CHAPTER EIGHT

Self-Efficacy and the Relationship

between Tutoring and Writing

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Kelsey Hixson-Bowles

Utah Valley University

Roger Powell

Buena Vista University

Self-efficacy, "people's beliefs in their abilities to produce given attainments" (Bandura 307), has long been of interest to writing center professionals and for good reason. We see self-efficacy manifest itself with students' confidence in their writing. Tutors and writing center administrators (WCAs) know that tutors often spend time in sessions helping students develop writing self-efficacy. These are often the students who begin sessions by saying "I'm a bad writer" or "I just don't feel confident with this paper." Our goal for these sessions quickly becomes helping the writer become more confident. And, as WCAs ourselves, we often consider ways we can prepare tutors to help students develop writing self-efficacy.

When examining several texts about writing self-efficacy in composition studies, writing center scholars quickly become aware that writing self-efficacy can impact how students learn to write. For example, M. Frank Parajes and Margaret Johnson found that the higher self-efficacy a student has in writing, the less apprehensive they are to write, and the better their writing performance. Parajes affirmed this claim in a literature review in which he found that a variety of studies in educational psychology show that self-efficacy impacted students' writing performances. In a 2011 article in Composition Forum, Dana Driscoll and Jennifer Wells used research from two empirical studies on writing transfer to argue that higher self-efficacy can promote the transfer of writing knowledge and skills. This finding is important because it highlights the ability of self-efficacy to help students within composition courses as well as to promote long-term growth and development in other contexts. Therefore, not only do WCAs and writing center tutors see the need for helping students develop self-efficacy in writing, but empirical research in composition studies and educational psychology also suggests that writing self-efficacy is important for student writers' success.

This is not a new subject in writing center studies. A quick search of the WLN archives reveals several recent articles published about student writers and their self-efficacy (e.g., Hawkins, Lape, and Lawson). Additionally, James Williams and Seiji Takakus' study examined how writing center visits impacted writers' self-efficacy and found that the more a writer visits the writing center, the higher their writing self-efficacy. Pam Bromley, Kara Northway, and Eliana Schonberg found that repeated writing center visits gave writers higher self-efficacy (similar to Williams and Takaku), but also that the more visits a student made to the writing center, the more likely they would be to transfer their writing knowledge skills from composition courses to other courses that required writing and even to professional contexts. The writing center therefore helped facilitate writing transfer when students gained more writing self-efficacy from their visits.

While this research is important and useful to writing center work, we began to wonder about writing center tutors. Specifically, we thought, what are writing tutors' experiences of writing self-efficacy? We turned to the literature on tutors' self-efficacy and found that less research exists to answer this question. In a 1995 WLN Tutors' Column, Margaret Bartlet offers a useful approach to helping tutors develop higher self-efficacy with tutoring by reminding them that it is okay to have moments of self-doubt but also encouraging them to spend time reflecting on how to overcome that self-doubt. Additionally, Shaun White's master's thesis found that a six-week training sequence increased participating tutors' self-efficacy in tutoring. These studies suggest methods for how tutors may develop tutoring self-efficacy. However, though such scholarship is useful, we are still left with questions: what role does writing self-efficacy play in tutoring writing? If writing self-efficacy impacts writing performance, could it also impact tutoring self-efficacy and/or performance? Also, what happens as tutors gain more experience in the writing center? Do they gain confidence in writing too? Lastly, is it always necessary that tutors gain self-efficacy? Could losing self-efficacy in an effort to learn something new be useful? While these are important questions, to date, there exists no empirical work on tutors' writing and tutoring self-efficacies to answer them or to explore the relationship between these concepts.

To develop insights into the above-mentioned questions, we designed a study to examine the relationship between tutors' writing and tutoring self-efficacies. By investigating this relationship, we can also gain deeper understanding of tutoring's long-term impact on tutors. For instance, if writing self-efficacy impacts learning transfer from composition courses, writing self-efficacy may also impact tutors' ability to transfer knowledge gained from staff meetings to sessions, and from tutoring in the writing center to other professional and personal contexts. If these types of transfers are possible, WCAs could use information regarding tutors' writing self-efficacies when educating and mentoring tutors.

Our study included both quantitative and qualitative elements. This chapter will focus on the qualitative part of our inquiry. Though we share relevant contextual results from the quantitative portion of the study below, an in-depth description of the quantitative part can be found in our article in Praxis: A Writing Center Journal (Powell and Hixson-Bowles). In what follows, we first discuss our methodology. We then provide in-depth descriptions of our results based on each tutor's interview. Finally, we offer suggestions for tutor education based on these results.

Exploring the Relationship between Self-Efficacies in Writing and Tutoring

To discover more information regarding tutors' self-efficacies in writing and tutoring, we first administered the Tutoring Writing and Academic Writing Self-Efficacy Scale (TWAWSES), which we adapted from Katherine Schmidt and Joel Alexander's Post Secondary Writerly Self-Efficacy Scale as well as Shaun White's Perceived Self-Efficacy Survey instrument for measuring self-efficacy in tutoring writing (Powell and Hixson-Bowles). As we discuss in our Praxis article, 146 tutors from higher education institutions around the world completed the survey. From this data, we learned:

- Tutors reported fairly high levels of self-efficacy in writing and tutoring (means fell between 80-100 on a scale of 0-100).

- Tutors' writing and tutoring self-efficacy scores correlated strongly (r=.815 and p=.001 using Spearman-Rho tests of correlation), indicating that tutors with higher tutoring self-efficacy also reported higher writing self-efficacy.

From these survey results, we confirmed that there is a statistically significant relationship between tutors' writing and tutoring self-efficacies. What these results do not tell us, however, is why tutors' writing and tutoring self-efficacies correlate. Is it because tutoring makes tutors better writers? Or is it because WCAs consistently hire tutors with high levels of self-efficacy in writing to begin with? Perhaps a bit of both—or something else entirely. While our survey results represent a broad view of tutors' writing and tutoring self-efficacies, we found ourselves wanting more nuanced answers to our questions concerning how tutors perceive the relationship between these self-efficacies.

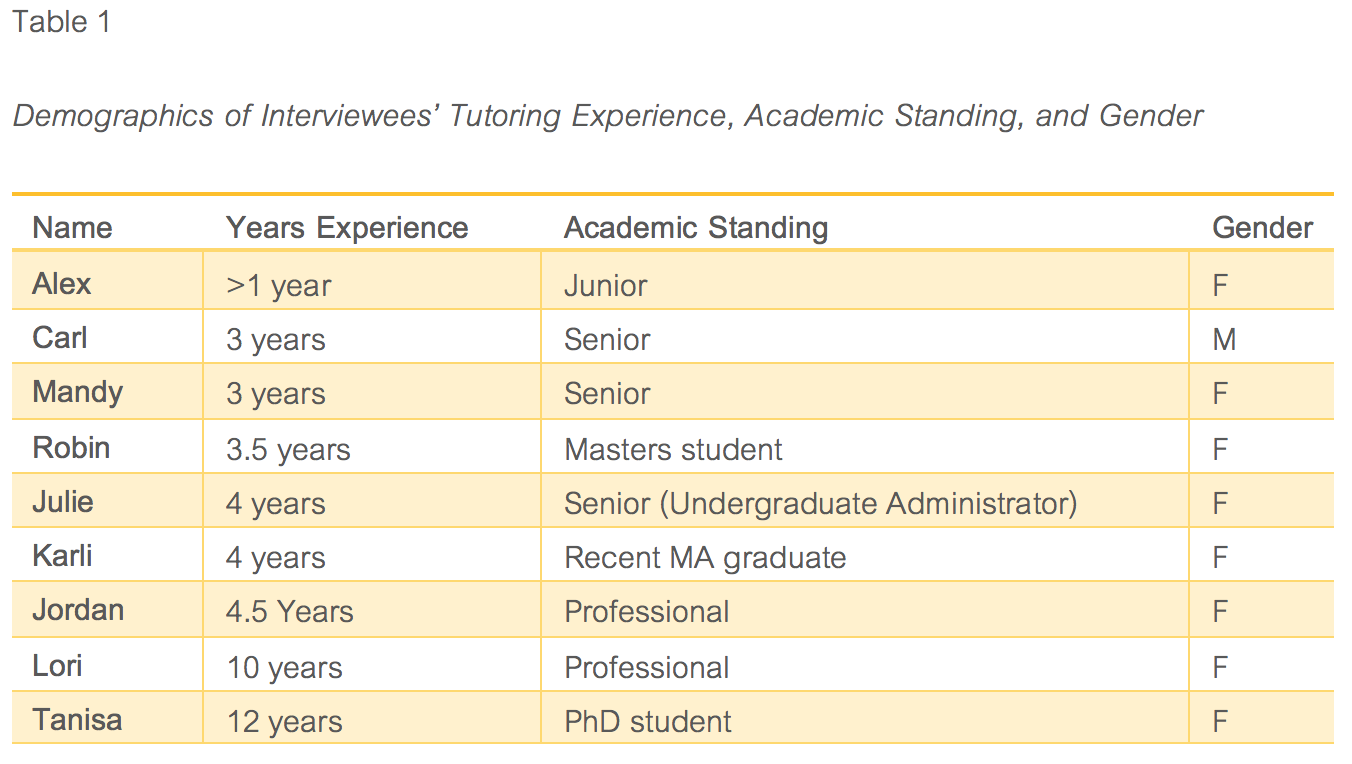

For this, we contacted the 58 participants who had indicated on the survey that they would be willing to be interviewed. From this group, ten responded, signed additional consent forms, and scheduled a time to meet with us. Nine of the interviews were used in data analysis (the audio quality of one recording was too poor to accurately transcribe). Most participants were experienced female tutors (see Table 1). All participants' names have been replaced with pseudonyms.

We conducted interviews over the course of 4 weeks in November and December of 2016. All interviews were conducted via Skype and/or over the phone, based on each tutor's preference, and were recorded using a Skype recorder and/or voice memo app. Interviews lasted approximately 20-30 minutes. Each tutor was asked the same set of questions (see Figure 1), which were originally developed alongside the survey questions. The interview questions were designed to prompt tutors to consider their self-efficacy from different perspectives. For instance, questions 3 through 6 ask about specific moments when the tutor felt confident or not confident in tutoring and writing. However, we also asked tutors to reflect on benefits they have received from their tutoring experiences (question 9). Ultimately, we found that asking tutors to conceptualize self-efficacy from a variety of perspectives induced tutors to give more nuanced and varied descriptions of their self-efficacies in writing and tutoring.

- How long have you been a tutor?

- Is this the first place you have tutored?

- What encouraged you to apply to be a writing tutor?

- Is the job what you initially expected? How is it similar? How is it different?

- Tell us about a time when you felt confident tutoring.

- Tell us about a time when you did not feel confident tutoring.

- Tell us about a time when you felt confident writing.

- Tell us about a time when you didn't feel confident writing.

- Do you think that there is a relationship between yourself as a writer and yourself as a tutor? If so, what is the nature of that relationship?

- Do you think that tutoring has made you a more confident or less confident writer? Why?

- What other benefits has tutoring given you?

- Is there anything else about yourself as a tutor that you want to tell us: things you do well? Things you still need to work on?

- Is there anything else about yourself as a writer that you want to tell us: things you do well? Things you still need to work on?

Figure 1. Self-efficacy questions posed to tutors who volunteered to participate in a recorded interview.

Following the interviews, we adapted Peter Smagorinsky's collaborative coding technique to code the transcripts. Smagorinsky, a proponent of more transparent methodology descriptions, developed a collaborative coding method which surpasses traditional standards of intercoder reliability. In other words, rather than all coders coding a small sample of the data and aiming for at least 80% code recognition and application, Smagorinsky codes alongside his fellow coders (usually graduate students). Each piece of data is discussed and codes are collaboratively generated, recognized, and applied. We met three separate times to collaboratively code two of nine transcripts. In these meetings, we tracked both agreement in code recognition and agreement in code application. Our averages reached 91% agreement in code recognition and 93% agreement in code application. The remaining transcripts were divided between us. When we had doubts or questions about our independently-coded transcripts, we met to discuss before making a coding decision.

As we coded, we examined code frequencies to determine patterns and anomalies across interviews. While we found that codes such as knowledge of tutee co-occurred with writing tutoring self-efficacy, and that disciplinary writing co-occurred with writing self-efficacy, what was most interesting to us was the way in which tutors described the relationship between their self-efficacy in writing and in tutoring.

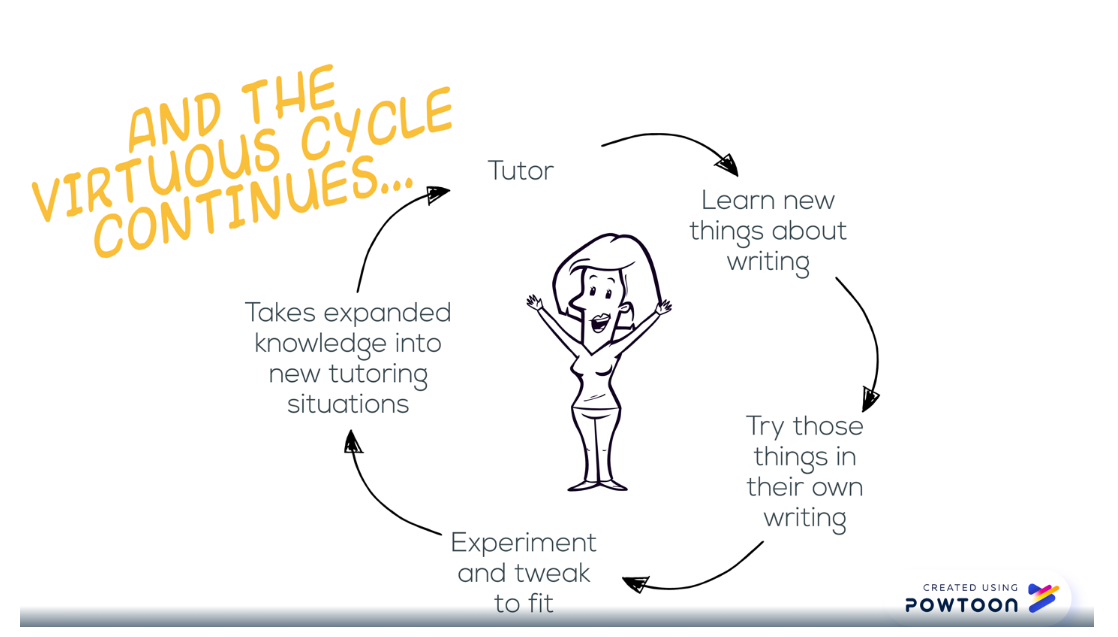

In the following section, we discuss three topics. First, we argue that the relationship between tutoring and writing is a virtuous cycle, meaning that a tutor's self-efficacy in tutoring and writing inform each other in positive ways. Second, we interrogate the role of self-efficacy in this cycle. Third, we demonstrate the complex nature of how a tutor's self-efficacy evolves in writing and tutoring.

Tutoring and Writing: A Virtuous Cycle

Nearly every tutor adamantly agreed that there was a relationship between their writerly and tutoring selves. This relationship was often described as a cycle. Mandy (Senior, 3 years, see Table 1) summarized the relationship well:

It's a constant cycle of tutoring and writing [that] makes me a better writer and...writing better improves my tutoring skills...the more I tutor, the more I see things that other writers do really well, and I kind of want to use for myself.

Though she doesn't name it as such, we recognize the cycle Mandy and other tutors described as a virtuous cycle, by which we mean that tutors' experiences with writing generate growth in tutoring and vice versa. At the heart of her tutoring knowledgebase is, of course, this tutor's writing experiences (Nowacek and Hughes). Therefore, a key part of the relationship between tutoring and writing is tutors' growth via writing experiences. Lori (Professional, 10 years) helps illustrate this point. Like Mandy and many tutors, Lori is fundamentally curious about writing when she tutors. She mines tutoring sessions to learn what works for different people. She stated,

One of the reasons that I love [tutoring] is you're both finding out new things and how people go about researching and all the different ways people make those choices and it's worked. Like how do people approach it? To figure out how people who are very detail-oriented and organized and linear...do these things. People who are completely not linear and organized in that way and how they still make some things work. The different place[s] people go for research, the different ways they sort of attack pre-writing [or] revision strategies. You get to learn about tools people are using so you can use them later.

Lori and Mandy both demonstrate that for some tutors, if not most, there is a conscious awareness of learning new strategies and techniques for writing as they tutor. Later in her interview, Lori noted, "there are all kinds of ways to get to that final product," which also illustrates the broad view of writing that tutors build as they gain experience tutoring.

Lori and Mandy exemplify the first few steps of the virtuous cycle of tutoring and writing (see video). These interviews revealed a pattern in tutors' experiences of the relationship between tutoring and writing.

| Figure 2. The Virtuous Cycle of Tutoring and Writing. |

The virtuous cycle, depicted in Figure 3 below, illustrates a new tutor starting their position with the writing knowledge they've collected thus far in their education. After tutoring for a while, the tutor witnesses new techniques and approaches to writing. Though the video depicts this new information coming from a writer the tutor is tutoring, evidence from our interviews suggest that the growth in writing knowledge can also come from other tutors and tutor education (expanded upon in the following section). In the next step of the virtuous cycle, the tutor begins to apply their newfound writing knowledge to their own writing. Sometimes, the tutor will need to adapt this new knowledge to fit it to their context, thus expanding on the new knowledge they've gathered. Finally, the tutor tutors again—but now equipped with new writing information/tools/techniques—and so the virtuous cycle continues.

|

| Figure 3. The Virtuous Cycle of Tutoring and Writing. Visual diagram created by the authors. |

In answering our question concerning the relationship between tutoring and writing, Karli (Recent MA graduate, 4 years) exemplifies how a tutor might weave their writerly self into the act of tutoring:

I think that my impression of tutoring is very much just sitting down with someone and [them] telling me what's going on here. How can I help you? And then you design the experience. I mean, my experience as a writer certainly plays a large part in that, to say, 'okay, here are some things that I do to address the situation. Here are some resources that I rely on sometimes.' If I can't help them through it, and I can't answer their question right away, I say 'there's a tutor over here that I talk to about this all the time. Let's go ask them really quickly.' So I feel like I draw on the resources that I use as a writer directly when I'm tutoring all the time. Because I try to come across as a writer to them....We are all writers here, and so let's see what we can get done with the knowledge that we bring to the table.

For Karli, her writerly self is absolutely centered in her tutoring persona. As her response illustrates, in tutorials, she relies on her (as well as her fellow tutors') knowledge of writing and experiences as a writer. In this case, she models positive writerly behavior (i.e. utilizing resources, knowing the limits of her knowledge) in tutorials. Like Karli, Carl (Senior, 3 years) centers himself as a writer squarely in his tutoring persona:

As you learn how to write more, and just refine your writing more, you are able to express that in tutoring sessions better. Yeah, you know, the relationship is definitely there, if it's even a relationship at all, and not just the same thing. I'm not even sure I can separate the two.

Carl takes this concept a step further by questioning the nature of the question itself. For Carl, the line between tutoring and writing is very thin, if it exists at all. We can see a bit of this sentiment in Karli's perspective as well. When she tutors, she forefronts her identity as a writer.

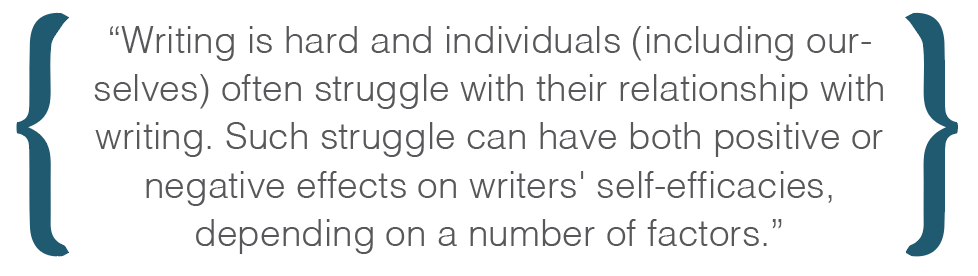

In some ways, as tutor educators, we are pleased to hear perspectives like these from tutors. One vision of the ideal writing center is a slightly utopic place where writers get help from other writers, and no one can really tell who is tutoring whom because everyone is learning from everyone. It's a dreamy idea, and we are certainly lured by such visions. But then we remember that writing is hard and individuals (including ourselves) often struggle with their relationship with writing. Such struggle can have both positive or negative effects on writers' self-efficacies, depending on a number of factors. The question, then, that we turn to next is how do different experiences of writing self-efficacy impact tutors and their tutoring self-efficacy?

In some ways, as tutor educators, we are pleased to hear perspectives like these from tutors. One vision of the ideal writing center is a slightly utopic place where writers get help from other writers, and no one can really tell who is tutoring whom because everyone is learning from everyone. It's a dreamy idea, and we are certainly lured by such visions. But then we remember that writing is hard and individuals (including ourselves) often struggle with their relationship with writing. Such struggle can have both positive or negative effects on writers' self-efficacies, depending on a number of factors. The question, then, that we turn to next is how do different experiences of writing self-efficacy impact tutors and their tutoring self-efficacy?

The Role of Self-Efficacy in the Virtuous Cycle

To illustrate the role of self-efficacy in the virtuous cycle of tutoring and writing, we first discuss Julie (Senior [Undergraduate Administrator], 4 years). Julie described a moment of cognitive dissonance she experienced when one of her tutor education meetings covered grammar, standard academic English, and other varieties of English. Julie mentioned that she "grew up with an academic" and, therefore, "talk[s] like they do." Though she enjoys the access this experience has given her to connect with her professors quickly, after this tutor education meeting, Julie realized that her privilege extended to how her papers have been graded. She said,

I actually felt less confident because I was thinking 'okay, this stuff that people have been using to tell me I'm good at writing all along is not real or the same. And perhaps I'm perpetuating systematic racism, or different problems, if I'm doing what I've been taught to do.' So that was kind of a blow to my confidence.

Julie worried that the knowledge and skills in language she thought she had was simply a result of a system that privileges her class and whiteness. Furthermore, she worried that the advice she had been giving to multilingual writers or speakers of African-American Vernacular English had further marginalized them, as she originally had assumed standard academic English was always correct and always appropriate.

For a moment, Julie experienced lower self-efficacy in both tutoring and writing. And while she did push past it—we will discuss the 'how' in a moment—first let us emphasize the importance of this moment of low self-efficacy. Much of the literature on self-efficacy in writing education stresses the importance of writers needing high self-efficacy to perform (Ekholm et al.; Pajares; Parajes & Johnson; Williams & Takaku). And while we agree that building self-efficacy is important in decreasing apprehension and enabling transfer, we argue that simply having high self-efficacy in writing and/or tutoring is not sufficient, and is even something WCAs should be wary of (an idea we'll expand on in the "Tutor Education Strategies" section). Moments like the one that Julie experienced are essential to growth. Her low self-efficacy came out of new ideas that disrupted her assumptions regarding writing, language, and her own mastery of both. In light of her newfound understanding of language, race, and culture, Julie felt that the confidence she had in her ability to navigate English prior to this particular lesson in tutor education was not founded in linguistic research or composition scholarship; rather, she felt it was founded in her privilege and intuition. Though it is likely that Julie's writing abilities were actually constructed by a complex web of privilege and linguistic and composition praxis, the realities are less important to our point than how she perceived her abilities in writing and tutoring.

Julie moved through her low self-efficacy, rebuilding her self-efficacy in writing and tutoring through careful reflection, practice, and additional education. As part of her reflection, Julie started recognizing moments others were code switching when she didn't have to. She contemplated the mental and emotional energy code switching requires. Transferring this knowledge and awareness of privilege to different aspects of her life, Julie recognized religious privilege playing out in discussions in her constitutional law class. These details exemplify the ways in which Julie thought and reflected on the lessons taught in her tutor education course.

Julie also noted in her interview that she regained confidence by doing a lot of tutoring. Practicing tutoring exposed her to a wider variety of learners, disciplines, and techniques. She said, "Getting more experience tutoring has made me feel more confident with wait times, or sitting back and trusting that we'll get there, and that it's not a problem if we don't talk about every error in your paper." Becoming comfortable with the new knowledge she gathered in her tutor education took time. To a degree, Julie had to rebuild her worldview. Fortunately, the very meeting that caused the cognitive dissonance also, as Julie put it, "help[ed] me build a few concepts of what good writing is." Her abilities to recognize, reflect on, and take action to learn what she lacked all contributed to the now justified high self-efficacy in tutoring and writing that she rebuilt:

Julie also noted in her interview that she regained confidence by doing a lot of tutoring. Practicing tutoring exposed her to a wider variety of learners, disciplines, and techniques. She said, "Getting more experience tutoring has made me feel more confident with wait times, or sitting back and trusting that we'll get there, and that it's not a problem if we don't talk about every error in your paper." Becoming comfortable with the new knowledge she gathered in her tutor education took time. To a degree, Julie had to rebuild her worldview. Fortunately, the very meeting that caused the cognitive dissonance also, as Julie put it, "help[ed] me build a few concepts of what good writing is." Her abilities to recognize, reflect on, and take action to learn what she lacked all contributed to the now justified high self-efficacy in tutoring and writing that she rebuilt:

I came to understand writing more theoretically and understand the concepts of genre and audience better. I think I also felt more confident because gut reactions I had like, 'Oh, I don't think that sounds quite right,' can be stated as, 'There's redundancy there,' or 'it's not parallel,' or even '[using complicated words is] ignoring the audience's needs.'

In other words, after a tutor training session shook her confidence in both her writing and tutoring, Julie allowed herself to be uncomfortable in order to learn more. By doing so, she rebuilt her self-efficacy through reflection, practice, and further educating herself on privilege and language. Julie summed up her journey by saying, "Having that language to describe writing, having the training course every semester, being constantly reflecting on my writing, all of those things, I think helped increase my confidence as a writer."

The Messy Process of an Evolving Self-Efficacy

Julie exemplifies a productive ebb and flow of self-efficacy and learning. That being said, she was clearly discussing a moment of evolution in her thinking and in her self-efficacy that had already occurred. Given the educational environment we exist in, WCAs, lead tutors, and others in mentoring roles will likely observe tutors in the thick of evolving self-efficacies. Though we focus solely on self-efficacy in tutoring and writing in this study, it is important to keep in mind that self-efficacy does not exist in a vacuum. Self-efficacy is likely influenced by (and influences) other dispositions, as Neil Baird and Bradley Dilger's recent study suggests. This research in conversation with Dana Driscoll and Roger Powell's study on emotional states, traits, and dispositions also suggests that self-efficacy likely interacts with students' emotional dispositions as well. Given that transfer research has examined more broadly the role identities play in students' writing transfer (see Elizabeth Wardle and Nicolette Mercer Clement and Stacey M. Cozart et al.), and given the ways people of different genders/sexual orientations/races/etc. are socialized to move through the world, it also seems likely that self-efficacy is affected by identities. However, not enough is yet known about how other dispositions, emotions, identities, or personalities interact with or influence self-efficacy in tutoring and writing. Though we know the broader context certainly adds complexities to the messy process of an evolving self-efficacy, our goal in this section is to demonstrate one way self-efficacy may manifest whilst in the process of evolving.

In our interviews, we witnessed one tutor working through cognitive dissonance affecting his self-efficacy in writing and tutoring. Carl (Senior, 3 years) stood out to us for a number of reasons, including that his responses had the highest number of high self-efficacy codes in both tutoring and writing. The more we studied Carl's answers, the more intriguing his relationship with self-efficacy became. Given the complexities we witnessed in this moment of Carl's evolving self-efficacy, as well as the likelihood that many tutors our readers will encounter will also be experiencing such nuances, we will spend a bit more time on his case. In what follows, we discuss three of our primary observations regarding factors influencing Carl's tutoring and writing self-efficacies: (a) his perception of writers' confidence in his tutoring abilities and writing expertise, (b) his own perception of his writing abilities, and (c) his perception of performing confidence, by which we mean intentionally projecting confidence through language, body language, and behavior.

Tutors' perceptions of writers' confidence in their abilities and writing expertise. Carl's perception of the writer's confidence in him played an important role in how confident he felt tutoring. This theme came up often in his transcript. Three statements in particular support this conclusion:

I think it has more to do with how you present yourself than the self-internalization of [confidence]... .I always think, as a tutor, you have to be just a little bit cocky in some sessions or else the student won't believe you. You know, they won't buy into it.

But you know, it's one of those things that the more time you spend tutoring, the more comfortable you get with doing it...it's a weird place to be--in a peer-to-peer tutor position, right? It's strange, because I work with students who are older than me or who are taking advanced classes that I will never have any comprehension of, but they're looking to me for guidance [with] writing. And, you know, when the student trusts you, you can feel confident, but when the student's unsure in themselves, unsure of their paper and they're even unsure of me as a tutor, that's when the confidence kind of drops.

...because it's peer-to-peer tutoring, a lot of the times the confidence that I feel in sessions comes from the person I'm tutoring. If he or she is receptive, and if he or she is engaged, and is actually talking with me and not just expecting me to spoon-feed them the answers, that's when it's easiest to feel confident in what we're doing, that's when it's easiest to feel confident in my abilities as a tutor. It's when someone is engaged with me, someone is actually invested in the tutoring experience and not just there because a paper is due in an hour and they need their commas fixed.

Carl is highly aware of his position as peer. These responses suggest that Carl's confidence in tutoring somewhat relies on the writers' confidence in him as a tutor as well as writers engaging in the sessions by assuming the peer collaborator role alongside him. Carl also hints at a struggle with self-efficacy when the writer is more advanced or less engaged than he is. Whether or not a writer actually exhibits confidence or lack thereof in Carl, his perception of the writer's confidence in him influences his self-efficacy in tutoring.

Tutors' perceptions of their own writing abilities. Of course, there is another important contributor to Carl's tutoring self-efficacy—his writing abilities. The stronger his self-efficacy in writing, the stronger his self-efficacy in tutoring. Remember, it was Carl who said, "as you learn how to write...you are able to express that in tutoring sessions better." He expanded on that sentiment:

It's like a loop, right, where if I go to a session and a session goes well then I have confidence as a tutor, and I'll say "Okay, I know what I'm doing as a tutor, I know what I'm doing as a writer," especially if I write well it makes me confident in my writing, which makes me more confident to go into the session and it just keeps moving and moving and moving.

This statement is interesting for a number of reasons. It seems, on the surface, to exemplify the virtuous cycle of tutoring and writing. Upon closer examination, though, this response makes it seem as though Carl's self-efficacy in tutoring is subject to change after every session he takes. Though he refers to positive experiences, in the context of Carl's entire interview, we can also imagine that the inverse may be true—Carl might have a bad tutoring session which could negatively affect his writing self-efficacy, which could negatively affect his tutoring self-efficacy. While we expect individual sessions to have some influence on tutors' self-efficacy in tutoring, if a tutor's self-efficacy is spiking or dipping dramatically after different sessions, that could indicate that the tutor actually has low self-efficacy and needs to work to build their confidence with targeted strategies (see "Tutor Education Strategies" below). Carl's response is also interesting in light of his previous statements about feeling confident when writers show confidence in him. If Carl has such high writing self-efficacy and that actually feeds his tutoring self-efficacy, then why does he also seek the external validation of the writers he meets with? However, when answering a question regarding a time he felt confident writing, Carl stated,

This statement is interesting for a number of reasons. It seems, on the surface, to exemplify the virtuous cycle of tutoring and writing. Upon closer examination, though, this response makes it seem as though Carl's self-efficacy in tutoring is subject to change after every session he takes. Though he refers to positive experiences, in the context of Carl's entire interview, we can also imagine that the inverse may be true—Carl might have a bad tutoring session which could negatively affect his writing self-efficacy, which could negatively affect his tutoring self-efficacy. While we expect individual sessions to have some influence on tutors' self-efficacy in tutoring, if a tutor's self-efficacy is spiking or dipping dramatically after different sessions, that could indicate that the tutor actually has low self-efficacy and needs to work to build their confidence with targeted strategies (see "Tutor Education Strategies" below). Carl's response is also interesting in light of his previous statements about feeling confident when writers show confidence in him. If Carl has such high writing self-efficacy and that actually feeds his tutoring self-efficacy, then why does he also seek the external validation of the writers he meets with? However, when answering a question regarding a time he felt confident writing, Carl stated,

I think I'm a pretty damn good writer, and it is not often that I am not confident in my writing. I'm not always necessarily super thrilled with what I put out. I'm not always super proud of it, but it is not very often that I have any doubts about my ability to...write something.

Although he projects confidence, we suspect that perhaps Carl's writing self-efficacy isn't quite as high as it appears on the surface. While, after some discussion, we were able to ascertain that there are some assignments/genres and writing tasks that he felt less confident in, Carl's message was clear: he did not struggle with writing self-efficacy.

Tutors' perceptions of performing confidence. Throughout Carl's interview, we noticed that confidence and cockiness were sometimes used interchangeably. To clarify Carl's perspective, we asked him where he thinks the line between confidence and cockiness is. In response, Carl said,

I think it has more to do with how you present yourself than the self-internalization of it... .I always think, as a tutor, you have to be just a little bit cocky in some sessions or else the student won't believe you. You know, they won't buy into it...I very strongly, very, very, very strongly believe that, you know, practicing intentional empathy with students and leveling with them and just being honest with them and transparent, but I also think you gotta, just kinda gotta pop your chest out a little bit, like, "You know what? Yeah, I'm working here for a reason. I know what I'm doing. Just let me help you."

As part of his response, he emphasized the importance of being honest with writers. Though he does not name what specifically he feels he needs to be honest about, we surmise that Carl is talking about being honest about his level of skills and abilities as a writer. While he does not intend to mislead writers, he also thinks tutors need to display confidence (or cockiness?) in sessions ("just kinda gotta pop your chest out a little bit..."). Carl continued,

I think you need to be just a little bit over that line [between confidence and cocky] as a tutor, but I think that being cocky in anything is a dangerous position because when you get to that point, you stop feeling like you have to grow, and that's where you can run into some trouble.

Carl's use of the word "cocky" seems to shift as he speaks. At first, it appears that Carl feels "cocky" in moments when he projects more confidence than he feels in order to gain the trust and confidence of the writer he's working with ("as a tutor, you have to be just a little bit cocky in some sessions..."). It is possible that what Carl describes as "cocky" at the beginning of his statement is a response to imposter syndrome. It is easy to imagine that Carl's intent is to communicate that a "fake it 'till you make it'" mentality is sometimes necessary in tutoring. However, the meaning shifts when he considers the downfall of being "cocky." He seems to reimagine cockiness as internalizing false confidence or too much confidence and warns tutors not to close themselves off to learning new things.

While we agree with Carl's conclusion that too much confidence can lead to a stagnation in growth, we can't help but feel suspicion towards Carl's confidence. One thing feeding our suspicion is a quote from Karli's (Recent MA graduate, 4 years) interview:

I think that sometimes when people are starting out tutoring, they feel like they need to put on this sort of act that they know more than they actually do or that they have all this crazy detailed knowledge about whatever topic and that's something that is just unrealistic.

Though Carl is definitely not a new tutor, his position that tutors sometimes have to exaggerate what they know to win the writer's confidence feels eerily similar to the behavior that Karli describes. Karli may be correct that performing confidence is behavior found primarily in new tutors, but it is certainly not limited to new tutors. Of course, we can't know definitively from one interview the intricacies of Carl's self-efficacy in tutoring, writing, and the way he experiences the relationship between the two. At the same time, the window provided by his interview suggests the possibility that other tutors may experience similar tensions in their self-efficacies in writing and tutoring. More research needs to be done to learn how and why tutors like Carl feel pressure to perform confidence while tutoring—and, perhaps, how the distraction of that pressure to perform/be confident impacts tutors' interactions with writers.

Summarizing our Findings

At the beginning of our investigation, we wanted to better understand the relationship between tutors' self-efficacies in writing and tutoring. In the quantitative portion of this study, we found a statistically significant correlation between tutors' self-efficacy in writing and in tutoring. On the surface, this looked great: it suggested that self-efficacies in writing and tutoring develop alongside one another. The survey data also demonstrated that, on average, tutors have pretty high self-efficacy in both tutoring and writing. Again, this was encouraging, as literature on learning writing states that high self-efficacy facilitates transfer and combats writing apprehension.

The qualitative findings deepened our understanding of the correlation between tutors' writing and tutoring self-efficacies. We learned that a major contributing factor to this relationship is the virtuous cycle tutors experience between tutoring and writing. Self-efficacy plays an important role in this cycle and thus in tutors' development as both tutors and writers. In this study, tutors demonstrated an awareness of gaining new writing strategies and concepts through their tutoring experiences, adapting those strategies/concepts into their own writing practice, and then sharing the new knowledge they had gained with writers they tutor. In this way, tutors described centering their writerly selves in their tutoring personas. These findings suggest that tutors' self-efficacies in tutoring and writing can either strengthen the productive relationship between tutoring and writing or weaken it.

The qualitative findings deepened our understanding of the correlation between tutors' writing and tutoring self-efficacies. We learned that a major contributing factor to this relationship is the virtuous cycle tutors experience between tutoring and writing. Self-efficacy plays an important role in this cycle and thus in tutors' development as both tutors and writers. In this study, tutors demonstrated an awareness of gaining new writing strategies and concepts through their tutoring experiences, adapting those strategies/concepts into their own writing practice, and then sharing the new knowledge they had gained with writers they tutor. In this way, tutors described centering their writerly selves in their tutoring personas. These findings suggest that tutors' self-efficacies in tutoring and writing can either strengthen the productive relationship between tutoring and writing or weaken it.

The qualitative findings also provided more nuance in our understanding of self-efficacy in tutoring and writing. Though more research is needed, our findings suggest that the quality of self-efficacy matters, perhaps more, than the quantity of self-efficacy. For instance, Julie's (Senior [Undergraduate Administrator], 4 years) process of temporarily "losing" writing self-efficacy and rebuilding it after discovering the problematic nature of Standard Academic English for minority communities demonstrates how self-efficacy can develop in quality as well as in quantity. Therefore, learning something new may temporarily decrease a tutor's self-efficacy, but can ultimately lead to higher quality self-efficacy if the tutor continues their education through reflection and practice.

When working to develop tutors' self-efficacies in tutoring and writing, it's important to remember that tutors' growth in self-efficacy is a process—and can be a messy process, full of contradictions. Perhaps not surprising, given the peer-to-peer nature of writing center tutoring, Carl's experiences demonstrate that the tutors' perception of how writers perceive them, their abilities, and the tutorial may impact tutors' confidence both in the moment as well as in their overall development of tutoring self-efficacy. Most importantly, though, our study demonstrates that both high and low self-efficacy in writing and/or tutoring can be a sign of healthy growth and learning. In the next section, we offer some ideas for how to apply lessons we learned from our interviews to tutor education.

When working to develop tutors' self-efficacies in tutoring and writing, it's important to remember that tutors' growth in self-efficacy is a process—and can be a messy process, full of contradictions. Perhaps not surprising, given the peer-to-peer nature of writing center tutoring, Carl's experiences demonstrate that the tutors' perception of how writers perceive them, their abilities, and the tutorial may impact tutors' confidence both in the moment as well as in their overall development of tutoring self-efficacy. Most importantly, though, our study demonstrates that both high and low self-efficacy in writing and/or tutoring can be a sign of healthy growth and learning. In the next section, we offer some ideas for how to apply lessons we learned from our interviews to tutor education.

Tutor Education Strategies

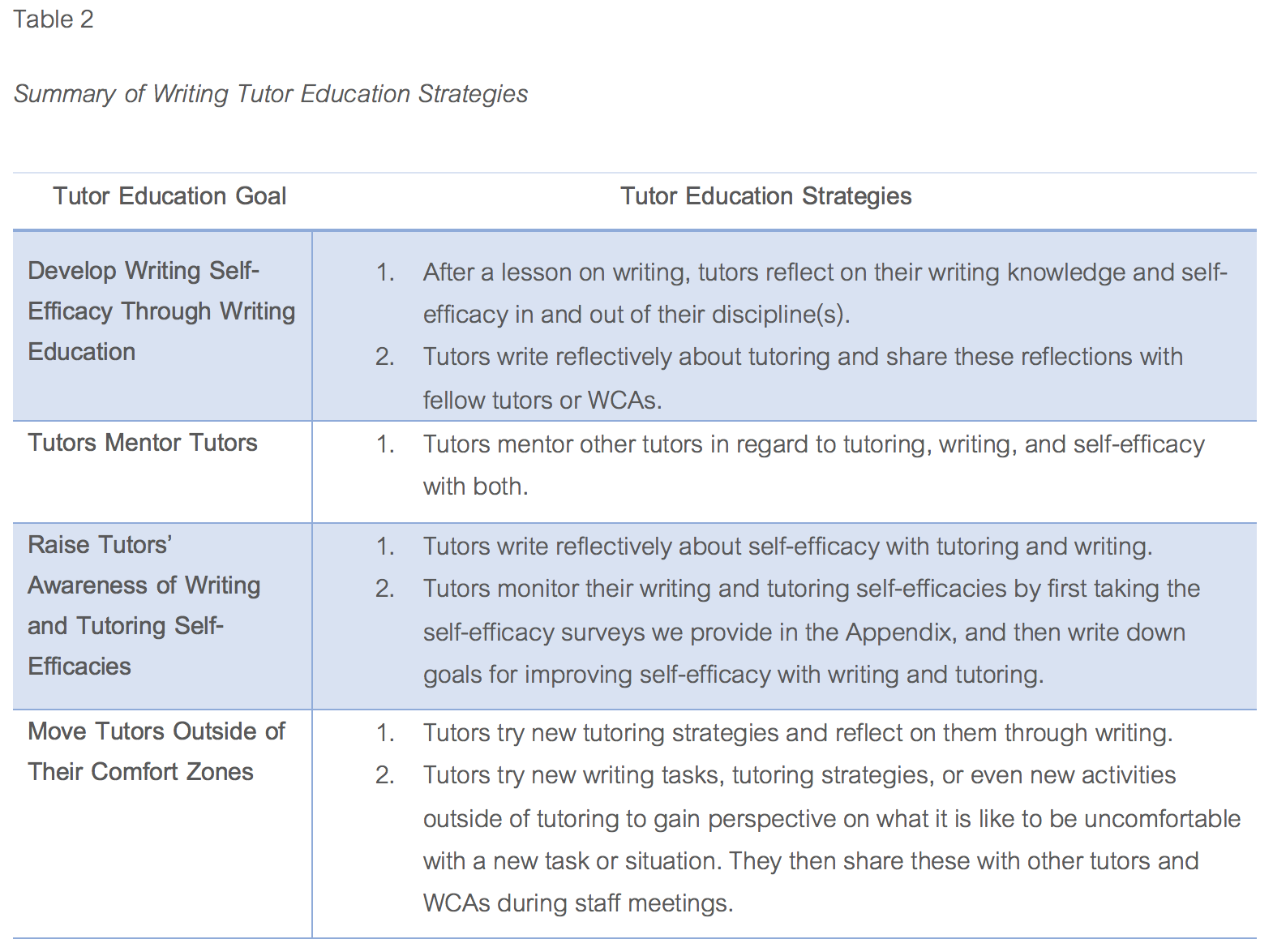

Based on our results, we recommend several tutor education goals and tutor education strategies (see Table 2) that WCAs can use to help tutors develop tutoring and writing self-efficacy. These strategies, many of which are similar to commonly practiced strategies (see Julia Bleakney's study in this collection), can work within and alongside existing tutor education practices. Table 2 offers a summary of the tutor education goals and brief examples of tutor education strategies; a more detailed explanation of how to implement these strategies follows.

Develop Writing Self-efficacy through Writing Education

Our first suggestion is to make writing education an integral part of tutor education by having tutors reflect on their writing self-efficacy. This reflection may come through writing reflectively about self-efficacy, talking about their writing with other tutors and WCAs, or some combination of the two. Many WCAs already include varied levels of writing education and reflective writing in their tutor education, so including reflective writing on self-efficacy can be easily adapted to existing education programs. For example, it is often a common practice to have an instructor visit the writing center in order to describe their expectations for an assignment and/or writing in their particular discipline. This is certainly a good way to teach tutors writing within the context of a particular class or discipline, but, if done every semester/year, returning tutors may consider these visits repetitive and dull. While we are not dismissing this practice, we suggest adding to it by having tutors discuss with fellow tutors and/or write reflectively on how this visit might help not only their tutoring, but their own writing. Furthermore, tutors can explicitly reflect on how confident they are with particular genres of writing presented in these instructor visits, write down goals for developing more confidence in writing and tutoring these genres, and then share these goals with fellow tutors and WCAs. Essentially, tutors can use the information they learn from visiting instructors to help them increase writing self-efficacy.

We also suggest that tutors take note of writing strategies they learn from their tutoring sessions (a point Lori [Professional, 10 years] brought up in her interview). Tutors can record these strategies and share them during a staff meeting or in a collective resource, which could be used in sessions or when writing on their own. We believe that encouraging tutors to actively reflect on the process of learning from other writers may contribute to building quality self-efficacy. Additionally, the process of collecting and sharing knowledge in this way demonstrates to newer tutors that, to be prepared to tutor, they do not need to know everything or act as though they know everything. Instead, new tutors should know that it is okay to lack confidence with writing and work towards gaining that confidence in healthy ways.1 Experienced tutors could help reinforce this point and share ways they have lacked confidence and then tried to regain confidence. Overall, tutors shouldn't feel the need to perform confidence to the degree we heard in Carl's interview.

Ultimately, investing in tutors' writing education not only helps them develop self-efficacy in writing, but it also feeds into the virtuous cycle they experience between tutoring and writing. Addressing their growth as writers head-on introduces more intentionality into the cycle. WCAs should speak transparently regarding the benefits tutoring and tutor education will have on tutors' growth as writers regardless of their incoming writing and tutoring experiences.

Tutors Mentor Tutors

Recent scholarship (including Pittock and Cirillo-McCarthy's chapter in this collection), has discussed the impact tutor-to-tutor mentorship can have on tutors' growth in their tutoring abilities. A story from one of our interviewees illustrates this possibility well. Mandy (Senior, 3 years) was quickly losing confidence in her tutoring after working with a student who refused to engage in his sessions and yet continued to schedule appointments. To find solutions to this dilemma, Mandy sought out help by talking with other tutors. In these conversations, Mandy realized, "Clearly he's coming back in a couple times a week for a reason, and it's not because he wants to waste his time." As a result, Mandy and her fellow tutors decided to try a new strategy:

...checking in every 10 minutes of the session. Say, "Hey, are you finding this helpful? Where would you like to spend the 20 minutes or whatever that's left. How can we best work with you?" And just leaving that open-ended and admitting I don't really know what you want from me yet, but we can figure that out.

In this example, Mandy models actively seeking ways to increase her tutoring self-efficacy by drawing on the staff's collective experience and knowledge. While she may not have all the solutions, Mandy could make an excellent mentor to a new tutor also struggling to negotiate an agenda with a writer. Mandy's experience also illustrates how identifying a situation or task that is chipping away at self-efficacy can lead to productive, collaborative, and intentional growth. Therefore, discussing benefits of seeking advice from fellow tutors during tutor education programs can help tutors grow in productive ways and build writing and tutoring self-efficacy.

Raise Tutors' Awareness of Writing and Tutoring Self-Efficacies

Raising tutors' awareness of their self-efficacies in tutoring and writing as a strategy for tutor education can be beneficial to the long-term growth of tutors and students. One way to raise awareness is by having tutors complete the TWAWSES we discussed earlier in this article (see Appendix) to understand their tutoring and writing self-efficacies. This survey could be administered at the beginning and end of a semester/year. The self-efficacy scales serve as a starting point for understanding self-efficacies in tutoring and writing. These scales can incite conversations in class or staff meetings centered on the nuances of self-efficacy. Tutors can also use these scales as a prompt to write reflectively throughout the semester. Writing reflectively about their sessions, their own writing projects, and their self-efficacy can help raise tutors' awareness of their writing and tutoring development.

For administrators, there is an added benefit to tracking tutors' self-efficacy and growth in tutoring and writing in this way: assessment. As Elisabeth H. Buck argues in her chapter, "From CRLA to For-Credit Course: The New Director's Guide to Assessing Tutor Education," low-stakes assessment of tutor education can be advantageous. Though self-efficacy can be tricky to measure, the writing and tutoring self-efficacy scales offer one way of measuring tutors' development (just be sure not to get caught in the "high self-efficacy or bust" trap). Knowing where tutors' self-efficacy scores are at the beginning and end of a semester/year can provide insights into the challenges they've taken on and the skills they've focused on, both of which can influence the direction ongoing tutor education needs to take. For both tutor education and assessment, the scales can also be modified to better fit local needs. For instance, Kelsey adapted the measurements from a 0-100 to a 0-10 scale to distance students from a traditional grading scale. WCAs could also choose to tweak or add different tasks to the scales. Either way, helping tutors become more aware of their self-efficacies in writing and tutoring also has the added benefit of helping administrators assess tutors' development and tutor education.

Move Tutors Outside of Their Comfort Zones

To reinforce efforts to include more explicit writing education and to raise tutors' awareness of their tutoring and writing self-efficacies, we also suggest that tutors should occasionally move outside of their comfort zones. This final strategy of developing tutors' self-efficacy can sometimes mean increasing their self-efficacy through uncomfortable tutoring and writing tasks. Furthermore, this perspective of being uncomfortable with one's writing is something that many students bring to writing center sessions. We again consider Carl (Senior, 3 years) because he seemed to be lacking confidence in himself, and he overcompensated by acting "cocky" or showing unfounded self-efficacy. Tutors need to remember what it is like to lack confidence with writing or other new tasks to develop, as Carl puts it, "intentional empathy," with students who come to our centers.

First, we suggest strategies through some traditional practices with tutor training—writing reflectively, role-playing, and discussions. Reflective writing prompts could include asking tutors to consider their self-efficacy with particular tutoring tasks—such as the way they build rapport and relationships with writers—and monitoring their self-efficacy with this task over time. Do they lack confidence? Do they feel like they have too much? Or are they balanced on this task? Borrowing from Mary Pigliacelli's chapter, "Practitioner Action Research on Writing Center Tutor Training: Critical Discourse Analysis of Reflections on Video-recorded Sessions," another activity could use video recordings of sessions to prompt reflection. These reflections could explore strategies such as asking different types of questions to help students revise or build rapport. These types of strategies would help tutors break out of their routines and remember what it is like to feel uncomfortable. Tutors could write an end-of-the-semester reflection and make new goals for how they might address their self-efficacy with this task later on. Tutors might also roleplay how to handle difficult tutoring situations during staff meetings in order to practice strategies to develop their self-efficacy in such situations and then follow up by discussing these strategies in more depth.

In addition to traditional education strategies, tutors can try activities not related to tutoring to get them out of their comfort zones. We suggest this idea because there may be times when tutors feel they have a certain level of mastery with tutoring or with writing, especially when employed as professional tutors. While it is not a bad trait for tutors to feel confident, we argue that it is good for experienced tutors to remember the perspective of feeling uncomfortable, insecure, and new at something. This perspective is vital to successful tutoring because, as mentioned above, many students come to writing center sessions uncomfortable with writing, especially first-year students who are facing college-level writing and academic standards for the first time. While the above activities would help with increasing tutors' self-efficacy with tutoring tasks—and have the potential to help tutors keep their practices new and fresh—having tutors try something radically new may be an especially productive way to get them out of their comfort zones and help them not only as tutors, but also as professionals. These new experiences could involve writing, tutoring, or something else; the important factor is simply that they be truly new.

We have implemented this suggestion with our tutor training and offer the following example to highlight how this can help with tutors' self-efficacy and professional growth. One tutor, whom we will call Jessica, pushed herself to do something that made her uncomfortable. Jessica was normally shy and didn't like speaking in front of others. One summer while working as a tutor in the writing center, Kelsey encouraged Jessica to work with Roger on a research project with the online writing center. Towards the end of the project, Kelsey and Roger encouraged Jessica to present what she learned from this project at a staff meeting. During this presentation, Jessica experienced stage fright and had to leave the room. After a few minutes and a few tears, she came back and delivered her presentation. Roger and Kelsey had debriefing meetings with her to brainstorm strategies to avoid stage fright in future presentations and overcome her fear of speaking in front of others. Jessica continued to practice her presentation skills in front of small groups and eventually gave a workshop to a class that came to the writing center. Jessica even developed enough self-efficacy to present in front of a crowded room at the Mid-Atlantic Writing Center Association Conference and did so without any (visible) stage fright. She is now attending graduate school and presenting her research at conferences within her discipline.

Sometimes the tutors who make up our centers are exceptional students who have excelled in writing for years. Having them try new writing experiences may or may not be successful, so finding a challenging task that will help them experience the perspective of being new, uncomfortable, and unsure is important. When tutors are reminded what it's like to be a novice, their self-efficacy may initially dip, but it will eventually rebuild on a stronger foundation, which makes tutors better suited to help students. Jordan (Professional, 4.5 years) and Julie (Senior [Undergraduate Administrator], 4 years) embraced cognitive dissonance by first reading scholarship that challenged their writing and tutoring assumptions, reflecting on what they learned, and practicing tutoring and writing with the new information. They are both excellent examples of the process we encourage here.

Conclusion

Based on our results, we find that tutors' writing and tutoring self-efficacies can be important to their growth and development as writers and tutors. Tutor education with self-efficacy in mind can work within and also extend prior tutor training practices such as roleplaying mock sessions, reflecting on tutoring practice, infusing writing education into tutor training, and mentoring other tutors.

To build on this framework with further research, we suggest follow-up studies with different methodologies to examine self-efficacy's impact on tutors' tutoring and writing. One suggestion would be to include observations: tutors could first take the TWAWSES to measure their self-efficacy in certain tutoring tasks; following this task, tutors with different levels of self-efficacy could be observed in sessions to see how they tutor. To determine "how tutors tutor" one could draw on Jo Mackiewicz & Isabelle Thompson's recent framework for tutoring strategies and see what strategies tutors with different levels of self-efficacy utilize. Researchers could then develop an instrument to measure the effectiveness of these tutoring strategies to determine the degree to which self-efficacy impacts tutoring. This instrument might allow researchers to examine how too much or too little self-efficacy might impact tutors' growth. The same might be done by examining tutors' writing over the course of a semester when they are receiving explicit instruction with writing and tutoring self-efficacy in tutor education programs. Researchers could collect similar writing assignments or genres from the beginning and end of the semester to see whether they have improved.

Additionally, we suggest studies that monitor tutors' self-efficacy in both tutoring and writing over time. Such studies might use and adapt the TWAWSES to better fit their local context, then administer it at the beginning of the semester, offer explicit instruction on tutor education throughout the semester/year, and then administer the survey at the end of a semester/year. This would allow for an understanding of how tutoring and writing self-efficacies change over time. An additional layer of inquiry to this work might be to conduct intervention studies where tutors explicitly work on a particular tutoring or writing task and see how this impacts their self-efficacy with this task over time. This intervention study may be especially suited to help WCAs understand the areas in which tutors need more self-efficacy with a particular task, or when they've become too comfortable and need to learn more about that task.

Besides monitoring self-efficacy and utilizing different methodologies, we suggest looking at identity and contextual factors that may shape self-efficacy. These factors include but are not limited to gender, mental health, personality, cultural background, and socio-economic background. All of these factors can shape the self-efficacy tutors have, and, while we briefly mention them in the introduction and discussion as having this potential to shape self-efficacy, they were not a focus of this study. Follow-up work that examines these factors in relation to self-efficacy could give deeper insights into how and why tutoring and writing self-efficacy manifest in specific ways.

Lastly, self-efficacy also has the ability to impact tutors' long-term development through helping them engage in learning transfer. A specific study may examine the impact of self-efficacy as a framework for tutor education over a tutor's entire career. We believe that by doing so, we will see even more evidence (see Kail et al.'s Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project) that writing centers have long-term impacts on not only writers, but tutors as well.

NOTES

1 (back to text) We would like to note that numerous factors may impact one's self-efficacy, which can present difficulties in working on self-efficacy. Factors such as gender, age, body presentation, culture, and/or mental health may affect one's self-efficacy. Our suggestion here is not meant to trivialize how difficult this process may be for some, but rather that developing self-efficacy overtime is a worthwhile process that is different for each individual tutor.

Works Cited

Baird, Neil, and Bradley Dilger. "How Students Perceive Transitions: Dispositions and Transfer in Internships." College Composition and Communication, vol. 68, no. 4, 2017, pp. 684-712.

Bandura, Albert. "Guide for Constructing Self-Efficacy Scales." Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. Edited by M. Frank Pajares & Tim Urdan, vol. 5, Information Age Publishing, 2006, pp. 307-37.

Bartlet, Margaret. "Am I a Good Tutor?" The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 19, no. 6, 1995, p. 8.

Bleakney, Julia. "Ongoing Writing Tutor Education: Models and Practices." Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Bleakney.html.

Bromley, Pam, et al. "Transfer and Dispositions in Writing Centers: A Cross-Institutional Mixed-Methods Study. Across the Disciplines: A Journal of Language, Learning, and Academic Writing, vol. 13, no. 1, 2016.

Buck, Elisabeth H. "From CRLA to For-Credit Course: The New Director's Guide to Assessing Tutor Education," Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Buck.html.

Cozart, Stacey M., et al.. "Negotiating Multiple Identities in Second- or Foreign-Language Writing in Higher Education." Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer, edited by Chris M. Anson and Jessie L. Moore, The WAC Clearinghouse, 2017, pp. 299-330.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Jennifer Wells. "Beyond Knowledge and Skills: Writing Transfer and the Role of Student Dispositions." Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, https://compositionforum.com/issue/26/beyond-knowledge-skills.php, Accessed 17 Aug. 2018.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Roger Powell. "States, Traits, and Dispositions: The Impact of Emotion on Writing Development and Writing Transfer Across College Courses and Beyond." Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016.

Ekholm, Eric, et al. "The Relation of College Student Self-efficacy Toward Writing and Writing Self-regulation Aptitude: Writing Feedback Perceptions as a Mediating Variable," Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 20, no. 2, 2015, pp. 197-207.

Hawkins, R. Evon. "'From Interest and Expertise': Improving Student Writers' Working Authorial Identities." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 32, no. 6, 2008, pp. 1-5.

Johnson, Karen G., and Ted Roggenbuck, editors. How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection. 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/JohnsonRoggenbuck.html.

Kail, Harvey, et al. The Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project, 2015, https://writing.wisc.edu/pwtarp/, Accessed 18 Aug. 2018.

Lape, Noreen. "Training Tutors In Emotional Intelligence: Toward a Pedagogy of Empathy." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 33, no. 2, 2008, pp. 1-6.

Lawson, Daniel. "Metaphors and Ambivalence: Affective Dimensions in Writing Center Studies." The Writing Lab Newsletter vol. 40, no. 3-4, 2015, pp. 20-27.

Mackiewicz, Jo, and Isabelle Thompson. Talk about Writing: The Tutoring Strategies of Experienced Writing Center Tutors. Routledge, 2015.

Nowacek, Rebecca S., and Bradley Hughes. "Threshold Concepts in the Writing Center: Scaffolding the Development of Tutor Expertise." Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State UP, 2015, pp. 171-85.

Pajares, M. Frank. "Self-efficacy Beliefs, Motivation, and Achievement in Writing: A Review of the Literature." Reading & Writing Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 2, 2003, pp. 139-58.

Pajares, M. Frank, and Margaret Johnson. "Confidence and Competence in Writing: The Role of Self-efficacy, Outcome Expectancy and Apprehension." Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 28, no. 3, 1994, pp. 313-31.

Pigliacelli, Mary. "Practitioner Action Research on Writing Center Tutor Education: Critical Discourse Analysis of Reflections on Video-recorded Sessions," Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Pigliacelli.html.

Pittock, Sarah and Erica Cirillo-McCarthy. "Let's Meet in the Lounge: Toward a Cohesive Tutoring Pedagogy in a Writing and Speaking Center," Johnson and Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Pittock&Cirillo-McCarthy.html.

Powell, Roger, and Kelsey Hixson-Bowles. "Too Confident or Not Confident Enough?: Designing Tutor Professional Development with Tutors' Writing and Tutoring Self-Efficacies." Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, forthcoming.

Schmidt, Katherine M., and Joel E. Alexander. "The Empirical Development of an Instrument to Measure Writerly Self-Efficacy in Writing Centers." The Journal of Writing Assessment, vol. 5, no. 1, 2012, http://www.journalofwritingassessment.org/article.php?article=62, Accessed 18 Aug. 2018.

Smagorinsky, Peter. "The Method Section as Conceptual Epicenter in Constructing Social Science Research Reports." Written Communication, vol. 25, no. 3, 2008, pp. 389-411.

Wardle, Elizabeth, and Nicolette Mercer Clement. "Double Binds and Consequential Transitions: Considering Matters of Identity During Moments of Rhetorical Challenge." Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer, edited by Chris M. Anson and Jessie L. Moore, The WAC Clearinghouse, 2017, pp. 161-80.

White, Shaun T. A Case Study of Perceived Self-Efficacy in Writing Center Peer Tutor Training. Thesis, Boise State University, 2014.

Williams, James D., and Seiji Takaku. "Help Seeking, Self-Efficacy, and Writing Performance among College Students." Journal of Writing Research, vol. 3, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1-18.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We'd especially like to thank our teacher and mentor Dr. Dana Driscoll for inspiring this project and offering guidance throughout its life. Additionally, we thank Jessica Reyes, Dr. Justin Nicholes, Dr. Tony Schiera, Shannon Paisley Josephine Israelsen, and two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading, useful feedback, and guidance throughout the publication process.

BIO

Kelsey Hixson-Bowles is the Coordinator of the Writing Center and Writing Fellows Program at Utah Valley University. She studies writing center/writing fellows praxis, dispositions, learning transfer, and intersections between social justice and writing studies. She is currently completing her doctorate at Indiana University of Pennsylvania and serves as the Graduate Co-Editor of The Peer Review.

Roger Powell is an assistant professor of English and writing coordinator for the Center for Academic Excellence at Buena Vista University. His research explores composition pedagogy and theory, writing centers, responding to student writing, dispositions, and learning transfer.