CHAPTER ONE

First Things First: An Introduction to

Administration at a New Directors' Retreat

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Holly Ryan

Penn State Berks

"Here's how the game is played," I tell a group of eight new writing center directors. "It's like the sleepover game 'Never Have I Ever,' but instead of saying something you've never done before, you say what you never thought you'd have to do as a writing center director. Here's an example: 'Never did I ever think that I would have to ask my dean for a budget for the writing center.' Then, you explain that situation, and others in the group can weigh in on their own experiences around that situation. Make sense?"

I looked around at eight smiling faces, eager to share their most fantastical stories from their first year(s) as a writing center director. The never-have-I-evers ranged from relatively familiar experiences (being over-extended, and working outside of one's expertise) to the truly bizarre (comforting a crying dean, and explaining to a tutor why having different handouts for women and men is a bad idea). This icebreaker activity, played at the beginning of a two-day new directors' professional development retreat sponsored by the Mid-Atlantic Writing Centers Association (MAWCA), has multiple purposes: 1) it serves as an introduction to the retreat participants; 2) it sets a tone of honesty, playfulness, and comradery for the two days; and most importantly, 3) it reminds directors they are not alone even if their situations are idiosyncratic.

| Figure 1. Karen-Elizabeth Moroski shares why she values the retreat. |

As the participants shared their stories that morning and throughout the retreat, it became increasingly clear that many of the directors had little to no peer support on their campuses, and the retreat, more than any other professional development opportunity, provided them a community of professionals to share their successes, failures, and questions. Participants at the MAWCA retreat often report that they run their writing centers and develop their staff education opportunities in isolation. At Penn State University Park campus, Dr. Karen-Elizabeth Moroski is one of two writing center people. In this video (Figure 1), she describes her lack of networking opportunities on her campus and relays why she values the retreat.

This retreat, in particular, emphasizes networking and professional development education for the initial needs of directors. Alternative names for the retreat might be "You've Been Hired: Now What?" or "First Things First: The Administrative Life of a New Director." In the rest of this chapter, I discuss the organizational structure of the retreat, the value of the space and place, and the kinds of questions and insights new directors have shared with me. I provide a general overview of the retreat, describe the focus and materials for the four modules used to organize it, and reflect on what might be helpful for new directors as they start their careers as writing center professionals. This retreat helps new directors attend to administrative issues that need to be addressed before they can develop effective tutor education programs.

This retreat, in particular, emphasizes networking and professional development education for the initial needs of directors. Alternative names for the retreat might be "You've Been Hired: Now What?" or "First Things First: The Administrative Life of a New Director." In the rest of this chapter, I discuss the organizational structure of the retreat, the value of the space and place, and the kinds of questions and insights new directors have shared with me. I provide a general overview of the retreat, describe the focus and materials for the four modules used to organize it, and reflect on what might be helpful for new directors as they start their careers as writing center professionals. This retreat helps new directors attend to administrative issues that need to be addressed before they can develop effective tutor education programs.

Design of the Retreat

From the site location to the initial call for applications, the retreat is focused on appealing to local directors who want to develop a local network of professionals while also having the space and time to develop best practices for their institutional context. The New Directors' Retreat, similar to the IWCA Summer Institute but on a much smaller, regional scale, has the following call for applications:

This two-day event is an opportunity for new/newer writing center directors [1-3 years in the position] or graduate students in administrative roles to focus on the nuts and bolts of writing center administration while networking with other local writing center professionals. This retreat will provide space and time for participants to gather, discuss, support, brainstorm, collaborate, and engage with other individuals who are similarly positioned.

Retreat topics will focus on concerns or challenges we face when running a writing center. There will also be open times for participants to bring forward individual concerns for the group to help troubleshoot. In addition to whole group discussion and activities, participants will also have individual time to work on developing their own personalized approaches to the topics. [Cost is $150 for registration, lodging, and meals.] (mawca.org)

There are a few important things to note in this call. First, the event is for only two days (unlike the IWCA retreat which is a full week), in order to attract writing center professionals who have staff positions. Whereas faculty often do not teach in the summer, staff are often on 12-month contracts; they are able to take one or two days out of the office, but much more than that is challenging. Therefore, we hold the event on one weekend day and one week day. We do not use the entire weekend because that is equally (if not more!) difficult for our participants who have families to care for. Another important note is the cost of this retreat. It is only $150 for food, lodging, and meals. This is significant because many participants report that they run their centers on shoestring budgets, and they sometimes have to pay for this retreat out of their own pockets. Keeping the cost low is essential for being as inclusive as possible. Finally, the location is attractive because people can often drive to the Philadelphia location, and the people they meet at the retreat are people they will likely see again at the regional conference. Developing these local networks can help isolated directors feel more part of a community.

| Figure 2. Tim Smith explains the information he sought from the retreat. |

As part of the application process, participants explain why they are interested in the retreat. Directors often respond with answers that include a desire to network, but they also seek ideas to implement in their own centers. In this video (Figure 2), Tim Smith, the writing center director at Harrisburg Area Community College, articulates his reasons for attending the retreat. He explains that he was seeking information on best practices from the literature but, more importantly, from his colleagues who had tested ideas in their centers.

Tim's response is aligned with others who have attended national retreats. Anne Geller and Michele Eodice found that after people participated in IWCA's Summer Institute, they felt "connected to their colleagues and peers and to disciplinary conversations" (6) which are hallmark outcomes of positive networking experiences. Beyond networking, though, this retreat becomes an educational space, turning new directors toward colleagues and best practices that can help them design their staff education. Since many of MAWCA's participants are unfamiliar with WCenter and have no one that does the same work as them at their home institutions to brainstorm ideas with, the retreat becomes their first real socio-educational opportunity in their new positions.

|

| Figure 3. The retreat site at Pendle Hill. Image downloaded from the Pendle Hill website. |

Finally, in an effort to create a community-oriented space, we chose a location that contributes to this goal. The retreat takes place at Pendle Hill, a Quaker retreat center outside of Philadelphia. It is a quiet, rustic location that offers quaint meeting spaces and lodging facilities, nature trails, an art studio, a library, fresh food made from local ingredients, and a peacefulness that invites reflection and contemplation. With modest yet sufficient accommodations, retreat participants are able to focus on the tasks at hand while feeling like they are in their grandparents' living room. Furthermore, since the staff cook nourishing food, do housekeeping, and provide homemade snacks, participants feel cared for and even a bit pampered by the experience.

The casual hominess along with the lack of distraction contribute to the retreat's overall mood. Janel Dia discusses the value of a place like Pendle Hill in her video (Figure 4) describing what she appreciated about the retreat:

| Figure 4. Janel Dia reflects on the value of the retreat location. |

First Things First: The Modules

Developing the retreat in some ways parallels designing staff education opportunities. I had to decide what to include, how to balance depth and breath, and how to provide formal educational opportunities (readings and "lecture") with collaborative and individual learning moments. The Resources page on the IWCA website, which provides among other things a bibliography to excellent resources such as The Writing Center Resource Manual, was a good start, but I also reflected on my own experiences, remembering what I needed when I began as a new director. Additionally, I looked back over WCenter, seeing patterns in what people were asking that might be helpful for developing the retreat. I ultimately settled on the four modules described below because they seemed like the areas that most new directors are asked to deal with when they begin their positions, and the topics touch on issues that continue to be part of their everyday work, even long after the "new" is removed from their titles. Nikki Caswell, Jackie Grutsch McKinney, and Rebecca Jackson report finding that most directors have (among other things) the task of educating tutors, marketing the writing center, and creating and executing assessment plans (173). I have modules in each of these areas and added a module on creating foundational documents since I had to spend my first year as a director developing those materials.

|

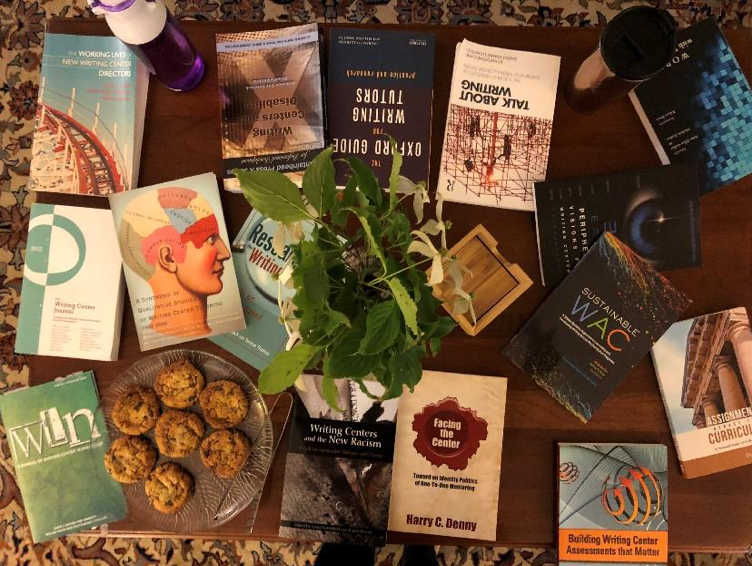

| Figure 5. A coffee table view of resources and cookies provided by Ryan. |

The retreat is broken in four modules (see Appendix B for the itinerary). The topics of the first two modules lay the foundation for the final two. We start with Foundational Documents and Branding. The next day we use what we discussed on day one to discuss Staff Education and Assessment. In each module, participants are given a reading, a short introduction to the topic, and example texts. After guided discussion of the materials (see the individual module sections and Appendix A for a list of resources provided to attendees), participants share what they have done at their center as it relates to the topic and bring up issues/questions they have. They are then given an hour to work independently on crafting or revising their own center's materials. At the end of the day, we have a workshop where people receive feedback from other participants and me. We intermingle all of this with food and socializing in hope of fostering a positive, open environment.

First Module: Foundational Documents

The retreat begins with a focus on foundational documents, mission statements and strategic plans, which are not the sexiest documents, but they articulate the vision and goals of the writing center. Frankie Condon says it best when she writes, "Mission statements name commitments to quality and service and as such serve as a means by which an institution or institutional site can hold itself accountable or be held accountable to the constituencies it seeks to serve" (23). Strategic plans have a similar function: they articulate the values of the institution while also delineating the moves that need to be made to achieve the writing center's goals. As far as

I am concerned, in an ideal world, creating these documents should be the first task of a new director. I understand it does not usually happen that way since tutor hiring, staff education, and scheduling usually are priorities. However, whenever possible, these documents need to be a top priority for directors because a mission and strategic plan dictate the goals and aspirations of the center. Without a clear vision of what the center is and where it's going, a director can get trapped into commitments that do not support the goals of the center. Participants seem to agree. Stacey Hoffer (Figure 6) discusses the value of thinking through and creating foundational documents at the retreat:

| Figure 6. Stacy Hoffer details the value of foundational documents. |

When I introduce mission statements and strategic plans at the retreat, I find that most new directors are in one of the following situations: 1) they have neither; 2) they have a mission statement created by someone else, and they do not have a strategic plan. No one has yet been in the scenario where they have personally created both documents. For those who do have a mission statement, they often admit to not really knowing what it says or only looking at it for their job interview. Since it was created by someone else, they have not used it as a guiding philosophy for the center.

Given that this is new territory for most retreat participants, we invest time reviewing sample documents; however, most of the time is focused on goal-setting activities. Some of these activities might include a SWOT analysis1 (see Matthew Ortoleva and Jeremiah Dyehouse's article "SWOT Analysis: An Instrument for Writing Center Strategic Planning" for ways a SWOT analysis can inform a strategic plan) or a mini-lexicography2 analysis that Eliot Rendleman describes in his article "Lexicography: Self Analysis and Defining the Keywords of Missions."

Given that this is new territory for most retreat participants, we invest time reviewing sample documents; however, most of the time is focused on goal-setting activities. Some of these activities might include a SWOT analysis1 (see Matthew Ortoleva and Jeremiah Dyehouse's article "SWOT Analysis: An Instrument for Writing Center Strategic Planning" for ways a SWOT analysis can inform a strategic plan) or a mini-lexicography2 analysis that Eliot Rendleman describes in his article "Lexicography: Self Analysis and Defining the Keywords of Missions."

During this brainstorming stage, many new directors lament how much they are tasked to accomplish in their centers. They are often asked to serve on multiple committees, work on retention initiatives, partner with other programs to create new programming, all while maintaining tutoring and management roles. Furthermore, some of them have responsibilities far outside their expertise. One director shared that he has been put in charge of the office of disability services, despite having no experience with the laws regarding people with disabilities in higher education. The directors recognize that their centers are often doing good work, but they feel overwhelmed (and excited) by the expectations, some of which were put upon them because "the previous director did it." To complicate matters, all participants in these retreats have been staff members (not tenured faculty) who strongly feel the hierarchical power structures weighing on their decisions. Often new to the university, or at least new to a management position, the directors I work with have felt obliged to agree to the demands of their supervisors.

For these reasons, I tell them that the mission statement and strategic plan can be a lifeline for them—especially in the first few years of the position. I encourage them to draft their plans at the retreat, bring them back to their centers and revise them with their staffs, and then bring the documents to their supervisors for feedback. Once those three constituencies have agreed with the goals and vision of the center, then directors can use that to remove themselves from committees, align themselves with appropriate programs, and feel empowered to refuse when the request does not fit into the plan. Of course, I do not want to imply that mission statements and strategic plans are the salve for these labor inequities. These dynamics are much more complicated than what two pieces of paper can solve. However, these documents do have some weight in multidimensional organizations like institutions of higher education, and they can have rhetorical value to various constituencies.

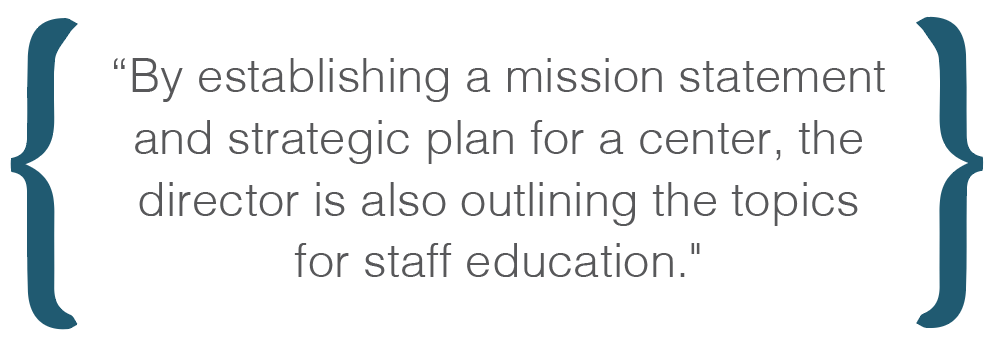

Finally, these documents can have a significant impact on tutor education. For example, if a mission statement indicates that a center is a collaborative space, then directors have to find ways to teach their tutors about the tenets and practices of collaboration. If a mission statement indicates that the center works with all writers at any stage of the writing process, then a director needs to educate tutors about various kinds of writers, the writing processes, strategies and theories about writing processes, etc. If a mission statement or strategic goal is to work with writers in multiple modalities, then directors should be exploring how to use technologies in sessions. By establishing a mission statement and strategic plan for a center, the director is also outlining the topics for staff education.

Finally, these documents can have a significant impact on tutor education. For example, if a mission statement indicates that a center is a collaborative space, then directors have to find ways to teach their tutors about the tenets and practices of collaboration. If a mission statement indicates that the center works with all writers at any stage of the writing process, then a director needs to educate tutors about various kinds of writers, the writing processes, strategies and theories about writing processes, etc. If a mission statement or strategic goal is to work with writers in multiple modalities, then directors should be exploring how to use technologies in sessions. By establishing a mission statement and strategic plan for a center, the director is also outlining the topics for staff education.

Second Module: Promotion and Branding

Once participants have worked on articulating their goals for the writing center, then we discuss promotion and branding. This module needs to be tackled after we have discussed the mission statement and goals because marketing is contingent on how the center is identified. This section of the retreat is when we start to discuss how various promotional materials and activities need to be rhetorically savvy.

To begin this module, I share two articles with the participants. The first is Muriel Harris's "Making Our Institutional Discourse Sticky: Suggestions for Effective Rhetoric," and the second is an article I published with and Danielle Kane titled "Evaluating the Effectiveness of Writing Center Classroom Visits: An Evidence-Based Approach." Participants are not expected to read them before we meet. Instead, I talk through the key points of each article, primarily focusing on the good advice that Harris offers in her piece. I outline some of the ways we promote the writing center (classroom visits, flyers, pens, syllabus statements sent to faculty, email, department meeting reports, annual reports, and those fun little bouncy balls that some centers buy, among other things) and invite participants to share their own cool or unique strategies.

Following this orientation to marketing, I have participants identify various audiences at their university who interact with the writing center. From there we create graphic organizers (charts, lists, graphs, pictures, etc.) to figure out what is working and what may need to be revised in light of the two articles we discussed. The directors then work individually to decide how to allocate their time and resources to these different marketing and branding opportunities. Does it make sense to do classroom visits? Would it be best to do one visit during orientation for incoming students? Do they want to increase the number of juniors and seniors who visit in the writing center? If so, what actions might accomplish that? Do they have a problem with faculty buy-in? How they can they shift that perspective?

On its surface, promotion and branding may not seem directly connected to staff education, but there is an important connection between the two. Part of staff education is recruitment. Of course, directors have to think carefully about what kinds of opportunities we provide for our tutors to help them learn, but we also have to find good, competent tutors to teach. A center's campus brand can impact who becomes a tutor, either through self-identification or through faculty referrals. If faculty believe that the writing center is a "fix-it" shop, then they might only recommend students with excellent sentence-level proficiency. If a writing center has a reputation of an inclusive, diverse, dynamic environment, then some students might self-select to apply to work at that center. There are many scenarios that could be true here. Regardless of the particulars, a writing center's brand can have an impact on who becomes a tutor, which impacts staff education.

On its surface, promotion and branding may not seem directly connected to staff education, but there is an important connection between the two. Part of staff education is recruitment. Of course, directors have to think carefully about what kinds of opportunities we provide for our tutors to help them learn, but we also have to find good, competent tutors to teach. A center's campus brand can impact who becomes a tutor, either through self-identification or through faculty referrals. If faculty believe that the writing center is a "fix-it" shop, then they might only recommend students with excellent sentence-level proficiency. If a writing center has a reputation of an inclusive, diverse, dynamic environment, then some students might self-select to apply to work at that center. There are many scenarios that could be true here. Regardless of the particulars, a writing center's brand can have an impact on who becomes a tutor, which impacts staff education.

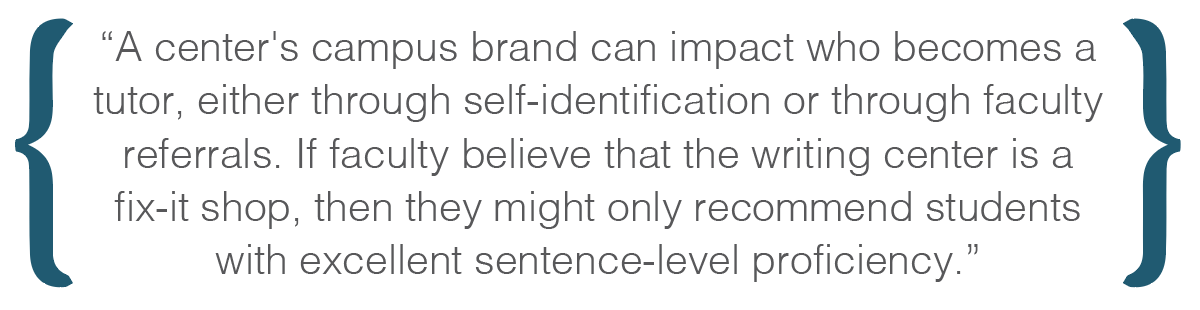

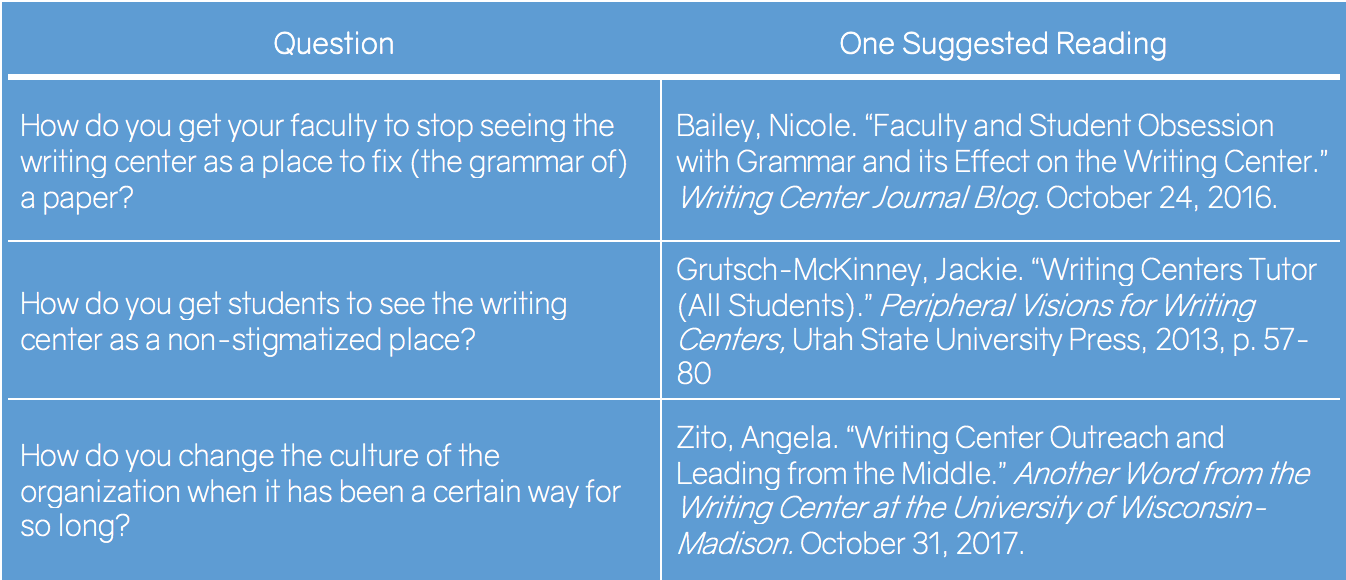

Similar to the previous module, this independent working time often results in shared troubleshooting and mentoring sessions. There seem to be three prevailing questions that new directors ask one another:

Similar to the previous module, this independent working time often results in shared troubleshooting and mentoring sessions. There seem to be three prevailing questions that new directors ask one another:

- How do you get your faculty to stop perceiving the writing center as a place to fix (the grammar of) a paper?

- How do you get students to see the writing center as a non-stigmatized place?

- How do you change the culture of the organization when it has been a certain way for so long?

These are three hard questions that new directors are facing, and I have no easy answers for any of them and neither do the other participants. We discuss the value of time, visibility, leading by example, making hard decisions, leadership qualities, power, emotional energy, and the balance between durability and flexibility. I provide article and book titles when I can (see Figure 7 for a few titles), and shake my head knowingly as they share their own stories. Other retreat participants share their resources and experiences as well in hopes that something they have done can translate to another context.

|

| Figure 7. Prominent questions and suggested readings. |

This is a challenging module, but it is also the one during which people really start to network and connect with each other. While the other modules are intellectually stimulating, this module is often emotionally charged. The three questions asked by participants usually arise from a frustration and feelings of powerlessness to make meaningful change. Oftentimes directors have inherited their job from a predecessor who established the writing center culture on their campus, and the new director is unsure of how to change it. Cultural change happens slowly, and it can be frustrating to have exciting new ideas that are challenged by a community who do not seemingly support those initiatives. I can empathize with new directors because I have felt that way as a director even after having been one for over a decade. This module fosters opportunities for networking and lateral mentoring among the participants. They bond over the shared sense of commitment to the field.

Third Module: Staff Education

The next day, we tackle staff education. Providing an overview for this module is the most challenging since each participant typically has a unique staff makeup and way of providing staff education (if at all). This module also elicits a chatty energy from the group. Overwhelmingly (with a few exceptions, of course), working with their staff is the most enjoyable part of these new directors' jobs. This module has evolved the most over the last four years. When I first started organizing the retreat, I tried to provide an overview and examples for educating staff. However, the session felt underwhelming because I never felt as though we shared enough or that the directors took enough away.

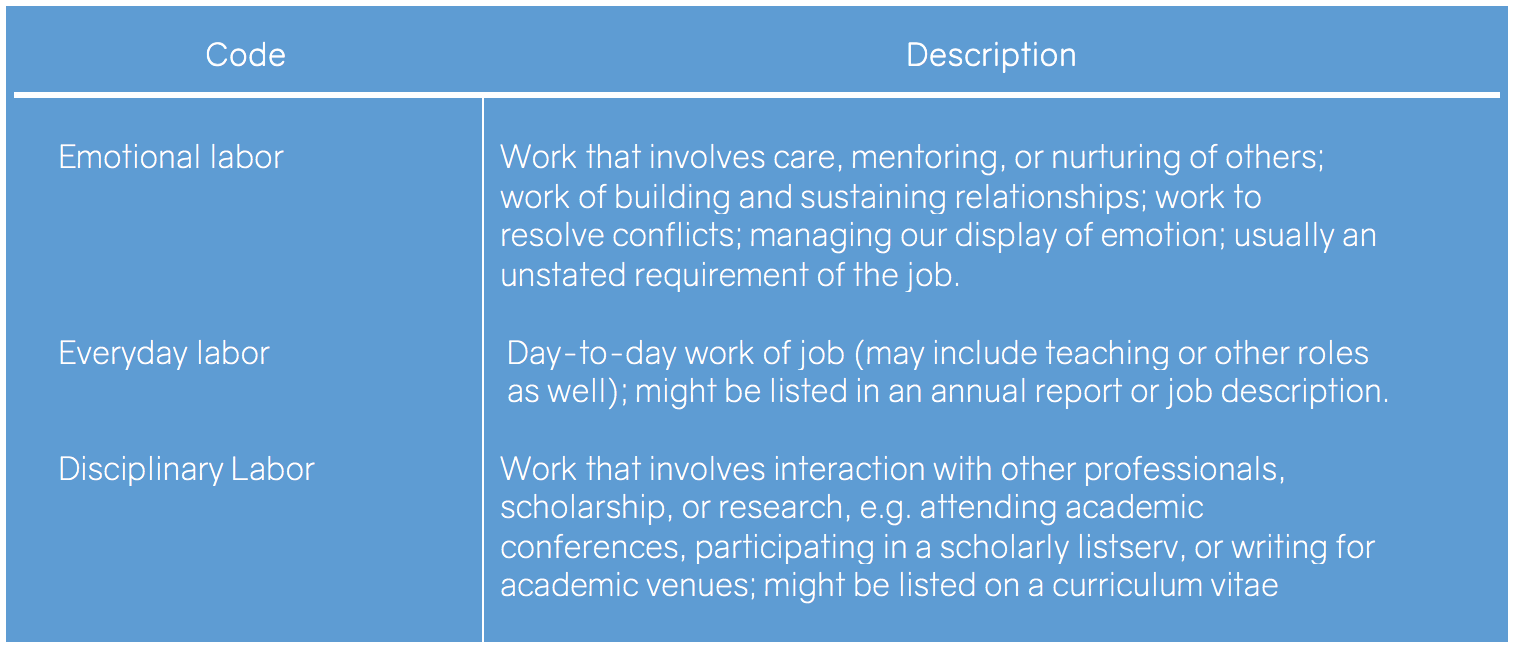

After three years of organizing the retreat alone, I asked Angela Rhoe (Writing Center Director of Montgomery County Community College) to lead the retreat with me. In particular, I wanted her collaboration on the staff education module since I was unhappy with how it had worked in the past. Earlier that spring, Angela had organized a workshop at our regional conference, drawing on the work of Caswell, et al. In our redesign of the retreat module, we decided to return to their book The Working Lives of New Writing Center Directors. In that text, the writers identify three labor categories for directors: everyday tasks (day-to-day, administrative tasks), emotional tasks (building and sustaining relationships), and disciplinary tasks (engaging with/in the academic field) (10).

We posit that many of our undergraduate, graduate, and professional tutors do similar categories of work as directors. While the tasks themselves may not all be exactly the same, tutors are involved in administrative tasks, emotional work, and, through staff education opportunities, disciplinary labor. Staff education, then, should help train our tutors to do that work. Now, in this redesigned module, participants receive Caswell, et al.'s coding scheme chart (see Figure 8). Then, the new directors make a list of work that their tutors do in each category. The directors then identify the ways tutors are trained do those aspects of the job, leaving blank the ones that haven't been attended to in training. (There was a lot unattended to).

|

| Figure 8. Caswell, et al.'s Labor Categories and Descriptions for Writing Center Directors. Adapted from The Working Lives of New Writing Center Directors (27). |

| Figure 9. Tim Smith discusses his new staff education plan. |

Next, the directors write down notes about a lesson, activity, or education exercise they have done with their staff that was popular/successful and connect those to the categories of everyday, emotional, or disciplinary labor. Retreat participants share their activities, promising to email handouts and other materials to others who want to try such an exercise with their staffs. One participant shared that he read his staff members' tarot cards as a community building and interpersonal skills exercise. I left with a page filled with ideas and a realization that I had a lot of gaps to fill in my own tutoring course. Tim Smith left the retreat with a specific plan for adding mentoring to his staff education plan. He explains (Figure 9) in his own words (he begins discussing staff education at 1:50 but the first two minutes are good context for his experience).

During this module, directors ask questions about what the literature suggested were the most successful ways of educating staff and an ideal staff makeup (peer tutor, professional, graduate student). I point them to some of texts such as Lauren Fitzgerald and Melissa Ianetta's book The Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors: Practice and Research. I will now be able to also point them to Julia Bleakney's chapter in this collection to help them think through sequencing and duplicating efforts in their staff education pursuits. The number of those questions were far fewer than in years past, and this time the directors were buzzing with new ideas, excited by the ways they could rearrange and change their staff development. This reminded me of what I felt like when I was a new teacher. I knew the concepts I wanted to teach but did not have any specific strategy for making them happen. I wanted concrete lessons I could implement the next day; I needed "Monday Morning" activities and these directors did too. Not all lesson plans were completely portable (what do I know about tarot card reading!?!), but with creativity, the directors could make connections and import exciting ideas.

During this module, directors ask questions about what the literature suggested were the most successful ways of educating staff and an ideal staff makeup (peer tutor, professional, graduate student). I point them to some of texts such as Lauren Fitzgerald and Melissa Ianetta's book The Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors: Practice and Research. I will now be able to also point them to Julia Bleakney's chapter in this collection to help them think through sequencing and duplicating efforts in their staff education pursuits. The number of those questions were far fewer than in years past, and this time the directors were buzzing with new ideas, excited by the ways they could rearrange and change their staff development. This reminded me of what I felt like when I was a new teacher. I knew the concepts I wanted to teach but did not have any specific strategy for making them happen. I wanted concrete lessons I could implement the next day; I needed "Monday Morning" activities and these directors did too. Not all lesson plans were completely portable (what do I know about tarot card reading!?!), but with creativity, the directors could make connections and import exciting ideas.

My collaboration with Angela and the revisions we made to this unit highlight an important part of director education. Speaking and engaging with other directors is an essential part of what directors need to be successful in their positions. The retreat provides such a space for growth and illustrates that directors can create and refine their programs by "first" carving out time to discuss ideas with fellow directors. In this way, a retreat serves as pre-education for writing center directors before they go on to educate their staff.

In addition to the staff education exercise described above, I also offer some advice for creating their staff education opportunities. This bulleted list is intended to help new directors as they navigate their administrative responsibilities and their staff education curricula.

- Assess the current staff education opportunities for tutors. Do you have a staff education course? Funding for summer education? Funding for regional or national conference travel? Do you have staff meetings that could include education?

- Identify tutors' tasks with respect to the labor categories established by Caswell, et al. Some tutors may not have every role. For example, head tutors might have more administrative tasks than others; graduate tutors may have more disciplinary labor than undergraduate tutors.

- Create lesson(s) for each of these tasks; rely on experts around campus to help educate staff.

- Prioritize the most important aspects of tutors' work and be sure to schedule those at times when everyone can participate.

- Rely on the mission statement and strategic plan to guide staff education goals. For example, if one aspect of the strategic plan is to create more opportunities for biology students to get tutoring, then the director will surely need to do more staff education around writing lab reports, creating visual representations of data, and/or reading scientific journal articles.

- Use physical and online platforms that will help you execute tasks. For example, if part of a tutors' job is reflection, do you want to create an online discussion board for writing? Do you want to have a journal in the center that everyone has to write in 1-2x a month? Do you want each person to speak at one staff meeting a year to share their reflections on a particular topic related to her tutoring?

- Find ways to avoid making extra work for yourself. If you require tutors to blog, for example, to what extent are you required to respond to those? If you encourage tutors to develop presentations for regional or national conferences, you might want to consider setting up peer review groups so you are not the only mentor" .

- Be prepared for hard conversations with your staff and to potentially lose tutors who are not interested in this cultural shift.

This final bullet is hard to write, but it is one of the most important pieces of advice I can offer to center administrators who do not currently offer staff education. Some tutors will welcome the opportunity to learn to improve their tutoring. Others will resist, sometimes strongly. Directors need to develop a strategy for how to handle this resistance. In some cases, it can mean firing a tutor. In others, it means rhetorically listening to try to develop a compromise that meets everyone's needs. Regardless, directors might not want to try to make these sweeping changes without the buy-in and collaboration of their staff. To assess the learning culture in a center, directors might consider using the excellent learning audit checklist (see Appendix C) from The Everyday Writing Center (52). This checklist can help administrators figure out if they work in a pro- or anti- learning culture (52).

Assessment

The final module is typically the most abstract for the new directors. Assessment is a scary word for many of us because so much is tied into the findings (funding, for example), but assessment can be made more palatable when we do not ascribe it so much power. While some new directors have been asked to create an assessment plan, many have not been asked to do more than report the numbers and make up of their writing center sessions, and account for their budgets. Since this is also the last module of an intense two-day workshop, energies have started to wane. I do provide the participants with a chapter from Ellen Schendel and William J. Macauley Jr.'s Building Writing Center Assessments That Matter. I highlight key points from the chapter and then have them return to my article, which is a quantitative analysis of survey data I collected to try to figure out the value of class visits. I use my piece because even though it is a published, research article, it started from a question I had in my writing center: do these class visits actually work? Yes, it's a simple question that led to a significant assessment project, but it did not have to be so involved (if the intent is not publication, then the IRB would not have had to be involved, for example). I provide this article as an example because new directors can ask "Is this working?" to almost anything in their center, including staff education.

In this part of the module, I ask new directors to make a list of questions they have about their center. I encourage them to go back to their mission statements and strategic plans as a way of asking questions. For example, if the writing center purports to help writers develop strategies for writing, a director could ask multiple assessable questions:

- Do we do that?

- Which strategies do we focus on?

- Who is learning these strategies?

- What are the qualities of the writer who is learning these strategies?

- Who isn't learning these strategies?

- What outcomes result from writers learning these strategies?

- How well have tutors been trained to teach strategies?

After they have developed questions, we discuss which ones they would prioritize, for which ones they have already collected data (this often leads into a discussion of WCOnline, a tool that maybe half of the directors have heard about), for which ones they want to collect data, and how they might collect and assess the data. Some directors have big questions that require partnership with their institutional research team or a statistician; others have much smaller questions such as which population(s) of students are apt to use writing center services (which, of course, could be a large question as evidenced by Lori Salem's article "Decisions...Decisions: Who Chooses to Use the Writing Center?"). Regardless of the scope of the questions, directors do leave the retreat with the idea that we need to test our assumptions and theories in the center. They know that data collection is important, but the degree to which they use it will likely depend on a couple factors. Assessment does take time and resources, and even if an individual values assessment, it is helpful if the institution does too. If the university does not ask for much assessment, then new directors should feel comfortable assessing only one or two aspects of their mission statement or goals. As a field, we value reflection and analysis of our work, which is why I introduce it at the retreat, and according to the exit survey, sixty percent of the participants said they anticipate the assessment documents will be the most useful to them one year from when they attend the retreat. My hope is that new directors see the value in assessment also and find ways to test their own theories in their centers.

Concluding Throughts

The MAWCA New Directors Retreat has received positive feedback from its participants. One person wrote, "This retreat was informative and cathartic. I need more of this in my life!" More rewarding to me, however, is that participants continue to use the materials even after the retreat is long over. Stacey and Tim both discuss in their clips that they come back to ideas from the retreat months later. Also, as a testament to the value of the retreat, two participants have come back in subsequent years, anticipating getting something new out of the retreat because they are now ready to think through those concepts. Retreats like this one have value in addressing the immediate needs of new directors and planting seeds that can later be nourished. For example, one new director spent a lot of the free-time developing foundational documents. After a year in the job, she was ready to come back to think more carefully about assessment.

Unfortunately, retreats like this one and the IWCA Summer Institute have not been terribly successful at continuing conversations beyond the retreat. There have been Facebook pages and email listservs developed, but they are spottily used. Caswell, et al. make a similar point. They suggest that the "leaders in the field [should] imagine other sustained ways to help new directors, ways that offer pragmatic and more complex theoretical and political models of writing center leadership" (199). In their chapter in this collection, Russell Carpenter, Scott Whiddon, and Courtnie Morin discuss one way (certification) that leaders in the field could find sustained ways to help new directors. MAWCA has discussed doing a series of workshops that could support mid-career directors. Perhaps these are ways of providing sustained mentorship and "cathartic" engagement to people beyond their first couple years of directing.

Writing center directors are thirsty for educational and professional development opportunities. Similar to ongoing staff education in our centers, directors also need to connect with others in order to grow as leaders. A first step is to carve out time to collaborate and discuss the administrative and teaching responsibilities of a director. Unfortunately, not every region offers a retreat like this, but new directors can try to recreate these experiences by organizing (or joining) regional collaborative get-togethers such as reading groups, themed breakfast conversations, tutor/director meet-ups, or similar networking opportunities. This retreat creates a playful, engaging venue to foster space for growth, and other directors can also create these opportunities, by first committing time to gather with our peers.

NOTES

1 (back to text)

Ortoleva and Dyehouse use Michael Harrison and Arie Shirom's book Organizational Diagnosis and Assessment: Bridging Theory and Practice to describe SWOT as "an acronym for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Common in business settings, SWOT analysis is a tool for organizational management that may be applied effectively to writing centers. SWOT analysis helps administrators understand stakeholder perceptions about the operational effectiveness of an organization by focusing on four related kinds of perceptions—strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats—and interactions within these categories" (p. 2-3).

2 (back to text) A lexicography is a study of words and creating dictionaries, which is an attempt to write a definition that addresses the word's denotation, connotation, sense or semantic relations, and collocation (Rendleman 2). In Rendleman's article, he examines the word "independent writer" in an attempt to get a better sense of what writing center professionals mean when they use that word in their mission statements.

Works Cited

Bailey, Nicole. "Faculty and Student Obsession with Grammar and its Effect on the Writing Center." Writing Center Journal Blog. October 24, 2016. http://www.writingcenterjournal.org/new-blog//faculty-and-student-obsession-with-grammar-and-its-effect-on-the-writing-center.

Bleakney, Julia. "Ongoing Writing Tutor Education: Models and Practices." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Bleakney.html.

Carpenter, Russell, et al. "Understanding What Certifications Mean for Writing Centers: Analyzing a Pilot Program via a Regional Organization." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Carpenteretal.html.

Caswell, Nicole, et al. The Working Lives of New Writing Center Directors. Utah State University Press, 2016.

Condon, Frankie. "Beyond the Known: Writing Centers and the Work of Anti-Racism," The Writing Center Journal, vol. 27, no. 2, 2007, pp. 19-38.

Fitzgerald, Lauren, and Melissa Ianetta. The Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors: Practice and Research. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Geller, Anne Ellen, and Michele Eodice. "The Rewards of Summer: The IWCA Summer Institute," Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 29, no. 7, 2005, pp. 6-7.

Grutsch-McKinney, Jackie. "Writing Centers Tutor (All Students)." Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers, Utah State University Press, 2013, p. 57-80.

Harris, Muriel. "Making Our Institutional Discourse Sticky: Suggestions for Effective Rhetoric," The Writing Center Journal, vol. 30, no. 10, 2010, pp. 47-71.

"MAWCA Retreats." MAWCA: The Mid-Atlantic Writing Center Association, https://mawca.org/Retreats. Accessed 12 Aug. 2018.

Ortoleva, Matthew, and Jeremiah Dyehouse. "SWOT Analysis: An Instrument for Writing Center Strategic Planning," Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 32, no. 10, 2008, pp. 1-4.

Pendle Hill. www.pendlehill.org/.

Rendleman, Eliot. "Lexicography: Self Analysis and Defining the Keywords of Missions." Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 37, no. 1/2, 2012, pp. 1-5.

"Resources / WC Bibliographies." International Writing Center Association, http://writingcenters.org/resources/bibliography-of-resources/. Accessed 12 Aug. 2018.

Ryan, Holly, and Danielle Kane. "Evaluating the Effectiveness of Writing Center Classroom Visits: An Evidence-Based Approach," The Writing Center Journal, vol. 34, no. 2, 2015, pp. 145-172.

Salem, Lori. "Decisions...Decisions: Who Chooses to Use the Writing Center?" The Writing Center Journal, vol. 27, no. 1/2, 2016, pp. 147-171.

Schendel, Ellen, and William J. Macauley Jr. Building Writing Center Assessments That Matter. Utah State University Press. 2012.

Silk, Bobbie Bayless. The Writing Center Resource Manual. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2003.

"SWOT Analysis." Research Methodology. https://research-methodology.net/theory/strategy/swot-analysis/.

Zito, Angela. "Writing Center Outreach and Leading from the Middle." Another Word from the Writing Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. October 31 2017. https://writing.wisc.edu/blog/writing-center-outreach-leading-from-the-middle/.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Penn State University, Berks for a grant that supported the writing of this project. I would also like to thank MAWCA for the opportunity to organize this retreat. Finally, thank you to all the retreat participants for sharing their work and thoughts about the retreat (and for letting me take all those pictures!)

BIO

Holly Ryan (hlr14@psu.edu) is an Associate Professor of English and Writing Center Coordinator at Penn State University, Berks. She serves as the current president of the Mid-Atlantic Writing Centers Association and hosted the 2017 regional conference. She has published in a range of writing center journals including Writing Center Journal, WLN, and Praxis.