Religious Limitations, Mislabeling, and Positions of Authority: A Rhetorical Case for Beth Moore

Religious Limitations, Mislabeling, and Positions of Authority: A Rhetorical Case for Beth Moore

Peitho Volume 25 Issue 2, Winter 2023

Author(s): Samantha Rae-Garvey

Samantha Rae-Garvey earned her MA in Rhetoric and Composition from Georgia State University in 2022. Her research focuses on the intersections of literacy studies, feminist methodology, and community-engaged pedagogy with particular interest in religious activism. Rae-Garvey’s master’s thesis utilized Beth Moore’s departure from the Southern Baptist Convention as a demonstration of identity enacted through a certain agent (faith) in both narrative and shared space.

Abstract: This essay explores key rhetorical acts of prominent evangelical author, speaker, and teacher, Beth Moore. By utilizing Tweets posted by Moore in response to controversies within the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) as well as her eventual decision to leave the SBC, this essay focuses on the ways in which religious women leaders assert their Biblical positions of authority in our current moment. As such, this essay defines and illustrates both the persistent and the unique challenges--including religious limitations and mislabeling--that 21st century religious women encounter. The aim of this essay, then, is to invite scholars to consider Moore’s role as a rhetor and living pioneer of women's ministry in order to expand our trajectory of research and better include the ways in which today's religious women leaders like Moore pursue Biblical equality and authority within the church.

Tags: authority, faith, feminism, limitations, ministry, mislabeling, religionAs the first woman to partner and publish with Lifeway Christian Resources, a Southern Baptist media production company [1], Beth Moore has become a cornerstone of women’s ministry. Garnering international success, Moore has authored nine books and over 20 Bible studies that have been translated in more than 20 languages. Additionally, both Living Proof Ministries’ (Moore’s official ministry trademark) annual “Living Proof Live” events and Moore’s Twitter account with one million plus followers have likewise reached audiences worldwide. This success across multiple mediums and platforms has built Moore’s authority as a mainstream religious figure. Most importantly, this success has come in spite of limitations to her right to teach in Biblical contexts.

While her work has proven ubiquitous across many religious denominations, Moore remained a faithful member of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC)—a denomination that does not acknowledge or endorse women in pastoral roles—for over 40 years. During this time Moore consistently rejected the title of “pastor,” in accordance with SBC policies that reserve ministerial and pastoral roles to men. Still, her position as a prominent evangelical figure gave her a particular authority to speak out in moments of necessity. Her departure from the SBC in March of 2021 is one such moment.

Moore’s influence within the Christian sphere establishes her as a dynamic figure in religious rhetoric, in part, because of these limitations imposed on her religious authority. In this way Moore’s success presents an opportunity to recognize that the women’s fight for religious authority is not strictly an 18th and 19th century issue, which has been explored by scholars like Roxanne Mountford (The Gendered Pulpit). Rather, this issue of contesting women’s roles in the church is alive and active in one the largest and most prominent 21st century Christian denominations. In this way, scholars like Stephanie Martin, and T.J. Geiger have published articles featuring Beth Moore, specifically, and her role in raising the issue of sexual abuse, exploitation, and women’s rights to speak out within religious settings. Still, there are more contexts in which to understand Moore’s impact and influence within the evangelical sphere.

Moore’s official Twitter account is the gateway into bringing feminist scholarship of 18th and 19th century religious women into our current moment. Thus, this essay invites an interdisciplinary audience of feminist scholars to consider Moore’s role as a rhetor and living pioneer of women’s ministry to further expose the ongoing challenges of evangelical women who at once adhere to and challenge limitations to their authority to speak out against abuse within religious settings by looking at key posts from Moore’s Twitter account. Ultimately, this essay argues that Moore’s marriage to and divorce from the SBC provides a new critical lens by which we should explore this role.

The Authority to Speak: Beth Moore’s Place in Feminist Scholarship

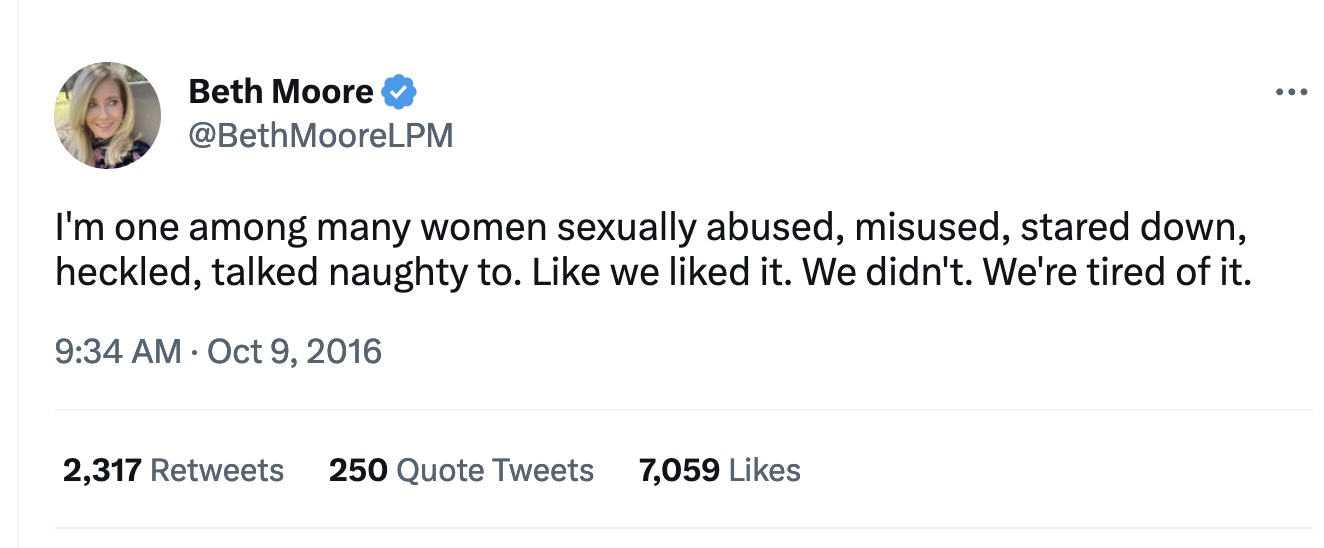

Throughout her near thirty-year career, Moore has been a leading contemporary representation of the trajectory by which evangelical women pursue the Christian life. Still, her history with the SBC is complicated. Moore worked to develop and lead the rise of women’s Bible studies throughout the 1980s and 1990s to date. Speaking candidly, in early 2020 during an episode of Ainsley’s Bible Study on Fox and Friends about her own experience, Moore stated simply that she “fell victim to a childhood sexual abuse within [her] own home” (“Beth Moore Says”). So, Moore’s opposition to Donald Trump as the SBC’s choice conservative presidential candidate because of his disrespect toward women sparked her proactivity against sexual abuse. For Moore, the leaked audio of Trump’s “locker room talk” [2] should have been grounds to disqualify him from holding office. In a 2016 Twitter thread, part of which is seen in Figure 1 below, Moore summed up her distress by ending quite simply, “We’re tired of it.” (@BethMooreLPM 2016).

Figure 1: Beth Moore Tweet from October 9, 2016 Twitter thread in response to evangelical support of Donald Trump following leaked audio of his “locker room talk.” Text: “I’m one among many women sexually abused, misused, stared down, heckled, talked naughty to. Like we liked it. We didn’t. We’re tired of it.”

This Twitter thread was not intended as an endorsement for any opposing candidate during that election. Rather, the rhetorical action here is what Stephanie Martin in “Resisting a Rhetoric of Active Passivism” defines as an enactment of evangelical citizenship that promotes women to at once “believe in Jesus and also agitate as agents of change against patriarchy, misogyny, sexism, and a long-entrenched evangelical posture that encouraged—even praised— female silence” (321). Indeed, the predominant issue surrounding Moore’s opposition to Trump was whether or not she had the authority to speak at all.

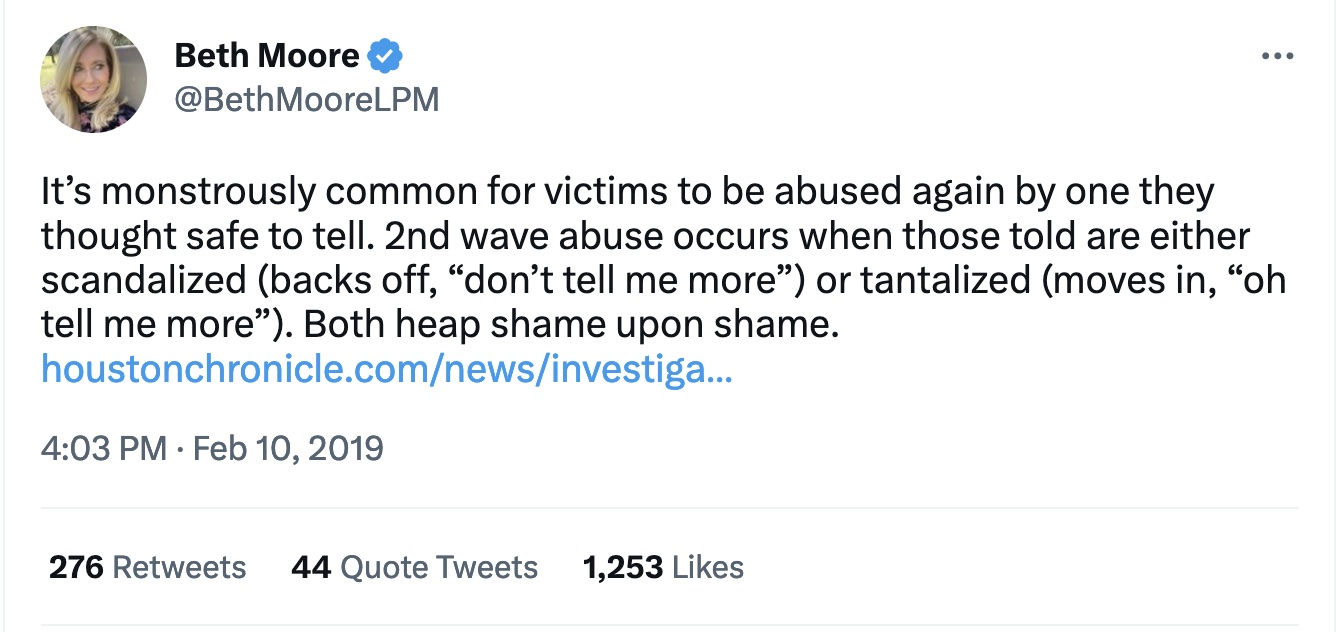

Throughout a series of Tweets and blog posts over the next few years, Moore continued to go up against the “misogyny, objectification and astonishing disesteem of women” that she felt was manifesting through the SBC’s support of Trump (Moore “A Letter”). In February of 2019, an “Abuse of Faith” report released by the Houston Chronicle and San Antonia Express news detailed an investigation into sexual abuse and misconduct among SBC pastors, leaders, and prominent members. “2nd wave abuse occurs when those told are either scandalized (backs off, “don’t tell me more”) or tantalized (moves in, “oh tell me more”),” Moore wrote in a responding Tweet on February 10, 2019 (@BethMooreLPM). As T.J. Geiger in “Forgiveness is More than Platitudes […],” Moore’s point was to “urge [the SBC] to move away from platitude-based forgiveness” if the SBC as a whole would ever uphold their own standards of tradition and doctrine (166). For Moore, this tradition and doctrine is null and void when women of the SBC are marginalized.

Figure 2: Moore’s Tweet from February 10, 2019, which is her response to the Abuse of Faith report from the Houston Chronicle. The article is linked in her Tweet. Text: “It’s monstrously common for victims to be abused again by one they thought safe to tell. 2nd wave abuse occurs when those told are either scandalized (backs off, ‘don’t tell me more’) or tantalized (moves in, ‘oh tell me more’). Both heap shame upon shame.”

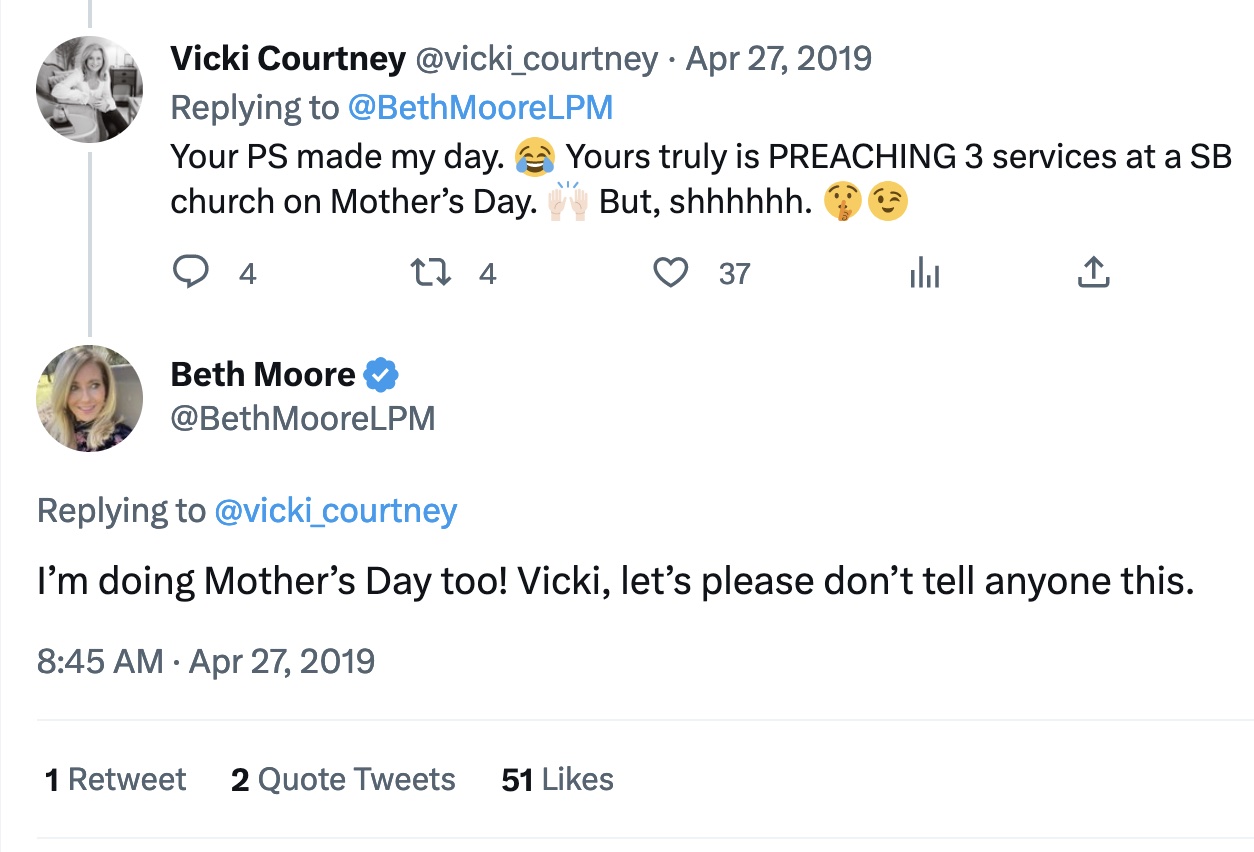

Important to note here is that though she has consistently rejected the title of preacher, Moore’s critics, particularly those within the SBC, label her as such any time she speaks publicly. The intention behind this mislabeling, and Moore’s understanding of it becomes an interesting point for further study. One example, Figure 3 below, is a Tweet from 2019, which Moore posted in response to fellow Christian author Vicki Courtney. Courtney tells Moore that she would be preaching for Mother’s Day, to which Moore responds that she was “doing Mother’s Day too” but that they shouldn’t “tell anyone this” (@BethMooreLPM May 2019). That both women play on the idea that these preaching engagements should be kept secret illustrate the aspect of rhetorical silencing that the aforementioned mislabeling embodies.

Figure 3: Christian author Vicki Courtney responds to a Moore Tweet by acknowledging she will be preaching three service at her Southern Baptist (SB) church. It is clear that both women play on the idea that their preaching engagements should be kept secret. Text: Vicki Courtney: “Your PS made my day. (crying-laughing emoji) Yours truly is PREACHING 3 services at a SB church on Mother’s Day. (raising hands emoji) But, shhhhhh. (shushing face emoji) (winking face emoji).” Beth Moore: “I’m doing Mother’s Day too! Vicki, let’s please don’t tell anyone this.”

Citing the marginalization of its women as one a key factor, Moore announced her separation from the SBC in April of 2021. This decision to leave the SBC is a rhetorical act that demonstrates Moore’s understanding and utilization of her own authority to speak, or what Martin terms as “renegotiating [her] citizenship” within the confinements of necessity (317). Again, what becomes most interesting when we argue for Moore’s importance as a feminist figure to study is that her career has been built on an ideal of renegotiation.

Becoming Beth Moore: Teaching, Writing, and the Rhetoric of a Ministry

As mentioned, Moore capitalized on the available means of reaching her intended audience through teaching women’s aerobics classes and speaking at women’s luncheons. She self-published her first book Things Pondered in 1993 and went on to become the first woman to publish a Bible study for Lifeway Christian Resources. Though this near thirty-year partnership ended after Moore’s separation from the SBC in 2021, her work still lines the shelves in every Lifeway store, alongside the work of other prominent Christian women like Priscilla Shirer, Lysa TerKeurst, and Jennie Allen.

To illustrate her messages Moore pulls in examples of her own unique life experiences, which includes building a career while attending to motherhood, homemaking, and keeping up appearances. In this way, women from multiple denominations can easily situate themselves within the context of what she is teaching. Today, as Kate Bowler explains in The Preacher’s Wife: The Precarious Power of Evangelical Women Celebrities, “with over 11 million of her products sold, Beth’s name has become synonymous with women’s Bible studies” (23).

In 1994 Moore founded Living Proof Ministries (LPM), an organization “dedicated to [encouraging] people to come to know and love Jesus Christ through the study of Scripture” (“About Beth”). Through LPM, Moore has headlined and hosted Living Proof Live events that have reached 22 million women worldwide. In 2008, the first simulcast of one of these events reached “70,000 people meeting in 715 places” at once (Baptist Press). “Moore’s success,” Emma Green wrote in a 2018 article for The Atlantic, “was possible because she spent her career carefully mapping the boundaries of acceptability for female evangelical leaders.” These boundaries have kept Moore within the ideals of the faith that ultimately helped her to create her own authority as an evangelical woman who has been called to reach other women through Biblical study. These boundaries, likewise, accommodate her various rhetorical activities and the ways in which she both understands, pursues, and renegotiates her religious position and authority.

Confronting the Limitations of Beth Moore

I’m not looking to take a man’s place…

I’m just looking for my place.

–Beth Moore, Living Proof Live, Norfolk, VA. 2016

From humble beginnings as a Biblical aerobics choreographer to amassing various speaking invitations, Moore rose to fame by following her calling: teaching scripture to women. Understanding her own authority in this way exposes the positionality of both her subject matter as well as her citizenship within the evangelical community. Sensitivity to the moment manifests in Moore’s proactivity against the silencing of women in religious contexts. We know that Moore’s rejection of the SBC’s embracing of Donald Trump stemmed from personal experiences of sexual abuse. She saw this embracing combined with other rising allegations in 2016 of sexual abuse with the SBC as a “tolerance for leaders who treated women with disrespect” (“Bible Teacher Beth Moore”). In other words, the marginalization of SBC women was simply not important to leaders on the grand scale. As T.J. Geiger in “Forsaking Proverbs of Ashes” points out, Moore “mobilized a costly rhetorical grace that encouraged spiritually grounded shifts in perception” (324). Summarized succinctly, Geiger clarifies that the difference between “cheap grace” and “costly grace” lies within the application of accountability (“Forsaking” 320). While opposition to Moore’s authority to teach and ultimately speak out from leaders in the SBC operates under a concern of modifying tradition and doctrine, this idea of rhetorical grace allows us to apply a more critical lens.

On May 22, 2022, a year after Moore announced her separation, “a previously secret list of hundreds of pastors and other church-affiliated personnel accused of sexual abuse” within the SBC was released to the public (The Associated Press). Moore quickly responded. A Twitter thread (Figure 4) from May 23, 2022, shows her frustration. The last Tweet in this thread sums up her main speaking points: “It’s too late to make it right with me. It is not too late to make it right with [SBC women]” (@BethMooreLPM May 2022).

![Figure 4: Moore’s Twitter thread the day after news broke of the investigative report concerning the list of SBC pastors and leaders accused of sexual misconduct and abuse. Text: (first tweet) “If you still refuse to believe facts stacked Himalayan high before your eyes and insist the independent group hired to conduct the investigation is part of a (liberal!) human conspiracy or demonic attack, you’re not just deceived. You are part of the deception. If you can go on” (second tweet) “your merry way in your SBC organization and carry on like nothing happened and like none of this convention rot concerns you, it will not have been “they” who decayed a denomination. It will have been you. With this I will do my best to close my mouth in regard to the SBC:” (third tweet) “If you can dismiss or explain away this investigative report or do the bare minimum for the sake of appearances, still denying that your men’s club mentality was in any way complicit, my head covering’s off to you. Lottie Moon’s tiny little body is rolling over in her grave.” (fourth tweet) “I loved you. You have betrayed your women. It’s too late to make it right with me. It is not too late to make it right with them.” [Editor’s Note: Lottie Moon was a prominent Southern Baptist missionary who is remembered in the Southern Baptist Convention; each year congregations collect a Lottie Moon Offering to benefit missionary work.]](/docs/peitho/files/2023/03/Rae-GarveyFigure4.jpg)

Figure 4: Moore’s Twitter thread the day after news broke of the investigative report concerning the list of SBC pastors and leaders accused of sexual misconduct and abuse. Text: (first tweet) “If you still refuse to believe facts stacked Himalayan high before your eyes and insist the independent group hired to conduct the investigation is part of a (liberal!) human conspiracy or demonic attack, you’re not just deceived. You are part of the deception. If you can go on” (second tweet) “your merry way in your SBC organization and carry on like nothing happened and like none of this convention rot concerns you, it will not have been “they” who decayed a denomination. It will have been you. With this I will do my best to close my mouth in regard to the SBC:” (third tweet) “If you can dismiss or explain away this investigative report or do the bare minimum for the sake of appearances, still denying that your men’s club mentality was in any way complicit, my head covering’s off to you. Lottie Moon’s tiny little body is rolling over in her grave.” (fourth tweet) “I loved you. You have betrayed your women. It’s too late to make it right with me. It is not too late to make it right with them.” [Editor’s Note: Lottie Moon was a prominent Southern Baptist missionary who is remembered in the Southern Baptist Convention; each year congregations collect a Lottie Moon Offering to benefit missionary work.]

Moore as an Inspiration for the Future of Religious Feminist Study

It is interesting to consider the ways Moore’s complicated membership in the SBC provides a certain platform on which she establishes her religious authority, particularly as she enacts this authority through her Twitter account. Here, we move beyond the limitations of evangelical women to focus on how those limitations have been used as rhetorical tools in the fight against the sexualization and marginalization of women in religious settings. That is to say that particular aspects of one’s identity remain the same regardless of the circumstances. This is especially evident as we consider an identity that is based on religious faith. It is this religious faith that allows the individual to determine appropriate authority which ultimately depends on a willingness to analyze both the self and the situation. Again, Martin’s idea of renegotiation and Geiger’s point of rhetorical grace become key. Still, we are left wondering where exactly Moore fits not only in terms of her authority to speak but also in her right to be heard.

Regarding the previous point, Charlotte Hogg offers some valuable insight. In “Including Conservative Women’s Rhetorics in an ‘Ethics of Hope of Care,’” Hogg utilizes the framework of Royster and Kirsch’s “ethics of hope and care” to situate two “parameters that feminist scholars are comfortable with: radical and sophisticated” (392). Explicit and direct challenges to patriarchal and antifeminist systems usually constitute what defines a feminist. Traditionally, and presumptively, these parameters have been attached only to women who have challenged oppression in ways that place them comfortably within particular standards of feminism. Hogg clarifies in the article “What’s (Not) in a Name”: “As the sense of audience shifts for each rhetorical situation, tracing a discernable trend with regard to our nomenclature proves somewhat elusive, though faint patterns do appear” (194). Trends in this way refer to basic understandings; or, to relate back to the first Hogg’s reference, the two parameters most comfortable for feminist scholarship.

Moore’s departure from the SBC is evidence that adherence to particular Biblical traditions and customs do not exclude today’s conservative evangelical women from dynamic conversations in feminist rhetorics. Perhaps, then, Moore serves as a catalyst for elevating research on 21st century women who achieve mega influence in spite of imposed limitations to their religious authority by the denominations with which they identify; such influence that separating their name from that particular denomination becomes mainstream news. Following the work of Geiger, Hogg, and Martin, we can seek to expand our focus to acknowledge and amplify Beth Moore’s separation from the SBC as a key rhetorical act in the fight against the abuse and marginalization of 21st century religious women. Some questions to ponder, then, are: In what ways did the SBC’s mislabeling of Beth Moore’s role serve to establish her religious authority? With an eye on Moore’s use of Twitter, to what extent does this mislabeling help us to understand Geiger’s idea of rhetorical grace and Martin’s point of renegotiation? Lastly, how does the specific case of Moore’s departure from the SBC help us to better understand mislabeling and limitations to authority?

Works Cited

@BethMooreLPM. “I am one of many…” Twitter, 9 October 2016. twitter.com/BethMooreLPM/status/785126388776873985

@BethMooreLPM. “It’s monstrously common for victims…” Twitter, 10 February 2019. twitter.com/BethMooreLPM/status/1094718474461605893

@BethMooreLPM. “I’m doing Mother’s Day too! Vicki, let’s please don’t tell anyone this.” Twitter, 27 April 2019. twitter.com/bethmoorelpm/status/1122134785244184576?lang=en

@BethMooreLPM. “I loved you…” Twitter, 23 May 2022. twitter.com/BethMooreLPM/status/1528741088642596864

About Lifeway, 2023, www.lifeway.com/en/about.

“About Beth.” Living Proof Ministries, 2021, www.lproof.org/about

“Abuse of Faith.” Houston Chronicle, www.houstonchronicle.com/news/investigations/abuse-of-faith/.

“Beth Moore Simulcast Reaches 70,000 -.” Baptist Press, web.archive.org/web/20110609033935/www.bpnews.net/BPnews.asp?ID=28704.

“Beth Moore Says Memorizing Scripture Helped Her to Heal from Sexual Abuse.” Christianity Today, March 2, 2020. www.christiantoday.com/article/beth-mooresays-memorising-scripture-helped-her-to-heal-from-sexual-abuse/134342.htm.

Bowler, Kate. The Preacher’s Wife: The Precarious Power of Evangelical Women Celebrities. Princeton University Press, 2019.

“Events.” Living Proof Ministries, 2022, https://www.lproof.org/events

Fahrenthold, David A. “Trump Recorded Having Extremely Lewd Conversation about Women in 2005.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 8 Oct. 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-recorded-having-extremely-lewdconversation-about-women-in-2005/2016/10/07/3b9ce776-8cb4-11e6-bf8a3d26847eeed4_story.html.

Geiger, T.J. “Forsaking Proverbs of Ashes: Evangelical Women, Donald Trump, and Rhetorical Grace.” Peitho, vol. 20.2, 2018, pp. 315-337.

Geiger, T.J. “Forgiveness is More than Platitudes: Evangelical Women, Sexual Violence, and Casuistic Tightening.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 2, 2019, pp. 163-184.

Green, E. (2021, May 17). “The Tiny Blond Bible Teacher Taking on the Evangelical Political Machine.” The Atlantic. theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/10/beth-moore-bible-study/568288/

Hogg, Charlotte. “Including Conservative Women’s Rhetorics in an ‘Ethics of Hope and Care.’” Rhetoric Review vol. 34 no. 4. 2015: 391-408.

Hogg, Charlotte. “What’s (Not) in a Name: Considerations and Consequences of the Field’s Nomenclature.” Peitho, vol. 19, no. 2, 2017. cfshrc.org/article/whats-not-in-a-name-considerations-and-consequences-of-the-fields-nomenclature/

Martin, Stephanie A. “Resisting a Rhetoric of Active Passivism: How Evangelical Women Have Enacted New Modes and Meanings of Citizenship in Response to the Election of Donald Trump.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 106, no 3, 2020, pp. 316-324.

Moore, Beth. “A Letter to My Brothers.” Living Proof Ministries Blog, 31 May 2018, blog.lproof.org/2018/05/a-letter-to-my-brothers.html.

Moore, Beth. Living Proof Live. Norfolk, Virginia. 29 April 2016.

Smietana, Bob. “Accusing SBC of ‘Caving,’ John MacArthur Says of Beth Moore: ‘Go Home’.” Religion News Service. 19 Oct. 2019. religionnews.com/2019/10/19/accusing-sbc-of-caving-john-macarthur-says-bethmoore-should-go-home/.

Smietana, Bob. “Bible Teacher Beth Moore, Splitting with Lifeway, Says, ‘I Am No Longer a Southern Baptist’.” Religion News Service. 9 March 2021. religionnews.com/2021/03/09/bible-teacher-beth-moore-ends-partnership-withlifeway-i-am-no-longer-a-southern-baptist/gclid=CjwKCAjw2bmLBhBREiwAZ6ugo4mpOueGXkGUGq5qNfqgVuXU9T_eWlKMNpeX6MJ__enm87vOhcXILRoCEv4QAvD_BwE.

“Southern Baptist Leaders Release a Previously Secret List of Accused Sexual Abusers.” NPR, NPR, 27 May 2022, www.npr.org/2022/05/27/1101734793/southern-baptist-sexual-abuse-list-released.

Footnotes

[1] Lifeway Christian Resources was started in 1891 by Dr. James M. Frost after gaining approval and recognition from the Southern Baptist Convention. Lifeway remains “an entity of the Southern Baptist Convention.” (About Lifeway)

[2]An audio recording of Trump making lewd and sexualized comments about women leaked in 2016 during his run for president. Trump denounced the recording, calling the comments simply “locker room talk.” (Fahrenthold 2016)

PDF

PDF