“There’s Just Something About Her”: The Lasting Influence of Anti-Suffrage Rhetoric on American Voter Attitudes

“There’s Just Something About Her”: The Lasting Influence of Anti-Suffrage Rhetoric on American Voter Attitudes

Peitho Volume 23 Issue 1 Fall 2020

Author(s): Chelsea Bock

Chelsea Bock is an editor and an adjunct communications professor at Anne Arundel Community College. She holds an M.A. in English from the University of Maryland, College Park, and an M.A. in Humanities from Hood College. Her research interests include political rhetoric, public memory, and remediation in media.

Abstract: In this article, I pair my original research with recent data on voter attitudes in America to conclude that sexism among the eligible voting population remains a problem in the 21st century. Additionally, my research suggests that women are more likely than men to exhibit sexist attitudes toward women in politics. This article is timely in a critical election year and significant in its focus on women as participants in their own discrimination.

Tags: 23-1, anti-suffrage rhetoric, citizenship, elections, feminism, suffrage centennial, voter turnoutIn November 2018, Sarah Elfreth made Maryland history as the youngest woman to win an election to the Maryland State Senate at age 30. But like so many other women who work to shatter the glass ceiling, Senator Elfreth ran into her fair share of sexist criticism. “[I was] incessantly criticized for being too young, being unmarried, and being childless. Apparently that combination made me wholly unqualified to serve in the Senate,” she shared during a June 2020 personal interview. “That was the most misogyny I faced in the entire campaign. When women say things like that, it gives men credence to say it” (Elfreth).

Erin Lorenz, a candidate for the Anne Arundel County Board of Education in 2020, shared a similar experience of voters needing to see her as a “traditional” woman. According to Lorenz, voters would ask “But what will you do?” upon learning that she would have to resign from her teaching job if she won. Because many of them looked visibly uncomfortable when she said that she would have to get another job, adding, “I’m getting married in April,” seemed to go over much more smoothly. “They definitely felt more relieved when they knew that,” Lorenz said. Unfortunately, after one hundred years of national suffrage, women like Sarah Elfreth and Erin Lorenz still encounter tired tropes of how women are regarded in the political arena. Women may have the vote, but their fight to be recognized as full political participants is far from over.

The centennial anniversary of women’s suffrage in 2020 gives us many opportunities to celebrate social progress. The new Turning Point Suffrage Memorial in Fairfax County, Virginia is a space for visitors to learn more about the Silent Sentinels, while the Library of Congress crowdfunded archival project, “Suffrage: Women Fight for the Vote,” has provided the public with ways to engage remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic. But while enjoying these commemorations, we must be careful not to succumb to what University of Wisconsin sociologists Matthew Desmond and Mustafa Emirbayer deem the ahistorical fallacy: the belief that past events like the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment “are too far removed to matter to those living in the here-and-now” (Desmond and Emirbayer 344). History is a continuum of connections, and individual instances of progress do not eradicate institutional sexism. There is still so much to learn, and so much to fight for.

My article argues that despite the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920, the rhetoric that charged its opposition still persists when it comes to female voters and female political candidates. To reach this conclusion, I analyze the continuation of anti-suffrage rhetoric over the last century according to the colonial “Republican Mother” archetype, as well as Peter Glick and Susan Fiske’s ambivalent sexism inventory, to establish six appeals of anti-suffrage rhetoric: appeal to respectability politics, appeal to spite, appeal to family, appeal to male structural power, appeal to women as overly emotional, and appeal to unique gender roles. Finally, I share my own recent data from political canvassers on the negative rhetoric surrounding female voters and female candidates, examine the ways in which voters’ comments both echo and diverge from sentiments made one hundred years ago, and establish a seventh rhetorical appeal for the twenty-first century.

Citizenship by Proxy: The Republican Mother

As was the case when black men were legally denied the vote before the passing of the 15th Amendment, definitions of citizenship lay at the heart of the women’s suffrage question. If women did not have the vote, were they full citizens of the United States? And if they were not full citizens, was the goal of the anti-suffrage movement to reserve citizenship, as Elaine Weiss sardonically observes in The Woman’s Hour, “by right of a certain shape of genitalia”? (40)

Rosemarie Zagarri describes the notion of a separate brand of citizenship for women, to be practiced within the boundaries of what is “natural” and therefore appropriate for their sex, as a “broad, long-term, transatlantic reformulation of the role and status of women” in her essay, “Morals, Manners, and the Republican Mother” (Zagarri 193). European philosophers like John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Adam Smith, and Lord Kames lay the groundwork for how Americans eventually conceived of women’s relationship to the family unit and to society more generally. The latter’s assertion that women’s “relationship to their country is secondhand, experienced through husbands and sons,” was particularly influential in the formation of the “Republican Mother” archetype, as it carved out a specific path of political influence that American women could exercise in lieu of suffrage (Kerber 196). In his 1806 essay, “Of the Mode of Education Proper in a Republic,” Benjamin Rush insisted that “[women] should not only be instructed in the usual branches of female education, but they should be taught the principles of liberty and government; the obligations of patriotism should be inculcated upon them” (qtd. in Zagarri 206). By learning about politics in America without any first-hand involvement, women would be able to perform a kind of citizenship by proxy. They could shape the character of men and boys, and by extension, contribute to a more moral society.

Relatedly, the Republican Motherhood ideal is also an illustration of benevolent sexism. Defined by Peter Glick (Lawrence University) and Susan T. Fiske (now Princeton University) in 1996 as one of the two “prongs” of the researchers’ ambivalent sexism inventory, benevolent sexism is the lesser-known cousin of hostile sexism that masquerades as kind and complementary. According to Glick and Fiske, this kind of sexism is comprised of attitudes “[that view] women stereotypically and in restricted roles but that are subjectively positive in feeling tone (for the perceiver) and also tend to elicit behaviors typically categorized as prosocial (e.g. helping) or intimacy-seeking (e.g., self-disclosure)” (Glick and Fiske 492). A contemporary example of benevolently sexist behavior would be a man telling a woman that the catcalls she gets while walking to work are “just compliments,” and that she should “smile more” so as to appear inviting and amicable. Such comments focus on praise while undermining female agency. The woman is harassed, her male friend assures her, because she is just so beautiful, and urges her to sacrifice her comfort to maintain the social order.

For its time, the argument that women should exercise influence over their husbands and sons could be read as progressive and even feminist. But the resulting Republican Mother archetype shaped American conventional wisdom in benevolently sexist ways, and defining women by their sexual and moral purity became grounds for anti-suffrage activists to keep them out of political life. “It was, suffrage opponents explained, because they held women in such high esteem that they denied them the vote,” Christina Wolbrecht and J. Kevin Corder write in A Century of Votes for Women. The authors additionally note that such rhetoric often turned from flattering to frightening once women disobeyed the rules: “An anti-suffrage cartoon presented women with a choice: Reject the right to vote and retain the safety and happiness of the home, or obtain the vote and accept the degradation of the ‘street corner’” (Wolbrecht and Corder 33-34). Left with no middle ground between the home and the street corner, a space that implies poverty, prostitution, and general debasement, women would surely be scared into silence.

The Rhetoric of the Antis: Benevolent Sexism Turns Hostile

The benevolent sexism inherent in the Republican Mother archetype is an example of what Glick and Fiske deem “protective paternalism,” a method of preserving women “as wives, mothers, and romantic objects…to be loved, cherished, and protected” (493). As in the previously mentioned anti-suffrage cartoon, benevolent sexism is often exposed as a cover for hostile sexism once women respond in a way that rebukes the existing social order. The real threat of physical violence that women face while being harassed on the street, for instance, exemplifies how quickly a flatterer can pivot and become an attacker.

It is worth noting that some anti-suffrage rhetoric, usually from individual speakers, did remain benevolently sexist without turning hostile. Many female anti-suffrage activists of the early 20th century revised their former position that women should keep exclusively to the home as more women became active in social clubs and other community organizations. Mrs. J.B. Gilfillan, president of the Minnesota Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, clarified her evolving stance in 1915:

Anti-Suffragists are opposed to women in political life, opposed to women in politics…We believe in women in all the usual phases of public life, except political life. Wherever women’s influence, counsel, or work is needed by the community, there you will find her, so far with little thought of political beliefs…The pedestals they are said to stand upon move them into all the demands of the community. (qtd. in Thurner 40)

Gilfillan subtly frames her position as one that allows women more freedom than they had previously been accustomed to. “We believe in women in all the usual phases of public life” suggests variety of choice as well as eased restrictions, and the words “except political life” may resonate as a fair compromise. Gilfillan’s use of the word “pedestal” is also apt, as pedestals are symbolic of benevolent sexism. Putting women on a metaphorical pedestal first for their “natural” roles as wife and mother, then as a beacon of “political neutrality and nonpartisanship,” is a way of praising them for adhering to boundaries (Thurner 41). To sell the idea further, President Josephine Dodge, the founder and first president of the National Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage, argued that women actually held more power by not being able to vote. She employed respectability politics by urging women to get “the best results from lawmakers by working with them for the common good, not dividing along party lines” (Miller 453). Catharine Beecher pushed women to use “moral persuasion” on male voters instead of voting themselves, another proper way to “create less conflict” (Miller 451). Gilfillan, Dodge and Beecher all used benevolent sexism to persuade by framing less power as more power. By spinning legal limitations as an opportunity for women to realize their unique gifts of “moral persuasion” and “working for the common good,” anti-suffragists were able to frame the absence of the vote as necessary.

The anti-suffrage advertisements found in newspapers and magazines were not so benevolent; in fact, they were quite hostile. Women were forced to choose whether they wanted to be virtuous housewives who left the voting to their husbands or greedy, unsexed barbarians who failed to know their place. The rhetoric in these advertisements performs the dual functions of threatening women who step outside of their proper sphere of influence while playing on men’s fears of losing structural power.

President John Adams’ notion of “petticoat government” influenced many anti-suffrage advertisements, which depicted women as nags, bullies, and literal hens corrupted by their newfound power at the polls (Weiss 29). One cartoon, titled “America When Feminized,” features a hen with a “Votes for Women” sash stepping out of her coop, directing the rooster to “Sit on [the eggs] yourself old man, my country calls ME!” The caption immediately below reads, “The more a politician allows himself to be henpecked the more henpecking we will have in politics,” followed by, “A vote for federal suffrage is a vote for organized female nagging forever” (Weiss). The postcard is certainly meant to horrify its male readers. But because it leans heavily on argumentum ad odium—an appeal to spite—female readers would also be justifiably repulsed at the thought of themselves as hen-like.

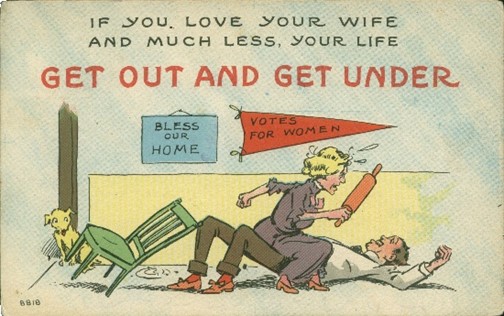

Fig. 1. “Get Out and Get Under.” Palczewski Suffrage Postcard Archive, Feminization of Men Collection.

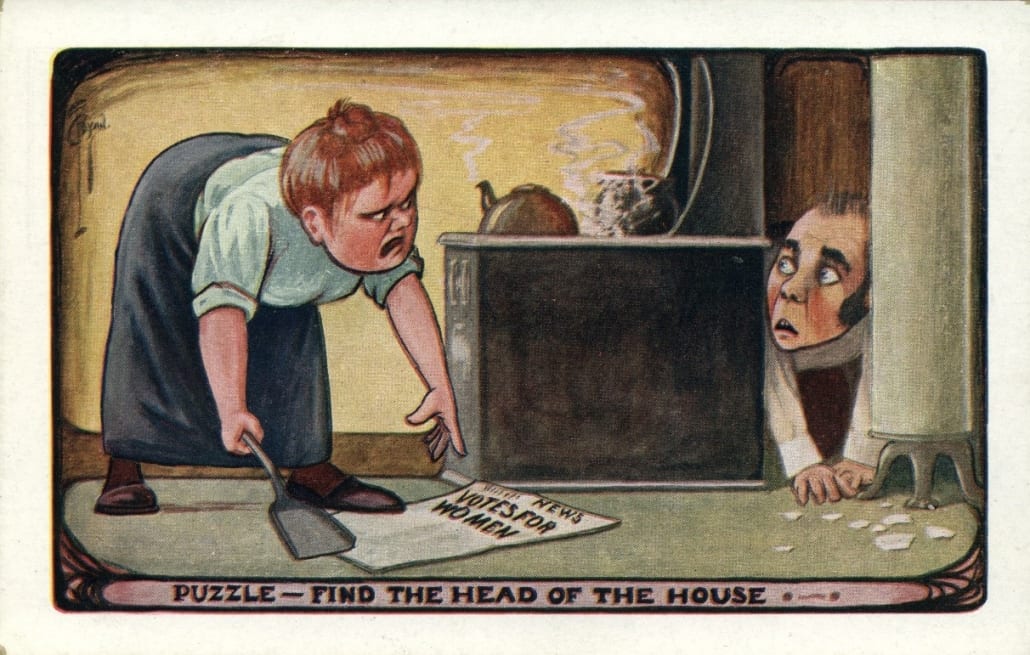

An anti-suffrage postcard from the Catherine H. Palczewski Postcard Archive at the University of Northern Iowa depicts a woman physically dominating her husband and threatening to strike him with a rolling pin (Fig. 1). Here, a traditionally female domestic household item is weaponized to emasculate a man: what was previously a tool of service (providing meals) is now a symbol of tyranny and disorder. On another postcard from the same collection, a woman yells at her husband to clean while pointing urgently to a newspaper with the headline, “Votes for Women” (Figure 2). The husband cowers sheepishly in the corner, and neglected teapots appear to boil over behind him while the caption reads: “Puzzle—Find the Head of the House.” A puzzle, indeed, and a clear appeal to prescribed gender roles. The postcard insists that reversed roles for men and women would be a disaster for the entire household, as the man appears frightened and unable to carry the burden of domestic labor that is, oddly enough, supposed to be enjoyable and fulfilling for his wife.

Fig. 2. “Puzzle – Find the Head of the House.” Palczewski Suffrage Postcard Archive, Feminization of Men Collection.

Hostile sexism in anti-suffrage rhetoric also characterized women as too fragile and unstable to be entrusted with the vote. “Innate physical weakness made white women unfit for the rigors of the electoral competition,” Wolbrecht and Corder explain, “and unable to defend the republic against threats” (34). John Jacob Vertrees, who mentored anti-suffrage activist Josephine Pearson in her fight against Tennessee’s ratification, played on the related stereotype women as innately emotional in his 1916 pamphlet, To the Men of Tennessee on Female Suffrage. He argues in the pamphlet that “a woman’s life is one of frequent and regular periods marked by mental and nervous irritability, when sometimes even her mental equilibrium is disturbed” (qtd. in Weiss 39). Vertrees directly appeals to the idea that women are “too emotional” by citing women’s character flaws, not their positive attributes, as just cause for keeping them out of the voting booth. Anti-suffrage activists also used women’s anger to deem them “too emotional”; in other words, women’s aggressive pursuit of the vote caused their worth to diminish. “When you hand her the ballot, you simply give her a club to knock her brains out,” one Nashville reverend preached. “When she takes the ballot box, you’ve given her a coffin in which to bury the dignities of womanhood” (Weiss 32). The metaphors of violence and death are no accident here. They are a veiled threat, and an eerie foreshadowing of the jailing and torture of suffragist protesters.

By the time the first woman was elected to Congress in 1916—four years before national suffrage—the sexist rhetoric surrounding women in politics was overtly hostile. When Jeannette Rankin of Montana won her seat in the House of Representatives, reporters painted her as “a cheap little actress” prone to “sobbing,” who needed to be “forgive[n] for her election” (Walbert). Rankin’s challenger, Jacob Crull, was so distraught over his loss that he downed a bottle of muriatic acid. But rather than characterize Crull’s action as hysterical, the newspapers published ledes like, “The sting of defeat—administered by a woman.” The message was clear: Jeanette Rankin was responsible because she dared to take a male politician’s place (Walbert). America’s first female representative needed to be punished for stepping out of her natural role, just like the women clamoring for suffrage.

Repurposing Anti-Suffrage Rhetoric for the 20th Century

After the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920, the general expectation in America was for women to show up to the polls in droves. This was not the case. Roughly one third of eligible female voters turned out for the 1920 election compared to almost 70% of their male counterparts. The gender gap continued for some time: although women’s participation surpassed 50% in the 1936 election, men’s participation rose to a record high at about 75% (Wolbrecht and Corder 70-71).

Why the low turnout? Voting was entirely new to women and as a historically oppressed group, they were vulnerable to voter suppression efforts. “Voting is habit forming; turnout in the past increases the probability of turnout in the future,” Wolbrecht and Corder maintain. “Those who have been systemically denied the opportunity to develop the habit due to disenfranchisement are disadvantaged in the future.” Data showing that significantly more women turned out to vote in states without restrictive election laws supports this theory (76-77). For women of color, the road to enfranchisement has been even more fraught. Native American women could not vote until the Indian Citizenship Act was passed in 1924, and Chinese-American women were barred from the vote until 1943, when the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act lifted the ban on Chinese immigration to the United States that had been in effect since 1882. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 deemed racial discrimination unconstitutional after decades of Jim Crow laws that explicitly targeted black voters, though the fight for free and fair elections continues today as gerrymandering, strict voter ID laws, and overt conflicts of interest suppress racial minorities. Women as a demographic continue to be targeted in voter suppression efforts today (“Voter Suppression”). Exact match requirements across multiple documents mean that married, divorced, and transgender women are at risk for being turned away because of name changes. Women in states without early voting will also have less of an opportunity to get to the polls on Election Day, as women still carry the bulk of household labor and childcare (Germano).

Voter attitudes about what was and was not appropriate for women in public life also remained deeply internalized after suffrage. In 1920, 9% of women who participated in a Chicago survey on non-voter behavior stated that they did not “believe” women should vote and/or stated that their husband objected to women voting (Wolbrecht and Corder 78). Little had changed by the time Paul Lazarsfeld, Bernard Berelson, and Hazel Gaudet conducted their research on Eric County, New York voters during the 1940 election. The trio analyzes voting behavior in their 1944 book The People’s Choice: How the Voter Makes Up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign and note that responses from women that trivialized suffrage were not uncommon. Some of these responses included “Voting is for the men,” “I think men should do the voting and the women should stay home and take care of their work,” and “I never will [vote]…a woman’s place is in the home…Leave politics to the men,” signaling a strong adherence to appeals to family and to unique gender roles (Lazarsfeld et al 49). The rhetoric here echoes anti-suffrage sentiment and Republican Motherhood concepts of citizenship. Women who were dismissive of their right to vote held to hard and fast rules about the appropriateness of women in political life. Voting was not only “for” men exclusively; it was unbecoming for a woman who had other “work” to take care of. Though the hostile sexism is apparent here—Keep Out!—it is warranted by benevolently sexist ideas about what a woman is and is not “naturally” suited for. And notably, even though female anti-suffragists in the 1910s advocated for women’s participation in the public sphere so long as this participation was not political, the women quoted in The People’s Choice specifically called for women to remain “in the home” where “their work” was.

Republican Motherhood ideas persisted mid-century, enjoying a revival as what Betty Friedan now famously termed “the problem that has no name” in The Feminine Mystique. However, because women were attending colleges and universities in greater numbers, repurposed anti-suffrage rhetoric found a new audience among graduates. During his 1955 commencement address at Smith College, Adlai Stevenson II urged each woman to “inspire in her home a vision of the meaning of life and freedom,” echoing the citizenship by proxy ideas of the Republican Mother archetype. He also stressed the importance of never letting educational or professional pursuits overshadow domestic duties in an appeal to family. “This assignment for you, as wives and mothers, you can do in the living room with a baby in your lap,” he explained. “I think there is much you can do…in the humble role of housewife. I could wish you no better vocation than that” (qtd. in Friedan 57). In a culture obsessed with adherence to gender roles, where male columnists joked freely that problems could be solved “by taking away women’s right to vote,” Betty Friedan worried that speakers like Adlai Stevenson II would persuade women to normalize the extinguishing of their own voices (11).

Unfortunately, Friedan was more correct than she may have known at the time. During the 1960s and 1970s, women were having less children and becoming parents later in life, pursuing more college degrees, and holding more jobs outside the home. They were also making progress through legislation like the Title IX Education Amendment in 1972 and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 (Wolbrecht and Corder 131, 135). Enter Phyllis Schlafly, who held that “feminism has been a catastrophe for the people it was meant to help,” (qtd. in Storrs 144). A fierce opponent of the proposed Equal Rights Amendment, Schlafly spent much of her recruitment efforts on housewives. Suddenly, an antifeminist activist was encouraging women to use their vote as well as their voice—but only as long as they pledged to undermine women’s equality.

Schlafly frequently appealed to housewives by injecting benevolent sexism into her rhetoric: for instance, by framing opposition to the ERA as a defense of women’s rights rather than an impediment to progress. “The ERA takes away the right of the wife to be supported by her husband,” Schlafly argued on a Good Morning America segment in 1976 where she debated Friedan. She considered her position to be defending “the real rights of women…the right to be in the home as a wife and mother” in the same way that anti-suffrage advocates Gilfillan, Dodge, and Beecher persuaded women that they actually had more power without the vote (“Phyllis Schlafly debates”; Gregorian). She also invoked the hostile sexism of anti-suffrage advertisements by characterizing feminist women as unattractive, hostile, and mannish. “Men should stop treating feminists like ladies,” Schlafly argues in a column entitled “Feminists on the Warpath Get Their Men,” “and instead treat them like the men they say they want to be” (Schlafly).

Fig. 3. Barbara Mikulski and Linda Chavez at the 1986 Maryland Senate Race debate.

Reproduced from J. Scott Applewhite, Associated Press.

This hostile rhetoric was weaponized as female candidates for office became increasingly common in the latter part of the twentieth century. The race in Maryland to fill Charles Mathias’ Senate seat in 1986, for example, came down between Reagan staffer Linda Chavez and Congresswoman Barbara Mikulski (Fig. 3). The former quickly advertised herself to Maryland voters as the right kind of woman for the job: conventionally attractive, calm under all circumstances, and a devoted wife and mother. In short, Chavez performed gender in a “ladylike” way that did not come across as threatening to a male political establishment. Mikulski’s primary campaign had certainly prepared her for sexist attacks from Chavez—both of her Democratic challengers were male and frequently painted themselves as “less dogmatically liberal and less aggressive” than their female counterpart (Sheckels 79). Chavez’s attacks went deeper, focusing on Mikulski’s hiring of a publicly Marxist feminist aide named Teresa Brennan. This “embracing of [a] radical anti-male Marxist feminist such as Brennan,” Chavez claimed at an October 1986 press conference, “was a symbol of what Mikulski had done and would do on Capitol Hill.” Chavez’s mailers, which featured “a grotesquely over-painted pair of very red lips” and read, “Kiss Your Traditional Values Goodbye,” implied that Mikulski’s radical feminist ideas and suspected homosexuality would dismantle traditional notions of male structural power in politics and, by extension, the family (84-85). Furthermore, it echoed the anti-suffrage advertisement idea that feminist women are angling to become men. As Theodore Sheckels writes, Mikulski had to reframe her liberal views and single status in a nurturing way in order to appeal to family and tradition:

In response to the accusation that she was anti-male, Mikulski quipped that her father and nephews and uncles and “the guys down at Bethlehem Steel” would be surprised to hear that. In response to the unvoiced accusation that she was a lesbian, Mikulski jokingly referred to herself as “Aunt Barb” and talked about how, in many families, one daughter became the maiden aunt who took care of the aging parents. She was that maiden aunt, but now she was taking care of not her mom and pop but the voters of the state of Maryland. They were her family; she was their “Aunt Barb.” (Sheckels 85)

Barbara Mikulski’s “Aunt Barb” alter ego successfully refashioned the Republican Mother trope for the late 20th century, appealing to voters with a deeply maternal role meant to overshadow any gossip about sexual orientation. Mikulski could lead the state of Maryland in the Senate while looking after her parents and her surrogate children—Maryland voters—thereby utilizing all of her talents. She smartly leveraged voters’ traditional desire for a nurturing woman in order to make history in a male-dominated arena.

Chavez’s strategy to paint Mikulski as dangerously “anti-male” was effective in more conservative parts of the state like the Eastern Shore and Western Maryland, but ultimately, “Aunt Barb” handily won her election and went on to serve in the United States Senate for thirty years. The combative rhetoric surrounding (and sometimes wielded by) women in politics, however, did not disappear.

How Do Contemporary Voters Feel About Women in Politics?

I spent several months canvassing door-to-door for Senator Elizabeth Warren during her 2020 presidential campaign. The responses from voters were generally positive: male and female voters alike expressed enthusiasm for Warren’s dedication to rebuilding the middle class and fearlessness in spite of Donald Trump’s efforts to bully her. However, enough voters reacted negatively to Warren’s gender that I occasionally felt discouraged. Some voters scoffed at the idea of a female president or suggested that Warren would be better suited “in a supporting role.” Others hovered tentatively, fearing that our country is not ready for this kind of progress.

Reviewing the tenets of Republican Motherhood and past examples of anti-suffrage rhetoric, I wondered about contemporary echoes like those I had encountered in my own travels. I considered that women who ran for office during the 2018 midterm elections had won a record number of congressional seats and that Congress has become substantially more diverse during the tenure of Donald Trump, a president known for his litany of crude and offensive comments about women and people of color (Bialik). The contrast could not be starker. What kinds of rhetoric were canvassers hearing from voters in this environment? And were the women they spoke with emboldened to vote?

First, I sorted the anti-suffrage rhetoric discussed in this paper into six categories that utilized both hostile and benevolent sexism. These categories are as follows:

- Appeal to respectability politics: the notion that women should “go along to get along” as expressed by Josephine Dodge.

- Appeal to family: the notion that a woman’s family must come before any career or political aspirations, as expressed in criticisms of Sarah Elfreth.

- Appeal to women as overly emotional: the notion that men act on rationality while women act on emotion, as expressed in criticisms of Jeannette Rankin.

- Appeal to male structural power: the notion that women in power will emasculate men, as expressed in anti-suffrage postcards where men cower to women.

- Appeal to traditional gender roles: the notion that women have “unique gifts” that justify their belonging to the domestic sphere, as expressed by Catharine Beecher.

- Appeal to spite: the notion that feminist women are “hens,” “angry and mannish,” and other undesirable associations, as expressed in Linda Chavez’s criticism of Barbara Mikulski.

Then, in February 2020, I sent out a brief online survey to eleven female and four male canvassers who had volunteered to share their experiences for the purposes of my research. Every respondent indicated that they have canvassed for female candidates, and the vast majority have canvassed for candidates at multiple levels of government. The female candidates most respondents reported canvassing for were Hillary Clinton for President (8), Elizabeth Warren for President (5), and Sarah Elfreth for Maryland State Senate (8). Others included Barbara Mikulski for Senate and various female candidates for state delegate, mayoral, and county council positions. Though the respondents have mostly covered ground in Maryland, some noted that they have gone door-to-door in other states to include Virginia, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Alabama, Louisiana, Vermont, New Hampshire, Iowa, Indiana, Colorado, and California.

It is important to note that the sample of this survey is small and in no way speaks for larger patterns. I was most interested in not the size of the sample, but in evaluating the fifteen respondents’ qualitative, anecdotal data on the rhetoric that voters currently use when engaged by canvassers. My questions focused on two kinds of rhetoric: voters’ thoughts on the role of women in the electoral process, and voters’ thoughts on women as political candidates.

When canvassers were asked if a male household member ever tried to prevent them from speaking with a female household member while she was home and available, ten out of fifteen answered, “Yes.” The most common behavior from male voters that respondents mentioned was refusing to call a particular female voter to the door even though she was home and on the canvasser’s list. Other behaviors listed included speaking on a female voter’s behalf, preventing an interested female voter from coming to the door, lying about a female voter’s party affiliation (canvassers are equipped with partisan voter registration information), and abruptly interrupting an ongoing conversation between the canvasser and a female voter. “I remember one guy who walked over while I was pleasantly speaking to his wife,” Claire*1 wrote. “[He] gave me the finger and kicked the door shut with his foot.” Respondents noted hearing phrases from hostile male household members that included, “You don’t need to talk to her,” and “Don’t you worry about who she’s voting for.”

Additionally, when the canvassers were asked if “a female voter ever deferred to a male household member in a way that suggests he speaks for her,” eight out of fifteen questionnaire respondents answered, “Yes,” that they picked up on sexist power dynamics while talking to voters. “A woman stated that she wasn’t sure who she was voting for because her husband hadn’t told her yet,” wrote John*. Other explicit comments that respondents noted from female voters included: “I have to consult my husband,” “I vote the way my husband votes,” “It’s a family decision,” and “I’ll have to ask my husband who we’re voting for.” These responses bear an eerie resemblance to the previous selections from Lazarfeld et al’.s The People’s Choice. Though some of the women interviewed for Lazarfeld’s 1940 research advocated for women to abstain from voting altogether, the women quoted here advocated for their own political participation so long as it reinforced their husbands’ views. In both instances women appear to be abiding by respectability politics, playing a supporting role while leaving the ultimate political decisions to men.

Nine out of fifteen survey respondents indicated that they heard overtly sexist rhetoric from male voters while discussing female candidates. The criticisms that respondents shared included: “Women are too emotional,” “She’s just not likable,” “There’s just something about her,” “America isn’t ready for a woman,” “What happens if she’s on her period?” “She’s too inexperienced” (often said about female candidates who had objectively more experience than their male counterparts), “She’s not attractive,” “Other countries won’t respect us if we have a female leader,” and “Women are caring by nature—could a woman really command the armed forces?”—the latter two comments being direct appeals to women as “too emotional” and better suited for more nurturing environments. Respondents cited electability as a common concern among voters, e.g. “I don’t think a woman can win.” One of the respondents, Nathan*, campaigned all over the country for Kamala Harris during her presidential candidacy. “Men seem to be more cagey about copping to sexist attitudes when approached on the doors,” he said. “I approached a voter about Kamala Harris who explicitly said that the senator wouldn’t be ready to lead the armed forces because of her gender. I pointed out that Harris had previously run California’s Department of Justice—a police force larger than most nations’ military forces—and although he didn’t have a counter-argument, he held to his views that a woman just wouldn’t be capable.”

The argument that a woman cannot handle being in charge of the United States military was notably reported by multiple canvassers. This comment is a clear appeal to male structural power, as the military has strong masculine connotations. Most of the overtly sexist comments (such as regarding women not being able to command the military and women getting “irrational” because of their periods) were reported by male canvassers, which could suggest that men with sexist attitudes feel more comfortable relaying such comments to other men.

While nine survey respondents shared that they had heard sexist rhetoric from male voters, eleven stated that they had heard sexist rhetoric from female voters. Deborah* shared that in her personal experience, “This seems to happen more frequently than men, to be frank.” Some of the comments from female voters mirrored those of male voters, namely, “America isn’t ready,” “She’s inexperienced,” and “A woman can’t win.” Rachel* observed that among female voters there were “still worries that a woman couldn’t win the seat, but from a place of worry more than a place of defensiveness as men usually do.” But many other remarks from women were overtly hostile. According to the canvassers, several female voters stated explicitly that they “just don’t like female candidates.” Paula* shared that female voters often criticized a particular female candidate’s “attractiveness, voice, friendliness, attitude” and that some went so far as to call the candidate a “bitch” in an appeal to spite. Nathan called instances of internalized sexism at the doors “beyond depressing,” writing, “statements like, ‘A woman just shouldn’t be president’ have come up from women several times.”

A New Kind of Sexist Rhetoric in Politics

Even though their stories of sexism were thankfully not representative of the majority of doors they knocked, the small pool of canvassers surveyed shared enough rhetoric to indicate that gender-based discrimination and internalized sexism are still prominent issues. Furthermore, the appeals of this rhetoric aligned strongly with the tenets of anti-suffrage rhetoric. “I’ve had men and women ask how my husband and children felt about me running for office,” Paula wrote on what it was like to canvass for her own campaign. “I found most men MORE supportive than other women…one woman even asked if it was fair to my pets.” Like Barbara Mikulski, Sarah Elfreth, and Erin Lorenz, Paula was criticized by voters for not seeming “family-oriented” enough, or for not appearing to prioritize her family over her political aims.

Much of the rhetoric that respondents shared was a modern reworking of anti-suffrage or post-World War II ideas about women’s roles. The criticisms directed at Paula for campaigning while female echo Landon R.Y. Storrs’ analysis of sexist rhetoric during the second red scare, when married mothers who pursued careers and other passions were accused of “selfishly indulging material desires or unwomanly ambitions”—a direct appeal to tradition and family (Storrs 135). “I’ll have to ask my husband who we’re voting for,” is a startling example of women erasing their own voices in the political sphere and similarly, “I vote the way my husband votes,” gestures at an effort to maintain a gendered status quo. This rhetoric also suggests a household sexism that makes its way into the polls. If the husband controls the “family vote,” the family vote will probably not be going to female candidates.

Instances of benevolent and hostile sexism reported by the canvassers were not associated with one gender or another. Men and women are capable of being benevolent and hostile, albeit in their own ways: while men were more likely to project their hostility onto the canvasser (slamming the door; giving the finger), women called female candidates derogatory names, criticized their superficial elements like attractiveness and voice, and made blanket statements about “not liking” female candidates in general. These instances of women tearing each other down, difficult as they are to read, are part of a longstanding tradition in America to drive women away from positions of power. “Female officials faced a nearly irresoluble double bind,” Storrs writes about sexist attitudes in the middle of the 20th century, “because normative constructions of femininity were incompatible with the wielding of power and expertise” (Storrs 142). Glick and Fiske’s 2011 update to their original work, entitled “Ambivalent Sexism Revisited,” similarly enforces the idea that benevolent sexism (abbreviated below as “BS”) and hostile sexism (abbreviated below as “HS”) are two sides of the same coin, upholding a system of reward and punishment for women:

Ambivalent sexists were not “mentally conflicted,” rather, their subjectively positive and negative attitudes reflected complementary and mutually reinforcing ideologies…at least as ancient as polarized stereotypes of the Madonna and Mary Magdalene. BS was the carrot aimed at enticing women to enact traditional roles and HS was the stick used to punish them when they resisted. One emphasizes reward and the other emphasizes punishment (hence their differing valences) but both work toward a common aim: maintaining a gender-traditional status quo. (532)

If the hostile sexism of today looks relatively similar to that of the past, what about benevolent sexism? It persists, certainly. But it looks quite different from the way anti-suffrage activists appeared to glorify women, urging them to use their unique and special talents to explore avenues other than politics. Now, benevolent sexism looks a lot like fear and deflection. “America isn’t ready,” voters say. “What if a woman can’t win?” Rhetoric like this suggests that even though voters would be personally comfortable with a female president, they hesitate because the rest of the country may not feel the same way. The Atlantic’s Moira Donegan calls these attitudes “sexism by proxy,” or “voter masochism disguised as pragmatism” (Donegan). By basing their decisions on what they suspect others will do, voters create a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Anti-suffrage rhetoric has certainly found new life in the one hundred years since national suffrage became the law of the land, and is enjoying a revival during the Trump presidency. The 2020 Republican National Convention featured speaker Abby Johnson, a former Planned Parenthood employee turned pro-life activist who tweeted in May 2020 that she “would support bringing back household voting.” When asked to clarify, Johnson responded that “[i]n a Godly household, the husband would have the final say” (@AbbyJohnson). Just as Phyllis Schlafly endorsed Donald Trump in 2016, women like Abby Johnson continue to uphold the patriarchal status quo in the interest of “Making America Great Again.” But while appeals to male structural power are continually reintroduced to mainstream America, a new appeal has emerged that could be called an “appeal to pragmatism.” When voters declare that “a woman can’t win” the presidency or that “America isn’t ready” for female leadership, they are doing their best to sound rational and impartial. “I’m not sexist,” they argue, “but my neighbor is.” Or more broadly and abstractly: “America is sexist.” The appeal to pragmatism continues in the tradition of undermining women, but unlike other more brash appeals, it is insidiously self-defeating. The only way to curb it, along with other sexist fallacies, is to identify them as such and work toward citizenship for women in the fullest sense of the word.

Endnote

- * indicates a pseudonym.

Appendix A: Survey Protocol

February 2020 via Typeform.com

- Question 1: What kinds of political campaigns have you canvassed for? (Check all that apply.)

- Federal

- State

- County

- Municipal

- Question 2: In what areas have you canvassed? (List as many states, counties, and municipalities as apply.)

- Question 3: In your experience canvassing door to door, has a male member of the household ever tried to prevent you from speaking with a female member of the household while she is home/available?

- Question 4: In your experience canvassing door to door, has a female household member ever stated that a male household member does not want her to vote or has tried to prevent her from getting to the polls?

- Question 5: In your experience canvassing door to door, has a female voter ever deferred to a male household member in a way that suggests he speaks for her? (e.g. “My husband makes those decisions,” “I’ll have to ask my husband,” etc.)

- Question 6: Have you ever canvassed for any female candidates?

- Question 7: Have you had any experiences with male voters expressing overtly sexist feelings about a particular female candidate or female candidates in general?

- Question 8: Have you had any experiences with female voters expressing overtly sexist feelings about a particular female candidate or female candidates in general?

- Question 9: Have you had any experiences with male voters reacting POSITIVELY to female candidates in general/more female representation in government?

Works Cited

- @AbbyJohnson. “Here’s another one. I would support bringing back household voting. How anti-feminist of me.” Twitter, 2 May 2020, 11:21 a.m. Accessed 10 Sept. 2020.

- @AbbyJohnson. “Then they would have to decide on one vote. In a Godly household, the husband would get the final say.” Twitter, 2 May 2020, 11:37 a.m. Accessed 10 Sept. 2020.

- Applewhite, J. Scott. “Mikulski (left) and her then-opponent Linda Chavez hold hands before the Maryland Senate candidates debate in 1986.” NPR, Brian Naylor, 2 Mar. 2015. Accessed 5 Sept. 2020.

- Bialik, Kristen. “For the fifth time in a row, the new Congress is the most racially and ethnically diverse ever.” Pew Research Center, 8 Feb. 2019. Accessed 7 Sept. 2020.

- Bock, Chelsea. “Research Paper: Sexism Among Voters.” Typeform.com, 23 Feb. 2020. Survey.

- Desmond, Matthew, and Mustafa Emirbayer. “What is Racial Domination?” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, vol. 6, 2009, pp. 335-355. Accessed 20 Mar. 2020.

- Donegan, Moira. “Elizabeth Warren’s Radical Idea.” The Atlantic, 26 August 2019. Accessed 20 Mar. 2020.

- Elfreth, Sarah. Personal Interview. 15 June 2020.

- Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1963.

- Germano, Maggie. “Women are Working More Than Ever, But They Still Take On Most Household Responsibilities.” Forbes, 27 Mar. 2019. Accessed 12 June 2020.

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. “The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 70, no. 3, 1996, pp. 491-512. APA PsychNet. Accessed 20 Mar. 2020.

- — “Ambivalent Sexism Revisited.” Psychology of Women Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 3, 2011, pp. 530-535. Sage Publications. Accessed 14 Apr. 2020.

- Gregorian, Dareh. “The Equal Rights Amendment could soon hit a major milestone. It may be 40 years too late.” NBCNews, 11 Jan. 2020. Accessed 14 June 2020.

- Kerber, Linda. “The Republican Mother: Women and the Enlightenment—An American Perspective.” American Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 2, Summer 1976, pp. 187-205. Accessed 20 Mar. 2020.

- Lazarsfeld, Paul Felix et al. The People’s Choice: How the Voter Makes Up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign. Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1944.

- Lorenz, Erin. Personal Interview. 12 June 2020.

- Miller, Joe C. “Never a Fight of Woman Against Man: What Textbooks Don’t Say About Women’s Suffrage.” History Teacher, vol. 48, no. 3, May 2015, pp. 437-482. Accessed 20 Mar. 2020.

- “Phyllis Schlafly debates Betty Friedan on ERA.” YouTube, uploaded by Phyllis Schlafly Eagles, 10 Jan. 2018. Accessed 15 June 2020.

- Palczewski, Catherine H. Postcard Archive. University of Northern Iowa. Cedar Falls, IA.

- Schlafly, Phyllis. “Feminists on the Warpath Get Their Men.” Eagle Forum, 16 Feb. 2005. Accessed 15 June 2020.

- Sheckels, Theodore F. Maryland Politics and Political Communication, 1950—2005. Lexington Books, 2006.

- Storrs, Landon R.Y. “Attacking the Washington ‘Femmocracy’: Antifeminism in the Cold War Campaign against ‘Communists in Government.’” Feminist Studies, vol. 33, no. 1, Spring 2007, pp. 118-152. Accessed 24 Mar. 2020.

- Thurner, Manuela. “Better Citizens Without the Ballot: American AntiSuffrage Women and Their Rationale During the Progressive Era.” Journal of Women’s History, vol. 5, no. 1, Spring 1993, pp. 33-60. Accessed 24 Mar. 2020.

- “Voter Suppression Targets Women, Youth and Communities of Color (Issue Advisory, Part One).” National Organization for Women, August 2014. Accessed 12 June 2020.

- Walbert, Kate. “Has Anything Changed For Female Politicians?” The New Yorker, 16 August 2016. Accessed 4 Dec. 2019.

- Weiss, Elaine. The Woman’s Hour. Penguin Books, 2018.

- Wolbrecht, Christina and J. Kevin Corder. A Century of Votes for Women. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Zagarri, Rosemarie. “Morals, Manners, and the Republican Mother.” American Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 2, June 1992, pp. 192-215. Accessed 12 June 2020.