CHAPTER FIVE

Taking the High Road to Transfer:

Soft Skills in the Writing Center

TRANSFER OF LEARNING IN THE WRITING CENTER

Mike Mattison

Wittenberg University

In July, 2017, we hired a new president at Wittenberg University. Just after he began his tenure, I saw him in one of the hallways of the administrative building, and I stopped to introduce myself. When I told him I direct the Writing Center, he brightened. "I know about that," he said. "When I went on my campus tour, a young woman stood up and told me all about it." He went on to say how impressed he was with the student (whom he remembered as a swimmer from Cincinnati), as she stood up from behind the desk, introduced herself, and then proceeded to give a short speech about the Writing Center and its operations. Such an exchange happens dozens of times a week between the writing advisors and tour groups of prospective students and their families, as the advisors are charged with telling those visitors about our work.1

Around the same time that summer, I happened upon an editorial in our local paper, one in which the writer warned that businesses "seem to be suffering from employees who lack basic soft skills, such as interpersonal communications, problem solving, business etiquette and the like" (Sheridan). That editorial referenced an article from Business Communication Quarterly, one listing the top ten soft skills desired by employers: integrity, communication, courtesy, responsibility, social skills, positive attitude, professionalism, flexibility, teamwork, and work ethic (Robles 454). The main argument was that these skills need "further emphasis in the university curricula" so that students have them "before they embark on a business career" (455).

|

| Figure 1. Word cloud using terms associated with "soft skills." |

It's a short jump between these two moments. The qualities some find lacking in the business world (and the university) are just those qualities that the writing advisor displayed in her interaction with our president. We in writing centers are probably not surprised about this, either. Consider Sue Dinitz and Jean Kiedaisch's article, "Tutoring Writing as Career Development," where the authors make an explicit connection between writing centers and future employment. From their survey, Dinitz and Kiedaisch found that tutors "placed the highest value on the interpersonal skills developed through tutoring" (2), even more so than writing skills, mentoring skills, and thinking skills. Tutors, the authors reported, spoke of how they learned to empathize, to listen, to ask good questions, to be sensitive to difference. Some also wrote of how the work in a writing center prepared them for interviews, to "become accustomed to having semi-formal conversations with people I'd never met and being prepared with answers to all of their questions" (4).

These comments and results are similar to what Bradley Hughes, Paula Gillespie, and Harvey Kail discovered, and then published, in "What They Take with Them." The tutors who responded to their survey claimed they had become better writers; they "became adept at problem solving" (26); they became better listeners, with a "new appreciation for and facility with listening to others" (28); and they found an "eerie" connection between "peer tutoring and career relevance" (30). The ability to handle job interviews is mentioned again, as is professional advancement. And we find a mention of transfer in the article: "How many other undergraduate courses and experiences could, fifteen or twenty years later, offer such detailed evidence of learning and such detailed evidence of staying power and transferability?" (38). Presumably all the skills former tutors mentioned, from writing to problem solving to talking with strangers, were developed in writing centers and then transferred over to other areas of their lives, both personal and public.

These comments and results are similar to what Bradley Hughes, Paula Gillespie, and Harvey Kail discovered, and then published, in "What They Take with Them." The tutors who responded to their survey claimed they had become better writers; they "became adept at problem solving" (26); they became better listeners, with a "new appreciation for and facility with listening to others" (28); and they found an "eerie" connection between "peer tutoring and career relevance" (30). The ability to handle job interviews is mentioned again, as is professional advancement. And we find a mention of transfer in the article: "How many other undergraduate courses and experiences could, fifteen or twenty years later, offer such detailed evidence of learning and such detailed evidence of staying power and transferability?" (38). Presumably all the skills former tutors mentioned, from writing to problem solving to talking with strangers, were developed in writing centers and then transferred over to other areas of their lives, both personal and public.

Writing Centers and Transfer

That narrative, of tutors gaining and transferring skills from the writing center, is an excellent story, and it provides an engaging angle on transfer that I have not often encountered. Most of the literature that I have found on transfer for writing centers, and for writing studies, focuses on writing. How do students take writing abilities learned in one context, or on one assignment, and utilize it in another? Or, how do writing tutors help students learn how to do that? It's the hard skills of writing or tutoring that are at issue, not necessarily any of the soft skills of relating to people.

For example, in Bonnie Devet's comprehensive primer on transfer and writing centers, she mentions several types of transfer: content to content, procedure to procedure, lateral, vertical, relational, conditional, strategic, reverse.2 In defining those types of transfer, Devet offers up examples, but those examples do not mention many of the top-ten soft skills from the list above. Some types of transfer do seem closely associated with soft skills. For example, to illustrate procedural to procedural transfer, Devet says that "consultants learn a sequence of repeatable skills, such as greeting a client, sitting beside them, and asking them to fill out paperwork" (123). And, with relational transfer, Devet mentions consultants might respond differently to each distracted student they encounter, looking "for reasons underlying the confusion" (124). Such a search for reasons presumably would involve soft skills: listening, (possibly) empathy, courtesy. However, the majority of Devet's article deals with writing or tutorial knowledge. How do tutors transfer what they learn in one tutorial to another, or how do they transfer what they know about writing to other writing situations�or, more often, how do they share that knowledge about writing with other students so student writers can use it?

Facilitating Transfer

The idea of transferring soft skills seems to me to be something else; I do not believe we have talked much about findings like Dinitz and Kiedaisch's or Hughes, Gillespie, and Kail's in the language of transfer. Dana Driscoll does begin to do so in "Building Connections and Transferring Knowledge: The Benefits of a Peer Tutoring Course Beyond the Writing Center," as the students in her course found connections between the class and their future careers, "including pedagogical techniques for future classrooms, future writing situations, and interpersonal skills" (165, emphasis added). Driscoll and Harcourt also examine transfer from a writing center course and offer wonderful advice about metacognitive reflection (thinking about thinking). Their article, though, focuses mainly on "learning and applying rhetorical knowledge, discourse community knowledge, and theories of learning and demonstrating" (5). The piece does not exclude soft skills, but it also does not explicitly tackle them, either. That's the point: the literature I have found does not necessarily talk much about soft skills themselves, at least in those terms. Some excellent articles come close, like Noreen Lape's "Training Tutors in Emotional Intelligence: Toward a Pedagogy of Empathy," in which she advocates for writing center administrators to "nurture emotional intelligence in tutors through heightened awareness, practice, and reflection" (6). This thoughtful, detailed article on how to go about doing exactly that seems a rarity in our field. Lape herself even mentions that lack. When she asked, "How can I best train tutors in the human art of working with a writer's emotions," she looked to tutor training manuals for answers but discovered that "most manuals concentrate far more on cognitive than affective skills" (2). It is the cognitive, or hard, skills that take up most of our attention.

Consider this advice from Lauren Fitzgerald and Melissa Ianetta, in their The Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors (a book published after Lape's article, but one that continues the focus on cognitive skills):

Interpersonal skills: You probably already know how to interact with others, to help put people at ease if they seem to be feeling unsure (which can happen when people share their writing with strangers, and even people they know), to give them space or time if they need it, to listen. All the qualities that go into making you a friendly, helpful person will be an important skill set for this job. (53)

Here, writing tutors are described not so much as developing soft skills in the writing center and transferring them to future endeavors as already having soft skills that they are bringing into the writing center. In this situation, if the transfer of soft skills is happening, it is from tutors' outside lives before the writing center. The soft skills are already assumed; the student possesses them, and probably used them to get the job in the first place.

The literature on writing center hiring practices has for years encouraged administrators to find the "friendly, helpful" people that Fitzgerald and Ianetta describe, to find people who already display soft skills. Consider how Andrea Muldoon describes her hiring process. She claims that "formal hiring practices generally result in higher quality tutors" and allow her to avoid the candidates who "clearly lacked the interpersonal and 'soft skills' necessary for tutoring" (3). Muldoon's advice is just one piece in a long line of similar statements. When administrators discuss how to hire people for writing centers, they talk of finding certain types: people who "enjoy the collaborative process . . . who are good listeners and communicators" (Gillespie and Kail 325), people who display "patience and true concern for helping basic writers" (Cobb and Elledge 125), people who have "consistently demonstrated their verbal skills" (Puma 2). When administrators (or hiring committees) find those people, they can bring them into the center and give them the procedural knowledge they need to help students with writing. It is assumed, in many ways, that the personal attributes will transfer over to writing center work.

In other words, I don't think the literature talks much about transfer and soft skills in the writing center because, as one of my advisors phrased it, "I kind of think that it's all obvious." That's a perspective I can appreciate. We hire friendly, personable students who supplement their soft skills with training in hard skills and then seamlessly step into the writing center and then professional worlds where they can utilize both sets of skills to become successful. If anything, writing centers and soft skills might present a case of what D. N. Perkins and Gavriel Salomon call "low road" transfer. In such cases, there is the "automatic triggering of well-practiced routines in circumstances where there is considerable perceptual similarity to the original learning context" (25). In other words, not much effort is required. The authors even argue that low road transfer "trades on the extensive overlap at the level of the superficial stimulus" (25, emphasis original). They give examples such as how driving a car prepares you to drive a truck. Not surprisingly, this low road transfer is the, well, boring type of transfer. It's certainly not as exciting as "high road" transfer, which "depends on deliberate mindful abstraction of skill or knowledge from one context for application in another" (Perkins and Salomon 25). Shakespeare's metaphors, claim the authors, would be examples of high road transfer.

What worries me is that a majority of the literature might give the impression that soft skills are "at the level of the superficial stimulus," and that tutors, to repeat Fitzgerald and Ianetta's words, "already know how to interact with others" (53). Administrators might not believe there is a need to talk about social etiquette or work ethic or professionalism because those skills are a given.

Complicating the Picture

Recently, though, Tom Earles and Leigh Ryan, in "Teaching, Learning, and Practicing Professionalism in the Writing Center," put forward a different idea. Though they do not use the idea of transfer in their article, they make a strong case that writing centers and administrators have an "obligation" and "responsibility" to prepare our workers to "function in the workplace after graduation." They cite numerous pieces (like the ones mentioned in the first section of this article) that worry over the lack of preparedness in college graduates. What they realize at the end is this:

The reports and articles we found helped us to more completely identify what constitutes professionalism�or lack of it. They consistently reveal that some college graduates have much to learn about demonstrating appropriate soft skills in the workplace, especially those relating to interpersonal skills, a good work ethic, appropriate use of technology, and being focused and attentive. These reports and articles also indicate that many college graduates are not only aware of their need to learn more about professionalism, but they are also desirous of the opportunity.

The important point for Earles and Ryan is understanding that their tutors "didn't know better" about much of this behavior. Acknowledging that ignorance is a first step for many administrators.

Also, administrators should be cautious about privileging soft skills during the hiring process. For one, such a focus can severely limit our pool. As Wendy Cukier, Jaigris Hodson, and Aisha Omar point out, "[b]ecause of the way in which soft skills are learned, many segments of the population are disadvantaged in access to the coaching, training and role models needed to develop these skills and cultural biases may play a role in the definition and assessment of soft skills." Prioritizing soft skills can keep us from diversifying our writing centers in the way that authors such as Ann Green have called for. For example, socio-economic backgrounds might keep one from gaining certain experiences that allow one to succeed in interviews, as J.D. Vance argued in his memoir, Hillbilly Elegy. And, there is the danger that our reading of soft skills is slanted, as Phillip Moss and Chris Tilly noted nearly two decades ago in "'Soft' Skills and Race: An Investigation of Black Men's Employment Problems."

|

| Figure 2. The letters X, Y, and Z, with the Z made of words representing Generation Z. |

Furthermore, we should be aware that fewer and fewer students coming in to college might have had the same opportunities to develop soft skills as they have had in past generations. As Corey Seemiller and Meghan Grace point out in Generation Z Goes to College, technology use by incoming college students nowadays "does not just provide a different method of communicating . . . it forces a rewriting of etiquette rules" (57). There are new expectations of what is "normal" communication. Face-to-face interactions happen less frequently because much communication is done through technology, and Seemiller and Grace state that today's students do not have "much opportunity to hone their skill set to communicate effectively in person; the result is that they lack strong interpersonal skills" (61). In addition, according to a 2015 report from the Pew Research Center, there is a decline in the number of jobs available for teens: "Only about a third of teens (34.6%) had a job last summer, despite some recovery since the end of the Great Recession." Furthermore, the "decline of summer jobs is a specific instance of a broader long-term decline in overall youth employment, a trend that's also been observed in other advanced economies." If the trend continues, even fewer applicants will bring previous job skills with them into a writing center.

To lessen the focus on soft skills in the hiring process, however, is not to lessen their importance in the work of a writing center. Rather, it is instead to solidify the idea that they become a skill that should be explicitly taught as part of writing center practice. As Earles and Ryan claim, it is "our responsibility to make professionalism more transparent" for the tutors.

To lessen the focus on soft skills in the hiring process, however, is not to lessen their importance in the work of a writing center. Rather, it is instead to solidify the idea that they become a skill that should be explicitly taught as part of writing center practice. As Earles and Ryan claim, it is "our responsibility to make professionalism more transparent" for the tutors.

A Modified Approach

For the past few years, the seniors in the Wittenberg Writing Center have been responding to an exit survey, and one of the questions is what they would change about the Writing Center if they could. Every year, some of them mention how we might improve soft skills. For example, they suggest that I remind advisors of what topics are appropriate for the front room and what is appropriate attire for work; they ask me to remind advisors of how to positively approach writers when they walk in the door; one recently suggested that he "would absolutely require that all advisors smile." He argued that "smiling is infectious, and it dispels anxiety." These suggestions address professionalism and positive attitude, two of the top soft skills mentioned by Robles. Other comments often focus on work ethic and responsibility�the seniors want the incoming advisors to realize their writing center work takes precedence over other obligations.

These comments come even though every advisor has been given a handout with job expectations and the following blurb:

As an advisor, you are a professional. The Writing Center gives you a great deal of responsibility. We trust you to arrive promptly at all your scheduled hours. If for some reason you cannot make an occasional appointment, you are responsible for notifying us early and for finding your own replacement from among the other advisors. We expect you to work hard at your job. When you are not advising, you may spend your scheduled time reading about teaching writing or writing materials for us to use. Above all, you must treat all visitors to the Writing Center with sensitivity. Be friendly and supportive. Carry that sense of the Writing Center as a supportive place away with you too. Be very careful about what you say about your work. Never talk about advisees outside of the Writing Center�even when the remarks are general and leave out names. You have a privileged relationship with your advisees and you are bound to maintain confidentiality.

From my perspective, it does not seem that there is always "automatic triggering" in our writing centers with regard to soft skills. Nor do I think tutors will automatically take such skills with them into other areas of their lives. But it does seem possible for administrators to do more to help them, in Perkins and Salomon's phrasing, to start "bridging" between the writing center and future situations. Such work is especially important for administrators of centers like mine, where none of the advisors plan to work in the writing center field. It is imperative that I do as much as possible to prepare these students for their upcoming professions, and professional development means preparing them for law school, for interviews, for graduate programs in history or psychology, for internships, for government positions.3 How can I best do that?

|

| Figure 3. Green highway sign with "High Road" going one way and "Low Road" going the other. |

For starters, I can take the high road, and think about high road transfer. Rather than assuming that advisors will make an "obvious" connection between the soft skills in a writing center and future situations, I can deliberately push them to consider how they can transfer such abilities and habits. I can design what Perkins and Salomon call "forward reaching" high road transfer opportunities, in which "one learns something and abstracts it in preparation for applications elsewhere" (26). This could be something as simple as having advisors introduce themselves in our training class�ask them to stand up, shake hands, look each other in the eye, give their names�and then discuss how they might greet writers who enter the writing center. Of course, that greeting itself is fraught with cultural implications and assumptions, and we could also take time to unpack how many differences there might be in how people greet one another.4 The greeting is an exercise that we currently have in our class (figure 4). We also practice giving tour speeches, and we talk explicitly about standing up when a tour comes into the room, about coming around the desk to say "hello," about speaking clearly and confidently, about speaking directly to the potential students.

We do have a contract at our writing center (Appendix A), and it has been redesigned in the past few years to highlight professional behavior. In addition, we now spend time in the course going over the contract, being specific about each bullet point: what does it mean to have respect for every writer? How would we show that respect? (Earles and Ryan describe their process of having their tutors design their own Code of Professionalism, and that would be an excellent next step for our contract�what would the advisors decide if they had the choice of what to include.)

| Figure 4. YouTube video entitled "How to Shake Hands and Introduce Yourself." |

I have also redesigned the senior exit survey (Appendix B). Inspired, certainly, by the work of Hughes, Gillespie, and Kail, the survey has always had questions such as "To what extent do you think your own writing has been influenced by your experience as a writing advisor? Please explain." Now, though, alongside questions about writing is a more general one about the future: "How do you think this work [in a writing center] might help/hinder you in your future endeavors?" It is in the answers to this question that mention of soft skills comes up most frequently; it is here that the advisors are pushed to think about their work in deliberate ways.

For example, one recent senior advisor wrote:

In terms of helping my future endeavors, I certainly think that working here has made me better at collaborative work. . . . now that I've done so many sessions, I've found that considering interpersonal power/authority dynamics is one of the most important parts of collaborative work. Learning when it's appropriate to negotiate with others, take control of a situation/idea, or yield to someone else is a [practical] skill in numerous contexts outside of the Writing Center. Furthermore, I've worked with so many different personalities in this job that I feel prepared to work with just about anyone, so in that way I've gained a great deal of flexibility and adaptability.

Here is an emphasis on the collaboration, or teamwork aspect, of writing center work, as well as flexibility, both of which are valuable soft skills for employers. Also, this response reflects the "long-term enculturation" that Doug Brent speaks of, enculturation that comes from "experiences that are aimed not at providing modules of transferable knowledge but at creating a deep well of expertise and enculturating students into the long-standing mental habits, or dispositions, that will enable them to use that expertise in new situations" (411). This student seems prepared to move from one workplace to another, drawing from her writing center expertise.

Another senior wrote about reading other people, an echo of what Lape was hoping to teach her students about emotional intelligence:

I've learned a lot about how to communicate effectively with others. But I've also learned a little bit about reading others. For example, I've had a couple sessions where the writer was saying one thing but his or her facial expressions/mannerisms were telling me something else. Thus, I had to tailor my responses to fit them. In real life, I think this happens a lot. We try to hide the truth in conversations with people, choosing to close ourselves off to them. But as an advisor, I've had to learn how to look past that wall to the invulnerability in writers. I've learned how to be a friend, to be an empathetic ear letting them share with me how they're truly feeling. And I'm not sure everyone has that ability in the real world.

The advisor seems to have reached beyond the workplace to consider how her work will affect her personal life, too. (Gillespie, Kail, and Hughes also noted how tutors reported writing center work positively influenced their personal relationships.)

And a third advisor took note of Seemiller and Grace's ideas about how our communication process is changing:

And a third advisor took note of Seemiller and Grace's ideas about how our communication process is changing:

We [advisors] know how to listen, a skill becoming less and less common in the digital age. We know how to collaborate and work together to make ideas better. We understand the value of teamwork and customer service. We know how to talk to people. We can wrap our brains around ideas and concepts and provide fresh, invested, detailed perspectives. We are always working on improving. More than that, our emphasis on the writer (not the writing) has given us lots of experience with people-centered work. We talk through the complexities of language and shared meaning.

Again, soft skills like teamwork, communication, and collaboration are emphasized in the advisors' survey response. Now I want to make those skills more apparent to the advisors during their time in the writing center, not just at the end of their advising careers. I want them to uncover, and discover, all the soft skills they are using when working with writers.

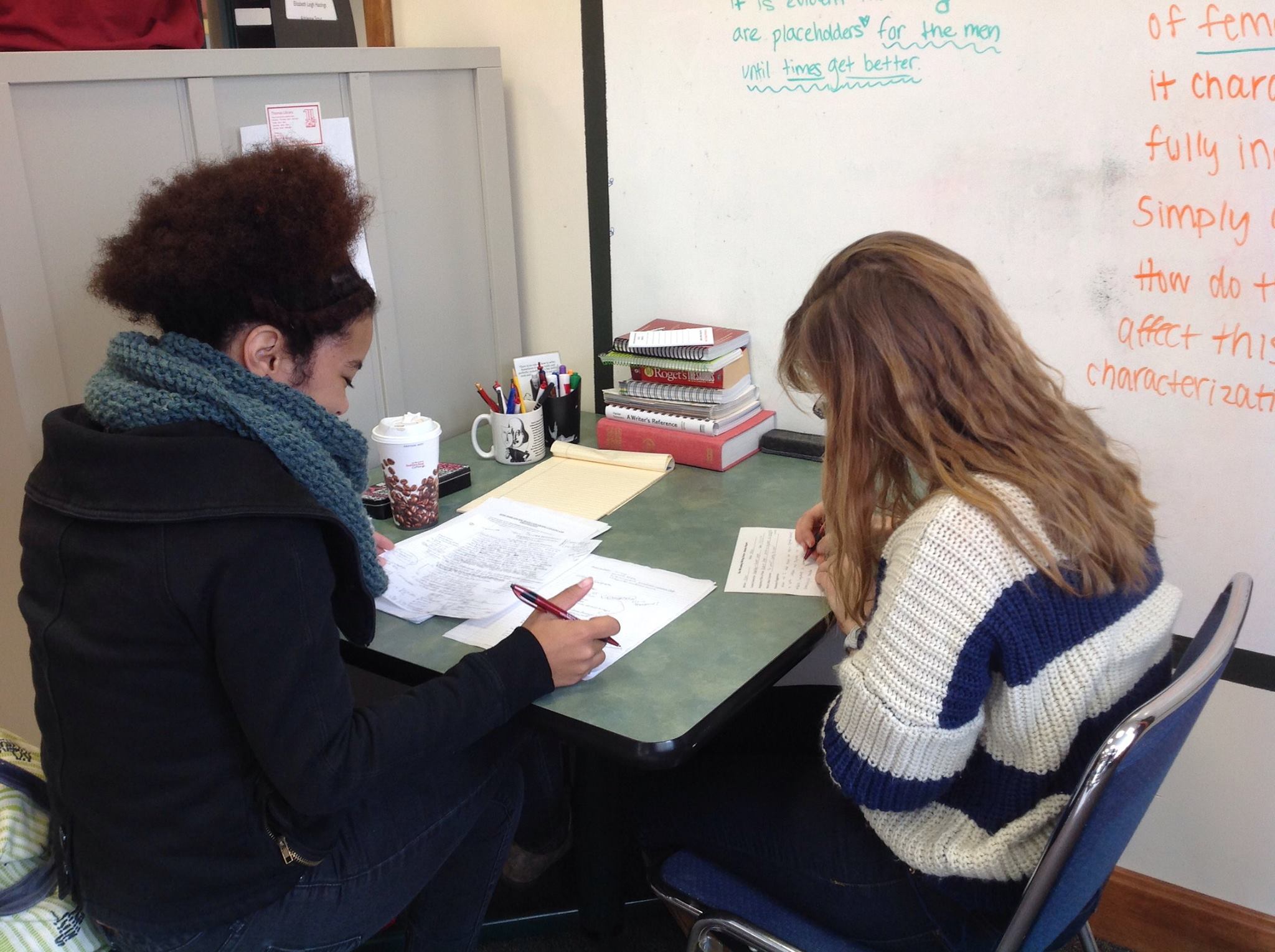

|

| Figure 5. Photo of a tutor and a writer at a table. |

"We know how to talk to people. We can wrap our brains around ideas and concepts and provide fresh, invested, detailed perspectives."

Such a goal, though, might seem yet another item added to an already-full docket for writing center directors. Some might argue that directors already focus on many of these skills, perhaps most obviously when we role play and work on addressing writers' concerns�emotional as well as textual. Yes, we do. But, at least in my center, we don't always allow them the attention (or the practice) they deserve. To do so, though, doesn't mean a monumental shift in pedagogy. After all, when you're traveling, even a one-degree change in direction will lead to a completely new destination. As I've already mentioned, we do discuss (and practice) how to greet other people in our writing center course. We practice handshakes and eye contact. We practice giving tour speeches and classroom presentations. I have also placed a list of soft skills on the syllabus as part of our learning goals (Appendix C); students should know from the beginning of the year that developing these skills are desirable outcomes, and we can discuss what they believe they bring with them and what they might want to work on.

Table 1

A list of suggestions for foregrounding soft skills in the writing center

I also send out weekly emails that include quick articles about professional behavior; the articles might range from how to manage your time at work (and in life) to how to ask for a raise. The advisors have often commented on how much they appreciate the pieces. Most are quick reads, a short overview of an idea or approach, and many also adopt a more humorous tone. For example, Drew Magary has an article in GQ titled "How to Be a Professional" that sharply advises readers to do things such as be on time, shower regularly, get back to people, don't burn bridges, and own your f***-ups. It is advice that articles offer again and again, but the edgier tone can be appealing.

I have also started to have pre-semester conferences with each tutor�we are closed the first week of the semester and can schedule these meetings then. In that meeting, I have been asking each tutor about their goals: for the semester, for the year, and for their future. I have then intentionally been asking how their work in the writing center can help them achieve those goals. As often as possible, I link what they do in the center with what they might be asked to accomplish in the future. This is another step in my trying to follow what Brent has called the "surprisingly consistent" (416) messages about transfer. Even though scholars might disagree about many points, there does seem to be agreement that transfer requires "an emphasis on learning fundamental principles, on being mindful, on explicitly cuing learners to help them make connections that might otherwise elude them, and on mentoring and providing scaffolding to help them survive the shock of boundary crossing" (416). Although these messages ring true for hard skills, I believe they are just as relevant for soft skills. The more we can help tutors learn the fundamental principles of soft skills and cue them to make connections between our workplace situations and others, the better prepared they will be to take the high road and transfer those skills from one area of their lives to another.

NOTES

1 (back to text)

We use the term "advisor" at Wittenberg, and I use that term when referring to anyone on our staff, but the term "tutor" when referring to writing center staff in general.

2 (back to text)

Please see Devet's article for a full explanation of each of these types of transfer. My goal here is not to re-define the types, but rather to make the point that the examples given for each focus on hard skills rather than soft skills.

3 (back to text)

For me, this is one of the many wonderful aspects of writing center work, especially surrounded as we often are by other academic disciplines. We are one of the few fields in which we are training people to be proficient in areas that we do not study. Other departments prepare lawyers or doctors or historians or literary critics or biologists�we prepare them all.

4 (back to text)

As one reviewer of this piece noted, "handshaking and looking someone in the eye may be an interestingly masculine example. In the U.S. culture, women aren't encouraged to shake hands as much as men are. Not so in Scandinavia, of course, and I was taught to shake hands with people as a child, but I've been told by some that 'women don't do that except in business situations.'"

Works Cited

Brent, Doug. "Transfer, Transformation, and Rhetorical Knowledge: Insights from Transfer Theory." Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 25, no. 4, 2011, pp. 396-420.

Cobb, Loretta, and Elaine Kilgore Elledge. "Undergraduate Staffing in the Writing Center." Writing

Centers: Theory and Administration, edited by Gary A. Olson, NCTE, 1984, pp. 123-131.

Cukier, Wendy, et al. "'Soft Skills are Hard': The Skills Gap and Importance of Soft Skills." n.d. http://www.ideas-idees.ca/sites/default/files/sites/default/uploads/general/2015/sshrc-ksg-cukier.pdf. Accessed 28 Feb. 2018.

Desilver, Drew. "In the U.S., teen summer jobs aren't what they used to be." Pew Research Center. 27 June, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/27/teen-summer-jobs-in-us/.

Devet, Bonnie. "The Writing Center and Transfer of Learning: A Primer for Directors." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 1, 2015, pp. 119-151.

Dinitz, Susan, and Jean Kiedaisch. "Tutoring Writing as Career Development." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 34, no. 3, 2009, pp. 1-5.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn. "Building Connections and Transferring Knowledge: The Benefits of a Peer

Tutoring Course Beyond the Writing Center." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 1,

2015, pp. 153-181.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Sarah Harcourt. "Training vs. Learning: Transfer of Learning in a Peer Tutoring

Course and Beyond." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 36, no. 7-8, 2012, pp. 1-6.

Earles, Tom, and Leigh Ryan. "Teaching, Learning, and Practicing Professionalism in the Writing Center." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen Gabrielle Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck. 2019.

Fitzgerald, Lauren, and Melissa Ianetta. The Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors: Practice and Research. Oxford UP, 2016.

Gillespie, Paula, and Harvey Kail. "Crossing Thresholds: Starting a Peer Tutoring Program." The Writing

Center Director's Resource Book, edited by Christina Murphy and Byron L. Stay, Erlbaum, 2006, pp. 321-330.

Green, Ann E. "Notes Toward a Multicultural Writing Center: The Problems of Language in a

Democratic State." Still Seeking an Attitude: Critical Reflections on the Work of June Jordan, edited by Valerie Kinloch and Margaret Grebowicz. Lexington, 2004, pp. 101-13.

Hughes, Bradley, et al. "What They Take With Them: Findings from the Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 30, no. 2, 2010, pp. 12-46.

Lape, Noreen. "Training Tutors in Emotional Intelligence: Toward a Pedagogy of Empathy." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 32, no. 2, 2008, pp. 1-6.

Magary, Drew. "How to Be a Professional." GQ.com 13 March, 2019. Accessed April 15, 2019.

Moss, Philip, and Chris Tilly, "'Soft' Skills and Race: An Investigation of� Black Men's Employment Problems." Work and Occupations, vol. 23, no. 3, 1996, 252-76.

Muldoon, Andrea. "So, You helped Create a New Writing Center�Now what?: Lessons and Reflections from a First-Year Director." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 32, no. 7, 2008, 1-6.

Perkins, D. N., and Gavriel Salomon. "Teaching for Transfer." Educational Leadership, vol. 46, no. 1,

pp. 22-32.

Puma, Vincent. "The Write Staff: Identifying and Training Tutor-Candidates." Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 14, no. 2, 1989, pp. 1-4.

Robles, Marcel M. "Executive Perceptions of the Top 10 Soft Skills Needed in Today's Workplace." Business Communication Quarterly, vol. 75, no. 4, pp. 453-65.

Seemiller, Corey, and Meghan Grace. Generation Z Goes to College. Josey-Bass, 2016.

Sheridan, Rick. "STEM is smart, but soft skills matter." Editorial. Springfield News-Sun [Springfield, OH],

6 June, Op-Ed, 2017, p. A7.

Vance, J.D. Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. HarperCollins, 2016.

BIO

Mike Mattison currently is Director of the Writing Center and Associate Professor of English at Wittenberg University, and he previously directed the Writing Center at Boise State University. When not collaborating with tutors and writers, he engages in heated games of Catchphrase with his family.