“An American Orphan”: Amelia Simmons, Cookbook Authorship, and the Feminist Ethē

“An American Orphan”: Amelia Simmons, Cookbook Authorship, and the Feminist Ethē

Peitho Volume 23 Issue 1 Fall 2020

Author(s): Elizabeth J. Fleitz

Elizabeth J. Fleitz is an associate professor of English at Lindenwood University in St. Charles, Missouri. She teaches writing pedagogy, digital humanities, technical writing, grammar, and first-year writing. Her research specializes in the rhetorical practices of cookbooks. She has published previously in Peitho, and has also published in Harlot, Present Tense, the Sweetland Digital Rhetoric Collaborative’s Blog Carnival, and the edited collection Type Matters, among others. She is also part of the editorial collective for the Praxis and Topoi sections of Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology and Pedagogy.

Abstract: This article analyzes the rhetorical moves made by Amelia Simmons, author of American Cookery, the first American cookbook, published in 1796. Simmons identifies herself on the title page as “an American Orphan.” This article discusses that rhetorical move in terms of its historical and rhetorical context. While initially Simmons’ emphasis on her “American orphan” status might seem counterintuitive (or at least irrelevant), a further exploration into her text shows this to be a calculated risk. Simmons is capable of navigating multiple identities (a woman; an uneducated, working-class orphan) simultaneously, and using them to her advantage through her identity statements, morality statements, and her use of sentimental narrative style. From this analysis, I argue that Simmons’ use of ethos in the text demonstrates what might now be interpreted as a modern American feminist ethē emerging in the 18th century.

Tags: 23-1, Amelia Simmons, American Cookery, cookbooks, ethe, ethos, feminism, rhetoricFood Network host Ree Drummond, in the introductory section of her cooking blog The Pioneer Woman, welcomes readers saying “My name is Ree. Howdy! I’m a desperate housewife. I live in the country. I’m obsessed with butter, Basset Hounds, and Ethel Merman. Welcome to my frontier!” Cheerful and friendly, she writes in a conversational style that invites readers into her kitchen and her life as a wife and mother of four children. Simultaneously, Drummond is a television personality, businesswoman, wife, mother, cook, blogger, rancher, as well as former big-city girl. In short, she is relatable and trustworthy to a wide variety of audiences. Her various identities all play a role in her ethos construction as that chatty friend anyone would love to have. After all, who better to rely on for good recipes than a rancher’s wife?

While the popularity of Food Network and cooking blogs continues to hold strong, it is important to note that this focus on ethos construction in the authorship of cookery texts is not new. Authors have been writing their expertise into their recipes for centuries. Women authors, in particular, have found creative ways to establish their trustworthiness and claim a voice in a public space that would otherwise be unfriendly to their sex. Writing two centuries earlier, Amelia Simmons performs a similar type of rhetorical move in developing her ethos as an author. Simmons, author of the bestselling 18th-century cookbook American Cookery, offers the earliest example of American ethos construction by a cookbook author. I argue that Amelia Simmons uses what might be interpreted now as a feminist ethē (as defined by Ryan, Myers, and Jones in their 2016 collection Rethinking Ethos), as she, by speaking from her marginalized position, disrupts assumptions regarding who can be an expert. Studying Simmons’ use of identity statements, orphan trope, morality statements, and sentimental narrative style, she uses her writing to craft her expertise and claim a space for herself in the culinary tradition. This article works to uncover Simmons’ rhetorical moves and argue for their value in a feminist context. After detailing the publishing history of American Cookery, reviewing relevant scholarship on cookbooks, and providing historical background about what little is known of Amelia Simmons, I analyze how Simmons uses what would today be considered a feminist ethē to establish the trustworthiness of her cookbook.

A Revolutionary Text

Published in 1796 in Hartford, Connecticut, American Cookery’s claim to history is that it is the first cookbook purported to be American, illustrating a thoroughly American way of cooking as separate from British traditions. Only 47 pages long, cheaply bound and without a cover, this little book went on to have over a dozen printings between 1796 and 1831, with many more pirated versions (Lowenstein). It was the best-selling cookbook in the new Republic until Mary Randolph’s The Virginia Housewife of 1824 claimed the title (Hess ix). The fact that it was the first to claim a unique American identity makes American Cookery a valuable part of American history and American culinary history. The Library of Congress recognized it as one of the 88 “books that shaped America.” Cookbook scholar Janice Longone calls its publication “a second revolution–a culinary revolution.” But what was so revolutionary about it?

Only two decades after the Republic’s founding, America was still finding its way as a culture. Up until American Cookery’s publication, the only cookbooks available in the new world were republished versions of British bestsellers. This remained true even during and after the American Revolution; even though colonists railed against being ruled by the British, they still wanted to eat like them. Some of the most popular were Markham’s The English Hus-wife of 1615 and Glasse’s The Art of Cookery of 1747. The closest any cookbook had come to creating an American food culture was Eliza Smith’s 1727 volume The Compleat Housewife, republished in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1742. This book attempted to adapt its recipes to an American audience by merely deleting the British recipes that could not be replicated in America due to ingredient availability. While moderately helpful, American cuisine still had a long way to go.

In many ways, Simmons’ American Cookery is revolutionary, more than just its claim as the first American cookbook. It did more than merely delete British ingredients or plagiarize British recipes (though it did that too, which was a common practice at the time and not one that held a negative connotation like today).1 Simmons took ingredients native to the Americas and explained how to use them. She shared practices that were common to home cooks and domestic workers at the time, formalizing the practice in print. One notable first was the substitution of cornmeal (in the text called “Indian corn” or “Indian”) for English oatmeal in several recipes, such as johnnycake (see Fig. 1).

![Image is recipe for Johny Cake or Hoe Cake and reads: "Scale 1 pint of milk and put 3 pints of Indian meal, and half pint of flower—bake before the fire. Or fcald [sic] with milk two thirds of the Indian meal, or wet two thirds with boiling water, add falt [sic], molaffes [sic] and fhortening [sic], work up with cold water pretty ftiff [sic], and bake as above."](/docs/peitho/files/2020/12/Fleitz-fig-1.png)

Fig. 1. Recipe for “Johny Cake” from American Cookery (1796, Albany printing).

![Image is a recipe for The American Citron and reads: "Take the whole of a large watermellon (feeds excepted) not too ripe, cut it into fmall [sic] pieces, take two pound of loaf fugar [sic], one pint of water, put it all into a kettle, let it boil gently for two hours, then put it into pots for ufe [sic."](/docs/peitho/files/2020/12/Fleitz-fig-2.png)

Fig. 2. Recipe for preserving “American Citron” (watermelon) from American Cookery (1796, Albany printing).

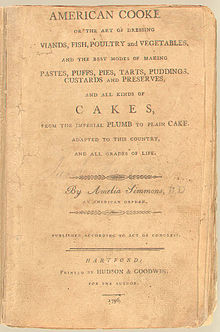

Fig. 3. Cover page of American Cookery (1796, Hartford printing).

Beyond the text’s revolutionary firsts in ingredients and language, it is, more importantly, rhetorically revolutionary. Simmons, adapting models of ethos to fit her own needs, uses a variety of strategies to become a trustworthy author. Her most curious ethos construction is on the title page (see Fig. 3), where she identifies herself, the only place in which Amelia Simmons is named in the text. She calls herself “Amelia Simmons, An American Orphan.”2 It is a simple appositive phrase, yet so curious in terms of a rhetorical move. On first analysis, it is not immediately clear what her upbringing has to do with cooking. However, it was clearly a calculated move, as Mecklenburg-Faenger argues in her study of the Charleston Receipts Junior League cookbook, “cookbooks encode information about how their compilers see the world and their places in it” (213). In narrative elements like these, Tippen notes that cookbooks demonstrate their authors’ rhetorical moves (17). Simmons’ use of the “American Orphan” identifier was just one of her choices that she hoped would lead to audiences trusting her and her expertise. Additionally, orphan status enables her to distance herself from any non-American heritage, making it easier for Simmons to claim an all-American identity, just like her cookbook. Further, orphans were often domestic servants at this time; thus, the position lent itself to a certain level of credibility in the kitchen. Through her narrative elements, Simmons constructs ethos that I claim could be identified today as feminist, even while writing in the early days of the Republic.

Cookbook Authorship and Ethos

Writing the first American cookbook, Simmons begins composing the history of American cookbooks, which can offer insight on American culture at the time. Laura Schenone, in her 2004 book A Thousand Years Over a Hot Stove, notes, “food opens a window that we can look through” (xv). This is a useful metaphor to consider the value of food. Certainly, it is much more than sustenance. Food helps us identify our culture, our community and ourselves. Scholars can study foodways—habits of others—to gain insight on cultures outside of their own. As a digest—pun intended—of food culture, the cookbook is an excellent primary resource through which to view one’s own culture and others. Karen Hess uses Janus as a metaphor to describe the cookbook’s rhetorical value, as the text looks both back and forward at once: a cookbook records culinary practice at the time of its writing, and it also influences cooking to come (xii). As a set of instructions, cookbooks are, at their most simplistic, a practical text (Collings Eves 280). But if we look further, we can see a story (Bower 2). Writing in PMLA, Susan J. Leonardi explains that a cookbook’s stories are more complex than the average linear narrative: they are embedded, layered discourses (340). While they are “gap-ridden” (Bower 2), asking the reader to fill in the gaps with her own knowledge, they are also “a narrative which can engage the reader or cook in a ‘conversation’ about culture and history in which the recipe and its context provide part of the text and the reader imagines (or even eats) the rest” (Floyd and Forster 2). Indeed, recipes demand exchange, and even “exist in a perpetual state of exchange” (Floyd and Forster 6). Leonardi notes that “Even the root of recipe—the latin recipere—implies an exchange, a giver and receiver. Like a story, a recipe needs a recommendation, a context, a point, a reason to be” (340). The ability of this genre to be a window on culture as well as a conversation about culture lends the text a space in which the author can establish her own voice, expertise, and ethos, even while remaining inside a patriarchal paradigm. In her book Eat My Words: Reading Women’s Lives Through the Cookbooks They Wrote, Janet Theophano asserts that cookbooks are “opportunities for women to write themselves into being” (9). Cookbooks, as well, are sites where women and minority writers can dispel stereotypes and establish their own voice. As a window on culture, cookbooks allow a space for marginalized voices to be heard, listened to, and above all, trusted as a knowledgeable source for cooking. The cookbook, as a cultural text, is ripe for analysis as a space for ethos construction.

There is a growing body of scholarship surrounding rhetorical analyses of cookbooks, particularly feminist rhetorical analyses, which add further credibility to the value of this subject as an area of study. Lisa Mastrangelo, writing about community cookbooks, describes them “as rhetorical artifacts that reveal much about their communities” (73), as a lens that readers can look through to understand more about the author and her context. Reading Simmons’ text, we can gain insight on her values and the values of the community around her. Even years before feminism, cookbooks illustrate how women used rhetoric to advance their message. As Mecklenburg-Faenger explains, studying cookbooks can provide scholars of women’s rhetoric “opportunities to reaffirm the presence of women’s rhetorical activities even in historical periods when women’s rhetorical performances in the public sphere were discouraged, devalued, or diminished” (213). Abby Dubisar, in her study of peace activism cookbooks, argues that these texts can “teach feminist rhetoricians the potential of domestic genres to promote activist causes and frame political identities” (61)—thus, cookbooks can do much more than simply tell us how to cook a meal.

The trustworthiness of an author is a major factor on the success or failure of a cookbook. When choosing a recipe, the reader wants reassurance up-front that the person writing it knows that the recipe will work, and that it will be worth the effort. Ever since its origins as an oral culture, the act of recipe sharing has centered around trust. Originally, recipes were asked for from women who were trusted to be good cooks, who could be guaranteed to provide a quality recipe. They were women known personally to the receiver, whether a family member, neighbor, or friend. This role of ethos is more important now that recipes have moved from an exclusively oral, shared culture between friends and family members, to a public forum where most recipes are written by people the reader will never meet, in mass-produced cookbooks or online. The cookbook constructs the writer’s ethos for the audience. One would be unlikely to choose a cookbook if the author were perceived untrustworthy. If the audience can trust the speaker, then her argument is that much more powerful. Now that the personal connection of recipe sharing is removed for modern cookbooks, today ethos is even more of a factor when determining whom to trust. As such, the cookbook is a useful text to analyze an author’s rhetorical moves regarding their credibility.

In 1796, when American Cookery was published, the rhetorical space of the American cookbook was fraught with difficulty—not only did the author need to assure readers of the text’s quality, but she also needed to claim an American ethos—one that did not yet exist, at least not in printed form. While the new Republic had existed for two decades by this point, there was no formal recognition of a distinctly American food culture. Colonists quickly learned the art of adaptation, as many English ingredients were not available in the Americas, while other, unfamiliar ingredients were plentiful. They also benefited from the Native American’s knowledge of the land, adapting their knowledge to the colonists’ tastes. Still, American food culture was nonexistent, but there was finally an author ready to take on this challenge: Amelia Simmons.

Amelia Simmons: Claiming Feminist Ethē

Simmons, as an American and as a woman, is in a challenging position. Writing the first book of truly American recipes is difficult enough, but to claim that expertise in a public forum as a woman is more difficult, as she is already in a marginalized position. Oddly enough, to address this challenge, she mentions her upbringing as an orphan (and an American one). Wilson notes that Simmons seems to have a “preoccupation” with her orphan status, bringing it up more than once in the text (20). Simmons doubles down on her marginalized status, marking herself as an orphan on the front page and reminding us of her status. She names herself in the preface as “a poor, solitary orphan.” Usually, highlighting one’s marginalization, especially as it has no obvious link to the book’s content, would not seem to be an effective use of ethos. However, there is more to this ethos construction than appears at first glance.

Feminist rhetors have developed an alternative model of ethos to describe how women and other marginalized groups gain the goodwill of their audience. Coretta Pittman, observing that Aristotle’s model of ethos is caused by deliberate choice, points out that black female rhetors are not positioned to freely make their own choices, or to engage in speaking in a public forum, as an Aristotelian model assumes (49). As Pittman argues, “Western culture has appropriated a classical model of ethos to judge the behavior of all of its citizens. However, not all of its citizens can be judged by the same standards. The legacy of racism, classicism, and sexism in American society marked individuals associated with undesirable groups” (45). For instance, a woman writer in 18th century America can exhibit as much “good sense, good moral character, and goodwill” (Kinneavy and Warshauer 179) as she would like, but she cannot do anything to control her gender, skin color, or economic status, all of which play a large role in who listens to her and how seriously she is taken. These bodily and cultural constraints also play just as large, if not larger, a role than her own speech.

Nedra Reynolds describes how feminists like Adrienne Rich, bell hooks and others explicitly locate themselves in space to establish ethos. Their identity, and character, is developed through their body’s location in space, both literal (placement of body) and figurative (position in social realm) (326). It is useful, then, to consider the marginality of an orphan in tandem with the marginality of a woman writing in 1796. In identifying herself as an orphan, she claims the margin as her location to establish ethos. While Simmons did not use the term “feminist” to describe herself, as it did not exist in the 18th century, her action of claiming the margins as part of her identity could today be interpreted as feminist. No matter their origin, feminist rhetors exist in the margins, and as such take the margin as an advantage, with bell hooks naming the margins as a “location of radical openness and possibility” (209). Instead of a traditional Aristotelian framework, feminist rhetors have shifted to one that can account for interrelationality, materiality, and agency: a model that, in their eyes, is more accurate. Similarly, Reynolds notes that “ethos […] shifts and changes over time, across texts, and around competing spaces” (326). According to Johanna Schmertz, ethos, for feminism, is not fixed or determined, but instead is a series of “stopping points at which the subject (re)negotiates her own essence to call upon whatever agency that essence enables” (86).

In a 2016 collection titled Rethinking Ethos, editors Kathleen J. Ryan, Nancy Myers, and Rebecca Jones argue for a feminist ecological approach to ethos formation–one which considers the entire ecology of a given rhetorical situation. As they claim, there is no singular women’s ethos; thus, they use the plural term ethē. They study ethos “with the acknowledgment that it is culturally and socially restrictive for women to develop authoritative ethē, yet acknowledg[e] that space can be made for new ways of thinking and artful maneuvering” (2). This model, a model of feminist ecological ethē that Ryan, Myers, and Jones promote, helps to describe the complexity of multiple relations operating and changing in response to others (Ryan, Myers, and Jones 3). Ryan, Myers, and Jones claim that their work “reconsiders ethos to offer a feminist ecological imaginary that better accounts for the diverse concerns and experiences of women rhetors and feminist rhetoricians” (5). The authors observe that “[W]omen can seek agency individually and collectively to interrupt dominant representations of women’s ethos, to advocate for themselves and others in transformative ways, and to relate to others, both powerful and powerless” (3, emphasis in original). Simmons’ rhetorical moves can be interpreted as a feminist ethē in this same way, as she, by claiming and speaking from her marginalized position, interrupts dominant impressions of how women can be considered experts. By sharing her story, Simmons advocates for herself as a successful woman and encourages other women, particularly those who are in her same economic and/or familial situation. Furthermore, Simmons frequently uses narrative elements to relate to other women, not only as a way to build herself up as an expert but to use herself as a case study: if she could do it, you can too. Simmons uses several rhetorical moves to adapt to the multiple interrelations of her rhetorical situation, considering her position as orphan, as uneducated, as a domestic servant, as an American, and as a woman. All of these are positions which, particularly in the nascent years of the Republic, are all marginal. Simmons claims the margins, not only speaking from there but also emphasizing her location there as a way to connect to readers.

However, outside of her one cookbook and its revisions, there is little else to establish Simmons’ existence, making scholars and critics question her identity, and even the ethos of the text itself. Cookbook author and editor Andrew Smith claims that it is a pseudonym, based on the lack of evidence that Simmons ever existed (Bramley). However, considering her status as an orphan, uneducated, domestic servant, the fact that Simmons is not mentioned elsewhere is not surprising. If she had not had this incredibly lucky break to publish her work, she would not have been remembered for posterity at all, alongside millions of other working-class women. Food historian Karen Hess argues that Simmons is from a Dutch heritage, considering the Dutch-language influence on her recipes and language use, described earlier (xi). Hess places Simmons in the Hudson River Valley, a logical assumption: while her book was published first in Hartford, it was then published exclusively through presses in New York state, such as Albany, Troy, and Poughkeepsie (xi). In any case, the only mention of Simmons is within this text. Other than what she tells us, that she is a working-class American orphan, the reader must infer anything else. This act of invoking meaning on historical rhetors is inherently problematic, in particular with modern terms such as “feminist,” as discussed in Michelle Smith’s review essay on feminist rhetorical historiography. Any claim made about the author’s intentions, feminist or otherwise, is complex. While Simmons didn’t use the term herself, there is insight to be gained from viewing her rhetorical moves through a feminist lens. Simmons presents a layered rhetorical approach to presenting her authority in this text in multiple ways: through identity statements, the orphan trope, morality declarations, and a sentimental narrative style to establish this feminist ecological ethē.

Ethos Construction: Identity Statements

Julie Nelson Christoph, writing about ethos as constructed by pioneer women diarists, observes how statements of identity are used frequently in women’s writing (670). Establishing and re-establishing who a woman is allows her to claim expertise, by placing herself in the context of an identity marker. Simmons, taking the “orphan” moniker, isn’t alone in her use of these descriptors: studying title pages of the female-authored cookbooks between 1796-1860 listed in Eleanor Lowenstein’s 1972 bibliography, these identity statements are used frequently.3 The nonstandard style of writing titles and naming authors that was used during this period is informative about the ways in which these women authors went about claiming expertise in a public forum. In fact, many women authors chose not to identify themselves at all. Even though women authors accounted for about 70% of cookbooks at this time (not counting new editions or reissues),4 the most common identity statement (at 33%) was by an anonymous identifier, such as using a gendered prepositional phrase to identify the author, without using her name. Some examples of this are “by an experienced housekeeper,” “by a lady of Philadelphia,” “by a Boston housekeeper,” or “by an experienced lady.” These authors prefer to establish their credibility through relatable identifiers—the assumption is that the reader would be more likely to trust a “housekeeper,” who would have the expertise of daily work, or a “lady,” who would have the authority of class to support her. Locating the author in the new world also lent credibility of being American and using a city name would afford the status marker of being in a large metropolitan area.

The next most frequent identifier for women (at 23%) was using their full name only, such as “Mrs. Mary Randolph,” “Caroline Gilman,” “Mrs. Lettice Bryan,” “Elizabeth F. Lea,” among others. The lady’s formal title was most often used as a marker of class, though occasionally it would be left off, particularly if the author was well-known. However, some of these full names may have still been pen names, as the likely fake name “Priscilla Homespun” indicates. Sometimes the full names would also include other information, such as “Susannah Carter, of Clerkenwell,” another attempt to lend credibility through location. Minimizing the author’s originality or role in the creation of the text was occasionally used, such as the participle phrase “compiled by,” as in “compiled by Lucy Emerson.”5

Used less frequently at 16% was the use of titles, not first names, for women authors, such as “Mrs. [Lydia Maria] Child,” “Miss Leslie” (referring to fiction writer Eliza Leslie), or “Mrs. [Hannah] Glasse.” Other times, the author’s title and last name was used in the title of the cookbook itself, such as “Miss Beecker’s domestic receipt book.” This was another way class markers were used to build the ethos of the author.

Below this at 15% was using job descriptions alongside the author’s name for women authors. Some examples were “Mrs. Mary Holland, author,” “Miss Leslie, author of Seventy-Five Receipts,” “Mrs. Child, author of the Frugal Housewife,” and “Eleanor Parkinson, practical confectioner, Chestnut Street.” This use of job title is a departure from how women authors were normally represented, as these titles are a marker of economic power, even from a marginalized class position.6

Without a doubt, the most curious of all these identity statements is Amelia Simmons’ “an American orphan.” Her confidence in claiming on the title page, and then reasserting in the preface and conclusion, this marginalized identity—even as it has no link to cooking expertise—is initially confusing. Why would someone want to doubly marginalize themselves, particularly in a situation where she wants to be seen as an expert? Her confidence appears to rewrite the script on assumptions about marginalized groups—one can be a woman, a domestic worker, and an orphan—and still be a published expert. Walden interprets Simmons’ orphan identity statement as her ability to turn a perceived weakness into a strength, relying on the readers’ lack of knowledge (and therefore assumptions) about her and her lineage:

She is unknown as an author, and, as a servant, she has no particular authority—or even autonomy—to claim her work as her own. Yet she turns this lack into a source of power in its own right by suggesting that her unknown origins and lineage represent the new republic she seeks to construct, both physically and ideologically, through her recipes. (37)

Even if the reader cannot relate to Simmons’ childhood, she can respect her for demonstrating such a quintessentially American value of pulling herself up by her bootstraps, coming from nothing and turning into a success, solely through hard work.

Ethos Construction: The Orphan as Literary Trope and Rhetorical Move

The orphaned child protagonist has been a frequent literary trope for centuries, and Simmons takes advantage of this familiarity in her text as another way she establishes ethos with the reader. The vision of an abandoned, desperate child pulls the reader into the story through sentimentality. Notably, Henry Fielding’s 1749 bildungsroman The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling traces the rise of the titular character, an illegitimate child abandoned by his mother, who is raised by a kind, wealthy pair of siblings. In the novel, Tom’s illegitimacy is a permanent mark on his identity, closing many doors along the way. His orphan status is the major complication of the novel, and it turns out to be something he can never overcome. Tom’s concluding happiness is due more to luck than rising status—indeed, it is his lack of any known lineage that motivates much of the book’s conflict, proving that the orphan trope is ripe for dramatic exploitation.

Similarly, many young protagonists begin their stories as an orphan, or are orphaned early on. From Bronte’s Jane Eyre, to Jane Fairfax in Austen’s Emma, to Pip in Dickens’ Great Expectations, orphans are a frequent character type, used for dramatic or sentimental effect. Writer Liz Moore explains the usefulness of orphan characters in this way: “The orphan character—especially one who is an orphan before the novel begins—comes with a built-in problem, which leads to built-in conflict” (para. 8). The lack of a stable family has often been a source of conflict in storytelling, even today. One cannot discuss orphans in contemporary literature without mentioning Harry Potter, for instance. To be an orphan means to go against the most commonly-held values of society: the strength of the family unit. Orphans lack stable role models; indeed, most fictional orphans are quickly taken in by others and struggle to find their way in society without guidance. Thus, the dramatic impact of an orphan’s rise to success is greater, as it is hard-fought (and, to the writer, “fictionally useful” (para. 11) as a story arc, according to scholar John Mullan). Moore notes of her own choice in writing orphan characters, “For me, at least, writing about orphans is a way to write through the terror of being alone in the world,” thus making the orphan’s struggle a universal one. In an orphan’s story, the reader experiences more highs and lows as the character starts from nothing and struggles to achieve greater. The orphan’s journey from outsider to accepted makes their character type a “useful trope for novelists to think about what it means to become a subject” (König 242).

Similarly, Amelia Simmons plays up her orphan status as a way to engage the reader, impressing upon them her lifelong struggle to overcome her low birth. Simmons portrays herself as a success story. She pulled herself up by her bootstraps despite the odds and intends to serve as an inspiration for others to work hard. In her preface to American Cookery, Simmons writes that it is exactly her character, her ability to develop an appropriate ethos, that is a large part of her success:

It must ever remain a check upon the poor solitary orphan, that while those females who have parents, or brothers, or riches, to defend their indiscretions, that the orphan must depend solely upon character. How immensely important, therefore, that every action every word, every thought, be regulated by the strictest purity, and that every movement meet the approbation of the good and wise. (5)

Simmons knows the importance of constructing an effective ethos to achieve her goals. While the “regulation” she writes of in the above excerpt implies a belief in the fixed, Aristotelian model of ethos that she must live up to, her openness in writing about such marginal subjects as her low status, orphan identity, and struggles as an independent woman demonstrates a use of ethē. Simmons claims these marginal identities as her own, disrupting the usual representation of women in this time period and instead embraces a more complex approach to her character development that allows her to advocate for and relate to other women, whom she hopes will achieve as much as, or even more than, she did.

By sharing her story, Simmons portrays herself as a symbol of inspiration to other women. She does not get into details about her own origins, only referring in general terms to her tragic, low origin. It is worth noting, however, that she may be using the orphan trope to distance her identity from any non-American heritage. If she does not know her origins, it is much easier to claim an all-American identity, further impressing on her readers the authentic American-ness of her text. Simmons only makes vague reference to her origins in her preface, mentioning how she was forced into domestic work due to her low status. In fact, low-status women seem to be her target audience, as indicated by this disclaimer: “The Lady of fashion and fortune will not be displeased, if many hints are suggested for the more general and universal knowledge of those females in this country, who by the loss of their parents, or other unfortunate circumstances, are reduced to the necessity of going into families in the line of domestics” (3). Simmons expects that other domestics like her, or those who expect to become a domestic servant, will be the most likely to use this cookbook. She sees it as a women’s survival manual. This text is not one that, like many of today’s cookbooks, can be leisurely browsed, while enjoying the descriptions and illustrations of food, fantasizing about one’s ability to recreate these meals at home. It is a workbook, meant to help women get on their feet and become a success—like this American orphan.

Ethos Construction: Morality Statements

Simmons additionally develops her ethos through her use of morality statements. Her references to morality imply her own values, which line up with common beliefs of the time. If nothing else, these morality statements are Simmons’ most successful attempt to relate to her reader and show how much she is like them, no matter her childhood experiences. As Simmons explains in the preface, the purpose of this text is to prepare women for “doing those things which are really essential to the perfecting them as good wives, and useful members of society,” aligning domestic work with virtue and reasserting the value of hard work. She also criticizes women who ignore tradition and only pay attention to fads, saying “I would not be understood to mean an obstinate preference in trifles, which borders on obstinacy,” and argues the value of “those rules and maxims which have stood the test of ages, and will forever establish the female character, a virtuous character.” Her statements connecting female virtue with domestic work anticipate the later Victorian era “cult of domesticity” that privileged women as the moral center of the home. Skill in the kitchen was often a measure of women’s moral worth—which complicated the argument that cooking was a skill to be learned, since morality was believed to be inherent (McWilliams 393). That issue would be handled later in the Victorian era, during the cooking reform movement, that encouraged formal training in cooking and standardized and simplified the cooking process, taming the kitchen for young women who had never learned how to cook but were expected to do so.

In these value statements, Simmons implies her belief that expertise in cooking is a virtue, and as such essential to becoming a good woman. She also conflates the female character with tradition. For instance, only a good woman would know to use the already-established cooking methods rather than experimenting with fads. Through both her identity statements and her morality statements, Simmons negotiates her ethos with her readers, proving that while she may have come from a marginal upbringing, she still holds claim to mainstream values. Her marginalization of herself works to make a point about the complexity of identity. Simmons upends readers’ assumptions about her, demonstrating how much she and the reader have in common, even though the reader may not think so at first glance.

Ethos Construction: Sentimentality

Finally, Simmons builds her ethos within a sentimental narrative style. Even though it might initially seem curious that she mentions her upbringing as an “American orphan,” she can get away with it because she uses it to seek pity from the audience and thus garner more attention than the average, more relatable identity statement would. While sentimental narrative did not reach its peak in popularity until novels of the mid-19th century (Uncle Tom’s Cabin being a famous text in this style), Simmons again anticipates this style, using it to her advantage and setting herself up to be pitied.7 She emphasizes the tragedy of her orphaned experience in the preface, noting her lack of choice in her employment as domestic servant. While she is sharing her sad tale of growing up, Simmons still comes back to her expertise–implicitly claiming her expertise was gained through her struggle. She positions herself as wise primarily because she lived through this lonely existence, and praises independence as key to her salvation: “the orphan […] will find it essentially necessary to have an opinion and determination of her own” (3). Simmons notes that this independence is essential, as an orphan has no one else to guide her. Simmons presents herself as unfailingly honest, even within this sentimental style. For all the praise she gives herself for her bootstraps mentality, she also recognizes her limitations. In the preface, she reminds the reader that “she is circumscribed in her knowledge,” implying a lack of education, not surprising for a working-class woman of the time (5). She again reminds readers of her deficit in an extra preface added to the revised and corrected second edition, asking the reader who finds fault with her recipes to remember “that it is the performance of, and effected under all those disadvantages, which usually attend, an Orphan” (7). In her discussion of the rhetorical power of sentimentality, Coretta Pittman uses author Harriet Jacobs as an example of the rhetorical impact of sentimental narrative; Pittman describes how Jacobs defines her authority through exposing her marginality by narrating in sentimental form, proving that sentimental style is rhetorically useful to gain credibility with the reader (55). Through this sentimentality, Simmons succeeds in gaining the goodwill of her readers. Her style heightens the pathos of her situation, encouraging the reader to first pity her, then be in awe of her strength. Even if the reader had never experienced domestic work or was never orphaned, she understands universal human experiences of being alone or having one’s reputation be questioned. This is exactly what Jane Tompkins in her book Sensational Designs claims is the usefulness of sentimental narrative—that it helped women claim power; it helped them define themselves and claim status in a public forum (160). Though the reader may view this narrative as over-the-top today, Simmons is able to relate to the reader of her text on a personal level. Simmons uses this style to claim her identity and her values, knowing it will speak directly to other women and help them relate to her, trusting her expertise in the process.

Conclusion: American Cookery as Melting Pot

When asked why American Cookery is still considered a major American cookbook, scholars argue that this text was the first to blend British and American cultures together (Hess xv). It brought native American ingredients together with British methods to create a new melting pot of a food culture. This “melting-pot” metaphor is timely; while the metaphor is normally associated with the early 20th century, it was used much earlier, appearing in print as early as 1782,8 making it entirely possible that Simmons was aware of the idealistic assimilation of cultures as a benefit to the new world. This synthesis of cultures mirrors Simmons’ ethos construction as well; negotiating her location as American, as an orphan, as uneducated, as working-class, and as a woman, with her position as author of this text, a nationwide bestselling cookbook. Through her use of identity statements, the orphan trope, morality statements, and sentimental narrative style, Simmons effectively develops what might be termed today as a feminist ethos—or, more accurately, ethē, to identify for the first time in print as both an American and as a trustworthy cook. Even as Simmons blends together her various identities, she resists assimilation. Instead, her use of ethē in this context operates as an interruption, as someone with multiple marginal identity markers gains enough of a voice in American print culture to become a bestselling author. Similar to Food Network star Ree Drummond navigating her varied identities through her blogging, Simmons is able to negotiate multiple relations existing in this rhetorical situation, as she simultaneously presents herself as having multiple identity markers of woman, orphan, working class, and uneducated. For the first time, Simmons establishes an ethos that is recognizable to modern audiences, one that accounts for multiple identities and negotiates all of them with the audience: ethē. She composes an American ethos, demonstrating through her narrative that one can come from a poor childhood, grow up doing manual labor, and still become a bestselling author, all through hard work and the right attitude. This is the quintessential “American Dream,” demonstrating the potential for success in the new Republic. This myth that American Cookery perpetuates feeds Simmons’ own ethos, as well as the ethos of her new nation. The text, to use Hess’s Janus metaphor, looks back and forward at once, looking back to record and claim a narrow (white, upper-middle-class) definition of American foodways, and looking forward to influence that narrow cultural definition for years to come. Thus, through this ethos construction, Simmons is able to claim a space for herself to speak within the public sphere and lay the groundwork for generations of female cookbook authors to come.

Endnotes

- Despite her efforts to build ethos with her readers, it is important to acknowledge that Simmons herself engaged in questionable authoring practices. Simmons plagiarized individual recipes and entire sections (the Syllabubs and Creams section in particular) from Susannah Carter’s 1772 bestseller The Frugal Housewife (Beahrs). While this practice of copying recipes was common, every copied British recipe Simmons uses undercuts her claim to be an “American” cook. In fact, a close look at the recipes of American Cookery shows that for the most part, English methods and trends are used to such an extent that it is still more English than it is really American (Hess xv). For instance, her patriotic “Election Cake” and “Independence Cake” in the second edition is a play on British baking trends, re-named for an American audience (Hess xiv). For all its claim to originality, American Cookery is still English at its heart, with only a veneer of American. This use of English foodways traditions still helps Simmons claim her expertise, though, as readers can more readily identify with those familiar recipes and have a touch of nationalistic pride for the American spin she puts on them.

- Across the thirteen reprints of American Cookery, the title page identity statement changes a few times. In 1808, 1814, 1819, and 1822, the edition lists the author as “an American orphan,” or just (in the case of the 1831 edition) “an orphan,” without her full name (Lowenstein).

- Using Eleanor Lowenstein’s 1972 bibliography, between the years 1796—1860, each entry was coded for gender and for identity statements. Coding for gender involved either identifiable gender (whether by first name, title, or personal pronoun) or implied or likely gender (such as reference to “housekeeper” being likely female). For the small percentage of texts (less than 1%) where gender was unidentifiable, those were left out of the results. Only female gendered entries were considered in this analysis. Coding for identity statements involved any descriptors regarding the author’s knowledge, expertise, work history, publication history, or personal or professional life. So as to not skew the results, only the first publication of each cookbook was considered; repeat entries and new editions were ignored.

- Out of 103 total cookbook entries surveyed between 1796—1860, 72 were written by women and 41 by men. Only women authors were analyzed in this study.

- In the case of Lucy Emerson, the phrase “compiled by” is also honest: Emerson’s 1808 New-England Cookery plagiarized everything but the title from American Cookery.

- Not surprisingly, they are also most similar to male cookbook authors’ identity statements. The majority of male cookbook authors’ identity statements (58%) were the use of job descriptions alongside a full name, such as “Thomas Chapman, wine-cooper” and “Samuel Child, porterbrewer, London.”

- The orphan-made-good trope was a familiar one in sentimental fiction, banking on the pathos of the marginalized, abandoned child to tell a coming of age story where the orphan, left to his or her own devices outside of the familial system, is allowed to be upwardly mobile due to the lack of family connection (Walden 37-8).

- The melting-pot metaphor was first used in 1782, in Letters from an American Farmer by French immigrant J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, in his description of American identity: “individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of man” (Crèvecoeur).

Works Cited

- Beahrs, Andrew. “The Mysterious Corruption of America’s First Cookbook.” The Atlantic, 7 Dec 2010. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- “Books That Shaped America.” Library of Congress. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- Bower, Anne, ed. Recipes for Reading: Community Cookbooks, Stories, Histories. U of Massachusetts P, 1997.

- Bramley, Anne. “New Nation, New Cuisine: The First Cookbook to Tackle ‘American Food.’” National Public Radio, 3 Jul 2015. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- Christoph, Julie Nelson. “Reconceiving Ethos in Relation to the Personal: Strategies of Placement in Pioneer Women’s Writing.” College English, vol. 64, no. 6, July 2002, pp. 660-679.

- Collings Eves, Rosalyn. “A Recipe for Remembrance: Memory and Identity in African-American Women’s Cookbooks.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 24, no. 3, 2005, pp. 280-297.

- Crèvecoeur, Hector St. John de. Letters from an American Farmer. London, 1782. Project Gutenberg. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- Drummond, Ree. The Pioneer Woman. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- Dubisar, Abby. “Promoting Peace, Subverting Domesticity: Cookbooks against War, 1968-83.” Food, Feminisms, Rhetorics, edited by Melissa A. Goldthwaite. SIUP, 2017, pp. 60-76.

- Floyd, Janet, and Laurel Forster. “The Recipe in its Cultural Contexts.” The Recipe Reader, eds. Janet Floyd and Laurel Forster, Ashgate, 2003, pp. 1-11.

- Hess, Karen. “Historical Notes on the Work and its Author, Amelia Simmons, an American Orphan.” Simmons (Albany, 1796 facsimile), pp. ix-xv.

- hooks, bell. “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness.” Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction, edited by Jane Rendell, Barbara Penner, and Iain Borden, Routledge, 2000, pp. 203-209.

- Kinneavy, James L., and Susan C. Warshauer. “From Aristotle to Madison Avenue: Ethos and the Ethics of Argument.” Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory, edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, Southern Methodist UP, 1994, pp. 171-190.

- König, Eva. The Orphan in Eighteenth-Century Fiction: The Vicissitudes of the Eighteenth-Century Subject. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- LaRue, Jennifer. “America’s First Cookbook.” Hog River Journal, Spring 2006. Connecticut Explored, 17 Jun 2016. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- Leonardi, Susan J. “Recipes for Reading: Summer Pasta, Lobster à la Riseholme, and Key Lime Pie.” PMLA, vol. 104, no. 3, May 1989, pp. 340-347.

- Longone, Janice. “Introduction to the Feeding America Project.” American Cookery. Feeding America: The Historic American Cookbook Project, Michigan State University Libraries. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- Lowenstein, Eleanor. Bibliography of American Cookery Books 1742—1860. American Antiquarian Society, 1972.

- Mastrangelo, Lisa. “Community Cookbooks: Sponsors of Literacy and Community Identity.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, Autumn 2015, pp. 73-86.

- McWilliams, Mark. “Good Women Bake Good Biscuits: Cookery and Identity in Antebellum American Fiction.” Food, Culture & Society, vol. 10, no. 3, Fall 2007, pp. 389-406.

- Mecklenburg-Faenger, Amy. “‘Hear the Table Call of the South:’ White Supremacist Rhetoric and the 1950 Charleston Receipts Junior League Cookbook.” Peitho, vol. 20, no. 2, Spring/Summer 2018, pp. 212-232.

- Moore, Liz. “Why Do We Write About Orphans So Much? Examining an Eternal Literary Trope.” LitHub, 18 Jul 2016. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- Mullan, John. “Orphans in Fiction.” Discovering Literature: Romantics & Victorians, British Library, 15 May 2014. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- Pittman, Coretta. “Black Women Writers and the Trouble with Ethos: Harriet Jacobs, Billie Holiday, and Sister Souljah.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 1, Winter 2007, pp. 43-70.

- Reynolds, Nedra. “Ethos as Location: New Sites for Understanding Discursive Authority.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 11, no. 2, Spring 1993, pp. 325-338.

- Ryan, Kathleen J., Nancy Myers, and Rebecca Jones, editors. Rethinking Ethos: A Feminist Ecological Approach to Rhetoric, SIU P, 2016.

- Schenone, Laura. A Thousand Years Over a Hot Stove: A History of American Women Told Through Food, Recipes, and Remembrances. Norton, 2004.

- Schmertz, Johanna. “Constructing Essences: Ethos and the Postmodern Subject of Feminism.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 18, no. 1, Autumn 1999, pp. 82-91.

- Simmons, Amelia. American Cookery, or the art of dressing viands, fish, poultry, and vegetables, and the best modes of making pastes, puffs, pies, tarts, puddings, custards, and preserves, and all kinds of cakes, from the imperial plum to plain cake: Adapted to this country, and all grades of life. By Amelia Simmons, an American orphan. Hartford: Hudson & Goodwin, 1796, first edition. Facsimile, with introduction by Melissa Clark. Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2012.

- —. American Cookery…Albany: Charles R. and George Webster, 1796, second edition. Facsimile, with introduction by Karen Hess. Applewood Books, 1996. Google Books. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- —. American Cookery…Hartford: Printed for Simeon Butler, Northampton, 1798, 1st edition, 2nd printing. Feeding America: The Historic American Cookbook Project, Michigan State University Libraries. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- Smith, Michelle. “Review: Feminist Rhetorical Questions and the Broadening Imperative.” College English, vol. 82, no. 3, Jan. 2020, pp. 326-341. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- Theophano, Janet. Eat My Words: Reading Women’s Lives through the Cookbooks they Wrote. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Tippen, Carrie Helms. “Writing Recipes, Telling Histories: Cookbooks as Feminist Historiography.” Food, Feminisms, Rhetorics, edited by Melissa A. Goldthwaite. SIUP, 2017, pp. 15-29.

- Tompkins, Jane. Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790—1860. Oxford UP, 1986.

- Walden, Sarah. Tasteful Domesticity: Women’s Rhetoric & the American Cookbook, 1790—1940. U of Pittsburgh P, 2018.