Justice for All: The Womanist Labor Rhetoric of Nannie Helen Burroughs

Justice for All: The Womanist Labor Rhetoric of Nannie Helen Burroughs

Peitho Volume 23 Issue 2 Winter/Spring 2021

Author(s): Veronica Popp and Danielle Phillips-Cunningham

Veronica Popp has a Master’s in Creative Writing from Aberystwyth University and a Master’s in English in Literary Studies from Western Illinois University. She is currently a PhD Candidate in Rhetoric with a minor in Multicultural Women’s and Gender studies at Texas Woman’s University. Popp has been published in Still Point Arts Quarterly, Gender Forum, and The Last Line. Her creative dissertation, Sick, was longlisted for the New Welsh Review Writing Awards 2017 AmeriCymru Prize for the Novella. She is the Graduate Research Assistant for Jane Nelson Institute for Women’s Leadership and Center for Women in Politics and Public Policy, Suffrage in Texas Expanded (SITE). Popp is acting chair for the Higher Education Profession Part-Time and Contingent Faculty Issues Committee of the Modern Language Association. Alongside her academic work, Popp worked as an organizer for the Chicago Metro Project in higher education constituencies at DePaul University, University of Chicago, and Northwestern University. Popp is currently an Instructor of English at North Central Texas College.

Danielle Phillips-Cunningham is Director of the Multicultural Women’s and Gender Studies Program at Texas Woman’s University where she teaches courses about women’s migrations and labors and feminist/womanist theories. Her book “Putting Their Hands on Race: Irish Immigrant and Southern Black Domestic Workers (Rutgers University Press, December 2019),” offers a transdisciplinary and comparative labor history of 19th and early 20th century Irish immigrant and US Black migrant domestic workers in US northeastern cities. Drawing on a range of archival sources from the United States and Ireland, this intersectional study explores how these women were significant to the racial labor and citizenship politics of their time.

Abstract: We argue that Nannie Helen Burroughs (1870-1961), usually interpreted as purely a missionary and remedial educator, was in fact also a significant labor leader and rhetorican. This argument is significant because it challenges gendered and classed constructions of history and rhetoric that render invisible the work women like Burroughs did during nadir. She believed a women’s labor collective (womanist principle of solidarity) would lead to social, political, and economic rights for Black women, which would result in liberation from racial, class and gender inequities for the entire Black community. We examine how Burroughs developed and employed her audacious, progressive, and forward-thinking labor rhetoric through an analysis of three major texts: “The Colored Woman and Her Relations to the Domestic Service Problem” (1902), “Divide Vote or Go to Socialists” (1919) and “My Dear Friend” (1921). We also argue that her womanist labor rhetoric led to the formation of a historic labor union for African American domestic workers in 1921, the National Association of Wage Earners (NAWE). We intend for our examination of her writings to commence rather than end a discussion about who Burroughs was as a labor organizer and rhetorician. She sought to liberate black women from penury by offering a broad educational focus on labor to her students and the larger black community, instilling racial pride in her students, and placing these women into positions of stable employment through a womanist labor platform.

Tags: feminism, labor, organizing, Race, womanismWe are not less honorable if we are servants.

Fidelity to duty rather than the grade of one’s occupation is the true measure of characterNannie Helen Burroughs (“The Colored Woman and Her Relations to the Domestic Service Problem” 326)

African American clubwoman and educator Nannie Helen Burroughs (1879-1961) was a significant labor leader and rhetorician. Burroughs was at the beginning of her labor organizing career when she delivered her speech “The Colored Woman and Her Relations to the Domestic Service Problem” in Atlanta, Georgia in 1902.1 She spoke to the Negro Young People’s Christian Congress, an audience of mainly Black educators, about domestic service reform and her plans to fight for equal pay and respect for African American2 women laborers. We argue that following her speech, Burroughs developed and employed a labor rhetoric that led to the formation of a historic labor union for African American domestic workers in 1921, the National Association of Wage Earners (NAWE).

Burroughs’s rhetoric was both unique and effective. It was based on womanist inclusivity and solidarity and ignited an organization that expanded the traditional labor union organizing model in significant ways. According to the premier womanist scholar Layli Maparyan (formerly Layli Phillips), womanism is a “social change perspective that is rooted in Black women’s and other women of color’s everyday experiences and everyday methods of problem solving in everyday spaces” (xx). Grassroots organizers have employed womanist values of egalitarianism to fight against injustices that impact disenfranchised communities. In this article, we trace how Burroughs put her womanist labor rhetoric into action to establish the first African American women’s labor union in the United States in her effort to dismantle systemic racial, class, and gender inequalities that disproportionately impacted African American women in the US labor economy.

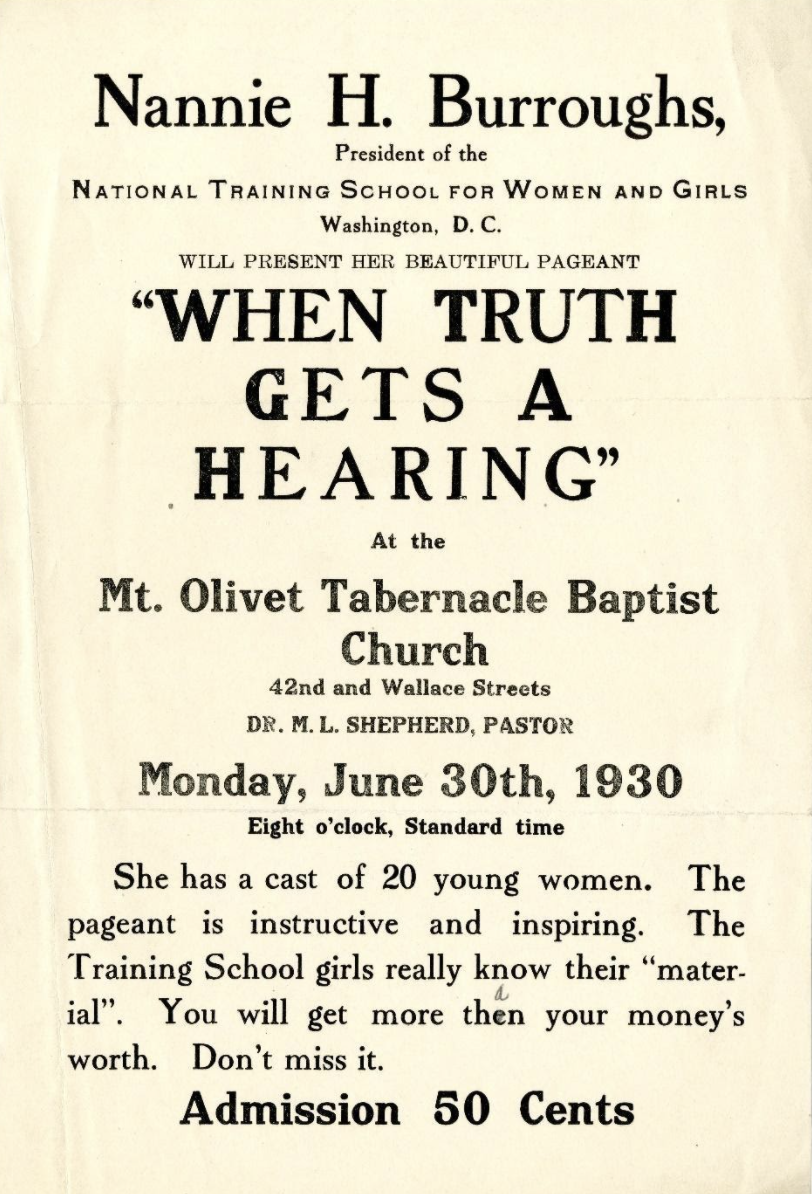

Burroughs established the National Training School for Women and Girls (NTS) in 1909, with the support of the Woman’s Convention of the National Baptist Convention (NBC), to provide a vocational and classical education for Black women so that they could pursue whatever career they desired. With a keen sense of the racial, class, and gender inequities in the labor sector, Burroughs knew that Black girls who entered her school would most easily find employment as maids no matter the level and quality of education that they received. Her curriculum, nonetheless, reflected her ambitious goal of charting pathways for Black women to enter professions that had been designated for European immigrant and native-born white women. Her school offered courses in domestic science, dressmaking, tailoring, music, language, Black history, poultry raising, missionary and social service work (“Training school to open”). Burroughs insisted on the importance of establishing a course of education to elevate the status of domestic work even in her earliest years of serving as secretary of the Woman’s Convention in Kentucky. Burroughs’s largest project, however, was elevating Black women’s status in the labor sector by professionalizing and dignifying domestic work through labor unionization and the domestic science curriculum at her school.

Her labor rhetoric complicated the tradition of unionization in two unique and important ways. Firstly, she asserted the need for federal union rights for all laborers. It was not until the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 that the US government created a standard of collective bargaining to prevent industrial workers (barring both agricultural and domestic) from being exploited on the job (“National Labor Relations Act”). The NAWE was thereby fourteen years ahead of its time. Secondly, there were no unions available for Black women in the early twentieth century, nor had there been any prior. While Burroughs did not reach her unionization benchmark, she struck a match for a national Black women’s labor movement through her strategic writings that inspired her organizing one of the largest untapped labor markets.

To be clear, historians have contested the idea that the NAWE (1921) was a labor union because it was not recognized as such by the federal government.3 We argue it is important to read the term “union” rhetorically through both Burroughs’s writings and practices to develop a new framework for making visible Black women’s labor organizing that is rendered invisible by the racial and gender politics of the archive and labor union practices. Labor organizations and unions such as the AFL-CIO, primarily led by white male industrial workers, refused to integrate African American women’s national labor agenda into their own labor causes. A textual analysis of Burroughs’s writings charts her historic labor project beyond the politics of race and gender that shape historical memory, and creates a pathway for recognizing the NAWE as a labor union. We argue that the NAWE operated like a union, as many organizations do, long before accorded legal rights.

The womanist labor rhetoric of Burroughs was based on a philosophy that working-class Black women have power and deserve respect in their workplaces in the form of living wages and safe working conditions to be attained through member driven unionization. This rhetoric includes the development of a class consciousness that demands a critical analysis of wealth, poverty and social mobility. In this article, we trace how Burroughs put her rhetoric into praxis through her writing and grassroots organizing to form the first national Black women’s labor union of the twentieth century. The texts feature three main themes Burroughs addressed throughout her labor rhetoric. She believed a women’s labor collective (womanist principle of solidarity) would lead to social, political, and economic rights for Black women resulting in liberation from racial, class and gender inequities for the entire Black community. We examine how Burroughs employed her audacious, progressive, and forward-thinking labor rhetoric through an analysis of three major texts: “The Colored Woman and Her Relations to the Domestic Service Problem” (1902), “Divide Vote or Go to Socialists” (1919) and “My Dear Friend” (1921).

There is still more work to be done to unveil the significance of the NAWE and Burroughs’s rhetoric for labor organizing today. The labor rhetoric of Nannie Helen Burroughs led to organizing workers not based on status, but within the same shared goal of justice for all. The project of unveiling Burroughs’s shadowed legacy of unionization has its challenges. In addition to the limitations of the archive, some of the NAWE records were destroyed due to a fire at its headquarters in 1926. Despite these challenges, we see Burroughs’s writings as providing a critical lens into the significant history of the organization. Her overarching goal was to address the struggles of Black women domestic workers in ways that would liberate the entire Black community from social, political, and economic oppression.

The Woman’s Words: Burroughs’s Womanist Principles

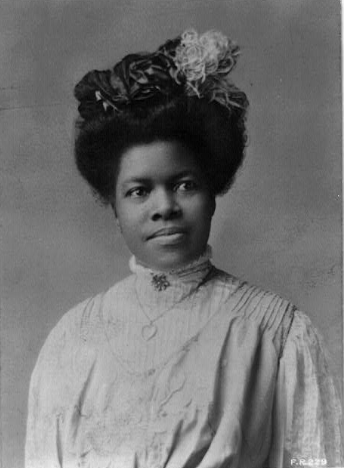

Fig. 1. Photograph of Nannie Helen Burroughs circa 1900 and 1920. © Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Burroughs recognized the need for a labor organization that firmly advocated for working-class Black women in an era of racial segregation and the absence of laws to protect Black women from labor exploitation. As a daughter and granddaughter of domestic workers,4 professionalizing domestic work and instilling pride in work was crucial to Burroughs. In her speech,“The Colored Woman and her Relations to the Domestic Service Problem,” Burroughs employed womanist principles to inspire the audience to recognize the importance of domestic service reform, “Negro women can bring dignity to service life, respect and trust to themselves and honor to the race” (329). The changes Burroughs sought were guided on the principle that African American women deserved fairness and equality at work. Her address to the audience was guided by her womanist belief that women were the social and economic anchors of the community because domestic workers were a large workforce in the Black community and were the pillars of community organizations, schools, and churches. Women (working in solidarity with men) were thereby most capable of uplifting the race and guiding the Black community to empowerment.

Burroughs began her speech by deconstructing the negative stigma associated with domestic service, making the argument that domestic workers and their labors were especially critical to the progress of the Black race. According to Burroughs, the labor issues confronting domestic workers were critical to all African Americans regardless of gender, occupation or class status, and those issues could be remedied through domestic science education. As she proclaimed, “The training of Negro women is absolutely necessary, not only for their own salvation and the salvation of the race, but because the hour in which we live demands it” (Burroughs 325). Her strategy of foregrounding the importance of domestic workers in a Black liberation movement was to deconstruct the negative connotations associated with domestic service. Household employment was a labor niche that carried the racial stigma of slavery, even in some early twentieth century Black communities. She considered it significant to dismantle this stigma in order to achieve her goal of galvanizing community support for a labor movement that centered domestic workers. In her words, “When the nobility of labor is magnified, and those who do labor are respected more because of their real worth to the race, we will find a lot less number trying to escape the brand servant girl” (Burroughs 326). She offered three concrete solutions for elevating the status of domestic work in the eyes of employers: domestic science training, fair wages, and vacation time (Burroughs 329).

Burroughs put the womanist principle of community solidarity into practice not only in the speech, but through her strategic delivery of it. Her decision to travel, deliver and publish “The Colored Woman and her Relations to the Domestic Service Problem” in Atlanta, Georgia, with the Young People’s Christian Congress, reflected her belief that domestic service reform impacted a national audience, even future generational leaders. The more African Americans who did not work in household employment were educated about domestic workers’ struggles, the closer the entire community would come to forming a strong moral and political alliance across class lines for Black liberation. The Congress, speech and eventual publication share the same vision of timeliness: the question of African Americans’ freedom from the lingering chains of both slavery and Jim and Jane Crow segregation had to be answered to achieve justice for all. Burroughs traveled often, spoke at meetings, and published with the intention to reach a national Black audience and convince them to join her in fighting for justice for all through labor rights for Black women.

“We have lived on promises”: Towards a More Radical Womanist Labor Vision

(Burroughs, “Divide the Vote or Go to Socialists”)

Burroughs’s polemic 1919 letter to the Baltimore African American editor entitled “Divide Vote or Go to Socialists” was one of the most radical articulations of her labor rhetoric.5 While Burroughs could not legally vote (Black women in DC would be disenfranchised past 1920), by articulating that she had a vote, she demonstrated the political significance of Black women’s labor at the ballot box. Burroughs vowed to educate Black people, become more politically active, and work with Socialists to create a more just future for African Americans. She claimed that if the major political parties continued paying lip service then joining the Socialist party was the only option for African Americans “Until the two great political parties… declare themselves on the Suffrage, Labor and Lynching questions, the Negro should go to the Socialist party that has already declared itself for exact justice and equality and opportunity for all” (Burroughs, “Divide Vote or Go to Socialists”). Burroughs publicly exposed both the Republican and Democratic parties for their failure to fully address three key issues to African Americans: labor exploitation, lynching, and discrimination against women, citing the power of the African American female vote.

As she declared to the paper’s African American readership: “We are going to stand for anything that is 100% American and oppose everything that is less” (Burroughs, “Divide Vote or Go to Socialist”). Burroughs’s urging African Americans to leave the party that liberated them from the institution of slavery (because it no longer served them politically) was an expansion of her other political work, which suggested the socio-political unity of Blacks based on Baptist principals of conservative fellowship. According to her, political parties had not taken Black economic interests seriously even though they relied on their votes. Therefore, Burroughs saw socialism as the salvation for African Americans because of its emphasis on equality in the labor economy. “Divide the Vote or Go to the Socialists” is where Burroughs demonstrated her radical ideas prior to her work at the NAWE. If whites were not going to join in solidarity for African American liberation, then African Americans would have to seek their own practical and hands-on solutions.

During the same year that “Divide Vote or Go to Socialists” was published, Burroughs and her colleagues, Mary Church Terrell and Elizabeth Haynes Ross, attempted to organize with the National Trade Union League of America at the inaugural International Congress of Working Women (ICWW) meeting to forge a labor alliance between Black and white women laborers. They discovered that white labor organizations supporting socialist ideals lacked an analysis of class inequalities at the intersections of race and gender. The ICWW was uninterested in taking up the specific concerns of working-class Black women and they declined the opportunity to create a cross-racial partnership with them (“First Convention of International Conference of Working Women”).

The ICWW meeting convened in Washington D.C with two hundred women in attendance, primarily white-Europeans and white Americans, to discuss strategies for combating the exploitation of women laborers across the world. Burroughs and her colleagues believed that this mass convening of working women in Washington D.C. was a critical opportunity for Black women to develop international alliances with white women labor organizations. They authored a petition including statistics and a detailed analysis of the labor exploitation of Black women laborers in the US economy, primarily highlighting the working conditions of Black domestic workers, “We, a group of Negro women, representing those two millions of Negro woman wage-earners, respectfully ask for your active cooperation in organizing the Negro women workers of the United States into unions…” (“First Convention of International Conference of Working Women”). The ICWW leaders rebuffed the petition. As labor historian Lara Vapnek argued, the ICWW prioritized their class and racial alliances rather than gender alliances by not forming a partnership with African American women (Vapnek 166). The ICWW proceeded with an international conference without a focus on equal labor rights for women of all races and ignoring the working conditions of African American women detailed in the petition. Afterwards, Burroughs immediately began planning a labor union for Black women because no white labor organization in the early twentieth century was willing to join her cause.

NAWE’s Inception: “The hour has come for colored women in America to get together”

(Burroughs, “My Dear Friend”)

After failed attempts to unionize with white women, Burroughs formed a labor union for all Black women, with an emphasis on achieving domestic workers’ rights and the highest bargaining chip of all: a walk out by a single union. A strike is a collective decision as a last resort when all methods of collective bargaining at the table have been employed by the membership and are regulated by the NLRB (“The Right to Strike”). According to the NAWE Constitution, members had the right to strike if they were not granted stable employment, living wages, vacation time, death benefits and safe working conditions (“Nannie Helen Burroughs Papers”). Her call for a strike was especially daring because strikes or work stoppages provoke fear in employers who misunderstand the purpose of strikes in a labor movement, which is why strikes within floor to ceiling unions are uncommon.6 It was a bold strategy for African American domestic workers who could have easily been arrested for not showing up to work because of Jim and Jane Crow laws. By calling for solidarity and cooperation of all Black workers across gender and occupation, Burroughs was ahead of her time. Coalition politics rooted in solidarity were just beginning and weakened by the Taft Hartley Act of 1947, which federally banned solidarity-based strikes (“Taft Hartley Act of 1947”). Her approach was effective in creating not only a Black women’s labor union, but one that expanded the traditional labor union organizing model through coalition. Rather than solely galvanizing workers within the same occupation for labor rights, Burroughs and the NAWE organizers recruited workers from a variety of working-class and middle-class occupations to advocate for domestic service reform.

Burroughs expressed her deepened womanist commitment to creating a Black women’s labor collective in her March 21, 1921, open letter entitled “My Dear Friend” published in the Washington Bee, an African American newspaper based in Washington D.C. that had covered Burroughs’s activist work since her teen years. The call for NAWE membership was a national woman centered communal one of inclusivity in the United States from every field. Burroughs took a personable approach to inspiring audiences to come together for a common purpose by beginning the letter in first person. She reminded the readership of their shared union vision, exigency for a labor union by stating: “We want to enlist 10,000 women in the National Association of Wage Earners, who in turn will enlist another 10,000. We want women from every walk of life” (Burroughs, “My Dear Friend”). The use of armed service terminology alongside the specific numbers indicates her determination that this is not an optional call; it is a call to defend the rights of Black women everywhere.

Burroughs saw herself as part of the women’s collective that she sought to create because never considered herself divided from working-class Black women. In the letter, Burroughs tied her belief in the power of women’s labor organizing to her racial uplift goals. According to her, the NAWE could improve the working and living conditions of the entire Black community by achieving nine goals for domestic workers (enclosed at the bottom of the letter). As Burroughs detailed, NAWE organizers collected dues; documented grievances; trained and placed employees; advocated for labor rights legislation; provided safe housing; started a uniform co-operative run for and by Black women; and opened a local office for community events and meetings (“My Dear Friend”).

Within her letter, Burroughs simultaneously subverted and reasserted the classist and elitist philosophy of racial uplift. She argued both middle class and working-class women could uplift the Black race together through the womanist principle of women’s solidarity. According to Burroughs, middle-class and working-class Black women were social equals who contributed tremendous value to the Black women’s labor movement. She declared, “The women who are backing this organization are not misfits and failures, but are successful in the particular lines” (“My Dear Friend.”) In this sentence, she reframes the divisive language used to create class boundaries between Black women along employment lines. She called for both working-class and middle-class women to join the NAWE. “We want women from every walk of life– cooks and clerks, field hands and parlor maids, teachers and laundresses, dressmakers and charwomen, beauty culturists and factory workers, boarding housekeepers and training nurses business women and the army of unclassified toilers North, South, East and West” (Burroughs, “My Dear Friend”). Through her roll call of women from a variety of professions and regions, Burroughs made it clear that her purpose was to invite all women to the bargaining table.

Black women laborers who had a deep understanding of achieving solidarity through racial pride and empowerment were central to Burroughs’s vision for racial uplift and community empowerment. She also believed that Black women of all creeds, colors, and levels of education could succeed in achieving labor rights without the full acceptance of white society. Thus, the fate of the Black community was in the hands of Black laboring women, and not the white community. The ethos underlying her push for Black women’s solidarity across class, region, and occupation was like that of formally recognized labor unions: an injury to one is an injury to all. At the end of the “My Dear Friend” letter, Burroughs reinforces and inserts herself into the power behind Black women’s collective solidarity organizing when she states that the women of the NAWE move in unison, that “they all want to climb together” (“My Dear Friend”). In closing, Burroughs ends with a note on her faith and belief in the Black community to recruit women workers to the NAWE. “They need your help, and they believe they are going to get it” (“My Dear Friend”). While a distinctly women’s labor union, the NAWE also welcomed Black male allies. Her closing is non-gendered, thereby, making sure that she employed the womanist principle of solidarity through welcoming the participation of both women and men in the membership drive. The expansive gender membership of the NAWE, which included barbers, insurance agents, pastors, and male professors, suggests that Burroughs sought to build a mass labor movement across gender and class status among Black laborers in the private and public spheres (“Nannie Helen Burroughs Papers”).

Shortly after “My Dear Friend” was published, Burroughs spoke at the First Baptist Church of Richmond, Virginia, advertised as President of the NTS and NAWE, again proving her labor rhetoric had a national strategy (“Nannie Helen Burroughs at First Baptist Church”). Using both of her titles within the publication and no title of the speech itself, the author of the article documents Burroughs’s ethos within the lecture circuit as a community leader. Burroughs implemented womanist grassroots organizing principles within her own community of Washington D.C. first and moved outwards nationally to work towards her membership benchmarks by announcing the NAWE’s launch in three African American based publications. Burroughs nine points, located in the NAWE Constitution, were re-printed in 1924 by Competitor, Crisis and Opportunity, African American themed national publications released by Negro Press, National Association of Colored People (NAACP) and National Urban League (“Nannie Helen Burroughs Papers”). Her reasoning was to tie her national association headquarters to other national organizations of Black audiences to reach a diversity of backgrounds.

The inclusion and naming of both local and national community organizers such as Sadie T. Henson, Maggie L. Walker and Mary McLeod Bethune in the NAWE leadership publications was rhetorically strategic. Burroughs was interested in recruiting women from a wide range of Black organizations to join the NAWE, demonstrating her effective use of the womanist ethos of inclusivity and egalitarianism. Henson, community organizer and former truant officer in Washington D.C., is cited as the district president and Walker is cited as treasurer (“Home Plans to Train Colored Domestics: National Association Opens Model Headquarters on Rhode Island Avenue–Is Unionized by Women”; “Wage Earners”). Walker served as the treasurer of the NAWE and was the first Black woman president of a “penny” save bank (“Home Plans to Train Colored Domestics: National Association Opens Model Headquarters on Rhode Island Avenue–Is Unionized by Women”; “St. Luke Herald”). Walker advocated for mutual aid and death benefits for the sick and terminally ill through the Independent Order of St. Luke, influencing NAWE policies on death benefits. Like Burroughs, Bethune ran a school for Black women and girls in Florida. Both women believed education was tied to organizing Black women workers across the U.S.

The intention of the dual leadership of Burroughs and Bethune through these organizations was to unite working- and middle-class Black women for the purposes of national Black labor solidarity. This race and class-based organizing through the NAWE was an extension of Burroughs’s initial 1902 labor vision. Her friend and colleague Mary McLeod Bethune was an active collaborator in the NAWE tying broader unionization and education of Black workers to her own political work in the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). Despite the NACW’s role as an unbiased advocate, Bethune used her position as President of the NACW to support the NAWE. As she explained, “That we most heartily endorse the work of the NAACP, the National Urban League, the Commission on Interracial Co-operation, the National Wage Earners’ Association among Women, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and all National Organizations whose purpose is to uplift” (4). Bethune believed that the NAWE should be led by women in coalition with other Black male labor organizations such as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters united together with the shared goal of better working conditions for African Americans.

The coverage on Burroughs twice in The Connecticut Labor News (1921-1925) shows her labor rhetoric was effective, because it resonated even with the mainly white male union activist audience. Each piece paraphrases Burroughs’s nine points and states that her primary purpose for establishing the NAWE was to establish a living wage for three million Black women workers. “House Servants Organize Union for Own Protection” was published in March 1924 with a subheading “Open Headquarters in Washington and Elect Officers; May soon Apply for Charter in A.F.L.” The Connecticut Labor News acknowledges that Black women workers in the United States faced marginalization into lower paying positions, exploitation in their workplaces and that unionization was the way to produce good workers. Since the paper was produced by white union activists, they were surprised that wages were not the first of Burroughs’s nine points (“House Servants Organize Union for Own Protection”). The goal of good workers, stable and permanent employment with safe housing and fair pay were intertwined, reiterating that Burroughs believed the dignity of Black women workers was at the root of all her nine points. Burroughs stated:

Negro women wage earners are the only large unprotected labor group in America. Unorganized labor will be exploited and mistreated. An organized labor group gets fairer wages, better living conditions, greater respect and economic justice. Then, too, join a labor organization that functions properly, develops in the workers greater skill and general efficiency, pride of occupation and improvement in general conduct. The latter improvements are as important as the former considerations.

(“House Servants Organize Union for Own Protection”)

After failing to acquire a charter with the A.F.L. due to its sexist, racist and classist perspective on workers, and seeking the support of other Socialists sympathizers, Burroughs again spoke to The Connecticut Labor News in October 1924. In “Union for Negro Women Workers [sic] Gaining Ground” Burroughs takes ownership for the independence of the NAWE and how African American women are setting the example for broad-based unionization across the United States:

Our women have had no standing with the AFL or NWTU League. Nothing has been done to improve the conditions of the Negro working woman. We must therefore, paddle our own canoe. A few colored women some months ago discussed the situation seriously and decided not to stop until we have organized all Negro working women into a labor union. The NAWE Inc. is the outcome of this conference.

(“Union for Negro Women Workers [sic] Gaining Ground”)

The article ends by citing the NAWE’s gains of between five and ten thousand members (“Union for Negro Women Workers [sic] Gaining Ground”). Clearly, Burroughs was building membership of the NAWE through her broad-based publications not only with Black audiences. At the core of her publications was her labor rhetoric rooted in womanist solidarity and inclusivity for all workers. As she believed, until the most marginalized at the intersections of race, class and gender are free, no one is.

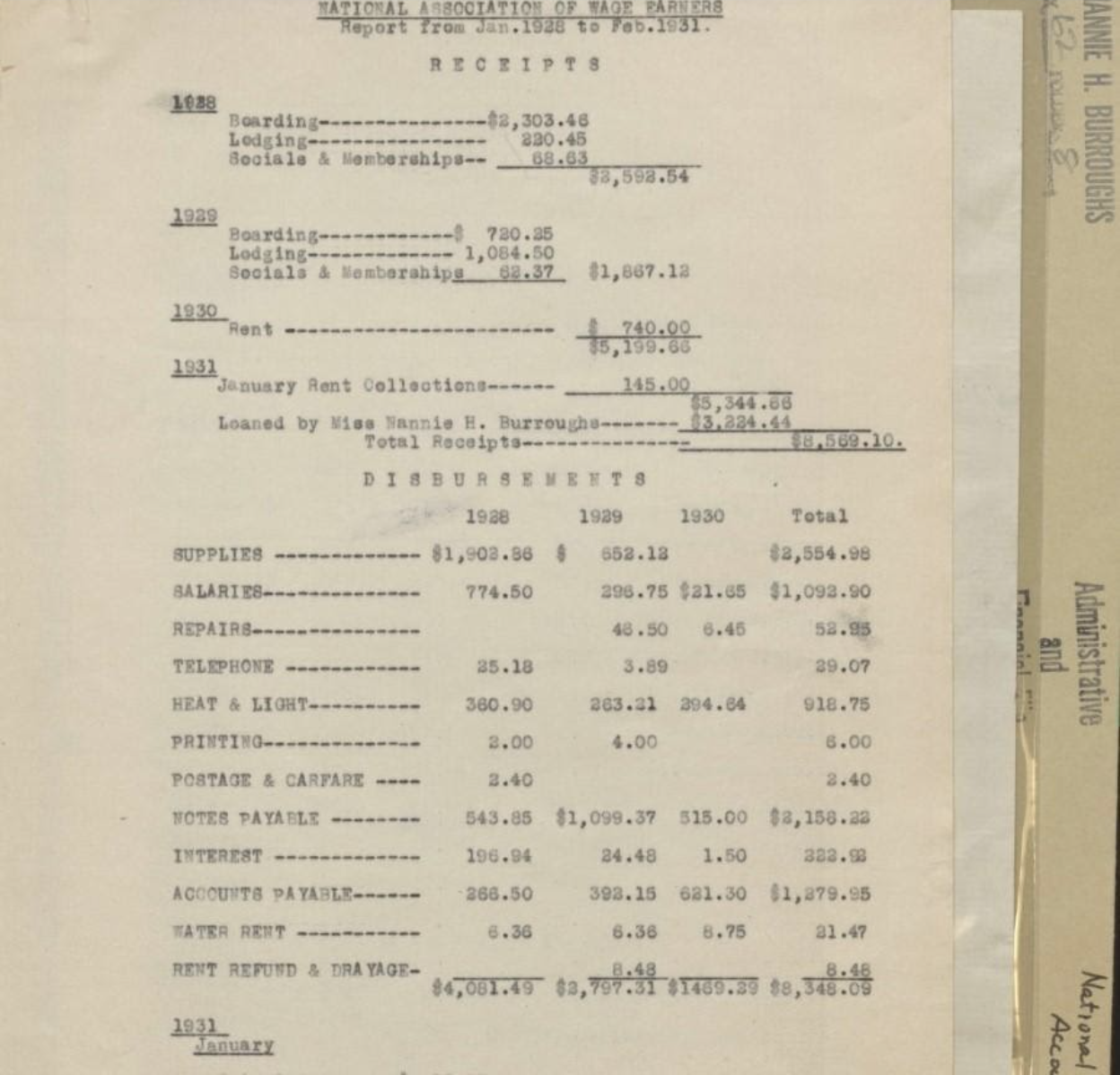

Fig. 2. Headquarters National Association of Wage Earners, 1115 Rhode Island Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C.© Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The NAWE flourished for a few more years, despite the Depression, debt, and a fire at the National Trade School for Women and Girls. Advertisements in the Evening Star for job placement (1924-1928) and accounting (1928-1931) shows the NAWE was still working for equity, seeking workers to represent and promoting their organizing efforts (see Appendix). The advertisements in the Evening Star targeted readers of the general D.C. newspaper rather than Black themed publications, because of the growing number of Black women laborers who were both seeking employment and housing in the city. Due to the constraints of the Depression, Burroughs founded another Black labor initiative called the Cooperative Industries in 1934. The industry was a mainly self-sustaining Black operation where workers accepted the communal and business responsibility for the welfare of their members by selling their profits and investing them back into their communities (“Cooperation Theory Tested in Colonies”).

While there are no publications directly quoting Burroughs about the cooperative, we see an expansion of her womanist labor rhetoric through her promotion of women’s entrepreneurship through a self-sustaining cooperative in the D.C. Black community. Many women who worked for the cooperative were unemployed domestic workers who wanted to labor outside of household employment. Workers at the cooperative provided services for Black and white D.C. communities as seamstresses, laundresses, bakers, cooks, nurses and clerks staffing a grocery store, with plans for a credit union, shoe repair shop and a broom factory (“Cooperation Theory Tested in Colonies”). Burroughs and the cooperative sought to control the process and products of their labor in a world that denied Black domestic workers the legal opportunities to file for unemployment benefits or Social Security.

Reviving Black Women’s Labor Organizing History

In 2020, Burroughs would be disappointed that her vision still has not fully come into fruition. Domestic workers are prevented from unionizing due to restrictive provisions in the NLRA stating that they do not qualify as employees and do not deserve federal labor rights.7 They were granted a provision under the 1976 Fair Labor Standards Act to receive a minimum wage,8 yet it did not hold employers legally responsible for paying them one (U.S. Congress, United States Code: Labor-Management Relations, 29 U.S.C. §§ 141-197). While we are a long way away from transforming household employment, Burroughs’s writings and labor organizing history are good places to start for envisioning and moving towards a collective women’s labor movement.

The NAWE effectively became a union even in defiance of a society that refused it the proper recognition. Burroughs and NAWE members organized along the same principles as a union, with the same foundational belief in the dignity of workers and their labor. As a co-founding organizer, Burroughs challenged dominant white hegemonic society through her writings and praxis. By advocating for full labor rights for Black women at work, Burroughs dispelled the stereotype of domestic workers as the lovingly submissive Mammy.9 She also created a labor organizing space for African American women in a society that was unwilling to accept them as skilled workers who deserved a living wage. Burroughs invoked and built an association that expressed the collective will of thousands of Black women and aspired to do so much more.

The labor organizing work of Burroughs has been buried in the annals of history10 due to racism, sexism and anti-Black labor organizing bias. The NAWE records should be more widely discussed and the organization’s history should be upheld as an example to strive towards rather than one to forget. The Black women workers in Washington D.C. (plus the male and female domestic and agricultural workers from the NAWE’s 23 other chapters across the United States) would encounter barriers to achieving full labor rights today. In fact, many low-wage women workers in labor unions in the twenty-first century still do not have the majority of Burroughs’s nine points outlined in her “My Dear Friend” letter.

Labor rights are human rights, and a labor rhetoric demands visibility. Burroughs’s vision for the NAWE, rooted in the womanist principles of community, equality, and solidarity, propelled the association’s leaders to draw from women’s extensive community networks to recruit a wide-ranging union membership. Burroughs lit the match for transformative labor organizing through her effective rhetoric that inspired people to find common ground across their class, age, and regional differences. It is now up to all laboring women and their allies to continue fanning that flame in the movement for labor rights.

Endnotes

- This speech was re-published by education and religious scholar Kelisha M. Graves in Nannie Helen Burroughs: A Documentary Portrait of an Early Civil Rights Pioneer, 1900–1959 (27-31). Graves’s purpose in re-publishing is to emphasize the timeliness of Burroughs and emphasize her contribution to theology.

- We alternate between Black and African American for stylistic variety.

- The National Labor Relations (or Wagner Act) was not passed until 1935 (“National Labor Relations Act”). For a union to achieve recognition a community of interest signs authorization cards indicating a showing of interest, holds an election and elects a union by the member majority before it gains both state and federal certification (“National Labor Relations Act”).

- Burroughs is cited as a janitor earlier in her career (Graves xxv).

- See Graves for an edited and updated version (97-98).

- Few strikes had occurred among domestic workers except for the 1881 washerwoman’s strike in Atlanta, Georgia. Tera Hunter argues “Washing Amazons and Organized Protests” Black washerwomen were ready to give up their family income for respect at work prioritizing solidarity over division through punishment of scabs and a targeted media strategy (75-78; 91).

- See Juan F. Perea, “The Echoes of Slavery: Recognizing the Racist Origins of the NLRA” for a reading on the discriminatory implications to the employee provision of the NLRA.

- Domestic workers grassroots organizing began in New York with the Domestic Worker Bill of Rights (“Department of Labor”). Similar bills to supply additional rights at work for domestic workers have passed in California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Oregon and Washington.

- See Hortense J. Spillers “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book” for a reading on African American women, language and tropes.

- There is evidence in Burroughs NAWE supplementary texts in Box 308 at the Library Congress: “My Dear Co-Worker” (1921) and “The Way to Make Money” (1921) of a deep organizing model (“Nannie Helen Burroughs Papers”). If Burroughs released these papers, there might have been a greater understanding of her labor rhetoric.

Appendix

Works Cited

- Anonymous. “A Union Would Enroll Colored Domestics.” The Washington Post. November 18, 1924.

- Bethune, Mary McLeod. “Program, Fifteenth Biennial Meeting. National Association of Colored Women,” August 1-6, 1926, The National Notes, vol. 28, no. 10, July-August 1926, pp. 1-4.

- Burroughs, Nannie. “Divide Vote or Go to Socialists.” August 22, 1919. ProQuest Historical Newspapers, The Baltimore Afro-American (1893-1988), p. 4.

- —. “The Colored Woman and Her Relation to the Domestic Problem.” The United Negro: his problems and his progress Containing the Addresses and Proceedings of The Negro Young People’s Christian Congress, edited by John W. E. Bowen and I. Garland Penn, Luther Publishing Company, Atlanta, 1902, pp. 324-329.

- Burroughs, Nannie Helen. “My Dear Friend.” The National Association of Wage Earners, Incorporated, Washington Tribune, March 26, 1921, pp.1-3.

- —. MS. “National Association of Wage Earners.” Nannie Helen Burroughs Papers. Box 308, Folder. Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

- —. “National Association of Wage Earners.” Nannie Helen Burroughs Papers. Box 309, Folder 1. Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

- Burroughs, Nannie Helen, and Kelisha B. Graves. Nannie Helen Burroughs: A Documentary Portrait of an Early Civil Rights Pioneer, 1900-1959. University of Notre Dame Press, 2019.

- Burroughs, Nannie Helen, and Elmer Anderson Carter, editor. “A Rather Inspiring Meeting.” Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life, vol. 1-2, 1969, p. 382-383. National Urban League.

- Department of Labor, New York State. Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights.

- “Employment Ads.” Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.), 24 Sept. 1928. Page 32. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- “First Convention of International Conference of Working Women.” Washington, D.C., International Federation of Working Women Records, Schlesinger Library, Folder 3.

- “Headquarters National Association of Wage Earners, Rhode Island Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C.” Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

- “Home Plans to Train Colored Domestics: National Association Opens Model Headquarters on Rhode Island Avenue–Is Unionized by Women.” The Washington Post. November 10, 1924.

- “House Servants Organize Union for Own Protection.” The Connecticut Labor News. (New Haven, Conn.), 29 March 1924. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- Hunter, Tera. To ‘Joy My Freedom’: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- “National Association of Wage Earners: Nannie Helen Burroughs.” Competitor. June 1921.

- National Labor Relations Board. “National Labor Relations Act.” NLRB.

- —. “The Right to Strike.” NLRB.

- —. “What We Do.” NLRB.

- “Nannie Helen Burroughs Papers.” The Library of Congress.

- Perea, Juan F. “The Echoes of Slavery: Recognizing the Racist Origins of the Agricultural and Domestic Worker Exclusion from the National Labor Relations Act.” Ohio State Law Journal, 2011. pp. 95-138.

- Phillips, Layli. The Womanist Reader. Routledge, 2006.

- Richmond Planet, vol. XLI, no. 26 (Richmond, Va.), 17 May 1924. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- “St. Luke Herald.” National Park Service, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site. vol. XXI, no. 37. 30, December 1922. MAWA 4482.

- “Training School to Open: Negro Women to be Taught to be Domestics.” Evening Star, vol. 137. (Washington, D.C.), 17 Oct. 1909. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- United States Code: Labor-Management Relations, 29 U.S.C. §§ 141-197. 1976. Periodical. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

- “U.S. Department of Labor.” Office of Labor-Management Standards (OLMS), U.S. Department of Labor.

- “Untitled.” Opportunity, vol. 2, no. 24, December 1924, p. 383. 1 page.

- Vapnek, Lara. “The 1919 International Congress of Working Women: Transnational Debates on the ‘Woman Worker.'” Journal of Women’s History, vol. 26 no. 1, 2014, pp. 160-184. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/jowh.2014.0015.

- “Wage Earners.” Washington Bee. April 7, 1917. vol. XXXVII, no. 45.

- Weinberg, Sylvia. “Cooperation Theory Tested in Colonies.” The Sunday Star, no. 1710 (Washington, D.C.), 26 Dec. 1937. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- “When Truth Gets a Hearing.” Ruth Wright Hayre Collection, Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection, 1930. Temple University Libraries.