Solidarity in Feminist Iconography: Gloria Steinem, Dorothy Pitman Hughes, and the Power Fist

Solidarity in Feminist Iconography: Gloria Steinem, Dorothy Pitman Hughes, and the Power Fist

Peitho Volume 25 Issue 4, Summer 2023

Author(s): Rachel Molko

Rachel E. Molko is a first-generation Venezuelan and Jewish feminist scholar-activist. At the time of researching and writing this case study, she was Assistant Director of Northeastern University’s Writing Program. Rachel’s research explores feminist rhetorical theory and feminine visuality in contemporary popular culture. She defended her dissertation in the summer of 2023, presenting on the rhetorical significance of feminist icons, particularly seeking to engage their potentialities for agency and rhetorical citizenship. In the fall of 2023, she joined Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Writing, Rhetoric, and Professional Communication Program. Outside of work, she enjoys watching Jeopardy! with her partner, practicing hot vinyasa, and spending time with her cats.

Abstract: The visuality of solidarity in feminist iconography requires viewers to engage in critical and emotional ways that implicate both subjectivity and social change. By engaging intentionally with feminist icons exhibiting solidarity, viewers-as-critical-consumers participate in their own civic education. This engagement brings together the political consciousness and presence of being that exist in the viewer with the political and social ongoings of society that impact communities. This affective phenomena is where feminist icons may assume rhetorical power by circulating justice-oriented narratives in the public/private sphere of popular culture.

Tags: activism, affect, feminist rhetoric, Icons, photography, popular culture, protest, visual rhetoricIntroduction

Within the literature on solidarity and coalition, there is a tension between those who claim that identity is a central tool for resistance and those who caution that any identity claim engages otherness and exclusion. That latter suggests that as a political tool, identity may be an obstacle to building solidarity in coalition. To bridge this obstacle, icons can operate as cultural mediators by offering a common ground for building connection in “shifting social and political climates” between individuals at distinct intersections of identity (Roberts 83). According to Lauren Berlant, icons within women’s culture[1] can function to create an imagined common ground for viewers of different social, cultural, and economic backgrounds (5). This study draws from Berlant to suggest that feminist icons in an imagined common groundwork by soliciting “belonging via modes of sentimental realism that span fantasy and experience and claim a certain emotional generality among women” (5). In other words, feminist icons may be able to pierce emotional, experiential, and ideological dimensions of culture to build community. Like bell hooks explains in All About Love, what we imagine is vital to what we can accomplish. Writing about the definitions, ideas, and examples of love that we are exposed to throughout our lives, hooks questions what it means to belong and how we can mine cultural discourse to chart our way to our desired destination—such as a more just future. Inspired by hooks, then, I venture to ask, if we imagine it, then isn’t it real? Can this imagined-real space be more than a fantasy? Can this affective discourse become a community resource? From this space, can we create material consequences that further the vision of feminism?

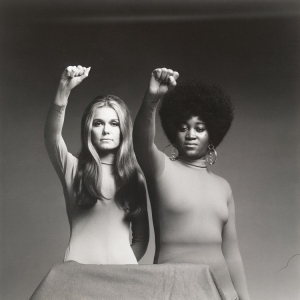

This article presents a case study of the Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes photograph from 1971 by Dan Wynn (referred to in this article as the Wynn photograph) as an icon that has the potential to encourage solidarity, even though it doesn’t represent the vast array of identity formations within the community of feminists. The Wynn photograph carries historical, symbolic, and ongoing significance, capturing an iconic moment in the women’s liberation movement and the broader feminist movement of the 1970s. The black-and-white studio photograph captures the two friends standing side-by-side with their right fists in the air and solemn expressions on their faces. The prominent feminist activists Gloria Steinem and the late Dorothy Pitman Hughes[2] played crucial roles in advancing women’s rights and challenging societal norms. Steinem and Pitman Hughes embody intersectional feminist solidarity, which recognizes that individuals can face multiple forms of discrimination and oppression simultaneously based on their race, gender, class, and other intersecting identities. Specifically, Steinem and Pitman Hughes collaborated and advocated for both gender equality and racial justice and continue to serve as sources of inspiration for those working towards social justice.

Historically, the mainstream feminist movement has struggled with inclusivity and adequately addressing the concerns of people from diverse backgrounds, sometimes being conflated entirely with white feminism. However, the image of Steinem and Pitman Hughes together continues to circulate as a reminder of the importance of diverse voices and the need for inclusive activism. While the photograph is from the 1970s, its themes and messages remain relevant today. The fight for gender equality, racial justice, and intersectional feminism continues, and the photograph can inspire and motivate current and future generations of activists. It reminds viewers of the progress made and the work still to be done in creating a more equitable and inclusive society. Focusing on this image as an icon is necessary because it has not been the focus of rhetorical study in the past; it is memorable and oft recreated; and it has maintained consistent relevance in a mainstream sociopolitical and cultural context (transcending the boundaries of 1970s feminism). In what follows, I offer background on Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes relationship and discuss the significance of rhetorical iconicity. Then, I give a brief overview of the literature on feminist solidarity, often explored through the notion of coalition. I then present three rhetorical moves that the Wynn image, as a feminist icon, makes to communicate solidarity. These moves include emphasizing connection, centering civic responsibility, and circulating visual-emotional resonance.

Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes, 1971

Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes met through Steinem’s journalistic work at New York Magazine in 1969. After an interview for Steinem’s column, the women formed a friendship and became speaking partners at meetings for women’s liberation on college campuses and in communities (Gutterman). Between 1969 and 1973, the women traveled as a team with other Black feminists such as radical feminist lawyer Florynce Kennedy and queer Black feminist and civil rights advocate Margaret Sloan (Baker). After their years on the road, Steinem and Pitman Hughes released the first issue of Ms. magazine in 1972. The magazine became the first national American feminist magazine and is still in print today. A year earlier, in 1971, Steinem and Pitman Hughes posed for the iconic image at the center of this case study. The Wynn photograph first appeared in the October issue of Esquire, an American men’s magazine, emphasizing a call to solidarity between the feminist and civil rights movements. Over time, the photograph has also become a representation of solidarity across different marginalized groups in the feminist movement because it emphasizes the importance of addressing various forms of oppression simultaneously.

Figure 1: Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes, 1971, Dan Wynn.

The photograph itself is visually powerful and conveys a potent message, providing representation for both white and Black women in the feminist movement. The image features Steinem and Pitman Hughes positioned in front of a gray-gradient background. The simplicity of the image is striking, where the lack of excess suggests a desire to eliminate distractions from the message. The color scheme elicits a serious tone, one that is supported by their resolute expressions. The women are centered in the image, side by side, and facing the camera directly. Their gaze suggests a commitment to their message, a shamelessness in confronting the viewers as their audience. Originally, the audience was Esquire magazine’s male viewership, which positions the image as an embodiment of a challenge to the male gaze in a literal sense.

The photograph has traveled far beyond the exclusivity of the niche Esquire magazine and sits in residence at the National Portrait Gallery, a Smithsonian institution, that “present[s] people of remarkable character and achievement” (Bagan). Steinem’s hair is straight and covers her chest, her “money pieces” (the sections of hair growing from the hairline above the forehead) are dyed light blonde—her signature look. Pitman Hughes wears her hair natural with tight coils, styled as an afro. She also wears large hoop earrings. Pitman Hughes’ hair and accessories carry an aesthetic of Black culture and style of the times donned also by iconic entertainer Diana Ross and Black feminist radical professor and activist Angela Davis.[3] Steinem and Pitman Hughes both wear long-sleeve turtlenecks in a neutral color. In front of them is neutral-colored draped fabric meant to resemble a skirt. Both women are holding their right fists clenched in the air above their heads and in front of their face, a gesture referred to as the raised fist.

Rhetorical Iconicity

Before analyzing the image, it is important to discuss the rhetorical significance of feminist iconography. Feminist iconography requires viewers to engage in critical and emotional ways that implicate both subjectivity and social change. As Lauren Berlant implies, imagined common ground is often circulated through aesthetic and emotional narratives found in books, personal testimony, essays, films, television, and other visual genres such as icons. Herein lies the rhetorical significance of icons for feminist solidarity. By engaging intentionally with feminist icons exhibiting solidarity, viewers-as-critical-consumers participate in their own civic education. This engagement brings together the political consciousness and presence of being that exist in the viewer with the political and social ongoings of society that impact communities. Popular culture narratives create and circulate a specific set of expectations that inform the role individuals assume in given interactions, dynamics, and relationships. With these narratives come icons that reference the values and outcomes of the narratives. While these narratives begin to inform an audience’s worldview, they also create community by binding members to the same promises—or the same enemy. This affective phenomena is where feminist icons may assume rhetorical power by circulating justice-oriented narratives in the public/private sphere of popular culture.

For example, “Barbie” (the idea, doll, and franchise) has been recently reintegrated into the public imagination as a feminist icon through Greta Gerwig’s critically acclaimed box-office hit film of the same name. As a doll, Barbie invokes a continually shifting narrative of women’s place in society. At first, she was introduced as an alternative role-playing toy to the common “baby doll.” The Barbie doll invited children to imagine themselves as adults with jobs and interests outside of child-rearing. While Barbie’s iconographic narrative begins by shifting public discourse on women’s domesticity to women’s career diversity and self-expression, Barbie has also been complicit in the unrealistic beauty standards and sexualization imposed on women. Yet, in 2023, Greta Gerwig reintroduces Barbie; living in “Barbieland” means that everyone has a role to play, women make the important decisions without being in competition with each other, and men function as supportive accessories. The new Barbie fantasy may be a caricature of a feminist future, but it attempts to deal with the consequences of hegemony in politics, personal development, and relationships. The film has made feminist ideals a mainstream topic of conversation in the pinkest and most hyper-feminine way possible–without trivializing them. The film seeks to offer a reimagined-real affective space through and for feminist visual culture–and it carries its power through rhetorical iconicity.

Thus, the idea is not for trickle-down empowerment from icons, but for icons to generate conversation over the varying relationships to the images, values, and personas that they offer. Icons, as discursive articulations, allow individuals to imagine their positioning in the world. In On Racial Icons, Nicole Fleetwood contends that racial icons can function as “a counterbalance to intentionally demeaning characterization[s of Black Americans]” and that “racial icons can serve to uplift, literally and symbolically, ‘the black race’ and the nation” (4). While she is speaking specifically in the context of the national Black community, I forward that the simulation of solidarity inherent in engagement with icons is a place from which to draw a morsel of empowerment through feminist narratives as well—connecting through affinity and shared goals. Fleetwood suggests that “these images can impact us with such emotional force that we are compelled: to do, to feel, to see” (4). This process, albeit in reverse, mediated consciousness-raising manifests in the 21st-century through popular culture discourse. Interacting with visually-represented solidarity in feminist iconography through sight simulates emotional connection of differently-experienced (yet shared) narratives among non-men in patriarchy, all with the hope that the connection is strong enough to bring us together in action.

I recognize that this process is an appropriation of an externally provided image and the role that accompanies it. But if this phenomenon is already taking place, let us analyze the apparatus by which this kind of interpellation is imposed. Judith Lakämper suggests that the basis for solidarity is not the “affective attachment to a shared fantasy” but “from an investment in the conversation with others who struggle in similar, yet also different, ways with the genres they encounter” (134; 132). Despite the advancements in women’s rights, the changing landscape of media, and the mainstreaming of feminist discourse, communities continue to organize around images from a shared feminist history. The Wynn photograph has endured as a featured visual of feminist activism for over fifty years in various forms including posters at protests, images in social media posts, alluded to in reenacted photographs by people of all ages, races, and backgrounds, and more. In this case study, I argue that the image exhibits solidarity through three rhetorical moves: emphasizing connection between differently positioned women in political discourse, centering civic responsibility to respond to social injustice, and projecting visual-emotional resonance that transcends generations.

Solidarity and Feminism

I define solidarity as a sense of shared responsibility for the wellbeing of others. Often, a problem arises when theorizing the relationship between individual and community in a politics of equity and change. On the one hand, feminism underscores subjectivity, a perspective coming from a specific body, history, and status, as a place from which to draw knowledge. On the other hand, feminism values systemic change, the fundamental reform of social protocol and procedures that exceed individual circumstances of oppression. These foci, subjectivity and social change, engage a duality of feminism, one which requires attention to the individual as well as the community in achieving feminist goals. Solidarity brings these foci together in considering the self in relation to others in the pursuit of shared goals. More specifically, this study posits that the visuality of solidarity in feminist iconography requires views to engage in critical and emotional ways that implicate both subjectivity and social change.

A particularly feminist solidarity refers to a coalitional response to inequitable treatment of minoritized people and communities. Alice Wickstrom et al. suggest that solidarity “emerges from the capacity to affect and be affected, through care, compassion, and empathy with and for others” with the goal of “social transformations that are made possible through ‘democratic engagement’” (857). The hinge here is that solidarity is care with a purpose carried out through affective and political encounters of care and advocacy. I’m interested in framing solidarity as an embodied practice rather than a democratic engagement. The affordance here is to be able to emphasize the bodily, and otherwise material, elements of solidarity. Coming from a new materialist perspective, Wickstrom et al. acknowledge that while “discursive assemblages between different bodies” are not inherently aligned, that the “embodied struggles support the emergence of solidarity” through a shared sense of vulnerability, public affirmation, and symbolic resources. In other words, the source and manifestation of oppression, and the language used to identify it, might not be universal. However, willingness to share, responsiveness and recognition, and common references—such as popular culture icons—allow feminists to enact solidarity. In the case of this study, Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes’ friendship and political partnership offers a prolific example of the power of unity in the face of difference.

While feminist solidarity can be founded on personal meaning attached to experience and the commonalities thereof, the presence of power imbalances, ideological differences, and the impact of historical relationships to power and privilege should not be ignored. For example, Linda Berg and Maria Carbin illustrate the damaging effects of “we” rhetorics under the guise of feminist solidarity. After an attack on a Muslim woman in Sweden, Muslim feminist activists started #HijabUppropet (#HijabOutcry), a call for Swedish feminists to post selfies wearing hijab. Berg and Carbin illustrate how the well-intentioned participation of non-Muslim Swedish women risked “reinstalling the white citizen as the self-evident subject of feminist solidarity” through cultural appropriation (134). The visuality of white women in hijab obscures the racist motives that prompt violent attacks. Rather than condemning racism, prejudice, and hatred, the campaign turned into a conversation about the right for all women to choose to cover. The study illustrates 1) that there are still barriers for women of color to function as agents of feminist solidarity as well as 2) the stumbling blocks in the visual enactment of solidarity.

In the case of the Wynn photograph, similar imbalances became apparent in the rhetorical life of the image. While the women are featured in the photograph in equal measure, the Esquire article that first accompanied the image framed their activism solely in the context of Steinem’s contributions to the women’s movement. In the years to follow, Steinem’s fame and public intrigue overshadowed Pitman Hughes, and other non-white activists, in mainstream coverage of feminist activism. In fact, Gloria Steinem has been referred to as “the world’s most famous feminist” despite her consistently collaborative engagement with feminist activism suggesting that she rarely acts alone (Karbo). In any case, the visual harmony represented in the image does not necessarily mirror the public perception of the figures in the photograph, but that doesn’t change the complementary nature of their friendship and the work they were able to accomplish together.

Clearly, any attempt to describe membership or belonging also implies a boundary, indicating which groups or individuals are different or “other.” Thus, within the literature on solidarity and identity, there is a tension between schools of thought. On one hand, there are those who claim that identity is a central tool for resistance. On the other hand, there are those who caution that identity is an obstacle to solidarity rather than a tool because any identity claim has the consequence of imposing otherness and exclusion. A solution to this tension might be to encourage an active construction of identity rather than assuming identity from fixed categories. Similarly, Elizabeth R. Cole and Zakiya T. Luna discuss how feminists reconceptualize identity as an articulation of how their bodies are controlled by the state, rather than any inherent association with their embodied identity. Their study illustrates how feminists who occupy subordinated identities have developed a complex understanding of the ways that identities are crafted through lived experience, rather than through phenotypic commonalities as sole points of connection.

However, active constructions of identity may not account for the imposition of others’ perspectives of that identity. Agnes Varda speaks to this imposition, citing the power of seeing and looking in reclaiming one’s subjectivity. In an interview documented in the film Filming Desire, Varda states, “The first feminist gesture is to say: ‘OK, they’re looking at me. But I’m looking at them.’ The act of deciding to look, of deciding that the world is not defined by how people see me, but how I see them” (Mandy). Her assertion underscores the rhetorical significance of paying attention and looking. The starting point for a feminist praxis, according to Varda, is to look, to pay attention, to see from where we stand, to critically consume the world around us, and to construct our worldview from meaning that resonates with our experience. In a sense, Varda asks us to make peace with being seen and to ground ourselves in the power of looking back. Thus, this project brings a feminist rhetorical perspective to the potentialities of viewer engagement with textual, visual, and material properties of icons that may significantly, but often implicitly, affect citizens’ understanding of their own role in the community.

Solidarity in Feminist Iconography

Earlier in the essay, I describe the image from the National Portrait Gallery that hosts the image in its entirety (shown in Figure 1). While it is important to consider the background and context of this image as part of the rhetorical situation within a case study, it is also important to recognize that the context in which the photograph is encountered is oftentimes absent of the photograph’s origin story and historical significance—a typical occurrence in the rhetorical life of icons. As the visual dimension of images exists in a constant present, remaining unchanged by and untethered to the passing of time, ideology embedded in the image is often detached from specific context when the image stands alone—or the image may take on the context of other rhetorical situations through circulation. For this reason, I analyze the image as an image, observe the visual and rhetorical presence of solidarity, and draw from Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites to pull visual and contextual significance from the image and its history. In doing so, my goal is to illustrate the resonance of solidarity in feminist iconography.

Emphasizing Connection

Minimizing differences maximizes unity in the context of this photograph. The nature of iconic imagery lies largely in its ability to reproduce ideology. Especially evident in the Wynn photograph is a visual phenomenon of icons which “presents asymmetrical relationships as if they were mutually beneficial” (Hariman and Lucaites 9). The racial incongruity between Steinem and Pitman Hughes has been a source of skepticism and, at times, a dismissal of their call to solidarity. However, the composition of the image and the congruity of their styling suggests that both figures are equally important in the frame[work] of their efforts. This marked phenomenon of iconicity suggests that the image “presents a social order as if it were a natural order” (9). Without containing any reference to the contrary, the image omits any notion of misalignment between the figures. In this sense, the image begins from a place of sameness or similarity to emphasize the call to solidarity. The color palette, the framing, and the sameness in stance, gesture, expression, and dress bring the women together in their call to solidarity.

The intentionality of the image in its totality mirrors the intentionality of Steinem and Pitman Hughes activism in a number of ways. First, filtering the image in black-and-white eliminates a stark contrast in skin pigment without obscuring that the women come from different racial backgrounds. This choice is important because ignoring difference can result in erasure of differently experienced forces of oppression, a pitfall that contemporary feminism is wont to avoid. However, the filter creates a uniform color palette that allows for an overall harmonious visual. Second, no woman is centered in the image. This choice allows for both women to take up as much space as their bodies require without framing any individual as the “subject” or “star” of the image. According to Hariman and Lucaites, “photography is grounded in phenomenological devices crucial to establishing the performative experience” (31). In other words, the camera shapes the viewer’s perception and actively involves viewers in constructing meaning, leading to a performative experience where they engage with the photograph on a subjective level. The framing, or boundaries of the photograph, marks the work as a special selection of reality that, in this case, is situated in feminist and civil rights activism of the 1960s and 1970s. Thus, the framing of the image allows that they are both expressing the message of solidarity and action in the image. Had either woman been in the foreground of the image, the message of solidarity would have been associated more so with the foregrounded person. Similarly to the lack of centering, had only one person been making the gesture, the call to solidarity would have been associated with only one person or one cause—and may not have been as compelling.

Third, the fashion in the image strives to create the sense of togetherness. This is where the power of clothing and the composure of dress is utilized. The turtlenecks offer a streamlined, dramatic, and striking silhouette that aligns with the urgency of their call to solidarity. During the 1970s, during which Steinem and Pitman Hughes worked together through their activism, turtlenecks were fashionable for other activism and advocacy groups. For example, Black Panthers and their supporters often wore black turtlenecks. While sporting a different color, the choice in dress for the Wynn image brings together the origins of the raised fist gesture in the fight for racial equality with the feminist aim of securing women’s rights. The clothes bring the women together visually as one, most notably in the choice to stand together behind the abstract skirt. The sharing of a skirt suggests that the women are presenting a united front as women, for the skirt in 1970s mainstream America was seen as a predominantly female style. Thus, the photograph speaks to women supporting women in the face of injustice, while demanding audience involvement in, or at least awareness of, the cause.

Centering Civic Responsibility

The women are united in solidarity most overtly through the raised fist gesture, a gesture laden with a message of equality and namely civil rights. When the photograph was taken, the raised fist was also referred to as the Black power salute. Thus, the Wynn image is an interesting space to think about communicating social knowledge. In No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy, Hariman and Lucaites[4] say that an iconic photograph “must activate deep structures of belief that guide social interaction and civic judgment and then apply them to the particulate case” (10). Undoubtedly, the image communicates social knowledge through its historical and cultural significance, but it also contradicts hegemonic ideologies sex and race. Namely, the image communicates the civic responsibility to advocate for and prioritize human rights, racial and gendered. However, this social knowledge does not necessarily come from “deep structures of belief that guide social interaction and civic judgment.” The social knowledge in the image contradicts deep structures that guide belief because the dominant ideology at the time of the image’s creation did not align with the political aims for which Steinem and Pitman Hughes were advocating. Hariman and Lucaites write that iconic images are born in conflict or confusion (36). The raised fist might not have become a powerful symbol if equality and civil rights were already embedded in society’s deep structures of belief. The kind of social knowledge in the iconic image comes from critical thinking, awareness, and a compulsion to move toward more just social practices.

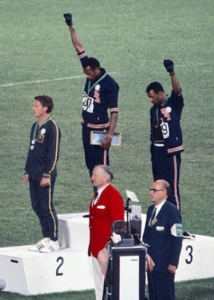

Thus, the exigence of the image is to contradict the status quo through solidarity. However, looking at the image from a contemporary standpoint, the raised fist is more likely seen as a symbol of solidarity and pride specific to the Black community. The Wynn image itself follows another iconic moment that took place at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. During the medal ceremony for the track event, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two Black male Olympic sprinters, held their fists in the air with heads bowed for the entirety of the American national anthem (shown in Figure 2). The gesture was embodied to honor the Black community in America, but also to draw attention to the Olympic Project for Human Rights at San Jose State University, addressing the continued prejudice imposed on Black America. It is worth noting that their demonstration involved more than the raised fist gesture, but other material and symbolic references to racial and social injustice in the United States on a notably apolitical international stage.[5] However, what these historical moments share are the centering of Black activism on the world stage, the signification of solidarity in community, and a demonstration by a pair of activists.

Figure 2: Photograph of Tommie Smith and John Carlos standing on the Olympic podium, shot in 1968 (Zirin).

There is similar, albeit astonishingly unequal, negative feedback in the reception of the Olympians’ and the feminists’ political gesture. In Smith and Carlos’ case, they received a lifetime Olympic ban and Smith lost his NFL offer, among other unjust consequences[6] (Marinelli 446). In Steinem and Pitman Hughes’ case, the Esquire article framed their activism solely in the context of Steinem’s contributions to the women’s movement, all the while calling Steinem’s character into question. In the accompanying article titled “She: The Awesome Power of Gloria Steinem,” Leonard Levitt assessed that Steinem was “good at manipulating the very rich and the very famous” and described her writing as “pedestrian” (87, 202). As evidenced by the title, he dramatically obscured the presence and relevance of Pitman Hughes all the while publishing disparaging commentary on Steinem. Additionally, Levitt ignored the presence of the raised fist gesture in the image, which could reveal a causality between the efficacy of the raised fist and the bodies that wield it. For two black bodies upholding the gesture received condemnation on an international level, while the visuality of resistance from an interracial female pair is at first dismissed and, later, exalted as a beacon of feminist hope, history, and solidarity.[7]

There are key differences in the images, to be sure, including the rhetorical situation of each image, the posture and stance of the subjects, and the way they are dressed. The image of Steinem and Pitman Hughes was less extemporaneous in that it was planned for, staged, and studio quality, serving as visual accompaniment to an article about Steinem’s activism for liberation. Not to mention that the visualization of women’s bodies in a men’s magazine drew a different kind of attention to the gesture of solidarity—one that had the consequence of undermining the significance of social justice activism and feminism in general. As alluded to earlier, Steinem and Pitman Hughes appropriate a demonstration of racial power as a demonstration of women’s/feminist activism. This gesture embodies a contemporary intersectional feminist rhetoric of solidarity by inserting a visual marker that counters the idea of white feminism. With the origins of the raised fist located squarely in Black counter politics, the fist interrupts a reading of the article that takes-for-granted Steinem’s whiteness and beauty as the central draws of her image as a public figure. While the performative stance between the Olympic moment and the Esquire photo are similar, the difference in response and ultimately in rhetorical effect can be traced to the bodies “speaking” and the rhetorical situations in which those bodies exist.

Circulating Visual-Emotional Resonance

Because the outcomes of justice and solidarity discourse are deeply tied to the material conditions of women, people of color, and marginalized communities, there is an element of emotionality that the image evokes. Physical bodies center the humanity of feminist activism in a way that text and caricature do not. Hariman and Lucaites write that the performance trafficked by bodies evokes emotional responses when the expressive body is placed in the social space of the photograph. The social space of the photograph refers to the social nature in which photographs are shot and experienced, creating a network between the photographer, the camera, the figures in the image, and the viewer. In the case of the Wynn photograph, the image deals with deeply personal and socially significant issues related to gender equality, identity, and power dynamics—all of which are relevant to ourselves and our loved ones in one way or another. Combining the social and psychological attachment to these issues with our attachment to our desire for personal and communal well-being is going to bring about an emotional response. These emotional responses form a powerful basis for solidarity and action through the rhetorical situation of icons as still imagery (36).

Alongside the subject matter, the apparatus of the image is involved in an interactive dynamic with the viewer that involves emotional resonance. Hariman and Lucaites explain that one observes social interaction depicted within the frame and by doing so, those in the frame are put into a social relationship with the viewer (36). Steinem and Pitman Hughes, purposefully or not, are utilizing this feature of photography to speak directly to the viewer and bring them into a conversation about change. Particularly, it is important for iconic imagery to situate a message within a particular scene and specific moral context, both of which the Wynn image exemplifies as a visual artifact of justice activism and feminism, more specifically. The clear message embedded in the image, and the emotional resonance associated with humanitarian work, has allowed the image to evolve as “a technique for visual persuasion” in specific rights-related political discourse (Hariman and Lucaites 12). Because it is easily referenced, reproduced, and altered, the image offers a means to tap into the power of circulation and the rich intertext of iconic allusiveness for rhetorical effect through its persuasive emotional efficacy.

Notably, the image is present at high points of contemporary feminist activism such as the Women’s March of 2016, the rally against the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police in 2020 (shown in Figure 3), and the Pro-Choice protests of 2022. Not only do the messages in the photograph clearly resonate, but there are layers of historical significance that bring the image into context with leading feminist concerns of today such as antiracism and justice, women’s rights, and representation. According to Hariman and Lucaites, iconic photographs are “accessible and centrally positioned…images for exploring how political action and inaction can be constituted and controlled through visual media that tap into public memory” (5, 6). The continued presence of the image within feminist organizing as well as the digital sphere suggests that it is influential in shaping collective memory as well as providing figural resources for communicative action. The emotional impact of the Wynn photograph lies in its representation of unity, empowerment, intersectionality, historical significance, and the ongoing fight for equality. It encapsulates the spirit of activism and the deeply felt emotions that come with advocating for social change. Not only does the emotional resonance of the image come from its association with the progress Steinem and Pitman Hughes helped achieve, but the emotions conveyed in the image are timeless and continue to resonate with people today. The struggle for gender and racial equality is ongoing, making the image relevant and emotionally charged in contemporary contexts. All the while, its reproduction and reenactment evidences the impactful and resonating rhetoric of feminist iconicity.

Figure 3: Photograph of person holding the Wynn image on a protest sign at a rally against the killing of George Floyd, 2020, Kevin Mazur.

The image’s role as a tap into the public memory has allowed for its capacity to influence to increase over time. To learn where the image has gone and how it has served feminists, I took to the internet.[8] I was able to trace a plethora of hits that feature the image, including but not limited to: Articles, message boards, social media posts, timelines, captions, art, retail pages, blogs, listicles, press releases, film reviews, event pages, college websites, fundraisers, podcasts, interviews, women’s march posters, and online exhibits. The most striking outcome of my search was not that the image has lived in all of the aforementioned rhetorical situations, but that it had been reenacted over the years by all different kinds of people. The specificity of the image creates opportunities for reproductions, demonstrating how aesthetic familiarity factors into iconic efficacy. In fact, the three elements outlined earlier (color palette; framing; shared stance, gesture, expression, and dress) have continued to be present in replications. Aesthetic familiarity stems from “the realm of everyday experience and common sense” that creates a “moment of visual eloquence” (Hariman and Lucaites 30). This again draws heavily from the embodiment of the call to solidarity in the raised fist but also through the visuality of the female body in the simple and visually uncomplicated composition of the photograph.

Figure 4: Photograph of two young girls reenacting the Wynn image, 2021, Shauna Upp Pellegrini.

As demonstrated by the photograph of the young girls recreating the image (Figure 4), icons interpolate a form of citizenship that can be imitated. In “Rhetorical Citizenship: Studying the Discursive Crafting and Enactment of Citizenship,” Christian Kock and Lisa S. Villadsen write that the “notion of rhetorical citizenship offers a frame for studying very diverse discursive and other symbolic formations to see how they may either contribute to or alter common conceptions and practices relating to societal identity and cohesion” (582). Icons, as discursive and symbolic formations, can define relationships between civic actors by functioning as a mode of civic performance (Hariman and Lucaites 12, 30). In the case of Wynn photograph, the image offers a civic through an enactment of feminist values of friendship, solidarity, and activism. Both women exude a sense of empowerment and confidence in the image. Their raised fists and assertive gestures convey the idea that they are standing up against inequality and injustice, emphasizing the importance of self-empowerment in the fight for equality.

By posing with their bodies in a confrontational stance, holding a politically charged gesture, Steinem and Pitman Hughes demonstrate that they are women with power to advocate for their stake in the political discourse. While they contradict the dominant ideology in capitalist patriarchy, they are defining an oppositional relationship to the state—and the opportunity to catalyze dissent is powerful for feminist theorizing on a large scale. Viewers who feel represented by the icon are realized not as individuals, but as feminists, dissenters, citizens, or other politically implicated interpellations. However, because representation is always incapable of reproducing the social totality, any political discourse or image necessarily fails to meet all needs while it cannot avoid signifying biases, exclusions, and denials (37). The image itself is not a perfect model or representation of solidarity, equality, womanhood, or anything else, but it offers a visual touchstone in an often abstract political discourse.

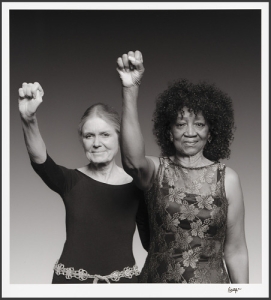

Figure 5: Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes, 2013, Dan Bagan.

In 2013, Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes reenacted the Wynn photograph themselves at a birthday party and fundraiser organized by Pitman Hughes. According to Dan Bagan, the photographer of the 2013 photograph (Figure 5), someone from the crowd “of hundreds” called out for the women “to do the salute” (Hampton). Referring, of course, to the raised first that is part of their visual legacy as friends and activists. Reenacting a photograph can be a way to commemorate a significant moment in history and reflect on the progress made since then. It allows individuals to revisit their past activism and the impact it has had on the feminist movement and society as a whole. By reenacting their photograph, Steinem and Pitman Hughes reflect the continued relevance of their message and ideals, reminding audiences of the ongoing struggle for gender equality and social justice and emphasizing that the issues they fought for are still pertinent today. Reenactments of iconic images can generate conversations, raise awareness, and reinvigorate public interest in specific issues. By revisiting the photograph and sharing the reenactment, Steinem and Pitman Hughes can reignite discussions on feminism, gender equality, and social justice, prompting a renewed focus on these topics.

Limitations

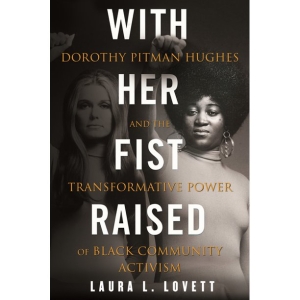

While Gloria Steinem’s national media presence only grew, Dorothy Pitman Hughes continued to prioritize community activism. Some of her endeavors involved grassroots organizing in Harlem, advocating for Black-owned businesses, and urging the importance of childcare and welfare as tenets of the women’s movement. The only biography written about Pitman Hughes features the iconic raised fist photograph as the cover image. Titled With Her Fist Raised: Dorothy Pitman Hughes and the Transformative Power of Black Community Activism and written by Laura L. Lovett, the book was published in 2021 (Figure 6). Pitman Hughes shares the cover of her own biography with Steinem. Although Steinem’s image appears faded, leaving Pitman Hughes a highlighted figure. This choice begs several questions. Does Pitman Hughes only bear recognition for her proximity to Steinem? Is the image a way for the publishers to profit from Steinem’s commodified image? Did the publishers think the biography wouldn’t sell without centering the friendship between Steinem and Pitman Hughes? There was certainly an effort to emphasize Pitman Hughes as the “main character” in the image, so why include Steinem at all? Predictably, the culprit here would be racial capitalism, but also white-heteronormative standards of beauty that are universalized in America, and the centrality of white women in the women’s movement.

Figure 6: Image of the book cover of With Her Fist Raised: Dorothy Pitman Hughes and the Transformative Power of Black Community Activism by Laura L. Lovett, 2021.

While the media’s fascination with Steinem brought attention to the causes she championed, it also served to erase the presence of the other valuable leaders of the Women’s Movement such as Pitman Hughes. Pitman Hughes’ made enduring contributions to feminism, civil rights, and humanitarian welfare, becoming a noted community activist when she began raising money for imprisoned civil rights protesters in the 1960s. Raising three daughters, she took it upon herself to address a lack of childcare services in her neighborhood. In 1966, she founded the West 80th Street Community Child Day Care Center in Manhattan, charging a tuition fee of five dollars per child per week, regardless of income bracket. The day care center became a community resource that offered professionalization opportunities and housing assistance. These efforts are in line with Pitman Hughes’ foundation for her feminism, which stems from the need for safety, food, shelter, and childcare, health and safety issues that white feminism has often failed to take up holistically and inclusively.

Conclusion

In this study, I analyzed the rhetorical significance of solidarity in feminist iconic imagery through Dan Wynn’s 1971 photograph of Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes. In doing so, I presented three rhetorical moves that the Wynn photograph makes as a feminist icon to communicate solidarity: emphasizing connection between differently positioned women in political discourse, centering civic responsibility to respond to social injustice, and projecting visual-emotional resonance that has endured as a featured visual of feminist activism for over fifty years. Steinem and Hughes were not only collaborators but also friends. The genuine camaraderie between them is evident in the image, reflecting the emotional support that can be found in alliances formed through shared ideals. The image has become an inspirational symbol for feminists and activists who seek to challenge systemic inequalities. It reminds individuals of the power of solidarity and the importance of standing up for justice. The photograph was taken during a period of significant social and political change, when the women’s liberation movement and the civil rights movement were intersecting.

Serving as a visual representation of the changing landscape of feminism, the photograph’s continued relevance to feminist causes of today also serves as a reminder that there is more work to be done. By revisiting feminist iconography as rhetorical scholars, we can continue the work of interrogating the imbrication of racial capitalism in popular culture. A few ways we might take up this challenge would be to examine how capitalist systems co-opt feminist ideals for profit while perpetuating inequality and exploitation; how media portrays women and their agency in relation to consumerism, work, and activism; and how marginalized communities use these icons to challenge racial capitalism and demand justice. This approach can help shed light on the ways in which systems of oppression operate so as to empower individuals and communities to resist and demand change.

Works Cited

Bagan, Dan. “Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes.” National Portrait Gallery, 2013, https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.2017.105.

Baker, Carrie N. “The Story of Iconic Feminist Dorothy Pitman Hughes: ‘With Her Fist Raised.’” Ms. Magazine, The Feminist Majority Foundation, 23 Sept 2021, https://msmagazine.com/2021/09/09/dorothy-pitman-hughes-feminist-gloria-steinem-who-founded-ms-magazine/.

Berg, Linda, and Maria Carbin. “Troubling Solidarity: Anti-Racist Feminist Protest in a Digitalized Time.” Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 3 & 4, 2018, pp. 120–36, https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.2018.0035.

Berlant, Lauren. The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008, p. 5.

Cole, Elizabeth R., and Zakiya T. Luna. “Making Coalitions Work: Solidarity Across Difference Within US Feminism.” Feminist Studies, vol. 36, no. 1, 2010, pp. 71–98.

Fleetwood, Nicole. On Racial Icons. Rutgers University Press, 2015.

Gutterman, Annabel. “Beyond Gloria Steinem: What to Know About the Women of Color Who Were Instrumental to the Women’s Liberation Movement.” Time Magazine, 30 Sept 2020, https://time.com/5894877/glorias-movie-activists/.

Hampton, Laura. “Smithsonian Claims Local Photographer’s Remake of Iconic Photo.” The St. Augustine Record, 2017 17 Oct., https://www.staugustine.com/story/lifestyle/2017/10/17/smithsonian-claims-local-photographer-s-remake-iconic-photo/16290962007/.

Hariman, Robert., and Lucaites, John Louis. No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

hooks, bell. All About Love. William Morrow Paperbacks, 2018.

Karbo, Karen. “How Gloria Steinem Became the ‘World’s Most Famous Feminist’.” National Geographic, 25 March, 2019, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/how-gloria-steinem-became-worlds-most-famous-feminist

Kock, Christian, and Villadsen, Lisa S. “Rhetorical Citizenship: Studying the Discursive Crafting and Enactment of Citizenship.” Citizenship Studies, vol. 21, no. 5, 2017, pp. 570–586.

Lakämper, Judith. “Affective Dissonance, Neoliberal Postfeminism and the Foreclosure of Solidarity.” Feminist Theory, vol. 18, no. 2, 2017, pp. 119–35, https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700117700041.

Levitt, Leonard. “She: The Awesome Power of Gloria Steinem.” Esquire, 1 Oct 1971, https://classic.esquire.com/article/1971/10/1/she.

Lovett, Laura L. “With Her Fist Raised: Dorothy Pitman Hughes and the Transformative Power of Black Community Activism.” Beacon Press, 2021.

Mandy, Marie, director. Filming Desire: A Journey Through Women’s Film. France, 2000, https://www.wmm.com/catalog/film/filming-desire/.

Marinelli, Kevin. “Placing Second: Empathic Unsettlement as a Vehicle of Consubstantiality at the Silent Gesture statue of Tommie Smith and John Carlos.” Memory Studies, vol. 10,4, 2017, pp. 440–458.

Mazur, Kevin. “Protests Against Police Brutality Over Death Of George Floyd Continue In NYC.” Getty Images, 2020, https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/protester-holds-a-poster-that-shows-an-image-of-gloria-news-photo/1233491951?adppopup=true.

Noveck, Jocelyn. “Pioneering Black Feminist Dorothy Pitman Hughes Dies at 84.” FOX 5 Atlanta, FOX 5 Atlanta, 11 Dec. 2022, https://apnews.com/article/new-york-city-gloria-steinem-d5c11ee749bfc94f4834622b28b2bcc4.

Roberts, Chadwick. “The Politics of Farrah’s Body: The Female Icon as Cultural Embodiment.” The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 37, no. 1, 2003, pp. 83–104.

Upp Pellegrini, Shauna. “Her Story: Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman-Hughes.” She Made History, 4 Mar. 2021, http://shemadehistory.com/dorothy-pitman-hughes-and-gloria-steinem/.

Wickström, Alice, et al. “Feminist Solidarity: Practices, Politics, and Possibilities.” Gender, Work, and Organization, vol. 28, no. 3, 2021, pp. 857–63,https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12689.

Wynn, Dan. “Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes.” National Portrait Gallery, 1971, https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.2005.121. 1 May 2023.

Zirin, Dave. “Fists of Freedom: An Olympic Story Not Taught in School.” Zinn Education Project: Teaching People’s History, 2012 June 23, https://www.zinnedproject.org/if-we-knew-our-history/fists-of-freedom-an-olympic-story-not-taught-in-school/.

End Notes

[1] A “women’s culture” is distinguished by a view that women inevitably have something in common and need a conversation that feels intimate and revelatory (Berlant 5).

[2] Dorothy Pitman Hughes passed away on December 1st, 2022 at the home of her family in Tampa. She was 84 years old (Noveck).

[3] Nicole Fleetwood traces Davis’ perspective on the uptake of her aesthetic during the early 70s. She summarizes: “Davis explains how the attack on black radical and progressive thinking and style during the era subjected many, Afro-wearing black women to routine stops and searches by law enforcement. Yet she notes as well how the Afro has become aestheticized and depoliticized as fashion and style for consumer culture” (68).

[4] They also add that photographs are a particularly apt medium for enacting this phenomenon because they are a mute record of social performance.

[5] For more on the context of Smith and Carlos’ demonstration at the 1968 Olympics, please visit: https://www.zinnedproject.org/if-we-knew-our-history/fists-of-freedom-an-olympic-story-not-taught-in-school/

[6] It would take decades before their stance would be nationally celebrated and the athletes seen as heroes of racial protest. In 2005, San Jose State University unveiled a 22-foot high statue of their protest titled Victory Salute. In most cases, lasting iconicity takes time to cement itself in the public imagination, where meaning can surface beyond first impressions and the social mores of a given time period.

[7] This is further supported by the caption under the photograph in Esquire’s original printing. It reads: “Body and Soul. Gloria Steinem and her partner, Dorothy Pitman Hughes, demonstrate the style that has thrilled audiences on the Women’s Liberation lecture circuit” (Levitt 89). The term “thrilled” has a positive connotation.

[8] A limitation of this approach is in the 22-years between the creation of the original image and the creation of the internet for public use in 1993, which did not promise universal access. In addition, the evolution of the internet and computer software has made early communicative platforms obsolete and unreachable. However, I was able to collect 84 meaningful hits (out of 835 total hits) published between 2000 and 2021, searching until I did not come across any new hits. The collection includes hits featuring the image alongside text, all of which refer to the image as iconic and feminist. This collection cannot account for the existence of the image in posters on walls, t-shirts, collages, and other meaningful manifestations.

PDF

PDF