CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Learning Online to Tutor Online

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Daniel Gallagher

University of Maryland University College

Aimee Maxfield

University of Maryland University College

Background on the University of Maryland University College

According to the most recent National Census of Writing (2015), over 30% of institutions surveyed (n=609) provide some form of synchronous online writing support. Over 38% provide some form of asynchronous online writing support. The means by which these schools deliver online writing support varies considerably, from platforms designed for the purpose (like WCOnline) to software packages adapted for this use (like Adobe Connect) to whatever means are available (like Google Docs and phone calls). The numbers are only likely to increase as more and more students—over one in four at present, according to the Online Learning Consortium—take courses online. For students operating in an online environment, making support services available in the same fashion is vital to their ongoing success. Even for students attending classes face-to-face, allowing the option for online support makes sense as students are researching and writing online.

However, distance education has always had a significant challenge in establishing a sense of co-presence: creating the perception that a student is not alone in the process, despite the fact that the student might not physically interact with another person. Since its founding in 1947, the University of Maryland University College (UMUC) has focused on distance education, specifically serving a large military student population. As correspondence classes gave way to online learning in the late 1990s, UMUC was one of the leaders in transitioning to internet-based classes, and, by extension, online support services. While the military is still heavily represented, the most common shared characteristic of current UMUC students is that they are working adults who take classes when they can, making sometimes slow progress towards a degree. It is all too easy for the student who retreats to the basement for coursework after putting the kids to bed or the deployed service member completing assignments after fulfilling assigned duties to perceive she is engaging in a solitary venture.  Fellow students, and even instructors, can seem no more than words on a screen. To support these students, the UMUC Effective Writing Center (EWC) has been exclusively online for over a decade, making concerted efforts to change that perception through operational practices, written structures, and multimedia tools.1 Embracing the online environment presents opportunities to mediate the challenges of working with students from a distance, and our tutor education program focuses on taking advantage of those opportunities.

Fellow students, and even instructors, can seem no more than words on a screen. To support these students, the UMUC Effective Writing Center (EWC) has been exclusively online for over a decade, making concerted efforts to change that perception through operational practices, written structures, and multimedia tools.1 Embracing the online environment presents opportunities to mediate the challenges of working with students from a distance, and our tutor education program focuses on taking advantage of those opportunities.

One of the cornerstones of our tutoring program is our belief that non-real-time interaction can benefit tutor and writer when both are prepared to work and communicate asynchronously in an online setting. While our center offers both synchronous and asynchronous options, asynchronous tutoring makes up the majority (approximately 90%) of our interactions with students and has been offered for a significantly longer period of time. In this section, we will focus first on the details of the asynchronous service and how we educate tutors to deliver that service effectively. In the next section, we will discuss how we provide synchronous online tutoring.

Asynchronous Tutoring at UMUC: Responding to Writing with Writing

Face-to-face tutoring is often regarded as the "gold standard for teaching academic writing" (Angelov and Ganobcsik-Williams 47), largely because it was initially the primary, if not the sole, option for most writing centers. Ben Rafoth writes about the importance of "speaking with someone one-on-one, where facial expressions, enunciations, gestures...[make] us feel alive and energized" ("Why Visit Your Campus Writing Center?" 146), and Muriel Harris has suggested that asynchronous (email) tutoring can be "cold" and "limiting" (7). However, Beth Hewett identifies several major advantages of asynchronous online tutoring, pointing out that it supports students with less traditional schedules, gives both tutor and student additional time to read and consider drafts and advice, functions as a reference for future use, and offers a sense of privacy that might not be present in a face-to-face setting (31-32). In addition, digital communication—email, social media, texting—has become firmly integrated in many writers' everyday lives, and distance learning continues to grow in popularity. Consequently, students (and tutors) are much more equipped than they were even a decade ago to communicate in this medium. They are already primed to manage the challenges and take advantage of the benefits of the online setting. When a tutor is well-prepared to develop analyses and advice tailored to the writer, written feedback facilitates and supports this interaction.

At the EWC, tutors respond to students in stand-alone advice letters, rather than embedding comments in students' texts. Our rationale is that creating a personalized, persuasive, logically organized advice letter allows the tutor to both model effective writing and establish a connection with the student within the boundaries of a written text. Certainly, arguments exist for both methods. Beth Hewett advocates writing feedback that makes use of both an advice letter as well as limited embedded comments, but she emphasizes the importance of making sure that these are unified; if the "embedded comments appear to contradict the global, overarching comments," a student could potentially misinterpret the advice (65). Rafoth points out that when emphasis is on embedding very directed comments in a text, the resulting advice may lack focus and a sense of prioritization, and the tutor's tone can be difficult for the writer to discern (152). Our format still allows the tutor to address very specific passages, just as embedded comments do, by copying and pasting them into the advice and making them an integrated part of a more global discussion. Students then view these comments in the context of the advice, where they are organized by the aspect of writing being addressed. The goal is to give the student a realizable, coherent revision plan, which can be more difficult with embedded comments that are dependent for their organization on the student's own structure. Finally, an independent piece of advice, focused on the student's own writing and targeting both strengths and areas for revision, helps the student to practice the critical reading skills so closely related to writing development.

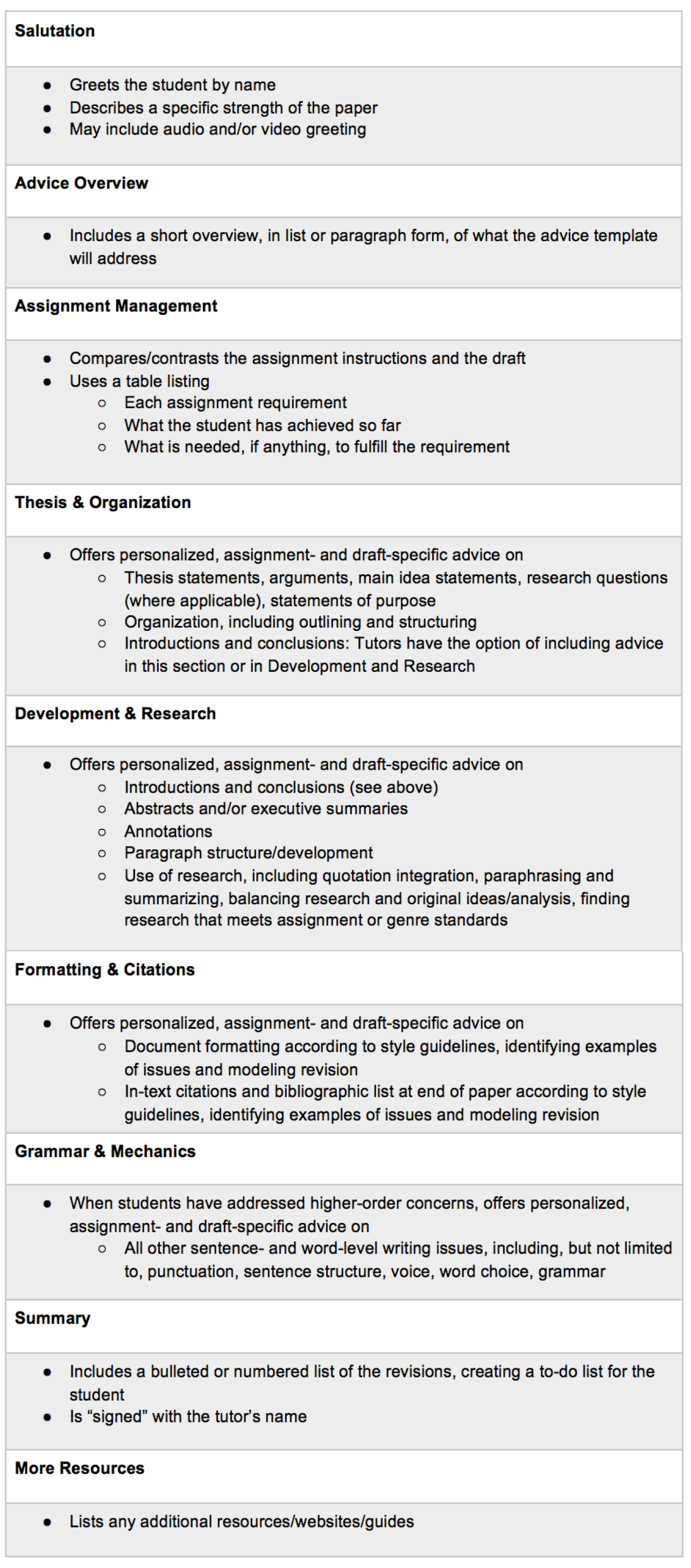

Our advice letters use a standard template with section headings; the template is designed to help the tutor prioritize revisions and emphasize process, both implicitly in the structure of the letter and explicitly in the discussion of specific methods, as well as establish and maintain a tone customized to the student's writing experience and concerns. Tutors determine the main objectives of the revision process. Although the standard template format ensures consistency among advice letters, emphasis will vary based on the student's request and the tutor's analysis of needs. Certain sections may be brief and focused on relatively minor revisions or a discussion of how the student has successfully met certain goals. In the case of early drafts or when a student requests help getting started on an assignment, the tutor has leeway to tailor the advice and recommend that students focus on higher-order revisions until the draft is more complete.

In addition, unlike a face-to-face meeting, the written format allows the student to take breaks and work on certain revisions before going back to the tutor's advice. A student might develop the argument or work on organization during one sitting, and then refer back to the advice hours or days later to address additional issues. This not only helps support the busy and often unpredictable schedules of UMUC students, it also allows students who might feel overwhelmed by a lot of text to read and consider the advice at their own pace. Figure 1 offers a break-down of the standard template sections.

|

| Figure 1. Advice letter template sections. |

Within the advice template, there's ample opportunity for customization and personalization, not just to the writer's needs, but to the tutor's own personality, style, and revision methods. Every interaction is an opportunity to model both higher- and lower-order concerns, and the interval between a student's submission and a tutor's reply helps to ensure that the advice is constructive and customized to the writer's specific needs. Lee Ann Kastman Breuch and Sam Racine explore the advantages of the lack of immediacy in asynchronous "text-only" tutoring, pointing out that "the delay provides opportunity for reflection, consideration, and unlike in face-to-face tutoring, an opportunity to edit and take back words," allowing tutors to produce "careful, well-considered responses" (248). In our experience, tutors appreciate the chance to rework and rethink the focus of their advice; often the goals of a student's assignment or areas for revision are much clearer upon a second reading. Revision can benefit the advice as much as it does the original writing.

Furthermore, because advice letters to students are archived in our database, tutors are able to review past advice and prioritize concerns in their current advice. Most face-to-face centers archive notes from or summaries of previous meetings, which helps tutors to ensure continuity and consistency among meetings. Tutors (and administrators) can get a sense of a student's individual developmental arc. When a tutor references past advice ("Last time, we focused on X: you're showing improvement there, so let's focus on Y"), a student also gains greater appreciation for her progress and how writing ability develops over time. Referencing these past interactions within the advice creates something akin to a dialog between tutor and student. In an online asynchronous setting, the advice is effectively the whole interaction; even if a tutor only has time to skim previous advice, he or she has access to everything the last tutor discussed. More importantly, perhaps, so does a student, and the advice exists as a resource "endlessly available to a student who uses it for revision" (Hewett 92). Tutors are taught to take advantage of the information available to them, not only to further personalize the advice and contribute to learning development, but to better establish the sense of co-presence that is vital to online education as well as to create advice that will be valuable to students in both current and future assignments.

The permanence of the advice is one significant benefit to tutoring online. Rather than relying on notes and memory, students are in possession of an object: written and multimedia resources in the case of an asynchronous session; a written summary and a recording in the case of a synchronous session. Because the advice is an object that becomes a student's own, the resources included in the advice can be referenced at any point, allowing a student to build a personal library of supplemental material over time. Three sample advice letters can be found in Appendices A, B, and C to this chapter, demonstrating the features discussed. These advice letters were created by one of our long-time tutors, whose work we frequently hold up as an example to newer tutors. These advice letters were for students in introductory, intermediate, and upper-level writing courses, from which we typically see a large number of students per term.

Online Tutor Education in Theory

All tutor education at the EWC, both initial and ongoing, is conducted online. There is no formal, for-credit tutor education class, but the process of preparing tutors to work with students can take anywhere from two to six weeks. The tutoring staff is professional rather than peer; moreover, most staff have an established relationship with UMUC, holding degrees, taking classes, or teaching. Our  tutors live, work, and study all across the globe from Texas to Thailand. On one hand, this is simply a function of who we are as an institution. Given UMUC's nature, operating online is not only a convenience but a necessity. Significantly, our tutors' circumstances often closely mirror those of the students with whom they work, allowing for more meaningful interaction and understanding of their experiences. While these tutors are not peer tutors in the way writing centers typically use that phrase, their shared experiences of working from a distance meaningfully affect their ability to form connections and understand the specific, sometimes idiosyncratic needs of the students they serve. The experience at UMUC might be unique, but the underlying principle should hold across institutions: in order to work effectively in an online environment, tutors must appreciate the experience of learning online. By receiving tutor education online, tutors can begin to get a sense of what operating online involves for the students they will support.

tutors live, work, and study all across the globe from Texas to Thailand. On one hand, this is simply a function of who we are as an institution. Given UMUC's nature, operating online is not only a convenience but a necessity. Significantly, our tutors' circumstances often closely mirror those of the students with whom they work, allowing for more meaningful interaction and understanding of their experiences. While these tutors are not peer tutors in the way writing centers typically use that phrase, their shared experiences of working from a distance meaningfully affect their ability to form connections and understand the specific, sometimes idiosyncratic needs of the students they serve. The experience at UMUC might be unique, but the underlying principle should hold across institutions: in order to work effectively in an online environment, tutors must appreciate the experience of learning online. By receiving tutor education online, tutors can begin to get a sense of what operating online involves for the students they will support.

Breuch and Racine point out that in addition to fostering students' writing skills, "text-only environments...encourage tutors to write in the ways that writing centers promote" (248). Hewett concurs, emphasizing the importance of tutors "learn[ing] how to write about writing" and using the language of writing in order to communicate "writing conventions, instructional expectations, and how to achieve both" (98). Our education program for new writing tutors begins and concludes with tutors reviewing actual student essays from our archives, writing advice into our template form, and receiving feedback from the tutor education coordinator. These practice reviews ensure that new tutors are equipped to converse about writing—using "vocabulary specific to writing instruction" (Hewett 98)—and to contextualize the advice in a structured discussion rather than to copy edit or correct. In an online, text-based format, there's a genuine risk of just offering unsupported directives or suggestions if the tutor is not prepared to both identify areas for revision, and explain why, when, and how to apply these revisions to both current and future writing. Our process, with its focus on simulated advice, helps us as educators and mentors gauge tutors' preparedness and, just as our tutors do when working with student writers, identify areas for development and offer strategies for making the advice more effective.

Our rationale for our tutor education process reflects our approach to the student's experience in tutoring: we respond to writing with writing. A good piece of advice mirrors a solid academic argument with effective organization, evidence, and rhetorical structure. This format also has an added benefit when tutor educators evaluate new writing tutors' readiness to work with students. On the most basic level, the benefit involves the means of communication; during tutor education, most interactions between the tutors and coordinator are written and asynchronous. New tutors and the training coordinator may converse via instant messages or a live web conference to solve isolated technical problems if they arise, but our asynchronous tutor education program can be completed without tutor or coordinator ever having a real-time conversation. This allows tutors to become comfortable with the medium, and more specifically, comfortable writing about writing within this medium. By using the processes and simulating the environment of a tutor's and student writer's actual interaction, tutors express that they feel more prepared and confident in this environment.

Our rationale for our tutor education process reflects our approach to the student's experience in tutoring: we respond to writing with writing. A good piece of advice mirrors a solid academic argument with effective organization, evidence, and rhetorical structure. This format also has an added benefit when tutor educators evaluate new writing tutors' readiness to work with students. On the most basic level, the benefit involves the means of communication; during tutor education, most interactions between the tutors and coordinator are written and asynchronous. New tutors and the training coordinator may converse via instant messages or a live web conference to solve isolated technical problems if they arise, but our asynchronous tutor education program can be completed without tutor or coordinator ever having a real-time conversation. This allows tutors to become comfortable with the medium, and more specifically, comfortable writing about writing within this medium. By using the processes and simulating the environment of a tutor's and student writer's actual interaction, tutors express that they feel more prepared and confident in this environment.

Online Tutor Education in Practice

The first activity of our tutor education program requires tutors to review a student's paper from our archives and write a response based on their own preferences, format, and style, without following the Effective Writing Center's own methodology or template. A tutor might write a letter, a list, a paragraph, or anything else that allows her to share suggestions. This gives the tutor education coordinator a kind of baseline, or diagnostic, of a tutor's particular strengths and areas for development. The coordinator responds to this initial feedback, offering suggestions and strategies to help the tutor begin to conceptualize framing advice according to our specific methods. After the coordinator responds, the tutor continues on to a series of self-paced read-and-respond activities before revising the first advice letter and working on additional simulations. We find that all of the tutor education resources we offer—both articles by scholars in the field and materials detailing the EWC's own processes and policies—have much greater context as a result of this introductory exchange. Even if a new tutor has read sample advice letters on our website or in the tutor education space, she will have a clearer sense of the work after writing a rough draft, so to speak, of the type of feedback that our writing center offers.

Although many of our tutors have previous experience teaching or tutoring online, some are transitioning from face-to-face writing center or classroom teaching backgrounds, and during tutor education, we instruct new tutors in strategies for offering structured, personalized, and supportive written advice—a process that might be unfamiliar to them. Writing effective advice is the primary focus of feedback from the tutor education coordinator to article responses and advising simulations. In online work, it is important that we avoid the cold impersonality Harris has cautioned against; we also must ensure that revision advice—the practical strategies, the rationale for them, the supporting resources—is the focal point of the feedback letter. Occasionally new tutors, who are keen to be as friendly and helpful as possible, may be inclined to use positive language in ways that are not ideal for a written document. For instance, the advice might begin by informing a student that she has done a "really good job" or "excellent work," without specifying the nature of it. Although any writer would initially feel pleased and encouraged by this type of statement, she might feel confused and blindsided when the rest of the advice focuses on what she needs to work on. Our goal, therefore, is to always be specific when offering positive reinforcement: "Your argument is effective because," "As a reader, I appreciated the detailed description in this passage, because," "Your in-text citations follow APA format, and this is important to effective writing because," and so on. The tutor augments these comments with quotations from or references to certain parts of the draft, as can be seen in the examples provided in the appendix. Reinforcing effective strategies evident in a student's writing is important, but it loses efficacy as a learning experience without detailed analysis of why the strategies in question work.

Likewise, our new tutors work on writing constructive advice that includes analysis of why suggested revisions will benefit the work. Hewett argues that a "problem-centered lesson," where a tutor points to a specific example from the draft, demonstrates revision strategies, and explains how to identify and revise other instances of the problem or error, personalizes the issue and presents a solution that is both "clear and doable"(105). We have found that investing this kind of approach with a positive tone, and framing the revision as a kind of opportunity, rather than a simple fix, also helps our tutors to balance their own desire to put students at ease with the students' desire to know what to revise and how to revise it. For example, a tutor might write, "As you continue to work on the paper, I recommend double-checking the formatting of some of your References citations. This way, you can make sure that you're meeting all APA guidelines, which helps you to establish your credibility as a writer and meet your assignment requirements." A tutor could then follow this by copying and pasting an incorrectly formatted citation from the draft, demonstrating how and why to revise it, and offering strategies for identifying and revising other citation errors. This feedback is focused on a student's potential for success, so it remains supportive and encouraging, but the directness assures that a student understands why it's important to make these changes.

Augmenting Written Feedback

Although tutors' written feedback constitutes the majority of an advice letter, we also make a concerted effort to include items other than text in the advice, such as multimedia resources. Our view is that there is no need to confine our feedback to one form or another. In a well-crafted piece of advice, written aspects will complement and reinforce multimedia pieces, and vice versa. The research pointing to the benefits of audio and video feedback is substantial and growing (Cavanaugh and Song; McCarthy; Borup et al.; Silva) as more and more educators take advantage of available technology to distinguish online learning from its distance education roots. Josh McCarthy found a strong preference among students for video feedback compared to audio-only or written feedback (160-161). Students surveyed noted the personalization and detail of the video feedback. A minority of students preferred written feedback to audio or video, stating that they did so because the written feedback helped them to more easily establish and effect a revision plan.

Our tutors include audio and video elements in their advice for varied reasons and in varied ways. The most immediate is a brief audio or video introduction by the tutor, explaining to students what to expect in their advice, like the ones below:

|

| Figure 2. Audio and visual elements in tutors' advice letters. |

Tutors are taught how to create and embed these audio recordings and videos as part of their initial education. A student then knows from page one that the work submitted was reviewed by another person, that a human being has invested time and energy in the student's success. If they choose, tutors can learn more advanced techniques and integrate other audio or video feedback for students. The simple awareness that she is not alone in this endeavor can be significant for students whose "classroom" might be a laptop and a quiet (or not so quiet) space.

In addition, tutors embed EWC-created tutorials complementing the application of certain concepts to students' own work. Rather than only reading a block of text detailing the construction of a literature review, for example, students can consult a handout with graphics or a video lesson on the topic designed to engage them in multiple ways and reinforce learning. These might be resources created by or with tutors, such as the materials used in our in-class workshop program2 or through our monthly series of general-topic YouTube broadcasts. These learning resources enhance and accentuate the focus on the student's own writing, which we believe is central for successful feedback.

Figure 3. Monthly YouTube workshops.

Synchronous Online Options

As mentioned previously, asynchronous tutoring is a good fit for UMUC because our students—working adults located around the world with a multitude of nonschool responsibilities—require a service that is more flexible in terms of their time and accessible regardless of changing situations in their lives. Rather than setting aside a block of time in which to work with a tutor, they can receive their advice and apply it on their own timetables. As with most things, though, "one size fits all" is not the most effective approach, so we offer the option of 60-minute synchronous sessions as well. Many platforms exist for conducting synchronous tutoring sessions, from the very specialized, like WCOnline, to the generic appropriated for the purpose, like Google Hangouts or Skype. Our writing center uses the WebEx platform, where students and tutors can use video, audio, phone, or text chat. We use WebEx for two primary reasons: first, our school has an institutional license for this product; second, WebEx, like several other products, allows for recording of the session. Within 24 hours of the session, students receive a concise written summary of it, as well as a recording. Just as in our asynchronous tutoring, both students and tutors can refer to these summaries for future reference to the lessons learned in the session. Beyond that capability, our concerns were with screen-sharing and note-taking options within the virtual interface. Educating tutors about the technical aspects of tutoring online, both synchronously and asynchronously, is a vital part of the process. Furthermore, ensuring that tutors are confident to educate students about those technical aspects—in the case of confusion or problems—is required for efficient delivery of service.

From a tutor education perspective, the development plan for working synchronously piggybacks on the initial education tutors receive. That is, all tutors begin working asynchronously, and after gaining experience—usually at least two semesters' worth—they can choose to engage in an additional education program to add synchronous availability to their schedules. We regard our synchronous tutoring program as a variation in setting, but not rationale, and grounding tutors in the organizational aspects of creating asynchronous advice helps with time management and focus in synchronous sessions. In addition to mastering technical skills (using the WebEx platform), synchronous tutor education focuses on learning how to adapt our methodology to a real-time session. Like asynchronous tutor education, synchronous education is conducted online through a series of self-paced activities. These begin with the history, rationale, and basic operations of the EWC's synchronous program. Tutors then complete several WebEx training modules, read and respond to articles on the topic, and finish by practicing synchronous sessions with the tutor education coordinator. Because the coordinator is already familiar with each tutor's previous work in the asynchronous program, it's common for discussions to refer to specific characteristics of their tutoring practice and style and how these can transfer to a live setting.

Many tutors join the EWC with face-to-face writing center experience, which shares some skill sets with synchronous online tutoring (interaction, time management), but can differ in meaningful ways, such as the mediation of the technology and consciousness of the recorded product. Because of the nature of our program—tutors working asynchronously before joining the synchronous service—we also have tutors who are tutoring one-on-one in real time for the first time. Even those who bring experience from a face-to-face center have generally grown accustomed to being able to research, revise, and rework an asynchronous advice letter, so the unpredictability of synchronous tutoring can require some acclimation (or reacclimation). In both asynchronous and synchronous tutoring, we emphasize prioritizing advice, beginning with global concerns and gradually working down to local ones. It is common for students, especially those with deadlines on the same day as a tutorial, to indicate that they are "only" interested in citation or grammar advice. We ask tutors to still offer higher-order advice if it is needed, but to remain flexible as well. For instance, a tutor might say to a student, "I'll be happy to discuss MLA style/commas/run-ons with you, but first, I would like to talk a little about your thesis/organization/introduction." If a writer persists and indicates that she's only seeking advice on one issue, then tutors may focus on that, but indicate that if she decides later that she'd like feedback on other issues, advisors are available.

An unexpected but welcome result of our synchronous tutoring has been the development of ongoing writer and tutor working relationships. Because all synchronous tutors start out in the asynchronous program and then have an option to join the synchronous program, they tend to be eager for the type of continued collaboration our synchronous program offers. Sarah Rilling points out that "The ideal for tutoring writing is to work with a student over a period of time and through several assignments, with the goal that writing can truly show improvement, but often writing center tutors must adapt to provide feedback to students in what might be a one-time exchange" (367). Even though our asynchronous advising program has many regular users (see note 1), writers generally work with a variety of tutors during their academic career. If a writer requests a particular tutor, our coordinators make every effort to assure this, but individual part-time tutors on our staff are not available each and every time, so the session is typically assigned to a tutor working at that time so as to provide more prompt service. The benefit is that writers get multiple perspectives from a variety of readers; the downside is that writers and tutors are often unable to continue a conversation. Writers who use the synchronous service, though, schedule their own sessions in a Google Appointment Slots calendar, so they are able to see when their preferred tutors are available and plan accordingly. While it remains a fraction of our asynchronous service in terms of volume, students who use our synchronous service tend to be enthusiastic about it, frequently becoming repeat users. During the 2016-17 academic year, 88% (906 out of 1031) of our synchronous sessions were conducted with writers who used this service multiple times.

Assessment

Our raw usage numbers provide useful information regarding identification of top users among UMUC's degree programs and getting a handle on overall traffic—but our data falls woefully short in answering many of the questions we both have as researchers and are asked by our colleagues in other departments. As is the case with many writing centers, assessment of our tutorials' effectiveness on student learning is a complex task. While correlation between effective tutoring and class performance might be borne out by some preliminary data, that relationship is complicated by the self-selective nature of writing center use: many students who elect to use a service like tutoring are typically highly motivated already and tend to be accomplished learners, which can skew any measured progress correlated with tutoring use. We are, as of this writing, taking steps to better integrate writing center services with the rest of the student experience, allowing us to capture more significant data about how a tutoring interaction affects the broader learning path. As we understand learning progress better across the student experience, we can better refine the tutor education process to ensure our work is complementing that progress.

We are able to assess the effectiveness of our tutor education program with more confidence. Because we set clear expectations for tutors in terms of the personalization of the advice they produce, the integration of supporting resources, the formatting of the advice document, the management of their time, and other factors, we have solid benchmarks against which to measure tutor performance. We review tutor performance annually based on a rubric of our own design. By evaluating a representative sample of the tutor's work, we can assess where one might have "drifted" from the expectations presented in the initial education experience. Such departures are not unusual, nor are they particularly alarming. As a tutor becomes more comfortable in the work environment, certain aspects of practice will be refined: tutors build confidence in themselves, discover new techniques, and become more familiar with our curricula and student needs. Other aspects of their work might deteriorate slightly as tutors are further removed from the direct instruction of their initial education experience and—rightfully—explore the realities of tutoring "on the ground" with live students in varied circumstances. We compare this to how a student learning to write in new contexts and with new expectations might simultaneously gain new skills while also experiencing a setback in previously established skills, as described in Nancy Sommers' research (2006).

We take these initial and then annual reviews as opportunities to have meaningful discussions with tutors, a sharing of perspectives on what tutoring is and what we would like it to be. Much like a tutoring session itself, we want to recognize where tutors are excelling while noting areas for improvement—and, vitally, providing the means to achieve that improvement. This might involve referring them to additional reading or other resources or creating an ongoing education plan with further assessment and discussion. Even tutors with years of experience can benefit from review of and feedback on their work, especially as available technology changes our capabilities and expectations of student writing ability are further refined at the institutional level. In essence, tutor education in some form continues for the duration of the tutor's association with our writing center.

Conclusion

As an entirely virtual writing center, the Effective Writing Center at the University of Maryland University College's circumstances are atypical, but as distance learning increases in popularity, our circumstances are likely to become more common. We believe that a tutor education program designed to help new tutors capitalize on the advantages of an online writing center, including practicing and modeling effective academic writing, connecting past tutorials to current ones, and tutoring within the confines of written work is key to effective tutor education in a virtual writing center. Moreover, some aspects of a successful educational experience—support, presence, time management—are especially challenged in an entirely online environment, so programs can focus on strategies for integrating these into tutors' own work. It is also important to recognize that distance learning technology and the tools students use to learn online are constantly evolving, so tutor education programs need to evolve as well. For example, the EWC has educated tutors asynchronously and online ever since it was founded, but as the university has improved its use of technology and has integrated new learning platforms, our center has as well, in order to ensure our tutor education process reflects tutor-student interaction and prepares tutors to work with members of the UMUC community. We will continue to develop alternatives to traditional interactions, means, and spaces so our tutors can work effectively and our students can learn to the best of our ability, while utilizing the benefits of an online workspace.

NOTES

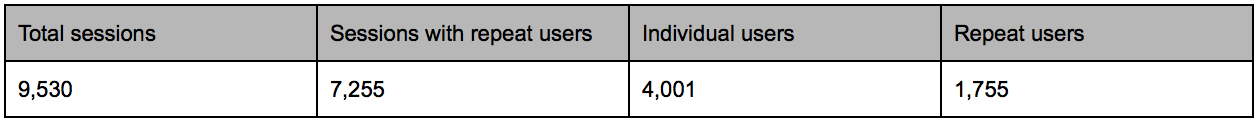

1 (back to text) All tutors in the Effective Writing Center—approximately 40 of them at any given time—work remotely from various locations around the world. The vast majority are part-time employees whose weekly hours can vary widely depending upon student demand and personal preference, but cannot exceed 19 hours per week, per state regulations. Tutors bill the time they work, with an expectation of an hour and a half per session average. We understand that some sessions—particularly with writers who are new to the writing center and/or writing more complex upper-level undergraduate or graduate projects—will require more time. Others, such as brainstorming sessions, might require less. Our administrative team reviews the amount of work completed compared to the hours reported on a term basis and intervenes when there is an egregious disparity. Such an intervention might result in additional development opportunities to help tutors make the most of their time or simply a better understanding of that tutor's workload, which could justify a higher-than-average amount of time per session.

AY 2016-2017

2 (back to text) The in-class workshop program is something of a hybrid between a workshop program and a writing fellows program (and, indeed, the tutors who work in this program are called Writing Fellows). All writing fellows were tutors prior to becoming fellows (and still work in the one-on-one service as well), who then undergo additional education to deliver workshops. The workshops are requested by faculty (or, in some cases, by program chairs for all sections of a particular class). For a period of 1-2 weeks, in the lead-up to a writing assignment, the Fellow is embedded in the online classroom to deliver relevant instruction and materials and help students develop the positive habits (identifying a writing process, conducting research, outlining, brainstorming, drafting, revising, etc.) that lead to writing success.

Works Cited

Angelov, Dimitar, and Lisa Ganobcsik-Williams. "Singular Asynchronous Writing Tutorials: A Pedagogy of Text-Bound Dialogue." Learning and Teaching Writing

Online. Eds. Mary Deane and Teresa Guasch. Leyden: Brill, 2015. pp. 47-64.

Borup, Jered, et al. "Examining the Impact of Video Feedback on Instructor Social

Presence in Blended Courses." International Review of Research in Open and

Distance Learning, vol. 15, no. 3, 2014, pp. 232-56. eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1033092.

Breuch, Lee-Ann M. Kastman, and Sam Racine. "Developing Sound Tutor Training for Online

Writing Centers: Creating Productive Peer Reviewers." Computers and Composition, vol. 17, no. 3, 2000, 245-63.

Cavanaugh, Andrew, and Lyan Song. "Audio Feedback Versus Written Feedback: Instructors' and Students' Perspectives." Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, vol. 10, no. 1, 2014, pp. 122-38.

Gladstein, Jill, and Brandon Fralix. National Census of Writing. https://writingcensus.swarthmore.edu.

Harris, Muriel. "Using Computers to Expand the Role of Writing Centers." Electronic Communication Across the Curriculum, edited by Donna Reiss, Dickie Selfe, & Art Young. National Council of Teachers of English, 2008. 3-16.

Hewett, Beth L. The Online Writing Conference: A Guide for Teachers and Tutors. Boynton Cook , 2015.

McCarthy, Josh. "Evaluating Written, Audio and Video Feedback in Higher Education

Summative Assessment Tasks." Issues in Educational Research, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 153-69.

Rafoth, Ben. "Responding Online." ESL Writers: A Guide for Writing Center Tutors, 2nd ed., edited by Shanti Bruce and Ben Rafoth. Boynton/Cook, 2009. pp. 149-160.

---. "Why Visit Your Campus Writing Center?" Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Vol. 1, edited by Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky. Parlor Press, 2010. pp. 146-155.

Rilling, Sarah. "The Development of an ESL OWL, or Learning How to Tutor Writing Online." Computers and Composition, vol. 22, no. 3, 2005, pp. 357-74.

Silva, Mary Lourdes. "Camtasia in the Classroom: Student Attitudes and Preferences for Video Commentary or Microsoft Word Comments During the Revision Process." Computers and Composition, vol. 29, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1-22.

Sommers, Nancy. (2006). "Across the Drafts." College Composition and Communication, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 248-57.

"The Distance Education Enrollment Report 2017." Online Learning Consortium, https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/read/digital-learning-compass-distance-education-enrollment-report-2017. Accessed 24 June 2018.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank David Taylor, Anna Dumonchelle, Michelle Bowman, Monique Bishop, and the rest of our excellent team at the Effective Writing Center.

BIO

Aimee Maxfield is the lead advisor for training at the University of Maryland University College Effective Writing Center. She worked as an online writing advisor and writing fellow from 2005 to 2010. She has a Bachelor of Arts from the University of North Carolina–Greensboro, and master's degrees from the Shakespeare Institute at Stratford-upon-Avon and the University of Maryland, College Park. In addition to her work at the EWC, Aimee has taught courses in academic writing, drama, and Shakespeare. Her research interests include depictions of community in Medieval mystery dramas and contemporary American passion plays, as well as early modern textual history, bibliography, and performance studies.

Dan Gallagher is the Director of the Effective Writing Center at the University of Maryland University College and has been since 2010. He has a master's degree in creative writing from Temple University, where he worked as a tutor and administrator in the Writing Center. At UMUC, Dan has also directed the Introduction to Research course, taught the Prior Learning course, and served on a number committees focused on academic integrity, information literacy, critical thinking, and written communication.