CHAPTER FIVE

Understanding What Certifications Mean

for Writing Centers: Analyzing a

Pilot Program via a Regional Organization

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Russell Carpenter

Eastern Kentucky University

Scott Whiddon

Transylvania University

Courtnie Morin

Eastern Kentucky University

Introduction

In spring 2017, the Southeastern Writing Center Association (SWCA) began considering the possibility of a certification program for writing centers in our region. After surveying organization members about incentives and impediments to certification as well as examining certification or accreditation groups currently available, SWCA established a pilot certification program to explore ways of connecting localized writing center practices to larger, shared values about the day-to-day work of writing centers. As we explain in our WLN article on this topic, this work is grounded in conversations and debates surrounding certification writ large as local writing center concerns such as time and resource allocation (Carpenter et al. 2).

Certification is an important way to develop academic capital, lend more credibility to writing center scholarship, and help solidify foundational beliefs and approaches to learning as professionals within the field. In this chapter, we describe the process of developing our certification model and implementing our pilot. Then, we offer an analysis of pilot participant interview responses—including related digital artifacts. These responses from directors not only gave us, as SWCA board members, a way of moving forward but also allowed us a key vantage point into how certification, when integrated with a writing center's core values in mind, can impact resource development, localized representation, and tutor education and development in positive ways. Using data from a mixed-methods approach that includes 1) a survey administered to SWCA members inviting input on certification needs, desires, and challenges and 2) interviews (see "Understanding Value Added") of people from two institutions pursuing certification through the pilot program, we argue for the value of regional organizations—inclusive of colleagues who know this work well and have the potential advantage of proximity and institutional collaboration—as excellent sites for such work.

In phase one of the research process, we developed and distributed the 2017 SWCA Certification Survey to SWCA members to understand the potential benefits, challenges, and drawbacks of a certification program for the organization and its members. Results suggested the potential for a certification program to add value for tutors, writing center directors, and organizations such as SWCA, along with members' suggestions for future development. After designing a prototype certification protocol based on feedback gathered through our research process, we then implemented phase two, which invited two SWCA-member institutions—representing two different classifications of higher-education institutions—to complete the pilot certification process and to participate in IRB-approved audio interviews that offer reflections on their experiences as a way of both troubleshooting and developing our certification model. We asked substantive, open-ended questions to give participants an opportunity to reflect on the process and offer suggestions for our next wave of certification applicants.

In phase one of the research process, we developed and distributed the 2017 SWCA Certification Survey to SWCA members to understand the potential benefits, challenges, and drawbacks of a certification program for the organization and its members. Results suggested the potential for a certification program to add value for tutors, writing center directors, and organizations such as SWCA, along with members' suggestions for future development. After designing a prototype certification protocol based on feedback gathered through our research process, we then implemented phase two, which invited two SWCA-member institutions—representing two different classifications of higher-education institutions—to complete the pilot certification process and to participate in IRB-approved audio interviews that offer reflections on their experiences as a way of both troubleshooting and developing our certification model. We asked substantive, open-ended questions to give participants an opportunity to reflect on the process and offer suggestions for our next wave of certification applicants.

Pursuing certification models specifically tailored for writing centers provides the opportunity for writing center professionals to reexamine fundamental concepts inherent in professional development, specifically tutor education. These experiences—more than merely checking boxes or completing forms—are valuable to both individual academic institutions and the larger writing center community.

Writing Center Certification: A Receptiveness Study

Conversations concerning writing center certification pathways began gaining traction in 1992. Bonnie Devet and Kristen Gaetke offer an informative review of certification organizations. They present a strong argument for criteria put forward by the College Reading and Learning Association (CRLA), noting its history and focus on individual tutor certification. In contrast, Joe Law posits a need for large-scale, writing center-specific processes, citing the then fairly new National Writing Centers Association (1995). Law as well as Devet and Gaetke recognize the challenges therein—including costs, paperwork, and buy-in—yet both arguments frame such affiliations as ways to bolster the institutional perception of writing center labor: "Unfortunately, many writing centers are still perceived as ancillary to 'real' instruction and the writing center staff regarded as second-or-third-class members of the academy" (Law 155). Like Joe Law, Jeanne Simpson and Barry Maid use "accreditation" to describe a certification process and see it as a form of "academic capital" (124) that can "lend credibility to writing center scholarship" (125) and potentially help demystify writing center work to those outside of our ranks. "Accreditation," Simpson and Maid argue, "remains the currency of the academic realm" (128). Throughout this conversation, certification functions as a rhetorical act.1

Although accreditation is a national concern within academia, Julie Simon values local landscapes when considering national certification possibilities. After attempting to develop a model for her own program, Simon collaborated with her staff to adjust the CRLA requirements with tasks that are focused on supporting campus literacy, and "As a result, [Simon] ended up with a definition that characterized certification as a process through which tutors would insert themselves into the system not as a mere cog, but as something akin to a wrench" (1). Such a process directly mirrors writing center practices, offering "an approach to certification that would allow [tutors] to move from the margins of academic life to the center of our center" (3).

With these thoughts in mind, we began exploring certification models with both hope and skepticism. Our own questions echoed Simon's: "How will a certification program further our center's practical and theoretical goals? What should certification offer tutors beyond a line in their credentials file? How might it benefit our individual program and our discipline?" (3). Like Law, we value field-driven expertise, with criteria developed by writing center professionals. On the other hand, like Devet, as well as Simpson and Maid, we held reasonable concerns about the labor in preparing the type of large scale, Southern Association of Colleges and Schools-level work that involves site visits and other well-intended but time-consuming practices as Law proposes. Along the way, like Simpson and Maid (drawing on a WCenter listserv comment by Lisa Ede), we worried that an accreditation model could "be misused" (131) and easily reinforce a problematic misunderstanding of the university as a corporation.

As directors at radically different centers—a historic, small liberal arts college and a regional comprehensive university with a large writing center—we especially appreciated Simon's sense of local flexibility. For example, Transylvania uses a required practicum course and bi-weekly staff meetings to support undergraduate tutor development, as classes are the coin of the realm in a small college setting. In contrast, EKU implemented the Developing Excellence in Consultant Knowledge (DECK) system, a hybrid, systematic, and scalable education program that promotes collaboration between consultants with a mixture of online, metacognitive activities, and discussion-based, in-person seminars (Morin and Ralston; Ralston and Morin). Such differences in training reflect local landscapes. As researchers, we were curious to explore how certification might help support substantive staffer education.

We questioned the value of certification not directly anchored in writing center experience that goes beyond individual sites. Organizations such as College Reading and Learning Association (CRLA), National College Learning Center Association (NCLCA), and Association for the Tutoring Profession (ATP) are long-standing and well-designed. As administrators, we applaud how these groups use scaffolded learning, formal outcome planning, and documentation and reflection. We admire how organizations such as these value institutional stability, ethical behavior, and diversity training. They should continue to be seen as worthy sites of support. However, they are not explicitly designed to review writing center and institution-driven practices (which might include teaching composition processes or foundational understandings of writing center ethos to peer tutors). One could argue that there is little mention of "writing" at all.

As we developed our shared understanding of accreditation challenges (via readings, survey work, and ongoing conversations with colleagues), we considered how regional organizations like SWCA might offer the ideal audience, able to draw upon the rigor of peer review with important localized knowledge of writing center training practices, trends, and needs without the potentially cumbersome logistics of a national or international site for certification. In recent years, regional writing center organizations have grown in both size and status. SWCA, for example, now features its own peer-reviewed journal, Southern Discourse in the Center (SDC), and hosts an annual conference with over 250 attendees per year. These organizations maintain rigorous criteria for events yet are small and familiar enough for both experienced and new writing center professionals to take part. Regional organizations allow program leaders the chance to validate their efforts or learn emerging approaches employed in one center that might be beneficial for another in ways that are meaningful and manageable. Accreditation agencies such as the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools and Middle States Commission on Higher Education value third-party assessments. For example, MSCHE offers a line in its rubric focused on assessment by third-party providers. With this in mind, we turned to our good neighbors in the Southeast.

Questions and Answers: Establishing a Need

Our process began with several informal conversations at the 2015 Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) in Tampa, FL, when SWCA board members reviewed existing frameworks and shared their perspectives on potential certification approaches. This early input shaped ongoing considerations, including:

- needs of writing centers in the Southeast

- opportunities to show writing centers' institutional and regional value

- ways to link localized writing center work with best practices

- implications of certification processes to demonstrate value and

- values placed on certification processes by potential participants.

While these conversations proved productive, they also suggested complexity. Participants involved at that stage also realized the need for input from disciplinary leaders to shed light on the benefits and drawbacks of a certification program, in addition to the design, requirements, or language used to describe this process. Furthermore, discussions revealed the need to consider the variety of institutional sizes and missions represented.

With these considerations in mind, the SWCA Research & Development Committee (initially convened to explore the possibilities of and challenges with certification) designed an IRB-approved survey (see "2017 SWCA Certification Survey Questions" under "Resources") that included multiple-choice and open-ended questions, which was distributed to 185 SWCA members during the spring 2017 semester with a response rate of 21.7% (40 responses). The survey questions allowed us to demarcate the priorities of writing centers in the region. Although we recognize that writing centers might pursue certification for many reasons, the survey offered our colleagues the opportunity to share both motivations and concerns.

Of the participants, 87.2% (35 participants) of centers were not certified through existing organizations. However, 52.5% (21 participants) had explored certification but not pursued it, offering a range of reasons. For example, some respondents noted that it was not easy to make and/or maintain contact with existing certifying entities. Others saw the required fees (in contrast to their own strained budgets) as an impediment. Of course, time and other resources were also significant challenges, yet such allocations might be seen as more worthwhile, according to participants, if certification were more explicitly grounded in the daily work of writing centers.

Importantly, 50% (20 participants) valued explicit connections to writing center or writing studies organizations in a potential certification process. One respondent reported that "[t]he time and expense required did not offset the net gain of being certified especially outside of writing." Respondents noted that existing certification options "would create a lot of extra work for our tutors without adding a lot of value." In addition, "The certification was too labor intensive and didn't seem to be appropriate." Perhaps most importantly, one respondent noted that existing organizations did not understand writing center work.

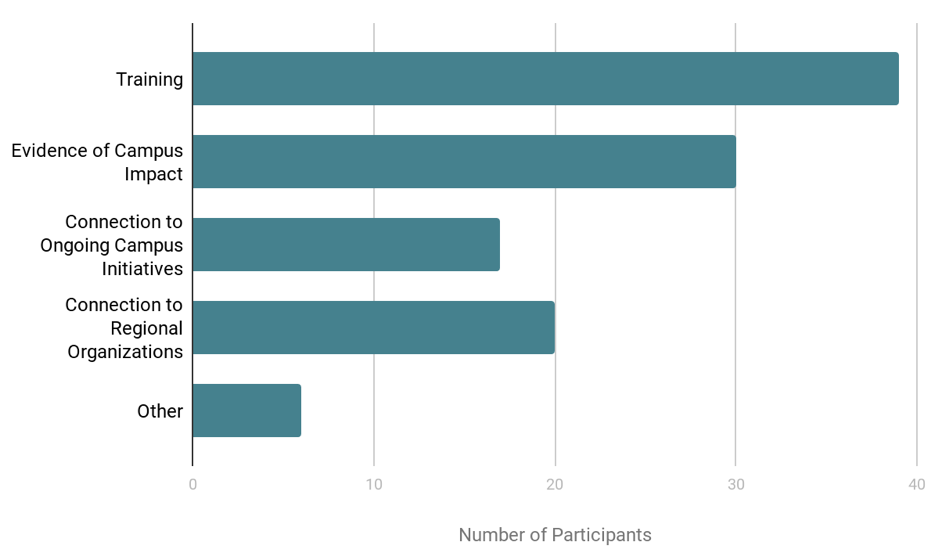

The fact that such a large percentage of our respondents had chosen not to follow through on certification suggested to us that if such effort were to be taken on, it would need to directly support intellectual development and day-to-day operations. The potential value that a certification program might add to tutor education was a priority among respondents; specifically, 97.5% (39 participants) listed tutor education or training as their top priority for certification and 75% (30 participants) responded with evidence of campus impact (Figure 1). In short, to be effective and valuable, certification programs must address and integrate the beliefs and nuances of writing centers.

|

| Figure 1. 2017 SWCA Certification Survey results for the question "What elements of writing center life or practice do you think should be valued in the certification process?" |

SWCA representatives have ensured that resources are available to support the growth and development of writing centers, students, and future leaders. It seems only fitting that the organization leverage its collective and growing knowledge to advance the field through a certification opportunity. Given our survey results as well as information gained from conversations with colleagues, it seems that writing centers are best served by those involved in the work at a day-to-day level. Processes—such as optional certification—developed outside of writing centers lack the direct connection and, ultimately, the ability to contribute to and develop writing center discourse.

SWCA representatives have ensured that resources are available to support the growth and development of writing centers, students, and future leaders. It seems only fitting that the organization leverage its collective and growing knowledge to advance the field through a certification opportunity. Given our survey results as well as information gained from conversations with colleagues, it seems that writing centers are best served by those involved in the work at a day-to-day level. Processes—such as optional certification—developed outside of writing centers lack the direct connection and, ultimately, the ability to contribute to and develop writing center discourse.

From Surveys to First Steps: Making Need a Reality

Before we discuss the results of our interview process, we offer the program we developed, about which we interviewed pilot participants. Our three-step certification program, which has been integrated into SWCA's framework, aligns with the priorities revealed in our survey. Our suggested model is not limited to this specific regional organization and can easily transfer to larger or smaller organizations. The application process involves multiple stages to ensure appropriate consideration by SWCA's Research & Development Committee, which reviews and archives submissions on the organization's webpage.

Step One: Material Submission

Applicants are first asked to gather materials that speak to their own writing center's work as well as the mission of their institution. Submission materials include:

- a letter of application

- a suggested two-page memorandum explaining institutional and writing center contexts

- a brief preview of supporting materials that include writing center tutor education documents: sample modules, syllabi, lists of readings, and other supplemental materials.

Applicants are encouraged to show how they make use of their regions' writing center resources (such as attending or presenting at conferences or statewide events, taking part in sponsored activities, and/or use of available supports). Furthermore, applicants offer a one-page description of their center's approach to tutoring and supporting writing. Finally, the director or program leader provides a current CV. These materials are received by the Chair of the Research & Development Committee and distributed to committee members for review.

Step Two: Committee Review with Rubric

The SWCA Research & Development Committee uses the SWCA IDEATE rubric to facilitate consistent consideration of applications while cultivating a transparent process of peer review that reflects the academic nature of the writing center field. The rubric establishes common goals for certification review while allowing the committee and applicants to consider ways in which their centers promote collaboration among tutors, intentional planning of tutor education (including currency of material, readings, and resources), and evidence of ongoing reflection to better serve the institution and its students.

Step Three: Committee Response

|

|---|

Figure 2. SWCA certification digital badge. |

A committee response and recommendation is sent to applicants, which includes a narrative of strengths and weaknesses of the application along with important feedback for implementation and success at that center. Importantly, the review process follows academic peer-review procedures by providing feedback, guidance, and resources in response to writing centers that are not successful in their certification application.

Certified centers receive an official, dated letter from the SWCA Research & Development Committee Chair congratulating the writing center on its accomplishment. Following precedents established by the National Association of Communication Centers (NACC), certified programs are not required to update their status unless prompted by their academic institutions. The organization also issues an official, dated certificate for the institution. Certified centers receive recognition in the SWCA conference program and at the award ceremony each year. Finally, certified centers are listed on the SWCA website and issued an electronic SWCA-certified center badge (Figure 2) that, as Tammy S. Conard-Salvo and John P. Bomkamp explain, allows for display of achievements (5) for their website.2

Pilot Interviews: Two Accounts of Certification

The certification process was based on feedback from pilot participants and is meant to be transparent for directors, tutors, and college administrators alike. After submitting their certification materials, two participants were invited to consider and respond to three broad questions about their experience in the application process. We hoped that such interviews would give the Research & Development Committee some tools to improve future certification cycles, while allowing current applications an opportunity to shape the future of this research. These interviews also gave applicants another opportunity to consider their programs within their respective campus missions and institutional contexts. The interviews provided a window into the granular level of detail and nuance involved. The interviews also provided insight into the following questions:

- Which parts of the certification process were the most meaningful to you and the community members in your writing center (staff and other professionals)?

- The history of the conversation within the writing center community about certification is rhetorical, about how people notice it and about how people perceive it. In what ways do you anticipate this certification (and process) will make a difference at your institution?

- Did the certification experience give you an opportunity to reconsider practices (including but not limited to educational development of staff, spatial design, programmatic structure, etc.)? If so, how?

Participants' answers to these questions offer several insights into the importance of writing center certification and tutor education.

Program A

Program A is at a public, two-year university of 3,621 students. In this writing center, the director (Participant A) is the only full-time staff member, and the writing center is being built from the ground up. Currently, the writing center has funding for only one tutor (with no unpaid or volunteer tutors); however, the move from completing five tutoring sessions to 300 in one academic year indicates the need for more resources. The certification process helped the director continue to think through tutor education and how to engage various campus entities within tutor education. Participant A describes the certification process as highly valuable in building ethos for the writing center, building tutor education programming, and encouraging further reflection after the certification process.

The inclusion of an outside entity (SWCA) promotes and validates improvement and rigorous academic work within the context of the writing center. Participant A claims that, in her experience and in her writing center, the "[certification] shows the importance of training and teaching consultants or tutors" for both writing center staffers and outside constituents. Furthermore, the certification process allowed for Participant A to create a more in-depth, positive dynamic between the writing center and other campus programs.

In addition to sparking productive conversations across campus entities, participating in the certification process allowed Participant A to reflect on the writing center's developing tutor education program. Because Program A is situated within a two-year institution, as it grows, many tutors will be employed for only one semester. Therefore, Participant A reevaluated what each student needs for the specific semester, shifting this writing center's educational assessment approach from analyzing ongoing trends to targeted, case-by-case progress reports.

The reflection aspect of the certification process helped Participant A reevaluate the writing center at large, stating that she would not have been able to allocate the time to complete these tasks without the structure and motivation a certification process provides [sound clip]. Such reevaluation allowed Participant A to reconsider tutor training and the greater impact of tutor education [sound clip]. Throughout her reflection, Participant A explains the incredible value of this certification process because of the relatively new nature of her writing center—how the kairotic moment of a potential tutor education course and the establishment of cross-campus relationships allow for such certification steps and reflective thinking to be meaningful. That said, as shown below, certification can also be quite impactful for long-standing writing centers as well.

Program B

Program B is a private research university with a student enrollment of 24,148. With a staff comprised of 40-50 undergraduate and graduate tutors as well as 10-15 part-time professional tutors, this program has begun to branch out by transitioning from a college-specific program to one that serves the university at large. Like Participant A, Participant B found that the act of completing the certification process affirms the work completed within the writing center, both for themselves and their staff, and for other outside entities that collaborate with the writing center.

Program B operates in a university with several professional accreditations and certifications. Based on prior relationships and initiatives, Participant B believes completing the SWCA certification process will be appreciated by both writing center staffers and institutional educators and leaders [sound clip]. Participant B personally found great meaning in the compilation of the certification materials [sound clip].

As a seasoned writing center scholar and administrator, Participant B provided forward-thinking reflections and feedback on the certification process and materials provided by SWCA. This feedback was considered when revising materials for future applicants—specifically in the creation of rubrics that align with other higher education certification organizations. Although Participant A offered substantive, reflective feedback that helped us see the value of the current pilot, feedback from Participant B provided a clear direction for future certification processes, procedures, and materials.

Where We Go from Here

Writing centers considering certification have traditionally had to adopt already existing certification programs from related but somewhat distanced fields of study. Our survey, pilot process, and interview responses display an interest in a peer support and review system, but one that would be worth the effort and that would reflect familiar, field-specific values. Along with conferences, collaboratives, regional gatherings, and other events, certification allows program leaders to validate their efforts such as learning best practices or emerging approaches in other centers and employing them in ways that benefit their own centers. Scholars of rhetoric and writing have argued for the importance of organization-specific frameworks. For example, Randall McClure and James P. Purdy's recent collection employs the Association of College and Research Library (ACRL) Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education and the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing created by the Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA), the National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE), and the National Writing Project (NWP), in providing theoretical and practical ways to justify important program decisions and staff development; Cahill et al. also modify the eight habits of mind included in the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing to guide principles used to develop writing center tutors. In this collection, we find a similar call for the development of writing center frameworks specifically grounded in tutor education values and practices. Elisabeth Buck narrates the role that writing center values and practices play in mitigating local contexts and in developing a tutor education course that is connected to the work of writing centers. Furthermore, Julia Bleakney examines ongoing tutor education programs and explores the value of related writing center education models. These authors, amongst others, argue that writing centers are stronger when driven by community participants—in this case, writing center scholars who know the day-to-day challenges of our work. Certification, when done well, supports and enriches tutor development.

Writing centers considering certification have traditionally had to adopt already existing certification programs from related but somewhat distanced fields of study. Our survey, pilot process, and interview responses display an interest in a peer support and review system, but one that would be worth the effort and that would reflect familiar, field-specific values. Along with conferences, collaboratives, regional gatherings, and other events, certification allows program leaders to validate their efforts such as learning best practices or emerging approaches in other centers and employing them in ways that benefit their own centers. Scholars of rhetoric and writing have argued for the importance of organization-specific frameworks. For example, Randall McClure and James P. Purdy's recent collection employs the Association of College and Research Library (ACRL) Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education and the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing created by the Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA), the National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE), and the National Writing Project (NWP), in providing theoretical and practical ways to justify important program decisions and staff development; Cahill et al. also modify the eight habits of mind included in the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing to guide principles used to develop writing center tutors. In this collection, we find a similar call for the development of writing center frameworks specifically grounded in tutor education values and practices. Elisabeth Buck narrates the role that writing center values and practices play in mitigating local contexts and in developing a tutor education course that is connected to the work of writing centers. Furthermore, Julia Bleakney examines ongoing tutor education programs and explores the value of related writing center education models. These authors, amongst others, argue that writing centers are stronger when driven by community participants—in this case, writing center scholars who know the day-to-day challenges of our work. Certification, when done well, supports and enriches tutor development.

As our Participant B indicates, certification guidelines should read like field-specific standards rather than open-ended questions or prompts from related fields. This shift in language and approach could further promote the high level of accomplishment achieved through certification, which is consistent with the feedback from Program B. Additionally, the language used in the certification should prompt reflection from participants, beyond calling for applicants to assemble materials [sound clip]. Thus, our certification-design process used participant feedback to help us revise a set of guiding IDEATE (Ideas for Developing Excellence Among Tutor Educators) documents to support the planning, preparation, writing, and assembly process of certification-related materials.

The IDEATE documents consist of the IDEATE Planning Guide, as centers consider the design process of materials that can support their center's planning process, and IDEATE Certification Recommendations, a set of broad-based and widely applicable best practices for writing centers to consider, and the SWCA IDEATE Rubric, to support centers as they prepare certification applications.

A certification process is a major undertaking, even for long-standing organizations. While we do not claim that any certification would solve all challenges facing writing centers, the steps that might best represent the significance and complexity of this work would, ideally, be built out of current writing center practices. A writing center certification program should acknowledge evidence that programs offer a writing-based, scalable design built upon highly nuanced rhetorical and disciplinary complexities familiar to those in charge of writing support.

As with all good writing center initiatives, our collaborative work is fueled by feedback. Our ongoing study and process focus on gathering more evidence and input concerning the value-added nature of regional organizations through interviews with selected writing center professionals at a variety of colleges and with various levels of experience via future conferences such as SWCA. We also plan to invite additional SWCA institutions to consider pursuing certification, responding to cultural shifts in writing centers through thoughtful future adaptations. We hope that writing centers outside of SWCA might consider using the tools, such as the IDEATE documents, we developed for program leaders' reflection and programmatic development.

NOTES

1 (back to text) We recognize that the terms "accreditation" and "certification" are often used interchangeably. For the purposes of this article, we use the term "certification" to reflect the nature of the regional organizations we discuss, and how such organizations are different from the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools or other official "accrediting" bodies. Furthermore, we recognize the potential political problems in having "unaccredited" writing centers.

2 (back to text) We recognize that Conard-Salvo and Bomkamp are speaking of badges for individual staffers, rather than programs.

Works Cited

Bleakney, Julia. "Ongoing Writing Tutor Education: Models and Practices." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Bleakney.html.

Buck, Elisabeth H. "From CRLA to For-Credit Course: The New Director's Guide to Assessing Tutor Education." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Buck.html.

Cahill, Lisa, et al. "Developing and Implementing Core Principles for Tutor Education: Administrative Goals and Tutor Perspectives." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Cahilletal.html.

Carpenter, Russell, Scott Whiddon, and Courtnie Morin. "'For Writing Centers, By Writing Centers': A New Model for Certification via Regional Organizations." WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 42, no. 1-2, 2017, pp. 2-9.

Conard-Salvo, Tammy S., and John P. Bomkamp. "Public Documentation of Tutors' Work: Digital Badges in the Writing Center." WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 40, no. 1-2, 2015, pp. 4-11.

Devet, Bonnie. "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Certifying a Tutoring Program through

CRLA." The Writing Center Director's Resource Book, edited by Christina Murphy and Byron Stay, Laurence Erlbaum, 2006, pp. 331-38.

Devet, Bonnie, and Kristen Gaetke. "Three Organizations for Certifying a Writing Lab." Writing

Lab Newsletter, vol. 31 no. 7, 2007, pp. 7-12.

Law, Joe. "Accreditation and the Writing Center: A Proposal for Action." Writing Center

Perspectives, edited by Byron L. Stay, Christina Murphy, and Eric H. Hobson, NWCA, 1995, pp. 155-161.

McClure, Randall, and James P. Purdy, editors. The Future Scholar: Researching & Teaching

the Frameworks for Writing & Information Literacy. Information Today Inc., 2016.

Morin, Courtnie, and Jessica Ralston. "Developing Excellence in Consultant Knowledge: A

Multimodal Training Plan." Southeastern Writing Center Association Conference,

16 February 2017, University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS. Session E-5.

Ralston, Jessica, and Courtnie Morin. "Enhancing Training through Multimodality: An Innovative Student Learning Platform." Innovations in Teaching and Learning: Proceedings from the 2017 Pedagogicon, edited by Russell Carpenter, Charlie Sweet, Hal Blythe, Matthew Winslow, and Shirley O'Brien, New Forums Press, 2017. pp. 83-88.

Simon, Julie. "'Tutorizing' Certification Programs." Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 33, no. 5,

2009, pp. 1-5.

Simpson, Jeanne, and Barry Maid. "Lining Up Ducks or Herding Cats? The Politics of Writing Center Accreditation." The Politics of Writing Centers, edited by Jane Nelson and Kathy Evertz, Heinemann Boynton/Cook, 2001, pp.121-32.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the excellent work in the development of resources to support the certification process by Lucas Green, Graduate Assistant in the Department of English & Theatre at Eastern Kentucky University and Research and Assessment Graduate Assistant in the Noel Studio for Academic Creativity, and the badging process by Leslie Williams, an undergraduate student in the Noel Studio for Academic Creativity. In addition, we wish to express our sincere appreciation to the two centers that participated in the pilot certification program and offered substantial feedback during the reflection process. We also express our gratitude to our institutions, staff members, and university leaders for the commitment to continued enhancement of writing center research and development. Finally, thank you to SWCA for allowing us to take on this important work.

BIOS

Russell Carpenter, Ph.D., is Executive Director of the Noel Studio for Academic Creativity and Associate Professor of English at Eastern Kentucky University. He is editor of the Journal of Faculty Development. Recent books include Sustainable Learning Spaces and Writing Studio Pedagogy.

Scott Whiddon, Ph.D., is director of both the Writing Center (TUWC) and the Writing, Rhetoric, and Communication program at Transylvania University in Lexington, KY. TUWC was a recent recipient of the Martinson Award for Excellence in Small Liberal Arts College Writing Program Administration. Scott has recent work in WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, and Southern Discourse in the Center.

Courtnie Morin, M.A., is an adjunct instructor for both Eastern Kentucky University and the University of Kentucky where she teaches a variety of rhetoric and first-year composition courses. She is also an instructor for the Applied Creative Thinking program that is housed within the Noel Studio for Academic Creativity at EKU. Courtnie's recent work can be found in WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, and the Journal of Faculty Development.