“This Seismic Life Change”: Graduate Students Parenting and Writing During a Pandemic

“This Seismic Life Change”: Graduate Students Parenting and Writing During a Pandemic

Peitho Volume 24 Issue 2, Winter 2022

Author(s): Jessica McCaughey

Jessica McCaughey is an Assistant Professor in the University Writing Program at George Washington University, where she teaches academic and professional writing. In this role, Professor McCaughey has developed a growing professional writing program consisting of workshops, assessment, and coaching that helps organizations improve the quality of their employees’ professional and technical writing. Through this program, she has worked with organizations like Amnesty International, the FDA, the Democracy Fund, the American Legion, and many others on improving their writing processes and products. In her first career, she served as a writer, editor, and communications director in a variety of organizations. Her research focuses on the transfer of writing skills from the academic to the professional realm. In 2018, she was awarded the Emergent Researchers grant from the Conference on College Composition & Communication (CCCC). In that same year, she won the “Outstanding Article” prize from the Society for Technical Communication.

Abstract: This article documents and explores the feminist concern of graduate student and other parent-scholars during a particular time (the pandemic) and place (almost universally, their homes). Part narrative and part mixed-methods study, this piece investigates data from graduate student parents about their writing and home-life experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. It demonstrates the differing priorities and experiences of these scholars from their non-parent peers, including experiences of physical and mental health, productivity, and access to campus services and campus-community opportunities. Finally, I offer implications for future thinking and increased attention to graduate student parents, post-pandemic.

Tags: COVID-19, graduate students, parent-scholars, productivity, writingAs a parent and a doctoral candidate, I often tell people that I never imagined going back to school for a Ph.D., but if I had, I could not have dreamed that it would be my fourth or fifth priority (in the best of times), behind tending to my full-time faculty job, my daughter, my husband, my aging parents, and other obligations. And while I feel my life and teaching experiences have benefited me tremendously as an older returning student, I find myself wishing fairly often that I were younger, less encumbered, and that more of my life and my time were focused on my studies, as I see in some of my classmates. Instead, frankly, my doctoral work is something I have to fit in around other things and people that demand my attention. For instance, if I plan to study one evening and my daughter is sick,[1] I abandon studying. If a work crisis pops up, I attend to that instead of writing a paper for class. This has been even more the case since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Interruptions and competing priorities are literally in my line of vision at all times now. Although I hesitate to admit it here, my writing—both for my job and graduate work—has fallen even further down the list of priorities as I worry about my daughter’s isolation, the possibility of my husband being furloughed or laid off, our elderly parents’ immune systems, and my own sanity. Due to these limitations, my approach to such work has changed drastically and my standards for it have dropped, hovering now somewhere between “don’t embarrass yourself” and “just get it done.” I suspect this is the case for many graduate students—particularly those with children at home. Our ability to focus, broadly, is simply not what it was ten months ago for so many reasons.

Just a few months into the pandemic, I read an article in The Washington Post, in which two parents—both academics—tracked their child-related interruptions. They wrote of a 3-hour period of tracking:

Looked at one way, the situation appeared manageable: Over the course of three hours, the parent on duty was interrupted for a little over half an hour in total, meaning they got almost 2 1 / 2 hours of work time…But that time didn’t come in two clean chunks: The parent was interrupted 45 times, an average of 15 times per hour. The average length of an uninterrupted stretch of work time was three minutes, 24 seconds. The longest uninterrupted period was 19 minutes, 35 seconds. The shortest was mere seconds. (Edwards and Snyder)

The same article referenced a study that found it can take 20 minutes for a person who has been distracted from their work to come back to focus (Brumby et al.). Again, the longest uninterrupted work time for this particular writer was 19 minutes and 35 seconds.[2] Theoretically, my partner and I split our day around childcare, each taking either a morning or afternoon (pre-nap or post-nap[3]) working session while the other partner watches our daughter. Because she is two years old,[4] there is little to no independent time for her—unless we count watching TV on the couch while we sit next to her, trying to work or attend Zoom meetings. In reality, there has not been a single block of time without interruption in ten months.[5]

And it’s this experience that has led me to my research here. I ask: In what ways, if at all, are the experiences of graduate students who are parents different from the experiences of non-parent graduate students, particularly regarding home life and writing since the start of COVID-19?[6]

The “Incompatibility” of Parenting and Graduate Writing

The pandemic has, of course, changed every aspect of life for most people, from social gatherings and travel to parenting and public health overall. In higher education, the changes are just as drastic, and of course, for graduate students, in particular, educational challenges are heightened by all aspects of life outside of the classroom—even the virtual classroom.[7] Most graduate students work in addition to their studies—many full time. In “normal times” graduate student stress is well documented (see “Grappling with” and Puri). And during the pandemic that stress is increasing rapidly, ultimately developing for many into more substantial mental health issues. A study out of University of California at Berkeley reports that “32% of graduate and professional students screened positive for major depressive disorder” during the early months of the pandemic (Chirikov et al. 1). The study also notes, of course, that certain populations are much more likely to feel these effects—and they include caregivers in this set of specific populations. Caregivers in another study noted that they were most in need of “general coping” mechanisms (Fitzpatrick et al. 1088).[8]

B. S. Russell et. al conducted a study early in the pandemic about caregiver burden during COVID, finding that the impact of long-term and/or undefined periods of quarantining for families has the potential to “lead to unprecedented impacts on individuals’ mental health” (672). They write, “parents must actively plan new caregiving, work, and education routines, potentially compromising time to tend to their own emotional experience and self-care” (672).[9] Graduate students, then, must “actively plan” these new tasks into their days while also attending to their own educational routines.

We can assume that graduate students who are also parents make up a significant percentage of the overall graduate student population, although no recent data is available on this number. According to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, twenty-two percent of undergraduates are parents, and I think it stands to reason that this number is likely higher among graduate students, who are on average older (ASCEND); the average graduate student age is thirty-three (Who Graduate Students Are | Graduate Mentoring Guidebook | Nebraska).

Parenting during graduate studies or in a full-time academic job has always been fraught. While mothers in academia have done important work in making these complexities visible and noted, these have mostly been through narratives, and straight, white-middle class mother narratives at that (Rose). Few data-driven studies have examined the nuances and challenges of parenting while working as an academic, but it’s clear that finding time, energy, and focus particularly to write at all is extremely challenging in most cases, to put it mildly. Graduate student parents have always reported completing much of their studying and writing for school at night and on the weekends (Sallee 406). They also report spending less time on coursework than they would like or feel obligated to due to competing childcare demands (Sallee 406), particularly as quality childcare has always been out of reach for on graduate students’ salaries/stipends (Springer et al. 447; Theisen et al. 53). Candice Harris et al. write “Family is perceived by some to be invisible in academia,[10] although women often perceive motherhood to have a considerable impact on their academic career, as the amount of work required to be a successful academic can only be done when one is without children or other responsibilities” ( 709).

What we do know is that there is an underrepresentation of graduate student mothers in Ph.D. programs and some have referred to this as a social justice issue (Kulp 408). Alessandra Minello, Sara Martucci, and Lidia Manzo point out that “the beginning of an academic career is marked by a prolonged period of precariousness, one which typically coincides with a woman’s reproductive period” ( 2). Mothers who have a doctoral degree are also are not as likely to come from top-ranked programs or to publish scholarly work (Kulp 410). One study of parents in academia, centered around identity and performance, quotes a mother remarking on her colleagues and academia at large: “There is still an assumption that a parent can separate themselves from their children and come to work…especially a very young child…they just have to turn the switch off and I don’t think you can” (Harris et al. 712).[11] Amanda Kulp writes that “Graduate school is a critical period for Ph.D. earners to collect the kinds of resources they need to compete for tenure-track jobs, and parenting a child during graduate school can put stress on graduate students in their efforts collect these resources” (410).

For mothers working in STEM particularly, concerns around gender inequality that have always existed have now risen too. A “new motherhood penalty” places further distance between mothers and their non-mother and male colleagues in STEM, particularly, although certainly also those in other fields (Staniscuaski et al. 724). Kristen Springer, Brenda Parker, and Catherine Leviten-Reid found that

there are few formal institutional supports tailored to the needs of graduate student parents; there is limited knowledge on the part of faculty regarding supports that may exist for graduate students with children; and departments accommodate graduate student parents on a flexible,[12] case-by-case basis. All three serve to create a message that children are not a standard feature in the lives of doctoral candidates. (441)

Motherhood in academia[13]—whether as graduate students or faculty members—has always had to be strategic choice (Harris et al. 709). Springer, Parker, and Leviten-Reid write, “being both an academic and parent is quite incompatible in practice” (436)—and they were writing pre-pandemic.

It’s no wonder, of course, that Minello, Martucci, and Manzo in their very recent, very powerful study on the pandemic and academic mothers report that academic work is (still) “incompatible” with full-time parenting (2). I think most parents would admit that when they are parenting young children, it can be very difficult to be fully focused on work, even when their child is not physically in their presence. And now, they are fully in our physical presence at all times. For all parents, of course, both household work and childcare commitments are overwhelmingly up.[14] Although much has been rightly made of women disproportionately taking on caregiver loads, one recent study found that there was a much bigger gap in researcher productivity between those who have children and those who don’t than between genders (Breuning et al.). It’s worth noting that they also concede that, just the same, “women will be worse off when the dust settles from the pandemic” (Breuning et al. 2). It’s parenting more than gender, even, that makes keeping one’s head above water as an academic during the pandemic nearly impossible.

When it comes to expectations for research and publishing, some institutions are beginning to make concessions for faculty, but graduate students seem to be on their own (Guatimosim). Early studies suggest that “the global pandemic is quite likely to influence scholarly productivity during this period and in the months, and possibly years, to come” (Breuning et al. 2).[15] Reporting on a study of Canadian graduate students, Christine Ro notes that “Just over three-quarters of the 1,431 respondents report that the pandemic has ‘notably’ impeded their ability to conduct research.” 44 percent of those graduate students worry that the pandemic will impact their chances at completing their degree (TSPN). I have to believe that this sentiment is common beyond the bounds of this study.

Further, some argue that “writing needs concentration and inspiration that cannot be constrained into a limited time of the day” (Minello, Martucci, and Manzo 7). Very few studies have looked at the experiences of graduate student writers (Henderson and Cook 49), but even pre-pandemic, graduate student writing is a challenge. Brian Henderson and Paul Cook report that “a significant gap exists between what graduate students know and what they are expected to know” (49). And of course, different fields are going to hold and manage expectations very differently. For instance, in engineering, graduate students, “often struggle to learn to write under high-pressure conditions” (Berdanier and Zerbe 138). Such conditions are typical in many programs. Catherine Berdanier and Ellen Zerbe write:

…it is interesting that most students do understand that writing is a knowledge- transforming process, while still struggling with the trifecta of perfectionism, procrastination, and writer’s block. Leveraging writing strategies to overcome some of these issues, such as accountability structures, timed writing sprints, and time management techniques can be housed within a broader discussion of learning-to-write and writing-to-learn as a graduate student in the process of becoming a member of a discipline, calling to mind academic literacies theory. (133)

One might reasonably assume that writing expectations, especially towards professionalization, are more explicitly understood by graduate students in writing studies, but even in this discipline, Henderson and Cook’s work shows us that writing studies graduate students still feel they need clearer expectations (63). As we think about parenting, graduate students, writing, and the pandemic, we see a number of connections and crossovers, and yet, we don’t yet see any scholarship about parents who are graduate students writing during the pandemic.

Population and Data Collection

The research that follows draws from a larger data set collected by graduate students in a research methods class[16] at George Mason University. This IRB-approved (IRB 1557945-1), mixed-methods project included a survey and a limited number of interviews, conducted via video conferences due to the pandemic. All survey participant and interviewee identifying information has been made anonymous, per our IRB approval. The survey contained 27 questions, and a call for responses was distributed nationally, primarily via professional and academic listservs and social media. Due to the listservs we had access to, a high percentage of the respondents were in programs related to English or writing studies (68% of nonparent and 55% of parent respondents were in a writing and rhetoric or related program). However, a variety of other disciplines were represented, including, for instance, information systems, art history, Russian studies, law, consumer behavior and family economics, and genetics, just to name a few. Degrees being pursued included M.A., M.F.A, J.D., and Ph.D. Of 397 survey responses, six were single parents and fifty-three noted that they lived with a partner or spouse and their children, making a total of fifty-nine parents who answered the survey and 275 nonparents. An additional sixty respondents chose not to answer the question of who they live with, and so the answers from these participants were disregarded for the purposes of this inquiry. The total number of survey respondents I looked at, then, was 336. Of those, fifty-three percent of nonparents were still in coursework, and sixty-one percent of parents were still in coursework. Of both nonparents and parents, the vast majority of respondents were in Ph.D. programs and M.A. programs.

The interview contained sixteen open-ended questions. The interviewees were drawn from survey respondents who indicated that they were willing to be interviewed. In the interviews, only four of the twenty-five interviewees mentioned having children, a smaller percentage than replied to the survey, presumably because parents have less time to spare to volunteer to be interviewed.

Mental and Physical Health

Physical and mental health has been a major concern during the pandemic, for reasons that span the stress and isolation and the closing of gyms and the complexities of exercising with social distancing in place to issues of lost wages, the illness and death of family, civil unrest, and so many other factors. Approximately half of each group reported major or moderate impacts to physical health during the pandemic.[17] Of the survey respondents, fifty-four percent of parents stated that they have accessed health and/or wellness resources during the pandemic, compared to thirty-nine percent of nonparents. Interestingly, more nonparents reported major or moderate impacts to mental health, seventy-two percent compared to parents at sixty-two percent. Parents reported a slightly higher impact than nonparents on work-life balance (eighty-three percent to seventy-four percent), but both groups reported major impacts here in high numbers. Only fourteen percent of nonparents expressed high impacts from caretaker expectations, compared to fifty percent of parents, although this fourteen percent reminds us that “caretaking” takes many forms. Several survey respondents and interviewees mentioned drastic life changes and particularly strict quarantining due to elderly or immune-compromised relatives that they cared for.[18]

Parents in interviews also talked quite a bit about the lack of “alone” time they experienced[19] due to balancing graduate work, childcare, and, usually, also a job, all within the confines of their home:

My biggest thing is just childcare, and I mean that has really been the big shift for me […] while both kids are understandably in the middle of the meltdown because we’re in a pandemic and they haven’t seen their friends, and I’m just sitting there thinking, like, [this would] be so much easier if they were in school every day. You know, like I could get a little time to myself. So that’s really the biggest the biggest one for me. (Anonymous Interview Participant 28)

Ironically, they also, sometimes in the same breath, discussed the challenges of isolation:[20]

The isolation was definitely like a struggle, especially without the childcare that—I already—I am an introvert, and I do kind of recharge by having alone time. But even I was kind of starting to hit my limit on the amount of hours a day and days a week that I could spend with only an eight month old to talk to (Anonymous Interview Participant 3)

They[21] are with their[22] children every second, but never with colleagues. Such issues of space and home, of lack of access to offices, classmates, and colleagues, while central to these conversations about sanity, don’t even touch on the limits these situations place on gaining access to feedback or even casual what-are-you-working on conversations, which most scholars I think would agree are often incredibly valuable to our work.

Productivity

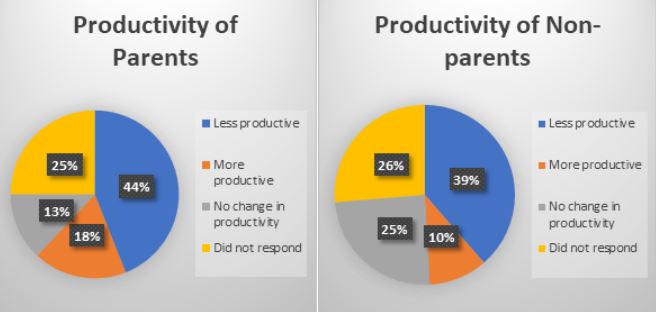

Productivity is, of course, a major concern for any graduate student, but for parents during the pandemic, such concerns are certainly heightened. Interestingly, Figure 1 below, which charts perceptions of productivity since the start of COVID-19, shows us that parents and non-parents alike are struggling to similar degrees; exactly forty-four percent of each group perceived that they are less productive since the start of the pandemic. We don’t, of course, have data on whether these perceptions are accurate and/or the degrees to which productivity might have suffered.

Figure 1: The first pie graph, titled “Productivity of Parents,” shows that almost half note that they have been “Less Productive” during the pandemic. In the second pie graph, titled “Productivity of Non-parents,” that pie slice is slightly smaller. Interestingly, the “Parents” graph also shows that a slightly larger percentage stated they were “More Productive” during the pandemic than non-parents.

Related to this question of productivity, in answer to the question, “Is there anything else about your graduate writing life during the COVID-19 pandemic that you think is important for us to know?” perhaps unsurprisingly, most parents who responded to the survey wrote about having their kids home with them, and the toll twenty-four-hour care and home-school supervision took on them and their work. Representative responses include:

The hardest, most difficult aspect for me is that public schools are closed, so both of my kids are at home full time and it’s impacting my time to get both work and school done. I teach a 5/5 load at the university where I’m a full-time lecturer, plus am taking graduate coursework, and the original plan is that my kids would be in school. This really threw a wrench in things! (Survey Participant 244)

My situation feels a little unique in that I was a full-time caregiver of two children from March-September. My boyfriend’s children moved in with us and I had to manage them for the duration of the spring semester and all of summer during a research fellowship. My writing process and workflow changed dramatically due to being a full-time parent. (Survey Participant 7)

Keeping up with the demands of family and work mean my graduate writing is significantly diminished. (Survey Participant 19)

…not a whole lot got done, because my days were devoted to just trying to keep track of a crawling infant and keep him happy and kind of keep on top of stuff. (Anonymous Participant 3)

We see that for these caregiving graduate students, writing “changed dramatically” as the hours of each day being allocated previously to writing were now necessarily devoted to the work of caring for kids. And no wonder; if a parent works an eight-hour day and commutes, the average toddler likely spends around nine hours in daycare each weekday, and school children are often gone somewhere in the range of seven hours. Those seven to nine hours are now time that parents need to feed and supervise their children. Even high school students, who require less “supervision,” require time and attention during the day from their caregivers. As one respondent put it, “[my writing] is more impacted by the fact that my daughter is at home all of the time since high school is not meeting face to face; her mental state and her ability to work at home colors my ability to work at home” (Survey Participant 289). To keep up productivity, these parents have to find writing time elsewhere.[23]

In the limited number of interviews from parents, we found that external childcare was a topic of concern that related to many questions. The narratives from these interviews reinforce how much graduate student parents rely upon safe, consistent childcare and schooling for their children in order to write and work. Some representative comments included:

So actually, the biggest [challenge] is childcare. I have a 10-year-old, and I have a four-year-old. And so when I originally signed up for my Ph.D. program, I was like, oh, now is the perfect time, right? Like my four-year—in Fall 2020…my four-year-old will be going into preschool, so will be in school for like four hours a day, five days a week. My 10-year-old is going into fourth grade. He’s in school for eight hours a day. My eighty-year-old grandparents come up twice a week and they spend the night with us, and they take care of the kids […] I can take two classes no problem. And then COVID happens. (Anonymous Participant 12)

For the first six months of the pandemic, we had my partner’s kids here with us full time, and I needed that flexibility to get through the summer, and my summer work, because I had to take care of them during the day, like watch what they were doing, like make sure they’re alive and fed, and have things to do […] I went through this seismic life change of becoming a full-time guardian, and going online, like the same week. (Survey Participant 7

Childcare was probably the single biggest issue. I think if my son had still been able to go to daycare through everything, even if I couldn’t go to the library, even if I couldn’t go pick up materials, I could have still gotten a decent amount done. Maybe had a little bit of a lapse in productivity. But that was the—the single biggest one is just you can’t—with one that little—you can just sit, you know, you can’t even say like, well, go play in your room for a little while. It’s like, you’re eight months old, you’re into everything. And it’s just a constant, kind of keeping track of him (Anonymous Interview Participant 3)

Managing home school is a particular concern[24] for many of the interviewees as well:

I went from like, oh, I have this three-hour block of time where I can just write and write and write and write to like now I’m like, alright I get a 20 minute burst, and then my older son gets locked out of Zoom and I have to run in there and help him and then I come back and do another fifteen minute burst and then […] there’s no boundary right now, and it’s just a very different space to be in to try to get work done. (Anonymous Interview Participant 11)

Nonparents, on the other hand, wrote about a variety of other issues that affected their writing productivity: including isolation, anxiety, a lack of focus, increased screen time, challenges of remote collaboration and remote teaching, the less-than-ideal physical spaces they have to write in, and uncertainty about the job market. We might assume that these were concerns shared by the parents, but that childcare and parenting concerns simply took precedence.

Access to Campus Services and Campus-community Opportunities

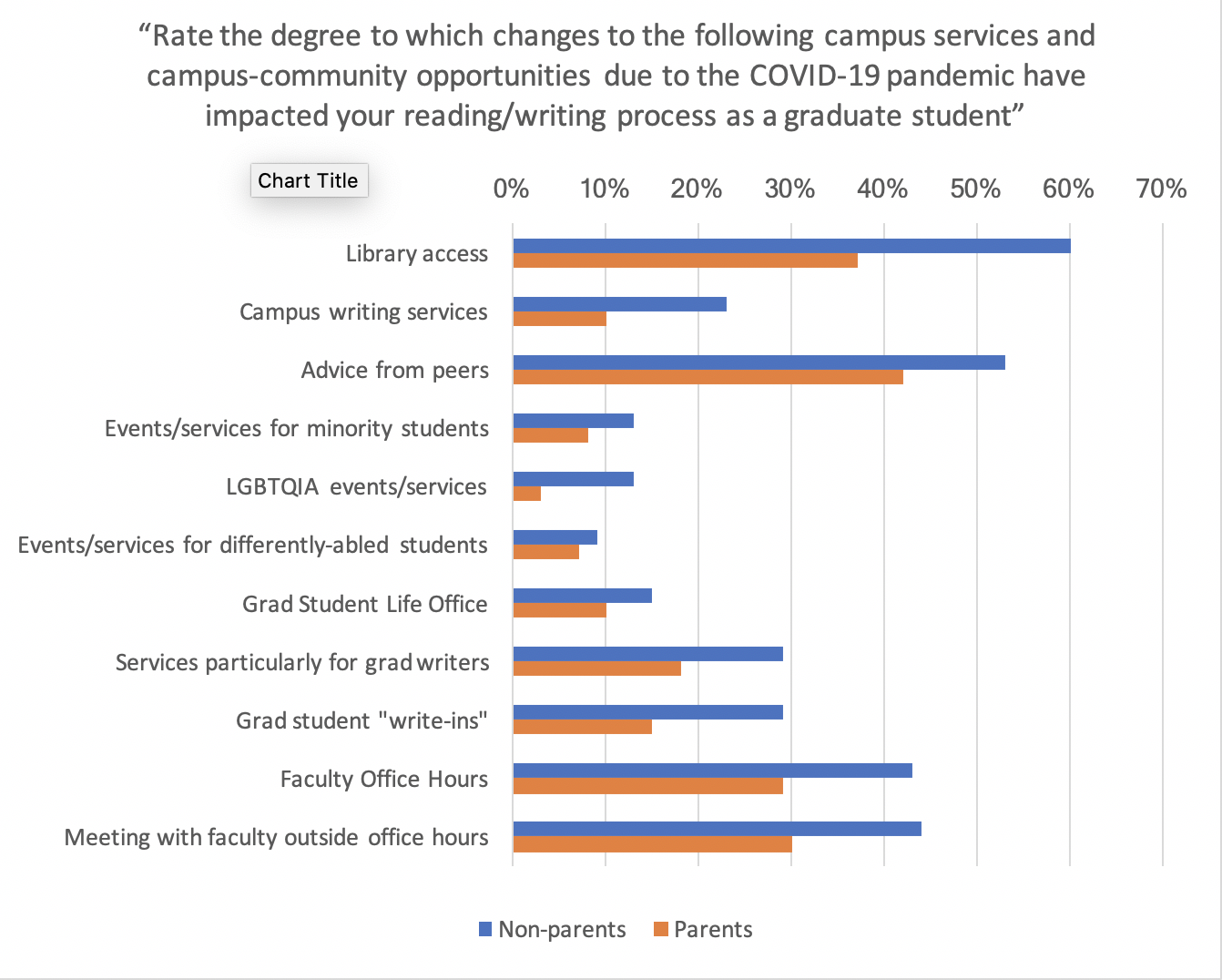

One of the most illuminating sets of data in this survey regarding parents relates to access to campus services and other on-campus opportunities for graduate students. Figure 2 below illustrates parent and non-parent responses when asked to rate the degree to which COVID-19-related changes in such services and opportunities have impacted their reading and writing work.

Figure 2: Horizontal bar chart demonstrating that for all categories non-parents reported a higher impact on their reading and writing processes by a lack of access to services. The chart is titled “Rate the degree to which changes to the following campus services and campus community opportunities due to the COVID-19 pandemic have impacted your reading/writing process as a graduate student. The chart shows non-parents (in blue) were most impacted by library access at 60%, advice from peers at 55%, faculty office hours at 45%, and meeting with faculty outside of office hours are 45%. The charts shows parents (in orange) were most impacted by advice from peers at just above 40%, library access at just above 35%, meeting with faculty outside of office hours at 30%, and faculty office hours at just under 30%.

We can see that parents were less effected in every single category above. This chart shows us that parents were then, presumably, taking less from such campus services to begin with. And yet, interestingly, of nonparents, thirty-seven percent explicitly said they felt supported as a graduate writer by their “institution, department, program, and/or campus community,” compared to fifty-five percent of parents—perhaps because they have the time to access such support.[25

Insights for the Future

In May of 2021, a photo of an MIT professor went viral after he purchased a crib for his office to support his graduate students with babies or small children (“Mass. Professor Goes Viral After Putting Crib in Office to Help Grad Student with Infant Daughter”). He was praised, but then, quickly, commenters shifted to lament the lack of large-scale, systemic help for parents in general, and graduate students in particular.[26] As we see in the literature above, mothers who are graduate students suffer in uncountable ways. They’re disadvantaged as students and if we measure success by what kind of job they’re able to land post-graduation, such disadvantages and lack of support will continue to impact them throughout the rest of their career.[27]

This data and these insights from this study aren’t likely to change much about our current situation or the larger one; there’s no vaccine buried in them, and there’s no rhetoric to make millions of COVID-deniers start wearing masks.[28] But if nothing else, it’s my hope that part of what comes out of this study and others like it is that both parents and non-parents alike can recognize both these systemic issues and the enormous toll COVID-19 is taking on our work. And I hope that advisors and the faculty overseeing these students and programs can too. Well over half of the participants in both data groups reported major or moderate impacts to their mental health since the start of the pandemic,[29] and as we’ve all experienced in some way or another, the other challenges and tragedies of life don’t stop just because we’re stuck at home. Elderly family members still have heart attacks. Work is still busy. The car still breaks down.[30] The stresses of life are already high for most of us, in particular graduate student parents.

And while I hate to generalize, I believe that most of us would assume such dilemmas affect mothers more than fathers. Right now, more broadly, women’s unemployment is far outweighing the unemployment of men (Ruppanner et al.)—almost certainly as this relates to motherhood—and I imagine only time will tell, too, how many graduate programs, also disproportionately of women, are interrupted or fully stopped due to childcare, as we might assume from a recent census piece (Heggeness and Fields). It’s crucial that we change expectations, educating on what life is like for parents right now so that we lose fewer of them through the “leaky pipeline” but also so that our writing can measure up to our peers.

In one of my favorite interviews, a graduate student told me that her kids were grown, but that the two who were college-aged were at home with her due to the pandemic, rather than away in a dorm, as they’d all expected. She told me that they’ve been keeping her in line, and even reading her work and offering her feedback on her papers.

Unfortunately, of course, this is a rare case. As the data shows, most graduate students—parents or not—are struggling in any number of ways.[31] But they were also struggling before the pandemic, as so much of the scholarship I explore above shows.

To that end, finally, I’m most interested in this data as I believe that it tells us something larger about graduate students who are also parents during “normal” times. As I look back to Figure 2 above, I’m struck by how graduate students who are also parents operate, write, and work differently than non-parent graduate students. As we see, parents reported being less affected by the loss of every single type of in-person campus and program-related resources that had disappeared during the pandemic, from faculty office hours to services for grad writers from other offices or departments. Again, this suggests to me that these parents have been less reliant on such services and support even pre-pandemic. I am a parent in a Ph.D. program, but during my M.A. and M.F.A., I was not a parent. I can say with certainty that I spent more time on campus with faculty and peers and that I took advantage of my university’s additional graduate student support much, much more during my time enrolled in these earlier programs. Without children and working as a teaching assistant, I had the time to; my graduate work was my priority. In my Ph.D. program, however, even pre-pandemic, nine times out of ten I deleted emails advertising workshops, talks, and other opportunities for graduate students. I felt I had little time to spare—even for often seemingly very worthwhile activities—and even if I did feel like I had the time, I often couldn’t bear the thought of asking my partner to do dinner/bath time/bedtime alone yet another night of the week beyond the evenings I attended class.[32] It feels crucial to me that institutions find ways to better accommodate other graduate students in similar positions.

I think that seeing all of this should allow me to simply give myself a bit of a break.[33] Truthfully, the tension between wanting to go easier on myself as a parent, student, and employee, and the still very real deadlines and responsibilities are in many ways irreconcilable—and to me this data suggests that this was the case even pre-COVID. But it’s my hope that even if graduate students are largely “failing” at writing, we can better accept our limits and the limits imposed by the pandemic—but also the system as a whole.[34] Because it seems clearer than ever that the system(s) aren’t going to change for us.

Footnotes

[1]Or overly tired. Or missing me. Or hungry for something different than her dad knows how to make. Or interested in taking a walk. Or sitting in the backyard eating popsicles.

[2]It’s probably worth noting that it took me four days to simply get through this brief article.

[3]Since initially writing this, she’s stopped napping. STOPPED NAPPING ALL TOGETHER no matter how long we stroke her hair and talk in quiet voices and get her up early and schedule pre-nap quiet time.

[4]Now three, likely four at the time of publication. Look, it’s a pandemic and a I have a toddler, so yeah, fully researching, writing, and revising this thing has been a long process.

[5]Make that 19 now!

[6]Other than, you know, nonparents probably sleep and occasionally watch Netflix and likely have clean-ish hair and don’t find a slice of bell pepper at the bottom of their cold, cold coffee mug at noon when they finally finish it.

[7]And obviously high schools. And middle schools. And elementary schools. And don’t even get me started on the unexpected shame of having the only toddler who won’t sit still for Zoom story time in April 2020, despite me literally bribing her with snacks. And it’s a screen! Why isn’t it captivating like all the screen-based garbage that she can’t look away from?

[8]But what would that even look like right now? We don’t have the hour for therapy, even those of us lucky enough to have insurance. And if we did, every therapist I know is booked up because everyone is falling apart. What other strategies might I be attempting to employ? Last week my daughter tried a Sesame Street deep breathing exercise at a particularly rough moment. But I wouldn’t call that a long-term solution…

[9]And by “self-care” we’re rounding down now to teeth brushing.

[10]To put it truly as mildly as possible.

[11]And the thing is, I really try. I apologized to my professor so hard and so many times the night I had to leave a Ph.D. seminar because my husband called to tell me the baby had spiked a 104-degree fever and had thrown up in every room of the house in the hour since I’d left. The shame of it, leaving class to go to the Emergency Room.

[12]Flexible? Says who?

[13]Or, you know, ANYWHERE.

[14]It was a few months into the shutdown when I calculated the number of meals and snacks I made, plated, and cleaned up after weekly for my toddler during the pandemic, and I no longer have that number because I can’t find anything in this mess of a house, but it was a lot.

[15]And after this, will we ever look at how just parenting in normal times impacts “productivity” when compared to non-caregiver colleagues?

[16]I mean, obviously I couldn’t have planned this, gotten IRB approval, recruited, and developed the study materials alone. My role in collecting the data wasn’t huge. Even analyzing the data felt like an insurmountable task most nights as I looked with bleary eyes at my Excel sheets after bathing this kid and reading six books and sitting with her until she fell asleep in the dark without actually falling asleep myself.

[17]I actually would have guessed parents would be in better shape at this point because we’re always chasing the kids to save them from death in the street and chasing them to wear them out so they’ll sleep and chasing them because the neighbors would for sure think she’s too small to be five houses down alone on the sidewalk.

[18]Can you even imagine caring for a toddler AND an elderly parent in your home right now? (Surely some of you can and are!) For that matter, I only have ONE kid! How am I even complaining?

[19]That’s not necessarily true for me. I did a lot of crying alone in the bathroom while my daughter watched Bluey.

[20]Never alone and also isolated feels right on target.

[21]We

[22]our

[23]And in my home and many others, “elsewhere” means after bedtime.

[24]Sweet Jesus, I can’t honestly even imagine.

[25]“Perhaps,” but, you know, definitely because of this. After working all day and being away from my kid, and knowing I have to be in a classroom again at 7:20 p.m. for a graduate seminar, I’m not going to skuttle over to campus early to check out the resources at the Random Campus Opportunity.

[26]We see versions of this all the time; the professor with a student’s baby strapped to his or her back is another recurring example.

[27]It’s not within the scope of the research here to consider the cost and quality of childcare in the U.S. during “normal” times, and yet, of course, it’s relevant. In most areas of the country quality childcare is nearly outside of the range of possible for homes with two working parents. What happens when one of those parents is bringing in only a pittance of a graduate student stipend?

[28]Or, now, as I revise this in late Fall 2021, convince these people to get the vaccine because COME ON, SERIOUSLY I STILL GOTTA BE WORRIED ABOUT THIS KID GETTING COVID. YOU’VE GOT TO BE KIDDING ME.

[29]More migraines. More panic attacks. More insomnia. More decision fatigue, driven by “Are we being too cautious or not cautious enough? Which is worse—that she’s getting super weird from lack of socialization or that her friends who went back to school might be exposed?”

[30]You still forget the milk. Your in-laws still need you to be sure to call Aunt so-and-so because she’s ill. A peach milkshake still spills all over the car.

[31]As a person who’s been lucky to only really rarely struggle with focus and “buckling down and getting to work” in my pre-pandemic endeavors, and as a student and employee who takes quite a bit of pride and identity stake in my ability to be productive, my life during the pandemic, here at home, a virus raging outside and a two year old/ three year old raging inside, my struggle to focus isn’t just a frustration; it’s becoming a spark to a larger depression brought on by feeling as though, well, what is the point? My rational brain is quick to remind me that, of course, work and productivity don’t equal value and there’s a pandemic and also my child is alive and fed, so that’s a win, and yet, I struggle, like so many of my peers. I hope that this data and analysis allows me to lower the bar lower for myself. I want to demonstrate, at least inwardly, that I can’t possibly meet those same standards I was meeting pre-pandemic. And of course, it’s worth noting, realistically, no one can, with or without kids; this data shows that everyone is struggling.

[32]During the pandemic, I don’t even open these emails; I just hit delete. And I have to believe I’m not the only one.

[33]But not, you know, really. Many months after initially drafting this, the guilt I feel is stronger than ever about the ways I’m failing my daughter.

[34]And the system is fucked. I mean, not just the academic system, although, yeah, for sure that is. But the SYSTEM-system is fucked, and that’s clearer than ever to anyone who wants to see it. Whether you clean houses or run a museum or grow flowers or wait tables or analyze stocks, if you are a mother, your life and time were never your own, but they are even less so now. As I write work on this revision, I am sitting on the toilet next to the tub where my daughter is soaking off a 102.5-degree fever. On a work day. And a school day. On day six back to daycare after 18-months home. There is no system in place that works for me, a working mother and graduate student, so earlier today I taught my class virtually, and the two quiet hours I had marked off to work on my dissertation evaporate into the steam of the humidifier while I soothed her. It will be all right, I tell her, but long-term, I’m skeptical. I imagine this little creature as an adult woman with her own child, with goals, even with a partner who does their fair share—and still, run ragged and exhausted by the tension between this drive and the lack of support.

Works Cited

Anonymous Interview Participant 3, Personal Interview, Oct. 2020.

Anonymous Interview Participant 11, Personal Interview, Oct. 2020.

Anonymous Interview Participant 12, Personal Interview, Oct. 2020.

Anonymous Interview Participant 28, Personal Interview, Oct. 2020

ASCEND, The Aspen Institute and the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. “Parents in College By the Numbers” 2020. https://iwpr.org/iwpr-issues/student-parent-success-initiative/parents-in-college-by-the-numbers/. Accessed 5 Nov. 2020.

Berdanier, Catherine, and Ellen Zerbe. “Quantitative Investigation of Engineering Graduate Student Conceptions and Processes of Academic Writing.” 2018 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (ProComm), IEEE, 2018, pp. 138-45.

Breuning, Marijke, et al. “The Great Equalizer? Gender, Parenting, and Scholarly Productivity during the Global Pandemic.” Political Science Education and the Profession. APSA Preprints, 21 July 2020, https://preprints.apsanet.org/engage/apsa/article-details/5f16fc5660b4ad001212f977.

Brumby, Duncan P., et al. “How Do Interruptions Affect Productivity?” Rethinking Productivity in Software Engineering, edited by Caitlin Sadowski and Thomas Zimmermann, Apress, 2019, pp. 85-107.

Chirikov, Igor, et al. “Undergraduate and Graduate Students’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” U.C. Berkeley SERU Consortium Report, Aug. 2020. escholarship.org, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/80k5d5hw.

Edwards, Suzanne M., and Larry Snyder. “Perspective | Yes, Balancing Work and Parenting Is Impossible. Here’s the Data.” Washington Post, 10 July 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/interruptions-parenting-pandemic-work-home/2020/07/09/599032e6-b4ca-11ea-aca5-ebb63d27e1ff_story.html.

Fitzpatrick, Olivia, et al. “Using Mixed Methods to Identify the Primary Mental Health Problems and Needs of Children, Adolescents, and Their Caregivers during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic.” Child Psychiatry & Human Development, Oct. 2020. pp. 1082-93

“Grappling with Graduate Student Mental Health and Suicide.” Chemical & Engineering News, https://cen.acs.org/articles/95/i32/Grappling-graduate-student-mental-health.html. 7 August 2017. Accessed 5 Nov. 2020.

Guatimosim, Cristina. “Reflections on Motherhood and the Impact of COVID 19 Pandemic on Women’s Scientific Careers.” Journal of Neurochemistry, Sept. 2020, pp. 1-2.

Harris, Candice, et al. “Academic Careers and Parenting: Identity, Performance and Surveillance.” Studies in Higher Education, vol. 44, no. 4, Apr. 2019, pp. 708-18.

Heggeness, Misty L., and Jason M. Fields. “Parents Juggle Work and Child Care During Pandemic.” The United States Census Bureau, 18 Aug. 2020, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/08/parents-juggle-work-and-child-care-during-pandemic.html.

Henderson, Brian R., and Paul G. Cook. “Voicing Graduate Student Writing Experiences: A Study of Cross-Level Courses at Two Master’s-Level, Regional Institutions.” Graduate Writing Across the Disciplines Identifying, Teaching, and Supporting, edited by Marilee Brooks-Gillies, et al., The WAC Clearinghouse, 2020.

Kulp, Amanda M. “Parenting on the Path to the Professoriate: A Focus on Graduate Student Mothers.” Research in Higher Education, vol. 61, no. 3, 2020, pp. 408-29.

“Mass. Professor Goes Viral After Putting Crib in Office to Help Grad Student with Infant Daughter.” MIT Department of Biology, 21 May 2021, https://biology.mit.edu/mass-professor-goes-viral-after-putting crib-in-office-to-help-grad-student-with-infant-daughter/.

Minello, Alessandra, Sara Martucci, and Lidia K. C. Manzo . “The Pandemic and the Academic Mothers: Present Hardships and Future Perspectives.” European Societies, Aug. 2020, pp. 1-13.

Puri, Prateek. “The Emotional Toll of Graduate School.” Scientific American Blog Network, Jan. 2019, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/the-emotional-toll-of-graduate-school/.

Ro, Christine. “Pandemic Harms Canadian Grad Students’ Research and Mental Health.” Nature, Aug. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02441-y.

Rose, Jeanne Marie. “Mother-Scholars Doing Their Homework: The Limits of Domestic Enargeia.” Peitho, vol. 22, no. 2, 2020, /article/mother-scholars-doing-their-homework-the-limits-of-domestic-enargeia/.

Ruppanner, Leah, et al. “COVID-19 Is a Disaster for Mothers’ Employment. And No, Working from Home Is Not the Solution.” Phys.Org, 21 July 2020, https://phys.org/news/2020-07-covid-disaster-mothers-employment-home.html.

Russell, B. S., et al. “Initial Challenges of Caregiving During COVID-19: Caregiver Burden, Mental Health, and the Parent–Child Relationship.” Child Psychiatry & Human Development, vol. 51, no. 5, 2020, pp. 671-82.

Sallee, Margaret W. “Adding Academics to the Work/Family Puzzle: Graduate Student Parents in Higher Education and Student Affairs.” Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, vol. 52, no. 4, 2015, pp. 401-13. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2015.1083438.

Springer, Kristen W., Brenda K. Parker, and Catherine Leviten-Reid. “Making Space for Graduate Student Parents: Practice and Politics.” Journal of Family Issues, vol. 30, no. 4, Apr. 2009, pp. 435–57. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X08329293.

Staniscuaski, Fernanda, et al. “Impact of COVID-19 on Academic Mothers.” Science, vol. 368, no. 6492, 2020, p. 724.

Survey Participant 7, Sept. 2020.

Survey Participant 19, Sept. 2020.

Survey Participant 244, Oct. 2020.

Survey Participant 289, Oct. 2020

Theisen, Megan Rae, et al. “Graduate Student Parents’ Perceptions of Resources to Support Degree Completion: Implications for Family Therapy Programs.” Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, vol. 30, no. 1, 2018, pp. 46-70. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2017.1382650.

Toronto Science Policy Network (TSPN). “COVID-19 Graduate Student Report.” Toronto Science Policy Network. https://tspn.ca/covid19-report/. Accessed 2 Nov. 2020.

“Who Graduate Students Are.” Graduate Mentoring Guidebook, UNLN. https://www.unl.edu/mentoring/who-graduate-students-are. Accessed 5 Nov. 2020.