

|

Figure 3. Draft of "Tutors' Code of Professionalism" with comments. |

As we progressed, difficult questions arose about how we should proceed. What should be included? How general or specific should this list be? How should items be organized? Most important to least important? Because many topics wouldn't be mutually exclusive, how should we decide what goes where when one falls into two or more areas? What tone should we use? How do we reconcile being largely non-directive tutors with recognizing the writing center as a comfortable, relaxed place, but one with some "rules"?

By the beginning of spring semester, we had a more or less "final" draft. As tutors returned, we asked every single one to review it and make comments and suggestions. In our first week of operation, it was possible to remove every tutor from the tutoring schedule for at least 30 minutes and allow them to focus on the "Tutors' Code of Professionalism." Most suggestions involved simple rephrasing, and we incorporated them easily.

What We Came Up With

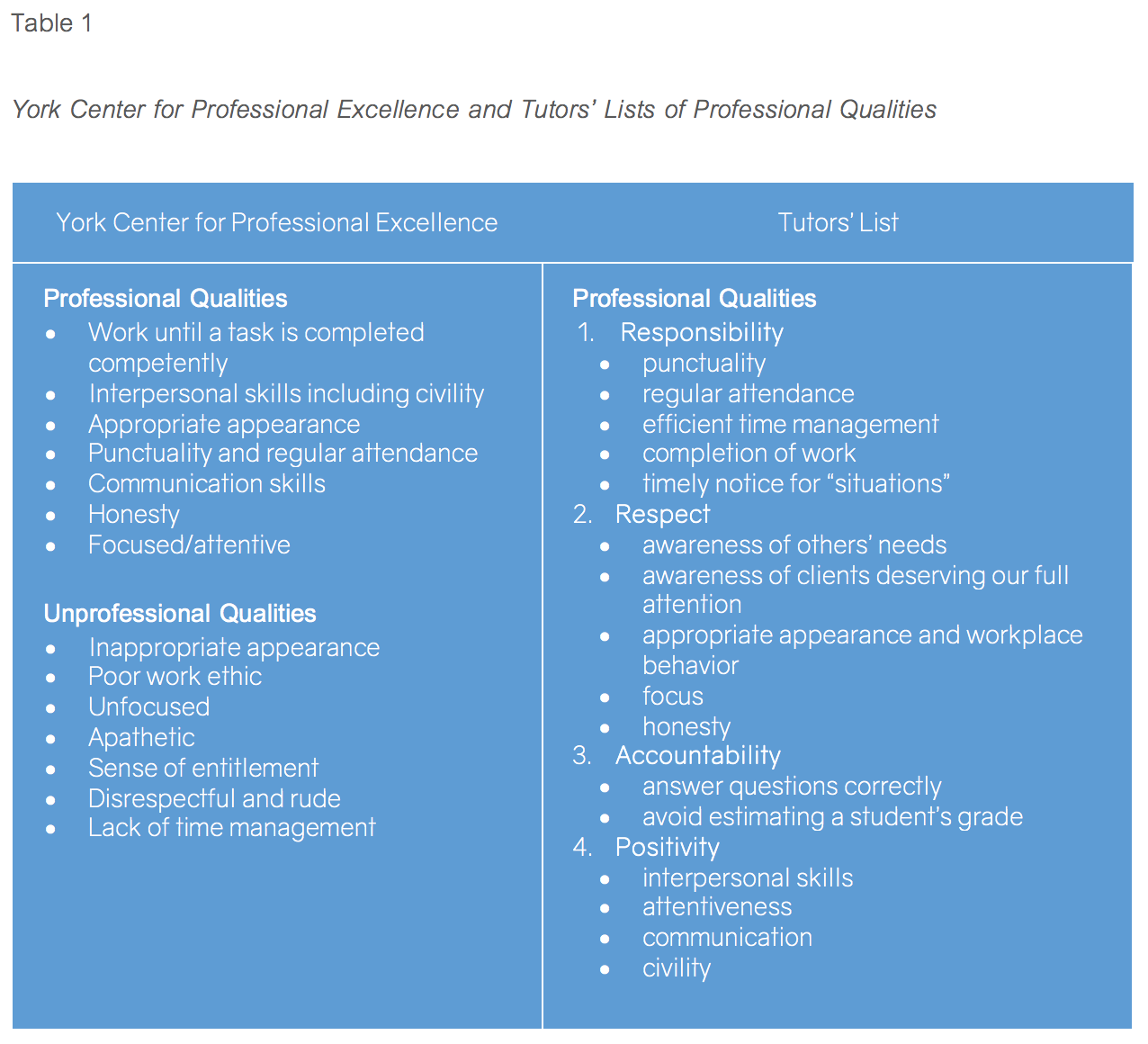

So what did tutors consider "professional," and how did their ideas compare with the lists generated in York College's findings? As the following table indicates, much was similar:

Much of what the tutors came up with in their draft fit under four broad categories: responsibility, respect, accountability, and positivity. Under "respect" was an example of the tutors being effectively unspecific. For instance, they framed respect as an awareness of others' needs, and of clients deserving our full attention. Much could fall under these two concepts. Under "accountability" they placed actions that might fall under ethical behavior, like making every effort to answer questions correctly, even if it means seeking help yourself, but here their language also became a touch more specific, for our tutors included a caution against trying to estimate a student's grade. And finally, important in just about any work environment, but especially crucial in a writing center that works face-to-face with students, were items they categorized under "positivity": interpersonal skills, attentiveness, communication, and civility. In many ways then, our tutors' draft corresponded quite a bit with York College's definitions, and we were confident in its appropriateness as a tool in teaching professionalism. The final product looked like this

.We followed a similar process for composing the receptionists' code, but it was less collaborative since our receptionists work one at a time and have little downtime. Though we arranged for some uninterrupted time for collaboration, the process was longer and required more directive input from administrators than the tutors' code had. However, receptionists and we, as administrators, were able to draw heavily on the tutor code itself, already in a usable form at that point. Like the tutors' code, the receptionists' code covers completing all work in a timely manner, respecting others, minimizing distractions, and maintaining focus.

How Do We Maintain Our Codes of Professionalism as "Always in Process"? Do They Work?

We regard both codes of professionalism as fluid or living documents that are always in process. This ongoing process means returning to codes regularly for revisions and updates, having each employee, new and returning, not only sign the code but also review it and make suggestions for improvement. In the years since we created the code, we have returned to it during the first weeks of each semester, carefully reconsidering it in full, and tasking the tutors and receptionists to join us. The codes are very much "living" documents that all staff are required to read and given an opportunity to contribute to.

What remains is the biggest question, one we imagine a reader might also be asking: Is it working? Does the existence of the code, and the regular revision process it goes through that involves our entire writing center, contribute to improved professional behavior by the staff? For the most part, yes. Although attendance concerns remain, they come up less frequently, and the reasons staff give for missing work or changing their schedules show a keener understanding of what is responsible and professional behavior. For instance, rarely does a tutor call out of work anymore because–as they put it–they have to study for an exam, but they might now request a shift off, days in advance, for an advising appointment or an orchestra dress rehearsal, often followed closely by an email from an advisor or conductor confirming the request. Questions over acceptable dress are nearly a thing of the past, and newer receptionists almost never have to be reminded about general customer service guidelines.

Every tutor and receptionist reads and signs the code each semester–we follow up and make sure–so they do know they are accountable for what it states. For new staff, our expectations are not only delivered orally but appear in writing. Regularly revisiting the Codes of Professionalism also serves as a reminder for returning receptionists and for experienced tutors who completed the tutor training class long ago or who previously tutored elsewhere. Unlike an email, which might never be read, the physical, signed copy shows tutors that we are invested in this project, that we are paying attention on an individual level, and that we are holding them accountable. It also results in more people actually reading our expectations and reflecting on what we are asking of them and why. The inclusive, collaborative process that created the codes of professionalism undoubtedly contributed to the increased participation and accountability. On the other hand, clearly not everyone reads carefully enough and some don't sign without some prodding. In addition, our annual requests for suggestions to revise the code produce limited results, which may mean indifference on the part of some staff members and a lack of the sense of ownership that drove the first drafts, since that staff is now long gone. We hope instead that it testifies to the good work done in drafting the originals.

Every tutor and receptionist reads and signs the code each semester–we follow up and make sure–so they do know they are accountable for what it states. For new staff, our expectations are not only delivered orally but appear in writing. Regularly revisiting the Codes of Professionalism also serves as a reminder for returning receptionists and for experienced tutors who completed the tutor training class long ago or who previously tutored elsewhere. Unlike an email, which might never be read, the physical, signed copy shows tutors that we are invested in this project, that we are paying attention on an individual level, and that we are holding them accountable. It also results in more people actually reading our expectations and reflecting on what we are asking of them and why. The inclusive, collaborative process that created the codes of professionalism undoubtedly contributed to the increased participation and accountability. On the other hand, clearly not everyone reads carefully enough and some don't sign without some prodding. In addition, our annual requests for suggestions to revise the code produce limited results, which may mean indifference on the part of some staff members and a lack of the sense of ownership that drove the first drafts, since that staff is now long gone. We hope instead that it testifies to the good work done in drafting the originals.

In particular, "The Tutors' Code of Professionalism" presents a unique opportunity to introduce professionalism into the tutor education course, especially as a writing center-generated text that new tutors can connect to their own context. In fact, they can sometimes be excellent contributors of new ideas to the code, perhaps partly because they are still very early in their habit-forming, and because they just haven't figured out what works (or doesn't) yet. And we'll admit, they are also eager to earn a good grade. In all cases, we make sure that if revisions are incorporated, all staff members are advised of changes so they can see that we take their suggestions seriously and that these codes remain, indeed, in process.

What Can You Do?

In addition to developing and maintaining our "Codes of Professionalism," we strive to frequently engage our staff in activities that underscore professionalism. We have listed some of those with suggestions below. We hope you will use some in your own writing center, adapting them to its particular needs and functions.

- Develop your own "Code of Professionalism" along with your staff. Involve your entire staff, delegate the task to a small group (perhaps volunteers or your tutor education class), or adapt it as a project for tutor down-time. Note: Don't assume that those most familiar with the writing center, i.e., long term employees, would be the most capable of drafting a substantive "code of professionalism." Sometimes fresh eyes offer surprising and insightful contributions.

- Initiate formal conversations about professionalism in tutor training sessions or staff gatherings. You might ask tutors to reflect on how they perceive the professionalism of offices and businesses they visit and how that affects their view of those establishments. Courteous treatment at a store or restaurant leads one to label that place as good; likewise, poor service from an employee makes one reject a store as a whole. Standards of customer service and appearances of professionalism (readiness, attentiveness, friendliness) usually translate easily from one setting to another. Ask tutors how they might apply those standards to their writing center or how they might react if a staff member in another professional setting had their feet on the desk, ignored customers, or wore something that might be deemed inappropriate for such a setting?

- Have focused conversations about professionalism and related soft or employability skills. You might choose one or two shorter articles from our bibliography or a section on professionalism in the workplace from a tutor training handbook to read and discuss as a group. How do the points relate to your writing center? What changes could be made in your center and how? If you have a tutor education class or regular meetings, make a list of important professional aspects to consider, like time management or use of technology, then focus on one or more over time.

- Work professionalism and its benefits into informal conversations whenever possible. Compliment positive behavior to reinforce it and do it publicly when you can. Make it loud and audible, or invite others to join the conversation with a "Wasn't that great that Chandler did such and such. . . ?" so they see that it matters and is acknowledged. They may choose to join the conversation (especially good if they are new to the staff) and add additional thoughts.

- Model professionalism. Perhaps the best way to teach professionalism in the workplace is to model professional behavior yourself. In communications to your staff, adopt the tone you would like them to use with you and others on campus. Let them hear you answering the phone the way you expect them to answer it. Greet students, faculty, and other visitors the way you expect your staff to greet them. Tutors will follow your lead, taking cues for what is appropriate and acceptable. Go a step further with other tasks they may be expected to do occasionally. If your writing center has a break room or food area, let your staff see you clean it (or ask a staff member to help you tidy it) from time to time, sending a message that this is everyone's responsibility and that they should not assume that someone else will clean up after them.

- Post reminders–notes for recycling, a script for answering the phone, a "please put paper in the printer" or "clean the microwave"–whatever is appropriate for your writing center. You may feel that you should not have to do this, but if it reminds people and saves you time and frustration, it's worth it. Besides, when you do have to speak to someone, you have the luxury of noting that "it shows you how here."

- Whenever appropriate, involve staff in decisions about the writing center that affect performance and professionalism. For example, when our center underwent construction, we asked staff how we might rearrange furniture, sign-in sheets, and technology to best accommodate the flow of people. Doing so gave them agency and ownership. The set-up we adopted was heavily informed by their suggestions and promotes professionalism by making the area more inclusive and welcoming.

- Involve tutors in professional activities with writing instructors. For example, sixty percent of our clients come from required courses in two writing programs and our tutors are invited to participate in reading groups and workshops sponsored by these programs for their instructors. We also plan our orientation activities to overlap so everyone can benefit from hearing prominent speakers. Not only do instructors notice the tutors' presence, but tutors' participation acknowledges their standing as professionals and allows them to explore and engage in aspects of composition and rhetoric as such, enriching them professionally. Several speakers have commented on how engaged our tutors were.

- Advertise tutors' professional activities. In campus, department, or program newsletters and websites, post announcements of tutors' presentations at conferences and publications in journals.

- Seek activities that promote interaction with other campus resources or partner with nearby institutions, perhaps secondary schools, to plan professional activities. Doing so offers advantages. If your school is small, pooling resources allows you to collectively offer events by tutors and for tutors that individual programs couldn't support. Tutors learn about other support programs (athletics, oral communication, math, etc.) through cooperative activities and can, for example, jointly present campus midterm or end-of-semester events. Aspects of professionalism cross all boundaries, so join with others to offer workshops on professionalism and tutoring to all campus or even local tutors. You might even co-sponsor a day-long conference focused on shared aspects of tutoring like establishing rapport and including tutoring on a resume effectively.

Be adventuresome! A day-long Saturday workshop with area college and high school writing centers that we hosted surprised us. Initially asked to present workshops to instruct our younger counterparts on tutoring, instead we paired high school and college tutors to jump-start discussions on specific aspects of tutoring. We learned so much from one another and ended by spontaneously sharing promotional videos.

Conclusion

The writing center is uniquely positioned to help develop skills of professionalism in the tutors and receptionists we employ. Looking again at those characteristics mentioned in Krislov and Volk's "College is Still for Creating Citizens"–communication and critical thinking, innovation and collaboration, integrity and responsibility–we see that the writing center can help develop those very same skills and qualities. We seek advanced skills in communication and critical thinking from prospective tutors–we look for it on their applications, in their writing samples, in remarks from their references, and perhaps in interviews before we hire them. And as they work with other students on their writing, we expect that tutors will further develop these skills over time. Tutoring many different students with many different writing assignments gives tutors little choice but to become more adept at innovation and collaboration. In these areas and others, like integrity, responsibility, and workplace ethics, administrators can work directly with tutors and receptionists to develop and refine their soft skills more fully.

Works Cited

Bauerlein, Mark. "What Do U.S. College Graduates Lack? Professionalism." Bloomberg View. 8 May, 2013, www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2013-05-08/what-do-u-s-college-graduates-lack-professionalism.

Cassner-Lotto, Jill, et al. Are They Really Ready To Work?: Employer Perspectives on the Basic Knowledge and Applied Skills of New Entrants to the 21st Century Workforce. Oct. 2006. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED519465.pdf.

"It Takes More than a Major: Employer Priorities for College Learning and Student Success." Association of American Colleges and Universities and Hart Research Associates, 10 April, 2013, https://www.aacu.org/leap/presidentstrust/compact/2013SurveySummary.

Kail, Harvey, Paula Gillespie, and Bradley Hughes. The Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project, UW-Madison,. 8 July 2015. https://writing.wisc.edu/pwtarp/?page_id=13.

Krislov, Marvin and Steven S. Volk. "College is Still for Creating Citizens." The Chronicle of Higher Education, 7 April, 2014, www.chronicle.com/article/College-Is-Still-for-Creating/145759.

Lee, Jacquie. "Professionalism 101: A Class On How To Get The Job." nprEd How Learning Happens, 15 June 2016. https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2016/06/15/473144435/professionalism-101-the-getting-a-job-class.

Steiner, Leslie Morgan. WTOP (Eastern) weekly radio segment. Washington, DC 103.5 FM, April 25, 2018.

The Association of American Colleges & Universities, "Fulfilling the American Dream: Liberal Education and the Future of Work." Hart Research Associates, 2018, https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/2018EmployerResearchReport.pdf.

"The PreparedUProject: An In-Depth Look at Millenial Preparedness for Today's Workplace." Bentley University, 29 Jan. 2014, https://www.bentley.edu/files/prepared/1.29.2013_BentleyU_Whitepaper_Shareable.pdf

Vasel, Kathryn Buschman. "The Skills Employers Wish College Grads Had," Fox Business, 30 Jan. 2014,

www.foxbusiness.com/features/2014/01/30/skills-employers-wish-college-grads-had.html.

White, Martha C. "The Real Reason New College Grads Can't Get Hired" Time, 10 Nov. 2013,

business.time.com/2013/11/10/the-real-reason-new-college-grads-cant-get-hired/.

Worthen, Molly. "U Can't Talk to Ur Professor Like This." New York Times Sunday Review, 13 May 2017, nyti.ms/2rci5wH.

12Manage: The Executive Fasttrack,

www.12manage.com/description_empowerment_employees.html.

Center for Professional Excellence, York College of Pennsylvania. Polk-Lepson Research Group: "2015 National Professionalism Survey: Recent College Graduates Report," Jan. 2015, http://www.ycp.edu/media/york-website/student-success/2015-National-Professionalism-Survey---Recent-College-Graduates-Report.pdf.

--"2014 Career Development Study," Mar. 2014, https://www.ycp.edu/media/york-website/student-success/2014-National-Professionalism-Survey---Career-Development-Report.pdf.

--"2013 Professionalism in the Workplace." Jan. 2013, https://www.ycp.edu/media/york-website/student-success/York-College-Professionalism-in-the-Workplace-Study-2013.pdf.

--"2013 Professionalism on Campus." Jan. 2013, https://www.ycp.edu/media/york-website/student-success/York-College-Professionalism-on-Campus-Study.pdf.

--"2014 Career Development Study," Mar. 2014, www.ycp.edu/media/york-website/student-success/2014-National-Professionalism-Survey---Career-Development-Report.pdf.

--"2013 Professionalism in the Workplace." Jan. 2013, www.ycp.edu/media/york-website/student-success/York-College-Professionalism-in-the-Workplace-Study-2013.pdf.

BIOS

Tom Earles (tearles@umd.edu) is the assistant director of the University of Maryland Writing Center and serves on the Executive Board of the Mid-Atlantic Writing Centers Association. His current research projects are on asynchronous online tutoring and intersections between creative writing and writing centers.

After directing the University of Maryland Writing Center from 1982-2016, Leigh Ryan (lr@umd.edu) retired as Writing Center Director Emerita. She is past president of the Mid-Atlantic Writing Centers Association (MAWCA), past secretary of the International Writing Centers Association (IWCA), and has served on the Advisory Boards and committees for IWCA, National Conference on Peer Tutoring in Writing, MAWCA, and the European Writing Centers Association. She has been honored with several awards for outstanding service: the IWCA Muriel Harris Award, the NCPTW Ron Maxwell Award, the UMD President's Faculty Award, the UMD College of Arts and Humanities Award, and the Prince George's County Historical Society St. George's Day Award. She has presented at regional, national, and international conferences. The 6th edition of her book, The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors, coauthored now with Lisa Zimmerelli, was published in 2016. She has also authored and co-authored many articles on writing centers.