CHAPTER FOUR

Teaching for Transfer and the Design of

a Writing Center Education Program

TRANSFER OF LEARNING IN THE WRITING CENTER

Lauren Marshall Bowen

University of Massachusetts Boston

Matthew Davis

University of Massachusetts Boston

Although writing center scholarship has recently taken up the theoretical framework of learning transfer, in point of practice, Bonnie Devet argues writing centers "already teach for transfer every day" (120). For tutors, high-road transfer is of particular importance. Unlike low-road transfer, or the automatic transfer of skills triggered by a familiar context or prompt (e.g., reflexively knowing how to drive a truck because you already know how to drive a car), high-road transfer involves "the explicit conscious formulation of abstraction in one situation that allows making a connection to another" situation (Salomon and Perkins 118). That is, high-road transfer is more similar to recalling the Pythagorean theorem you learned in school and using it at home to calculate the maximum size television you can purchase to fit in a particular space. High-road transfer is especially valuable to tutor education for two reasons. First, tutors must learn to make meaningful, adaptable use of prior writing knowledge and writing practices (both writers' and their own) to suit the diverse writers, texts, and circumstances of tutorials. Second, centers treat learning dynamically, as a process "located in the changing relationship between persons and activities," rather than focusing only on "fixing" an isolated problem (Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström 27). By contrast, tutoring that relies on habituated, unconscious, low-road transfer would subvert writing center pedagogy's investments in writing and learning as situated in diverse social contexts, as such forms of transfer don't sufficiently support adaptability. Thus, for tutors to recognize and respond to the socially situated nature of their work, tutor education programs should be designed to facilitate high-road transfer of writing, tutoring knowledge, and practices in order to promote not "tutor training," but "tutor learning" (Driscoll and Harcourt 1).

We argue that the Teaching for Transfer (TFT) curriculum—as designed by Kathleen Blake Yancey, Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak and described in Writing Across Contexts, which has since been researched through empirical work across institutional contexts (Yancey, writing.across.contexts)—can be productively taught through writing center pedagogy to foster tutors' high-road transfer. In this chapter, we present a theoretically grounded pedagogical extension of this TFT curriculum in order to consider two related questions:

1. How can the TFT curriculum be adapted for tutor education?

2. How does the context of the writing center most productively shape the design of a TFT curriculum and guide our research about it?

Grounded in the empirical studies of the TFT curriculum (Tinberg; Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts; Yancey et al., "Writing Across College"; Yancey et al., "Teaching"; Andrus et al.), we consider the questions above as a way to explore how we might think in theoretically grounded, rigorous ways about adapting and contextualizing the TFT curriculum for tutor learning. We address these questions by briefly overviewing the TFT curriculum, identifying some core elements of writing center pedagogy that help to contextualize the TFT curriculum, outlining three curricular features for adapting the TFT curriculum for a tutor education seminar, and then pointing to several ways forward in the research and teaching of transfer-oriented tutor learning curricula. In proposing this theoretical course design, we highlight ways that TFT and writing center pedagogy can inform, challenge, and expand each other.

Grounded in the empirical studies of the TFT curriculum (Tinberg; Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts; Yancey et al., "Writing Across College"; Yancey et al., "Teaching"; Andrus et al.), we consider the questions above as a way to explore how we might think in theoretically grounded, rigorous ways about adapting and contextualizing the TFT curriculum for tutor learning. We address these questions by briefly overviewing the TFT curriculum, identifying some core elements of writing center pedagogy that help to contextualize the TFT curriculum, outlining three curricular features for adapting the TFT curriculum for a tutor education seminar, and then pointing to several ways forward in the research and teaching of transfer-oriented tutor learning curricula. In proposing this theoretical course design, we highlight ways that TFT and writing center pedagogy can inform, challenge, and expand each other.

The Teaching for Transfer (TFT) Curriculum in Composition

|

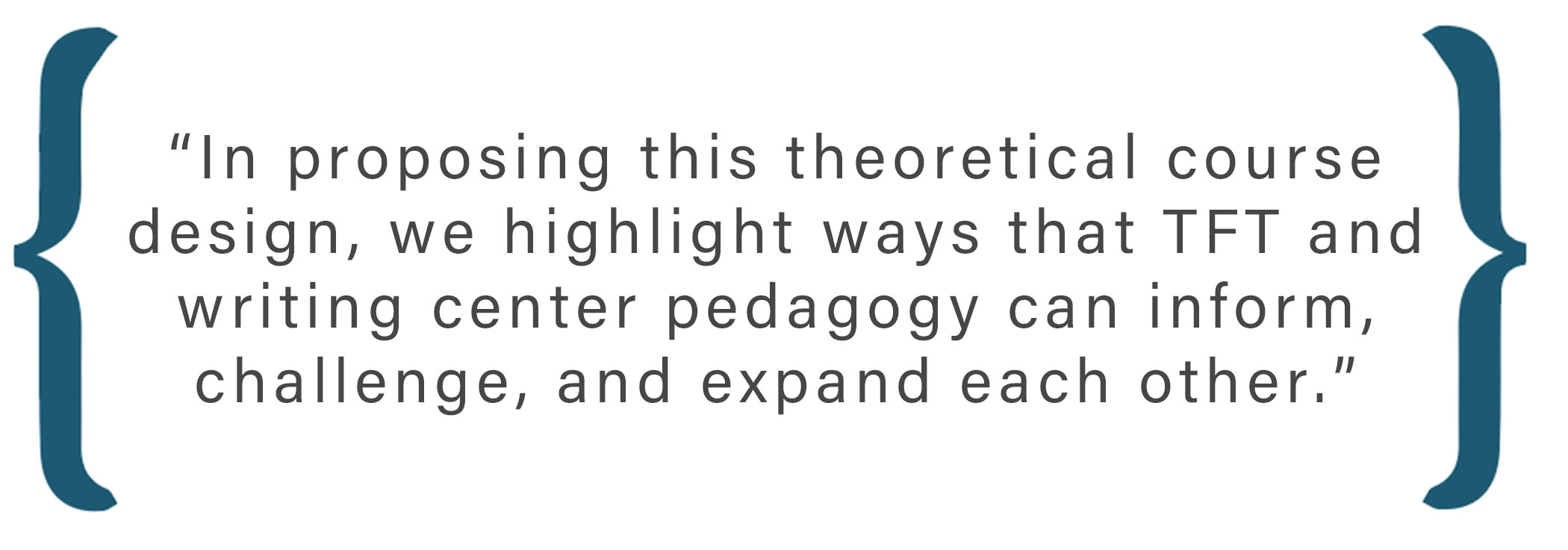

| Figure 1. The three interlocking, interdependent features of the TFT curriculum, per Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts. (Image credit: Matthew Davis) |

Although several composition curricula exist with writing transfer as their central focus (Dew; Downs and Wardle; Nowacek), the Teaching for Transfer (TFT) curriculum provides conceptual grounding for the transfer of writing practice and knowledge that has been formally researched across eight different colleges and universities (Yancey, writing.across.contexts). The TFT curriculum has three interlocking, interdependent content features: one, the reiterative practice of reflection; two, a set of key terms for students to learn and apply; and, three, a Theory of Writing assignment (Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts 57). These three features, which form the core of the TFT curriculum, can be taught by teachers and programs in ways that are sensitive to local contexts.

1. Reflection. Reflection is the mode of thinking and action tying together all of the TFT curriculum. Within TFT, reflection is a systematic, reiterative activity that prompts students to conceptualize their developing knowledge about and practice with writing and its relationship to themselves as writers. Students (a) encounter reflection through course readings and discussion, (b) practice it in course activities where they share and revisit their previous thinking, and, (c) through assignments that ask students to write about their insights about themselves as writers, formalize their thinking in what Kathleen Yancey calls "reflections-in-presentation" (Reflection). For example, several times during the semester, students respond to reflective questions, such as "What kind of writer are you?" and "What previous knowledge about writing have you used in this class? What knowledge have you developed that you think will be useful in future courses?" Through this thinking and practice, reflection within the TFT curriculum is explicit, intentional, integrative, and reiterative.

2. Key terms. Additionally, a set of eight writing-related key terms comprise the content of TFT: rhetorical situation (including exigence), audience, genre, context, reflection, knowledge, purpose, and discourse community. Yancey, Robertson, and Taczak find that understanding and using these eight key terms fosters transfer because these terms are most salient to students' work across writing contexts. Terms are introduced to students in sequenced clusters, and each term contributes to the introduction of subsequent terms (Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts 57). In connecting to course readings, these terms are the content students use for their thinking, writing, and reiterative reflection throughout the TFT curriculum (5).

3. Theory of Writing. Finally, the Theory of Writing (ToW) is the signature assignment for the TFT curriculum and is a long-form written reflection-in-presentation, Yancey's term for a formal reflection as composed for an evaluative audience (Reflection). This assignment prompts students to integrate what they know—from prior experience, course readings, and their own previous writing experiences, among other sources of knowledge. To do so, students revisit their own work from the course to theorize what writing is, how it works, how one does it, and what their theorizing of writing means to them. The ToW "helps students create a framework of writing knowledge and practice they'll take with them when the course is over" (Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts 57).

Taken together, the three features of the TFT curriculum—meaningful reflection, learning and applying the key terms, and the ToW assignment—encourage transfer of writing knowledge and practice because student writers create a conceptual framework integrating prior and new knowledge for concurrent and future writing situations (Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts 103-28).

The concerns of the TFT curriculum are familiar to writing center studies through other transfer focused curricula. For instance, Dana Lynn Driscoll and Sarah Harcourt's transfer-oriented curriculum similarly focuses on connections across writing situations, metacognitive reflection, and building transferable knowledge. Both TFT and Driscoll and Harcourt's curricula focus on course readings examining transfer, feature student texts as objects of reflective attention, and stress that writing pedagogy is about learning, not training. Though both curricula circulate in the field, TFT has been taught and studied across a greater range of curricular contexts and institutional types (Yancey, writing.across.contexts). In addition, TFT offers a structure that is adaptable and sensitive to context: theories of writing can be retooled in terms of scope and focus, the key terms can be expanded, and reflection can be oriented toward different contexts. Recontextualized for tutor education, then, the TFT model provides curricular shape and content organization to reflect and amplify existing values of writing center pedagogy—values we outline in the next section.

The concerns of the TFT curriculum are familiar to writing center studies through other transfer focused curricula. For instance, Dana Lynn Driscoll and Sarah Harcourt's transfer-oriented curriculum similarly focuses on connections across writing situations, metacognitive reflection, and building transferable knowledge. Both TFT and Driscoll and Harcourt's curricula focus on course readings examining transfer, feature student texts as objects of reflective attention, and stress that writing pedagogy is about learning, not training. Though both curricula circulate in the field, TFT has been taught and studied across a greater range of curricular contexts and institutional types (Yancey, writing.across.contexts). In addition, TFT offers a structure that is adaptable and sensitive to context: theories of writing can be retooled in terms of scope and focus, the key terms can be expanded, and reflection can be oriented toward different contexts. Recontextualized for tutor education, then, the TFT model provides curricular shape and content organization to reflect and amplify existing values of writing center pedagogy—values we outline in the next section.

Teaching for Transfer and Writing Center Pedagogy

Before we specify the ways a TFT curriculum might be enacted and extended by writing center pedagogy, it is appropriate to summarize what we see as some fundamental loci of interest espoused by writing center pedagogy. Given that writing center tutor education is necessarily informed by the particulars of institutional context, a focus on interactions between tutors and writers is the closest we might come to identifying a universally shared condition of all tutoring programs. Consequently, a social conception of writing and learning is vital to writing center pedagogy (Ede). As Neal Lerner suggests, this core belief in writing as social interaction informs writing center pedagogy through two fundamental claims: first, writing is rhetorical; and second, language and literacy involve socialization and collaborative learning (305-307).

The social nature of writing itself provides a basis for tutors to engage with writers' socially situated learning; in addition, writing center pedagogy recognizes that tutors' learning is itself also social and situated: tutors learn how to be tutors through interactions with tutors, instructors, administrators, and writers. Particularly influential for framing the social, situated, and distributed nature of tutor learning has been Etienne Wenger's concept of "community of practice," which is a group of people who learn together while engaging in a shared project, goal, or endeavor (e.g., Geller et al.). In Wenger's approach, learning occurs when members of a community of practice exchange and collaborate consistently, over a period of time (45). These interactions among members of a community of practice start to develop patterns, which become the practices that can provide a "source of coherence" for the community—a sense of belonging and shared purpose that helps to advance collective learning (49). However, because communities and their practices are always unstable and emergent, newcomers participate in a manner that further shapes the community's practices. Newcomers' perspectives, if and when they gain sufficient traction, expand and shape a discourse community's collective knowledge and practices.

The social perspective of writing center pedagogy—both as an emergent outcome of the writing center community of practice and as a deliberate framework for curricular design—necessarily prepares tutors for responding to the social realities that surround and infuse tutorial exchanges. Most notably, writing center pedagogy informs tutors' encounters with systems of power, multilingualism, and multimodality. In highlighting these three key components of tutor learning, we indicate a loose consensus among writing center scholars and practitioners that these aspects of tutor learning—though, of course, not only these—are fundamental to tutoring. Thus, these points of consensus should feature in any tutoring curriculum, including those that teach for transfer. Below, then, we elaborate briefly on each of these three aspects of tutor learning, tracing first the demands they place on any tutor education curriculum before proceeding to explore how they shape a contextualized adaptation of TFT.

Power

Although tutors "inhabit a world somewhere between student and teacher" (Harris 28), the institutional setting of the tutorial scene can reproduce the authority structure of teacher-to-student (Dyehouse 57), which can replicate other social hierarchies. Given this tendency, an ethics of tutoring includes methods for examining the politics of tutoring through the critical lenses of identity categories, such as race (Greenfield and Rowan), sex and gender (Rafoth et al.), sexuality (Denny), and disability (Kiedaisch and Dinitz).

Multilingualism

Writing center scholars regularly frame writing centers as linguistic contact zones (Bawarshi and Pelkowski; Harris; Lerner). This framing draws on Mary Louise Pratt's well-known term for social spaces in which cultures meet, mix, and/or clash, often across uneven power relationships. In writing centers, this means that, through collaborative learning, writers can learn to use "the colonizer's language and verbal repertoire" to respond, with authority, to "representations others have made of them" (Pratt 35-6). Concurrently, in the center, "literacy practices reproduce the social order and regulate access and subjectivity" (Grimm 5). Given the political knife's edge upon which tutor-writers interact, writing center pedagogy must account for "the operation of language across lines of differentiation, focusing on the nodes and zones of contact between groups" (Harris 37).

Multimodality

Acts of composing are not separable from the material mechanics of tools and their use (Sheridan 76). While attending to the social, cultural, and individual dimensions of literate activity, writing center pedagogy also involves the materiality of rhetorical work. Tutors, therefore, need strategies for considering the production and design of texts beyond the written word, for understanding the affordances and constraints of word processing or source documentation software, and for meaningfully integrating language with other modes, including image and sound.

To help tutors think through such complex dynamics, writing center pedagogy should provide tutors with a framework within which they can learn and develop habits of mindful abstraction. And given the need for a dynamic, socially grounded approach to helping student writers work across composing contexts, this framework should be geared toward writing transfer. To evidence these claims, we present, in the next section, an overview of a TFT curriculum, as adapted for a writing tutor education course.

The TFT Curriculum as Animated by Writing Center Pedagogy

Throughout this chapter, we describe the TFT curriculum as something which needs to be animated by particular pedagogies, as well as adapted to suit particular learning contexts. The cross-institutional successes of the TFT curriculum for first-year composition indicate that the TFT curriculum is widely adaptable. In this section, we outline ways in which writing center pedagogy can animate the TFT curriculum. To illustrate this potential, we will broadly outline an adaptation of the TFT curriculum for delivery in the tutoring education context with which we are both most familiar: English 459/667: Seminar for Tutors, a combined, full-credit undergraduate- and graduate-level seminar that tutors must complete during their first semester of tutoring at the University of Massachusetts Boston. This framework would need to be further adapted and developed to suit the specific contexts of other tutor education programs.

In what follows, we describe the features of the TFT curriculum, one at a time; however, as will become apparent, the three features are interdependent and necessarily operate as interlocking concepts and practices.

Curriculum Feature 1: Reflection

Reflection has long played a central role in tutor education (e.g., Bell; Hall; Okawa et al.), primarily as a form of self-evaluation. This emphasis parallels process-based approaches to reflection in the writing classroom, which prompt students to comment on their composing choices. Robertson and Taczak's work on the TFT curriculum found that, though attention to process is helpful for learning transfer, reflection on process is best accompanied by reflection that (a) reiteratively prompts students to make connections across writing contexts; (b) systematically involves and is shaped by an evolving conceptual framework; and (c) is explicitly and deliberately integrated into the curriculum. This model of reflection, which encourages "mindfulness" and "active self-monitoring," is well-suited to facilitate high-road transfer (99). In other words, while reflection on process alone helps students to learn, the reiterative, systematic, integrated, and deliberate reflective framework of TFT helps students to think about their own learning and prepare to adapt it for new contexts (99).

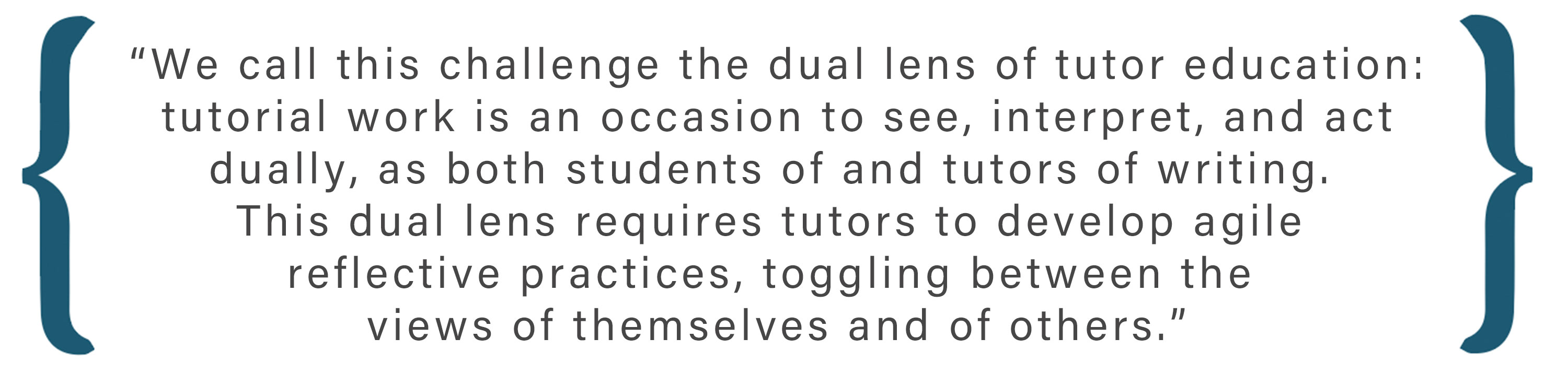

However, unlike first-year writing students, tutors simultaneously develop their own writing knowledge and practice and develop and employ tutoring strategies to guide others' learning transfer. We call this challenge the dual lens of tutor education: tutorial work is an occasion to see, interpret, and act dually, as both students of and tutors of writing. This dual lens requires tutors to develop agile reflective practices, toggling between the views of themselves and of others. One way the TFT model supports this agility is through multidimensional reflective approaches. Taczak and Robertson, drawing on concepts from Salomon and Perkins, describe these approaches in directional terms:

However, unlike first-year writing students, tutors simultaneously develop their own writing knowledge and practice and develop and employ tutoring strategies to guide others' learning transfer. We call this challenge the dual lens of tutor education: tutorial work is an occasion to see, interpret, and act dually, as both students of and tutors of writing. This dual lens requires tutors to develop agile reflective practices, toggling between the views of themselves and of others. One way the TFT model supports this agility is through multidimensional reflective approaches. Taczak and Robertson, drawing on concepts from Salomon and Perkins, describe these approaches in directional terms:

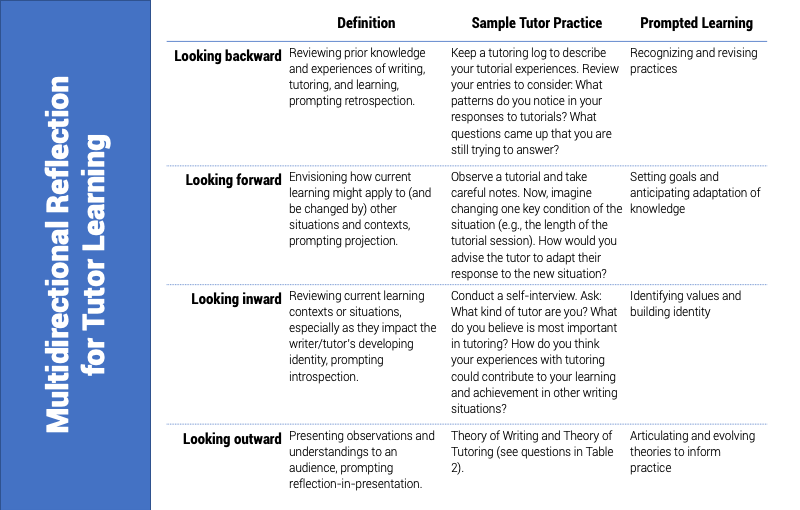

- Looking backward: reviewing prior knowledge and experiences of writing, tutoring, and learning, prompting backward-reaching transfer, or retrospection.

- Looking forward: projecting how current learning might apply to (and be changed by) other situations and contexts, prompting forward-reaching transfer, or projection.

- Looking inward: reviewing current learning contexts or situations, especially as they impact the writer/tutor's developing identity, prompting introspection.

- Looking outward: focusing on an audience-oriented presentation of tutor observations and understandings, especially to theorize writing, tutoring, and reflection's impact on both, prompting reflection-in-presentation. (46)

These reflective approaches can be combined in developing activities. For example, an inward-and-forward reflective exercise might ask tutors questions such as: What type of tutor are you? What do you believe is most important in tutoring? How do you think your experiences with tutoring contribute to your learning and achievement in other writing situations? (See questions in table 1.) The "360-degree, reiterative approach" to reflection outlined in Table 1 below helps tutors to develop as tutors/writers and as "thinkers about writing" and tutoring (Taczak and Robertson 46). Ultimately, the TFT curriculum provides tutor education with an extensive method for tutors to achieve a well-rounded, reflective approach to their practice of tutoring for transfer.

Table 1

Multidirectional reflection for tutor learning, offering definitions, examples, and learning outcomes of the four reflection types described by Taczak and Robertson's "360-degree, reiterative approach." (46)

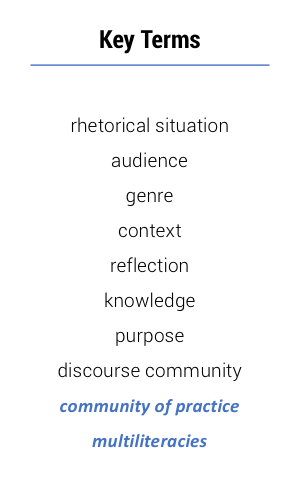

Curriculum Feature 2: Key Terms

A central finding of the TFT research is that the role of content in a curriculum matters to the transfer of writing knowledge and practice (see Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts, chapter 3); specifically, this research finds that students "need a vocabulary for writing in order to articulate knowledge and ensure more successful transfer" (101). As we described in the introduction, high-road transfer processes like mindful abstraction—that is, the "deliberate . . . effort" of "reaching mentally"—need support (Perkins and Salomon, "Teaching" 25). One way to encourage high-road transfer is through the use of what Anne Beaufort—borrowing from Perkins and Salomon ("Are Cognitive")—calls "mental grippers," or concepts that help learners to actively and consciously organize what they know (151-152). However, key concepts have only "implicitly informed" tutor education in the past (Nowacek and Hughes 171). TFT's use of stable key terms provides a much-needed opportunity for tutors to develop flexible conceptual frameworks–that is, a vocabulary—to prompt high-road transfer more directly. The TFT curriculum's eight key terms—rhetorical situation, audience, genre, context, reflection, knowledge, purpose, and discourse community—represent core writing concepts, the "mental grippers" for organizing knowledge of writing. Genre, to take but one example, is a term that facilitates students' understanding of the rhetorical work writing does, especially as the course assignments prompt them to explore, compare, and compose a wide variety of genres (and media and modes).

However, the dual lens of tutor education—that is, the need to think both as a writer and as a tutor of writing—requires key concepts in both writing and tutoring. Fortunately, the TFT curriculum, through its treatment of key terms, is contextually sensitive and open to adaptation. Thus, to the TFT list, we add two key terms related to tutoring concepts, both drawn from the loosely shared values of writing center contexts and pedagogies that we articulated in the previous section: community of practice and multiliteracies.

|

| Figure 2. Proposed key terms for TFT in writing center education, expanded from key terms developed and tested by TFT research—see Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts; Yancey et al., "Writing." |

Community of Practice

Just as Yancey, Robertson, and Taczak find that first-year writing "students need to participate with [teachers] in creating their own frameworks for facilitating transfer" (33), so should tutors strike a stance both as researchers and contributors to the writing center. The addition of community of practice to the set of key terms encourages tutors to see themselves, student writers, and writing center directors as a community of practice: as "learners on common ground" (Geller et al. 7). Further, given the sense that all members of the writing center are, by nature, collectively learning, the key term community of practice creates an opportunity for tutors to adopt (and model for student writers) an openness to learning transfer. In other words, tutors can assume the "novice-as-expert" stance that involves behaving as a learner/researcher first and embracing ambiguity rather than certainty (Sommers and Saltz), thereby modeling for student-writers dispositions that facilitate transfer. When considered alongside rhetorical situation and discourse community, a term like community of practice invites conceptual tension, prompting students to consider how and when these concepts are, or are not, compatible. Prompting tutors to explore this tension encourages them to develop a sense of the distinctions among these concepts, and by extension, the distinctions and connections between a theory of writing and a theory of tutoring (which we discuss below).

Multiliteracies

The New London Group's well-known concept of multiliteracies—a term sometimes adopted to rename writing centers as multiliteracy centers (Balester et al.)—highlights two key considerations for writing center work in a globalized, networked world: first, the rapid evolution of language use through the flows of people and culture in globalized societies, and second, the "variety of textual forms" (not limited to alphabetic language) that new media calls to our attention (61). The term multiliteracies invites, in other words, considerations of writing as both multilingual and multimodal. We take up the multilingual considerations of TFT in the conclusion. Here, however, we note that the multimodal component of multiliteracies is already inherent within the TFT curriculum, which invites students to explore different modes, media, and genres beyond the academic essay. It is by exploring multimodality across contexts, including digital composing environments, that students develop a facility for high-road transfer. (The TFT assignments that evidence this openness are available in the Appendices to Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts.) Other variations of TFT, such as those in professional writing, include specifically digital, web-design assignments. In short, focusing on multiliteracies provides tutors another way to engage the duality of writing center work: first, to develop ways of working across languages and modes, transferring what they know about print literacy, for instance, into digital composing; and, second, to help others learn to navigate ways of communicating in a multilingual, networked world.

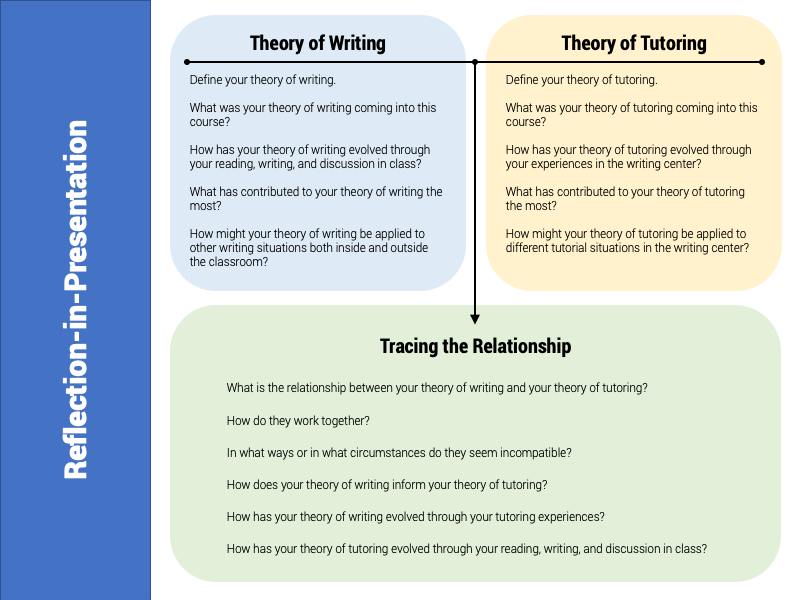

Curriculum Feature 3: Theory of Writing and Theory of Tutoring

The final assignment in the TFT curriculum asks students to revisit their previous reflections and other writing projects to articulate a theory of writing, engage with key concepts, and illustrate how they have developed and applied their knowledge over the semester. As a crucial step, students in a TFT course are prompted for deliberate, high-road, forward-reaching transfer through meta-questions on their theory of writing, such as: "How might your theory of writing be applied to other writing situations both inside and outside the classroom?" (Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts, 167).

This theory-making practice is ideal for tutors, who must view their work through the dual lens of writing and tutoring. Some theory of writing is necessarily embedded within tutoring practice, but tutors—even highly experienced ones—cannot always articulate their theory, nor its relationship to their tutoring practices. Thus, as animated by writing center pedagogy, this assignment prompts tutors' articulation of two theories: a theory of writing and a theory of tutoring. As a brief illustration, figure 3 below provides sample questions, adapted from Yancey, Robertson, and Taczak's original assignment (167). We propose that, by answering these questions, tutors can compose a theory of writing and a theory of tutoring, as well as articulate the relationship between them.

|

| Figure 3. Prompt questions for the reflection-in-presentation assignments for a TFT curriculum for tutor education. "Theory of Writing" prompt questions were developed by Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts; "Theory of Tutoring" and "Tracing the Relationship" prompts are our expansions for the context of tutor education. |

This reflection-in-presentation is designed to help tutors develop a mental "roadmap," which "allows one to see different locations, routes to those locations, and connections among those routes" (Yancey, Reflection; Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts 41). In contrast to a low-road transfer "GPS approach," which simply maps a specific route between point A and point B, a "roadmap" approach provides tutors with flexibility for navigating various tutorial situations.

Adapting the TFT curriculum to a tutoring course in theoretically grounded and contextually sensitive ways, as we do here, offers three advantages that extend the curricular outcomes found in the studies of TFT. First, it provides an expedient, flexible means for tutors to assess and respond to particular tutorial situations. Second, the roadmap approach gives tutors "agency in deciding where to go and how...precisely because one sees the relationships across locations" (Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts 41). Through their own theories of writing and tutoring, which tutors recognize as evolving and contextual, tutors become attuned to respond more mindfully and flexibly in tutorial interactions. A third advantage is that the theory of tutoring initiates tutors into a state of conscious accountability: as they articulate their own key rhetorical concepts and practices in a cohesive theory, tutors recognize that their theory is in dialogue with other key concepts and practices—as observable, at least, in the variation of theories of literacy that students might encounter across literate domains, including school, work, home, church, and so on (Yancey et. al., "Teaching").

We suggest that these three outcomes of the theory of writing and theory of tutoring assignments increase the likelihood that tutors will be more conscious of the need to be flexible, responsive, and ultimately accountable for their choices, part of which includes acknowledging that they always have more to learn.

We suggest that these three outcomes of the theory of writing and theory of tutoring assignments increase the likelihood that tutors will be more conscious of the need to be flexible, responsive, and ultimately accountable for their choices, part of which includes acknowledging that they always have more to learn.

The Cross-Pollination of TFT and Writing Center Pedagogy: Implications and Suggestions for Further Research and Practice

The proposed course detailed above—a TFT-focused Seminar for Tutors—is a starting point for fruitful cross-talk between TFT and writing center pedagogy, with each offering the other important opportunities to extend, reconsider, and reshape pedagogical practice. This final section suggests implications for further work on adapting TFT to tutor learning toward addressing the issues of power, multilingualism, and multimodality; it also traces implications for further research on teaching for transfer through a focus on the dual lens of tutor education.

Power

Power, though central to writing center pedagogy, is an area that TFT research has not taken up explicitly. In writing classrooms, power is most explicitly examined via critical pedagogies (including those inspired by Paulo Freire); however, because critical pedagogy delivers different content than TFT, the two might seem incompatible. That said, as animated within a writing center context, the TFT curriculum is designed for prompting students to explore writing and literacy in relation to issues of power, culture, and identity. Through the theories of writing and tutoring, which promote a conscious accountability of tutors' values, beliefs, and understandings of language and learning, the TFT curriculum urges tutors away from absolutist approaches that perpetuate erroneous—sometimes even racist and classist—views of language and culture. Thus, the TFT curriculum focuses on concept-driven theory-building that is open to critically thinking about literacy's role in forming identity and social hierarchies. Further exploration of the writing center/TFT pairing might consider how reflection and theory-making foster critical consciousness. Do concepts related to power and social identity transfer within and from a TFT-based tutor education program? How might we trace the transfer of such concepts over time, or identify them within a given context (such as tutorials)?

Multilingualism

Another aspect of writing center pedagogy that has not received direct attention in TFT is linguistic diversity. In the writing center, language variation is perhaps more visible than in the classroom, as many writers come to writing centers precisely because their language has been marked as non-normative; therefore, writing center pedagogy provides an important testing ground for two questions about TFT: To what extent does a transfer-oriented curriculum work within richly multilingual contexts? And how much, if at all, does TFT assume English-only interactions between teachers and students?

Multimodality

Writing center studies initially took up the materiality of composing and the multimodal aspects of multiliteracies with mixed feelings (see Pemberton regarding writing center work and digital texts). However, this WLN series of digital edited collections carries forward the work needed for the field to fully consider the implications of materiality, multimodality, and multiliteracies (see, for example, Clements). Able to support this ongoing multimodal work, TFT is already relatively open to materiality: the ways in which students reflect, take up and work with key terms, and theorize writing are materially open. TFT is, we argue, an open-invitation curriculum in terms of multiliteracies—and students do take it up across institutions and curricula in ways that work both translingually and transmodally. Future studies of TFT in tutor learning could contribute to—and perhaps even unify—articulations of the roles of tools, technologies, and modes in the writing center. A key remaining question is: How might tutors and writers develop and transfer what they know about composing in multiple modes during their mutual work in the writing center?

The Dual Lens of Tutor Education

While any uptake of the TFT curriculum is necessarily shaped by the context in which it is taught, the writing center poses a unique challenge of thinking about writing transfer with a dual lens—for oneself and also for others (e.g. tutees). At this point, no published studies of TFT courses have involved studying writing-at-a-remove (that is, as an observer of someone else's attempts at writing transfer in addition to one's own) inherent to tutor learning. The dual lens of tutors who must theorize writing and the tutoring of writing provides an opportunity for TFT research to consider the extent to which this duality matters. In short: How do we best educate tutors to build on and transfer what they know about writing into the tutorial, and to do so in ways that help support transfer for the writers with whom they work?

TFT Beyond the Classroom

In addition, TFT is a course-based curriculum, and thus our adaptation of it for tutor learning, is designed with a stable, full-credit seminar in mind. As many writing center directors realize, such a course is a luxury. To our knowledge, nobody has yet taught the TFT curriculum outside a course context. Therefore, another important step is to consider whether—and how—a TFT tutor education can be designed as a non-course-based curriculum. Non-course-based curricula work for writing centers in other contexts, and careful design is needed to determine whether they might for TFT as well. Additionally, researchers might examine whether that curriculum can be delivered through more dispersed points of contact, such as staff meetings, orientation sessions, tutoring logs, and other sites. In this way, writing centers with a variety of tutor education mechanisms might contribute to the areas of future research outlined above.

There is clear value in tutors' ability to articulate flexible theoretical frameworks for writing and tutoring based on the solid ground of writing research and writing center's community values. Through a TFT curriculum contextualized for writing centers, tutors prepare to meaningfully transfer and adapt their own writing knowledge and practice and, in turn, model similar transfer practices to the writers with whom they work.

Works Cited

Andrus, Sonja, et al. "Teaching for Writing Transfer: A Practical Guide for Teachers." Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 47, no. 1, 2019, pp. 76-89.

Balester, Valerie, et al. "The Idea of a Multiliteracy Center: Six Responses." Praxis, vol. 9, no. 2, 2012, www.praxisuwc.com/baletser-et-al-92/.

Bawarshi, Anis, and Stephanie Pelkowski. "Postcolonialism and the Idea of a Writing Center." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 19, no. 2, 1999, pp. 41-58.

Beaufort, Anne. Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Utah State UP, 2007.

Bell, Jim. "Tutor Training and Reflection on Practice." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 21, no. 2, 2001, pp. 79-98.

Clements, Jessica. "The Role of New Media Expertise in Shaping Writing Consultations." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen Gabrielle Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, WLN, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Clements.html.

Denny, Harry C. "Queering the Writing Center." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 30, no. 1, 2010, pp. 95-124.

Devet, Bonnie. "The Writing Center and Transfer of Learning: A Primer for Directors." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 1, 2015, pp. 119-51.

Dew, Debra. "Language Matters: Rhetoric and Writing I as Content Course." Writing Program Administration, vol. 26, no. 3, 2003, pp. 87-103.

Downs, Douglas, and Elizabeth Wardle. "Teaching About Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)Envisioning 'First-Year Composition' as 'Introduction to Writing Studies.'" College Composition and Communication, vol. 58, no. 4, 2007, pp. 552-84.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Sarah Harcourt. "Training vs. Learning: Transfer of Learning in a Peer Tutoring Course and Beyond." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 36, no. 7-8, 2012, pp. 1-6.

Dyehouse, Jeremiah. "Peer Tutors and Institutional Authority." Working with Student Writers: Essays on Tutoring and Teaching, 2nd ed., edited by Leonard A. Podis and JoAnne M. Podis, Peter Lang, 2010, pp. 57-62.

Ede, Lisa. "Writing as a Social Process: A Theoretical Foundation for Writing Centers." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 9, no. 2, 1989, pp. 3-15.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed (50th Anniversary Edition). Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. 4th ed., Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Geller, Anne Ellen, et al. The Everyday Writing Center: A Community of Practice. Utah State UP, 2007.

Greenfield, Laura, and Karen Rowan. Writing Centers and the New Racism. Utah State UP, 2011.

Grimm, Nancy. "The Regulatory Role of the Writing Center: Coming to Terms with a Loss of Innocence." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 17, no. 1, 1996, pp. 5-29.

Hall, R. Mark. "Theory In/To Practice: Using Dialogic Reflection to Develop a Writing Center Community of Practice." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, 2011, pp. 82-105.

Harris, Muriel. "Talking in the Middle: Why Writers Need Writing Tutors." College English, vol. 57, no. 1, 1995, pp. 27-42.

Kiedaisch, Jean, and Sue Dinitz. "Changing Notions of Difference in the Writing Center: The Possibilities of Universal Design." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 27, no. 2, 2007, pp. 39-59.

Lerner, Neal. "Writing Center Pedagogy." A Guide to Composition Pedagogies, 2nd ed., edited by Gary Tate et al., Oxford UP, 2014, pp. 301-16.

New London Group. "A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures." Harvard Educational Review, vol. 66, no. 1, 1996, pp. 60-92.

Nowacek, Rebecca. Agents of Integration: Understanding Transfer as a Rhetorical Act. Southern Illinois UP, 2011.

Nowacek, Rebecca, and Brad Hughes. "Threshold Concepts in the Writing Center: Scaffolding the Development of Tutor Expertise." Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State UP, 2015, pp. 171-85.

Okawa, Gail Y., et al. "Multi-cultural Voices: Peer Tutoring and Critical Reflection in the Writing Center." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 20, no. 1, 2010, pp. 40-65.

Pemberton, Michael. "Planning for Hypertexts in the Writing Center...or Not." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 24, no. 1, 2003, pp. 9-24.

Perkins, David N., and Gavriel Salomon. "Teaching for Transfer." Educational Leadership, vol. 46, no. 1, 1988, pp. 22-32.

Perkins, David N., and Gavriel Salomon. "Are Cognitive Skills Context-Bound?" Educational Researcher, vol. 18, no. 1, 1989, pp. 16-25.

Pratt, Mary Louise. "Arts of the Contact Zone." Profession, 1991, pp. 33-40.

Rafoth, Ben, et al. "Sex in the Center: Gender Differences in Tutorial Interactions." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 24, no. 3, 1999, pp. 1-5.

Robertson, Liane, and Kara Taczak. "Teaching or Transfer." Understanding Writing Transfer: Implications for Transformative Student Learning in Higher Education, edited Jessie L. Moore and Randall Bass, Stylus, 2017.

Salomon, Gavriel, and David N. Perkins. "Rocky Roads to Transfer: Rethinking Mechanisms of a Neglected Phenomenon." Educational Psychologist, vol. 24, no. 2, 1989, pp. 113-42.

Sheridan, David M. "All Things to All People: Multiliteracy Consulting and the Materiality of Rhetoric." Multiliteracy Centers: Writing Center Work, New Media, and Multimodal Rhetoric, edited by David M. Sheridan and James A. Inman, Hampton, 2010, pp. 75-107.

Sommers, Nancy, and Laura Saltz. "The Novice as Expert: Writing the Freshman Year." College Composition and Communication, vol. 56, no. 1, 2004, pp. 124-49.

Taczak, Kara, and Liane Robertson. "Reiterative Reflection in the Twenty-First-Century Writing Classroom: An Integrated Approach to Teaching for Transfer." A Rhetoric of Reflection, edited by Kathleen Blake Yancey, UP of Colorado, 2016, pp. 42-63.

Tinberg, Howard. "Reconsidering Transfer Knowledge at the Community College: Challenge and Opportunities." Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 43, no. 1, 2015, pp. 7-31.

Tuomi-Gröhn, Terttu, and Yrjö Engeström. "Conceptualizing Transfer: From Standard Notions to Developmental Perspectives." Between School and Work: New Perspectives on Transfer and Boundary-Crossing, edited by Terttu Tuomi-Gröhn and Yrjö Engeström, Emerald, 2003, pp. 19-38.

Wenger, Etienne. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, 1998.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. Reflection in the Writing Classroom. Utah State UP, 1998.

---. writing.across.contexts, 13 June 2014, writingacrosscontexts.blogspot.com.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, et al. "The Teaching for Transfer Curriculum: The Role of Concurrent Transfer and Inside-and-Outside School Contexts in Supporting Students' Writing Development." College Composition and Communication, vol. 71, no. 2, 2019, pp. 268-95.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, et al. "Writing Across College: Key Terms and Multiple Contexts as Factors Promoting Students' Transfer of Writing Knowledge and Practice." The WAC Journal, vol. 29, 2018, pp. 44-66.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, Liane Robertson, et al. Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. Utah State UP, 2014.

BIOS

Lauren Marshall Bowen is an Assistant Professor of English, Director of Composition, and former Coordinator of the Composition Tutoring Program at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Her work has been published in CCC, College English, Literacy in Composition Studies, and Computers & Composition, among others. Her research interests include writing across the lifespan, age studies, and composition pedagogy.

Matthew Davis is an associate professor of English and the Director of the Center on Media & Society at the University of Massachusetts Boston. He is the current co-editor of Composition Studies and has published or has work forthcoming in CCC, Computers & Composition, enculturation, Kairos, The WAC Journal, and several edited collections.