Jared Featherstone

James Madison University

Rudy Barrett

James Madison University

Maya Chandler

University College London

Students enter the James Madison University Writing Center and sit around a long conference table. As they wait for their tutor education class to begin, they are scrolling and texting on their smartphones, checking over assignments on their laptops, drinking coffee, and chatting about the weekend. The typical classroom scene changes abruptly when the professor takes a seat and picks up a set of Tibetan Tingsha bells. The students quickly put phones in backpacks, close laptops, sit up straight, and close their eyes. The chime rings and the activity dissolves into silence, leaving the students completely still for a few minutes. When the chime rings again, class begins.

|

| Figure 1. Photo of James Madison University students meditating during their tutor education course. February 7, 2018. Source: Sarah Featherstone Photography. |

After a decade in writing centers and two decades in meditation practices, I began to see connections between the seemingly disparate practices of tutoring and meditation. Given my own positive experiences and the abundance of empirical research on mindfulness meditation, I thought that the tutors and, indirectly, the clients of our writing center, could benefit greatly from this practice. The most logical place to integrate mindfulness practice was tutor education.

For the past four years, mindfulness meditation has been a regular part of the semester-long, 3-credit course, Tutoring Writing, which all prospective tutors must take before applying for a position. This chapter will give an overview of mindfulness and its connections to learning, explain my rationale and the ways in which our center has integrated mindfulness into tutor education, analyze my IRB-approved qualitative data and practice narratives, offer materials for others to use, and give suggestions for directors planning to integrate mindfulness into tutor education.

Definitions and Context for the Intervention

For those who are unfamiliar with the term, mindfulness is the ability to be sharply aware of experiences as they occur in real time. When people are mindful, they maintain awareness of immediate, real-time experience as opposed to being carried away by fantasies, mental projections, judgments, or memories. For example, people showering mindfully would be aware of the feeling of the hot water on the skin, the scent of the soap, and the sound of the water hitting the tile. They might even notice themselves having thoughts about a particular event coming up that day. People showering unmindfully would be lost in thought, completely unaware of the immediate physical experience of showering and also unaware that they are lost in thought.

In the writing center, a mindful tutor would notice when planning, fantasies, and commentary are compromising their attention and use an attentional anchor, such as the sensation of their feet touching the floor or the movement of their breath, to stay present and focused on the client's words. When self-doubt arises, the mindful tutor acknowledges and accepts this mental pattern but does not let it interfere with the process of helping the client with a writing assignment. With this reduction of mental noise and ability to self-regulate attention, a tutor can remain focused on the collaboratively established goals of the writing center session.

Mindfulness meditation, differentiated from the broader term mindfulness, is a particular method of training the mind to be more present and aware. In mindfulness meditation, practitioners take time out from daily tasks to pay attention to their own breathing, bodily sensations, and ambient sounds. When practitioners realize that the mind has wandered away from these immediate sensory anchors, they choose to refocus on those anchors. Practicing these skills in silent, sitting meditation has been linked to increased mindfulness in daily life (Salmon et al. 154). Research suggests that this practice changes neural pathways and increases grey matter in the brain (Hφlzel et al. 6-10). When writing tutors practice mindfulness meditation regularly, they are developing both metacognitive awareness and the ability to self-regulate, which, I will argue, can be applied in a tutoring context.

|

| Figure 2. Photo of resin Thai Buddha statue taken in Harrisonburg, VA. March 4, 2018. Source: Sarah Featherstone Photography. |

The modern, ubiquitous practice of mindfulness meditation is directly rooted in the 2500-year-old teachings of the Buddha (Kabat-Zinn, "Some Reflections..." 289). Importantly, these teachings are also clear that no particular belief system, dogma, rituals, or cultural practices are necessary to receive the benefit of these practices. In many ways, the teachings were secular from the beginning. However, as Buddhism spread throughout Asia, it fused with folk religions and spiritual systems already in place (Eckel). Consistent with those original teachings is that the practice of mindfulness, by undoing harmful habits of mind and fostering self-compassion, is a reliable way to reduce suffering. The modern applications of this practice, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction, have removed any cultural remnants and de-emphasized spiritual implications to approach this practice strictly in terms of mental and physical wellbeing (Salmon et al. 135-39).

Given the trajectory of mindfulness meditation from the ancient teachings of the Buddha to its current ubiquity in psychology, health, and popular media, teaching meditation to tutors might not sound as strange as it would have in the early days of writing centers. Jon Kabat-Zinn's founding of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in 1979 was a pivotal moment for the application of mindfulness outside of traditional Buddhism (Salmon et al. 132-33). The development of the regimented Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) course enabled decades of replicable, empirical research on the benefits of this practice. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction offers reliable, evidence-based techniques for practicing and teaching mindfulness meditation to inexperienced participants.

Data supporting the benefits of mindfulness practice is not hard to find. An overview of empirically-supported benefits shows that the practice results in improved emotional regulation, response flexibility, information processing speed, empathy, and compassion (Davis and Hayes 198). With writers arriving with diverse cultural backgrounds, learning needs, and ability levels, tutors must be able to quickly assess the learner and the writing situation in order to be effective in a session. For centers that strive for inclusivity and work to establish themselves as a safe space in the institution, contemplative practices that build compassion and empathy among tutors would be worth incorporating. In looking specifically at studies on college populations, Bamber and Schneider concluded that the practice reduces stress and increases mindfulness (1). Tutors experience cyclical fluctuations in their stress levels similar to the writers they see in the writing center. To avoid allowing their own stress to reduce their tutoring effectiveness, the stress management applications and real-time awareness developed in mindfulness practice can be useful. Importantly, emerging research more specifically connecting mindfulness to teaching and learning reveals the effectiveness of mindfulness practices. Amishi Jha demonstrated that mindfulness practice increases working memory and attention (Improving Attention). Reading papers with multiple problems in oft-busy writing centers, within the context of their own loaded schedules, tutors could greatly benefit from the ability to regulate their attention.

The integration of meditation into university courses and programming is also not new. For example, the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society has been working to integrate contemplative practices like meditation into the academy since the 1990s and began focusing on higher education with the 2010 formation of the Association for Contemplative Mind in Higher Education, supporting contemplative fellowships in universities across the country, annual conferences, summer institutes in contemplative pedagogy, and a scholarly journal ("Our History"). In order to help more faculty and administrators teach mindfulness effectively, two Duke University psychiatrists, Holly Rodgers, MD., and Margaret Maytan, MD., founded the Center for Koru Mindfulness in 2013, after a decade of developing an evidence-based approach to teaching mindfulness to emerging adults ("About Koru"). The Koru Mindfulness Curriculum is being taught at more than 60 universities, including Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Johns Hopkins, and MIT ("Where Is Koru").

Mindfulness in Writing Center Work

The potential value of integrating mindfulness can be seen in the work of scholars attempting to identify the most fundamental traits or skills that enable significant change within a learner. In Carol Dweck's popular work on mindset, she identifies two general ways to understand one's abilities: a fixed mindset or a growth mindset (6). She asserts that having a growth mindset has significant benefits for learning and performance (Dweck 57-70). Importantly, the initiation of this fundamental, inner change from a fixed mindset to a growth mindset hinges on a person's awareness of fixed-mindset thoughts. A defining feature and result of mindfulness meditation is increased metacognition. With this increased awareness of thinking, students can see, perhaps for the first time, their fixed mindset in action. Mindful tutors could notice when a fixed mindset, their own or the client's, is affecting a tutoring session. Unmindful tutors, however, could inadvertently reinforce a client's fixed mindset if they are unaware of these patterns. As most writing center tutors know, writers often arrive with a fixed mindset about their writing ability, as evidenced by their immediate declaration of I'm a bad writer, or writing is not my thing, as if those were permanent, unalterable facts. Although Dweck does not name mindfulness meditation as a way to train awareness, other research has proven it to be a reliable means of increasing awareness of mental activity (Salmon et al. 154).

Similarly, Lavelle and Zuercher identify ways in which mental habits and patterns, specifically students' perceptions about writing and about themselves as writers, influence the ways students approach writing tasks (376-78). Among the recommended ways of moving students from surface approaches to composition, such as "spontaneous-impulsive" and "procedural," to deep writing approaches, such as "reflective revision" and "elaborative," is to "provide meaningful feedback" (376-78). In order to provide this feedback, tutors need to have awareness of their own writing approaches (most students have different approaches for different types of writing tasks) and enough empathy to understand the roots of a student's approach, avoid judging that student, and respond in an encouraging way. As transdisciplinary writing consultants, tutors who have had mindfulness training, which builds both awareness and empathy, would be well-positioned to influence a student's writing approach. The sharp, real-time awareness they are building with mindfulness practice, combined with the intellectual understanding of the common writing approaches of student writers, enables tutors to identify ineffective approaches and collaboratively help students move beyond their habitual approaches.

Barry Zimmerman's scholarship on self-regulated learning also points directly to the important inner work of learning (69), though there is no specific mention of mindfulness as a means. In order for a student to learn effectively and deeply, going beyond regurgitation or surface performance, they need to develop the metacognitive skills that characterize self-regulated learners: self-monitoring, setting appropriate goals, and developing effective strategies (69). Building both concentration and metacognitive awareness, mindfulness could be an effective means of increasing a learner's ability to self-regulate. Several studies have shown that tutoring correlates with increases in self-regulated learning (van den Boom et al. 544-45; Gynnild et al. 154; Beaumont et al. 346-47).

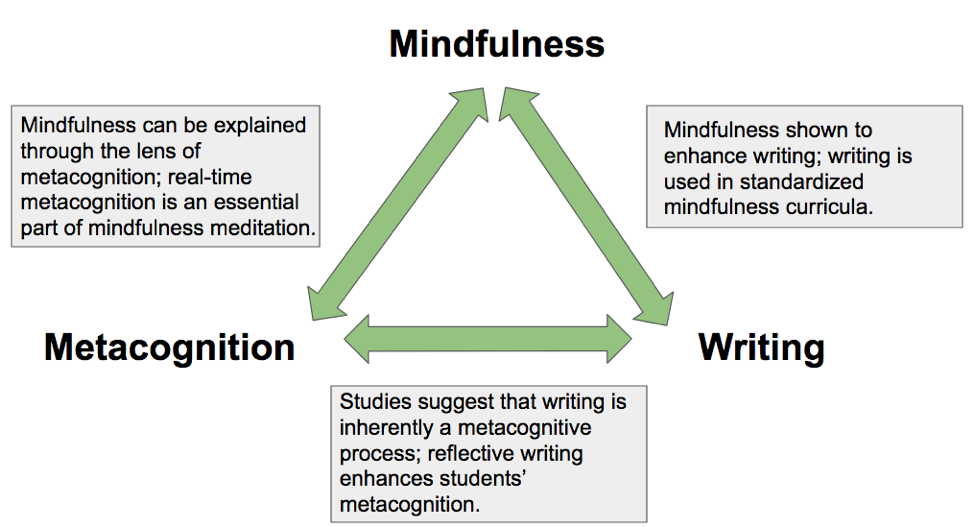

The connections among mindfulness, writing, and metacognition are useful to consider in understanding the relevance of mindfulness to the education of writing tutors. In a variety of studies, mindfulness has been investigated as a means to enhance the writing of university students (Jones 52-55; Poon and Danoff-Burg 888-91; Wald et al. 526-27). Not only has mindfulness been used to enhance writing, but writing has been used to enhance mindfulness. Both the standard Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and the Koru Mindfulness Curriculum contain a reflective writing component ("Home Practice Materials"; Rogers and Maytan 3-14). After studying student writers with eye-tracking technology and considering relevant theory, Douglas Hacker et al. characterized writing as "applied metacognition" (169-70). In their pilot study, the researchers used an eye-tracking technology to monitor a student's focus during writing and revision. Because pupil dilation correlates with an increase in cognitive processing, they were able to begin to analyze and track the amount of cognitive work involved in the writing process. They concluded that "writing requires both thinking and thinking about that thinking, and the best way to derive a better understanding of the complexities of writing is by getting as proximal to thinking as possible" (170). Lastly, using both empirical and theoretical support, Jankowski and Holas define mindfulness through a metacognitive framework (76-77). The following figure gives a visual sense of these connections.

|

Figure 3. A visual representation illustrating the interconnectedness between mindfulness, metacognition, and writing. See Jones(52-55), Poon and Danoff-Burg (888-91), and Wald et al.( 526-27) for research on how mindfulness enhances university students' writing. For research on how writing enhances mindfulness, see Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, Koru Mindfulness Curriculum, "Home Practice Materials," and Rogers and Maytan (3-14). To access research on writing characterized as applied cognition, refer to Douglas Hacker et al. (169-70). For more information on understanding mindfulness through a metacognitive framework, see Jankowski and Holas. Graphic created by Jared Featherstone. |

A move toward studying the internal traits or characteristics, such as metacognition, that enable effective writing is also evident within the field of writing studies and composition. As Cahill et al. note in their chapter of this digital edited collection, the 2011 CWPA/NCTW/NWP Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing puts an emphasis on important "habits of mind" for college students to attain. Though Cahill et al. emphasize other habits, the habit that is of central concern to this chapter, in integrating mindfulness practices into tutor education, is metacognition. In the discipline of writing center work, scholars have identified some of the potential ways in which tutoring might be informed by meditation or the philosophy related to meditation traditions. The following scholars refer specifically to the Zen tradition, which uses practices nearly identical to secular mindfulness meditation, though they are situated in the context of Buddhist ritual and teaching. Deborah Murray identifies aspects of Zen practice and tradition beneficial to writing tutors, such as "active presence," the ability to remain calm in stressful situations, and maintaining focus during routine tasks (12). Although some of the connections she makes align with our efforts to integrate mindfulness into tutor education, Murray does not go as far as to suggest meditation for tutor education or offer a method for doing so. Ericka Spohrer identifies Zen meditation as a potential way for tutors to remain flexible and not become hindered by a rigid anchoring to writing center theory in tutoring sessions (11-12). She cautions against becoming too goal-oriented in tutoring practice and sees the open-ended approach taken in Zen meditation, in which the practitioner lets go of expectations and control in practice, as potentially beneficial to tutors (12-13). Again, she stops short of suggesting integration into tutor education or how this understanding might be imparted to tutors.

Although writing center scholars like Murray and Spohrer indicate the possible benefits of writing tutors practicing meditation, writing centers are a long way from realizing the full potential of systematic integration of mindfulness into tutor education. There are empirically-demonstrated results of mindfulness training on the stress management and learning of college students. There is support for this cognitive work from within the overlapping discipline of writing studies. The qualities of mind established in mindfulness practice and those desired for writing tutors align with each other. If writing centers are committed to the ongoing development of their practices, they should follow the lead of disciplines and institutions who have made mindfulness a part of their pedagogy and research.

Although writing center scholars like Murray and Spohrer indicate the possible benefits of writing tutors practicing meditation, writing centers are a long way from realizing the full potential of systematic integration of mindfulness into tutor education. There are empirically-demonstrated results of mindfulness training on the stress management and learning of college students. There is support for this cognitive work from within the overlapping discipline of writing studies. The qualities of mind established in mindfulness practice and those desired for writing tutors align with each other. If writing centers are committed to the ongoing development of their practices, they should follow the lead of disciplines and institutions who have made mindfulness a part of their pedagogy and research.

A Course Ripe for Integration

At our writing center, all students intending to apply for a peer tutor position must take the 3-credit, 300-level course, Tutoring Writing, a course detailed in a 2010 WLN article (Schick et al. 2-3). This rigorous class has always included an overview of foundational writing center theory, a 16-hour apprenticeship in the writing center, an exploration of best practices, input from guest speakers, and development of genre and grammar knowledge. In the fall of 2012, after attending the weeklong summer institute of the Association for Contemplative Mind in Higher Education that included a workshop in contemplative assignment design, I decided to integrate mindfulness training into the Tutoring Writing course. The course syllabus includes a rationale for the inclusion of mindfulness meditation.

The seeds of contemplative pedagogy were already present in the course in at least two ways. The first seed is the fruitful "How I Write" assignment, a fixture of the course that comes directly from the Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors (Ryan and Zimmerelli 49-50.). Having students detail and reflect upon their writing habits and processes helps them become aware of their habits of mind. They examine, perhaps for the first time, their assumptions, attitudes, and cherished notions about writing. This assignment is a step in the direction of mindfulness of thought, one of the four classical foundations of mindfulness taught by the Buddha (Rinpoche). The second seed of contemplative pedagogy in the course is the reflection papers students are required to write after each phase of the 16-hour apprenticeship. Of particular relevance are the third and fourth reflection papers because the sessions described involve co-tutoring, tutoring under observation, and tutoring alone. Ideally, reflecting on those sessions involves an examination of one's thinking, assumptions, choices, and judgements.

When planning to incorporate a meditation component, I anticipated tutor confusion about why students were meditating in a tutor education course, resistance to an approach so radically different from a typical college course, and discomfort with the idea of sitting still with very little stimulation. After the first or second class meeting, I decided to assign a few readings, such as "A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy Mind," and videos like "The Scientific Power of Meditation" that explain the empirically-studied benefits of mindfulness practice for health, learning, and general wellbeing. I also sought to point out the work of the Association for Contemplative Mind in Higher Education, the UMASS Stress Center for Mindfulness and the Koru Mindfulness Center to let students know that this integration is happening at reputable institutions across the country.

In addition to considering potential student resistance and confusion, I also needed to face the practical matter of how much meditation was necessary to bring about the desired benefits, and whether that amount of meditation was feasible given the other important content necessary for our 3-credit tutor education course. At the time that this classroom mindfulness intervention began, the only available, reliable data indicating measurable benefits of mindfulness meditation came from the standardized, 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction course, which includes over 42 hours of meditation ("Home Practice Materials"). Under that standard, my students would have had to complete approximately three hours of meditation per week in a 15-week course. For brand new meditators, that can be an intimidating and difficult amount of time to spend in meditation.

Fortunately, during the same academic year that I introduced mindfulness into tutor education, Jeffrey Greeson, et al. conducted a randomized, controlled trial that examined the effects of a smaller dose of meditation, using a structured 4-week program called Koru, on college students. The 4-week Koru Mindfulness course, which focuses on emerging adults, includes a total of 4.5 hours of formal meditation practice (Rogers and Maytan 3-14). The researchers found the largest effect size in the measure of the subjects' mindfulness ability (Greeson et al.), demonstrating a strong correlation between low doses of mindfulness practice and measurable increases in student mindfulness, prompting me to focus on the yet unexamined combination of mindfulness and tutor education.

These developments in the field gave me some confidence that a relatively small dose of meditation could have a noticeable effect on college students. The tutor education course at JMU initially included only three hours of meditation, but, as I developed the intervention over time, I steadily increased the amount of practice, eventually matching the 4.5 hours of the evidence-based Koru training. What follows is an explanation of the details of this integration, so that other writing center directors can follow a similar course.

Mindfulness Meditation Training Logistics

My goal for the mindfulness integration was to sharpen the students' metacognitive awareness, along with the benefits of enhanced concentration and reduced stress. Initially, mindfulness training was integrated in two ways. At the start of every class meeting, students were given instructions in mindfulness meditation before practicing meditation together. During the first few weeks of the semester, in-class meditations were guided by the instructor. Depending on the length of class meetings and whether out-of-class meditation was assigned, in-class meditations were 2-5 minutes long. After that period, the familiar meditation techniques were practiced in silence. The basic guidelines for practice were as follows:

- Find a posture that enables you to be both relaxed and alert.

- Choose an anchor for your attention, a place to focus your awareness. Traditional anchors are breath, bodily sensations, or sounds.

- For the duration of the meditation session, let the anchor be the focus of your attention and the place to return your attention when you notice that your mind has wandered.

- Whenever you notice that your mind has wandered away from the anchor, bring your attention back to the anchor without any need to judge or evaluate this experience.

|

| Figure 4. A tutor education course meditates at the start of class in the University Writing Center at James Madison University. February 7, 2018. Source: Sarah Featherstone Photography. |

As you can see, the instructions are simple. However, if you have tried this, you are aware that simple does not mean easy. Students will find that their attention wanders frequently and that they judge themselves and the practice harshly. Despite this, I offer the first meditation session on the first day of class with very little context or rationale. I do this because I want their raw reactions to the practice. I do not want them to go through the motions and give me the response they think I want to hear. Immediately following what is likely the first meditation experience ever for most of the students, I invite them to share. I simply ask them to tell me about their experience during those 1-2 minutes of meditation. This reflection time is important because they soon see that everyone is experiencing similar difficulties. This also gives an excellent opportunity for the instructor to clear up the misconceptions that are likely to be voiced. Here are a few common problems expressed by students.

I can't seem to stop my thoughts. The instructions did not say to forcefully stop your thoughts, but students have this popular notion about meditation. My response is that they do not have to force their minds to stop thinking. Instead, the intention is to remain aware of our experience as it happens. When one becomes aware that one is lost in thought, those thoughts naturally quiet down or dissolve. In that moment, you can then return your focus to the attentional anchors. There is no need to struggle.

I don't know if I'm doing it right. A fitting response from students often raised in the culture of grades and scores. I explain that they might see if it is possible to set that evaluative framework aside and practice with the idea of carrying out an intention (to be aware of what's happening as it is happening) rather than keeping score.

My mind wandered so many times. I don't think this is for me. This might remind you of the proclamation often made by writing center clients: I'm just bad at writing. One response is to point out that they are looking at the glass as half-empty. In order to know that the mind wandered multiple times, that student had to be aware. The half-full way to look at that experience is that the student became aware of mental activity so many times. It is this coming to awareness and refocusing the attention that retrains the brain. Another response is to note that empirical research suggests that the brain's structure and neural pathways can change as a result of mindfulness practice.

Although these common meditation problems were expressed, I knew that they were necessary difficulties and misunderstandings to move beyond. These were opportunities for learning. These were the same issues reported to me by adults in meditation classes I had taught at yoga studios. Importantly, students were also telling me that they felt different after meditating in class. They felt more focused and calm. From my vantage point in the front of the classroom, I could sense a tangibly less scattered and tense room. I was fascinated that the atmosphere of my classroom had changed after just a few minutes of silent meditation. These changes were apparently noticeable to outsiders as well. I brought one of these groups of students to see a presentation from a librarian. Before she arrived in the library classroom, we practiced our class meditation as usual. The librarian had no idea we had practiced meditation in the class, but, after the presentation, she asked what I was doing with these students. When I asked for clarification, she said that she had never seen such a focused, calm, and attentive group.

This informal, anecdotal, positive feedback made me want to understand the effects of the mindfulness intervention in more depth. I wanted to know exactly how mindfulness training might affect the way tutors think, the way they respond to clients, and the way they embody the best practices of our discipline. With IRB approval, I conducted a qualitative analysis of the survey responses of 42 prospective tutors from several sections of the tutor education course. As a complement to the survey, I asked an undergraduate peer tutor and a graduate assistant to contribute to this chapter by reflecting on their experiences as mindful tutors.

A Method to the Mindfulness

To determine the effectiveness of meditation in a tutor education course, I decided to follow Weimer's, approach of documenting "personal accounts of change" (56). This approach often involves an instructor introducing a change that attempts to more effectively meet the course goals and student learning needs (57). In this case, I obtained the accounts of tutors, both learners in the tutor education course and hired tutors, who experienced change related to the mindfulness intervention.

I surveyed four sections of the 300-level tutoring course that all our prospective tutors must take before applying for jobs in our center. To get a basic sense of their perception of the intervention, I asked the following closed-ended question.

"Has the mindfulness training and practice done as part of the WRTC 336 class influenced the way you tutor?"

I then asked open-ended questions to help understand why the mindfulness practice affected their tutoring or why it did not. Approximately 60 subjects from tutor education courses between 2012 and 2017 were surveyed, and I received responses from 42 tutors. I conducted conventional qualitative content analysis of their responses using NVivo data analysis software. The analysis included word frequency queries to determine the words that appeared most often in the open-ended responses. The software was also used to code the data according to emergent themes and to assist in the analysis of those themes.

To drill down into the experience of these tutors more deeply, I collected the reflections of two tutors, both of whom were participants in the survey, had multiple semesters of experience following their tutor education course, and were particularly interested in exploring this topic through scholarship. These reflections were recorded in video form and are embedded later in this chapter. With a breadth of tutoring experience, the graduate assistant and undergraduate peer tutor featured in the videos are able to offer more detailed, first-hand accounts of the experience of mindfulness meditation in the tutor education course and its influence on their tutoring practice.

Fruits of the Practice

The responses to our closed question about the influence of meditation training on tutoring showed that 31 of the 42 tutors (74%) who participated in the study felt that the meditation training influenced their tutoring as opposed to 11 (26%) who did not report an influence. Although many of the students who did not report an influence declined to comment on the reasons, the available responses suggest two potential issues. The first issue is a basic rejection of the practice, seemingly due to discomfort or personality. In the same way that faculty themselves or other course content might appeal to some members of a class but not all, the comments in the follow-up question indicate that some students simply didn't like practicing meditation.

The second issue is a disconnect between the practice of meditation and the practice of tutoring. Whereas most students were able to apply the skills of meditation to tutoring with little or no prompting, some students seemed to need more help drawing connections, as seen in the following comments.

"I don't think about it unless I'm being asked to meditate in class."

"I don't think about mindfulness on a regular basis while tutoring. For the most part, I don't give it any thought during a session."

At least part of the issue here was an effort on the part of the instructor to avoid pushing the students to make or at least purport to make inauthentic connections between mindfulness and tutoring. Because I was collecting data and attempting to understand these potential connections, I deliberately held back on making very explicit connections to tutoring until late in the semester. The survey comments indicate that, for some students, this caused confusion or annoyance. The explicit connections between mindfulness meditation and tutoring practice should be made early on in the semester to help motivate them to integrate the practice into their tutoring approach.

Although an external measure would be more reliable, I can say that, from the viewpoint of 74% of the tutors themselves, mindfulness meditation influenced the way they tutor. The query results and themes that emerged from the text fields of the open-ended question give a sense of exactly how the meditation training influenced the subjects' tutoring. When I queried the data to find the top seven words or, more accurately, word forms, appearing in the tutors' text responses, the following terms emerged: mindfulness, focus, aware, feel, client, able, and attentive.

Because the word "mindfulness" was in the question and the fact that, as a concept, it encompasses most of the other words in the list, I did not find it worth probing. The word frequency query was helpful in that it immediately established some potential themes to mine for in the closer content analysis. After re-reading the entries, considering the context of the students' words, and then coding the data from the 42 completed surveys, the following themes emerged: mental focus (17), stress reduction (11), metacognition (10), self-regulation (9), listening skills (9), and empathy (6). A closer look at each of the emergent themes gives a better sense of the impact tutors felt that meditation had on their tutoring. For each of the excerpts from the qualitative data, our two experienced tutors, Rodolfo and Maya, elaborate on their subjective experience of that theme, through our embedded videos.

Mental focus. The subject responses that fit the "mental focus" theme revealed at least two types of focus: those related to themselves and those relating to the work of tutoring. Both of these aspects of focus align with the empirical findings of Jha, a neuroscientist who uses brain scans to provide empirical evidence for the positive effect of meditation on working memory and attention (Improving Attention). When referring to the first type of focus, the tutors indicated that the mindfulness practice was a tool for them to notice when they lost focus on the session, due to internal noise or external distraction, and to return their attention to the session.

"Ever since I started mindfulness practice, I am more aware of when I do lose focus, and am able to shift my focus back to what I need to concentrate on."

"... it has helped me be attentive to the tutee and to avoid distractions."

Our over-committed, plugged-in students often struggle to maintain focus on a single task of any kind. They have multiple obligations competing for their time. They have multiple devices, apps, and tabs open at any given time. Though the ability to focus is essential in both academic and professional contexts, students are rarely taught any skills to effectively manage attention. In their chapter of this collection, Thomas Earles and Leigh Ryan explain their process of instilling professionalism among tutors, identifying "appropriate use of technology" and "being focused and attentive" as necessary components. Given their findings and the frequency of this theme in our qualitative data set, the potential of mindfulness to help tutors self-regulate attention and technology habits suggests the applications to tutoring.

The first aspect of focus, the management of internal and external distractions, is the application of skills trained explicitly in mindfulness meditation. In meditation, one is frequently redirecting attention back to present moment anchors, such as physical sensations or breathing. In the survey responses, I see this same noticing and redirecting at play. Once a tutor is able to manage this level of internal distraction, they can then apply focusing skills to particular issues present in the client's writing. For example, a tutor might have an exam directly after their shift or a deeply personal connection to the paper's subject matter. The focus trained in mindfulness practice can help a tutor navigate this interference.

The second type of focus within this emergent theme seems to refer to competing aspects of the client's paper or behavior. For example, a client might be rapidly switching between complaining about the professor and giving important details about the assignment's requirements. Within the paper itself, the tutor might find a variety of both higher order and later order concerns, far more than they could cover in a single session. A tutor without a means to steady the mind and focus on a particular chosen object of attention might be lost in such a session. The type of in-session focus is alluded to in both the upcoming embedded video of interviews with experienced mindful tutors (See Figure 5) and in the mental focus theme from the qualitative data, as in the following excerpt.

"My working memory feels more attune[d] with what's going on during the consultation. As a result, I'm able to focus on relevant issues and identify the writer's needs."

Stress reduction. The 2017 American College Health Assessment data shows that a quarter of college students surveyed reported having substantial anxiety within the last two weeks (32) and also reported that anxiety affected their academic performance (47). With anxiety and other stressors rampant on college campuses, it makes sense to equip our tutoring staff with stress management skills. In alignment with the findings of numerous empirical studies, our qualitative data set includes multiple references to the ability to remain calm or to become calm in the face of stress, during tutoring sessions. In this example, I see evidence of a tutor applying the breath focus and systematic body relaxation from the mindfulness meditation practice in a tutoring session, in an effort to manage stress.

"When I feel very overwhelmed with the session I take a couple of seconds to breathe and relax my posture like the beginning of meditation sessions."

This ability is important because instead of experiencing mounting stress, the tutor has a reliable means to respond to perceived stress as it happens. Without this skill set, a tutor's effectiveness in this situation is likely to be compromised by stress.

Metacognition. As for the metacognition theme, I see that tutors report being aware of thoughts, feelings, and processes they experience. Without this awareness, tutors cannot look critically at their tutoring practice and habits of mind.

"...more aware of...my thoughts and actions."

"I try to be very aware, as I'm tutoring, of the way I'm acting and reacting to the client. Having an awareness of my own feelings and reactions."

The second excerpt gets directly to the important distinction between the past-tense metacognitive awareness characteristic of reflective writing assignments and the real-time metacognition developed in mindfulness meditation. The reflection done by a tutor in a session report, for instance, looks back on the experience, including the choices made and mental processes engaged. In the best case, this reflection is accurate and useful in helping tutors make changes to their practice that will be implemented in future sessions. However, the tutor above was, "aware, as I'm tutoring," which enables that tutor to make immediate changes that impact a session.

Self-regulation. The meditation community often points out the difference between reacting and responding. The former is often automatic, unexamined, and in accordance with existing mental habits. However, the latter offers the possibility of interrupting automatic responses or habits and responding more strategically. Self-regulation, then, is the next level beyond metacognition. If one develops the metacognitive awareness to see one's habits of mind, one needs self-regulation to act effectively based on that awareness. The following excerpts show how this theme evokes the ability to make appropriate adjustments that might enhance performance.

"...helps me understand the dynamic I'm building with the client and be able to modify my tactics if I feel it isn't going as well as it should be."

"I think the biggest benefit is for the first time I fully REALIZE that my mind is wandering, so I can make the necessary adjustments."

Again, I can see the overlap in themes, how the ability to focus and sharpen metacognitive awareness would enable the tutor to self-regulate. Given the influence self-regulation has on performance (Nilson 1-14), the possibility of instilling these skills through mindfulness training is promising as it encourages real changes in thought processes.

Listening skills. Another reported result of mindfulness training for tutors is enhanced listening skills. The ability to respond effectively to clients hinges on listening, and some subjects in the study referred directly to this perceived change. Quite often, after some weeks of mindfulness practice, students report that they now notice how often their mind is wandering when in conversation with another person. While attempting to listen, they are also planning, thinking of what they will say next, forming judgements, and daydreaming. With mindfulness practice, tutors are given a sharpened awareness of and the means to manage their attention. Those skills allow tutors to devote more effort to listening, which can enable them to notice what is said, what is not said, the tone of speaking, and body language.

Another issue related to listening is the ability to tolerate silence. After the first few meditation sessions in the tutor education course, some students typically report a feeling of discomfort that comes with silence and inactivity. Over time, mindfulness practice typically makes students more comfortable in silence. Effective listening also involves the ability to notice and allow silence:

"I've become much more comfortable with silence in a tutoring session which gives my tutee time to respond to questions or work in silence without feeling rushed or pressured."

The responses indicate that mindfulness training might offer tutors inner resources that help them to understand when wait time is needed and to be comfortable with silence. Mindful tutors are better able to understand both what is said and the importance of silence.

Empathy. The last emergent theme to note is an apparent increase in empathy among some tutors. In addition to sharpening awareness about their own feelings and attitudes, they report being more able to extend awareness to empathize with clients.

"[Mindfulness meditation] provides me with a new perspective on how my client may receive my advice."

"[I am] aware of not only my thoughts and actions, but of my clients' thoughts and actions and how they may be feeling at any given time."

"[I] feel more aware of how other people have their own lives and troubles that they set aside to engage in these sessions."

For years in our center, the faculty have been working on ways to increase tutors' cultural sensitivity and ability to connect with clients very different from themselves. I have also added an emphasis on authenticity, asking tutors to find a way to establish rapport without going through the motions, to find a way to make it real. The emergence of this theme of empathy gives another reason to continue studying mindfulness as a possible way to develop these qualities in our tutors.

Experiences from Two Mindful Tutors

As mentioned earlier in the chapter, in order to understand how these themes manifest in tutoring sessions, I interviewed two seasoned tutors who were among the first to engage in mindfulness practice as part of their tutor education course. Rodolfo Barrett, a former peer tutor and graduate assistant, and Maya Chandler, a former peer tutor, offer their in-depth tutoring experiences with mental focus, stress reduction, metacognition, self-regulation, listening skills, and empathy in the following video.

| Figure 5. "Applying Mindfulness in Tutoring Sessions." Video thumbnail of interviews with Maya Chandler and Rodolfo Barrett. January 22, 2018. Source: James Madison University Innovation Services. |

As the video shows, these seasoned tutors have internalized mindfulness as a way to understand and approach tutoring. Rodolfo explains how he mapped the mindfulness meditation framework of "attentional anchors" onto the tutoring context, enabling him to surmount the obstacles of distractions and papers with a wide range of errors. In addition, through the practice, he is able to avoid subconsciously judging writers and rushing to fill silences in sessions. In alignment with empirical research, Rodolfo even feels that the mindfulness practice has helped him manage his own ADHD during sessions.

Maya's experience as a mindful tutor also clarifies some of the potential benefits of this intervention in tutor education. She explains how mindfulness gave her the means to avoid being distracted by surface errors and potential tangents during a session, thereby increasing her tutoring "efficiency." She also highlights a fruitful area of metacognition when she explains how mindfulness increased her awareness and strategic use of her internal talk and reactions when reading a student's paper.

Given the preliminary findings and the empirical data available, results indicate that several reasonable outcomes for a mindfulness intervention can be achieved in a tutor education class: improved metacognitive awareness, self-regulation skills, attention management, and stress management. However, assessing these benefits can be tricky, due to a seemingly infinite number of variables that have the potential to confound results. I addressed confounding variables by assessing the intervention through reflection papers and tutor observations. First, I bookended the class with reflective essays that include a self-assessment of thinking and reflective journal entries, which helped me see evidence of these outcomes as they become part of the student's experience. I saw evidence of change over time; for instance, when students meditate, they can write with increasing detail and nuance about their own thinking, biases, and attention management. A second way I assessed the mindfulness intervention is through tutor observations. In observing sessions, I have been attentive to evidence of metacognitive awareness, self-regulation, and attention management. I observed tutors' insightful reference to their own thinking on a subject and their moves when they work to reset, try a new technique, and/or change the direction of a session when appropriate. I observed tutors who, despite the noise of the room and a barrage of writing errors, remained focused on the most fundamental writing concerns.

For Tutor Education Classes

|

| Figure 6. Photo of James Madison University student and a writing center consultant trained in mindfulness. February 13, 2018. Source: Sarah Featherstone Photography. |

One primary concern of instructors who wish to begin incorporating contemplative practice in their classrooms is a concern about expertise and qualifications. I do think it is important for an instructor to have an established meditation practice and to have spent significant time as a student of meditation in classes or retreats. The ideal scenario would be for an instructor to receive formal teacher training in teaching mindfulness to emerging adults. The Koru Mindfulness Center offers training at least twice a year with the potential to receive certification ("Mindfulness Teacher Certification"). If this is not possible or if an instructor would like to try the intervention sooner, an outside expert can be brought in as a guest speaker. Instructors might investigate existing mindfulness programs on campus or contact the director of the psychology or counseling department at their institution. The guest can introduce the practice and guide a meditation. In subsequent classes or assignments, a guided meditation recording can be used. Additional online guided meditations and instructional materials are also available from established credible programs like the Center for Mindfulness at the UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center or the Koru Mindfulness Center.

Using an Applied Mindfulness Exercise

If mindfulness meditation is introduced in a tutor education class, it is also beneficial to apply mindfulness directly to tutoring. After the midpoint of the semester in the tutor education course, I use an applied mindfulness assignment that brings tutoring and mindfulness practice together. The assignment features a short student essay on one side of a paper and a chart for cataloging different types of mental activity on the reverse side. I instruct them to read the student essay, without turning the sheet over, as if preparing to work with this student in a session. I give brief, minimal context for the assignment: comparative persuasive essay using sources, general help needed. I tell them they can write notes on the page. After 5-10 minutes of letting them read and take notes on this essay, I interrupt the students by ringing a meditation bell (kept hidden so that students are not anticipating it). I ask them to take note of what they were thinking just before the bell rang. To help them understand this metacognitive move, I ask them to "take a selfie of your mind." Then I ask them to turn the essay over, check the boxes that apply in the first open column, and take some brief notes about their mental activity in the checked categories. I encourage them to be honest, and I stress that they will not be graded on their thoughts. When everyone has had time to write, I ask them to return to the essay to continue preparing for a session. After a few minutes, I interrupt them a second time and instruct them to return to the chart. There is space for a third interruption, though I might also interrupt their reflection process itself or interrupt later one-to-one dialogues discussing the essay or the exercise itself.

If mindfulness meditation is introduced in a tutor education class, it is also beneficial to apply mindfulness directly to tutoring. After the midpoint of the semester in the tutor education course, I use an applied mindfulness assignment that brings tutoring and mindfulness practice together. The assignment features a short student essay on one side of a paper and a chart for cataloging different types of mental activity on the reverse side. I instruct them to read the student essay, without turning the sheet over, as if preparing to work with this student in a session. I give brief, minimal context for the assignment: comparative persuasive essay using sources, general help needed. I tell them they can write notes on the page. After 5-10 minutes of letting them read and take notes on this essay, I interrupt the students by ringing a meditation bell (kept hidden so that students are not anticipating it). I ask them to take note of what they were thinking just before the bell rang. To help them understand this metacognitive move, I ask them to "take a selfie of your mind." Then I ask them to turn the essay over, check the boxes that apply in the first open column, and take some brief notes about their mental activity in the checked categories. I encourage them to be honest, and I stress that they will not be graded on their thoughts. When everyone has had time to write, I ask them to return to the essay to continue preparing for a session. After a few minutes, I interrupt them a second time and instruct them to return to the chart. There is space for a third interruption, though I might also interrupt their reflection process itself or interrupt later one-to-one dialogues discussing the essay or the exercise itself.

I refer to this as an "applied mindfulness exercise" because I am using the awareness that students are developing in our meditation training to increase metacognition in a tutoring scenario. The effect of this exercise has not been formally studied, but the reflective discussion we have after the exercise has always been fruitful. The prospective tutors commonly report that they are able to see exactly how their minds wander off task, how they unconsciously judge clients and themselves, and how easily they get distracted by later order concerns. Importantly, they also notice how being interrupted the first time causes them to be more focused at subsequent interruptions. The first interruption seems to jump start their awareness, or perhaps worry, about wandering off task or working inefficiently.

Teaching Revisions and Additions

In more recent semesters, I added a home mindfulness practice using one of my guided meditation recordings, a mindfulness journal, and a final reflective writing paper. I recommend including these components to maximize the effectiveness of the mindfulness intervention. One can only take up so much class time in silent meditation. In order to increase the meditation time and potential effectiveness, I moved most of the meditation outside of class. The journal assignment requires them to immediately reflect and free write after each home meditation session. The final reflective writing paper prompts students to assess their experience with meditation over the course of the semester. This Mindfulness Journal Assignment is the subject of a separate qualitative study under review.

Creating Buy-in and Setting Expectations

Although adding meditation to a university course is becoming more common, it still may be a shocker for some students. Co-authors Rudy and Maya provided their experience of overcoming an initial skepticism about mindfulness meditation in a tutor education course in the following video.

| Figure 7. "An Initial Skepticism" Video thumbnail of interviews with Maya Chandler and Rodolfo Barrett. January 22, 2018. Source: James Madison University Innovation Services. |

Rudy and Maya were initially skeptical when meditation was introduced as part of their tutor education course. However, the evidence-based approach taken, which includes readings and videos by neuroscientists, psychologists, and other empirical researchers, helped them see beyond popular myths and misunderstandings about meditation. This created the initial buy-in or at least a suspension of judgment needed to give the practice a chance. With regular meditation practice in and outside of class, the skepticism and discomfort are further reduced by direct, personal experience of the benefits. The last level, as both Rudy and Maya indicate, is that, even without a lot of prodding, tutors begin to experience the benefits of mindfulness in tutoring sessions and in their personal lives. In reading hundreds of mindfulness journal entries from other students in the tutor education courses, I have seen Rudy and Maya's descriptions of their movement, from skepticism to integration, become the norm.

As I mentioned earlier, I recommend using a combination of articles and videos to help demystify meditation, relieve discomfort, and increase student motivation. Introduce this material after the students have had a few meditation sessions in order to avoid having expectations color their initial encounters. For many students, the experience of meditation is very new and contrasts with ideas they may have inherited from media or peers. By throwing them in without preparation, you can get a pure response. Students have room to be surprised by their experience. The supplemental materials can then help them move beyond initial impressions and confusion.

Considering the culture of your institution and your student demographics, you can adjust the supplemental materials as needed. For instance, if you are situated in a private, religious institution, you may need to provide materials stressing the scientific, secular nature of the practices. To help students see meditation in more practical terms, I recommend using a video of neuroscientist Amishi Jha's keynote address from the 2012 Mindfulness in Education Network Conference. In that talk, she offers hard data and even FMRI brain scans that show the effects of mindfulness meditation on learning.

In order to counteract students' perception that meditation is simply a stand-alone assignment that does not connect directly with the course material, I recommend including materials that offer a broader context for the metacognitive skills developed through mindfulness meditation. Have the students take Carol Dweck's online mindset test ("Test Your Mindset"), watch her TED Talk, and then reflect on the implications of mindset for tutoring. This gives them a sense of the power of their thoughts and the importance of mindful awareness. Prospective tutors can then see how deeply-entrenched mental habits and constructs influence, and quite often limit, the way students approach writing tasks.

Lastly, because a course syllabus serves as a contract with students and the place where expectations are often set, I advocate including an explanation of the use of meditation in the course.

Conclusion

This study of the integration of mindfulness meditation and practice into writing tutor education offers a glimpse of this intervention's potential in future courses and in research. Given the findings and the rapidly growing body of mindfulness research coming from institutions all over the world, I see the possibility of an emerging area of writing center scholarship, ripe for scholarly investigation and pedagogical innovation.

At our writing center at James Madison University, I see the effects of mindfulness practice on each new cohort that comes through the tutor education course. I see how they arrive on the first day of class nervous, scattered, and unsure of themselves. I see their eyes widen as I bring out the meditation bells and tell them what we're going to do. After the first meditation, I notice a settling in the room, a tangible quieting, and the pleasant shock of this new experience. As the weeks pass, I see the shift from scattered and preoccupied to focused and calm become familiar to them. The moment I lift the bells from the table, eyes are closed, phones are away, and bodies are completely still. Over time, at our writing center, I've seen the way mindfulness has become part of the way we think and talk about tutoring, how it has emerged as one of our organizational values, how it is possible and worthwhile to develop a community of mindful tutors.

Works Cited

American College Health Association. National College Health Assessment, 2017, www.acha-ncha.org/docs/NCHA-II_SPRING_2017_REFERENCE_GROUP_DATA_REPORT.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan. 2018.

AsapSCIENCE. "The Scientific Power of Meditation." YouTube, YouTube, 18 Jan. 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Aw71zanwMnY.

Bamber, Mandy, and Joanne Schneider. "Mindfulness-Based Meditation to Decrease Stress and Anxiety in College Students: A Narrative Synthesis of the Research." Educational Research Review, vol. 18, Dec. 2015. ResearchGate, doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2015.12.004.

Beaumont, Chris, et al. "Easing the Transition from School to HE: Scaffolding the Development of Self-Regulated Learning through a Dialogic Approach to Feedback." Journal of Further and Higher Education, vol. 40, no. 3, May 2016, pp. 33150. CrossRef, doi:10.1080/0309877X.2014.953460.

Bromley, Pam, et al. "Transfer and Dispositions in Writing Centers: A Cross-Institutional, Mixed-Methods Study." Across the Disciplines, vol. 13, no. 1, Apr. 2016.

Cahill, Lisa, et al. "Developing Core Principles for Tutor Education: Administrative Goals and Tutor Perspectives." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson, and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Cahilletal.html.

The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. Our History. 2015, http://www.contemplativemind.org/about/history.

The Center for Koru Mindfulness. "About Koru Mindfulness for College Aged Students." 1 June 2017, http://korumindfulness.org/about/who-we-are/.

The Center for Koru Mindfulness. "Where Is Koru Mindfulness Being Taught?" , 1 June 2017, http://korumindfulness.org/koru-mindfulness-teaching-locations/.

"Center for Mindfulness UMass Medical School." University of Massachusetts Medical School, 9 Sept. 2014, https://www.umassmed.edu/cfm/.

Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and National Writing Project. Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing. CWPA, NCTE, and NWP, 2011, wpacouncil.org/files/framework-for-success-postsecondary- writing.pdf.

Davis, Daphne M., and Jeffrey A. Hayes. "What Are the Benefits of Mindfulness? A Practice Review of Psychotherapy-Related Research." Psychotherapy, vol. 48, no. 2, 2011, pp. 198208. Crossref, doi:10.1037/a0022062.

Driscoll, Dana, and Jennifer Wells. "Beyond Knowledge and Skills: Writing Transfer and the Role of Student Dispositions" Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, http://compositionforum.com/issue/26/beyond-knowledge-skills.php.

Dweck, Carol S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Ballantine Books, 2007.

Dweck, Carol. "The Power of Believing That You Can Improve." TED: Ideas Worth Spreading, 2014, www.ted.com/talks/carol_dweck_the_power_of_believing_that_you_can_improve.

Eckel, Malcolm David. Buddhism. The Teaching Company, 2001.

Earles, Tom, and Leigh Ryan. "Teaching, Learning, and Practicing Professionalism in the Writing Center." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/EarlesRyan.html.

Greeson, Jeffrey M., et al. "A Randomized Controlled Trial of Koru: A Mindfulness Program for College Students and Other Emerging Adults." Journal of American College Health, vol. 62, no. 4, 2014, pp. 22233. PubMed Central, doi:10.1080/07448481.2014.887571.

Gynnild, Vidar, et al. "Identifying and Promoting Self-regulated Learning in Higher Education: Roles and Responsibilities of Student Tutors." Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, vol. 16, no. 2, May 2008, pp. 14761. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.1080/13611260801916317.

Hacker, Douglas, et al. "Writing Is Applied Metacognition." Handbook of Metacognition in Education, Jan. 2009, pp. 15472.

Hφlzel, Britta K., et al. "Mindfulness Practice Leads to Increases in Regional Brain Gray Matter Density." Psychiatry Research, vol. 191, no. 1, Jan. 2011, pp. 3643. PubMed Central, doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006.

Jankowski, Tomasz, and Pawel Holas. "Metacognitive Model of Mindfulness." Consciousness and Cognition, vol. 28, Aug. 2014, pp. 6480. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.concog.2014.06.005.

Jha, Amishi. "Improving Attention and Working Memory with Mindfulness Training." Vimeo, 6 April 2012, vimeo.com/39906585.

Jones, Meadow. "To Write What You Know: Embodiment, Authorship, and Empathy." Sensoria: A Journal of Mind, Brain & Culture, vol. 10, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 4956.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. Full Catastrophe Living. Random House, 1990.

. "Some Reflections on the Origins of MBSR, Skillful Means, and the Trouble with Maps." Contemporary Buddhism, vol. 12, no. 1, May 2011, pp. 281306. CrossRef, doi:10.1080/14639947.2011.564844.

Killingsworth, Matthew A., and Daniel T. Gilbert. "A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind." Science, vol. 330, no. 6006, Nov. 2010, p. 932. PubMed, doi: 10.1126/science.1192439.

Lavelle, Ellen, and Nancy Zuercher. "The Writing Approaches of University Students." Higher Education, vol. 42, no. 3, 2001, pp. 37391.

Mindset | Test Your Mindset. https://mindsetonline.com/testyourmindset/step1.php. Accessed 8 June 2017.

Murray, Deborah. "Zen Tutoring: Unlocking the Mind." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 27, no. 10, June 2003, pp. 1214.

Nilson, Susan. Creating Self-Regulated Learners: Strategies to Strengthen Students' Self-Awareness and Learning Skills. Stylus, 2013.

Poon, Alvin, and Sharon Danoff-Burg. "Mindfulness as a Moderator in Expressive Writing." Journal of Clinical Psychology, vol. 67, no. 9, Sept. 2011, pp. 88195. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1002/jclp.20810.

Rinpoche, Chφgyam Trungpa. "The Four Foundations of Mindfulness." Lion's Roar, 30 Nov. 2016, https://www.lionsroar.com/the-four-foundations-of-mindfulness/.

Rogers, Holly, and Margaret Maytan. Mindfulness for the Next Generation: Helping Emerging Adults Manage Stress and Lead Healthier Lives. Oxford UP, 2012.

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. Bedford/St. Martin's, 2016.

Salmon, Paul G., et al. "Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction." Acceptance and Mindfulness in Cognitive Behavior Therapy, edited by James D. Herbert and Evan M. Forman, John Wiley & Sons, 2011, pp. 132β63. Wiley Online Library, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118001851.ch6/summary.

Schick, Kurt, et al. "The Idea of a Writing Center Course." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 34, no. 9/10, 2010, pp. 16.

Spohrer, Erika. "From Goals to Intentions: Yoga, Zen, and Our Writing Center Work." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 33, no. 2, Oct. 2008, pp. 1013.

UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center. Free Guided Meditations, marc.ucla.edu/mindful-meditations, Accessed 30 May 2017.

UC San Diego Health. Home Practice Materials : MBSR Course, health.ucsd.edu/specialties/mindfulness/programs/mbsr/Pages/homework.aspx. Accessed 7 June 2017.

van den Boom, Gerard, et al. "Effects of Elicited Reflections Combined with Tutor or Peer Feedback on Self-Regulated Learning and Learning Outcomes." Learning and Instruction, vol. 17, no. 5, Oct. 2007, pp. 53248. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.09.003.

Wald, Hedy S., et al. "Promoting Resiliency for Interprofessional Faculty and Senior Medical Students: Outcomes of a Workshop Using Mind-Body Medicine and Interactive Reflective Writing." Medical Teacher, vol. 38, no. 5, May 2016, pp. 52528. EBSCOhost, doi:10.3109/0142159X.2016.1150980.

Weimer, Maryellen. Enhancing Scholarly Work on Teaching and Learning: Professional Literature That Makes a Difference. Jossey-Bass, An Imprint of Wiley, 2006.

Zimmerman, Barry J. "Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview." Theory into Practice, vol. 41, no. 2, 2002, pp. 6470.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank JMU Innovation Services for filming and editing the video content in this chapter, colleagues Kurt Schick and Laura Schubert for supporting our project, and all JMU writing consultants for contributing to this work.

BIO

Jared Featherstone (feathejj@jmu.edu) directs the University Writing Center and teaches in the School of Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication at James Madison University. He is a certified meditation teacher through The Center for Koru Mindfulness.

Rodolfo "Rudy" Barrett (rorudo@gmail.com) is currently a professional consultant at the James Madison University Writing Center. He has previously worked as a peer consultant, graduate teaching assistant, and first-year writing instructor at JMU.

Maya Chandler (maya.chandler.11@gmail.com) is a graduate student studying Architecture at the University College London. After four years as a peer consultant at the James Madison University Writing Center, she graduated in 2017 with degrees in writing and architectural design.