Feminist Practices in Digital Humanities Research: Visualizing Women Physician’s Networks of Solidarity, Struggle and Exclusion

Feminist Practices in Digital Humanities Research: Visualizing Women Physician’s Networks of Solidarity, Struggle and Exclusion

Peitho Volume 22 Issue 2 Winter 2020

Author(s): Patricia Fancher, Gesa Kirsch, and Alison Williams

Patricia Fancher is a lecturer at the University of California, Santa Barbara where she teaches and researches digital media, technical rhetoric, and feminist rhetorics. Her research on gender and digital media has been published in Rhetoric Review, Present Tense, Composition Studies, Computers & Composition, Enculturation in addition to several edited collections. In addition to her research on digital media, she also designs and produces feminist digital scholarship, which can be found in the Fall 2015 and 2016 issues of Peitho. She is currently complete a book project entitled Embodying Computing, which locates a queer techne in the history of the invention of digital computing.

Gesa E. Kirsch is a Professor of English at Bentley University and served as the Thomas R. Watson Distinguished Visiting Professor at the University of Louisville in 2019. Her research focuses on feminist rhetorical studies, archival research, ethics and representation, and innovation and creativity studies. She has authored, coauthored, edited and co-edited nine books and numerous articles, including More than Gold in California: The Life and Work of Dr. Mary Bennett Ritter (2017, a critical edition of a historically significant memoir by an early woman physician), Feminist Rhetorical Practices: New Horizons for Rhetoric, Composition and Literacy Studies, co-authored with Jacqueline Jones Royster, winner of the Winifred Bruce Horner Outstanding Book Award, and Beyond the Archives: Research as a Lived Process, co-edited with Liz Rohan. She has won the Bentley Innovation in Teaching Award (twice) and the Mee Family Prize for a life-time of distinguished research, Bentley’s highest distinction. Her current research explores the rhetorical strategies, professional networks, and social activism of early twentieth-century women physicians.

Alison Williams is a lecturer at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her teaching and research centers on concepts of identity, new media composition, and feminist rhetorics. This article is her first scholarly publication, and her creative work has been published in World Literature Today, Poetry International, and Levure Litteraire, amongst others. Alison was the founding editor-in-chief of Chapman University’s graduate interdisciplinary journal, Anastamos. She is currently at work on a novel about women settling the American West in the late 19th century.

Abstract: We study the evolving community of early 20th century women physicians, their rhetorics of solidarity, and the limits of that solidarity, including racist exclusion. We developed methods that engage in intersectional feminist research via critical imagination and digital humanities methods. These methods include viewing community from a distance with social network analysis, which reveal communities of solidarity, struggle and exclusions; close reading, which highlights women in particular contexts; and critical imagination which allows reimagining the social network in a way that acknowledges the contributions of African American women physicians. We explore this archive as a representation of solidarity for white women physicians, while simultaneously demonstrating that this community created boundaries, set priorities, and reinforced racist exclusion.

Tags: 22-2, African American women physicians, archival research, critical imagination, digital humanities methods, distant reading, exclusion, feminist historiography, history of medicine, Intersectionality, professional networks of women, racism, social network analysis, solidarity, visualizations, white women physicians, Woman’s Medical JournalIntroduction

Feminist historiography of rhetoric has increasingly emphasized recovering not only individual women rhetors but also recovering the communities and collectives of women who work together (Gaillet and Gaillet; Gries and Brooke; Ryan, Myers and Jones). Following this momentum, our project studies a community of early 20th century women physicians and draws on the Woman’s Medical Journal (WMJ)—the only medical journal published by and for women physicians—as a primary source to study how women created community, shared resources, and collaborated across geographically distributed communities. Utilizing both digital humanities (DH) methods as well as critical imagination (Royster & Kirsch), we explore the ecology of this community, its evolution over time, and the rhetorical strategies that supported the building of community.

In particular, we pay attention to how women negotiated solidarity and inclusion, while remaining mindful of exclusions within this community. We ask: Community for whom? Solidarity for whom? From this archive we gain insights about community and collaboration, about the politics of in- and exclusion, and about the affordances and limitations of white feminist solidarity.

We began this feminist project because we admire how the editors of the WMJ deliberately set out to foster the community, collaboration, and professional networks of women. The journal published not only medical research, case studies, and treatment plans, but also notices, announcements, and listings of women physicians, personal and professional; women graduates of medical schools; opportunities for positions, fellowships, internships; advanced clinic training; and international travel. In short, the WMJ appears to have functioned as a print-based form of social media. We identified an opportunity to use DH methods to map key actors, institutions, and centers of activity (and power) to better understand this extensive influential social network platform of early women physicians.

Additionally, once we began closely studying the WMJ, the racist logics of the times quickly rose to our attention. We noticed the exclusions of African American women physicians from the WMJ and from the opportunities presented and documented in the WMJ. We therefore expanded our research beyond the WMJ to deliberately search for sources that document when, where, and how African American women physicians entered the medical profession and created their own professional networks. As Tessa Brown argues in her cultural rhetorics critique of white feminist discourse, there is an “ongoing and unresolved history of white supremacy in the United States women’s activism” (234). We seek to study this unresolved history by researching two overlapping, yet separate communities: those of white women physicians featured in the WMJ, and those of African American women who were largely excluded from the journal and community.

Our analysis is composed of two overlapping methods: first, we employed DH methods to create social network analyses of the community of women documented in the WMJ in the 1900, 1910, and 1919 volumes of the journal. From this distant reading analysis we make claims about how these white women used the journal as a means of social networking to support one another and challenge sexist institutions. We further support these claims with close reading of one smaller community that is documented in the WMJ in order to highlight the importance of attending to local contexts and analyzing the rhetorical strategies that women developed to support one another.

Because DH methods are a relatively new key tool for feminist historiography, we questioned how these tools may support feminist research practices. We asked, what can we learn about social and professional networks of women by employing DH methods? What do we learn about key actors, institutions, and centers of activity (and power)? What changes and movements can we trace over time? What can we learn when pairing DH methods with feminist rhetorical practices? What remains hidden, invisible, or excluded in the visualizations created via DH methods?

Second, we practice critical imagination to recover the African American women who were excluded from the WMJ. We conducted research beyond the WMJ to integrate African American women physicians into the social network analysis. We employ the feminist method described as critical imagination, a method that calls on scholars to search for and collect all available evidence in order to imagine, create, and visualize what might have been. In our case, this meant creating visualizations of the networks of African American women physicians based on extended research, and then superimposing those images onto the visualizations of white women’s networks. Creating an overlay of these two social networks is a practice of critical imagination that calls into relief the exclusions from the white community as well as the robust, supportive social network that African American women sustained.

Medical Education in Early 20th Century

Medical education in the US should be understood in the context of the Progressive Era (Luker). While this period was a time of dramatic and substantive social and political activism and reform, the changes made did not benefit all Americans equally. There was progress in matters such as government reform, women’s suffrage, scientific management, and academic professionalization. Simultaneously, however, racist laws and regulations were instituted that repressed and undermined opportunities for African Americans. The “separate but equal” racial segregation legalized in 1896 by the Supreme Court’s Plessy v Ferguson decision continued well into the 20th century, as did the Jim Crow laws, white terrorism that led to the Great Migration, and voter suppression.

Racism informed even one of the most crucial strides for women: birth control. Margaret Sanger’s revolutionary work in family planning, birth control options, and women’s reproductive freedom was paired with the espousing of eugenics and sterilization for population control of communities of color. Found throughout the WMJ during this time are racist medical practices and beliefs of eugenics, sterilization, and racist stereotyping.

At the time, white women physicians perceived their tireless efforts fighting sexism to be paying off. In 1900, the editors of the WMJ were buoyed by signs of progress. The number of women in medical school and women practicing medicine seemed to be increasing steadily: up to 5% of all physicians, estimated at approximately 7,000 women total (Morantz-Sanchez, “So Honored So Loved?” 232). However, by 1920 this celebratory climate had dissipated. As early as 1910, the number of women practicing medicine and attending medical school began to decline, and continued to decline for many decades. As medical historian Ellen More writes,

Between 1904 and 1915, many financially weak medical schools succumbed to external pressures to close their doors, while others—taking their cue from Abraham Flexner—drastically curtailed enrollments…Women graduates declined from 198 to 92, a decline of 54% … (“American Medical Women’s Association” 166)

The American Medical Association’s Committee on Medical Education had asked the Carnegie Foundation, led by educator Abraham Flexner, to conduct a survey of all American and Canadian medical schools. Published in 1910, the Flexner Report provided a comprehensive survey of medical educational practices and training standards, which at the time were widely variable. The report led to a dramatic tightening of the medical curriculum along with standardization of educational expectations and scientifically-based training requirements.

As a result, many women’s medical colleges began to close their doors. The new standards required more time, resources, and funding than were available to them. Within this context, the women’s rhetorical strategies in the WMJ evolved to address these additional challenges and foster solidarity among a shrinking number of women physicians within a context marked by increased struggle and marginalization (More, Fee, and Perry, “Introduction”).

In like manner, following the recommendations of the Flexner Report, 5 out of the 7 black medical schools in existence closed. In “Creating a Segregated Medical Profession: African American Physicians and Organized Medicine, 1846-1910,” (a report commissioned by the AMA Institute for Ethics to analyze “the roots of the racial divide within American medical organizations” and published in 2009 in the Journal of the National Medical Association), the authors report that the Flexner Report led to the creation of a medical system that was “separate, unequal, and destined to be insufficient to the needs of African Americans nationwide” (Baker et al. 501) during a time when 90% of the 9.8 million African Americans living in the US lived in the segregated south (501). Further, the authors of the report, Robert Baker, Harriet Washington, Ololade Olakanmi, Todd L. Savitt, Elizabeth A. Jacobs, Eddie Hoover, and Matthew Wynia, note,

In the United States, organized medicine emerged from a society deeply divided over slavery, but largely accepting of racial inequities. Throughout this period, racism was pervasive, and pseudoscientific theories of racial inferiority were common. Hospitals, training programs, and many medical and nonmedical organizations, in addition to the AMA, accepted or enforced racial segregation (510).

The AMA further institutionalized racist exclusion in the organization, the authors explain, by using parliamentary maneuvers to shift power to state medical associations in the selection of delegates, which obstructed African Americans from participation. The professional organization of women physicians would also exclude African American women from its founding in 1915 well into the 1940’s (More “American Women’s Medical Association” 169).

The Woman’s Medical Journal in Context

Published from 1893-1952, the Woman’s Medical Journal (later renamed the Medical Woman’s Journal), published research articles that report case studies, best practices, and research on medical findings and treatment. In addition, the WMJ published a range of editorial articles, reports on medical education and the status of women physicians, news items and social announcements, which were listed in sections titled “Items of Interest” and “Miscellany.” By printing editorial and miscellany content, women physicians used this venue to connect an internationally distributed community, announce professional opportunities, amplify their efforts, warn of inhospitable communities, and empower each other by outlining strategies for talking back to sexist institutions. Elsewhere, we closely analyze these announcements, noting that they include successes, collaborations, struggles, cautionary tales, and setbacks (Kirsch and Fancher). We conclude that the WMJ provides a fascinating portrait of the growing women’s medical community where “we find struggle on every page” (25-26). Along similar lines, both Susan Wells and Carolyn Skinner demonstrate, in their rich rhetorical studies of 19th century women physicians’ scientific writing and professional ethos, respectively, that these women had to negotiate the double bind of performing the feminine ethos of caregiving and a medical ethos, which required typically masculine performances that may not have been socially acceptable for women.

To use contemporary feminist language, the WMJ was conceived as being a venue for, by and with women physicians, not only “about” women. In the January 1899 volume, for example, Dr. Eliza Root1, the editor, reflects on the strides that medical women had made and articulates the hopes she has for the upcoming year and new century. She writes:

The Woman’s Medical Journal is yours for such an effort. Our mission is yours, and our columns, our strength, our influence is at your service. Let us make the year eighteen hundred and ninety-nine a memorable one to women in medicine. (10, emphasis added)

Here, Dr. Root calls upon readers to join forces and participate actively in shaping the future of the profession. Further, she urges her fellow women physicians to own the platform that the WMJ provides (“our mission is yours”), share their work (“our columns, our strength, our influence is at your service), show a united front (“with united, concentrated effort”) and advance the medical profession (a year of “great achievements”). In short, the editor appears conscious of her role as an advocate, educator, and sponsor of medical women as demonstrated in her frequent calls for action, participation, and involvement in the medical profession and in her explicit description of the WMJ as a collaborative forum for the advancement of women in medicine.

Yet once again, we note that the calls for community, collaboration, and solidarity did not include women of color. In 1915 the WMJ became the official organ of the newly founded Medical Women’s National Association (MWNA), which was a professional organization supporting women’s advancement in medicine. However, the MWNA denied membership to African American women. As More notes, “Shamefully, on the issue of racial equality in the profession, the MWNA did no more than keep pace with American health care institutions in general, most of which remained segregated until the 1960s… As late as 1939 the organization continued to reject applications for membership from otherwise eligible African American physicians” (“American Women’s Medical Association”169).

Employing Digital Humanities Methods: Affordances and Challenges

In rhetoric and composition, numerous research projects have utilized distant reading methods in order to visualize large-scale shifts in technology (Denson; Palmeri and McCorkle), rhetorical trends (Faris; Gatta; Gries), and social networks (Mueller “Grasping”; Mueller Network Sense). The power of DH methods, and distant reading in particular, lies in the ability to draw on large sets of textual data to reveal patterns, trends, and changes over time that are not visible with close reading and rhetorical analysis alone.

In an effort to better understand the history of medicine, a group of digital humanities scholars explored network analysis as “an object of study, a tool for analysis, a framework for collaboration, and a means of scholarly communication” (Viral Networks 4), not as a definitive representation of a problem or community. Used as a tool for interpretation, social network analysis offers ways for humanities scholars to “approach a problem in a different way, or understand what is missing in their sources or interpretations” (Viral Networks 5), identifying previously unseen connections and correlations. For instance, Jacqueline Jones Royster and Kirsch have reflected about the use of digital tools for studying the WMJ with the goal of “stepping back from the specificity of rhetorical analysis of artifacts and processes of communication to gather other layers of evidence in order to detect larger patterns of action” (“Social Circulation” 176).

We use digital humanities (DH) methods for distant reading because these methods can be strategic, innovative methods for studying women’s rhetoric. Jessica Enoch and Jean Bessette define distant reading as a technologically enhanced form of “not reading” that invites us into “a different way of encountering evidence” and foregrounds visual analysis and interpretation based on “pattern, repetition, and aggregation, a new type of resource” that prompts new types of questions (645).

At the same time, the use of DH methods has been taken up with care and caution by feminist scholars. Enoch and Bessette, for instance, caution us to recognize that distant reading may be counterproductive for the feminist goals of listening carefully and honoring the unique context and challenges of participants (621) and may reproduce some of the gaps and exclusions that are present in the archives (645-46). Like Enoch and Bessette, we hold reservations regarding distant reading and ask: Might distant reading reduce the complex lives of the women associated with the WMJ into simple data points on a graph? How might we attend to gaps or exclusions in the archives and reveal them in the visualizations? How might feminist rhetorical practices work with or against digital humanities methods? We offer our experience with DH for feminist research as an essay, an attempt that we enter into cautiously while recognizing its limitations.

Our methodology is further inspired by the work of Leah DiNatale Gutenson and Michelle Bachelor Robinson, who narrate their journey of searching digital archives for traces of two important African American 19th century educators, Susie Adams and Lottie Adams. As Gutenson and Robinson discovered more erasure than inclusion, they caution that even big data digital archives exclude African American women and conclude “that ‘open’ in digital spaces is not synonymous with inclusion, and in some ways it can actually be ‘closed’ to many underrepresented groups, particularly African American women” (73).

Gutenson and Robinson specifically address how digital archives are created and curated in ways that can perpetuate the exclusion and marginalization of African American women. They write,

In order to assure that the newly emerging field of the Digital Humanities and Historiography of Rhetoric and Composition attracts the work and perspectives of people of color, we must become race-cognizant multimodal scholars….We would argue that if we ignore the ways we utilize technology to construct the digital archives, these virtual spaces may continue to serve the majority culture and status quo rather than provide opportunities for revisionist inclusions. (87 emphasis ours)

Taking up Gutenson and Robinson’s critical approach to digital humanities research, we attempt to practice “race-cognizant multimodal scholarship” by revising and rethinking our distant reading methods to avoid perpetuating the exclusion of African American women physicians. Subsequently, we made the choice to read beyond the original scope of this project, the contents of the WMJ, in order to amplify the work and words of women of color, resounding within and against the discourse preserved in the WMJ. If we had used only the archival material from the WMJ, then our research would not have included any African American women. However, this is not a sign of silence on the part of the African American women physicians. Rather, the African American women were speaking loud and clear. They were largely excluded from the community of white women physicians and their published discourse.

We also recognize our responsibility as white women scholars not to perpetuate the racial exclusion of African American women in our research on women’s rhetoric. Instead, we seek to both recognize the rhetorical strategies that white women physicians employed to build solidarity in the face of severe sexism (Bonner; Morantz-Sanchez), and we seek to recognize the limits of their solidarity by calling attention to the exclusion of African American women physicians. Finally, we recover a portion of these African American women’s voices in order to listen to them speaking back to the community of white women physicians with whom they worked. It is not enough to simply note these silences, but instead, we highlight excluded African American women physicians by employing “critical imagination” (Royster and Kirsch, Feminist Rhetorical Practices) and create enhanced social network analyses that allow us to see two distinct, overlapping yet separate communities.

Analysis I:

Social Network Analysis: Visualizing White Women Physicians’ Networks in the WMJ

The first stage of analysis involved integrating both distant reading through social network analysis and close reading that situates the broader trends in particular women’s lives. As we designed our methodology, we were particularly inspired by Katherine Hayles who advocates for combining both distant and close reading to facilitate different ways of interpreting texts and discourses.

We want to emphasize that our methods began and ended with close reading. Coding hundreds of pages of the WMJ—whether a research article, an editorial, or a miscellany item— required us to gain a greater familiarity with the content because we recorded each and every item. We then used the visualizations to identify trends, patterns, and networks by viewing at a distance. These visualizations represented the discourse from a new point of view, which opened up new questions and lines of inquiry. From this new point of view, we returned to a close reading of the WMJ. This close reading allows us to view the community of women physicians in their embodied particularity and historical context.

We designed the social network analysis to visualize the relationships among people and institutions that are documented in the WMJ and that represent the relative connections among these actors2. We coded the WMJ for actors, defined as any person, group of people, or institution named in each article. Institutions most typically included medical schools and universities, hospitals, professional organizations, and state and regional medical societies, and community groups. The location of each actor on the network is determined by the number of connections: the more connections an actor has, the more centrally the actor is located in the graph.

We coded the 1900, 1910, and 1919 volumes because these years represent the community at the beginning of each decade3 and mark important milestones for the WMJ. In 1900, the editors celebrate their previous accomplishments and look with optimism to the new century. By 1910, the year of the Flexner Report publication, the WMJ evaluates women’s medical training, cautions women of the challenges that lay ahead, and encourages women to become active members of state and national medical associations. In 1919, the editors report on women’s efforts in World War I and the recovery work that followed, often internationally, and largely under the auspices of the American Women’s Hospital Association.

We also recognize the limitations of our coding choices: we selected only three years and were only able to include a selection of the people and institutions named in the WMJ. Subsequently, our visualizations do not include every person and institution mentioned in the journal. In addition, the editors WMJ did not include every woman physician or every important member of the community. Rather, they made choices regarding who and what to publish. Moreover, we made choices regarding the scope of our research, which affected who and what was included in the project. Hence, the visualizations do not represent the community as it was in reality or in completion. Rather, the visualizations represent a partial version of the community, as curated by the editors of the WMJ and as interpreted by ourselves as researchers.

Reading Social Networks in the WMJ

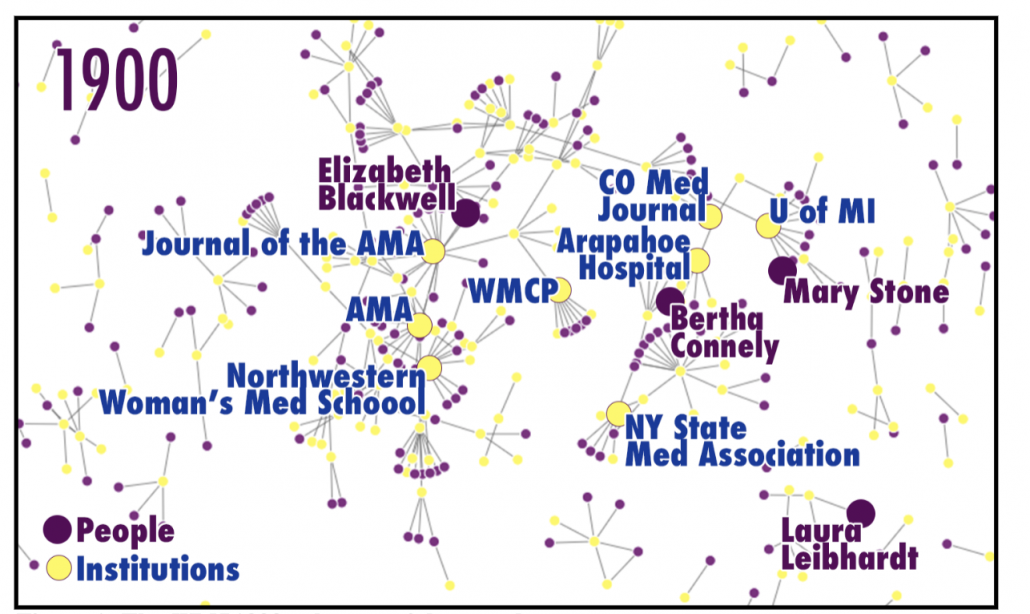

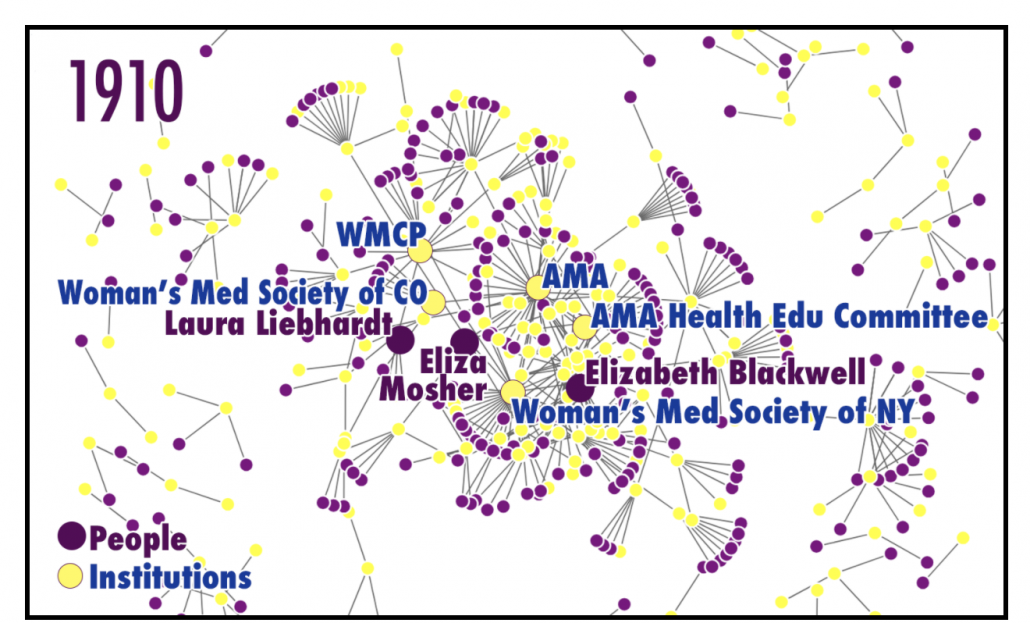

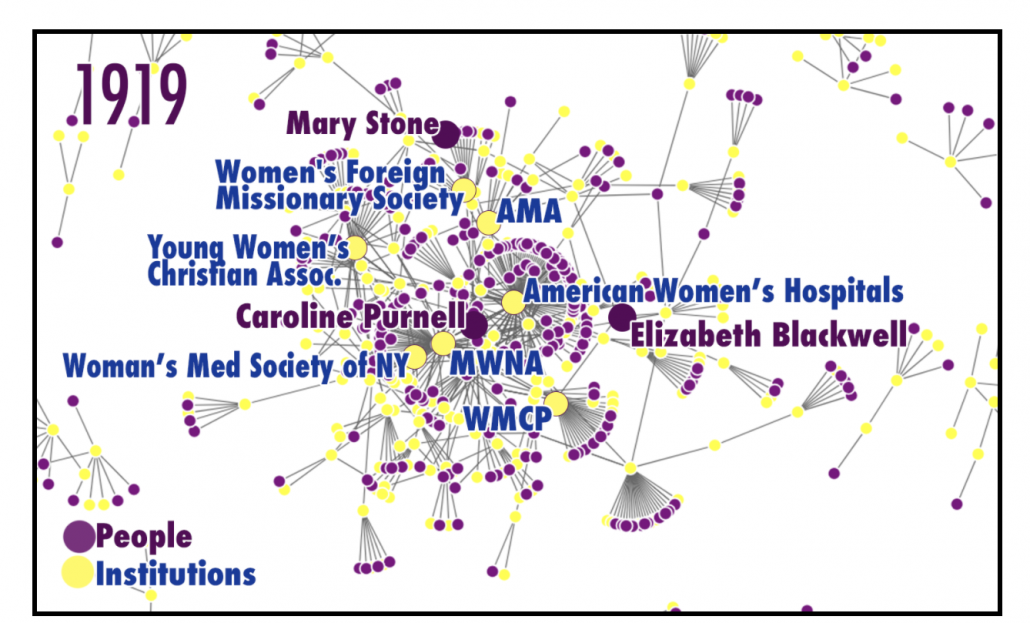

From the furthest distance, we see a discursive trend towards greater connectivity, centralization, and collaboration within professional organizations. Figs.1, 2, and 3 below illustrate this trend while also including labels that highlight select actors. To view the social networks without the obstruction of labels, see the appendix with Figs, 6, 7, and 8.

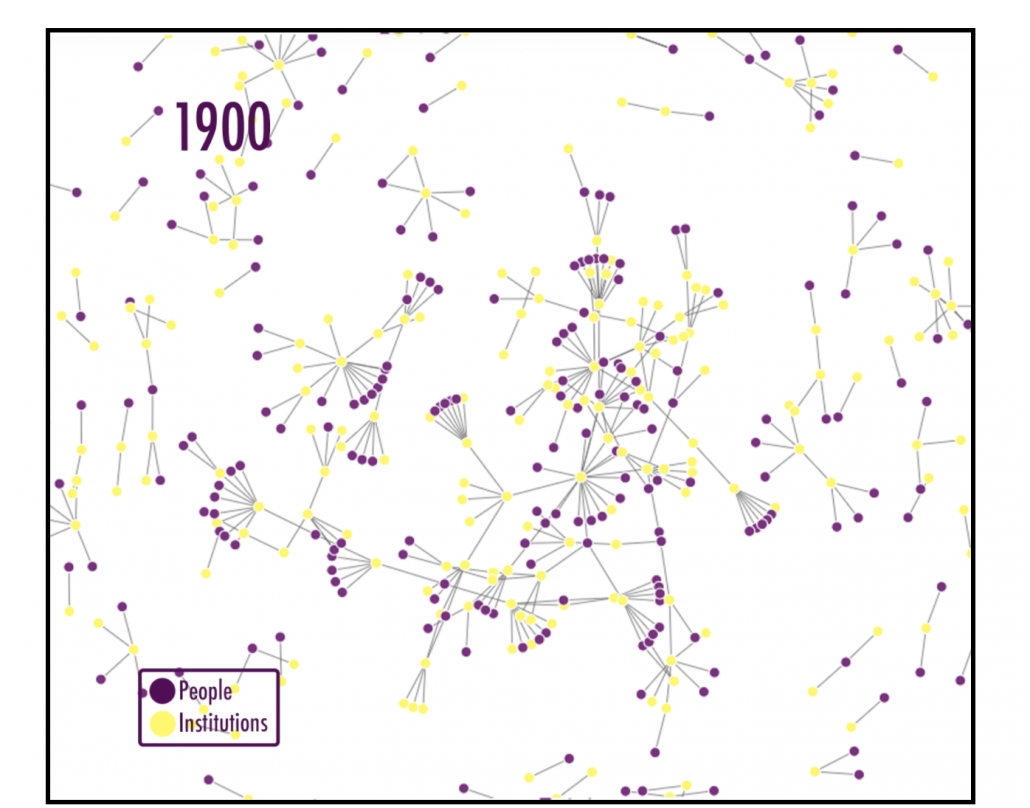

Fig. 1. The WMJ 1900 volume social network

In Fig. 1 (above), we visualize a network of people and institutions included in the 1900 issue (see Fig. 6 in the appendix for image without the labels). This social network is relatively dispersed, with numerous smaller clusters distributed across the image. Dr. Elizabeth Backwell, the first American woman to earn a medical degree, is centralized and connected to many people and institutions, indicating her continued leadership among women physicians.

The institutions that are central and include the most connections are primarily women’s medical colleges, especially Northwestern and the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP). Often, the editors of the journal would highlight a woman’s professional credentials by listing membership and leadership roles in professional communities. The New York State Medical Association hosted professional events, which many women physicians attended.

The institution with the most connections is the American Medical Association, which women physicians were actively trying to join and participate in. At the time, the AMA appears to be the most significant professional organization for women physicians. Women were technically allowed to become members of the AMA; however, they first had to be selected and approved by their state medical society (Baker et al. 507).

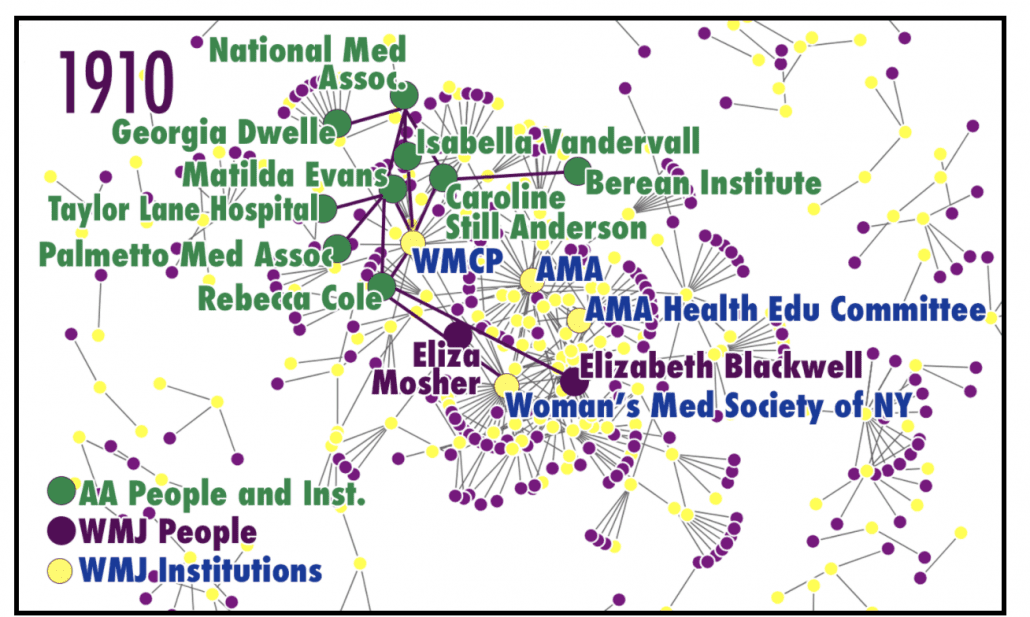

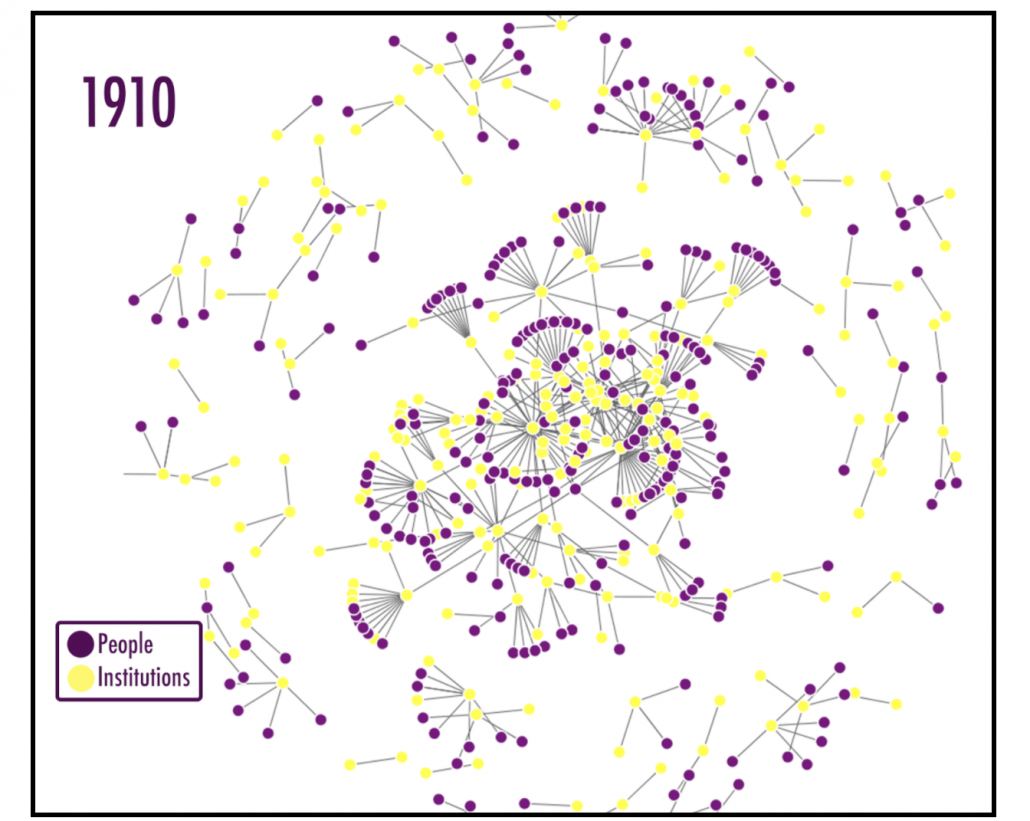

Fig. 2. The WMJ 1910 volume social network.

Fig. 2 (above) illustrates the social network of people and institutions included in the 1910 issue (see Fig. 7 in the appendix for image without the labels). The first change in the network shows that, by 1910, the social network appears more densely connected. There are more people and institutions tightly bound in the center of the image. Like the 1900 social network, the AMA is the central professional organization, which indicates its continued relevance for white women physicians. In addition, the AMA Health Education Committee, which produced the Flexner Report, is also central. We note another change in network: women’s organizations appear more centralized and are connected to more people, especially the Women’s Medical Societies of New York and Colorado.

As in 1900, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell is a central figure. She died in 1910, and the journal dedicated many pages to documenting and celebrating her long career and many contributions to women in medical professions. Dr. Eliza Mosher also appears in the center of the network, connected to many people and institutions. Dr. Mosher was the long-time editor of the WMJ and worked tirelessly to advocate for women in medical professions.

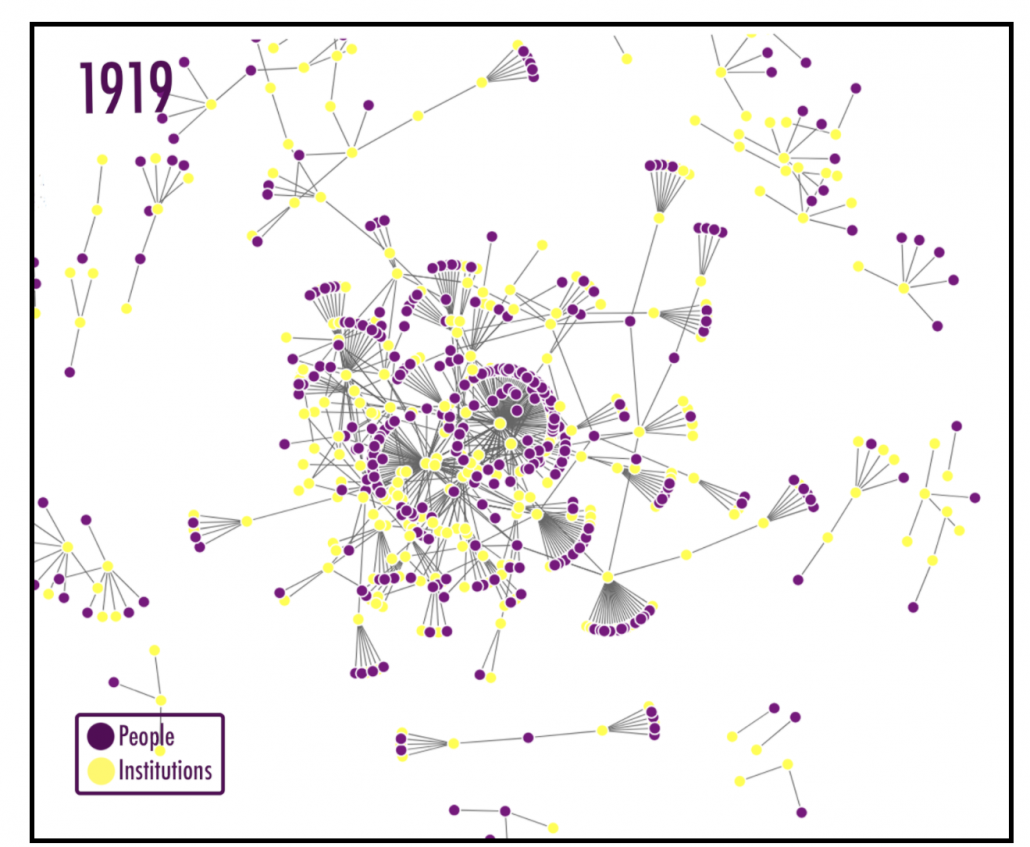

Fig. 3. The WMJ 1919 volume social network.

Fig. 3 (above) visualizes the social network of people and institutions included in the 1919 issue (see Fig. 8 for image without the labels). The most significant change in the network is that, again in 1919, the network appears even more dense with people and institutions. There is a tight, dense cluster in the center with relatively few marginal or unconnected clusters of actors.

We also note significant changes regarding what institutions are central. In 1900 and 1910, national, male-dominated professional organizations, especially the American Medical Association (AMA) and subcommittees of the AMA, are at the center. In 1919, women-led professional organizations, especially the National Medical Women’s Association (NMWA) and the American Women’s Hospitals (AWH), are at the center and include dense connections. We also find it important to note that Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, though not as central and connected, still appears toward the center of this visualization. Even 9 years after her death, the editors of the WMJ continue to invoke her name, reputation, and legacy as a mentor and trailblazer for women in medical professions.

Interpreting Social Networks in Context

It is important to interpret the trends that we see as indicative of a rhetorical discursive phenomenon. In other words, the community appears more centralized and connected in the 1919 visualization (Fig. 3) than it does in the 1900 visualization (Fig. 1). This may or may not mean that the actual community of women physicians was experiencing greater connectivity and collaboration. Rather, this visualization indicates that their rhetorical practices began to emphasize great connectivity, solidarity, and collaboration.

When we put this trend towards greater connectivity in historic context, the choice to highlight women’s organizations in 1910 (Fig. 2) and then even more so in 1919 (Fig. 3) can be interpreted as a rhetorical response to continued struggles and sustained setbacks. The numbers of women physicians practicing began dropping after 1910 and continued to decline for decades. More notes that, “From a steady rise to 6% of all physicians in 1910, the number of women practitioners dropped back to the 5% level by 1920. Never were women in medicine more in need of a powerful, united voice” (“American Women’s Medical Association” 166). In response to this decline, the WMJ placed a strong emphasis on solidarity and collective support for women in medicine.

The primary rhetorical discursive trend that this social network analysis makes visible is the important rhetorical strategy of naming. The editors include long reports naming every woman who participated in an event or contributed towards public health initiatives. They publish directories of all white women physicians practicing in a specific area, city, or hospital. Whenever they named a woman physician, they would also list her professional credentials, including degrees, places of employment, internships, and professional memberships.

The importance of these naming practices can be identified in the figures above. For instance, in Fig. 3 from 1919 the American Women’s Hospitals is central and is connected to a thick network of people. In monthly reports during 1919, the WMJ would list every woman who contributed to the vast, international humanitarian work undertaken after the end of WWI through the American Women’s Hospitals.

The naming practice is an important feminist rhetorical choice. These women likely struggled for recognition in the male dominated journals, hospitals, and local communities. The editors’ use of naming practices—identifying, listing, and acknowledging individual women physicians—serves as a record of accomplishments and praises women for their tireless and fearless work. It also establishes women’s credibility, expertise, and professional ethos (Skinner) and brings visibility to their successes and struggles.

In addition to making visible the work of women physicians, this naming practice served another rhetorical purpose: the WMJ facilitated collaboration. Readers of the WMJ could learn about the work of other women physicians and connect to these physicians and associations for support, questions, and collaboration. The connections that we see in the WMJ were not exclusively on the page. The women were gathering for meetings, to collaborate on public health projects, and to discuss medical as well as social issues. The editors included many invitations to meetings, conferences, and even invitations to tea. By choosing rhetorical practices such as naming and inviting, the editors of the WMJ made visible the labor of the women physicians and facilitated further collaboration.

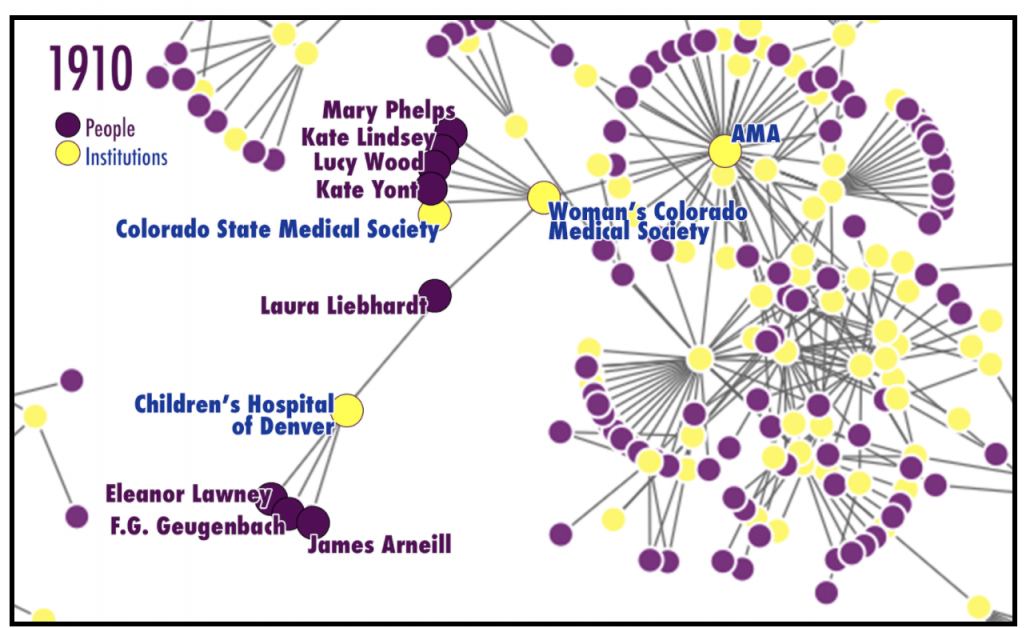

In order to illustrate the importance of this rhetorical practice of naming, we examine one community of white women physicians based in Colorado. Their network is visible in all three of the years as a cluster that attached to the center through their connection to the American Medical Association and the Medical Women’s National Association. While connected to the center, this community is also located to the side of the primary central cluster, suggesting that the community is tangentially connected to the community based in New York City. In particular, it appears that Dr. Laura Liebhardt was a leader and mentor in this community, appearing in 1900, 1910 and again in 1919 (included in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, and Fig. 3).

Fig. 4. Close-up view of Colorado-based women physicians from the “Denver Letter” in the WMJ February 1910.

Fig. 4 (above) highlights this Colorado-based community and their rhetorical practice of naming. We can see the extensive—and powerful—rhetorical practice of identifying individual women physicians and their credentials. For instance, the 1910 February issue contains the annual meeting report of the Women’s Colorado State Medical Society, titled “Denver Letter” (35-36). First, the report names elected officers of the Women’s Colorado State Medical Society, including Drs. Liebhardt, Mary Phelps, Kate Lindsey, Lucy Wood, and Kate Yont, along with their institutional affiliations and locations (35). This network of officers is visualized in figure 4. Second, the Denver Letter includes the verbatim address delivered by Dr. Liebhardt, who, like the WMJ editor, employs the practice of identifying women physicians by name, in this case, the women working on the AMA educational committee.

Through these extensive naming practices we can trace a rich set of primary and secondary connections—the local Colorado network and the national AMA network of women physicians, with a total of fifteen women identified in the Denver Letter. Moreover, the report includes observations about the social nature of the event, stating that “the ladies then adjourned to the banquet table, where matters previously suggested were more fully discussed and where a delightful social hour was enjoyed” (35). This report represents a rich example of the continued, extensive naming practices employed by the WMJ editors and members of women’s medical societies, allowing us to trace several clusters of women physicians, both at the local and national levels.

Who Is Missing? Not Naming as a Means of Exclusion

While we note the powerful practice of naming, these distant reading methods also made visible the scale of exclusion. The visualization we created do not include any African American women. The editors of the WMJ did not name any African American women at all during the years 1900, 1910, and 1919. Thus, while they deploy a rhetorical practice of naming to support white women, they also deploy a racist rhetorical practice of not naming as a means of exclusion.

While this community supported and advocated for white women, we again ask: who may be missing from this network? And again we find the answer that African American women have been excluded. For instance, in 1901, Dr. Justina Laurena Ford became the first African American woman to be licensed to practice medicine in Colorado. Dr. Ford moved to Denver and began practicing at the same time as Dr. Laura Liebhardt, discussed above. Dr. Liebhardt’s name appears in every single social network. However, Dr. Ford’s name was not included in any visualization. She was not invited to tea nor was she included in “Denver Report” in the WMJ.

Dr. Ford practiced medicine for 50 years, becoming well-known in the city for delivering over 8,000 babies and caring for African American and immigrant patients who often would not be treated by white doctors. Dr. Ford applied for entry and was consistently denied into the Colorado Medical Society, the Denver Medical Society, the Women’s Colorado State Medical Society, and the American Medical Association. This racist exclusion had real effects on Dr. Ford’s career. Only doctors who were members of the Denver or Colorado Medical Societies were permitted to practice in the Denver Hospital. Because the medical societies did not admit African American doctors, the hospitals then would also not allow Dr. Ford to practice there. Dr. Ford was persistent. She applied and reapplied for membership to the medical societies. In 1949, she petitioned again writing, “many patients wonder why I do not go to hospitals. I see it establishes an inferiority complex in their minds. It has required patience and fortitude to endure as I have, from 1902 to 1949” (letter published Riley, 37-39). After nearly 50 years practicing medicine in Denver, she was admitted to Denver Medical Society in 1950, just two years before her death.

In the next section, we will continue to address the extent of racist exclusion and also practice critical imagination so that we do not reinforce this racist exclusion in our archival research.

Analysis II:

Critical Imagination: Recovering African American Women Physicians’ Legacy

Thus far, we have interpreted what we see in the social network visualizations. As feminist scholars of rhetoric, we must also ask: Whose voices are missing? What are the gaps, blind spots, and omissions? As Gutenson and Robinson found, digital archival research may be open to all, but that does not mean inclusive of all, especially for African American women.

Royster’s and Kirsch’s discussion of archival research methods offer us the analytic concept they call “critical imagination,” which asks us to gather all the available evidence and then imagine what might have been, filling in the gaps, silences, and omissions as we learn more about the historical contexts and times. We draw on the definition of critical imagination as first introduced by Royster in Traces of a Stream, which prioritizes “a commitment to making connections and seeing possibility… and functions as a critical skill in questioning a viewpoint, an experience, an event, and so on, and in remaking interpretive frameworks based on that questioning” (83). Following this definition, we first question the viewpoint offered through the distant reading by asking “who is included” and “solidarity for whom”? From there, we continue to practice critical imagination by “remaking interpretive frameworks.” In this case, we sought to enhance our own interpretive framework, created in the first social network analysis, by “making connections and seeing possibility.” In particular, we use critical imagination to remake the critical framework so as to render visible African American women’s presence and contributions to the medical professions.

First, we compiled a list of African American women physicians practicing between 1900-1919. We identified 37 in total4. Then, we used the digital search tool in the Hathi Trust to search for these women’s names in the digital archive of the WMJ. In our original research, we included only the 1900, 1910, and 1919 volumes. In those volumes, the editors of the WMJ did not name, publish, or cite any of the 37 African American women physicians. In order to further pursue the presence or exclusion of African American women from the WMJ, we expanded the scope of our research. We searched every volume from 1900 through 1919 for each of these African American physician’s names.

In the 240 WMJ issues published between 1900-1919, six African American women are named:

- three announcements of professional achievements (Dr. Nellie Benson 1903, page 95; Dr. Georgia R. Dwelle 1904, pg. 182; Dr. Matilda Evans 1911, pg. 107 and 1915, pg. 42),

- two death announcements (Dr. Sarah G. Jones 1905 pg. 162; Dr. Susan Maria Smith McKinney Steward 1918, pg. 90), and

- one article by an African American woman (Dr. Isabella Vandervall 1917, pp. 156-58).

The WMJ was in the practice of publishing an annual directory with names and addresses of women physicians practicing medicine in each state. None of the 37 African American women who we identified are included in these directories.

Critical Imagination: Reading the Gaps

Figs. 1 through 4 were generated computationally, using an algorithm to generate the network. Below, Fig. 5 is based on secondary research and was created using critical imagination. Starting with the list of 37 African American women physicians, we identified how the African American women physicians were connected to each other and to the medical institutions. From that research, we imagined how a social network analysis might represent this community, and overlaid these African American women and the institutions that they were a part of onto the network from the 1910 issue of the WMJ5. From this imagined social network, we highlight how the African American women were often connected to the same schools as the white women’s community, excluded from the white professional communities, and how the women supported organizations by and for African American communities.

Fig. 5. African American women physicians overlay on 1910 network.

The visualization above, Fig. 5, illustrates our critical imagining of a social network that African American women created to support each other and provide care to African American communities. Dr. Rebecca Cole was placed closest to the center of the network because she was the first African American woman to earn a medical degree. She is connected to both Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell and Dr. Eliza Mosher because she worked with both of these leaders among white women physicians. The Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP) is a centralized institution for African American women as well because several African American women earned their medical degrees from this college, including Dr. Rebecca Cole, Dr. Caroline Still Anderson, Dr. Isabella Vandervall, and Dr. Matilda Evans.

While African American women physicians were excluded from many of the professional organizations and also from the WMJ, they supported each other and supported African American communities by creating and leading organizations including the National Medical Association and its journal6. We have tried to make this visible on the social network above. The National Medical Association, the professional organization by and for African American physicians, is connected to four women—Georgia Dwell, Isabella Vandervall, Caroline Still Anderson, and Matilda Evans—because all of these women were members, and both Dr. Dwell and Dr. Evans served as Vice-Presidents. In addition, these women created new organizations to support African American communities, which we highlight by drawing connections between these women and the professional organizations that they helped to found.

Next, we highlight the work of three of these women—Dr. Dwell, Dr. Evans, and Dr. Vandervall—in order to feature how each build professional networks and to highlight their struggles against racist exclusion from white women’s professional communities. We focus on Drs. Dwell, Evans, and Vandervalls’s stories because they are three of the six African American women mentioned in the WMJ, and because they were accomplished physicians and distinguished leaders in their communities.

In 1904, the WMJ included an announcement detailing that

Dr. Georgia R. Dwelle graduated in medicine recently from the Meharry Medical College, Walden University, Nashville, Tenn. She took the examination of the State Medical Board of Georgia. She gained an average of 97 and stood second in a class of about fifty. She will practice medicine at her home, Augusta, Georgia” (182).

Dr. Dwelle (1884-1977) later established the first “mother’s club” to care for and support African American mothers. She established the first African American-serving clinic for venereal disease, which was located in Athens, Georgia. Dr. Dwelle held leadership positions in professional and social clubs for African American communities. Notably, she served as Vice-President for the National Medical Association (Changing the Face of Medicine, Georgia R. Dwelle).

In 1911, the WMJ announced that Dr. Matilda A. Evans (1872-1935) was a physician in charge of the Taylor Lane Hospital in Columbia, South Carolina (107), the hospital she founded in 1901. In February 1915, the WMJ included a second announcement (pg. 42) about the second hospital Dr. Evans founded, St. Luke’s Hospital (“Historic Columbia”). This was the only hospital to care for the African American residents of Columbia, a city with over 10,000 African American residents. Dr. Evans, born in Aiken, South Carolina, grew up amidst the turmoil of reconstruction and the threat of violence from white supremacists. Upon graduating from the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, she returned home, becoming the first African American woman to be licensed to practice medicine in South Carolina (Hine).

Dr. Evans built her reputation as a top-rate medical professional and committed herself to advocating for the economic and medical needs of African American communities. As medical historian Darlene Clark Hine explains, “concepts of soul, caring, racial uplift, and alleviation of suffering shaped Evans’s evangelical understanding of her medical missionary stewardship and sense of calling in Jim Crow South Carolina” (17).

Dr. Evans was denied membership and leadership opportunities in many predominantly white medical communities and professional organizations. Nevertheless, she served as the president of a state medical association, the Palmetto Medical Association. She founded the Negro Health Association of South Carolina, a nurse training program with a focus on public health initiatives, and she edited its official journal, The Negro Health Journal of South Carolina.

The commitment of Dr. Evans and Dr. Dwell to organizations for African American medical professionals also enacts the community-centered rhetoric practices that Jacqueline Jones Royster identified in the 19th century club movement among African American women:

From the shared space of club work these women articulated a ‘common good,’ charted courses of action, raised voices in counter distinction to mainstream disregard, and generated at least the capacity—if not the immediate possibility…to make themselves heard and appropriately responded to. By this process, the club women sustained their roles as critical sources of support for the educational, cultural, social, political, and economic development of the African-American community. (217)

Dr. Evans and Dr. Dwell both worked tirelessly within African American communities in South Carolina and Georgia to promote health and medical care, as well as support the next generation of women in medicine, especially the professional development needs of African American nurses, women, and children. Both women worked as actively in the medical professional as they did in education and activism, thereby serving as historical models for what Tamika Carey describes as “rhetorical healing,” the importance of education and knowledge that allows African American women to focus on self-help and wellness campaigns during the last twenty-five years.

In Fig. 4 above, we have highlighted their connections to the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and the National Medical Association as well as several medical organizations led by and for African Americans. We could only include a few of these professional organizations on the visualization above. Therefore, we emphasize that these women were active leaders in many more medical communities, as well as in literary, social, educational, and religious communities, as rhetorical scholars Shirley Wilson Logan, Beverly Moss, and many others document so richly.

In the only WMJ article authored by an African American woman, entitled “The Problems of Women of Color” from 1917, Dr. Isabella Vandervall (later Vandervall Granger) describes her experience of both racism and sexism as she pursued an internship in a hospital. She argues that the new requirement of an internship was a major roadblock to African American women. She describes her experience applying to three different internships, all of which rejected her explicitly on racist grounds. One hospital sent her an acceptance letter, but when Dr. Vandervall arrived, they immediately rescinded the offer, saying, “You can’t come here; we can’t have you here! You are colored! You will have to go back!” (158).

Dr. Vandervall, who was at the top of her graduating class, turned to her trusted mentor, a white woman who taught at the New York Woman’s Medical College. In an attempt to reassure Dr. Vandervall, the woman explained that “she had never thought of me [Vandervall] as colored; she simply thought of me as one of the girls…but now that I was applying for a position as intern the situation was different” (157). This teacher’s reaction is significant because we can see the point at which solidarity was denied. The teacher accepted African American women as students and even professed to be “color blind.” However, she would not accept her own African American student to work alongside her as a colleague and practicing medical professional.

Dr. Vandervall writes with conviction, care, and commitment to her work as a physician, especially for other women of color who are so often denied medical care. She ends by directly addressing progressive white Americans:

It casts a serious reflection upon those white people—democratic and philanthropic Americans—who lavishly endow colleges and hospitals and allow colored girls to enter and finish their college course, and yet, when one steps forward to keep pace with her white sisters and to qualify before the State in order that she might do the same service for her colored sisters that a white woman does for her, those patriotic Americans figuratively wave the stars and stripes in her face and literally say to her “what do you want, you woman of the dark skin? Halt! You cannot advance any further.” I ask, is this fair? (158)

The entire letter is a critique of a racist system with a focus on Dr. Vandervall’s particular experience. In the conclusion, Dr. Vandervall broadens her critique beyond her own experience in an indictment of white people broadly and white women in particular. This conclusion is especially potent. Here, Dr. Vandervall’s speech act can be placed in the long rhetorical tradition of Black Women “talking back” which bell hooks describes as,

Moving from silence into speech is for the oppressed, the colonized, the exploited, and those who stand and struggle side by side, a gesture of defiance that heals, that makes new life and new growth possible. It is that act of speech, of “talking back,” that is no mere gesture of empty words, that is the expression of our movement from object to subject—the liberated voice. (9)

Because Dr. Vandervall is demonstrating her qualifications as a top medical student as well as her rhetorical skill, this letter also fits in the rhetorical tradition that Gwendolyn Pough identifies later in hip-hop as “bringing wreck,” which Pough defines as Black Women’s rhetorical performance of both resistance as well as excellence. In her conclusion, Dr. Vandervall identifies the limits of solidarity: white women may say good words and have good intentions to “give aid” to African American communities, but only as long as they remain a step behind white women. Dr. Vandervall finds that the gesture towards solidarity is revoked when African American women strive to work side-by-side with white women.

By publishing Dr. Vandervall’s critique of racist white women, the WMJ editors make at least one gesture to acknowledge racist exclusion. However, Dr. Vandervall’s experience is dismissed in the next issue. The WMJ published a response in which Dr. Emma Wheat Gillmore offers statements of empathy, while, at the same time, suggesting that the prohibition against African American women may be warranted. Dr. Gillmore both dismisses Dr. Vandervall’s experience of racism and suggests that Dr. Vandervall may lack qualifications. As medical historian More explains, Dr. Vandervall was not alone in these struggles: “few [African American women] could obtain internships; even fewer could secure one at an integrated hospital” (110). Disturbingly, many internships were denied to African American physicians well into the 1940’s.

This exclusion is just one historical example of what Kimberlé Crenshaw has identified as intersection oppression, which describes African American women’s experiences under both racist and sexist systems of oppression. African American women have been and continue to be excluded and marginalized on the basis of both race and gender. In the case of the community of women physicians identified in the WMJ, this oppression means that while white women extended solidarity and support for one another to improve the status of white women, African American women physicians were excluded, as we can see detailed in Dr. Vandervall’s article.

Our research on African American women physicians is just beginning, and we hope to have opened more questions and lines for future research. For instance, more work could be done to study the professional organizations and mentoring networks that these women engaged in to sustain themselves and support other African American physicians. Our research began with the WMJ and the white women’s community. We could ask, how might the social network analysis appear differently and lead to different conclusions if we center on the discourse and community documented in the Journal of the National Medical Association, the professional organization for African American physicians which continues to publish to this day? We have highlighted just three African American women’s lives and careers. But there were many others; more research could study their writing and social networks in order to examine how their medical practice was committed to racial uplift and empowerment of African American communities. In this article, we have focused on the relationship between white and African American women physicians, but further research could explore the complex role of international women physicians who do appear relatively regularly in the pages of the WMJ.

Conclusion

We initiated this project recognizing that early women physicians, struggling against severe sexism in the medical profession, built communities of solidarity that have been preserved on the pages of the Woman’s Medical Journal. As we continued to read and engage with their work, we also saw more clearly the complexity, limitations, and exclusionary practices of these white women and the community they supported. As we conclude this article, we also seek to make visible the limitations and racist practices they enacted, all the while professing solidarity among women physicians. The white women’s discourse both articulated a strong need for solidarity and gender equality, and at the same time their practices refused solidarity with African American women and perpetuated racial injustice. This is a contradiction that continues to plague contemporary feminist communities.

For our analysis, we employed two main methods: First we employed DH methods to create social network analyses of women’s professional networks over time and combined these analyses with close reading to allow for describing specific women in historical contexts. When we primarily close read, we clearly hear women’s calls for solidarity and mutual support, amplified in a resounding way from the pages of the WMJ. However, when we step back and read from a distance, we notice not only changes across networks, social conditions and influential actors, but we can also discover silences, erasures, and missing voices. With distant reading alone, we can call attention to the exclusion of African American women physicians. Two, we employed critical imagination to go beyond simply noticing absent voices and racist practices of exclusion. Instead, we decided to search for contributions of African American women physicians, foreground their writing, and locate their work in relation to the community of white women in the WMJ. Importantly, we hope to begin documenting African American women physicians’ leadership and legacy within the African American community and beyond, thereby suggesting avenues for further research.

This research is especially important now given that white feminist communities continue to fail in efforts to build solidarity with African American women and work for racial justice. As we move forward, we continue to ask about our own feminist communities: Solidarity for whom? On whose terms? Whose voices are included? And whose voices are excluded?

Endnotes

- We have added the title “Dr.” for women with M.D. degrees throughout this article because the journal editors themselves used this title consistently in their effort to establish and reinforce women’s professional ethos, credentials, and achievements. Hence, we find it imperative to honor this practice as we tell these women physicians’ stories and accomplishments more than a century later.

- In coding, we included up to 5 people and up to 5 institutions per article, announcement or report. For the vast majority of the articles and announcements, we included every person and institution named. However, if articles or announcements included long lists of names and institutions, then we only included the first 5 people and 5 institutions. We believe that our sample size includes the majority of the actors and is large enough to represent the general trends of the community. To make the actual visualizations, we collaborated with University of California Santa Barbara data science student, Raul Eulogia, who created the social network analysis by processing the data in R and then added interactive features using JavaScript.

- We included all original content of the WMJ as we coded the years 1900, 1910, and 1919 while noting two caveats. First, two months of the 1919 volume were not available through the Hathi Digital Trust, the digital archive we used for our coding and analysis. Two, we only coded from January through September of 1900 because this volume was over twice as long as every other volume. Subsequently, we coded an equal number of pages from each volume. If we had included every page of the 1900 volume, then the network analysis would be weighted towards 1900. In total, this included 30 issues, 1017 pages, and 745 separate articles or announcements.

- For lists of African American women physicians see Bettina Aptheker’s list of African American women graduates of medical school (100) and the Black Women Physician Project hosted at the Legacy Center archives and special collections at Drexel University. We cannot be sure of the completeness of our list of 37 women, given that the historical records are partial, and that the various numbers that we found from secondary sources vacillate between 20 to 100 African American women physicians in the late 19th and early 20th century (see Aptheker 92; Ward 53). Our list includes women physicians practicing or in medical school between 1900-1920 who were included in the Black Women Physicians Project. We also verified these names in secondary sources and double-checked for additional names in research by More, Morantz-Sanchez, and Wells.

- We created this overlay for the 1910 network because it allows for the best visual representation: it includes black women’s professional organizations in relation to several regional white women’s professional organizations. The networks are more spread out because the national women’s organizations were not as centralized as in 1919. Hence, we were able to create a visualization that allows us to superimpose two networks without losing readability.

- For a discussion of the Journal of the National Medical Association, published by and for African American physicians, see Savitt.

Acknowledgements

Our research depended on collaboration, mentoring and support from our own broad community. First, this research benefited greatly from the expertise and care of the Kairos Camp faculty, especially Cheryl Ball, Douglas Eyman, Kristin L Arola, Karl Stolley, David Rieder, Madeleine Sorapure, Jeff Kuure and the funding provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Additionally, Patricia Fancher would like to thank the CCCC for supporting this research with an Emerging Research Grant, which offered the gift of time and technical support. The Writing Program at the University of California Santa Barbara supported undergraduate research assistants, Ari Gilmore and Pranati Shah. We thank Raul Eulogio, data science student at UCSB, for his expertise, time, and patience as we collaborated to create the social network analyses. Gesa Kirsch would like to acknowledge the support of a National Humanities Summer Stipend that offered her opportunity to dive deeply in the Woman’s Medical Journal. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Gesa Kirsch also would like to thank Bentley University for providing research and travel support for this collaboration. Alison Williams appreciates the research and travel support from Chapman University’s Wilkinson College, and the scholarly support particularly from Ian Barnard, Doug Dechow, and Jana Remy.

Works Cited

- Aptheker, Bettina. Woman’s Legacy: Essays on Race, Sex, and Class in American History. U of Massachusetts P, 1982.

- Baker, Robert B., Harriet A. Washington, Ololade Olakanmi, Todd Savitt, Elizabeth A. Jacobs, Eddie Hoover and Matthew K. Wynia. “Creating a Segregated Medical Profession: African American Physicians and Organized Medicine, 1846-1910.” Journal of the National Medical Association 101.6 (June 2009): 501-512.

- Bonner, Thomas Neville. To the Ends of the Earth: Women’s Search for Education in Medicine. Harvard UP, 1992.

- Brown, Tessa. “Constellating White Women’s Cultural Rhetorics: The Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching and Its Contemporary Scholars.” Peitho 20.2 (2018): 233-260.

- Carey, Tamika L. Rhetorical Healing: The Reeducation of Contemporary Black Womanhood. SUNY Press, 2016.

- Changing the Face of Medicine. “Biography of Georgia Rooks Dwelle.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2015.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stan. L. Rev. 43 (1990): 1241.

- Denson, Shane. “Visualizing Digital Seriality or: All Your Mods Are Belong to Us!.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 22.1 (2017).

- “Denver Letter.” Woman’s Medical Journal 20.2 (February 1910): 35-36.

- Enoch, Jessica, and Jean Bessette. “Meaningful Engagements: Feminist Historiography and the Digital Humanities.” College Composition and Communication 64.4 (2013): 634-660.

- Ewing, E. Thomas, and Katherine Randall. Viral Networks: Connecting Digital Humanities and Medical History. Virginia Tech Publishing, 2018.

- Faris, Michael. “Assaying Queer Rhetoric: Distant Reading the Rhetorical Landscape for Queers and Feminists of Color.” Peitho 20.2 (2018): 160-97.

- Gaillet, Lynee Lewis, and Helen Gaillet Bailey, eds. Remembering Women Differently: Refiguring Rhetorical Work. Lynee Lewis Gaillet and Helen Gaillet Bailey, eds. Columbia: U of South Carolina P, 2019.

- Gatta, Oriana. “Connecting Logics: Data Mining and Keyword Visualization as Archival Method/ology.” Peitho (2014): 89-103.

- Gilmore, Emma Wheat. “A Call To Arms.” Women’s Medical Journal 27.8 (August 1917): 183-184.

- Gries, Laurie. “Mapping Obama Hope: A Data Visualization Project for Visual Rhetorics.” Kairos 21.2 (2017).

- Gries, Laurie E. and Collin Gifford Brooke, eds. Rhetoric, Writing, and Circulation. Utah State UP, 2018.

- Gutenson, Leah DiNatale and Michelle Bachelor Robinson. “Race, Women, Methods, and Access: A Journey through Cyberspace and Back.” Peitho (2016): 71-92.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. “How We Read: Close, Hyper, Machine.” ADE Bulletin 150.18 (2010): 62-79.

- —. “Combining Close and Distant Reading: Jonathan Safran Foer’s Tree of Codes and the Aesthetic of Bookishness.” PMLA 128.1 (2013): 226–231.

- Hine, Darlene Clark. “The Corporeal and Ocular Veil: Dr. Matilda A. Evans (1872-1935) and the Complexity of Southern History.” The Journal of Southern History 70.1 (2004): 3-34.

- Historic Columbia. 2027 Taylor Street. Dr. Mathilda Evans House.

- hooks, bell. Talking Back: Thinking feminist: Thinking black. South End P. 1989.

- Kirsch, Gesa E., and Patricia Fancher. “Social Networks as a Powerful Force for Change: Women in the History of Medicine and Computing.” Remembering Women Differently: Refiguring Rhetorical Work. Lynee Lewis Gaillet and Helen Gaillet Bailey, eds. Columbia: U of South Carolina P, 2019. 21-38.

- Logan, Shirley Wilson. With Pen and Voice: A Critical Anthology of Nineteenth-Century African American Women. Southern Illinois UP, 1995.

- —. Liberating Language: Sites of Rhetorical Education in Nineteenth-Century Black America. Southern Illinois UP, 2008.

- Luker, Kristin. “Sex, Social Hygiene, and the State: The Double-Edged Sword of Social Reform.” Theory and Society 27.5 (1998): 601-634.

- Morantz-Sanchez, Regina Markell. Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American Medicine. U of North Carolina P, 2005.

- —. “So Honored; So Loved?: The Women’s Medical Movement in Decline.” Send Us a Lady Physician: Women Doctors in America, 1835-1920. Ed. Ruth Abram. Norton, 1985. 231-246.

- More, Ellen S. Restoring the Balance: Women Physicians and the Profession of Medicine, 1850-1995. Harvard UP, 1999.

- —. “The American Medical Women’s Association and the Role of the Woman Physician, 1915-1990.” Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association 45.5 (1990): 165-180.

- —, Elizabeth Fee, and Manon Parry. “Introduction.” Women Physicians and the Cultures of Medicine. Ellen More, Elizabeth Fee and Manan Parry, eds. John Hopkins UP, 2009.

- Moss, Beverly J. A Community Text Arises: A Literate Text and a Literate Tradition in African-American Churches. Hampton P, 2003.

- Mueller, Derek. “Grasping Rhetoric and Composition by Its Long Tail: What Graphs Can Tell Us about the Field’s Changing Shape.” College Composition and Communication 64.1 (2012): 195-223.

- —. Network Sense: Methods for Visualizing a Discipline. WAC Clearinghouse, 2017.

- Palmeri, Jason and Ben McCorkle. “A Distant View of English Journal, 1912-2012.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 22.2 (2017).

- Pough, Gwendolyn D. Check It While I Wreck It: Black Womanhood, Hip-Hop Culture, and the Public Sphere. Northeastern UP, 2015.

- Riley, Marilyn Griggs. High Altitude Attitudes: Six Savvy Colorado Women. Big Earth Publishing, 2006.

- Root, Eliza H. “Editorial: The Last Year of the Century.” Woman’s Medical Journal 8.1 (January 1899): 9-10.

- Royster, Jacqueline Jones. Traces of a Stream: Literacy and Social Change Among African American Women. U of Pittsburgh P, 2000.

- Royster, Jacqueline Jones, and Gesa E. Kirsch. Feminist Rhetorical Practices: New Horizons for Rhetoric, Composition, and Literacy Studies. SIU Press, 2012.

- —. “Social Circulation and Legacies of Mobility for Nineteenth Century Women.” Rhetoric, Writing, and Circulation. Eds. Laurie E. Gries and Collin Gifford Brooke. Utah State UP, 2018. 170-188.

- Ryan, Kathleen, Nancy Myers, and Rebecca Jones. Rethinking Ethos: A Feminist Ecological Approach to Rhetoric. Southern Illinois UP, 2016.

- Savitt, Todd L. “The Journal of the National Medical Association 100 Years Ago: A New Voice of and for African American Physicians.” Journal of the National Medical Association 102.8 (August 2010): 734-744.

- Skinner, Carolyn. Women Physicians and Professional Ethos in Nineteenth-Century America. Southern Illinois UP, 2014.

- Stratton, Mary Reed. “Social Evil and its Consequences.” Woman’s Medical Journal 29. 4 (April 1919): 62-65.

- Vandervall, Isabella. “Some Problems of the Colored Woman Physician.” Woman’s Medical Journal 27.7 (July 1917): 156-158.

- Ward, Thomas J. Black Physicians in the Jim Crow South. U of Arkansas P, 2003.

- Wells, Susan. Out of the Dead House: Nineteenth-Century Women Physicians and the Writing of Medicine. U of Wisconsin P, 2001.

- “Women Serving Abroad.” Woman’s Medical Journal 29. 7 (July 1919): 152.

Appendix

Fig. 6. The WMJ 1900 volume social network.

Fig. 7. The WMJ 1910 volume social network.

Fig. 8. The WMJ 1919 volume social network.