CHAPTER SEVEN

Transfer(mation) in the Writing Center:

Identifying the Transformative

Moments that Foster Transfer

TRANSFER OF LEARNING IN THE WRITING CENTER

Cynthia Johnson

University of Central Oklahoma

As discussions of transfer have spread from educational psychology to writing studies, scholars have identified writing centers as spaces uniquely situated to facilitate students' transfer processes. Julie Hagemann suggests "a writing center tutor often has a broader view of students' writing than any one of his teachers" (122). She notes, however, that many transfer studies place a limited focus on diachronic writing transfer, or transfer from one context to another, later context. Writing centers, she argues, can also help researchers better understand synchronic transfer, or transfer between several different courses within a single semester. Continuing this discussion, Rebecca Nowacek recognizes the complex role of writing consultants as handlers, helping writers to build connections between contexts, as well as agents of integration, or learners who are themselves transferring between contexts. More recently, Bonnie Devet and Dana Lynn Driscoll each discuss the role of transfer in the writing center, focusing particularly on writing consultants' ability to transfer their writing center skills throughout and beyond their experiences as consultants.

Yet much work remains in understanding how transfer happens through, within, and because of writing centers, especially in ways that address transfer's messiness and variability. As we work to understand transfer in our centers, we must resist reductive understandings of the concept, such as that of a learner carrying static knowledge between two discrete contexts. Rather, a growing point of consensus is that transfer is a process of transformation: diverse learners transform through new knowledge and experiences (Beach; Smart and Brown); knowledge transforms to meet the needs of new activity systems (Wardle; Reiff and Bawarshi; DePalma and Ringer); and as a result, the contexts themselves are transformed. Transfer is not a clear-cut moment of learning and application but a series of smaller transformations that allow learners to perform in and interact with new contexts. As such, writing centers as facilitators of transfer must first be understood as facilitators of transformation. Without this more nuanced lens, we risk overlooking many subtle moments of learning and connection-making that occur in our centers.

This essay considers both the ubiquity of and potential for transformation in writing centers. I draw on my observations as an assistant director of a disciplinary center, which also acts as a WID program in a mid-sized, public university's School of Business. I provide a form of practitioner lore, which I hope will serve as a model for other writing center directors and staff to reflect on their roles in facilitating transformation in their own unique spaces. In the following, I briefly synthesize scholarship on transfer as transformation; I draw from three scenarios to provide examples of transformation and to model the types of situated reflection I hope readers will perform; and in conclusion, I pose a series of questions and an activity to help practitioners engage in such reflection in their own centers. This reflection gives writing consultants more nuanced understandings of their role and influence in the center and further interweaves discussions of transfer and transformation. While I do not suggest we abandon the term transfer, we must resist some of the reductive connotations it has assumed. Attention to the ongoing transformations of learners, knowledge, and contexts provides us one way of doing so.

Transfer as Transformation

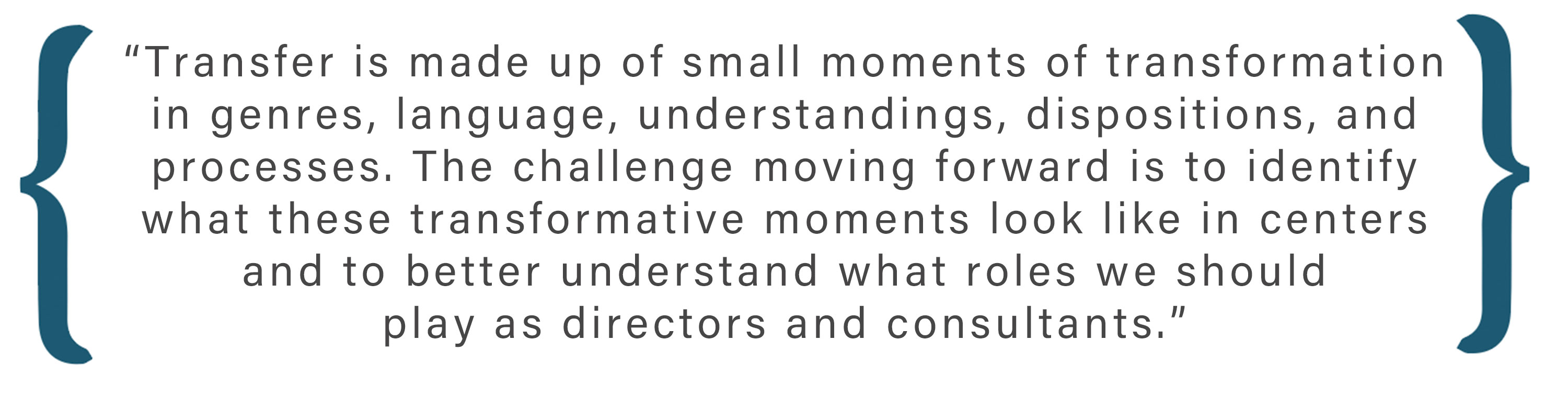

Writing studies scholars have long paired and critiqued transfer with notions of transformation. A learner does not carry static knowledge to distinct contexts; rather, transfer is a continuous process of movement and change. Educational psychologist King Beach suggests we "move beyond the transfer metaphor," proposing the term generalization to describe "how we experience continuity and transformation in becoming someone or something new" and "how we learn new tasks and problems" (102). Graham Smart and Nicole Brown further suggest the phrase transformational learning is more appropriate than transfer of learning, concluding that, rather than transferring knowledge, the professional writing students they studied were themselves transforming. That is, they were developing into experts, which made them better prepared to negotiate later contexts with or without the direct application of prior knowledge. Elizabeth Wardle also argues that "focusing on a limited search for 'skills' is the reason we do not recognize more evidence of 'transfer'; we are looking for apples when those apples are now part of an apple pie" (69). She then adopts Beach's term, generalization.

Many writing studies scholars have further responded with their own analogies for how knowledge and learners transform as part of the transfer process. Mary Jo Reiff and Anis Bawarshi, in categorizing their students as boundary-guarders and boundary-crossers, recognize students for their willingness to transform genre knowledge. That is, boundary-guarders resist the transformation of genres, ineffectively forcing previously learned genres into new situations. Boundary-crossers, in contrast, are more willing to deconstruct, remix, and adapt genres to new contexts. For instance, a boundary-guarder might force ideas into a previously learned five-paragraph format, whereas a boundary-crosser might use the format more flexibly, pulling elements that are useful and applicable (such as an introduction, thesis statement, and/or conclusion) without forcing ideas into five neat paragraphs. More recently, Bawarshi has also proposed a teaching about transfer approach to first-year composition, which hinges on Henry S. Broudy's notion of knowing with. This model suggests transfer is not based on a direct application of prior knowledge and experiences, but rather on "associating, interpreting, adapting, and translating prior knowledge to help us perform new tasks in new contexts" (90). In this model, a student might not apply a previously learned genre directly to a new context, but their previous understanding of and experience with that genre might still help them to navigate new rhetorical situations more effectively.

Nowacek also moves beyond a "mere application" model of transfer and introduces the term recontextualization, stating, "[T]ransfer understood as recontextualization recognizes that transfer is not only mere application; it is also an act of reconstruction" (25). While Nowacek does not deny that application is a form of transfer, she argues that we must also consider the ways knowledge is reconstructed in new contexts. Likewise, Michael-John DePalma and Jeffrey Ringer argue, "[D]iscussions of transfer in L2 writing and composition studies have focused primarily on the reuse of past learning and thus have not adequately accounted for the adaptation of learned writing knowledge in unfamiliar situations" (135). They then coin the term adaptive transfer, which they describe as dynamic, idiosyncratic, cross-contextual, rhetorical, multilingual, and transformative. Lastly, Kathleen Yancey, Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak also conceptualize models for how writers integrate prior knowledge into new contexts: through assemblage, in which the writer merely attaches new knowledge to prior knowledge (e.g., forces their ideas into a five-paragraph format); through remix, in which the writer integrates both new and prior knowledge into their mental schema (e.g., adapts both the five-paragraph format and their ideas to find an effective arrangement); and through critical incident, in which the writer is unsuccessful in a new task and must reconsider their approach altogether (e.g., finds that the five-paragraph format is at odds with what is being asked of them).

What all of these theories–summarized in Table 1–demonstrate is that transfer is not simply the reuse or application of prior knowledge. Transfer is made up of small moments of transformation in genres, language, understandings, dispositions, and processes. The challenge moving forward is to identify what these transformative moments look like in centers and to better understand what roles we should play as directors and consultants.

Table 1

Views of Transfer Involving Transformation

Moments of Transformation in the Writing Center

In the following, I use these theories of transformation (Table 1) to analyze moments I have observed in my writing center. A lens of transformation foregrounds how writing centers regularly contribute to transfer in ways that might not be immediately identifiable as transfer. These observations took place in the Howe Writing Initiative (HWI), where I worked as one of three assistant directors. Unlike a university-wide writing center, the HWI serves and is located within Miami University's Farmer School of Business. It was founded through a generous donation by Miami University alumni, Roger and Joyce Howe. The HWI director has historically been a faculty member from the Department of English; the three assistant directors are doctoral students in the Department of English; and the undergraduate consultants consist of 15-20 students majoring in business disciplines. We hold approximately 2,500 consultations a year with business majors working on writing and speaking projects. The director and assistant directors balance their time working with undergraduate consultants and writers while helping business faculty to integrate writing into their classes.

|

| Figure 1. The HWI Director visits a marketing class to discuss effective presentation strategies. Photo by Tim R. Holcomb. |

The HWI also holds partnerships with several business classes, in which the directors facilitate writing and speaking workshops in the classes, and instructors give students incentives to visit the HWI, such as requiring it as part of the assignment or offering extra credit. For these partnerships, the undergraduate consultants are provided the assignment sheets in advance, as well as occasional notes about the genre or assignment from the instructors. While the HWI consultants do not act as instructors, nor do they serve as fellows for specific classes, they often act in a more specialist role than they would in a university-wide writing center. As part of their consultant training, we discuss specific business writing principles, such as the "6 Cs of Business Communication": consideration, clarity, conciseness, coherence, correctness, and confidence. We also discuss the purpose and conventions of common business genres, such as cover letters, emails, memos, executive summaries, and proposals, as well as the genres they will see from class partnerships. Through this WID component, the directors and consultants in our center have unique insight into students' learning in both the writing consultation and the classroom.

Across these two concurrent contexts of the classroom and writing center, several opportunities for transformation arise:

- Consultants might discuss genres or processes in new ways, providing students with new understandings or dissonance they must reconcile.

- Consultants help students adapt ideas, concepts, and processes from their general forms in the classroom to the students' particular projects.

- Consultants are less likely than instructors to discuss ideas through the lens of a particular class or discipline, so consultants are better situated to help students connect their ideas to contexts beyond the classroom.

While these are small moments that we might not typically associate with transfer, they demonstrate the ubiquity of transformation in writing centers and provide a starting point for better understanding transfer. While my examples come from a disciplinary perspective, I believe many of these situations will be familiar to those in the broader writing center community and, too, will generate discussion and encourage others to identify similar moments of transformation in their own centers. By identifying and analyzing these moments, writing center staff can work to build more localized support systems for facilitating transfer.

1. Consultants might discuss genres or processes in new ways, providing students with new understandings or dissonance they must reconcile.

|

| Figure 2. An HWI consultant and student work together within the writing center space. Photo by Heidi McKee. |

This first example demonstrates the small transformations of language and understanding that can occur when students discuss classroom ideas with consultants. My center holds partnerships with several introductory Marketing courses. Not only do the director and assistant directors help the classroom instructors integrate writing assignments into the classroom, but we discuss the purpose and genre conventions of those assignments with the undergraduate consultants, and we each hold several consultations with undergraduate writers. The major assignment in most of these Marketing courses is an approximately 10-page, team-written market analysis report. As our consultants attest, one of the more common questions asked in these consultations is how to distinguish between the required and closely related "Market Segmentation" and "Target Market" sections of the report.

|

| Figure 3. An HWI consultant works with a team of writers on a collaborative report. Photo by Heidi McKee. |

In one example from my own consulting, a team had assigned each member a section of the report to write. When they brought the draft to the consultation, they realized that the Market Segmentation and Target Market sections of the report contained overlapping information, and they were struggling to determine which information should go where. While our consultants do have specialized genre knowledge, we always begin by helping writers identify and untangle what they already know about the genre, as well as where they can find more information–whether from a textbook, an online source, or the instructor. I began by asking the team what they understood as the purpose of each of these sections. As a team, they established that the Market Segmentation section involves segmenting a market according to demographics and interests, while the Target Market section involves further identifying features of and marketing strategies for a particular segment. From this conversation, I suggested that–rather than writing each section separately and concurrently–the group first needed to determine the market segments and then needed to conduct further research and develop marketing strategies for what they determine to be the "target" segment. In other words, I suggested that the Target Market section should build from the Market Segmentation. One student in the group resisted this idea. It seemed their instructor had heavily emphasized that the two sections were distinct. While I believe the instructor was communicating that the two sections had distinct purposes, the student believed that each section should communicate entirely unique information. My suggestion, then, provided a solution to the team's dilemma, but it was also at odds with what this student thought their instructor wanted.

Such dissonance, however, can be the impetus students need to investigate further and to develop a deeper understanding of an idea. These moments, when students realize their prior understanding is insufficient, are examples of what Yancey, Robertson, and Taczak call "critical incidents" (120). Critical incidents are moments when "efforts either do not succeed at all or succeed only minimally," and a student must "let go of or relax prior knowledge as they rethink what they have learned, revise their model and/or conception of writing, and write anew" (120). In this example, the student who believed those sections needed to be strictly separate eventually had to relax that prior understanding and see that, despite having a separate purpose, the focus of the sections were similar. I, too, faced a critical incident as my understanding was challenged, and I had to further investigate the genre with the students.

This student was also demonstrating attributes of a boundary guarder (Reiff and Bawarshi); they had a preconceived idea of how the genre should work, and they guarded that preconception even when it did not make sense for the information they were trying to communicate. I see this kind of boundary guarding often when a consultant makes a suggestion that a student writer resists on the grounds that the suggestion conflicts with the expectations of their instructor or the genre. In these situations, both the student writer and the consultant must "relax prior knowledge" and seek new information to resolve the conflict.

We can easily overlook these moments as a form of transfer. Knowledge and understanding are not neatly applied from one context to the next, but they are transformed and sometimes challenged. We might even view these moments negatively because they often involve some form of "failure" or struggle as students (and consultants) realize their prior knowledge is insufficient. Further, we often do not see the moment when students make necessary adjustments to their ways of knowing. In my own example, the students decided to discuss their approach to the Market Segmentation and Target Market sections of the report with their instructor. I was not present for that moment of clarification, but our writing center conversation was the key to encouraging the students to seek new information. As Yancey, Robertson, and Taczak theorize, these moments of critical incident are necessary for learners to "relax prior knowledge" and develop deeper understandings in order to transfer.

2. Consultants help students adapt ideas, concepts, and processes from their general forms in the classroom to the students' particular projects.

Another form of transformation in centers involves transforming classroom concepts to fit particular assignments and, in the process, facilitating transformational learning, or preparing students to engage in similar activities in the future (Smart and Brown; Bawarshi). In addition to the Marketing partnership, our center also holds partnerships with several sections of both Intermediate Microeconomic Theory and Intermediate Macroeconomic Theory courses. The Microeconomic Theory courses ask students to apply a microeconomic theory they have learned in the course to a topic or real-world scenario that interests them, while the Macroeconomic Theory courses ask students to use macro theories to describe the effects of the 2008 Recession on a non-U.S. country.

Many of these students understand the stand-alone theories discussed in the classroom but few have yet grasped the nuance the theories take on when applied to a real situation. This assignment, in which students take a theory learned in the classroom and practice adapting it to the scenarios in their papers, asks students to practice what transfer theorists David N. Perkins and Gavriel Salomon call abstraction. That is, something is learned in one context; it is abstracted; and it can then be adapted to a future context. They explain, "A chess player might contemplate basic principles of chess strategy, such as control of the center, and reflectively ask what such principles might mean in other contexts" (26). In this example, the chess player abstracts a general principle (control of the center) from a specific context in order to apply it to others. Similarly, learning a theory in a classroom is like being provided an already abstracted form of knowledge; it is a general principle that students must then adapt to fit specific contexts.

Because abstracted ideas must be adapted to particular situations, this, too, is a form of transfer as transformation. In one session I observed with a consultant-in-training, a student writer was outlining a paper about two gaming consoles as substitute goods (i.e., two or more products that fill the same consumer needs). However, through the process of outlining the paper and applying this theory to the scenario, they began to rethink the consoles as "close substitutes" rather than as "perfect substitutes." In other words, as they worked through the particulars of the scenario, they were forced to transform their understanding of how the theory applied. As theories such as DePalma and Ringer's adaptive transfer suggest, transfer accounts for "both the reuse and the reshaping of prior writing knowledge to fit new contexts" (135; emphasis added). This student's adaptation of the theory to their particular scenario represents a form of transfer.

This assignment also serves as an example of transfer as knowing with (Broudy; Bawarshi). A major purpose of the assignment is to provide students practice applying economic theory to complex situations so they can do so more readily in the future. In other words, these papers or the process of writing them will not necessarily be something students apply directly to another context; however, with this experience, instructors hope students are better prepared to perform similar tasks in the future. Once again, while we do not always see this moment of knowing with during the consultation itself, Broudy's and Bawarshi's theories suggest we are playing an important role in transfer by supporting students in this practice.

3. Consultants are less likely than instructors to discuss ideas through the lens of a particular class or discipline, so consultants are better situated to help students connect their ideas to contexts beyond the classroom.

|

| Figure 4. A business student practices a class presentation with an HWI consultant. Photo by Heidi McKee. |

Transformation also involves integrating learning from both prior and new contexts so that "[both] may be understood differently" (Nowacek 25). This form of transformation can also be seen in the Intermediate Microeconomic Theory papers described previously. These papers take the form of a 500-700 word editorial, similar to what one might read in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, or Economist. As students pick situations to write about, many instructors encourage them to choose engaging topics—something that the students enjoy researching and writing about, as well as something that a generalist audience would be interested in reading. In other words, they encourage students to choose topics beyond what might be immediately identifiable as an economic issue in order to demonstrate the prevalence of economics.

Encouraging students to connect their learning in the classroom to topics and interests outside the classroom can be transformational both to the students' learning and to the assignment at hand. Fortunately, the process of helping students choose an engaging topic is familiar to most consultants. I previously referenced a consultation in which the student discussed gaming consoles as substitute goods. At the beginning of that consultation, the student was struggling to choose a topic. When the consultant asked the student what their interests were, the student, somewhat skeptically, listed a few hobbies, one of which was video games. The consultant then asked which games and consoles the student liked, and the idea developed out of that conversation. Muriel Harris notes, "Students can also offer other useful information they would be less willing to give teachers. Sitting with a student for a half-hour or an hour, a tutor is able to work primarily with the writer as a person, even when the paper is there on the table between them" (29). In their role, consultants are uniquely positioned to listen to students and help them draw from experiences that an instructor is less likely to have access to.

|

| Figure 5. An HWI consultant and student work together in the writing center. Photo by Heidi McKee. |

Additionally, as Julie Hagemann points out, consultants often have insights into what students are doing in multiple courses, so they can help them draw connections between seemingly disparate topics and assignments. One student I worked with brought in a sales pitch they were preparing for an Entrepreneurship class. The student was excited about this project and had plans to continue work on it outside of the class. When the student later brought in their Microeconomics assignment with only vague ideas of how to approach it, I was able to ask how an economic lens informed the Entrepreneurship project. Not only did this focus help the student adapt and apply economic theory, but it helped them to understand their product and pitch from a new perspective.

Blending knowledge from multiple contexts is yet another overlooked form of transfer. As Nowacek emphasizes, transfer is "an act of reconstruction" in which "both the old and new contexts . . . may be understood differently" (25). This, too, is an example of remix (Yancey, Robertson, and Taczak). The students in the previous examples were not just "grafting isolated bits of new knowledge onto . . . prior knowledge" (112) but meaningfully integrating the two. Transfer, then, does not necessarily require a clean transition from one physical context to another. Rather, much of the transfer that writing consultants see involves remixing seemingly disparate ideas.

Strategies for Identifying Transformation in Consultations

For writing center practitioners to become more intentional in how we facilitate transfer, I believe the first step is to identify unique moments of and opportunities for transformation in our own centers, as I have done above. If we look only for clear-cut moments of knowledge application, we will miss smaller moments of change that occur in our writing centers every day and which we can leverage to better facilitate transfer. By identifying these moments, consultants can reflect on and develop more nuanced understandings of their role and influence. I present the following questions as starting points for such reflection but hope this leads to more robust discussions among writing center staffs:

- What types of transformation (e.g., of genres, language, understandings, dispositions, and processes) can you identify from your experiences working in the center? In other words, when a student leaves the center, in what ways are they, their ideas, or their work transformed? How might that transformation prepare them for future writing?

- What was your role in those transformative moments? How can you encourage or facilitate transformation without being overly directive?

- What assignments do you commonly see in your center, and how do those particular assignments facilitate transformation?

- In what ways does your center's policies, training, or mission statement implicitly address transformation?

A transfer lens can also lead to new approaches in consulting. In our consultant preparation course, the HWI consultants and I talked about how discussions of prior knowledge and future contexts can generatively guide a writing consultation. When student writers bring in an assignment, consultants can ask what the students have done that is similar to or different from their current assignment. Consultants can also ask students how their current assignment informs work they will do in the future, and how that future work might be similar or different. By encouraging students to draw these connections across their work contexts, and especially to think about how their knowledge and practices must be adapted or transformed, consultants can develop a better understanding of the student writers' needs and can help to facilitate transfer both in the current assignment and in future work.

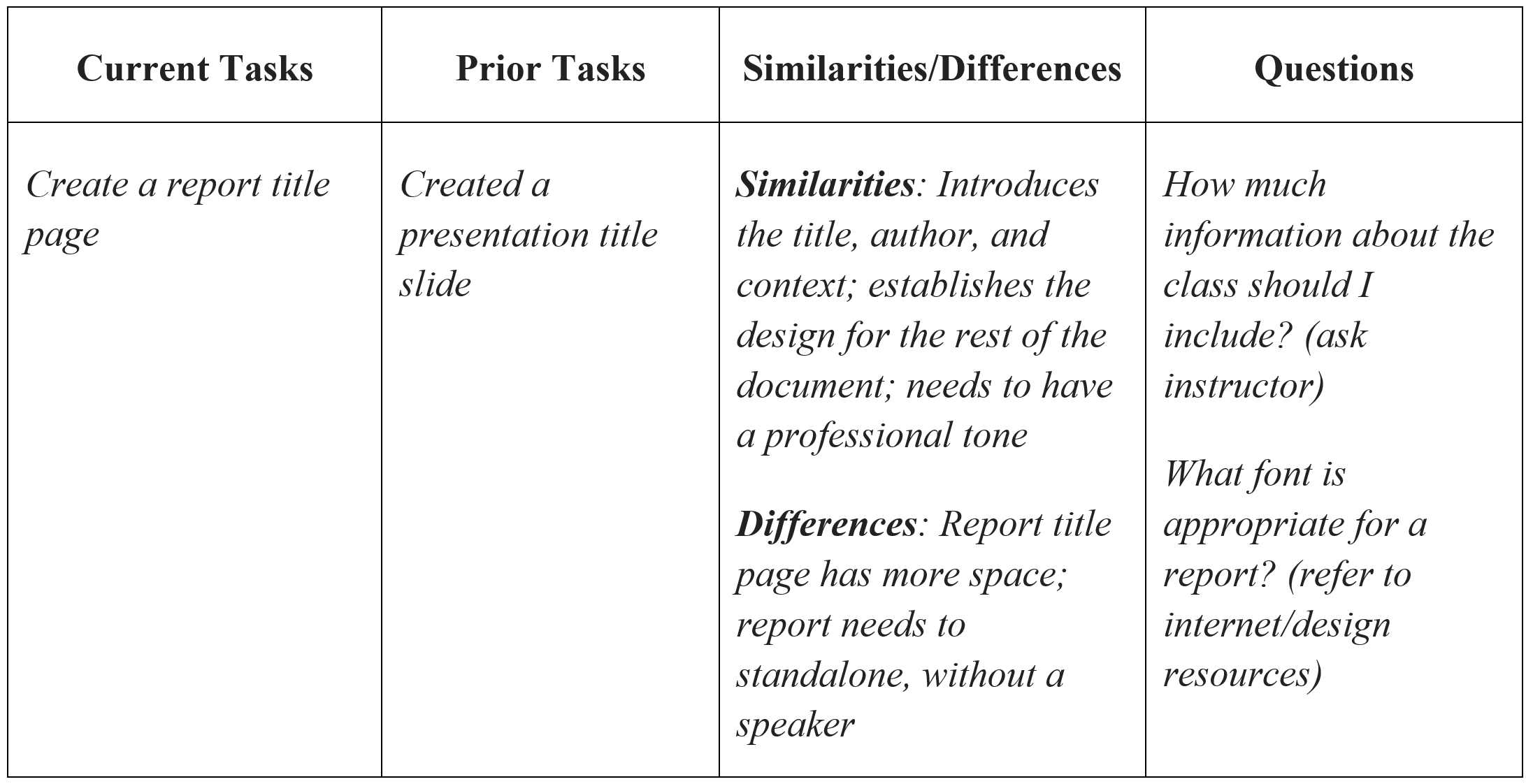

To familiarize consultants with the concept of transfer and the transformation that occurs between contexts, I created the following activity1 that asks them to break down one of their own assignments into smaller tasks, to list prior activities that relate to or inform the present tasks, and to think through the ways their approaches must adapt between the two contexts. If there's time, consultants can also look ahead to related future tasks and reflect on how their knowledge, genre, or approaches might need to be further adapted.

Identifying Similarities and Differences across Writing Tasks

Think about one of your current or upcoming assignments, and break it into smaller, individual tasks. For example, writing a report might involve (1) creating a title page, (2) compiling a table of contents, (3) writing an executive summary, (4) researching your topic, (5) drafting individual sections, (6) adding tables and figures, etc. List these tasks in the "Current Tasks" column of the table below.

Next, in the "Prior Tasks" column, describe prior work you've done or encountered that is similar to each current task. For example, perhaps you designed a title page for a previous assignment. Or maybe you haven't designed a title page for a report, but you created a title slide for a presentation. List one or two of these related experiences.

Then, in the "Similarities/Differences" column, describe any key similarities or differences between your earlier experience and your current task. In other words, what might you be able to approach in the same way, and what might you need to adapt?

Finally, in the right-hand column, list any questions you still need answered before you can complete the current task. If possible, also note where you can find that information, such as from an instructor, a textbook, or an internet resource.

Table 2

Similarities and Differences across Writing Tasks

While consultants had grasped the idea of transfer as adaptation and transformation on a theoretical level, they said this activity helped them to see how adaptation is a subconscious process they go through every time they approach a new assignment and that meta-awareness could ease that process. They also suggested there could be value in using this assignment with a student writer struggling to find their way into a new assignment or genre. I believe such explicit discussions about prior knowledge and future contexts can further enhance the transformative work centers already do.

As Devet describes, transfer is already central to what we do in the writing center: "Boundaries are crossed. New ideas are shaped. Transfer occurs" (138). Even Stephen North's well-known mantra, "to produce better writers, not better writing," signals a moment of transformation. Every day consultants support writers in adapting their genres, ideas, and processes in ways that have lasting and meaningful effects, yet if we consider transfer only as the direct application of prior knowledge, we are going to overlook a lot of this important work we are already doing. Transfer is a highly complex process, and recognizing and leveraging the transformative moments that foster transfer is one way that practitioners can develop more nuanced understandings of the lasting effects of our work.

As Devet describes, transfer is already central to what we do in the writing center: "Boundaries are crossed. New ideas are shaped. Transfer occurs" (138). Even Stephen North's well-known mantra, "to produce better writers, not better writing," signals a moment of transformation. Every day consultants support writers in adapting their genres, ideas, and processes in ways that have lasting and meaningful effects, yet if we consider transfer only as the direct application of prior knowledge, we are going to overlook a lot of this important work we are already doing. Transfer is a highly complex process, and recognizing and leveraging the transformative moments that foster transfer is one way that practitioners can develop more nuanced understandings of the lasting effects of our work.

NOTE

1 (back to text)

For additional training exercises for transfer, see Candace Hastings' "Playing Around: Tutoring for Transfer in the Writing Center" and Heather Hill's "Strategies for Creating a Transfer-Focused Tutor Education Program."

Works Cited

Bawarshi, Anis. "Economies of Knowledge Transfer and the Use-Value of First-Year Composition." Economies of Writing: Revaluations in Rhetoric and Composition, edited by Bruce Horner, Brice Nordquist, and Susan M. Ryan, Utah State UP, 2017, pp. 87-98.

Beach, King. "Consequential Transitions: A Sociocultural Expedition Beyond Transfer in Education." Review of Research in Education, vol. 24, no. 1, 1999, pp. 101-39.

Broudy, Harry S. "Types of Knowledge and Purposes of Education." Schooling and the Acquisition of Knowledge, edited by Richard Chase Anderson, Rand J. Spiro, and William Edward Montague, Erlbaum, 1977, pp. 1-17.

DePalma, Michael-John, and Jeffrey M. Ringer. "Toward a Theory of Adaptive Transfer: Expanding Disciplinary Discussions of 'Transfer' in Second-Language Writing and Composition Studies." Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 20, no. 2, 2011, pp. 134-47.

Devet, Bonnie. "The Writing Center and Transfer of Learning: A Primer for Directors." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 1, 2015, pp. 119-51.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn. "Building Connections and Transferring Knowledge: The Benefits of a Peer Tutoring Course Beyond the Writing Center." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 1, 2015, pp. 153-81.

Hagemann, Julie. "Writing Centers as Sites for Writing Transfer Research." Writing Center Perspectives, edited by Byron L. Stay, Christina Murphy, and Eric Hobson, NWCA Press, 1995, pp. 120-31.

Harris, Muriel. "Talking in the Middle: Why Writers Need Writing Tutors." College English, vol. 57, no. 1, 1995, pp. 27-42.

North, Stephen M. "The Idea of a Writing Center." College English, vol. 46, no. 5, 1984, pp. 433-46.

Nowacek, Rebecca S. Agents of Integration: Understanding Transfer as a Rhetorical Act. Southern Illinois UP, 2011.

Perkins, David N., and Gavriel Salomon. "Teaching for Transfer." Educational Leadership, vol. 46, no. 1, 1998, pp. 22-32.

Reiff, Mary Jo, and Anis Bawarshi. "Tracing Discursive Resources: How Students Use Prior Genre Knowledge to Negotiate New Writing Contexts in First-Year Composition." Written Communication, vol. 28, no. 3, 2011, pp. 312-37.

Smart, Graham, and Nicole Brown. "Learning Transfer or Transforming Learning?: Student Interns Reinventing Expert Writing Practices in the Workplace." Technostyle, vol. 18, no. 1, 2002, pp. 117-41.

Wardle, Elizabeth. "Understanding 'Transfer' from FYC: Preliminary Results of a Longitudinal Study." Writing Program Administration, vol. 31, no. 2, 2007, pp. 65-85.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, et al. Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. Utah State UP, 2014.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Heidi McKee, the Director of the Howe Writing Initiative; to the founders, Roger and Joyce Howe, for their generous contributions; and to the assistant directors, the consultants, and the many writers I worked with and learned from over the years.

BIO

Cynthia Johnson worked for two years as an Assistant Director of the Howe Writing Initiative, the Writing Center and WID Program for the Farmer School of Business at Miami University. She is now an Assistant Professor at the University of Central Oklahoma. Her research examines social, material, and rhetorical influences on transfer.