The Blanks at Our Beginnings: A Graduate Student’s Reflection on Peitho’s Contributions to New Scholars

The Blanks at Our Beginnings: A Graduate Student’s Reflection on Peitho’s Contributions to New Scholars

Peitho Volume 24 Issue 4, Summer 2022

Author(s): Abby Breyer

Abby Breyer (she/her) is PhD student in Rhetoric and Composition at the University of Kansas where she also teaches sections of Composition I and II. Her current research is in the areas of digital rhetoric, literacy studies, social justice, and feminist methodologies and pedagogies.

Abstract: In the spirit of reflecting on ten years of Peitho, I seek to examine the extent to which this journal has accomplished its original goal to fill the blanks that continue to disrupt our histories. I combine narrative reflection of my own experiences reading the entirety of the journal and original newsletter, along with a content analysis that visually maps the most common trends in the journal’s scholarship using keywords, from each piece. The narrative follows my perspective as a graduate student learning the feminist methods and frameworks Peitho has produced and esteemed or the first time. Then, the analysis of topical trends serves as a starting point for reflection on where Peitho has taken us in the past and how it can continue to inform the scholars of the future.

Tags: content analysis, graduate student, keyword visualization, narrative, reflection, word clouds

Firgure 1: The front page of the first issue of what would become Peitho. The title says, “Newsletter of the Coalition of Women Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition.” There is a picture of the goddess Peitho on the left-hand side, and the volume begins with a letter from the editors.

As a graduate student just beginning my career in academia, I often feel overwhelmed by “blanks.” There is so much scholarship I don’t know, theories I haven’t mastered, methods I haven’t tried yet, and a series of spaces on my CV where more service, teaching, and publications should be. And yet, I can see something wonderful about an open space, about having the chance to find something interesting or new or forgotten and letting it spill into a crack that previously felt hollow. This drive to fill ourselves and our field with more knowledge, more stories, and more justice is why many of us became scholars in the first place, and why Peitho began the way that it did.

Though it is sometimes easy to get caught up in the pressure of filling our own “blanks,” Peitho serves as a reminder of the true goals that drive us as feminist scholars in the field of Rhetoric and Composition. In the spirit of reflecting on these goals and ten years of Peitho as an academic journal, I took the opportunity to read the entirety of the publication’s corpus, including the newsletters. I started with the first issue in 1996, then worked my way up each year to Winter 2022, which was the most recent issue at the time of my reading. The entire process took me about two months, and as I read, I kept detailed notes of my reading experience. These research memo-style notes took the form of reflections, affective experiences, important and memorable quotes, and questions spurred by the scholarship. By the time I finished, I had accumulated a little over 250 pages of single-spaced notes.

The whole process was a bit like drinking out of a firehose; there was just so much. I had a moment of panic about halfway through when I realized that this was only one journal in the field. I was practically drowning in information and was still only scratching the surface. But despite the panic and the overwhelming amount of new knowledge, I went on an incredible journey witnessing the breadth of Peitho’s scholarship. I am humbled by the work others have done before me, and I hope my reflection below captures how grateful I am to every scholar who has contributed.

In addition to helping me as a new scholar in the field, I also saw my reading as an opportunity to map the lineage of knowledge that has been produced through Peitho over the years. To accomplish this mapping, I tracked the keywords and tags used to organize each of the introductions, book reviews, articles, and essays by their main ideas and methods. For works that did not have tags, I used my notes and keywords in the titles to create my own so that every piece of writing would contribute to the overall total of words I collected1. Though this method was sparked by my interest in corpus linguistics, I was encouraged and guided by the work of Oriana Gatta who worked with similar methods in her article “Connecting Logics: Data Mining and Keyword Visualization as Archival Method/ology.”

After compiling a list of every keyword, I entered it into a word cloud generator to visualize the most frequently used words and phrases. In doing this work, I recognize the subjectivity of both my collection of some of the tags and my interpretation of how they should be included in the visual. Because of this, the mapping should not be viewed as a perfect representation of the topics of the journal, but rather as a starting place to discuss themes from the perspective of a new reader.

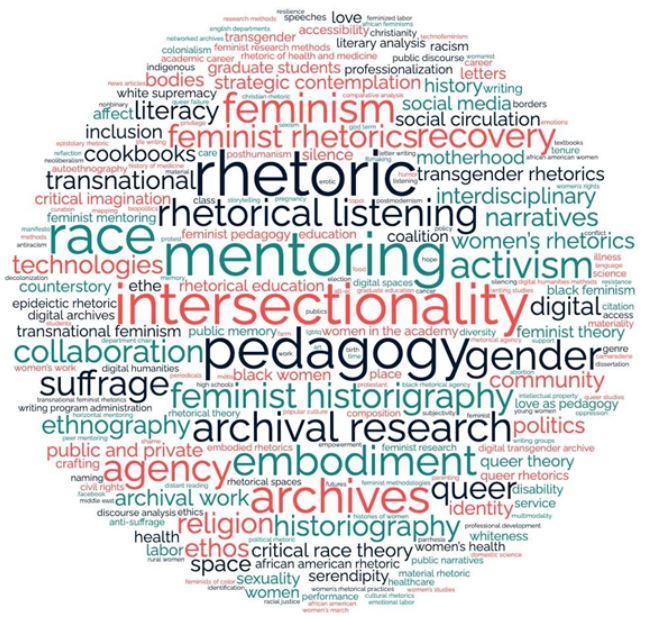

Figure 2: Hundreds of words fit together in a big circle of varying sizes and colors. Some of the largest words are feminism, rhetoric, recovery, mentoring, activism, race, technologies, intersectionality, pedagogy, gender, collaboration, suffrage, feminist historiography, digital, archival research, politics, suffrage, embodiment, agency, archives, queer, religion, and ethos. The cluster of words is circle-shaped, with the larger-font words in the middle and words in smaller font at the edges.

Figure 2 is the final visual I created from my word list, and includes the keywords that are used twice or more throughout all of the pieces published by Peitho. The overwhelming number of words in such a small space starts to capture the way I felt reading, and it also highlights some of the main topics of the journal in a quick snapshot. Using this word cloud as a starting point, my own narrative experiences can be combined with the data shown here to emphasize a few major takeaways.

On Mentoring

One of the largest words in the word cloud is “mentoring,” which is a theme that ran through both the original Peitho newsletter and the academic journal. The pieces that cover mentoring range from discussing feminist mentoring writ large, detailing the mentoring sessions at CWSHRC meetings, or delving into the specifics of certain types of mentors (Tucker) and certain types of mentoring (Nicolas, VanHaitsma & Ceraso, Ribero & Arellano). In one of my favorite pieces, Kirsten Benson and Casie Fedukovich write an ethno-poem about mentoring which showcases a back-and-forth exchange between mentor and mentee:

“Casie: You tell me you remember the sting of feeling this way. You tell me, the work before the work IS more of the work than I realize. I’m skeptical, but I listen. I’m resistant, but I start to hear, through pen edits, through long talks. You tell me, entering this field feels shaky. You tell me to keep going, that I’m getting it now. A little bit of success, a lot of failure, but I move forward…

Kirsten: …No one is expert to start off with. Move forward.

Casie: … No one is expert to start off with, you say. I trust, and I move forward. Slowly, but forward” (9).

The morning I began writing this section was the first day of my summer teaching. Before I could introduce myself or pull up my syllabus, a student in the front row raised their hand and asked me, “How did you get to be where you are?” I didn’t respond right away, struck silent by the depth of the question and my tired brain, which was going on hour three of teaching. When the student saw my hesitation, they continued: “Like what led to you being a teacher and being here today to teach us English?” I stumbled through some semi-incoherent response about loving reading and writing and enjoying helping students feel empowered in telling their own stories. Even after I thought more about the question later, though, I struggled with how I should answer, not because I didn’t have a reason to teach, but because I was getting stuck on the phrasing of the question. “How did you get where you are” makes it seem like I had made it somewhere, like my position in front of the classroom was some sort of “end result”. I usually feel the opposite: like I am stuck on a constant upward climb, forever chasing a “successful” end (and what would this successful end even look like? Passing comps? Getting published? Defending my dissertation? Getting a job? Tenure?) My student spoke to me as if I was on solid ground when I actually felt like I was one hundred stories up on a tightrope in a hurricane. Needless to say, I spiraled for a bit.

When I looked back at the poem above, I caught myself. Deep breath in. Where I am now is a celebration point in and of itself. It’s okay to feel shaky. No one is an expert to start off with. I’ll try to trust and move forward. A little bit of success, a lot of failure. Slowly, but forward. Deep breath out.

This moment encapsulates a lot of my experience reading Peitho. I learned about the practicalities of mentoring, its theoretical backgrounds, the various shapes it can take. But more importantly, I discovered the way mentoring moves beyond time and space, beyond physicality. When talking to a friend in my cohort the other day, I flippantly said, “Well I guess at this point a good dissertation is a done dissertation.” I knew I hadn’t made this phrase up, and in consulting my notes later I found it listed under Win Horner’s “Winnerisms” in her memorial issue (Myers et al. 126). I suppose mentoring even moves beyond life and death. It can always be found in the pages, the poems, the stories of the past, from scholars in the field who remember what it feels like to be on shaky ground, and care enough to share their guidance.

Complexity (or Messiness? Take Your Pick)

The sheer size of the word cloud above is enough to capture how complex and pluralistic the scholarship of Peitho attempts to be. Even more: before I created Figure 2, I had an even larger visual that I had to cut down by hundreds of words because it was unreadable:

Figure 3: In this image, there is an even bigger circular word cloud with so many small words on the outer edge that they are unreadable. The largest words are the same as in Figure 2.

After reading all of Peitho, though, I’ve learned not to shy away from messiness and complexity the way I might have done previously. I think of the way Jill Swienciki sets up her essay in an attempt not to examine the polarized sides of women’s rhetoric, but to look “into the messiness of the in-between” (3). Or the book review that quotes April Baker-Bell telling instructors who are committed to linguistic justice that they “have to be ready for the messiness that comes with the process” (Hull). Or Lisa Mastrangelo and Lynée Lewis Gaillet noting that one of the main goals in studying history is “to create more complex pictures” (22). Even a term like Gloria Anzaldúa’s nepantla can help to capture the chaos of being in-between many words, moments, and spaces (Oleksiak). In all of these examples and more, messiness, complexity, plurality, and chaos are a tool used by scholars and activists to defy white supremacist cis-heteronormative expectations.

The complexity and messiness found in these pages also frequently urged me as a reader to reconsider what I thought I already knew about a topic. Sometimes this reconsideration came from short sentences that suddenly stopped me in my tracks. For example, when I was reading about the ways that even intentionally selecting documents can become harmful, the line “Assemblage establishes a canon.” stuck out to me (Sullivan & Graban 3). I had always thought that if I chose readings for classes, lists, and citations outside of solely the white cis-male Western “dominant canon”, then I could defy the oppressive tendencies of canonization. This article forced me to reconsider the power and privilege I hold in my ability, intentional or not, to establish my own canon. Now it is at the forefront of my mind as I think about what readings I choose to teach and study, and which scholars I choose to cite.

Other times the reconsideration occurred slowly, usually after a topic appeared over the course of several issues. Silence as rhetoric was one such example. I previously would have only described silence to be sort of like a blank; a space where something or someone is being hidden, repressed, or forgotten. And while this understanding is often still the case, I was surprised to find silence framed in the readings in more active ways. A review of Cheryl Glenn’s Unspoken: A Rhetoric of Silence includes the line, “for too long silence has been read as a passive act when in reality it is significantly expressive” and that it is only undervalued “because of its association with weakness or lack” (5). I also appreciated the way Amy Gerald describes her quest to insert the Grimké sisters into Charleston’s public memory as “fueled” by the silences she found (100). Silence was even framed as a tactic of accountability, as Joshua Barsczewski explores in his work with trans writing research. He says that an intentional silence, “is neither an act of allyship nor is it co-conspiratorial, although it has shades of both…In some circumstances, our silence is harmful. But I would encourage all cis researchers to deeply consider whether they need to speak on trans experiences and to ask themselves why” (Barsczewski). Article after article urged me to reconsider silence, and I see it now with much more complexity, as a site of learning, reflection, change, accountability, and most of all agency.

In a similar strand, many of the pieces on pedagogy made me completely rethink my role and practices as an instructor. I was challenged to see feminist pedagogy as occurring in unexpected places through unexpected methods, like the way sororities have used crafting to teach values and challenge hegemony (Kurtyka). In more traditional classroom spaces, articles like “Anticipating the Unknown: Postpedagogy and Accessibility” asked me to consider the ways that classrooms can perpetuate trauma for certain students and how I as an instructor must learn to anticipate and take seriously the needs of the diverse people that make up my classes (Phillips & Leahy). Even topics that I have already taken courses on in my studies, like community-engaged rhetoric, were bolstered as I further considered concepts like the role of emotions in service learning and how to help students work more ethically with communities (Rohan). As I read through all of the articles, I found myself compiling a list of new assignments and activities to try out that might be more engaging for students (Stuckey; Kates; VanHaitsma & Book). I even found quick adjustments that I can easily add to my classes, like using Rusty Bartels’ introductory questions on the first day, to make students feel more welcomed and safer in their identities. Through all of these takeaways, especially in the many pieces dedicated to bell hooks, I was reminded over and over again that a feminist pedagogy is one in which teaching is an act of love.

I am especially grateful to Stacey Waite’s article “Cultivating the Scavenger: A Queerer Feminist Future for Composition and Rhetoric” which made me feel at home and changed the way I think about storytelling, composition, and queerness. I finished the article feeling a heady sense of empowerment as I frantically jotted down plans as to how I could engage a scavenger methodology – a methodology grounded in messiness and plurality – in my future classes.

Most importantly, as I read, I found my understanding of key terminologies to be challenged. In the CWSHRC’s 25th Anniversary issue, Jessica Enoch and Jenn Fishman discuss the choice to begin the issue with a series of key concept statements that frame, reflect on, and briefly define a few popular terms in the field. As noted by the editors, these key concept statements offer the opportunity for all of us to consider how we are using the terms that pervade our scholarship – terms like coalition, history, inclusion, agency, feminism and language rights, materiality, embodiment, and service – in an attempt to consider what has been said about these concepts and what may still be missing (4). In defining and reflecting on the concepts listed above, I was asked as a reader not to think about any of these ideas as having a single definition, but rather as concepts of plurality and complexity. These reflections also helped me consider how varying definitions originated, how they’ve been applied to past research and theory, and how they can prompt new questions for future scholarship. For example, in the key concept statement on “Inclusion”, Stephanie Kerschbaum reminds readers that inclusion is not only about adding in new voices, but about totally reconceptualizing the methods and theories of a field in order to create a space that is sustainable for more diverse styles, questions, methods, and groups of people (20). In other words, inclusion is not simply the opening of a door; it is a complete remodeling of the inside and outside of the building to make the whole place more inhabitable for more people. This view of inclusion goes beyond how the term is often invoked, especially in university settings. And in reflecting on inclusion, as well as all of the key concepts, I was reminded that complacently using terms can often mask their complexity and prevent us from doing the most difficult, but necessary, work.

Even beyond the key concept statements, though, many of Peitho’s articles challenged my understanding of terminology. My definition of “feminism,” for example, became messier as I read each article. As soon as I’d think I had a solid position pinned down, like for example recognizing the difference between an inclusive feminism and white feminism, something like Stephanie Jones and Gwendolyn Pough’s introduction to their special issue would urge me to reconsider. They write, “If you are a person of color and you want to call out limited agendas masquerading as ‘feminist’ that seem to only take white women’s issues into consideration, don’t call that ‘white feminism.’ Call it racism, because that is not how feminism works.”

Similarly, I wouldn’t have thought twice about calling myself an “ally” until I read Aja Martinez urging readers who consider themselves allies to genuinely imagine what they would do if they came across someone being beaten and attacked in a hate crime. Could you “jump into this attack and protect this person with your own body?” she asks. And “If you have to think about your answer, then you should also think about what it means” to call yourself an ally. She then argues instead for being an accomplice because “whereas allies are viewed as those who identify as helpers to the oppressed, accomplices are those who will bear the risk of consequences” (231).

These are, of course, only a few of the many ways this journal asks readers to embrace complexity and challenge their previous knowledge. Many of the questions asked in these articles sat with me for days and linger with me even now. Most of them do not have an easy or singular answer. Instead, these pages are littered with contradiction and tension and conflict, and the writers intentionally refuse to resolve it. As I look again at the vastness of the word cloud, I am reminded of how Peitho asks readers to see many things all at once, not in an attempt to overwhelm, but to better reflect the messy world around us and the bodies we reside in.

Embodiment

One of the most used terms throughout the articles is embodiment, and reading Peitho is, above all else, a bodily experience.

The first line of the key concept statement on Embodiment is “To think about rhetoric, we must think about bodies” (Johnson et al. 39). Our bodies are not something just affected by rhetoric; they do rhetoric. And this “doing” informs our ways of knowing and thus changes the way we read, research, write, teach, and love (39). In my reading, I learned about so many bodies: bodies that moved, danced, fought, changed, loved, transitioned. Bodies holding trauma and bodies filled with joy. Ancient bodies and future bodies. Bodies that crossed borders and time periods. As shown in the word clouds, a lot of the largest words reflect aspects of embodiment. “Race” and “gender” are two of the largest with “queer” and “transgender rhetorics” slightly smaller. Words like “motherhood,” “transnational,” “disability,” “health,” and “religion” appear towards the top, too, all of which have some sort of relation to an individual’s identities, and the way they and their bodies make sense of the world around them. With “intersectionality” being so large in the visual, it also seems to be a goal of many of these works to examine the complexity of the human body, the plurality of it, with all of its identities coalescing together.

Of course, not every body has been represented in the journal to the same degree. As GPat Patterson notes in the introduction to the special issue on Transgender Rhetorics, the fact that the first special issue in the field of Rhetoric and Composition on this topic did not appear until the summer of 2020 is telling. These bodies and others, especially black bodies, are also disproportionately represented in regard to their traumas and do not occupy the same space as their privileged counterparts. And while the journal attempts to move outside of an able-bodied, white, Western, hetero-cis woman perspective, there is more to be done. Even the Coalition name change from “women” to “feminist” to reflect a more inclusive space, took much longer than I expected it to, not happening until May of 2016.

In addition to reading bodies that appeared in the scholarship and considering which bodies were missing, I tried to let my own body be at the forefront of the experience. I found myself angry, happy, sad, joyous, irritated, scared, exhausted, comforted, and seen while reading. While some pieces evoked more emotion than others, the journal as a whole seems to lean into the embodiment it uses as a foundation for its existence.

I cried more than I expected while reading (Every single “in memoriam” got me without fail). I also found myself laughing out loud, something I’ve never done while reading an academic article before. The book review of Wit’s End: Women’s Humor as a Rhetorical and Performative Strategy, ends by saying, “Funny women are much smarter and more powerful than we give them credit for” (120). Peitho gives them credit. I genuinely laughed out loud at Harriet Malinowitz’s stories of interacting with Adrienne Rich, Jessica McCaughey’s footnotes in her article on being a student and a mother during the pandemic, and especially the “World Blue Balls Day” infographic created by Ghanaian online activists (Plange). Also, the fact that the word “horndog” even appeared in an academic article really had me laughing for a long time (Howell). This laughter was evident even in the beginning of the Peitho newsletter, when essays detailing the CWSHRC meetings almost always mentioned the humor or jokes they shared in person. In a review of the 1998 meeting, Shannon Wilson writes to the mentors there, “Your leadership, energy, and humor provided, once again, much needed advice, and even more important, the feeling of inclusion…” (3). Similarly, Danielle Mitchell writes, “While I have attended only the past four Coalition sessions, they have, without exception, each provoked laughter, camaraderie, reflection, and perplexity…” (1). I echo these words so many years later.

My bodily experience reading Peitho also went beyond the author’s tone or topic. Sometimes it was the sheer beauty of the words that got me. I remember thinking all day and night about this passage in an issue: “I’m in it for the haul- long or short. I too dread the slow dying, but I shall live out my life to the end. I love this life with all of its joys and sorrows and dying is an integral part of that life” (Horner 137). These words dig their way into my brain; they crawl under my skin. I too often separate in my head creative writing and academic writing, but I think we are at our best when we find ways to combine both. My notes are filled with stolen passages of beautiful words written by the scholars of Peitho:

“I name the University as a shipyard, but maybe it is more of an echo, a reflection from other architects of power like the police and prison industrial system…But in the classroom we learn from theories that dismantle these complexes. The university has bridges of dissonance” (Williams 10).

“I imagine that there are hundreds of us walking around with little pieces of Adrienne implanted in us. And if she doesn’t exist anymore, well, in my view, God doesn’t either, but so far, that hasn’t lessened his effect upon the world.” (Malinowitz 12).

“How much of our reading and writing is haunted by death and the loss of loved ones? How much of our scholarly work is a collaboration over time, with the voices of our mentors shaping us, and the texts and memories they have given us carried with us?” (Faris).

“Let queerness sing. Let queerness come through you like your spirit does. Take up the expanses of your sentences any way that serves your message. Throw away archaic rules about grammar and syntax. Throw away archaic rules about blazers and keeping your legs crossed. Your style is exquisite. Promise you won’t straighten it. If mainstream journals won’t publish your work, publish it yourself, Riot Grrrl style in zine form. Don’t beg unless you’ve negotiated it.” (Livingston).

Timothy Oleksiak calls some of this “academic lyricism,” a term which when I first read it, I excitedly wrote it down and put a big circle around. Along with it, I wrote the following note in reacting to the quotes above:

“Can you believe we have the privilege of reading these words? I’ve dedicated my life to words, think I know them back to front, and they still knock me out.”

Additionally, the word “love” appears 130 times in my notes. Whether it be radical self-love (Osorio), love as pedagogy (Greco, McKinnie, Bock, Craig, Williams et. al), love as method (Restaino), queer love and listening (Pillof), and more, love fills the pages of this journal. And love is not always gentle; it critiques, it demands change, it calls out injustice boldly and angrily. If I have learned anything from Peitho it is not to shy away from the all-encompassing, all-embodied act of love.

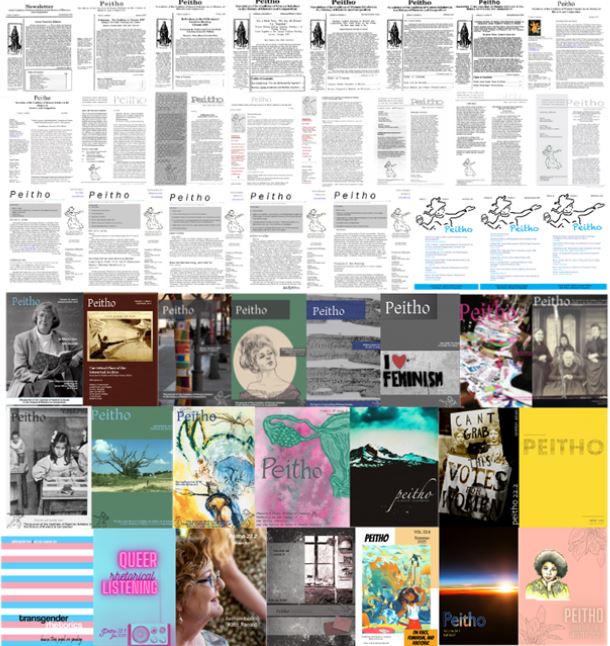

Figure 4: Every cover or first page of Peitho, from 1996 to Winter 2022. Forty-six vertical rectangular screenshots of the Peitho covers in a grid

My experience reading the entirety of the journal was not seamless. There were moments where I about chucked my computer through a window, moments of strife and frustration and disagreement, and moments when I wanted to drop out of academia altogether. Messiness doesn’t always feel like a good thing. At my most frustrated point, I wrote in my notes:

“I guess I thought that hours and hours (and hours) of reading later, I’d feel like I get it. Because if there’s one thing that permeates a graduate school classroom, it’s a desire to get it, to finally feel knowledgeable, like someone worthy of a degree. These [readings] are already so much, but I know that this journal is only a sliver of the scholarship I should read, should know, should cite and work with. I know that for the authors I am reading, their work here is only a glimpse of their work total. How am I to remember it all?? I thought that I’d finally hit a point where I suddenly felt like an expert on a certain topic. Does that ever happen?…It seems like all of my professors and mentors and everyone writing these articles are so smart and accomplished. Do you all feel as though you get it? Do you feel like an expert? Will I ever get to that point? Or should I remain content with feeling like a novice forever and pretending?”

Little did I know that a few pages later I would get to Britt Starr’s piece on white perfectionism in the graduate classroom and I’d reconsider everything I was feeling once again.

In the time I spent reading the journal, a lot of life happened. I finished my second year of graduate school and my fourth-semester teaching. I saw my brother graduate; we celebrated all night at a little piano bar deep in the Midwest. I watched friends get engaged, received two wedding invitations, booked a trip to New York City with friends. I went to two funerals. I helped a good friend pack up and move away from me. I watched the news cover the shootings in Buffalo and Uvalde. I tried to start writing the morning after the latter, but couldn’t find words.

Throughout everything, this scholarship followed along with my little life, the way good scholarship should. Sometimes the writing was so connected to what was happening in my own life that it was as if the article had been written directly for me. Sometimes I got to see how far we’ve come as a field, and sometimes I saw how far we still have to go. In my notes I wrote the following:

“I used to think of academic articles as being annoyingly specific. I’d see the title and think: Who would care about reading something like this? And then I read it, and it feels less like someone is cutting away a sliver of the world to give me a small microscopic bite, and more like I’m seeing an image of human history at large, and this article merely zooms in for a second before zooming right back out again. Or maybe it’s better to think of it like a conversation with friends. Where we all descend into our random stories back-to-back to back until we hardly know what got us on a topic in the first place. But hours have passed, our stomachs hurt from laughing, our eyes are wet with happy and sad tears, and we are all better because of it.”

Call it love or something else, so many of these articles captivated me. At first, I was only going to read articles whose titles jumped out to me as interesting. I’m so glad I decided not to; I would have missed out on so much. Whether I was reading about cookbooks, Parisian salons, Republican Motherhood, the story of Diane Nash, the conflicting narratives of Sojourner Truth’s speech, yarn bombing and craftivism, the first periodical published by and for African American women, the shattering story of Nujood Ali, 19th-century electric girls, failed gender party reveals, or the feisty feminism of Ahed Tamimi, I was hooked. Not every article resonated with me, but so many did. After reading Harriet Malinowitz’s essay, I wrote the following note:

“I was sucked in the whole time reading. It made me smile, it made me sad, it made me want to feel the same way the author feels. I like how much I can see her feel. Reading the article felt like talking to a friend.”

I thought that reading the whole journal would help fill in a lot of the blanks that I’ve carried with me since my first day of graduate school. And while it did answer a lot of questions, I think I leave this process with more blanks than I started with. The good news is that I’m beginning to accept that this is a good thing, that the open spaces are a necessity, a place of potential and growth. I’ve added over 50 books to my reading list through the process of finishing Peitho, so I guess my next journey is to start there. In the meantime, I’ll carry these lessons with me into the future: being a little bit messier, a bit more open to tension, conflict, and contradictions, leading with my body, and remembering that there is a lineage of scholarship to learn from that speaks to who I am and what I have the potential to become.

Works Cited

Barsczewski, Joshua. “Shutting Up: Cis Accountability in Trans Writing Studies Research.” Peitho, vol. 22, no. 4, 2020.

Bartels, Rusty. “Navigating Disclosure in a Critical Trans Pedagogy.” Peitho, vol. 22, no. 4, 2020.

Benson, Kirsten and Fedukovich, Casie. “Mentoring, an incantation.” Peitho, vol. 12, no 1-2, 2010, pp. 8-9.

Bock, Chelsea. “Leading with Love, or a Pedagogy of Getting the Hell Over Myself.” Peitho, vol. 24, no. 2, 2022.

Craig, Sherri. “embracing the erotic.” Peitho, vol. 24, no. 2, 2022.

Enoch, Jessica and Fishman, Jenn. “Editors’ Introduction Looking Forward: The Next 25 Years of Feminist Scholarship in Rhetoric and Composition.” Peitho, vol. 18, no. 1, 2015, pp. 2-10.

Faris, Michael. “For Lisa: A Patchwork Quilt.” Peitho, vol. 24, no. 1, 2021.

Gatta, Oriana. “Connecting Logics: Data Mining and Keyword Visualization as Archival Method/ology.” Peitho, vol. 17, no. 1, 2014, pp 89-103.

Gerald, Amy.“Finding the Grimkés in Charleston: Using Feminist Historiographic and Archival Research Methods to Build Public Memory” Vol. 18, no. 2, 2016, pp. 99-123.

Greco, Sophia. “Embracing a Pedagogy of Love and Grief.” Peitho, vol. 24, no. 2, 2022.

Grohowski, Mariana. “Review: Wit’s End: Women’s Humor as Rhetorical and Performative Strategy.” Peitho, vol. 15, no. 1, 2012, 114-120.

Horner, Winifred. “My Turn.” Peitho, vol. 16, no. 2, 2014, 135-137.

Howell, Tracee. “Manifesto of a Mid-Life White Feminist Or, An Apologia for Embodied Feminism.” Peitho, vol. 23, no. 4, 2021.

Hull, Brittany. “Book Review: Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy by April Baker-Bell.” Peitho, vol. 23, no. 4, 2021.

Johnson, Maureen; Levy, Daisy; Manthey, Katie; and Novotny, Maria. “Embodiment: Embodying Feminist Rhetorics.” Peitho, vol. 18, no. 1, 2015, pp. 39-44

Kates, Susan. “Book Review: Fencing with Words: A History of Writing Instruction at Amherst College during the Era of Theodore Baird by Robin Varnum.” Peitho, vol. 1, no. 1, 1996, pp 3-4.

Kerschbaum, Stephanie. “Key Concept Statements: Inclusion.” Peitho, vol. 18, no. 1, 2015, pp. 19-24.

Kurtyka, Faith. “We’re Creating Ourselves Now: Crafting as Feminist Rhetoric in a Social Sorority,” Peitho, vol. 18, no. 2, 2016, pp. 25-44.

Livingston, Violet.“Excerpts from ‘Terms of Play: Poetics on Consent as Method’.” Peitho, vol. 23, no. 1, 2020.

Malinowitz, Harriet. “The Icon Across the Street.” Peitho, vol. 15, no. 2, 2013, pp. 6-13.

Martinez, Aja. “The Responsibility of Privilege: A Critical Race Counterstory Conversation” Peitho, vol. 21, no. 1, 2018, pp. 212-233.

Mastrangelo, Lisa and Gaillet, Lynée Lewis. “Historical Methodology: Past and ‘Presentism’”? Peitho, vol. 12, no 1-2, 2010, pp. 21-23.

McCaughey, Jessica. “‘This Seismic Life Change’: Graduate Students Parenting and Writing During a Pandemic.” Peitho, vol. 24, no. 2, 2022.

McKinnie, Merredith. “bell hooks Memorial.” Peitho, vol. 24, no. 2, 2022.

Mitchell, Danielle. “Graduate Student Education in Rhetoric and Composition: Who? What? Why?, or, Bow Howdy: We Have Some Work to Do!” Peitho, vol. 4, no. 2, 2000, pp. 1-4.

Myers Madden, Whitney. “Book Review: Unspoken: A Rhetoric of Silence by Cheryl Glenn.” Peitho, vol. 10, no. 1, 2005, pp 5-7.

Myers, Nancy; Hum, Sue; Fleckenstein, Kristie. “Win’s Angels,” Peitho, vol. 16, no. 2, 2014, pp. 125-126.

Nicolas, Melissa. “Intentional Mentoring.” Peitho, vol. 12, no 1-2, 2010, pp. 6-7.

Oleksiak, Timothy. “A Fullness of Feeling: Queer Rhetorical Listening and Emotional Receptivity.”, Peitho, vol. 23, no 1, 2020.

Oleksiak, Timothy. “Queering Rhetorical Listening: An Introduction to a Cluster Conversation.” Peitho, vol. 23, no. 1, 2020.

Osorio, Ruth. “A Community of Beloved Femmes: The Cultivation of Radical Self-Love in Femme Shark Communique #1.” Peitho, vol. 17, no. 2, 2015, pp. 226-248.

Patterson, GPat. “Because Trans People Are Speaking: Notes on Our Field’s First Special Issue on Transgender Rhetorics.” Peitho, vol 22, no. 4, 2020.

Phillips, Stephanie & Leahy, Mark. “Anticipating the Unknown: Postpedagogy and Accessibility,” Peitho, vol 20, no. 1, 2017, pp. 122-143.

Pilloff, Storm Christine. ““Métis and Rhetorically Listening to #BlackLivesMatter.” Peitho, vol. 23, no. 1, 2020.

Plange, Efe Franca. “The Pepper Manual: Towards Situated Non-Western Feminist Rhetorical Practices.” Peitho, vol. 23, no. 4, 2021.

Pough, Gwendolyn and Jones, Stephanie. “On Race, Feminism, and Rhetoric: An Introductory/Manifesto Flow…” Peitho, vol. 23, no. 4, 2021.

Restaino, Jessica. “Surrender as Method: Research, Writing, Rhetoric, Love.” Peitho, vol. 18, no. 1, 2015, pp. 72-95.

Ribero, Ana Milena & Arellano, Sonia C. “Advocating Comadrismo: A Feminist Mentoring Approach for Latinas in Rhetoric and Composition.” Peitho, vol. 21, no. 2, 2019, pp. 334-356.

Rohan, Liz. “Service-Learning at the Northwestern University Settlement, 1930-31, and the Legacy of Jane Addams.” Peitho, vol. 21, no. 1, 2018, pp. 24-42.

Starr, Britt. “Disturbing White Perfectionism in the Graduate Student Habitus.” Peitho, vol. 23, no. 3, 2021.

Stuckey, Zosha. “Ghostwriting for Racial Justice: On Barbara Johns, Dramatizations, and Speechwriting as Historical Fiction.” Peitho, vol. 24, no. 1, 2021.

Sullivan, Patricia and Samra Graban, Tarez. “Digital and Dustfree: A Conversation on the Possibilities of Digital-Only Searching for a Third-Wave Historical Recovery.” Peitho, vol. 13, no. 2, 2010, pp. 2-11.

Swiencicki, Jill. “Rhetoric and Women’s Political Speech in The Lecturess, Or Woman’s Sphere.” Peitho, vol. 5, no 1, 2000, pp. 3-7.

Tucker, Marcy. “Holding Hands and Shaking Hands: Learning to Profit from the Professional Mentor-Mentee Relationship.” Peitho, vol. 12, no 1-2, 2010, pp. 1-5.

VanHaitsma, Pamela and Ceraso, Steph. “‘Making It’ in the Academy through Horizontal Mentoring.” Peitho, vol. 19, no 2, 2017, pp 210-233.

VanHaitsma, Pamela and Book, Cassandra. “Digital Curation as Collaborative Archival Method in Feminist Rhetorics.” Peitho, vol. 21, no. 2, 2019, pp. 505-531.

Waite, Stacey. “Cultivating the Scavenger: A Queerer Feminist Future for Composition and Rhetoric”, Peitho, vol. 18, no 1, 2015, pp. 51-71.

Williams, Kimberly; Scott, La-Toya; Baldwin, Andrea; Gonzalez, Laura. “On Testimony, Bridges, and Rhetoric.” Peitho, vol 23, no. 4, 2021.

Wilson, Shannon L. “Reweaving the Professional Ties that Bind: Teaching, Research, Writing.” Peitho, vol. 3, no. 1, 1999, pp. 1-3.