“We Want to Be Intersectional”: Asian American College Students’ Extracurricular Rhetorical Education

“We Want to Be Intersectional”: Asian American College Students’ Extracurricular Rhetorical Education

Peitho Volume 23 Issue 4, Summer 2021

Author(s): Allison Dziuba

Allison Dziuba is a PhD candidate in English at the University of California, Irvine. Her research interests include feminist rhetorics, emotion studies, and extracurricular student writing. She is a recipient of the American Association of University Women (AAUW) American Dissertation Fellowship.

Abstract: In this article, I explore how three Asian American student groups work to create spaces of intellectual and social belonging through their longing “to be intersectional.” I argue that their efforts are forms of extracurricular rhetorical education: each group employs “intersectionality” to understand their positions as speaking and writing subjects who are always already embedded within systems of power. “Intersectionality” serves as an epistemological and discursive method that is core to how these students relate to one another and to their experiences in university settings.

Tags: Asian American, extracurricular, IntersectionalityAt a recent meeting of UC Irvine’s South Asia and Diaspora Student Association (SADSA),1 two members presented their research on the demographic characteristics of the eight South Asian countries along with details about the living conditions of queer, Indigenous, and undocumented populations there. As one presenter noted, they called attention to how these different positionalities interact with nationality because they “want[ed] to be intersectional.” Joining the meeting as a graduate student researcher, I noted this interesting use of “intersectional.” I have applied this descriptor to a specific intellectual legacy: rooted in Black women’s theorizing and activism, an intersectional feminist approach asserts that categories of oppression, such as race and gender, are imbricated and thereby create particular material conditions.2 “Intersectionality” was famously coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. The term has since traveled beyond feminist and legal criticism and has, at times, been applied as a clumsy alternative to BIPOC or minoritized—as in, recruiting “intersectional people” to meet institutional diversity goals. However, the SADSA members’ use implied an orientation to experience and knowledge aligned with the term’s Black feminist origins. I interpreted “being intersectional,” then, to mean approaching the world with the foundational assertion that elements of a person’s positionality (e.g., South Asian, college student, woman, biological sciences major, able-bodied) co-constitute that person’s relationships to systems of power. SADSA’s collective exploration of South Asian nations, therefore, recognized the heterogeneous experiences of “nationality” as inflected by histories of migration, colonization, and marginalization.

In this article, I explore how three Asian American3 student groups, including SADSA, work to create spaces of intellectual and social belonging through their longing “to be intersectional.” I argue that these student groups’ efforts are forms of extracurricular rhetorical education: each group employs “intersectionality” (although only SADSA names it as such) to understand their positions as speaking and writing subjects who are always already embedded within systems of power. “Intersectionality” serves as an epistemological and discursive method that is core to how these students relate to one another and to their experiences in university settings. Not all the students and groups I spent time with connected their extracurricular efforts to intersectional feminist analysis and its foundations in Black feminism. My interest in their use of “intersectionality,” then, resides in their desire to collectively produce knowledge that is informed by their lived experiences as raced, gendered subjects.

The construction “be intersectional” resembles the imperative of Aimee Carrillo Rowe’s “be longing”: “two words, placed beside each other, not run together, phrases a command. The command is to ‘be’ ‘longing,’ not to be still, or be quiet, but to be longing” (16). Carrillo Rowe calls this a “resistive hailing,” turning Louis Althusser’s formulation on its head. She continues, “So the command of this ‘reverse interpellation’ is to call attention to the politics at stake in our belonging, and to envision an alternative” (16). For instance, SADSA members long to belong to one another. They recognize not only that their coalition of South Asian students claim different countries of origin but also that blanket characterizations of these origins can mask uneven distributions of power—hence, a longing to “be intersectional.” In enacting resistive hailings, the three student groups discussed here instantiate their belonging to each other, the campus, and the U.S. nation-state through collective rhetorical practices. By identifying these students’ activities as self-sponsored rhetorical education, I aim to extend scholarship that considers how and where people learn strategies for civic-engaged writing and speaking, especially among those who have been historically marginalized in traditional sites of education. For example, in their article on the UCI Muslim Student Union’s activism, Jonathan Alexander and Susan Jarratt trace these students’ rhetorical genealogies and examine the various influences—mostly non-curricular—on their perspectives and tactics. In my research, I have found that students’ rhetorical educations are formed dialogically between the curricular and extracurricular.

Also significant in this analysis is the concept of counterpublics: student group gatherings and communications become spaces to critique totalizing narratives of Asians in America and to generate alternative knowledges about Asian American history and current conditions, within the university environment and beyond. Nancy Fraser includes material conditions and physical spaces alongside the circulation of written discourse in her conception of subaltern counterpublics; she counts bookstores, research centers, and conventions as part of a U.S. feminist subaltern counterpublic (67). Because my study centers the immediacy of embodied experience in student groups’ extracurricular activities and knowledge production, I am also building upon work that has linked student performance and writing. Jenn Fishman et al. show that through activities from “spoken-word events and slam poetry competitions to live radio broadcasts, public speaking, and theatrical presentations . . . [students’] embodying writing through voice, gesture, and movement can help early college students learn vital lessons about literacy” (226). My research participants’ mutual education practices represent learning that influences their formal college educations but also extends into their social and professional lives. Through these club gatherings—embodied assemblages of learners, teachers, and collaborators—students reflect critically on their positionalities as twenty-first century Asian American college students.

The findings presented in this article are selected from a larger, IRB-approved ethnography that I conducted during academic years 2018–19 and 2019–20. My study asked how and whether extracurricular student groups serve as sites for literacy learning. Foregrounding this research is my own positionality: I identify as Asian American, specifically hapa or mixed-race Asian; my undergraduate extracurricular activities, in groups like the Hapa Club, were significantly in dialogue with my curricular learning. I contacted UCI student groups who focus on aspects of Asian America and racial, cultural, and national affiliations. After receiving permission to attend meetings, I functionally joined several groups, introducing myself to club members as both a graduate researcher and a fellow club participant. I attended (and in SADSA’s case helped staff) special events, such as culture nights. I further followed up with individual club members, often leaders, for one-on-one interviews to discuss their reasons for club involvement (see Appendix for my basic interview questions).

My research process and my discussion here employ a feminist rhetorical framework. Per Jacqueline Jones Royster and Gesa E. Kirsch, the personal and professional come together in how we narrate our research: my extracurricular experiences initially led to my inquiry into Asian American clubs. As such, my scholarly participant observations are inextricable from my affinity with these groups of students. Building on Beverly Moss’s insights about ethnographies of communication, and specifically about studying communities of which the ethnographer is a part, I have endeavored to mark how my personal investments influence my findings but also to look with an analytical eye—to both make the strange familiar and the familiar, strange. I believe that ethical scholarship of this sort means that I should not be the only one to benefit (along these lines, see Eileen Schell on what makes feminist rhetorical studies feminist). I financially supported the clubs I spent time with by paying membership fees or buying tickets to their events, and I offered to share my academic experiences with those club members who expressed interest in graduate study. In my analysis, I am committed to centering voices and spaces that contest white heteropatriarchy. Even though I include individual interviewees, my focus is on the student groups’ collective work, and thereby I aim to reflexively challenge any singular narrative.

Feminist scholarship teaches us that feminist theory is inextricably bound to feminist activism—the two are dyadic, shaping and reshaping one another. We cannot talk about feminist thought absent feminist practice—in fact, lived experiences are crucially part of the theorizing process. My ethnographic research provides evidence of this, as student groups strive “to be intersectional” and, in the process, refigure identity formations. My study participants show that rhetorical education is similar: it is necessary to understand whether and how the tools we, as teachers, share with our students operate in the spaces our students choose to occupy and create for themselves. This is not to say that university courses do not present real rhetorical contexts, but we must acknowledge, as Susan Wells writes, “that the writing classroom has no public exigency: the writing classroom does important cultural work for the million and a half students it serves each year, but it does not carry out that work through the texts it produces” (338). We must therefore attend to how students deploy and reshape their rhetorical learning when there is public exigency, for example, when their rhetorical positioning bears on how they interact with identity, community, history, and politics. The following discussion provides a brief sketch of the historical and political experiences of Asian Americans in Southern California; I then examine how the embodied gatherings of student clubs nurture mutual education practices; I conclude with the tensions between knowledges valued in extracurricular and in curricular spaces.

Belonging in/to Southern California

As of fall 2019, about 36 percent of the UCI student body identified as Asian (National Center for Education Statistics). UCI is recognized by the federal government as an Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander–Serving Institution. This sizeable and diverse segment of the student body is located within an Asian-majority city4 and a U.S. region that generations of Asian immigrants and their descendants have called home. According to the UCI library archives, Chinese laborers constituted the majority of Asian immigrants to California during the nineteenth century; farm workers found employment in Orange County. Notably, the year 1965 saw the founding of UCI as well as the national Immigration Act, which lifted quotas on non–western European countries and allowed family members abroad to join their sponsors in the U.S. The immigrant population diversified in the latter twentieth century: some 50,000 Vietnamese refugees arrived at Camp Pendleton in northern San Diego County after 1975, and, as a result of housing availability, the location of resettlement agencies, and job opportunities, among other factors, many Vietnamese immigrants ultimately made their homes in Westminster and Garden Grove (Berg). Today, the “Little Saigon” neighborhood is the largest Vietnamese enclave in the U.S.

Despite this regional history, Asian American students have struggled to find belonging within university spaces. In spring 1991, around 400 students representing various clubs affiliated with the Cross-Cultural Center protested Asian Heritage Week. An article in Rice Paper, the student newspaper geared toward the Asian/Pacific communities, recounts the disruption of scheduled cultural performances, noting that a Pilipinx-American club “withdrew their dances and music entirely because they felt that Asian Heritage Week has been used as the jewel on the crown by the administration which constantly claims diversity yet in substance are unwilling to support Asians with Asian American Studies.” The club president is quoted in the article, explaining his group’s decision: “We feel it would be hypocritical for us to perform. Our performance supposedly celebrates the diversity present on the campus. … we are seen as a token for this university and it is very difficult for us to go up on stage acting as if we are satisfied when in actuality we are not, due to the lack of Asian American studies in our current curriculum.” The push for Asian American studies continued for the next two years, culminating in two occupations of the university chancellor’s office in April and June 1993 and a hunger strike, and resulting in the administration’s hiring of three faculty members to teach courses in Asian American studies (Trinh).

Michelle Ko, writing in the same 1991 issue of Rice Paper, tracks the history of ethnic studies activism. She describes the movement’s beginnings at San Francisco State University in the 1960s and Asian American students’ pivotal role. She entreats readers to remember the past as they agitate for a fairer future. Ko, like the twenty-first-century students in my study, is confronted by the wide-reaching effects of the model minority myth, a stereotype of Asian passivity notably propagated by a 1966 U.S. News & World Report article (Lee). In the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, the myth was leveraged against interracial solidarity, pitting Asian Americans against African American, Latinx, and Indigenous populations, who supposedly were not making good on the so-called American Dream. While popular representations of Asians as smart, law abiding, and economically successful appear complimentary, they mask anxieties about foreign contamination of white America. The model minority myth can be understood as a colonial containment strategy: U.S. imperialism can claim Asians simultaneously as valuable members of society and as perpetual outsiders who are racially and culturally Other. Ko’s article, then, performs a resistive hailing: she asserts Asian American-ness that includes political activism and coalitional work with other racially marginalized groups.

Scholarship on Asian American rhetorics provides an important point of orientation for situating the experiences of Asian American rhetors at UCI, past and present. LuMing Mao and Morris Young characterize Asian American rhetoric as a rhetoric of becoming: it is performative, generative, transformative, and heterogeneous. Despite their use of the singular “rhetoric,” they insist on Asian American rhetoric’s inherent dynamism:

While we very much want to claim that Asian American rhetoric commands a sense of unity or collective identity for its users, we want to note that such rhetoric cannot help but embody internal differences, ambivalences, and even contradictions as each and every specific communicative situation—where Asian American rhetoric is invoked, deployed, or developed—is informed and inflected by diverse contexts, by different relations of asymmetry, and by, most simply put, heterogeneous voices. (5)

Writing ten years later, Terese Guinsatao Monberg and Young further define the potential of studying Asian American rhetoric: “this work has had to account for histories of immigration; the comparative, cultural, and national contexts for rhetoric; or the development of innovative rhetorical practices in response to constructions of otherness.” The Asian American rhetorical practices I discuss here exist at the intersection of embodied, racialized experience; cultural upbringing; and performative—and thereby dynamic—assertions of self. In her study of Vietnamese American undergraduates, Haivan Hoang builds on Judith Butler’s notion of performative identity, arguing that the students in her ethnography reconfigure “Americanness” through their performances. Indeed, the Asian American students in my study—through their use of multilingual repertoires and self-sponsored education in Asian history, for instance—assert that these are all distinctly American activities. That said, to make the blanket assertion that these students, with their UCI-branded sweatshirts and weekend trips to Disneyland, are “as American as anyone else” would be to render invisible the layered tensions of national belonging and racial/ethnic identification stemming from different histories of Asian immigration to California. The UCI student population includes many from mainland China. International students who arrive on campus days before classes begin will likely feel that they are “Asian” and “American” in proportions different from their peers whose predecessors made the west coast their home in the nineteenth century, and again different from those whose families emigrated from outposts of American imperialism in the mid-to-late twentieth century. As Guinsatao Monberg and Young assert, Asian American “rhetorical actors negotiate across and within different positions rather than in opposition to one location/identity or another, or from a hybrid third position.” These student groups’ belonging, then, is inherently transnational, in continual movement—much as their longing to “be intersectional” describes the ongoing navigation of differential power relations.

Longing to Be Intersectional

In bringing trans theory to bear in Asian American rhetoric, V. Jo Hsu describes a core principle of intersectional feminist analysis: “Individual stories have political significance … as acute, felt insight into the violence and oversights of our institutions. Although discussions so often compartmentalize elements of our identities, we don’t live single-issue lives.” The three UCI student groups’ activities offer rich examples of their members’ multidimentional lives, particularly vis-à-vis power structures. SADSA’s leadership explicitly states this orientation in their goals:

- We want to engage in the celebration of South Asian cultures, but also critiquing them as well

- Create an open brave and safe space/forum for critical discussions and engagement with other cultures

- Decolonization – challenge the commonalities and differences between the cultures of the region

- Create unity between South Asian organizations and students on campus

- Raise awareness around relevant political issues

- Provide affordable social events and no-cost membership to everyone.

(“First General Meeting”)

These objectives demonstrate the group’s intellectual and social justice commitments, providing opportunities for cultural sharing but with attention to the structural forces (for instance, colonialism) that can stymie solidarity. Student group members teach and challenge one another to belong differently to American society—to “be intersectional” in discussions of their own privileges and oppressions. As Mao and Young write, “For Asian Americans, as with others often placed on the margins of culture, language provides the possibility to realize the rhetorical construction of identity and write oneself literally into the pages of history and culture” (6). The leadership team noted SADSA’s strides toward enacting its vision, among them philanthropic projects and recognition from UCI for their charitable fundraising. “Being intersectional” further speaks to how these undergraduate students bring academic concepts to bear on their extracurricular activities and alludes to tensions these students see between their formal education and their lives beyond the classroom. SADSA frequently discusses the need to pluralize Asian American representation at UCI, where academic offerings on Asia often focus on East and Southeast areas. Zee, one of SADSA’s co-founders, reflected, “. . . a lot of the learning I experienced at UCI did not come from the classroom unfortunately. My club’s values and goals didn’t always align with what I was learning.” While SADSA publicly claims its commitments to intersectional feminist analysis, the other two groups I highlight here did not do so explicitly. However, I recognize significant feminist rhetorical moves in their efforts as employing some of the same structural critiques as SADSA’s outlined above.

The Pilipinx-American Club (PAC) has been a presence on campus since UCI’s early years, forged during the state-wide and national movements for ethnic studies. Initially part of the university’s umbrella Asian/Pacific student organization, PAC grew in membership and ambition and became an independent student group in the 1990s, the same era that saw student agitation for Asian American studies. Compared with Pilipinx-American student groups at other Southern California colleges, PAC “is old,” accruing political and social clout because of its influential alumni community (including a high-level UCI administrator). The club’s position within the region is conscientiously embedded within the transnational, diasporic community. For example, club members begin meetings by singing the Philippines national anthem in Tagalog. According to Matthew, an Asian American studies major and active participant in club governance, PAC aims to share Pilipinx history, particularly within the Southern California context: there are annual field trips to Filipinotown in LA, with stops including Unidad Park, the Pilipinx-American Veterans Memorial, and a Pilipinx-American church. This curated tour, typically organized by the club’s cultural chair, demonstrates the Pilipinx-American community’s “substantial, physical history” here in the region, a history that Matthew contends is often forgotten. Matthew, born and raised in the Philippines, explained that he wants to “pop the UCI bubble” in order to facilitate PAC’s engagement with the various histories of Pilipinx-Americans beyond academic institutionalization. Matthew shared a memorable adage: “k(no)w history, k(no)w self.”

Other members of PAC similarly touted the organization’s politically engaged aims, but their comments demonstrated how “intersectionality” continues to be aspirational for their club at large. Ligaya, a rank-and-file member, joined PAC hoping to raise awareness about the systematic erasure of Pilipinx-American history, both at UCI and in broader U.S. consciousness. In our email correspondence, she wrote, “Pilipinx involvement in the advancement of workers’ rights by organizers such as Larry Itliong alongside Cesar Chavez during the 1960’s strikes against grape growers remains largely untold.” She included the titles of articles documenting this forgotten figure of the labor movement, evidencing Ligaya’s self-sponsored investigation into Itliong’s legacy. She explained that October is Pilipinx-American History Month and that she hoped PAC would address issues of historical erasure in their programming.

Max, PAC’s community advocacy coordinator, is responsible for staying abreast of political issues and current events that are relevant to the Pilipinx-American community at UCI. She also coordinates volunteer opportunities, such as with national advocacy group Justice for Filipino-American Veterans. As a self-described military brat, Max lived in Guam, Virginia, Fresno, Sacramento, and Southern California, and encountering different regional contexts and populations helped her recognize her own privileges and informed her political intentions. Max has organized general meetings of PAC in which she has tried to challenge the larger membership to consider issues that she feels are not usually discussed. For example, one meeting featured an interactive group game to help members think about the layers of their identity and privilege. Max said that she wants to host another meeting to discuss the Asian model minority myth, particularly to address how Pilipinx-Americans can be both oppressed and oppressors of other minority groups. Max said she is committed to making PAC more political, adding that many Asian Americans are reluctant to participate in politics because they feel that their voices do not matter. She cited her own parents, whose focus on providing for the family and assimilating to American life often eclipsed direct political engagement. In her efforts to mobilize Pilipinx-Americans at UCI, Max held a voter information session before the 2018 midterm elections (she noted, unfortunately, that attendance was low).

For Matthew, Ligaya, and Max, bringing their outside knowledges to PAC constitutes their efforts to belong. Speaking and writing from distinct positionalities, they long to “be intersectional” in how they discursively define being Pilipinx-American. For instance, Max connected her experiences in student government and activism to her agenda for PAC. Discussing her involvement with a campus climate initiative, she said that she wants all her peers to feel safe, supported, and welcome. She has attended student leadership conferences and applied lessons learned, particularly from workshops that addressed anti-blackness in Asian American communities. She has also canvassed for Congresswoman Katie Porter. Max explained that her experiences have collectively informed how she tries to confront the model minority stereotype and the social divisions it causes.

The weekly meetings of both SADSA and PAC typically involve presentations or activities prepared by club leaders along with small group conversations. The Asian Americans for Christ (AAC), in contrast, structures gatherings around the more conventional pedagogical modes of textual study and lecture. At each fellowship meeting, AAC student coordinators greet the full group from the front of the lecture hall, using PowerPoint slides to support their verbal announcements. They also introduce the week’s guest pastor, who delivers remarks based on AAC’s theme for the academic year (the theme for 2018–19 was “being rooted”). I interviewed two of the coordinators, who explained that they generally prepare a short script to introduce guest speakers and read these notes verbatim from their smartphones. Coordinators are also responsible for summarizing the sermon and sharing these notes with the club membership. While AAC membership is open to all, from what I have observed guest pastors frequently self-identify as Asian American and speak to the particular experiences of Asian American college students.

Based on my time with AAC, I see theirs as a narrower desire to “be intersectional,” one that is built on certain assumptions of common racialized and gendered experience. Whereas SADSA and PAC seek feelings of belonging first through cultural and national affinity and then unpack how that affinity can mask heterogeneity, AAC finds belonging across particularities by asserting narrative universality. AAC members are encouraged to join small groups, which function as Biblical reading and peer support groups. Students may join small groups based on their year in school (first-years or upperclassmen/women) and gender. I interviewed one small group leader who remarked that meeting in gender-specific groups allowed her to feel more comfortable; she sees this as a more open and honest space to bond with her female peers over shared experiences and emotions. She went on to describe how she leads, with one other club member, the first-year women’s group. All small groups work through the same sections of the Bible or other book each quarter, but each small group’s leaders decide how to orient the discussion and draft questions that help to relate the reading to the small group’s experiences and to connect them with God. My interviewee elaborated on her process: she reads the passage multiple times, prays for understanding and insight, annotates the passage in a journal looking particularly at the verbs and nouns that are used, and develops questions based on this in-depth reading. She aims to facilitate others’ understanding of the text and active reading of the Bible. She tries to prompt the small group to consider what the passage might mean for their own lives. She shared a couple sample discussion questions: “What does it look like to rely on God for help in these situations [such as those described in the reading]? How do you know if you are relying on God and not just having really good self-control?” These gender- and class-level-exclusive groups seem to reify assumptions about sexuality (e.g., that being in an all-female group would eliminate possible romantic distractions) and academic status (e.g., that first-years are younger and coming out of high school)—so by extension, assumptions about how power affects these categories of identification. At the same time, these group spaces can provide relative safety, allowing participants to frankly unpack how being, say, an Asian American woman and graduating senior informs one’s hopes and fears about applying for jobs. In this way, small group participants long to be surrounded by “likeminded peers,” a phrase one member used to explain why he was drawn to AAC.

Connections between text and personal experience are highlighted during a quarterly event called Testimony Night, in which student speakers take the place of guest pastors. When I attended a Testimony Night, three students took turns addressing the full group; each selected a worship song to lead as an introduction to their story. The first two of three speakers referred to notes on their smartphones while speaking; one explained that she had written her statement out ahead of time and had shared it with the club coordinators, “just so they know what to expect.” The third speaker of the evening improvised more, aware of how her delivery would emotionally affect her listeners: “I wrote down my testimony, but I’m also going to speak from my heart. . . . I hope this will move you. . . . I don’t want you guys to lose hope.” All of the testimonies included metacognitive reflection on the composition of the speeches, usually involving “a lot of prayer.” They all recounted the speakers’ lives up until that point: upbringing, family arrangements, struggles faced, how they ultimately came to Christ and AAC and what they value in both.

These “I once was lost but now am found” stories demonstrated the students’ (perhaps implicit) understanding of the conversion narrative genre as well as highlighted their rhetorical awareness of their own and their audience’s positionalities as Asian American Christian college students and how one might be grappling with these overlapping spheres of belonging. For instance, one student said his adolescence in Taiwan was analogous to the idol-worshipping life in Athens referenced in Thessalonians. Students explicate how their racial, national, and religious affiliations interact with their positions within the university: all of the Testimony Night speakers talked about the need for Asian American Christians to support one another and to build lives of faith despite what they perceive as the vices of college life (e.g., alcohol, drugs, sex). This version of longing to “be intersectional,” then, explores how young, Christian Asian Americans face particular struggles but falls short of identifying how historical power asymmetries inform these struggles. The student speaker who aimed to move her listeners addressed gendered expectations within the context of her family life and the pressure to be an obedient daughter, but she did not relate her experiences to, say, the constraints of patriarchy or stereotypes of Asian women’s passivity. Her testimony might have cited the support of her all-female small group in her spiritual transformation; instead, she framed her story as one of self discovery. None of the speakers at the Testimony Night I attended directly connected their classroom learning to the task of addressing AAC peers. Other student group participants, most notably in SADSA and PAC, did share how their curricular and extracurricular educations inform one another.

Redefining the Extra/Curricular

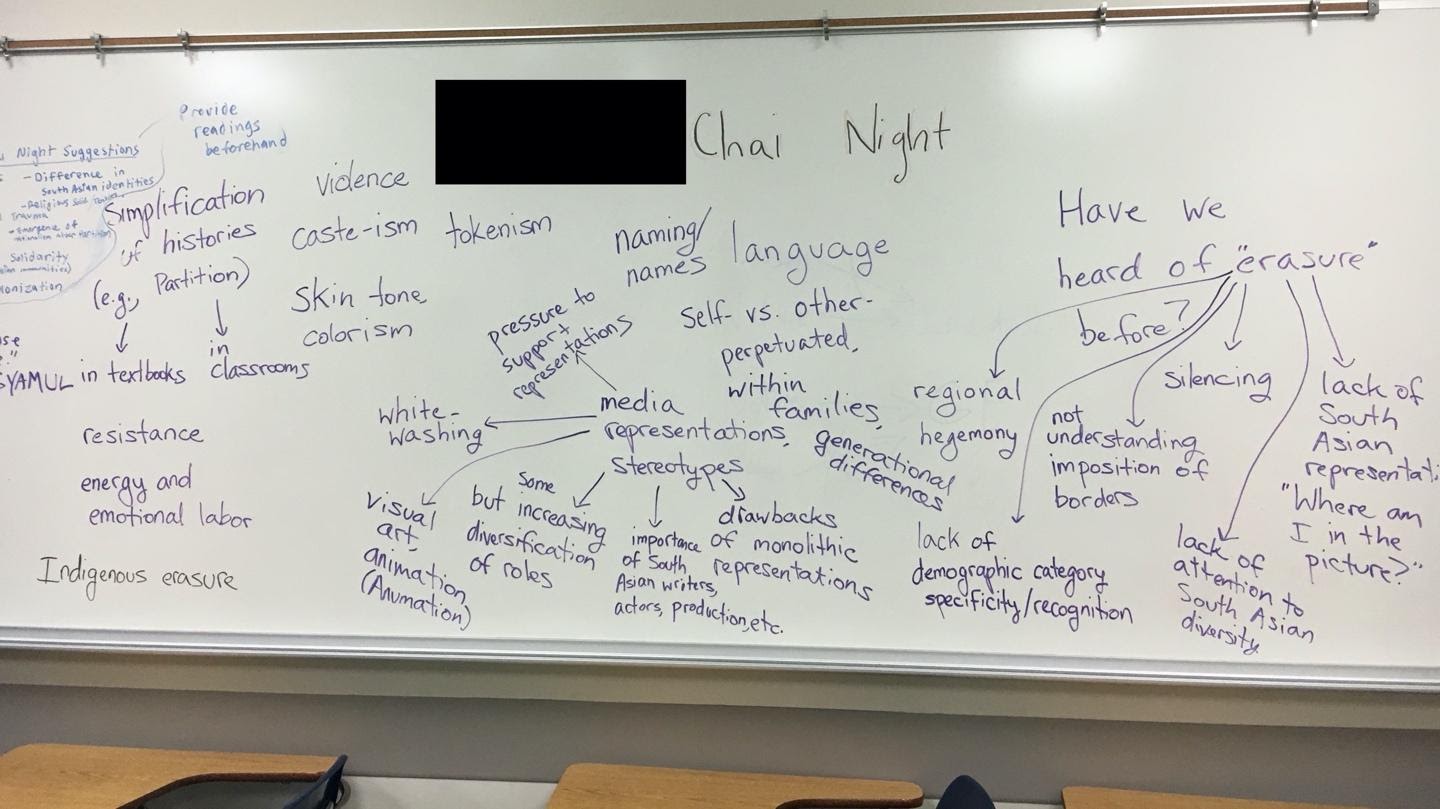

Several times each quarter, SADSA hosts discussion spaces called Chai Nights: students gather in a small classroom, circle up the desks, and enjoy chai and snacks provided by the club leaders. Each Chai Night prompts attendees to discuss a different aspect of South Asian identity and experience. The club has considered mental health among South Asian populations in the U.S., dating and relationships, and distinctions between cultural appropriation and appreciation. I volunteered to help take notes on the white board during the erasure discussion (see Figure 1). “Erasure” has been variously used to describe whitewashing in Hollywood or the elision of Asian American experiences through reliance on racial stereotypes. SADSA explored their own particular iteration of this idea in fall 2018. Topics ranged from the visibility of South Asian characters in popular media to the use of heritage languages and the proper pronunciation of students’ names.

Figure 1: Notes from SADSA’s Chai Night discussion of erasure.

Figure 1: Notes from SADSA’s Chai Night discussion of erasure.

The group of around 10 students considered critically how India-centric depictions of South Asian identity can erase ethnic and historical differences. As this coalition of students identifies their roots in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, they regularly reflect upon the issue of regional hegemony. At its founding, the club faced some pushback from South Asian nation–specific student clubs, who felt the coalition would siphon off campus resources and student membership. This particular dimension of erasure, which describes the uneven distribution of power within affinity groups, further informs this organization’s sense of where they fit in the university ecology. Their mission statement recognizes the club’s commitment to intersectional analysis: “We want to work with other communities to combat issues, such as LGBTQ+ rights, anti-blackness, media representation, color politics, and the list goes on.”

In the weeks following my attendance at this Chai Night, I interviewed Sithunada, a graduate student who helped found SADSA while he was an undergraduate. He explained that the club endeavors to create a space to discuss academic topics, like South Asian erasure, but in an approachable way—hence the creation of Chai Nights. Club leaders aim to create a welcoming environment where students can learn, informally but meaningfully, from one another. Sithunada added that the club draws upon curricular resources and cultivates university partnerships. For example, a previous Chai Night focused on colorism and anti-blackness and was co-facilitated by a professor in African American Studies; in fall 2018, the club was listed as one of the official sponsors of a campus dance festival, which featured guest performers. The blending of co- and extracurricular efforts highlights how these students perform academic literacies: the club’s examination of erasure demonstrates how cultural studies–style analyses inform their self-sponsoring learning. What’s more, these analytical skills are employed to critique institutional learning, as club members explained how many of their college courses have provided only passing reference to South Asian and diasporic histories.

Another of SADSA’s founders whom I quoted earlier, Zee, explained that the club’s work is fundamentally collaborative, citing knowledge and communication as the club’s driving forces and the importance of participants’ shared wisdom. Zee further explained that SADSA looks for opportunities to support campus, local, and international organizations, as shown in SADSA’s fundraising mentioned earlier. Through my own participation in group meetings and activities, I have seen SADSA amplify other South Asian student organizations by advertising and showing up for their events. SADSA members have also coordinated with student groups whose missions align with SADSA’s intersectional analytical stance, including student advocates for labor rights and students against apartheid in Palestine.

SADSA serves to fill a gap in many of its members’ formal educations by addressing the erasure of South Asian–specific histories and concerns. Simultaneously, as demonstrated through my interviews with club leaders and my observations of how club discussions are facilitated like humanities seminars, curricular learning crucially informs SADSA’s activities. This push and pull with the university often shows up in club members’ offhanded comments. While SADSA phased out membership dues in fall 2019, club members were expected to pay quarterly fees to help keep the organization running during the 2018–19 academic year. Explaining the need for funding, a club leader said, “When you start a club, they charge you!” (with “they” referring to university administration).

SADSA, PAC, and many other affinity groups organize culture nights as a way of making visible their learning to the broader campus and local communities. Occurring in the spring quarter, these events typically showcase student-written and -directed skits along with original dance and musical numbers. Hoang explains how these events have more rhetorical significance than immediately meets the eye: “What Culture Nights demonstrate is that performance is potentially performative in terms of constituting (not expressing) ethnic identity and cultural memories” (144; original emphasis). She specifically comments on the Vietnamese Students Association, a college student group with which Hoang spends significant time:

Even if the Culture Night audience’s response is largely unknown, what makes the student production performative is that it constructs what culture is on this Culture Night. Vietnamese and Vietnamese American culture, in this performance, is based on intergenerational, familial relationships and experiences. VSA’s stated purpose in producing Culture Night clarifies the performance’s performative purpose: to reconstruct cultural memory and thereby foster solidarity. (146; original emphasis)

Planning and executing a culture night involves substantial logistical efforts (e.g., reserving a space on campus, fundraising, advertising) and creative energies. I interviewed the PAC coordinators, who shared with me that the annual event traditionally features several dance suites that span regions, ethnic groups, and histories of the Philippines; the dance suites are original pieces choreographed and directed by the students. The main thread running through the culture night performances is a skit, which engages some aspect of Pilipinx-American identity. Theodore S. Gonzalves writes that culture nights provide opportunities to learn Pilipinx history—and for many student participants, history that they otherwise would not encounter. PAC’s event marked an anniversary year for the club, so the skit was set in the 1970s at the club’s founding at UCI. The story followed first-year students from both Southern California and the Philippines who are struggling to find Pilipinx community in their new university environment. Culture nights, in tandem with other more frequent student gatherings and performances, show how college students are rhetorically asserting their belonging—to the cultures with which they identify, to the university community, and to one another. These groups’ self-sponsored, embodied learning privileges the knowledges that these students find important, sometimes in contrast to what they feel their coursework has valued.

Matthew of PAC aspires to be an Asian American studies professor, and so he sees his club participation (e.g., public speaking, organizing and leading educational events) as part of his career path into academia. He said that he observes his professors’ teaching styles and reflects on how he might apply these approaches in PAC. Matthew explained that his personal, extracurricular, curricular, and professional commitments overlap, saying, “It means a lot to pass on this knowledge.” One of AAC’s coordinators also reflected on how his coursework has altered his perceptions of extracurricular activities. He commented that the Asian American churches he knows are “fairly conservative, so we don’t talk about issues like race, for example. . . . Asian American Christians don’t talk about social issues.” He had become more aware of this disconnect recently through his college coursework and said that he wished these issues were talked about more in the Asian American Christian spaces, including AAC, that he frequents.

Max’s curricular learning productively informs her efforts with PAC. In a general education course called Protests, Revolutions, and Movements, Max began to recognize the possible pitfalls in activist organizing. She explained that these lessons have informed how she leads PAC: at the club’s mental health workshop, she realized that it would be crucial to connect members to resources and people from UCI’s counseling center. In one of her lower-division writing courses, Max reflected on her racial and ethnic positionalities and argued for the need for better data on Asian American and Pacific Islander populations in the U.S. She explored issues of domestic violence among particular Asian communities and Asian American groups’ differential relationships to colonization. She noted that, despite these illuminating classroom experiences, she did encounter pervasive curricular Euro- and white-centrism.

Students’ efforts to combat what they see as cultural erasure generate opportunities for belonging. In this desire to “be long” to one another and within the university and social fabric, students often discover that they in turn desire to “be intersectional” in order to better understand and communicate their concerns. SADSA’s t-shirt design speaks to these impulses (Figure 2). Featuring landmarks and symbols from each of the eight South Asian nations, the pictorial elements emphasize SADSA’s position as a transnational coalition of students. The quotation from Indian-American filmmaker Mira Nair highlights collectivity and literacy: if “we” (the student group members) don’t “tell our stories” (e.g., educate one another and work for spaces and feelings of belonging) “no one else will.” Morris Young characterizes this transformative power of narrative as a re/visioning. For example, he describes how his students’ experiences of reading and writing literacy narratives “provides them with a way of understanding that literacy, race, and citizenship are both personal and public experiences, intertwined intimately and inextricably” (166). UCI student club members’ activities often rewrite cultural scripts to increase members’ understandings of self but also to circulate more nuanced depictions of Asian Americans.

Figure 2. SADSA’s t-shirt design.

Figure 2. SADSA’s t-shirt design.

Since I conducted my study, there is renewed exigence for examining how Asian American students rhetorically position themselves. The U.S. continues to see high profile instances of anti-Asian sentiment and violence spurred in part by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this prejudice is knit into the fabric of U.S. race relations, even when it fails to make headlines. Crucially, Asian American activists are connecting these incidences to the historic and current oppression of Black Americans. In early 2021, I followed up with Ligaya, who had refocused her extracurricular efforts into labor organizing over the past two years. She acknowledged her privilege as an Asian American at protests in that she does not face the same threats of arrest and violence as her Black peers. She also emphasized the importance of understanding that activist efforts extend beyond the time during which students may participate, saying there can be “years of organizing before we even get a glimpse of a movement.” Ligaya’s rhetorical education mirrors that of her UCI predecessors, such as Rice Paper writer Michelle Ko: both young, Asian American women long to belong to a broader community of social justice advocates.

SADSA, PAC, and AAC all aim, to varying degrees, not only to pluralize representations of Asian Americans but also to struggle collectively with the ways these plural positionalities run up against systems of power. This is what makes their efforts to “be intersectional” aspirational. Student club members continually revise intragroup and external positions—a process of navigation that constitutes their self-sponsored rhetorical education. While we, as scholar-teachers, cannot replicate precisely the complexities of this education, we would do well to remember that our students are communicators in multiple settings, with different motivations, strategies, and goals. Attending to the local and regional context, especially as it bears on racial and cultural histories, is also crucial to a feminist pedagogy. When we make space for outside knowledges within our classrooms, we affirm the value of the extracurricular to the curricular, and vice versa, enriching what we and our students learn from and with one another.

End Notes

- All names of twenty-first-century student organizations and respondents are pseudonyms. -return to text

- The Combahee River Collective’s 1977 “A Black Feminist Statement” provides the basis for how I define intersectional feminism: “we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking” (15). As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor writes, we ought to recognize how Black feminism has more recently “reemerged as the analytical framework for the activist response to the oppression of trans women of color, the fight for reproductive rights, and, of course, the movement against police abuse and violence” (13). -return to text

- Throughout this article, I employ “Asian American” to describe the student groups with which I have spent time in order to emphasize their embeddedness in the American university context. I want to note as well the valence of “Asian American” as a politicized identity, which 1960s and 70s activists claimed as an assertion of their belonging within American society and therefore deserving of the same rights afforded to white Americans. -return to text

- In 2016, the number of Asian residents surpassed those of white ones in Irvine. An article in the local news outlet, Orange County Register, asserts that Irvine is “the largest city in the continental United States with an Asian plurality” (Shimura and Wheeler). -return to text

Appendix

Basic interview questions:

-

- What motivated you to join this student organization? What has inspired your continued participation?

- What role(s) do writing and speaking play in your involvement with this club?

- How do you define your club’s cultural orientation?

- What are your club’s main goals? For example, how does your club aim to impact individual members, the campus community, or larger local, regional, national, or transnational communities?

- Do you see any connections between your club activities and work you’ve done for courses at UCI? Any connections to what’s expected of you in job or internship situations? -return to text

Works Cited

- Alexander, Jonathan, and Susan C. Jarratt. “Rhetorical Education and Student Activism.” College English, vol. 76, no. 6, 2014, pp. 525–44. -return to text

- Berg, Tom. “Why Westminster? Eleven Reasons the Vietnamese Came to Little Saigon – and Why They Stayed.” Orange County Register, 30 Apr. 2015. Republished on Viet Stories: Vietnamese American Oral History Project, University of California, Irvine, https://sites.uci.edu/vaohp/2015/04/30/why-westminster-eleven-reasons-the-vietnamese-came-to-little-saigon-and-why-they-stayed/. -return to text

- Carrillo Rowe, Aimee. “Be Longing: Toward a Feminist Politics of Relation.” NWSA Journal, vol. 17, no. 2, 2005, pp. 15–46. -return to text

- Fishman, Jenn, et al. “Performing Writing, Performing Literacy.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 57, no. 2, 2005, pp. 224–52. -return to text

- Fraser, Nancy. “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy.” Social Text, no. 25/26, 1990, pp. 56–80. -return to text

- Gonzalves, Theodore S. “The Day the Dancers Stayed: Expressive Forms of Culture in the United States.” Kritika Kultura, no. 6, 2005, pp. 42–85. -return to text

- Hoang, Haivan V. Writing Against Racial Injury: The Politics of Asian American Student Rhetoric. U of Pittsburgh P, 2015. -return to text

- Hsu, V. Jo. “Afterword: Disciplinary (Trans)formations: Queering and Trans-ing Asian American Rhetorics.” Asian/American Rhetorical Trans/Formations, special issue of enculturation: a journal of rhetoric, writing, and culture, no. 27, 2018. http://enculturation.net/disciplinary-transformations. -return to text

- Lee, Stacey J. Unraveling the “Model Minority” Stereotype: Listening to Asian American Youth. Teachers College P, 1996. -return to text

- Mao, LuMing, and Morris Young, editors. Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric. Utah State UP, 2008. -return to text

- Monberg, Terese Guinsatao, and Morris Young. “Beyond Representation: Spatial, Temporal, and Embodied Trans/Formations of Asian/American Rhetoric.” Asian/American Rhetorical Trans/Formations, special issue of enculturation: a journal of rhetoric, writing, and culture, no. 27, 2018. http://enculturation.net/beyond_representation. -return to text

- Moss, Beverly J. “Ethnography and Composition: Studying Language at Home.” Methods and Methodology in Composition Research, edited by Gesa E. Kirsch and Patricia A. Sullivan, Southern Illinois UP, 1992, pp. 153–71. -return to text

- National Center for Education Statistics. “University of California-Irvine.” College Navigator, https://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator/?q=uc+irvine&s=all&id=110653. Accessed 30 Apr. 2021. -return to text

- Rice Paper. Asian American/Pacific Islander student newspaper. 1991–1997. LD 781 I7 E24. Langson Library Special Collections, UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, CA. -return to text

- Royster, Jacqueline Jones, and Gesa E. Kirsch. Feminist Rhetorical Practices: New Horizons for Rhetoric, Composition, and Literacy Studies. Southern Illinois UP, 2012. -return to text

- Schell, Eileen E. “Introduction: Researching Feminist Rhetorical Methods and Methodologies.” Rhetorica in Motion: Feminist Rhetorical Methods and Methodologies, edited by Schell and K. J. Rawson, U of Pittsburgh P, 2010, pp. 1–20. -return to text

- Shimura, Tomoya, and Ian Wheeler. “Asians Have Grown to Dominant Group in Irvine.” Orange County Register, 2016. -return to text

- South Asia and Diaspora Student Association (SADSA). “First General Meeting.” 8 Oct. 2019, University of California, Irvine. -return to text

- Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta, editor. How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Haymarket, 2017. -return to text

- Trinh, Justine. “The Beginnings of Activism for the Department of Asian American Studies at UCI.” UCI Libraries, 2017, https://special.lib.uci.edu/blog/2017/07/beginnings-activism-department-asian-american-studies-uci. -return to text

- Wells, Susan. “Rogue Cops and Health Care: What Do We Want from Public Writing?” College Composition and Communication, vol. 47, no. 3, 1996, pp. 325–41. -return to text

- Young, Morris. Minor Re/Visions: Asian American Literacy Narratives as a Rhetoric of Citizenship. Southern Illinois UP, 2004. -return to text