CHAPTER TWO

Motivational Scaffolding's Potential for

Inviting Transfer in Writing Center Collaborations

TRANSFER OF LEARNING IN THE WRITING CENTER

Kathy Rose

Dixie State University

Jillian Grauman

College of DuPage

A writing center can be an effective site for writing transfer when conditions are right, but transfer scholars have highlighted the complexity of the factors that influence these conditions. One such factor is the influence of writers' dispositions: generative dispositions that can positively impact an individual's ability to learn and disruptive dispositions that will negatively impact an individual's development (Bronfenbrenner and Morris). A writer's dispositions, defined by Dana Lynn Driscoll and Jennifer Wells as "qualities that determine how learners use and adapt their knowledge" toward their writing task, are "critical to success in transfer of learning." Driscoll and Wells describe specific, generative dispositions that influence transfer, including self-efficacy and self-regulation. If students believe they can be successful (self-efficacy) or if they can effectively adapt to the requirements of the specific situation (self-regulation), they are more likely to transfer their learning successfully. Elizabeth Wardle also connects disposition and transfer in her discussion of problem-solving and answer-getting dispositions. She says problem-solvers actively seek solutions to challenges, recognizing that current challenges might not look exactly like what they have encountered in the past; answer-getters look for specific answers to challenges and then move on without mindfully making many connections to past or future challenges. Answer-getting dispositions are sometimes indicated by conversations heard in writing centers.

Take, for example, these questions a writer in our school's writing center asked: "How would you want me to put that, like, in words?" and "You said this paragraph was good, right?" Questions like these can imply a lack of self-efficacy and/or a lack of self-regulation. They can imply that the writer wants the tutor to answer specific questions that will make the writing successful. Perhaps the writer has prior knowledge or experience that should "kick in" and make this session more collaborative, but these questions do not indicate a willingness or ability to do that. How, then, can writing centers facilitate self-efficacy and self-regulation? Many tutors likely use intuitive strategies that enable these generative dispositions, but tutors who are trained to encourage these dispositions can more effectively and purposefully enable transfer.

Given the great potential for transfer in the writing center, and our own experiences noticing potential moments of transfer while tutoring, we used Jo Mackiewicz and Isabelle Thompson's coding framework (Talk) to analyze six video-recorded tutoring sessions and identify moments where self-efficacy and self-regulation are evident. We wanted to see which strategies seem to encourage and support these generative dispositions in these instances. Knowing that tutors are likely using motivational strategies intuitively, our goal is to highlight how tutors can purposefully support transfer. By identifying and teaching specific strategies that are helpful to self-efficacy and self-regulation, we can create a better transfer-enabling environment in writing centers.

Literature Review: Motivation, Politeness, and Scaffolding

Many factors influence a writer's readiness and ability to transfer learning (e.g., Bergmann and Zepernick; Slomp). Motivation can encourage generative dispositions. According to Pietro Boscolo and Suzanne Hidi, learners who are motivated to work on a project are also likely to have high self-efficacy and self-regulation. In "Motivational Scaffolding, Politeness, and Writing Center Tutoring," Mackiewicz and Thompson examine politeness strategies tutors use to develop rapport and motivate student writers. The authors explain that tutors' negative politeness strategies, like being indirect or apologizing, soften directives and "do not threaten students' motivation to participate actively in collaboration" ("Motivational" 42). An example of this would be "You could do this" rather than "Do this." Negative politeness encourages agency and offers writers freedom to "self-regulate" their learning. Mackiewicz and Thompson also explain the importance of positive politeness strategies to motivational scaffolding. Positive strategies include offering praise, being optimistic, and joking, which can put writers at ease (if tutors and students both understand context) and create a shared feeling of sociality. Mackiewicz and Thompson describe how motivation "influences and is influenced by" self-efficacy and self-regulation and that motivated writers will participate more actively in dialogue, thus allowing tutors to individualize their instruction ("Motivational" 44). We extend the work of Mackiewicz and Thompson by using their framework and arguing that the motivational scaffolding strategies we see in our small-scale study can encourage writers to take on transfer-enabling dispositions.

The Mackiewicz and Thompson framework (Talk) allows for close attention to tutor talk and linguistic choices because linguistic choices like politeness strategies can impact student motivation. Engagement is another linguistic choice the framework allows us to see. Engagement, according to linguist Ken Hyland, is important for establishing a relationship with an audience (in this case, tutor with writer). Hyland shows that questions, personal asides, shared knowledge, or the use of inclusive pronouns like "we" can, among other moves, encourage engagement (177). These moves towards building engagement can encourage writers as they progress from listening, to actively participating, to taking ownership of their projects. Such moves can provide scaffolding for a writer in developing self-efficacy and self-regulation. The term "scaffolding" is commonly used in relation to cognitive learning opportunities. But in Mackiewicz and Thompson's (Talk) framework, motivation is considered a separate, important type of scaffolding, along with cognitive and instructional scaffolding. So, as tutors provide instructional and cognitive scaffolding, how can they also provide motivational scaffolding?

The Mackiewicz and Thompson framework (Talk) allows for close attention to tutor talk and linguistic choices because linguistic choices like politeness strategies can impact student motivation. Engagement is another linguistic choice the framework allows us to see. Engagement, according to linguist Ken Hyland, is important for establishing a relationship with an audience (in this case, tutor with writer). Hyland shows that questions, personal asides, shared knowledge, or the use of inclusive pronouns like "we" can, among other moves, encourage engagement (177). These moves towards building engagement can encourage writers as they progress from listening, to actively participating, to taking ownership of their projects. Such moves can provide scaffolding for a writer in developing self-efficacy and self-regulation. The term "scaffolding" is commonly used in relation to cognitive learning opportunities. But in Mackiewicz and Thompson's (Talk) framework, motivation is considered a separate, important type of scaffolding, along with cognitive and instructional scaffolding. So, as tutors provide instructional and cognitive scaffolding, how can they also provide motivational scaffolding?

If we look at how the concept of scaffolding applies to cognitive issues, we can use similar thinking about motivational scaffolding. Sadhana Puntambekar and Roland Hubscher describe scaffolding as occurring in four stages, with each step lessening the interactions between teacher and learner: first, collaborative development of a learning goal; second, ongoing diagnosis of the learner's understanding; third, dialogic and interactive instruction; and fourth, fading—where the expert lessens formal support because the learner has come within a reasonable range of doing the task independently (2-3). But to reach this fading stage, learners cannot be passive vessels. Learners must actively form a bridge between a teacher's support and their own control of their learning process, a form of self-scaffolding that indicates metacognition, a key transfer-enabling activity (Holton and Clark 128). Indeed, self-scaffolding is an important step in building self-regulation. For instance, a writer could listen to a tutor's suggestion for a way to improve a thought but then come up with a suggestion not offered by the tutor. This behavior demonstrates active participation and self-regulation and implies a problem-solving mindset.

Method

To identify specific strategies that are helpful to student self-efficacy and self-regulation, we conducted an IRB-approved study in which we video-recorded, transcribed, and coded writing center sessions. Participating tutors and students signed informed consent documents. We used a video camera to video-record 35 sessions over two weeks in the Spring of 2015; the room in which we placed the video camera was typically used for writing center sessions. Because of the size of the room, only one appointment could happen at a time, ensuring that only one session was being recorded and that the writing center's typical practices were not disrupted. All videos (and subsequent transcripts and analysis) were stored in password-protected cloud storage. We also collected surveys from the clients, which asked for their demographic information and their comfort and satisfaction with their writing center appointment. Of the sessions we recorded during the two-week period, all tutors were native speakers of English and four clients identified themselves as speaking English as a second language.

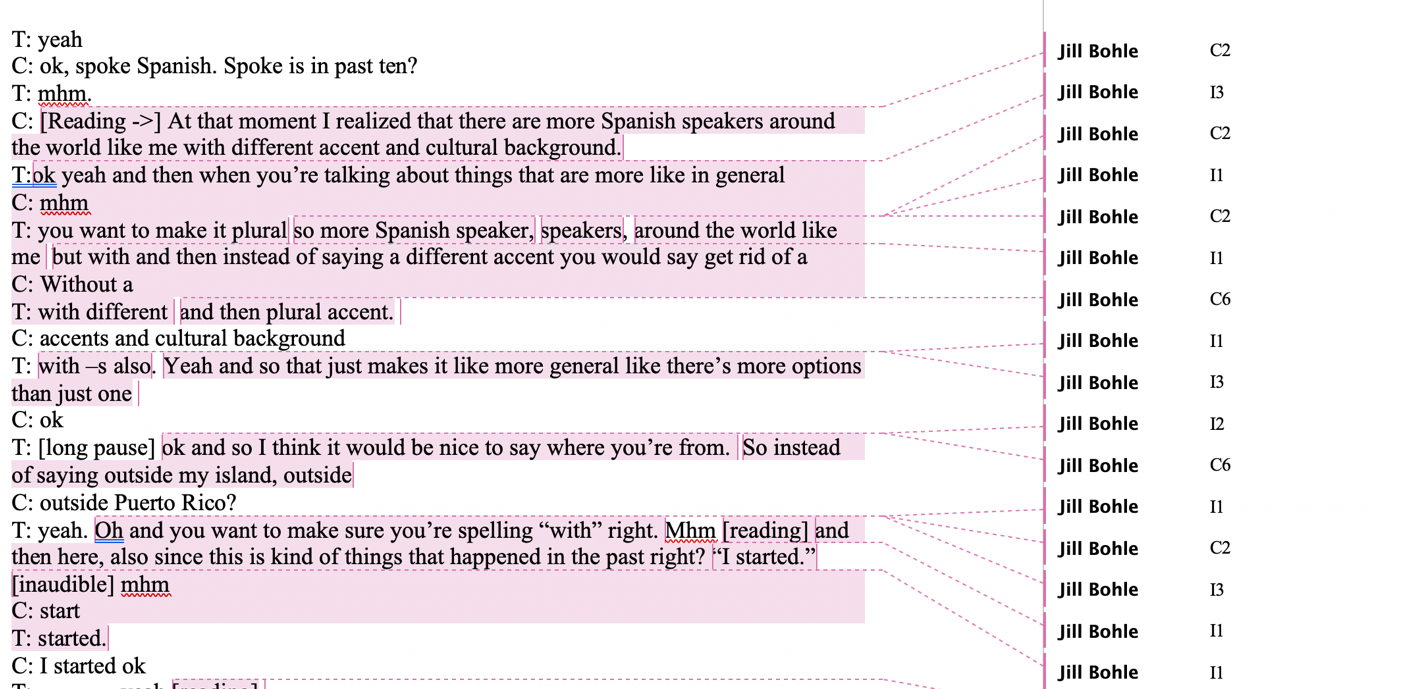

For this small-scale study, we chose six sessions to analyze using the Mackiewicz and Thompson (Talk) framework for motivational scaffolding. In response to Mackiewicz and Thompson's (Talk) call for more research that intentionally includes second-language writers, we randomly selected three sessions with clients who identified their native language as other than English and three with clients who identified English as their native language. After having the sessions transcribed by an IRB-approved colleague, we normed our coding procedure by coding the first two sessions together. We compared individual coding on a third session, negotiating differences to come to a consensus. As we operationalized the codes, we determined that our unit of analysis was a "topic episode," meaning a single topic of conversation (Mackiewicz and Thompson, Talk). We also determined that we would only assign one code to each topic episode, although multiple codes might apply simultaneously. We differentiated pumping questions, which are asked to inspire thinking, from information-gathering questions or what we called "housekeeping questions" (like questions about the writing assignment, due dates, and the student's prior experience with the writing center). See figure 1 for a screenshot of a typical page of coding.

|

| Figure 1. Typical Example of a Coded Transcript Page. |

After our norming and analysis process, we did not feel that our coding was adequately aligned. To enhance our inter-coder reliability and check any tendencies toward idiosyncrasy, we also asked a third person to code our transcripts. We shared our operationalized decisions and normed our coding process by coding one session collaboratively before working independently. (See Appendix A for coder instructions.) After the third coder completed the remaining sessions, we compared his work with ours, discussing and negotiating differences between his coding and ours. Having completed the coding process, we used a grounded theory approach to notice and then focus further on interesting moments, such as those times where we saw tutors fading or a shift of power occurring, where the client took an active role in the session, acting like a fully-engaged collaborator.

The Mackiewicz and Thompson motivational scaffolding framework (Talk) identifies the following five strategies tutors may use (See Appendix B for coding labels and definitions we used for these strategies.):

- showing concern

- praising

- reinforcing student writers' ownership and control

- being optimistic or using humor

- giving sympathy or empathy. (Talk 58)

In our study, we focused on identifying these motivational strategies while acknowledging their vital connection with the other strategies, particularly with cognitive scaffolding.

Results: Tools for Building Bridges

The following examples from our transcripts illustrate our results. Each of the five motivational strategies from the Mackiewicz and Thompson (Talk) framework appear in the data.

Showing Concern

In our selected sessions, tutors who showed concern had a positive impact. When Mackiewicz and Thompson (Talk) describe motivational strategies, they note that the question, "Does that make sense?" is a show of concern (43), and we see that in this example. Here the tutor and writer are discussing the differences between analyzing and summarizing. Then, the tutor ends an explanation of what analysis is by showing concern. After a moment, the writer responds fully to the tutor's question (Listen to Transcript 1):

Tutor: ... Do both of those make sense to you?

Writer: Mmm. I think so.

Tutor: Ok.

Writer: Excuse me? Um ah, I think both of those... analyze this. Is there a way we can ask something about um how people um become interesting to study something about swords...?

Although this writer does not initially respond to the tutor's show of concern, the writer does voice a question fairly quickly, asking to spend more time on the topic, thus seeming to exhibit self-regulation. The writer demonstrates the ability to self-regulate her learning by taking control of the next topic of discussion. It's important that tutors encourage self-regulation by allowing time for writers to decide what to work on. The motivational moves of praising and showing concern offer such an opportunity.

Although this writer does not initially respond to the tutor's show of concern, the writer does voice a question fairly quickly, asking to spend more time on the topic, thus seeming to exhibit self-regulation. The writer demonstrates the ability to self-regulate her learning by taking control of the next topic of discussion. It's important that tutors encourage self-regulation by allowing time for writers to decide what to work on. The motivational moves of praising and showing concern offer such an opportunity.

Praising

Before this exchange, the writer and tutor are discussing how to organize a paragraph that incorporates different points of view on the writer's topic, and the tutor offers some instruction. The tutor's praise in the following example seems to encourage self-regulation (Listen to Transcript 2).

Tutor: Yeah, but I think the information is really good. Um yeah, really interesting, point of view I guess.

Writer: Yeah um, I had a question. So I need like four sources and like five page long essay. So, I was thinking if I make like the first paragraph after my thesis statement about, just like the, uh, what he disclosed, cuz there is more of it and then start with the, different opinions, how would I like, arrange it in my essay with the thesis statement and everything?

Reinforcing Writer Ownership and Control

Reinforcing agency is another strategy in the Mackiewicz and Thompson (Talk) framework. By reminding writers that they are in charge of their own writing, "tutors assert that the student writer ultimately makes the decisions" (Mackiewicz and Thompson, Talk 58). This move often appears when writers determine what to work on, as in this excerpt from our study:

Tutor: We have an hour. Um we can look at some more of the grammar and making sure your flow and organization makes sense, or we can look at citations first. Which one would you like to do, it's kind of up to you.

Writer: Um maybe citations.

By asking for attention to citations, the writer establishes a priority for the session, corresponding to Puntambekar and Hubscher's first scaffolding stage. Tutors can also reinforce writer ownership and control by discussing different revision options, which is further along the scaffolding continuum than establishing a priority for the session.

The next excerpt shows the tutor and writer have been discussing how to improve the hook in the introduction. Currently, the writer has a statistic, but the tutor suggests using a story. They collaboratively compose a possible first sentence, the tutor reinforces the writer's control over the paper, and then, the writer comes up with an idea combining the statistic and the story (Listen to Transcript 3):

Tutor: That's another way you could go about it. Is there any one way which really appeals to you?

Writer: Um, not really.

Tutor: Okay.

Writer: Maybe—I mean its sports as a whole...

The writer then talks through ideas about the story suggestion but finally stops to ask:

Writer: Could you do both?

Tutor: You could do both.

With that encouragement from the tutor, the writer is off and running, combining the story with the statistic. Even though the tutor's initial move ("Is there any one way which really appeals to you?") of reinforcing agency is not immediately followed by the writer making a choice, the tutor's motivation encourages the writer to think it through. Ultimately, the writer makes a decision that differs both from the tutor's suggestion and the writer's original draft—an indication of productive collaboration.

Being Optimistic, Using Humor, or Giving Sympathy/Empathy

Mackiewicz and Thompson identify "Being optimistic or using humor" as another motivational strategy, one that can help reduce writers' anxieties and build confidence (Talk 43), thus encouraging self-efficacy (Talk 128). Positivity efforts commonly occur early in sessions where tutors quickly create feelings of rapport and solidarity, often combined with empathy, one of the strategies Mackiewicz and Thompson identify (Talk 58).

In one session, the tutor's use of humor—another positive politeness technique—helps develop a feeling of social approval. In joking about commas and Shakespeare, the tutor creates a social connection. Then we hear the tutor being optimistic by offering support and praise. These strategies all worked together productively. In fact, when positivity, praise, and empathy occur within the same session, overly critical writers may show an increase in the level of comfort with their work. For example, in this same session we hear frequent positivity (Listen to Transcript 4):

Student: There's gonna be grammatical errors probably because it's a rough draft.

Tutor: It's a rough draft; everybody does that.

Early in this session, this writer, asking for help with a list of things, expresses timidity, and the tutor's quick response demonstrates empathy. Then, as the writer begins reading the work aloud, the tutor praises it before saying anything else and continues to sprinkle expressions of praise throughout their conversation. After creating this environment through humor, empathy, and praise, the tutor offers more direct instruction. Then, the writer begins actively participating. Although the writer's progress is not linear, the tutor effectively assesses the writer's needs and offers motivational scaffolding throughout the conference.

As the session progresses, the writer uses language indicating self-efficacy and self-regulation (Listen to Transcript 5):

Tutor: ...give an example of something

Writer: Yeah

Tutor: like that 'cause I agree that I think you need a little bit more on there, and usually with, um, these kinds of sentences that just kind of feel awkward, the organization is kind of the key

Writer: Mmhmm

Tutor: to that, so just kind of switching things around seeing if these words are gonna, uh, are gonna work or that kind of thing, uh

Writer: we need to use some, uh, quotes in here probably

Tutor: Yeah

Writer: So that might be a good place to like, be able to use a quote

Tutor: do a quote...

In this exchange, the writer is a collaborative peer using an inclusive "we" and offering a new idea (i.e., putting in a quotation). So, the writer momentarily takes charge of the conversation while the tutor fades, simply agreeing with and repeating what the writer says. Ultimately, the tutor's motivational scaffolding opens up a space for cognitive and instructional scaffolding to be more effective, and, ideally, the self-efficacy the writer develops will carry over into other writing projects.

In this exchange, the writer is a collaborative peer using an inclusive "we" and offering a new idea (i.e., putting in a quotation). So, the writer momentarily takes charge of the conversation while the tutor fades, simply agreeing with and repeating what the writer says. Ultimately, the tutor's motivational scaffolding opens up a space for cognitive and instructional scaffolding to be more effective, and, ideally, the self-efficacy the writer develops will carry over into other writing projects.

Motivational and Cognitive Strategies Work Together For Transfer

It is simplistic and unrealistic to isolate completely motivational scaffolding from cognitive and instructive scaffolding. Mackiewicz and Thompson (Talk) classify acts of questioning as a cognitive scaffolding strategy. They also say acts of questioning can be "models for students' subsequent self-questioning, a process important for self-regulation of learning" (Talk 34). Hyland sees questioning as motivational or a method to promote engagement (177). We see questions being used to good effect both motivationally and cognitively. Our study supports Mackiewicz and Thompson's suggestion (Talk 37) that motivational and cognitive strategies are interrelated. For instance, in some cases, writer self-efficacy seems to increase in response to effective questions combined with motivational strategies.

In the following example from our study, the session gradually progresses toward increased writer involvement. Near the beginning of the session, the tutor suggests that a sentence seems "too short." While the writer agrees, she does not actively participate in crafting a new one. The writer seems to be waiting for the tutor to supply what should be said. The tutor then asks a pumping question to foster self-efficacy:

Tutor: How do you think we can combine that into a more complex sentence that you can combine all of that information?

The tutor's polite refusal to provide quick answers corresponds to Puntambekar and Hubscher's second stage of scaffolding, where tutors provide calibrated support until they are sure writers can reach the next level of expertise. Only after the writer attempts to combine the short sentences does the tutor offer instructional strategies. This pattern recurs throughout the session; we see the writer alternating from someone who laughs nervously and says things like, "I don't know—I can't," to someone who actively works towards solutions for challenges and even interrupts to finish the tutor's sentences.

Terese Thonus, based on her research into effective writing center conferences, suggests that interactional features like tutors and writers finishing each other's sentences signal a successful conference. We noted the feel of active collaboration evidenced by these interruptions. In this same session, the writer and tutor interrupt each other and finish each other's sentences as they search for better words and phrases for the writer's project. In the following example of this, we have formatted the transcript to show where utterances fall in relation to each other:

Tutor: and you've gotten everything in one sentence and the reader doesn't have to stop

Writer: Yeah

Tutor: and break for the ideas

Writer:Mmhmm

Tutor: Mmhmm. So, um

Writer: So then actually I should [indecipherable] in and put

Tutor:Yeah

Writer: this again

Tutor:I think I think yeah after a sentence like that because that's it's pretty factual um

Writer: Mmhmm

Tutor: it might be a good spot to have your

Writer:OK

Tutor:um citation

In this exchange, the writer and the tutor are creating a thought collaboratively—it looks as if they are in synch and reading each other's thoughts. Active writer involvement, like in this session, indicates self-regulation and self-efficacy. The writer seems to be making cognitive gains through the strategy of pumping questions. But the motivational scaffolding the tutor employs, working in concert with the pumping questions, is the key to their effect. The tutor does not do the work the writer can do but uses techniques such as the inclusive pronoun "we" with plenty of praise and concern to encourage self-efficacy. Such moves make it easier for writers to accept cognitive scaffolding that enables them to take charge of their own writing.

In sum, when we examine tutors' conversations in our transcripts, we see writers in various stages of Puntambekar and Hubscher's scaffolding continuum. Tutors use strategies such as praising or showing concern, sometimes in combination with other strategies, and writers respond in ways that suggest increased self-efficacy and/or self-regulation. In some conferences, motivational scaffolding seems to influence a writer's disposition fairly quickly, while at other times generative dispositions unfold more gradually. The most productive moments are conversations where the writers actively engage in collaborative dialogue, demonstrating self-efficacy and self-regulation, rather than letting or expecting tutors to lead. In these moments, the motivational scaffolding the tutors use seems to create an environment encouraging active engagement.

So, after tutors use motivational scaffolding, the data reveal two general trends: 1) writers may demonstrate increased self-regulation through steering the direction of their writing center session and 2) writers may demonstrate increased self-efficacy. Writers sometimes steer the direction of their sessions by asking questions (prompted or not), expressing a preference about what they do during the session, and starting new topic episodes. Sometimes they engage with the tutors in an interchange where they interrupt and talk over each other. Of course, this is not always a linear progression. Clients still defer to tutors when they do not feel that they have the expertise or when tutors offer solutions too readily. As we discuss above, the tutor who did not provide quick answers provided appropriate scaffolding for a client who demonstrated passive participation, even after some confidence-building topic episodes. But for the most part, what we observed was that self-regulatory behaviors, as well as language that implies confidence, arise when tutors use the motivational scaffolding strategies of praising, showing concern, and reinforcing the writer's ownership and control.

Limitations

Although encouraging, this pilot study has several limitations. First of all, any coding of dispositions or motivations is unavoidably subjective in many respects. While we used consensus to code areas of disagreement in our coding process, a rigorous content analysis approach that establishes inter-coder reliability, complete with an initial and final inter-coder reliability check, would likely yield more reliable, though still not completely objective, results. Further research could determine whether the coding scheme needs to be fine-tuned. For instance, we saw one motivational strategy, M3, which is reinforcing ownership and control, differently. One of us saw many more instances of tutors giving clients control over their own work. Also, our third rater interpreted humor differently than we did, even after we provided him operationalized codes.

It would also be beneficial to gain insight into writers' perceptions about their own self-regulation and self-efficacy. Additionally, the study examined writers only one time without noting whether the writer was new to the writing center or had visited before. Further research could look at multiple sessions with the same writer or include interviews or focus sessions about how their session(s) helped them approach other writing situations.

Implications for Writing Center Pedagogy

Showing concern, praise, reinforcing ownership and control, and positivity can all empower student writers, bolstering self-efficacy. These strategies open up opportunities for writers to ask questions and initiate new topics, both of which are examples of self-regulating dispositions. These sessions indicate an environment where writers feel confident about taking charge of their writing rather than expecting someone to tell them what to do. By intentionally using these strategies, tutors can help hesitant or less confident writers in building these transfer-prone dispositions in a relatively low-stakes space.

Showing concern, praise, reinforcing ownership and control, and positivity can all empower student writers, bolstering self-efficacy. These strategies open up opportunities for writers to ask questions and initiate new topics, both of which are examples of self-regulating dispositions. These sessions indicate an environment where writers feel confident about taking charge of their writing rather than expecting someone to tell them what to do. By intentionally using these strategies, tutors can help hesitant or less confident writers in building these transfer-prone dispositions in a relatively low-stakes space.

Writers who leave conferences with increased self-efficacy and self-regulation can more effectively ask future questions and explore future problems (Wardle) as they build bridges of self-regulation (Holton and Clark). So, tutor training should emphasize the importance of using motivational strategies to set the stage for a more engaging, collaborative relationship. Motivational scaffolding, a valuable technique in writing center conferences, requires that tutors assess the learner's needs and employ an array of strategies for enabling confidence and encouraging learning. Ongoing sessions with writers could further strengthen such gains.

One way in which tutor training might encourage motivational scaffolding techniques is through collaborative and/or individual coding of recorded writing center sessions. As they watch their own recorded sessions, tutors might look specifically for pumping questions and for motivational scaffolding moves like praise, positivity, and showing concern. In addition, they could examine their word choices, such as inclusive pronoun usage. Tutors could then examine what happened around these moves: Does the writer determine the next topic they discuss? How actively does the writer participate? Certainly, tutors need to discover their own style and recognize how to make these moves naturally; they also need to recognize that writers differ in their responses to motivational scaffolding. However, it would be valuable for tutors to reflect on their practices and consider how consistently and intentionally they use motivational scaffolding, as well as what they might try in the future.

Works Cited

Bergmann, Linda S., and Janet Zepernick. "Disciplinarity and Transfer: Students' Perceptions of Learning to Write." WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 31, no.1-2, 2007, pp.124-49.

Boscolo, Pietro, and Suzanne Hidi. "The Multiple Meanings of Motivation to Write." Studies in Writing: Writing and Motivation, edited by Suzanne Hidi and Pietro Boscolo, Elsevier, 2007, pp. 1-14.

Bronfenbrenner, Urie, and Pamela A. Morris. "The Bioecological Model of Human Development." Handbook of Child Psychology, edited by Richard M. Lerner and William Damon, vol. 1, Wiley, 2006, pp. 793-828.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Jennifer Wells. "Beyond Knowledge and Skills: Writing Transfer and the Role of Student Dispositions." Composition Forum, vol. 26, Fall 2012, compositionforum.com/issue/26/beyond-knowledge-skills.php

Holton, Derek, and David Clark. "Scaffolding and Metacognition." International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, vol. 37, no. 2, 2006, pp.127-43.

Hyland, Ken. "Stance and Engagement: A Model of Interaction in Academic Discourse." Discourse Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2005, pp. 173-92.

Mackiewicz, Jo, and Isabelle Thompson. "Motivational Scaffolding, Politeness, and Writing Center Tutoring." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 33, no. 1, 2013, pp. 38-73.

---. Talk About Writing: The Tutoring Strategies of Experienced Writing Center Tutors. Routledge,

2015.

Puntambekar, Sadhana, and Rowland Hubscher. "Tools for Scaffolding Students in a Complex Learning Environment: What Have We Gained and What Have We Missed?" Educational Psychologist, vol. 40, no. 1, 2005, pp. 1-12.

Slomp, David H. "Challenges in Assessing the Development of Writing Ability: Theories, Constructs and Methods." Assessing Writing, vol. 17, 2012, pp. 81-91.

Thonus, Terese. "Tutor and Student Assessments of Academic Writing Tutorials: What Is 'Success'?" Assessing Writing, vol. 8, no. 2, 2002, pp. 110-34.

Wardle, Elizabeth. "Creative Repurposing for Expansive Learning: Considering 'Problem-Exploring' and 'Answer-Getting' Disposition in Individuals and Fields." Composition Forum, vol. 26, Fall 2012. compositionforum.com/issue/26/creative-repurposing.php.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the advice of Dr. Jo Mackiewicz on this project. We also appreciate draft feedback we received from Dr. Barbara Blakely and Dr. Christa Tiernan. Lastly, we thank Dale Grauman for his willingness to be a rater during a long, intense coding process.

BIOS

Kathy Rose is an instructor at Dixie State University. She began this project when she was earning her PhD and working in the Iowa State University Writing and Media Center. Her research interests include transfer, reflection, and the transition of dual enrollment high school students to college.

Jillian Grauman is an Assistant Professor of English at College of DuPage. She holds a Ph.D. in Rhetoric and Professional Communication from Iowa State University and an MA in Rhetoric and Composition from Washington State University. Her research interests include writing program administration and teacher response to student writing.