CHAPTER NINE

Exploring and Enhancing Writing Tutors'

Resource-Seeking Behaviors

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Crystal Conzo

Shippensburg University

Background

Over a span of five years, I worked as a peer writing tutor, writing fellow, and graduate assistant (GA) at the Shippensburg University (Ship) Writing Center. The writing center Director, Dr. Karen Johnson, doesn't have faculty or staff who directly support her, so she takes all the help she can get from her GAs—especially those of us who already have writing center experience. Together the four GAs function as one assistant director; therefore, I am one-fourth an assistant director.

|

| Figure 1. One-fourth an assistant director. |

My role as one-fourth an assistant director combined with the positions that preceded it have given me the opportunity to learn about the center from the inside out. I've done it all—from tutoring developmental writers to assisting in the hiring process. Because I'm familiar with the center and its operations, I know we don't have the means to hire tutors who specialize in writing for each discipline—as is the case with many writing centers. Instead, we endeavor to recruit tutors from a range of disciplines, though many potential tutors are busy in other professional development roles, and the most popular disciplines for which students seek writing assistance vary from semester to semester. Even so, our scheduling system and limited tutor hours make it difficult for writers from specific courses to be paired with tutors from corresponding majors. For these reasons, our writing tutors are generalists who provide feedback on writing assignments from courses across the disciplines. Our writing tutors, then, are selected for their expertise in writing and their perceived ability to tutor a diverse pool of writers at any stage of the writing process, regardless of a writer's course of study. This is true of both our regular writing tutors—or writing process tutors as we call them—and our Communication/Journalism—or Media Writing—tutors.

Media Writing, a Communication/Journalism course that focuses on the study of grammar and mechanics in Associated Press (AP) Style writing, is one course of study that is highly represented among the students who come to our writing center. Years ago, in response to departmental requests for support, we implemented a specialized tutoring program for Media Writing. As part of this program, students in the course take a pretest during their first week of classes to determine whether they will be required to attend tutoring sessions to help them learn difficult grammar and mechanics concepts. Students are graded solely on the number of tutoring session attendance reports recorded by the tutor. These tutoring sessions are meant to help students perform better on the proficiency exam, or posttest, they'll take later in the semester. Students who score below a 70 percent are required to attend tutoring. In Media Writing tutoring, the tutor's role is to guide the writer through the process of reviewing grammar, mechanics, and AP Style concepts and to practice these concepts in their writing.

Practice is a must. As Bryan Dugan writes in his article "12 Persnickety Rules from the Associated Press Stylebook," the AP Style editors aren't "messing around." The rules can be particular—or "persnickety" as the title denotes. Some rules from Working with Words, the AP Style Manual used by the Ship Comm/Journ Department, are listed below:

- "Ages. Always use numerals, even for days or months: 3 days old; John Burnside, 56" (Brooks et al. 401).

- "Decades: the 1990s, the '90s, the early 2000s" (401).

- "Dimensions, heights: the bedroom is 8 feet by 12 feet, the 8-by-12 bedroom; the 5-foot-6-inch guard (but no hyphen when the word modified is one associated with size: 3 feet tall, 10 feet long)" (401).

- "Distances. Use figures for 10 and above; spell out one through nine: She walked six miles; they walked 16 miles" (401).

- "Money. Always use numerals, but starting with a million, write amounts like this: $1.4 million" (401).

- "Don't abbreviate a month unless it has a date of the month with it: December 2012; Dec. 7; Dec. 7, 2012" (394).

- "Don't abbreviate a state name unless it follows the name of a city in that state" (Brooks et al. 396).

In addition to these and other AP Style rules, concepts covered in Media Writing have included active and passive voice, pronoun agreement, subject-verb agreement, phrases and clauses, punctuation, commonly confused words, and abbreviations, among others.

In 2010, the Ship Communication/Journalism department noticed that a majority of students who entered the major faced significant challenges with formal grammar and AP Style. Our director worked with the department to develop a collaborative program in part because it helped tutors hone their grammar and mechanics, which ultimately improves their ability to help writers revise their work across all disciplines. By 2013, our director worked with Media Writing professor Holly Ott to measure the growth between the Media Writing course pretest and posttest that assessed students' proficiency in grammar and mechanics concepts before and after supplemental tutoring. Only students who scored a 70 percent or lower on the pretest were required to attend the supplemental tutoring sessions and, thus, served as the participants in Johnson and Ott's study. A paired sample t-test, t (22)=3.22, p < 0.00 showed that proficiency exam scores for students in all four Media Writing sections were significantly higher than pretest scores in each section. The average pretest score (across sections) was 66.5 percent, while the average posttest score was 83.1 percent. Therefore, students improved by an average of 23.4 percent. (Johnson and Ott).

|

| Figure 2. Media Writing Course Pretest and Proficiency Exam Scores for Fall 2013 (Johnson and Ott). |

Three years later, in Fall 2016, students continued to improve as a result of Media Writing Tutoring. Those who attended their required tutoring sessions improved their proficiency exam scores by an average of 23.2 percent, while those who did not attend tutoring improved by an average of 7.9 percent. All students who attended their required sessions passed the course (Johnson). For more information about the Media Writing Tutoring program outcomes, see "Writing Tutoring Boosts Skills and Confidence."

Because our tutors are generalists who may or may not have taken the Media Writing course, to prepare for Media Writing tutoring, we require tutors to take a grammar, mechanics, and AP Style "proficiency exam." The purpose of the exam is to help them better understand which concepts they'll need to review. We also provide an initial workshop to educate tutors on how to use the various learning resources we provide in our center to help writers review grammar, mechanics, and AP Style concepts; validate their claims; and model appropriate behaviors for learning and referencing these concepts. Tutors are encouraged to suggest additions to the resources we provide, but until such resources are approved, we ask they not be used in a tutoring session. We've adopted this policy because in the past when we hadn't specified which resources tutors should use, they sometimes chose blogs, wiki pages, outdated websites, or websites created by unqualified persons, and then communicated inaccurate information to writers.

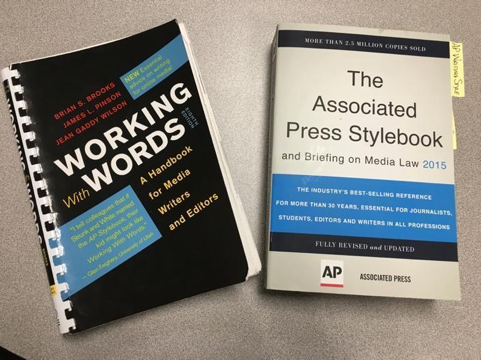

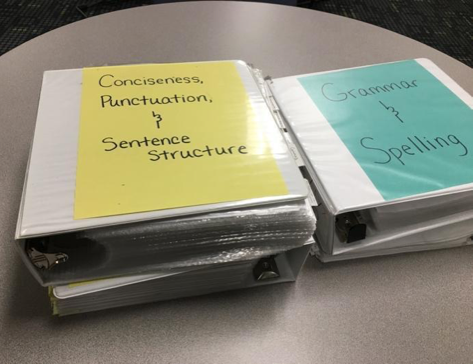

The approved resources, mostly provided by our writing center team and professors, include certain exercises and concept overviews from websites, such as Purdue OWL, Grammar Bytes, The Writing Center at UNC Chapel Hill, Writing and Reporting for the Media, Inside Reporting: A Practical Guide to the Craft of Journalism, and Khan Academy. The electronic resources are available as links on our web site. We also encourage the use of print resources such as Working With Words, The Associated Press Style Book materials provided by professors, and exercises and overviews our writing center team has printed from websites and placed in binders. Additionally, because there appear to be no free online resources that wholly fit our Media Writing course context—meaning there's no one free resource that follows every AP Style rule and offers practice (or enough practice) for every rule the professors cover—our writing center created basic exercises for each of the most popular Media Writing topics and placed them in a binder of its own.

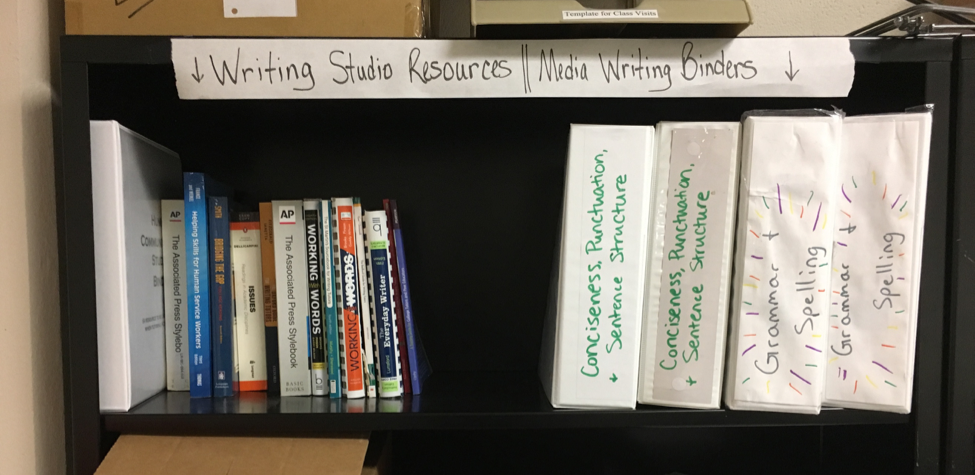

To review, we offer:

- A list of links on our website that leads to exercises and overviews

- Handbooks (see Figure 3)

- Two identical binders with spelling and grammar exercises and overviews (see Figure 4).

- Two identical binders with conciseness, punctuation, and sentence structure exercises and overviews (see figure 4).

- One electronic file—used to be binder—developed by the GAs, with exercises created from scratch and grammar concept overviews that correspond to those in the Working With Words handbook.

|

|

|---|---|

| Figure 3. Working With Words and The AP Stylebook. | Figure 4. Media Writing Binders. |

Writing tutors learn about the many resources the writing center provides (see Figure 5) before their first week of tutoring. We don't expect tutors to memorize all information, but we ask that during their vacant tutoring hours they become familiar with these resources.

|

|---|

| Figure 5. Resource shelf. |

Because of the time it takes for tutors to learn grammar, mechanics, and AP Style concepts, resources for Media Writing become an absolute necessity, as does the reliability of the resources tutors use. Though we emphasize use of resources in Media Writing sessions, we encourage their use in writing process sessions, as well. We strongly believe resources enhance tutoring sessions for Media Writing and writing process sessions, alike. But if it weren't for Media Writing—a course that essentially requires the use of resources—we probably wouldn't have taken as much notice of our developing problem in tutors' resource-seeking behaviors.

The Issue

In Writing Center Studies, professionals often share resources they've developed or compiled for tutors to use with writers. As an example, Diigo Groups, a collaborative research and learning tool, hosts The WLN Writing Center Online Resource Database where more than one hundred educators have shared their instructional and learning resources with other Writing Center Studies professionals. Also, Leigh Ryan and Lisa Zimmerelli explicitly note the usefulness of resources in writing center sessions in The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors: "have print and online resources—like a dictionary, thesaurus, and grammar handbook—readily available" (12).

Furthermore, part of our mission as Writing Center professionals is to create a learning environment for writers that fosters writers' independence. One way to help writers learn and foster their independence is for tutors to consult useful resources and show writers where to access them and how to effectively use them. For this reason, tutor education should address the use of sound resource-seeking behaviors in writing center sessions, which can contribute to successful learning outcomes. In my one-fourth an assistant director role, part of my responsibility is to assess the Media Writing tutoring program. I observed tutors, collected data, communicated with faculty, and interpreted Media Writing students' survey responses. I also observed writing process tutors and provided feedback to them, as well. While observing tutors, over time I noticed some of them weren't accessing resources in Media Writing and/or writing process sessions. Some tutors were using unapproved, unreliable resources or weren't using resources at all, which can limit their credibility and the accuracy of information they share. I've seen, for example, tutors

- relay false information because they feel overly confident in their knowledge of AP Style

- use Google to research topics they are unfamiliar with

- access a single resource repeatedly when better resources are available

- select websites without evaluating their reliability or validity to students' work.

Some of these students' observations were reinforced through Media Writing class survey feedback on their experiences with tutoring:

- "None of them actually knew AP style and journalistic writing. They were kind of Googling as we went along. I think they should already know the rules and be better educated" ("Media Writing Survey Fall 2016").

- "Sometimes they contradicted themselves to what the book said."

- "Half of the time they would not know the answers. They would look on Google, which is something anyone can do" ("Media Writing Survey Fall 2016").

- "It was not cool for me to ask a question and have my tutor just search all over the internet... I could have done that" ("Media Writing Survey Spring 2016").

- "My tutor acted like I didn't need to be there. He used the internet for everything and 'taught' me things that I know were wrong..."

- "I would advise them to really know their material and not half know it, because at times that could get confusing when I knew the correct answers opposed to them."

- "I walked away feeling more confused than when I entered" ("Media Writing Survey Spring 2016").

There was also a disparity between tutors' use of resources in Media Writing sessions and their use of resources in regular writing sessions. Some tutors practiced sound resource-seeking behaviors for Media Writing tutoring, but not for writing process tutoring, or vice versa.

From what I've observed, our tutors generally understand they must access resources to find new information and reinforce what they already know, but problems occur in both Media Writing and writing process sessions when tutors accrue what they believe to be "enough" knowledge and henceforth decline to add more to their existing repertoire, rely on only one or two resources, use unreliable resources, and Google search resources.

Examining the Literature

One reason we discourage our tutors from searching for new resources during their tutoring sessions is their potential lack of expertise in assessing the reliability and validity of web-based information related to the course context. When Nancy Becker set out to examine students' web searching behaviors in an effort to strengthen information literacy programs, she found that to ensure more

accurate search results, students

(and thus tutors) must understand the key concepts and determine the correct keywords to research. Similarly, Claire Warwick et al., in a qualitative study of student information-seeking behavior, found that the students they studied used terms from titles or handouts as opposed to undertaking broader searches of the subject matter and would use familiar tactics—as opposed to developing new strategies—to search for information.

|

| Figure 6. Lost in resources. |

To apply this to the Ship Writing Center context, if a tutor is trying to find an exercise for "he vs. him," they may benefit from a broader search of "subject and object pronouns." However, it's possible tutors will not use broader topics as their search criteria if they aren't familiar with the material or trained to think this way. Information searching requires skill and practice and is in and of itself a learning process (Jansen et al.; Warwick et al.). During a tutoring session, choosing from an approved list on our webpage, looking at a table of contents or browsing through tabs in a binder is helpful in ensuring tutors find and use reliable resources. Furthermore, Tracey Leacock and John Nesbit note that digital learning resources don't always receive expert peer review. The ability to instantly and easily share work with wide audiences via the Internet has sparked rapid growth in the number of electronic learning resources accessible through search engines and repositories. Students, educators, (and tutors) must assess the reliability of the information available. If assessment is undertaken during a 30-60 minute tutoring session, it may leave the tutor strained for time and thus more likely to fudge the assessment process.

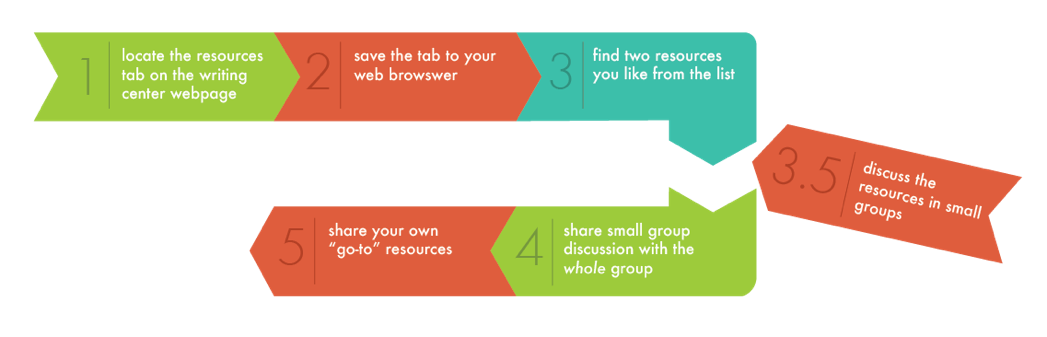

Even if tutors do take the time to assess the value of a resource during a session, there is always the chance that when searching on the spot, they'll overlook something more suitable. Helene Hembrooke et al. conducted a survey of Google search engine users and found that students are inclined to use the topmost search results, neglecting a deep dive into the sources available. The first or second result in a Google search may or may not be useful, and tutors may miss the opportunity to discover and use more effective resources.

|

|---|

| Figure 7. First search result. |

Tutors who don't use resources at all may be sacrificing as much validity as tutors who use inadequate resources. Results of a survey conducted by Soo Young Rieh and Brian Hilligoss , show that students are aware of the importance of the credibility of information sources. Tutors who effectively use resources, then, may be more likely to gain writers' trust and respect. As indicated by our survey feedback, tutors who don't use resources could leave writers confused and doubtful of our tutoring services.

The Research

When I initially noticed a pattern in Google search and inadequate resource use among tutors, I thought they lacked the confidence or motivation to seek out reliable information in times of uncertainty. Thus, I decided to hold a focus group to explore their self-efficacy. Focus group participants included 12 of 13 undergraduate writing tutors from our writing center. Tutors were not aware of the exact purpose of the focus group, only that they would be asked questions regarding tutor education meetings, resources, and collaboration. Each tutor who participated signed a consent form. The focus group discussion was digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. First, I read through the discussion and examined each response. I then created categories for similar responses and coded the responses to correspond with the categories. After the focus group meeting, the issue became clearer. I wasn't interested in self-efficacy but, instead, resource-seeking behaviors specifically. Although I discovered the purpose of my research after the focus group concluded, it was still an interactive and engaging process that helped me productively learn about tutors' practices and perceptions for seeking out and evaluating resources during their sessions. Ten questions were used as guides during the focus group, but only those that led to discussion of research-seeking behaviors are listed below:

- What are some resources [writing center administrators and staff] have introduced that you find helpful to use during your tutoring sessions?

- What is one concept you identified as a concern on your [AP Style] proficiency exam? How did you go about learning it?

- How have our tutor education meetings helped you manage your free tutoring hours?

- How have our feedback forms helped you stay organized?

- How often do you use resources during your writing process sessions? Use your fingers to respond: 1=never, 2=occasionally, 3=sometimes, 4=Often, 5=Every session

- How often do you use resources during your media writing sessions? Use your fingers to respond: 1=never, 2=occasionally, 3=sometimes, 4=Often, 5=Every session

Focus Group Findings

After analyzing the patterns and common responses, I discerned three common themes among tutors. For a theme to emerge, at least three tutors out of twelve had to have taken actions consistent with the category.

Theme #1: The Role Model.

The Role Model uses the writing center approved resources and exhibits sound resource-seeking behaviors. In addition to using resources within the writing center, one tutor noted she employs materials the writers bring from their class sessions: [sound clip]. Class quizzes are especially useful because they reflect the professor's expectations. Another tutor noted she likes to use the binder with exercises created from scratch so that writers can access it beyond the writing center: [sound clip]. A third tutor also considers accessibility and user-friendly format: [sound clip]. These tutors are not only using resources, they're using reliable resources that provide a quality foundation to support their claims.

Theme #2: The Resource.

The Resource tends to rely on their own knowledge rather than accessing or exploring print or digital resources to enhance their knowledge and model best practices for writers: [sound clip]. [sound clip], and [sound clip]. Based on their responses, these tutors may view resources as useful only to novice tutors, not experienced ones, like themselves.

Another tutor noted that she didn't find much value in the feedback form, which is a beneficial post-session resource for writers: "I usually forget about it until the end and then I'm like 'oh yeah we have this thing for you to fill out, too.'" Because the feedback form is completed to help writers after they leave our writing center. On the feedback form, we often provide additional resources for the writer to use to help them in their continued learning. The aforementioned statement, then, suggests that some tutors may not recognize the value in using resources for the writer's benefit, either.

Theme #3: The Googler. The Googler limits their use of writing-center approved resources and/or refers to their own unapproved resources, which may lack reliability and applicability to the writer's work. One tutor noted that she uses Google to find answers: [sound clip]. As mentioned, it's difficult to assess the reliability of resources on the spot. We have the style book to cover at least an overview of the concept, whatever it may be. This tutor realizes that she isn't following protocol, but perhaps because Google has been her default resource-seeking platform for years, this habit can be difficult to break.

Another tutor who is accustomed to a single writing center-approved resource also relied on Google as opposed to exploring other approved resources when he ran out of practice materials: [sound clip] This tutor refers to one AP Style binder, but there are others that offer additional practice. It is always best to browse our approved resources first because they're content-specific and applicable to our institutional context. They've worked in the past, and we know our instructors approve of them.

A third tutor claims to stick with one resource. He also shows inattention to the writing center approved resources: [sound clip]. At the time of the focus group, GrammarBook.com was not an approved resource. In the past, some exercises had significant flaws and some were not applicable to the Media Writing course context. The website has since undergone development, and most exercises are appropriate for use. Ideally, the tutor would have asked us for approval before using this website. In addition, using an approved resource, such as Working With Words, in combination with GrammarBook.com would help to ensure the content is reliable and representative of AP Style.

Encouraging Appropriate Resource-Seeking Behaviors

This study, though limited to the specific group of tutors involved in the focus group, suggests that tutors in our writing center should practice more appropriate resource-seeking behaviors and model them for writers. Tutors vary in their dispositions, so creating learning opportunities can be challenging. But because it is so important for tutors to access reliable resources, I collaborated with the writing center staff to develop solutions. Since the focus group, we've taken more time to familiarize tutors with the resources we provide.

|

| Figure 8. Tutoring session in our writing center. |

To understand the changes we made, it's helpful to know the structure of our center. We have one director, four GAs, approximately 14-15 undergraduate writing process and/or Media Writing tutors, and 8-10 undergraduate writing fellows. The new tutors and fellows attend an all-day new tutor education program at the beginning of their first semester. From thereafter, tutors and fellows attend separate bimonthly mandatory education meetings, each of a different topic.

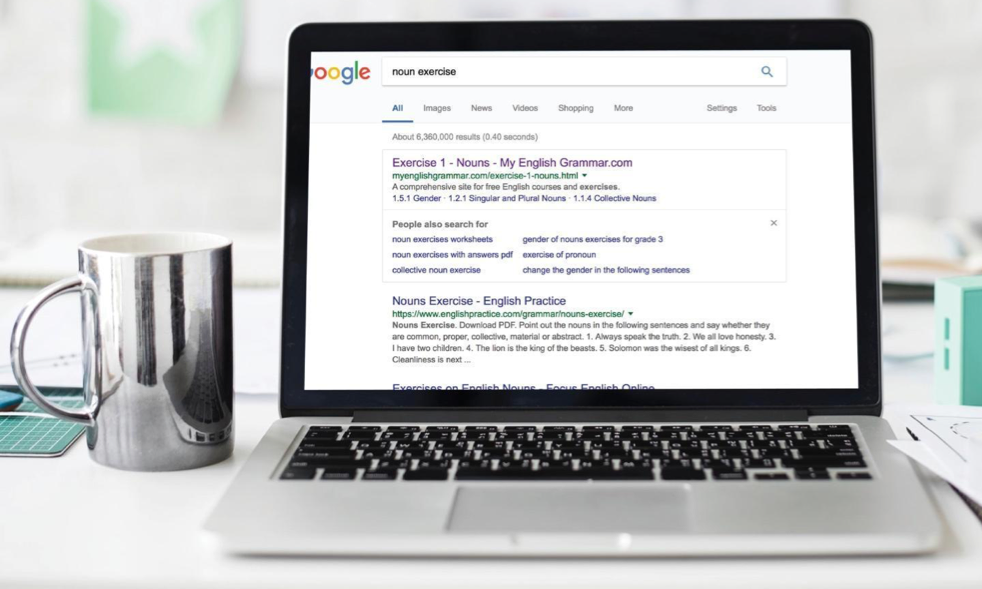

In the past, during our all-day new tutor education program, we asked tutors to locate the resource tab on the writing center web page, save the tab to their web browser, find two resources they like from the list, discuss the resources with the group, and share their own "go-to" web-based resources. As mentioned in the literature review, searching for resources is a learning process, and we have always encouraged tutors to engage in it outside of their tutoring sessions.

|

|---|

| Figure 9. Steps in resource activity. |

To make searching for resources even more interactive, we now have tutors discuss resources in small groups of two before they share with the larger whole. Small group discussion is a useful strategy for increasing participation because some are more comfortable sharing their opinions and experiences with one or two peers, but not with the whole group—which usually consists of participants and facilitators in the double digits. The all-day new tutor training is also the first time these tutors interact with each other, so they're often unsure of themselves and their responses.

|

|---|

| Figure 10. Steps in resource activity revised. |

To create long-lasting effects, we also encourage tutors to write down the information they learn. This step may seem obvious, but sometimes they forget to take notes because we consistently engage them in discussion, and we print paper copies of the presentation slides for them. At the end of the activity, we ask them to describe how they plan to use the resources in their tutoring sessions. Tutors write down their descriptions, which we collect and review to gauge the activity's effectiveness. We also revisit a condensed version of this activity with returning tutors at the beginning of each semester.

Since conducting the focus group, we also make it a point to often re-introduce resources and encourage tutors to use them. We better monitor resource use, as well. At our center, GAs typically observe tutors once each semester, but previously these observations did not occur until mid-semester or later. Our focus group conversations revealed we must make a greater effort to observe new tutors toward the beginning of the semester. Now, after we complete our first observations, we identify tutors who need additional observations and offer support accordingly. We are also careful to pair new tutors with model tutors for peer observations. This practice ensures that new tutors receive appropriate guidance. Also, when GAs perform observations, we commend appropriate resource use and share our own experiences using resources to meet writers' needs.

Since conducting the focus group, we also make it a point to often re-introduce resources and encourage tutors to use them. We better monitor resource use, as well. At our center, GAs typically observe tutors once each semester, but previously these observations did not occur until mid-semester or later. Our focus group conversations revealed we must make a greater effort to observe new tutors toward the beginning of the semester. Now, after we complete our first observations, we identify tutors who need additional observations and offer support accordingly. We are also careful to pair new tutors with model tutors for peer observations. This practice ensures that new tutors receive appropriate guidance. Also, when GAs perform observations, we commend appropriate resource use and share our own experiences using resources to meet writers' needs.

To further encourage tutors to engage in sound resource-seeking behaviors and expand their knowledge, we discuss the benefits of accessing resources during our biweekly education meetings. By using mock tutoring sessions, exercises, videos and experience sharing, we guide tutors to understand that using a variety of resources reinforces their claims and fosters writers' independence. Consistently sharing resources and discussing them with tutors helps to increase their awareness and familiarity.

Lastly, we hold a workshop where tutors create their own resources. Having tutors develop their own AP resources is a way for them to fully process AP style rules and effectively communicate them. Tutors are more likely to use resources that they've invested time and effort into developing. Also, based on personal experience, tutors may feel more prepared to use a self-made resource because they remember the answers and the logic or rationale behind them.

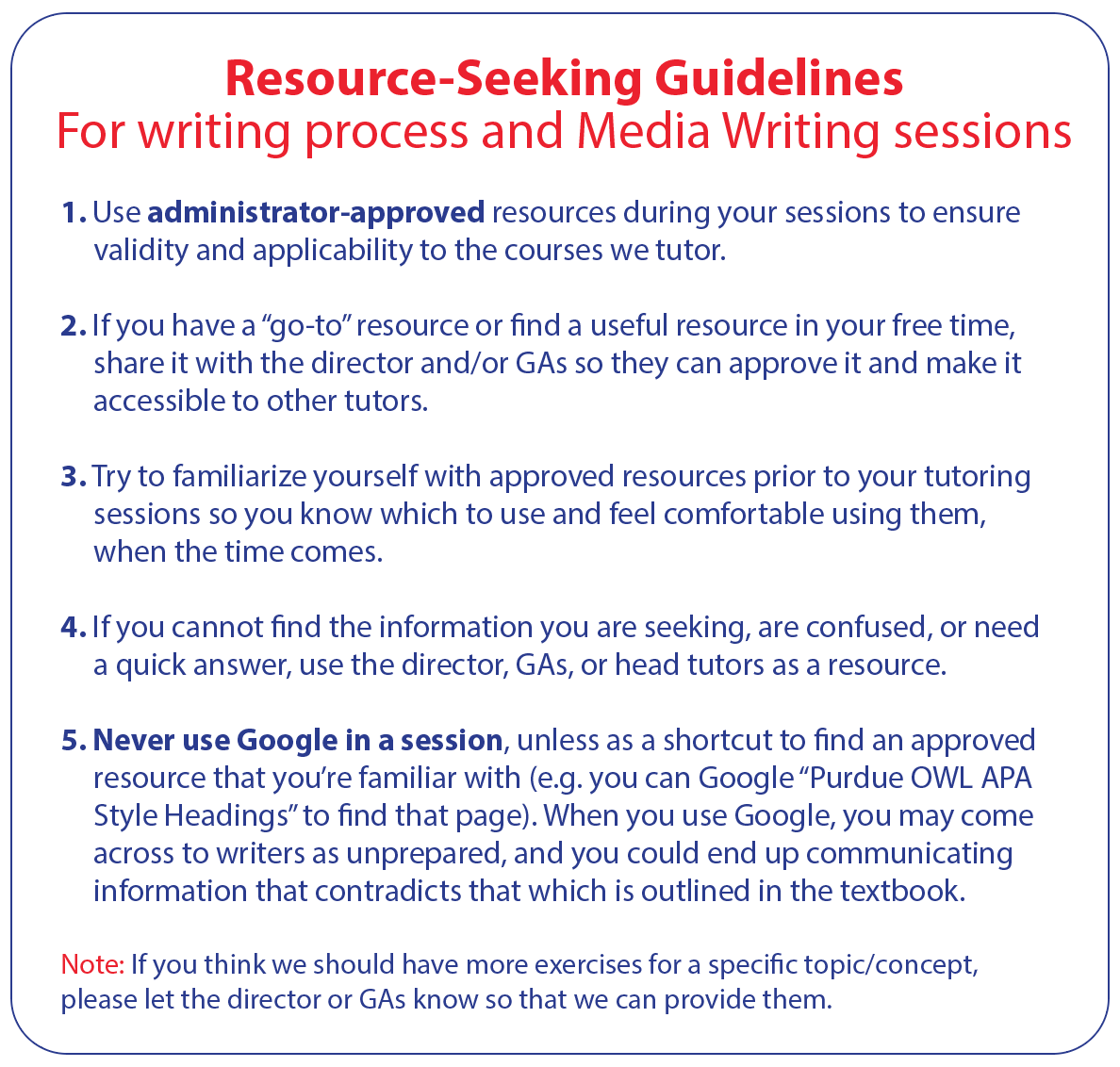

Some Tutor Guidelines for Resource-Seeking Behaviors

Although guidelines for resource-seeking behaviors may vary across writing centers, I've generated a set for our writing center that may serve as a starting point at your center.

|

|---|

| Figure 11. Resource-seeking guidelines for our writing center. |

Beyond Resource-Seeking Behaviors

Though the heart of this study is resource-seeking behavior, the focus group was also valuable in that it gave tutors a platform to express their thoughts and concerns. As Elisabeth H. Buck argues, the focus group approach makes problem-solving dialogic and can function as an "effective source of feedback." In fact, via the end-of-semester survey, the focus group was ranked among tutors as the most effective education meeting of the semester—possibly because tutors had an open discussion with each other without input from the GAs. GAs participated only to facilitate the discussion, and their purpose was to remain completely objective. Participants also sat in a circle with the GAs, which reduced barriers and decreased formality.

The Key Takeaway

A combination of focus group research and idea-sharing has helped our writing center target what we believe to be a weak area. Yes, a handful of tutors at the Ship Writing Center may not consistently access resources to find information and validate their claims, use approved and/or reliable resources, or browse approved resources to increase familiarity. However, allotting extra time to familiarize tutors with resources, monitoring tutors' resource use through observations, and encouraging tutors to expand their knowledge and model best practices for writers will help them improve upon limiting behaviors.

|

|---|

| Figure 12. A long-term relationship with Working With Words. |

We believe lack of resource use or lack of appropriate resource use can be problematic because resources permeate our lives as writing center professionals. And most of the time we use them for the benefit of the writer. In tutoring the writing process, tutors may have to, or wish to, define a subject-specific term, research how to format a table in APA Style, reference a useful video about color coding, use a template to help a writer outline their paper, etc. These activities lead to a dictionary, an APA Style manual, a website, or another resource. It's important for tutors to know which resources exist and which ones will be consistently useful. Instead of going to a different place every time they have the same or similar questions, it makes sense to compile the best resources for specific topics, share them, and use them. This practice is not by any means a new finding; what is new is our understanding that we can benefit from added discussion about sound resource-seeking behaviors. We can encourage tutors to continue to explore resources beyond those that they use frequently, but we like to ensure they spend some time with the resource first before using it in a tutoring session or diving into a long-term relationship.

Works Cited

Associated Press. The Associated Press Style Book. Basic Books, 2015.

Bender, John R., et al. "Writing & Reporting for the Media. 11th ed." Oxford U P, 2019, http://global.oup.com

/us/companion.websites/9780190200886/student/apresources/apquiz/. Accessed 6 Jan. 2019.

Becker, Nancy J. "Google in Perspective: Understanding and Enhancing Student Search Skills." New Review of Academic Librarianship, vol. 9, no. 1, 2003, pp.84-99, https://doi.org/10.1080/13614530410001692059. Accessed 31 March 2018.

Brooks, Brian S., et al. Working With Words: A Handbook for Media Writers and Editors. 9th ed., Bedford/St. Martin's, 2017.

Buck, Elisabeth H. "From CRLA to For-Credit Course: The New Director's Guide to Assessing Tutor Education." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Buck.html.

Dugan, Brian. "12 Persnickety Rules From the Associated Press Stylebook." Mental Floss, 2013. http://mentalfloss.com/article/50346/12-persnickety-rules-associated-press-stylebook. Accessed 1 May 2018.

Harrower, Tim. Inside Reporting: A Practical Guide to the Craft of Journalism. McGraw-Hill, 2019, http://highered.mheducation.com/sites/0073378917/student_view0/index.html. Accessed 6 Jan. 2019.

Hembrooke, Helene, et al. "In Google We Trust: Users' Decisions on Rank, Position, and Relevance." Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 12, no. 3, 2007, pp. 801-23, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00351.x. Accessed 31 March 2018.

Jansen, Bernard J. "Understanding Web Search Via a Learning Paradigm." Journal of the American Society for Information Science, vol. 45, no. 6, 2009, pp. 643-63, https://doi.org/10.1145/1242572.1242768. Accessed 31 March 2018.

Johnson, Karen Gabrielle. Fall 2016 Writing Center Report, 2016. Internal Report.

--. "Media Writing Survey Fall 2016," 2016. Questionnaire.

--. "Media Writing Survey Spring 2016," 2016. Questionnaire.

Johnson, Karen Gabrielle, and Holly Ott. "Creating Synergy." 2013. PowerPoint presentation.

Johnson, Karen Gabrielle, et al. "Writing Tutoring Boosts Skills and Confidence." Academic Exchange Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 1, 2015, http://rapidintellect.com/AEQweb/5554v5.pdf.

Khan Academy. 2019, https://www.khanacademy.org. Accessed 6 Jan. 2019.

Leacock, Tracey L., and John C. Nesbit. "A Framework for Evaluating the Quality of Multimedia Learning Resources." Journal of Educational Technology & Society, vol. 10, no. 2, 2007, pp. 44–59, https://library.educause.edu/resources/2007/7/a-framework-for-evaluating-the-quality-of-multimedia-learning-resources. Accessed 31 March 2018.

Rieh, Soo Young, and Brian Hilligoss. "College Students' Credibility Judgments in the Information-Seeking Process." Digital Media, You, and Credibility, Edited by Miriam J. Metzger and Andrew J. Flanagin, The MIT Press, 2008, pp. 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1162/dmal.9780262562324.049. Accessed 31 March 2018.

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. Bedford/St. Martins, 2016.

Simmons, Robin L. Grammar Bytes! http://www.chompchomp.com/menu.htm. Accessed 6 Jan. 2019.

The Purdue OWL Family of Sites. The Writing Lab and OWL at Purdue and Purdue U, 1995-2018, owl.english.purdue.edu/owl. Accessed 6 Jan. 2019.

The Writing Center. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2019, https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/. Accessed 6 Jan. 2019.

The Writing Studio. Shippensburg University, https://www.ship.edu/learning/writing_studio/. Accessed 6 Jan. 2019.

Warwick, Claire, et al. "Cognitive Economy and Satisficing in Information Seeking: A Longitudinal Study of Undergraduate Information Behavior." Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, vol. 60, no. 12, 2009, pp. 2402-15, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21179, Accessed 31 March 2018.

Glowzenski, Lee Ann, editor. WcORD: The WLN Writing Center Online Resource Database. https://groups.diigo.com/group/wln-resource-archive. 6 Jan. 2019.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I'd like to thank Karen Gabrielle Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck for helping me revise and expand my chapter—a work that originated as a 1500-word tutor's column. I would also like to thank Ship's Writing Center tutors for their willingness to participate in my focus group. Finally, as Digital Editor of this collection, I'm grateful for Steve Johnson, whose images appear in the background of each chapter.

BIOS

Crystal Conzo, M.S., is the Digital Editor for this collection and an Academic Advisor in the Department of Academic Engagement and Exploratory Studies at Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania. She also coordinates the Student Business Plan Competition for Pennsylvania's State System of Higher Education.