CHAPTER TEN

Practitioner Action Research on Writing Center

Tutor Education: Critical Discourse Analysis

of Reflections on Video-recorded Sessions

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Mary Pigliacelli

Long Island University

In a March 2017 email on the WCenter listserv, Lisa Hacker, a writing center supervisor, posted a request for help with how to respond to a tutor who had become extremely upset after a session, walking out of the center during a discussion on other strategies he might have used, and later breaking down in tears. Hacker wrote: "I know his heart is in the right place, but he is not as self-reflective as a tutor needs to be, and whenever we discuss this issue we have to tip-toe because we don't want to hurt his feelings." An outpouring of empathetic and pragmatic responses followed, providing Hacker with both commiseration and a variety of ways to consider how to support this tutor. This discussion highlighted for me a challenge I was also facing as a new director: how to engage in the intricate dance of understanding and supporting tutors as I tried to help them learn how to effectively co-construct collaborative sessions with students. What could I do to support tutors as they struggled with the common dilemma of balancing their own expertise and power in a session with a student's knowledge and authority? How could I take a deep dive with my tutors into what was happening in their sessions to help us see the dynamics of these co-constructed interactions more clearly and, as Andrea Lunsford encouraged decades ago, "to examine carefully what we mean by collaboration and to explore how those definitions locate control" (4). I wanted our center to be, as Lunsford described, "informed by a theory of knowledge as socially constructed, of power and control as constantly negotiated and shared, and of collaboration as its first principle," which, as she noted "presents quite a challenge" (4).

This chapter is an account of my practitioner action research to develop and study a process for supporting the tutors in our center who struggled with co-constructing productive collaborative sessions with students, as well for helping us all become more effective collaborative practitioners. These goals led to my research questions:

- Would it be helpful for tutors to be able to observe themselves interacting with students in sessions and, if so, would a process of video-recording and reflecting on sessions be an effective staff development strategy?

- Specifically, would this process help tutors to understand what they were doing/being in sessions and to become more self-reflective so that they could respond more appropriately to students in sessions?

In this chapter, I will discuss the use of video recordings of writing center sessions as a part of the tutor education in my center. I then present my research method and introduce James Paul Gee's method of critical discourse analysis (CDA) as an analytic method for interacting with tutor reflections on their videos to help deepen their reflection and learning processes. Finally, I present my analysis, which identified six areas of knowledge I needed to help tutors develop so they could co-construct effective collaborative sessions with students.

Video Recording and Tutor Training

Video recording and reflection on both constructed role-playing and actual sessions with students has been employed by writing center directors as a strategy for training tutors and helping them continue to develop their skills since the 1970s (Catalano; Hickey and Essid; Hutchinson and Gillespie; Mattison; Neuleib, et al.; O'Hear; Samuels; Santa; Zaniello). Two main themes are evident in the literature: 1) the importance of video, as opposed to either recall or audio recordings, as a tool to support reflection, and 2) the importance of recording real situations as opposed to scripted ones.

Tutors can learn a great deal when they see themselves and the student they are working with on a video recording (Catalano; Hutchinson and Gillespie; Mattison; Neuleib, et al.; Newhouse; Samuels; Santa). One reason for this is that tutors can pick up on non-verbal clues such as gestures and silences, which would be very difficult to reflect on based just on recall alone (Catalano; Neuleib, et al.; Santa). Janice Neuleib, et al. report that video recording is superior to audio recording because "a tutor listening to his or her own voice [in an audio recording of a session] can easily miss the cues of knitted brows or wandering eyes on the face of the student. When the tutor sees the videotape, however, the missed connection is easy to spot" (3). Such attention to nonverbal cues is essential, the authors note, because "nonverbal signals dictate the tone of initial contacts and may affect all future tutoring" (2). Additionally, Neuleib, et al. affirm the power of seeing oneself on video: "we had all watched ourselves on videotape and knew the dreadful truths the camera had to tell" (1). Anyone who has viewed themselves on a video knows that the experience can be hard to forget.

Tutors also learn from viewing real tutoring sessions because seeing themselves in real situations with real students highlights the relationship with the student (Catalano; Mattison; Neuleib, et al.; Samuels; Santa). This is particularly important from a co-construction perspective because it is the moment-by-moment actions and responses that create that relationship in real time. Tutors can observe how these interactions unfolded, see how both they and the student participated in creating the relationship that developed within the session, and get some perspective on what worked well or what they might want to do differently. As Sally Jacoby and Elinor Ochs affirm, "it is through all of these linguistic, paralinguistic, and nonlinguistic means that interactants play out, reaffirm, challenge, maintain, and modify their various (and complexly multiple) social identities as turn-by-turn talk unfolds" (176). And it is through the ability to observe and reflect on their own presentations of identities as well as those of the students they are working with that tutors can begin to gain more insight into these collaborative relationships.

Both of these benefits of video (visuals and real situations) can help facilitate and deepen tutor reflection (Catalano; Hutchinson and Gillespie; Santa). Additionally, Glenn Hutchinson and Paula Gillespie assert that "Directors have as much to learn from tutors' reflections and looking at videos as tutors do. Tutors trust us with segments of their videos that show their weaknesses as tutors, and their attitudes show an openness to ongoing learning. We are able to reflect on and revise our tutor education program based on this project" (123). They also note that "the videos and conferences help us discover more about our center and learn more from our tutors" (136). This was certainly my hope as we embarked on this project.

While many directors have reported positive experiences with video recording and reflection (Hutchinson and Gillespie; Mattison; Samuels; Santa), there has not been as much reported about the instances when tutors did not appear to find the process productive (Yancey). This skewing toward positive learning experiences may occur if directors allow tutors to choose whether or not they will participate in the recording and reflecting process. Katherine A. Karl and Jerry M. Kopf found that "students who need to improve their performance the most are the least likely to seek feedback." They also warn that video feedback has the potential to do some harm, possibly resulting in stress and anxiety, and sometimes even in a decline in self-esteem. Though it might seem that the ubiquity of cell-phone cameras and the frequency with which many young adults post photos and videos of themselves to social media would lessen the anxiety that tutors might feel when being asked to record sessions, tutors in our center were actually extremely anxious about the prospect of having to view themselves or having others view them on video. Karl and Kopf recommend using videotaped feedback in ways that will minimize negative results, including repeated self-viewings, since stress, anxiety, and self-focus tend to decrease with additional viewings; encouraging viewers to focus on tasks and specific behaviors; and giving feedback on videos in as private a setting as possible. I also found that acknowledging and discussing tutors' anxiety in group meetings was very helpful—we all noted how unpleasant it was to listen to our own voices and see images of ourselves in action. Armed with this knowledge, we began the process of filming and reflecting on sessions.

Practitioner Action Research: Investigating My Own Practice

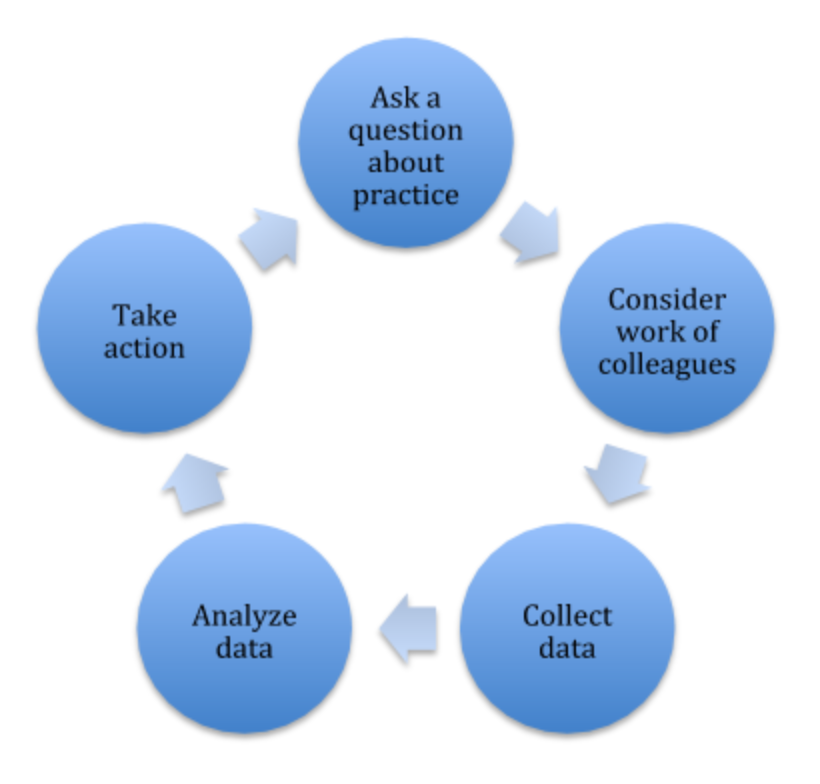

I chose Practitioner Action Research (PAR) as my framework because part of my goal was to focus on and improve my own pedagogy as a writing center director. Donna Kalmbach Phillips and Kevin Carr explain that PAR involves asking a question about one's own practice that can be answered by employing an organized problem-solving approach. It requires that the practitioner and other participants be actively engaged in the process of inquiry, that they reflect critically and recursively, and that they consider systems of power and question assumptions. Successful PAR should result in positive, ethical action at the specific site of inquiry (8). I wanted to articulate for myself what constitutes effective collaborative tutoring and how I could help tutors develop the habits of mind and the skills that would allow them to be effective, collaborative tutors. Because my research questions were very complex, I chose a research method that could consider their complexities.

|

| Figure 1. The cyclical process of Practitioner Action Research. |

As illustrated in Figure 1, The cyclical processes of PAR include identifying a focus for research, formulating a critical question, considering the work of other colleagues, collecting data from a variety of sources, analyzing data as it is being collected, cycling back around to clarify questions while interpreting and synthesizing data, and taking action.

This cyclical process is in some ways never-ending. Nicole I. Caswell, Jackie Grutsch McKinney, and Rebecca Jackson acknowledge these recursive, complex interactions: "as researchers we always approach and move through our work with interests and blind spots, hopes and misgivings, steps and missteps, satisfactions and disappointments" (15). I certainly found this to be a messy, exciting, frustrating, and ultimately, productive process.

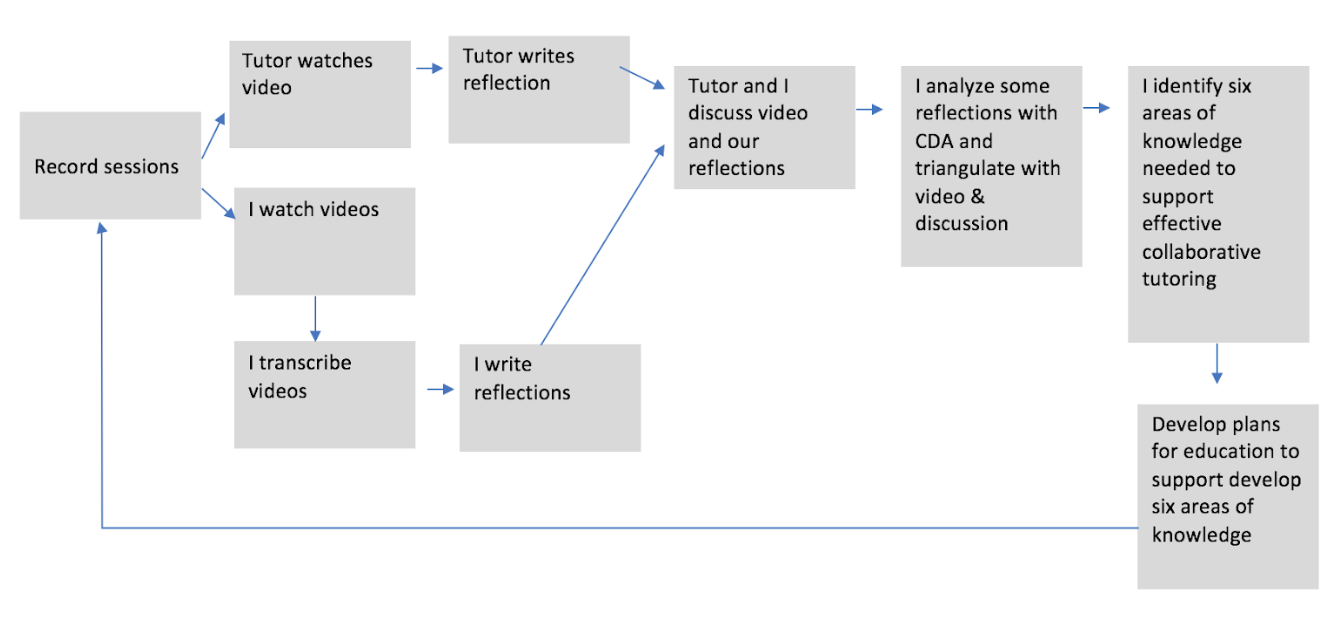

I began my PAR process by identifying my problem in the fall 2015 semester. I collected informal observation data, read literature, and attended a conference during that semester. Next, I formulated my formal research plan and collected video and reflection data during spring 2016. I began analyzing data during spring 2016, worked intensively on analysis during the summer of 2016, and continued analysis through fall 2016, winter 2017, and spring 2017 as time permitted, finalizing my analysis by the end of summer 2017. My research process is detailed in Figure 2.

|

| Figure 2. Flowchart of my PAR research process. |

Choosing Participants

All ten tutors in our writing center were required to record and reflect on sessions as part of their staff development for the spring 2016 semester. However, tutors could choose to opt out of having their data included in the research project. All ten participants volunteered to be included in the study. These participants included eight graduate students in the English MA program who identified as white females; one English MA graduate student who identified as a white male; and one undergraduate international student who identified as mixed-race and female. I focused on three participants for additional analysis because I found their situations most challenging. I perceived that these three tutors tended to take over sessions from students at times by correcting or revising their writing for them or by being overly directive in their interactions. Two of these tutors had been working in our center for at least several semesters when I arrived in 2015, so I felt some hesitancy in intervening in their established tutoring styles. The third tutor was newly hired, but, despite several discussions about how to appropriately interact with students in sessions, was still asserting her own authority in ways that did not seem to be helpful to students. All three of these final participants were white, female graduate students for whom English was their first language. Two of the tutors, Jen and Kate (names and some identifying details have been changed to preserve participants' anonymity), had been working in the center for several semesters, and one, Lori, started working at the start of the fall 2015 semester.

Collecting Data

Tutors asked students at the start of a session if they were willing to have their session recorded. If students agreed, tutors asked them to read and sign a consent form, or, in the case of students whose English language proficiency would preclude their understanding of the form, tutors read and explained the form to them. The sessions recorded were therefore limited to students who agreed to participate and were not a random sampling. One tutor, Kate, chose to record sessions with a student she had ongoing concerns about in order to try to address those concerns. The other nine tutors recorded sessions based on the willingness of students to participate. Some tutors recorded sessions with students they had worked with in the past, while others recorded sessions with students they had never worked with before.

Sessions were recorded using the iMovie application, which was already available on our center's desktop computers and utilized the camera/microphone of the computer. This proved to be both an easy and unobtrusive way to record sessions, and it allowed us to save the digital recordings to our private, password protected drive. The location of the camera at the top of the monitor provided a straight-on view of the tutor and student, whether they were working with a paper copy on the desk in front of the monitor or a digital copy on the monitor itself. Some limitations included the framing, which was not easily adjusted, so occasionally the student or tutor would move out of the frame, and it often did not provide a view of the text. Also, the microphone tended to pick up and amplify background noise. Despite these issues, the overall visual and audio quality was excellent.

Sessions were recorded using the iMovie application, which was already available on our center's desktop computers and utilized the camera/microphone of the computer. This proved to be both an easy and unobtrusive way to record sessions, and it allowed us to save the digital recordings to our private, password protected drive. The location of the camera at the top of the monitor provided a straight-on view of the tutor and student, whether they were working with a paper copy on the desk in front of the monitor or a digital copy on the monitor itself. Some limitations included the framing, which was not easily adjusted, so occasionally the student or tutor would move out of the frame, and it often did not provide a view of the text. Also, the microphone tended to pick up and amplify background noise. Despite these issues, the overall visual and audio quality was excellent.

Once tutors had recorded a video, they chose a time to sign themselves off the tutoring schedule to view the recording and write a reflection on it, guided by a list of reflection questions. Tutors submitted their reflections to me via email, and we scheduled a time to meet to discuss their videos and reflections, re-watching small sections of videos together as necessary.

I collected 12 complete packets of data (see Fig. 3), including one from Jen and two each from Lori and Kate.

Types of Collected Data

Primary Sources

- Recorded videos

- Tutor reflection of videos

- Writing Center Director's reflection of videos

- Transcript of videos

- Writing Center Director notes on discussions with tutor

Supplemental Sources

- Entrance sheet information that includes students' primary language, year in school, and major

Data Not Included

- Students' anonymous session evaluations

Figure 3. A summary of the types of data collected for the PAR research project.

Reading Reflections More Deeply with Critical Discourse Analysis

In order to read and think about the tutors' reflections with a deeper understanding, I used James Paul Gee's method of CDA. Rebecca Rogers notes that "critical discourse analysis is a problem-oriented and transdisciplinary set of theories and methods that have been widely used in educational research" (1). Many researchers report on its effective use in teacher training (Christiansen; Jalilifar et al.; Kelly; Ritz; Rogers, et al.). CDA proceeds from the theory that individuals use language to do more than just relay information to others. Gee argues that in addition to providing information, language "also allows us to do things and to be things" (How to 2). Language allows us to "take on different socially significant identities" (2). For example, a young woman who is a second-grade teacher will use language very differently when she is "being" a teacher in the classroom with her students than she will when she is "being" a young woman out with friends. In both cases, Gee notes, there are "rules" for how to be a "good" second grade teacher and a "good" young woman out with friends. Whenever we speak or write, we present ourselves in a particular way, and we hope that others will accept that performance and recognize the identity we are presenting through our use of appropriate language. Because there are "good" and "bad" ways to enact these identities, Gee argues that "in using language, social goods are always at stake. When we speak or write, we always risk being seen as a 'winner' or 'loser' in a given game or practice" (An Introduction 7). Gee's approach to discourse analysis is "critical" because it goes beyond observing features of language use to consider the deeper political sense of language that reveals hierarchical systems of power, as well as our attempts to fit within, question, or manipulate these power systems. Gee's approach, therefore, "looks at meaning as an integration of ways of saying (informing), doing (action), and being (identity), and at grammar as a set of tools to bring about this integration" (How to 8). This means that researchers can look at an individual's writing as a presentation of their social identity within a particular power structure, making it a useful tool for examining tutors' reflections on how they co-constructed sessions with students, particularly in terms of how they were understanding the power dynamics inherent in collaboration. CDA could also be effectively used independently of the video recording process, as directors could potentially apply it to any tutor reflection, such as responses to readings or session notes.

I found through this process that the video recording of actual tutoring sessions with students, when employed within a system of reflection and feedback, could be a particularly useful tool for helping tutors develop the strategies and stances necessary for responsive and creative collaborative tutoring of writing. I also found that I could improve my ability to provide feedback and education to tutors by applying CDA to their reflections.

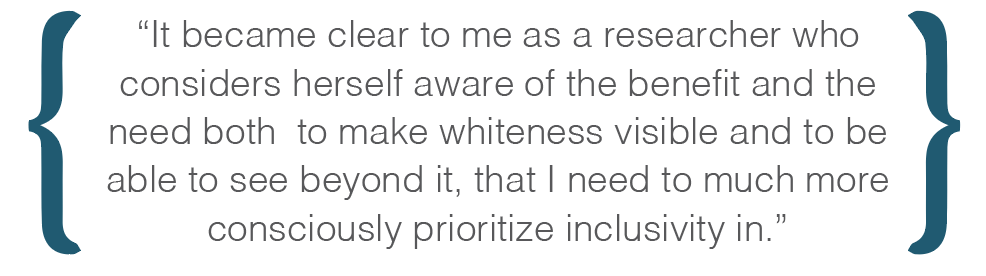

Limitations of this Study

This study is limited by its narrow focus on three white female tutors, four white female students, and the specific context of one writing center. All three tutors and all the students they recorded sessions with were also native English speakers. Generalizing from this very small and homogenous group, therefore, limits my conclusions and indicates a need to expand the study to include students and tutors who are minoritized, multilingual, male, etc. At the time of this study, of ten tutors working in our center, there was one white male tutor and one mixed-race female tutor. Students who were recorded in sessions included two black male students, one black female student, and three international students: one female from Japan, one female from Saudi Arabia, and one female from Ukraine. The remainder of tutors and students in the recorded sessions were white females. While I chose the three tutors for additional analysis based on our mutual concerns about their tutoring and for the purpose of improving the tutoring in our center, once the study was complete and I realized that this had become a white female text, written by a white female about white females, I recognized that my study would have been much stronger if I had consciously included a more diverse selection of tutors and students. Given the timeframe of this study and my desire to make changes that would directly affect students, this choice was valid. Beyond the concerns of this study, however, it became clear to me as a researcher who considers herself aware of the benefit and the need both to make whiteness visible and to be able to see beyond it, that I need to much more consciously prioritize inclusivity in future research projects. "> future research projects. Despite this limitation, the fruitfulness of the study in illuminating challenging aspects of tutor education and in articulating a possible framework for thinking about effective tutoring indicates that this process of video recording, reflection, and CDA may have benefits for other writing centers and to the field at large, and so this research model may prove useful to other writing center directors. Now that I have recruited and hired a much more diverse staff, I plan to extend this research to a more diverse group of tutors and students.

This study is limited by its narrow focus on three white female tutors, four white female students, and the specific context of one writing center. All three tutors and all the students they recorded sessions with were also native English speakers. Generalizing from this very small and homogenous group, therefore, limits my conclusions and indicates a need to expand the study to include students and tutors who are minoritized, multilingual, male, etc. At the time of this study, of ten tutors working in our center, there was one white male tutor and one mixed-race female tutor. Students who were recorded in sessions included two black male students, one black female student, and three international students: one female from Japan, one female from Saudi Arabia, and one female from Ukraine. The remainder of tutors and students in the recorded sessions were white females. While I chose the three tutors for additional analysis based on our mutual concerns about their tutoring and for the purpose of improving the tutoring in our center, once the study was complete and I realized that this had become a white female text, written by a white female about white females, I recognized that my study would have been much stronger if I had consciously included a more diverse selection of tutors and students. Given the timeframe of this study and my desire to make changes that would directly affect students, this choice was valid. Beyond the concerns of this study, however, it became clear to me as a researcher who considers herself aware of the benefit and the need both to make whiteness visible and to be able to see beyond it, that I need to much more consciously prioritize inclusivity in future research projects. "> future research projects. Despite this limitation, the fruitfulness of the study in illuminating challenging aspects of tutor education and in articulating a possible framework for thinking about effective tutoring indicates that this process of video recording, reflection, and CDA may have benefits for other writing centers and to the field at large, and so this research model may prove useful to other writing center directors. Now that I have recruited and hired a much more diverse staff, I plan to extend this research to a more diverse group of tutors and students.

Identifying Six Categories of Tutoring Knowledge

By analyzing the reflections of three tutors as they worked with four different students (Jen with Student A, Lori with Students B and C, and Kate with Student D), I identified six categories of knowledge tutors needed to develop so they could co-construct the kinds of productive sessions we were striving for in our center:

Six Categories of Knowledge

- Understand how the writing center is positioned within the university.

- Understand the procedures we use in sessions and why we use them.

- Understand how writing is structured differently in different academic genres, such as where a thesis is positioned in a text.

- Understand conventions of reference, including what counts as valid support and how sources are presented.

- Understand what language is appropriate, such as passive or active voice or the use of "I" (Linton, et al.).

- Understand writing as both a social and cognitive process.

- Understand how people learn to write.

- Understand that writing processes can be recursive and messy.

- Understand rules of grammar and syntax.

- Understand how writers attempt to achieve their purposes in their writing.

- Understand how to make visible the possible responses of audiences.

- Understand how to listen rhetorically—to be open to hearing what someone else is saying and to be listening in order to make meaning together.

- Understand how collaborative relationships between tutors and students can work.

- Have concern for students' learning.

- Have trust in students as capable and responsible people.

- Understand when and how to position students as experts or to help them position themselves as experts.

- Understand how students' languages, cultures, positionalities, and identities are at work in sessions and in their writing.

- Understand one's self as a tutor, including how one is feeling within a session.

- Be aware of what assumptions are being made about students in sessions.

- Be conscious of how one is presenting oneself in sessions.

- Understand how and when to position oneself as an expert.

Figure 4. Six categories of knowledge tutors in our writing center need to develop and share with students for productive sessions.

These six categories of knowledge are not meant to be the only kinds of knowledge writing center tutors need, but identifying this knowledge became a helpful framework for me in thinking about how to help these tutors conceptualize and develop their tutoring skills, as well as how I might construct appropriate learning experiences for the rest of our staff.

Following is a brief discussion of each type of knowledge and short summaries of my analyses, along with links to my extended analyses of tutor reflections.

Understanding how writing centers are situated within the university to create a space for writing as a "social and rhetorical activity" (Roozen) and how our procedures come from that institutional and theoretical positioning is important knowledge for tutors to have because it should undergird what they do and say within sessions. While all the tutors in our center were exposed to readings that discussed writing center work from an institutional and theoretical perspective (including Brooks; Lunsford; North; Ryan and Zimmerelli; Shamoon and Burns), and to staff discussions on these perspectives, their reflections indicated that while Jen, Lori, and Kate had all internalized some ideas about co-constructing sessions with students, each struggled to varying degrees to understand how theory could inform their individual collaborative practice.

This writing center knowledge was illustrated in their reflections through discussions of how they set up their sessions with the students they worked with.

My analysis of tutors' reflections revealed that there was sometimes a discrepancy between a tutor's understanding of the purposes behind a particular procedure, such as the use of our Entrance sheet, and the actual effect of the use of the procedure in the session. One tutor, for example, was very aware that one of our goals when filling out the Entrance sheet with a student at the start of the session is to begin to establish a relationship. She realized when watching her video that she had not accomplished this goal, providing us with an opportunity to discuss how she could align her actions and tone of voice with her goal of collaboration. Other tutors sometimes viewed procedures as administrative hurdles to get past or as "rules" to be followed. Viewing their sessions helped them understand how procedures such as filling out Entrance sheets with students, in addition to gathering potentially valuable information about the writer's situation, were designed as a way to build collaborative interactions with writers.

Tutors, therefore, should understand writing center procedures as more than rules to follow or tasks to check off a list. Tutors also need to understand the theory behind procedures, as well as to consider whether the procedures they are using are working or not, because one of the purposes of procedures should be to facilitate a collaborative relationship between tutors and students. Tutors should be able to understand when they are using procedures appropriately to co-construct collaborative sessions, when they are not using procedures appropriately or helpfully, or when procedures might be getting in the way of collaboration and therefore might need to be revised.

Patricia Linton, et al., among many other writing scholars, identifies how linguistic features of writing vary based on the disciplinary genre in which one is writing, particularly conventions of structure, conventions of reference, and conventions of language (66). While tutors cannot be expected to be experts in every disciplinary genre, they should be aware that conventions of writing are different in each discipline and that the conventions they are most familiar with may not hold true for all writing. This is an area of knowledge particularly suited to inviting collaboration with students since students will hopefully have been introduced to such conventions in the classroom and through course readings, though those conventions might not have been explicitly called to their attention. Ideally, tutors would be able to help students form a more complete understanding of conventions that, until then, students might have only been implicitly aware of. However, based on my analysis, this area of knowledge was particularly challenging for the tutors in this study to engage with, revealing an area of education I needed to further develop. These tutors struggled to share their knowledge collaboratively, and they also had difficulties in successfully calling forth the knowledge students might have had, thus making this area of knowledge one in which tutors were more likely to take authoritative stances that were less than effective. When working outside of their disciplinary comfort areas, they either became overly directive, guiding students to make moves that were not appropriate in the disciplinary genre (such as adding a thesis statement at the end of a first paragraph), or they were unsure how to discuss a student's questions about moves such as paragraph length or including evidence from sources because they were worried that they did not have the knowledge, and therefore the authority, they needed. While it would be wonderful if we could provide tutors with all the knowledge they needed to help students understand any genre, aside from being logistically impossible, authentic disciplinary knowledge is difficult to have as an outsider to a Discourse (Gee, An Introduction). Thus, it seems that it might be even more important for tutors to have the language necessary to discuss ideas about how writing varies in different disciplines and to learn strategies to help students access their own implicit knowledge. For example, tutors might ask students to consider how texts they have read and information their professors might have provided make conventions of writing in their disciplinary genres more visible. In this way, tutors and students would truly be co-constructing collaborative sessions together, with tutors providing a framework for thinking about genre conventions while students attempt to fill in that framework with specific information about those conventions when possible.

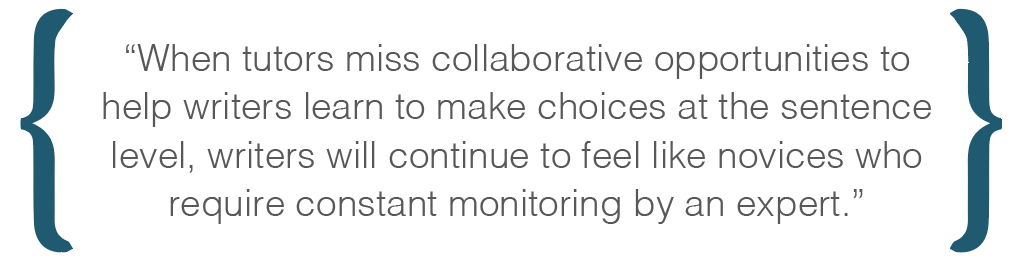

It seems obvious that writing center tutors would need to have knowledge about how writing works, both as processes and as systems of grammar and usage. In writing center discourse, the process aspect of writing knowledge is highly valued and is shared by most tutors since they have likely been made aware of their own processes as writers through their training. Sentence-level knowledge can be more fraught, however, as it traditionally tends to be taught to students as a system of rules (Dawkins), and it collides with concerns about proofreading and editing students' papers for them, rather than helping students to take a more active role in their own learning (Brooks; Harris; Lunsford; Mackiewicz and Thompson; North; Shamoon and Burns; Thonus).

My analysis of these tutors' reflections revealed that they all struggled to share their knowledge of sentence-level revision with students in ways that encouraged students' active participation in their own learning. Despite tutors' understanding that one of our goals in working collaboratively with writers is to not proofread their writing for them, when these tutors viewed their sessions on video, they were each struck with how they handled discussions of sentence-level revisions. One tutor realized she had done the work of revising for the student ("I just gave her the answer"), another saw that she had difficulty explaining what she saw happening at the sentence level in a way that would be meaningful to students ("I would like to be able to be a little clearer in explanations"), and the third noted her attempts to enforce grammar rules, rather than guide learning ("If her explanations were correct, I would agree with her, but if they were not, I would re-explain why she was wrong"). This analysis highlighted that sharing their sentence-level writing knowledge collaboratively was very challenging for these tutors, yet it is particularly important for tutors to possess rhetorical awareness of writing processes and grammar. When tutors miss collaborative opportunities to help writers learn to make choices at the sentence level, writers will continue to feel like novices who require constant monitoring by an expert. Tutors gained powerful learning experiences when they observed themselves enacting unhelpfully expert stances and observing the effect it had on students.

correct, I would agree with her, but if they were not, I would re-explain why she was wrong"). This analysis highlighted that sharing their sentence-level writing knowledge collaboratively was very challenging for these tutors, yet it is particularly important for tutors to possess rhetorical awareness of writing processes and grammar. When tutors miss collaborative opportunities to help writers learn to make choices at the sentence level, writers will continue to feel like novices who require constant monitoring by an expert. Tutors gained powerful learning experiences when they observed themselves enacting unhelpfully expert stances and observing the effect it had on students.

One essential skill writers need to master to effectively revise their own writing is to be able to see and hear their text from the perspective of an audience (Block; Ryan and Zimmerelli; Sitko). In writing center sessions, we often work toward this awareness by encouraging students to read their texts aloud, a practice which has many benefits. However, in my analysis, I discovered that when  a student was reading her text aloud, the logistics of how and when to interrupt that reading was a challenge for some tutors to navigate, and the tutor's confidence level in her own knowledge greatly affected her ability to react collaboratively. When a tutor felt unsure about her own knowledge, she might hesitate to respond to the student, but when a tutor was too confident, she would often just direct the changes she thought were warranted. Watching themselves work through these interactions in their videos helped these tutors consider how making their knowledge of rhetorical awareness more visible to students as they read through a text together could help create a more collaborative relationship.

a student was reading her text aloud, the logistics of how and when to interrupt that reading was a challenge for some tutors to navigate, and the tutor's confidence level in her own knowledge greatly affected her ability to react collaboratively. When a tutor felt unsure about her own knowledge, she might hesitate to respond to the student, but when a tutor was too confident, she would often just direct the changes she thought were warranted. Watching themselves work through these interactions in their videos helped these tutors consider how making their knowledge of rhetorical awareness more visible to students as they read through a text together could help create a more collaborative relationship.

Tutors need to have interpersonal knowledge about both the nature of the collaborative relationships they could attempt to build with students as well as how to go about building such relationships. Of course, collaborative relationships are personal and dependent upon a variety of factors such as the level of knowledge or expertise each individual brings, their perceptions of each others' abilities and knowledge, their personalities, their cultural and linguistic backgrounds, their social positionalities, and their previous experiences in collaborative situations, among many other things. Ideally, tutors will have the interpersonal knowledge that will help them navigate how and when to share authority and agency with students in sessions.

In my analysis, some tutors were more attuned than others to the relationships that developed within their sessions. Because of their potential position as the expert in charge of the interaction, it was clear that tutors needed to be able to read a student's nonverbal communication, or read between the lines of verbal communication, in order to guide the creation of a collaborative relationship. Viewing their videos revealed that while some students were experienced and/or confident enough to be full participants in a session, others needed help from the tutor to be able to position themselves as collaborators, and a tutor's understanding of a student's level of expertise affected the kind of relationship she sought to develop. When tutors saw students as novices, they were more likely to position themselves as authorities. But when tutors believed students' expertise exceeded their own, they sometimes struggled to participate effectively themselves. When tutors reflected on their struggle to understand and navigate their relationships in their reflections, this seemed to me to indicate a more sophisticated level of interpersonal knowledge because it was evidence of their understanding of the importance and challenge of participating in an effectively collaborative relationship.

Viewing tutors' interactions with students and unpacking them with a knowledgeable peer or supervisor can be particularly helpful in developing this type of knowledge, as so often the dynamics of these situations are visible in the body language of participants.

Finally, my analysis affirmed that tutors need to be aware of their own feelings, assumptions, and levels of comfort during sessions. This type of knowledge might be revealed particularly well in a reflection, since a tutor's ability or inability to see herself clearly is evident in how reflexive she is able to be. At the same time, viewing, reflecting on, and discussing their videos can potentially help tutors grow in their intrapersonal awareness, allowing them to see how they are presenting themselves, particularly when they are presenting in ways they did not realize or intend, to identify strategies that are not working well, and to discover strategies that improve their comfort in awkward or difficult tutoring situations. After watching and reflecting on her video, one tutor in particular was so struck by her tone of voice in the session that she reported she found herself thinking about it in all her other sessions. This process can therefore inform tutors' intrapersonal knowledge and reveal personality characteristics or presentations of self that influence future sessions.

However, some tutors may be resistant to deeper introspection even after going through the powerful strategy of viewing, reflecting on, and discussing recorded videos. Some tutors will lack the flexibility to reposition themselves based on the needs and expertise of the student because they are more concerned about defending their position of authority than in honestly exploring relationships. Tutors may cling to their identity as competent and knowledgeable tutors who occasionally struggle with a problem student. Such self-preservation behaviors can create ineffective tutoring strategies, and even being able to observe and acknowledge such behaviors can be challenging for some tutors. However, the impact of this kind of self-study may reach well beyond a tutor's tenure in a writing center. The tutor who found it most difficult during this study to reflect productively on her recorded sessions reported that she was still thinking about her relationship with the student she had struggled to work collaboratively with two years after she left the writing center. It was only after she had graduated and become an adjunct professor at another university that she was able to gain the necessary distance to recognize how she had been positioning herself in her relationship with a particular student, as well as what she might have done differently. This long-lasting effect is one of the benefits of having seen oneself on screen.

It is also important to note the overlap between inter- and intrapersonal knowledge, as the tutor's understanding of herself will be informed by her understanding of the student, as well as of the possibilities for their relationship, and this is key for tutors' ability to co-construct collaborative relationships with students.

These analyses reveal that tutors must access a variety of knowledges, and that they need to learn how to use these knowledges effectively within sessions. This in-depth study encouraged me to reevaluate and revise many of our education processes as described below in order to help tutors in our center develop these six kinds of knowledge.

Actions and Further Reflections

The goal that developed for this PAR was to utilize CDA to better understand the kinds of knowledge that tutors in our writing center need in order to be more responsive to and collaborative with students in tutoring sessions, and I have taken away many important ideas about tutor education from this research. As a director, I need to be able to see each tutor as an individual and to understand where they are in their thinking and knowledge development before I can effectively invite tutors into the knowledge-making process. While this is an obvious statement, it is not always so easy to carry out in practice. The critical distance created by CDA was an immense help in allowing me, and the tutors themselves, to see these interactions more clearly.

For me, this study confirms that these processes are productive: Videotaping allows us to focus on, rewatch, and review details of interactions that could not be seen as clearly through in-person observation or recall. Writing reflections allows tutors time to consider what was seen, remembered, and felt, and to begin to put those ideas into contexts as well as to process them in ways that will hopefully result in deeper learning and, ideally, changes in thinking and behavior. CDA provides even deeper insight into how tutors are understanding themselves and their interactions with students. Thus, while this process is intense and time-consuming, and therefore not recommended for use on a regular basis, it is very productive and useful as a part of an intensive staff development process. CDA was also an extremely beneficial way for me as a new director to obtain a better understanding of what effective collaborative tutoring can look like in our writing center and what I can do to support it. In particular, it helped me to understand the challenges tutors face when trying to work collaboratively with students and provided me with some guidelines to keep in mind and to share with my tutors (Figure 5).

Three Guidelines for Collaborative Tutoring

- Acknowledge the possibility of discomfort. Learning is not always comfortable, and tutors may at times become more concerned with helping writers be comfortable or with achieving the final outcomes of learning than engaging in the challenging collaborative processes that will help writers learn. Knowing how to help students work through discomfort is an important part of a collaborative relationship.

- Share the burden and the privilege of knowledge. Tutors need to know things but also to acknowledge what they don't know. Students also bring knowledge into sessions with them, even though that knowledge is sometimes invisible to them. Knowing how to balance the sharing of knowledge and expertise is essential to a collaborative relationship.

- Be open to seeing all participants clearly and compassionately. While it is very easy to become invested in our own identities as tutors, collaborative relationships require being open to the possibilities that arise when we work with a partner, and an essential first step is allowing ourselves to be aware of our pre-judgments of both students and ourselves.

Figure 5. Three guidelines for collaborative tutoring.

Writing Center Knowledge

While my analysis indicated that tutors in our center do have substantial writing center knowledge, the work done by Lisa Cahill, Molly Rentscher, Jessica Jones, Darby Simpson, and Kelly Chase on developing and supporting core principles for tutor education in this collection provides me with a hopeful model for further developing tutors' writing center knowledge in collaborative and meaningful ways. The habits of mind they identified for their centers are particularly supportive of encouraging deep and meaningful writing center knowledge, including Inquisitiveness, Persistent Engagement, Leadership, Responsibility, Openness, Flexibility, Creativity, and Reflexivity (which is essential for intrapersonal knowledge as well). My goal is to share these ideas with tutors and to see how we can integrate them into our education and evaluation processes to help them perceive a deeper connection between our theories and our practices.

Disciplinary Genre Knowledge

This area stood out to me as one particularly in need of support in our center, and it is one I am still grappling with. I have added a selection of readings to our tutor training packet, including "Introducing Students to Disciplinary Genres: The Role of the General Composition Course" by Patricia Linton, et al., and selections from They Say /I Say by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein to our staff development curriculum. To attempt to provide tutors with a more hands-on experience of thinking and writing within different genres, I included two new assignments in our initial tutor training: an MLA-style literary analysis of Randall Jarrell's The Bat Poet and an APA-style literature review on collaboration in writing center sessions. As they worked on these assignments, I asked our new tutors to set up sessions with experienced tutors and to be mindful of their thinking as writers, which they were asked to reflect on throughout the process. While tutors did not always end up with a finished paper that successfully employed the guidelines of the new disciplinary genre, the process of attempting to write in an unfamiliar genre and of participating in collaborative sessions as a writer was a very helpful way for us all to address this area of knowledge.

Writing Knowledge

This analysis revealed that tutors in our center needed additional ways to collaboratively share their knowledge of writing at the sentence-level. One activity I have added to our staff development curriculum involves asking tutors to punctuate a paragraph from which all punctuation has been removed, discuss their punctuation choices with a partner, noting similarities and differences in choices, and then discuss choices as a group. This activity has been helpful for tutors who habitually explain grammatical choices as a set of rules because tutors learn when it can be effective to discuss a rule or to discuss possible grammatical choices.

Rhetorical Awareness

One benefit of recording so many sessions for this project was that we were able to use the video recordings in order to see this area of knowledge in action. In particular, one of the sessions we recorded showed a tutor very effectively discussing the rhetorical needs of an assignment with a student and illustrated how, once the student understood her rhetorical situation, she was able to develop her own ideas very successfully. We watched this video together during staff development meetings, and tutors identified the language the tutor had used to help make the assignment clear to the student. We also considered the ways in which we can and do act as audiences for student writers by working to make our responses as readers visible to them, something that was evident to us in the videos in tutors' non-verbal responses to students, such as nodding in agreement or looking confused. One way we can work together on developing and conveying this knowledge to students is by practicing the process of "interpretive reading" in which tutors pause while reading a student's paper aloud, or ask a student to pause while reading, to summarize a section and then predict what will come next (Block; Sitko).

Interpersonal Knowledge

This analysis revealed that tutors needed additional practice in considering sessions from a student's perspective. As I read through tutors' reflections and saw that their focus was primarily on themselves and describing what they had done, rather than on the interaction between themselves and the students or on the students as learners, I realized that I had not included questions that could have been helpful in guiding them to deeper interpersonal reflection, such as asking them more specifically to consider the student in their reflection and to compare the session they were reflecting on with other sessions, or by prompting them to consider what they viewed in a theoretical context. I worked with two Graduate Assistants to analyze another tutor's reflection and, based on that analysis, to revise the Reflection Prompt for tutors.

Additionally, I found that it is essential to watch tutors' videos myself and to rewatch and discuss clips with them, since tutors were often unable to see the subtle relational shifts that occurred in sessions. These discussions added to my thinking about how to help tutors learn how to acknowledge and support students' agency and expertise within sessions. Further reading led me to the theory of self-efficacy, "an individual's belief of being capable of performing necessary behavior to perform a task successfully" (Bandura, as cited in Schmidt and Alexander). Writing center research has focused on how writing centers can help students develop self-efficacy, such as Katherine Schmidt and Joel Alexander who developed an instrument to "measure writerly self-efficacy in writing centers" and Frank Pajares who has done several studies on writers' self-efficacy. This is a new area of interest for me that I will be pursuing further in terms of training tutors, as discussed by Kelsey Hixson-Bowles and Roger Powell in this collection.

Intrapersonal Knowledge

Reflecting on the tutors' intrapersonal knowledge led me to an activity we all participated in for our fall 2016 full-staff meeting. I asked tutors to do the following:

- Write a story, in as much detail as you can, of a moment in your life when you learned something meaningful about writing. When was it? Where was it? Who, if anyone, were you with? What part, if any, did they play in your learning?

- Now bring a critical eye to that story—why might you have decided to write about that story here and now?

We shared our stories and our thinking about them, considering what our stories might tell us about how we felt as learners. Several tutors shared memories of somewhat harsh learning experiences—a professor who had given them a C based on one misplaced comma, for example—and we discussed how our experiences might be affecting how we work with students—such as a fear that if students do not "do it right" they will be penalized harshly by their professors. It was clear that tutors' internalized concerns about their own learning were being carried over into their sessions with students, and that awareness about their concerns was essential so that they could more mindfully respond to students' needs.

Suggestions for Future Research

This process leaves me with many interesting questions for future research:

- Why were some tutors more able to learn from their video and reflection experience than others?

- What conditions allow tutors to effectively reflect on a videotaped session?

- What can directors do to help tutors become more reflexive?

Some possible conditions that may affect a tutor's ability to reflect productively on their own videos include a tutor's length of tenure, level of experience, personality, openness to feedback and to collaborative tutoring strategies, and their personal investment in their development as tutors. The relationship of the director to the tutors and the culture of the writing center will also have an impact, as will the other kinds of training tutors have received and the preparation offered to prepare them for reflection. It would be interesting to see if the mode of reflection asked for would affect the reflection. For example, would informal letters, journal entries, blog entries, or other genres affect how tutors reflect on their practice? Similarly, studies looking carefully at a much wider selection of tutor reflections, similar to the description and analysis of tutor talk by many researchers including Mackiewicz and Thompson would be helpful in identifying strong reflective language and encouraging deeper and more productive reflection.

It would be valuable to extend this study to include tutors and students who are not white females. I would like to discover what other kinds of knowledge necessary to effective co-construction of sessions might be revealed through a more diverse group of students and tutors, or to gain a more complex understanding of these kinds of knowledge. For example, how might including tutors or students who are multilingual, minoritized, or male, expand the kinds of knowledge needed and strategies for employing that knowledge in writing center sessions, such as understanding how students' positionalities, identities, and cultural expectations are at work in sessions and in their writing, and understanding how such interactions are affecting student learning? Additionally, what knowledge about how students learn would be important for writing center tutors to have? And how does this kind of study impact the writers who participate in it?

I would also like to invite tutors to participate in the analysis of their own reflections, and to ask writers for their reflections on their sessions. Because writing centers are communities of practice, including all members in this project would have provided important additional insights.

I conclude by inviting other directors to participate in this type of inquiry process. Rather than relying on general rules and principles of good tutoring, we might all gain much more specific and valuable knowledge by paying attention to what effective tutoring looks like in our own centers, with our own groups of tutors and students. This method of inquiry therefore reinforces the importance of situated knowledge and invites us to explore the boundaries of our own data.

Works Cited

Block, Rebecca R. "Disruptive Design: An Empirical Study of Reading Aloud in the Writing Center." Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 2, 2016, pp. 33-59.

Brooks, Jeff. "Minimalist Tutoring: Making the Student Do All the Work." Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 15, no. 6, 1991, pp. 1-4.

Cahill, Lisa, et al. "Developing and Implementing Core Principles for Tutor Education: Administrative Goals and Tutor Perspectives." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Cahilletal.html.

Caswell, Nicole I., et al. The Working Lives of New Writing Center Directors, Utah State UP, 2016.

Catalano, Tim. "Using Digital Video for Tutor Reflection and Tutor Training." Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 28, no. 2, 2003, pp. 8-11.

Christiansen, Ron. "Critical Discourse Analysis and Academic Literacies: My Encounters with

Student Writing." The Writing Instructor, Jan., 2004.

Dawkins, John. "Teaching Punctuation as a Rhetorical Tool." College Composition and Communication, vol. 46, no. 4, 1995, pp. 533-48.

Gee, James Paul. How to Do Discourse Analysis: A Toolkit. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2014.

---. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. 4th ed., Routledge, 2014.

Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. They Say / I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing, 4th ed., W.W. Norton, 2014.

Hacker, Lisa. "Help with Tutor." Posted to WCenter listserv, 30 March 2017.

Harris, Muriel. "Cultural Conflicts in the Writing Center: Expectations and Assumptions of ESL Students." Writing in Multicultural Settings, edited by Carol Severino, et al., Modern Language Association of America, 1997, pp. 220-33.

Hickey, Dona, and Joe Essid. "It's a Wrap: Digital Video Recording and Tutor Training." Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 26, no. 6, 2002, pp. 13-16.

Hixson-Bowles, Kelsey and Roger Powell. "Self-Efficacy and the Relationship between Tutoring and Writing." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Hixson-BowlesPowell.

Hutchinson, Glenn, and Paula Gillespie. "The Digital Video Project." Tutoring Second Language Writers, edited by Shanti Bruce and Ben Rafoth, UP of Colorado, 2016, pp. 123-39.

Jacoby, Sally, and Elinor Ochs. "Co-construction: An Introduction." Research on Language and Social Interaction, vol. 28, 1995, pp. 171-83.

Jalilifar, Alireza, et al. "Critical Discourse Analysis of Teachers' Written Diaries Genre: The

Critical Thinking Impact on Cognition in Focus." Procedia: Social and Behavioural Sciences, vol. 98, May 2014, pp. 735-74.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.475.

Jarrell, Randall. The Bat Poet. Harper Collins, 1996.

Karl, Katherine. A., and Jerry M. Kopf. "Will Individuals Who Need to Improve Their Performance the Most, Volunteer to Receive Videotaped Feedback?" Journal of Business Communication, vol. 31, no. 3, 1994, pp. 213-23.

Kelly, Ryan Robert. "Discourse of Construction: A Look at How Secondary Reading Preservice

Teachers Conceptualize their Teaching." (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 11329.

Linton, Patricia, et al. "Introducing Students to Disciplinary Genres: The Role of the General Composition Course." Language and Learning Across the Disciplines, vol. 1, no. 2, 1994, pp. 63-78.

Lunsford, Andrea. "Collaboration, Control, and the Idea of a Writing Center." The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 16, no. 4-5, Dec. 1991/Jan. 1992, pp. 1-6.

Mackiewicz, Jo, and Isabelle Kramer Thompson. Talk About Writing: The Tutoring Strategies of Experienced Writing Center Tutors. Routledge, 2015.

Mattison, Michael. "Managing the Center: The Director as Coach." The Writing Center

Director's Resource Book, edited by Christina Murphy and Byron L. Stay, Routledge, 2010, pp. 93-102.

Neuleib, Janice, et al. "Using Videotape to Train Tutors." Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 14, no. 5, 1990, pp. 1-8.

Newhouse, C. Paul, et al. "Reflecting on Teaching Practices Using Digital Video Representation in Teacher Education." Australian Journal of Teacher Education, vol. 32, no. 3, 2007, pp. 51-62.

North, Stephen M. "The Idea of a Writing Center." College English, vol. 46, no. 5, 1984, pp. 433-46.

O'Hear, Michael F. "Homemade Instructional Videotapes: Easy, Fun, Effective." Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 7, no. 6, 1983, pp. 1-4.

Pajares, M. Frank. "Self-Efficacy Beliefs, Motivation, and Achievement in Writing: A Review." Reading and Writing Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 2, 2003, 139-58.

Pajares, M. Frank, and Margaret J. Johnson. "Confidence and Competence in Writing: The Role of Self-Efficacy, Outcome Expectancy, and Apprehension." Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 28, no. 3, 313-31.

Phillips, Donna Kalmbach, and Kevin Carr. Becoming a Teacher through Action Research. Routledge, 2014.

Ritz, Stacey. "A Critical Discourse Analysis of Medical Students' Reflective Writing: Social

Accountability, the Hidden Curriculum, and Critical Reflexivity." Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2680, 2014, http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2680.

Rogers, Rebecca. "Critical Approaches to Discourse Analysis in Educational Research." An Introduction to Critical Discourse Analysis in Education, edited by Rebecca Rogers, Routledge, 2011, pp. 1-20.

Rogers, Rebecca., et al. "Critical Discourse Analysis in Education: A Review of the Literature." Review of Educational Research, vol. 75, no. 3, 2005, pp. 365-416.

Roozen, Kevin. "Writing Is a Social and Rhetorical Activity." Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State UP, 2015, pp. 17-19.

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. 6th ed., Bedford/St. Martin's, 2016.

Samuels, Shelly. "Using Videotapes for Tutor Training." Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 8, no. 3, 1983, pp. 5-7.

Santa, Tracy. "Listening in/to the Writing Center: Backchannel and Gaze." WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 40, no. 9-10, 2016, pp. 2-9.

Schmidt, Katherine, and Joel Alexander. "The Empirical Development of an Instrument to Measure Writerly Self-Efficacy in Writing Centers." The Journal of Writing Assessment, vol. 5, no. 1, 2012.

Shamoon, Linda K., and Deborah H. Burns. "A Critique of Pure Tutoring." Writing Center Journal, vol. 15, no. 2, 1995, pp. 134-51.

Sitko, Barbara. "Exploring Feedback: Writers Meet Readers." Hearing Ourselves Think: Cognitive Research in the College Writing Classroom, edited by Ann M. Penrose and Barbara Sitko, Oxford UP, 1993, pp. 170-87. Social and Cognitive Studies in Writing and Literacy.

Thonus, Terese. "Tutor and Student Assessments of Academic Writing Tutorials: What is 'Success'?" Assessing Writing, vol. 8, no. 2, 2002, pp. 110-34.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. "Seeing Practice through Their Eyes: Reflection as Teacher." Writing Center Research: Extending the Conversation, edited by Paula Gillespie, et al., Lawrence Erlbaum, 2002, pp. 189-201.

Zaniello, Fran. "Using Videotapes to Train Writing Lab Tutors." Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 3, no. 10, 1979, pp. 2-3.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would especially like to thank Jeong-eun Rhee, Ph.D., for her insight, guidance, support, and friendship throughout this project, the tutors who shared their reflections with me and worked so hard to support our students, Graduate Assistants Nicole Bellinger and Azarias Perez for helping me deepen my thinking and apply our findings to our own center, and all the reviewers for thoughtful readings that encouraged meaningful revision.

BIO

Mary Pigliacelli is the Director of the Writing Center and Coordinator of First-Year Writing at Long Island University, Post. She is currently extending her research to include a diverse population of tutors.