Radically Revising the Writing Classroom: Wendy Bishop as Feminist Mentor

Radically Revising the Writing Classroom: Wendy Bishop as Feminist Mentor

Peitho Volume 26 Issue 1, Fall 2023

Author(s): Amy Hodges Hamilton and Micaela Cuellar

Amy Hodges Hamilton, PhD, is a Professor of English at Belmont University, where she focuses on writing as a tool for healing trauma. She serves as Belmont’s Title IX Faculty Liaison and Victim’s Advocate and coordinates the annual Women’s History Month celebration. In 2019, she was the recipient of Belmont’s Presidential Faculty Achievement Award. Her work has been published in the South Atlantic Review and The Feminist Wire, and she has contributed chapters to volumes such Critical Trauma Studies. In October 2019, she served as Writer in Residence at the Seamus Heaney Center at Queens University, Belfast. Amy was recently named a recipient of the 2023 Harold Love Outstanding Community Service Award, a yearly recognition presented by the Tennessee Higher Education Commission. She was Wendy Bishop’s last Ph.D. student at Florida State University.

Micaela Cuellar (she/her) is a PhD student in Rhetoric and Composition at Florida State University. Her research lies at the intersection of composition and literacy studies and considers the way writing facilitates healing both for individuals and communities at large. Micaela is passionate about teaching writing in and outside of the classroom, as shown through her previous work at Healing Housing, a women’s sober living home in Franklin, TN, in which she, alongside Dr. Amy Hodges Hamilton, co-taught a Trauma Writing Workshop with women recovering from drug and alcohol abuse. Micaela recently served as a Teaching Associate for FSU’s Program for Instructional Excellence during which she chaired the Pedagogy Committee and hosted the Annual Spring Book Club. She looks forward to joining the College Composition Program as a mentor to incoming TAs later this year.

Tags: feminist mentoring, pedagogy, radical revision, writing“It takes encouragement and courage to find a clear passage to affirming oneself as a teacher within an institution that valorizes almost every other role first.”

– Wendy Bishop, “Places to Stand: The Reflective Writer-Teacher-Writer in Composition”

Cheryl Glenn’s analysis of rhetorical feminist mentoring is an apt description of how Wendy Bishop mentored until the day she died in 2003. Glenn defines feminist mentoring as “a generative model of ever-expansive teaching” and acknowledges that as such “we academics ‘embody’ the discipline for the next generation of scholars and it passes along…values, theories, habits, and assumptions that, especially when transformed, keep the discipline rolling” (173). This is exactly how Bishop mentored, and as I, her last graduate student, consider the power of her teaching and mentorship on the twentieth anniversary of her death, the reflection I shared at her memorial still rings true:

Wendy Bishop was my mentor, teacher, fellow writer, major professor, and friend, so it was impossible for me to find a way to adequately express my love and respect for her. She always encouraged me to read through things I had written when I was blocked, so I took her advice and began to read things we wrote to each other. I am going to read the last paragraph of the process memo I wrote to Wendy in a research methods course I took with her in Fall 2002, because it is much of what I would like to write to her now:

This process narrative is the last text I will write to finish my course work and begin studying for exams, and I am so grateful for the experience of this course and your teaching. Your knowledge and love for students and writing has been evident in every course I have ever taken with you (and my first class with Wendy was an advanced article and essay workshop in 1996), Wendy, and I will never forget your grace, your guidance, and the knowledge you have shared with me and countless other students. I came alive as a researcher and member of the Composition field this semester, and I have you to thank. It is my goal as a teacher and researcher to share with others all you’ve shared with me.

I have never forgotten that goal and always strive to emulate Bishop’s pedagogical and theoretical approach to teaching, the field of Composition Studies, and, perhaps most importantly, the mentoring of my own student-writers like Micaela Cuellar. Bishop was a pioneer in the ways she challenged scholars, writers, and students alike to explore texts creatively and analytically, to radically rethink the essay form, and to collaborate and to engage in interdisciplinary work with and for students. Bishop shared this commitment in her 2001 chair’s address at the Conference on College Composition and Communication: “I have long been one who preferred to be among others only if I can choose my own way” (CCCC 326). Bishop chose her own way by moving in and out of the traditional English department coverage model, all while including students, from Literature, Creative Writing, and Composition, in the conversation. As Art Young describes in the foreword to Composing Ourselves as Writers-Teachers-Scholars, Bishop was one of the first to “call for boundary-crossing conversations about pedagogy and theory, about students and classrooms, and about individual and social purposes for writing and for teaching writing” in ways that have made space for progressive scholars of today and those in the future to dissolve arbitrary boundaries and promote inclusivity and exploration (vii). Wendy Bishop was a radical feminist mentor, as evidenced through her research, mentorship, and teaching practice.

Wendy Bishop as Radical Feminist Mentor

To most effectively analyze Bishop’s impact on the field of feminist rhetoric, we must first consider how her scholarship paved the way for feminist scholars across English Studies. During Bishop’s twenty-five years as a teacher-scholar, she led what colleagues Patrick Bizzaro and Alys Culhane define as a “a quiet revolution” and served as a leader in both Composition and Rhetoric and Creative Writing, holding executive positions in both the Associated Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) and the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC). Bishop earned an MFA in Creative Writing and a Ph.D. in Composition and Rhetoric and insisted on merging both creative writing and composition studies into her prolific research, publishing 22 books and hundreds of articles and creative writing pieces. In all of this work, Bishop resisted the limitations of singular labels and declared, “For me, to be only a poet, or a feminist, or a compositionist is not enough” (341). As Bishop further shared in one of our class freewrites during Amy’s PhD program and later published in “Because Teaching Composition is Still (Mostly) Teaching Composition”:

I do not believe I can have a smorgasbord pedagogy, but if I do feel entitled to range widely, as a teaching generalist, as a writing specialist, then I’m obliged to think systematically about my practice, even if I do so in snippets of time—at the market, on the commute, between classes, during the department meeting. I am obliged to define, refine, name and explain my practice and to build new knowledge from which to set out again. It is the building and the appreciating and the setting out strongly that matters to me. Writing teachers who get up each day and do their work are doing their work; they do not have to apologize for having values and beliefs, for coming from one section of a field and for moving—perhaps—to another section—from one understanding of instruction to another understanding of it—as long as they are willing to talk, to share, to travel on in company. (77)

This traveling on in company is how Glenn differentiates rhetorical feminism from feminist rhetoric, which she defines as “a set of long-established practices that advocates a political position of rights and responsibilities that certainly includes the equality of women and Others” (3). Bishop agreed that women and other minoritized voices in the academy are always at risk of further silencing and marginalization and believed an interdisciplinary approach within English studies could provide a “formidable challenge to the status quo” (qtd. in “Learning” 344). One way Bishop pushed against these boundaries was to include the voices of students in her scholarship, particularly those we might not have heard from previously (344). Bishop was more interested in the creation of texts than the theorizing of them, particularly from those historically ignored. In Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins speaks to the power of feminist mentorship, as it specifically pertains to Black “community othermothers,” and she connects education and mentorship directly to political activism when she writes that “families and community mentors imbued the highly educated Black women in her study with a determination to use their education in a socially responsible way” in reference to historian Stephanie J. Shaw’s What a Woman Ought to Be and to Do (189). Though Bishop’s positionality did not reflect that of a Black woman, she still sought to use her education to promote inclusivity in the classroom (and academy at large) by centering students’ voices and experiences. Shaw describes the impact and role of these feminist community mentors stating, “these women became not simply schoolteachers, nurses, social workers, and librarians; they become political and social leaders” (Shaw as qtd. in Collins 190). Through her radical feminist mentorship, Bishop, too, served not only as a teacher but also as an othermother, collaborator, and social leader within her writing community. “Learning Our Own Ways” illustrates Bishop’s commitment to feminism and to valuing the voices of marginalized student-writers. As Alice Rosman reminds us, “Her contention that storytelling and narrative are powerful ways to build bridges between these marginalized cultures and the dominant ones is one that carried through the entirety of her scholarship” (64). Bishop also acknowledges connections between her creative approach and theories in anthropology and feminism, which we would argue is radical feminist mentorship:

Postmodern anthropology and feminist theory suggest alternative ways of reporting both practice and research—honoring story, testimony, observational anecdote, informal analysis, regularized lore and so on—and these movements may connect some of us back to our humanistic roots as writers and readers of fictional and factional texts. (Teaching Lives 319)

As a writer, teacher, and scholar, Wendy Bishop actively worked to deconstruct unnecessary boundaries within the academy, the English Department, and in the classroom. In her 1999 essay “Places to Stand: The Reflective Writer-Teacher-Writer in Composition,” Bishop reflects on her career, stating: “All the years, 1-20, I’m teaching. Teaching writing. Teaching writing as a writer. Wondering how it could be any other way” (21). Bishop emphasizes the ways she sees herself as both writer and a teacher with a goal of mentoring and collaborating with her students both in and outside of the classroom. In reflection of Bishop’s mentorship, Stephanie Vanderslice cites collaboration as the way she deconstructed boundaries: “collaboration was second nature to Bishop” and “she not only enjoyed what I think of as the highest kind of discourse—an intellectual give and take rather than rabid attack-and-retreat turf-guarding that can characterize others in academia—but that she also shared the wealth, often inviting others to converse and co-author” (3). Always cognizant of her role as a professor, Bishop is also aware of and considers the limitations of labels in the hierarchical system she sees existing within English departments, including the label of “feminist”, as noted in her essay “Learning Our Own Ways to Situate Composition and Feminist Studies in the English Department”:

When we label ourselves in this way, we agree to the dominant method of distinguishing areas in English studies, what Gerald Graff calls the field-coverage model, a model that isolates and elevates the literature scholar and critic and isolates but devalues the generalist…. By creating separate women’s studies programs, designating fields like “composition” and “feminist studies,” or allowing only minimal authority for writing program administrators, the establishment is free to conduct department business as usual. Meanwhile, marginalized cultures within or beside the department’s dominant culture, alienated, co-opted or about to be co-opted, sit silently around that meritocratic table, feeling concerned. (339)

In their 2006 book Keywords in Creative Writing, Bishop and Starkey deconstruct the master-apprenticeship analogy ever present within academia in a manner that speaks to the institutionalized inequity that the academy has yet to rectify when they write, “while this hierarchical model may have functioned effectively centuries ago… it is problematic in the democratic and multicultural twenty-first century” (122). Their critique of this system calls out the colonial nature of teacher-student relationships within the university that are directly tied to power and the possession of knowledge as power and control, writing, “One obvious inconvenience is that the master-apprentice system tends to reproduce an image of ‘genius’ held by those in power” (Bishop and Starkey 122). Bishop and Starkey highlight an excellent point in their rejection of the master-apprentice analogy by not only bringing the suppression of minoritized voices to the forefront but by subsequently noting that having students emulate the scholarship and writing of instructors ultimately limits the possibility for new, revolutionary scholarship across the curriculum.

Though Bishop passed before the conversations of decolonizing composition and the academic classroom took place, we are reminded of her devotion to inclusive pedagogies, as evidenced through her reflections on teaching and the experiences of those she mentored. In their article “Decolonizing the Classroom: An Essay in Two Parts,” Reanae McNeal and Peter Elbow describe the importance of decolonization within the English classroom:

Decolonial pedagogies require that we honor our web of relations by being deeply aware of each one’s valuable contributions and our connections with each other…. The voices and personhood of our marginalized relations become an imperative aid to understanding the complexities of diverse knowledge systems and multiple lived realities. In order to address current atrocities, historical trauma, and colonialism we must create strong braids of awareness that are sturdy bridges to new stories. These stories help us reimagine the world as diverse global citizens: a reimagining grounded in the promotion of justice for all, including the Earth. In this fashion, what we braid and how we braid knowledge systems in our classrooms is so important. (21)

A self-described “social expressivist” (although she preferred no labels), Bishop blends the fields of creative writing and composition in a way that encourages students to be better writers both in service of themselves (expressivist) and in their larger communities (social) (Teaching Lives viii). In doing so, Bishop, in her own pedagogy, writing, and classroom, seeks to “create strong braids of awareness that are sturdy bridges to new stories,” as McNeal and Elbow describe. Much of Bishop’s teaching of writing stemmed from her own learning and experience as a writer. In interrogating the writing processes of herself and her students, whom she often wrote in communion with, she incorporated the findings into her classroom and her scholarship. When describing what brought her to her unique blending of creative writing and composition studies, Bishop writes:

Writing captured me and composition helped me understand that captivation. After unbraiding and uncomposing my selves within the academy in order to learn specialized skills and certain discourses, in order to participate in elect and select societies, I decided intentionally to rebraid and recompose my self through teaching creative and compositional strategies together. (“Composing Ourselves as (Creative) Writers” 219)

Bishop and her legacy are crucial to the future of composition studies as we continually seek to deconstruct unnecessary demarcations between the personal and the political, the scholarly and the creative. She theorized the braiding of two fields as an act of rebellion—a “quiet revolution”—in which she challenged the dominant perspective of composition as a field and teaching as a profession. Bishop radically revised the role of the composition instructor, and, in doing so, she made the classroom more inclusive and welcoming for all by composing with students, inviting them to collaborate in her publications, and by thinking radically about what it means to compose and revise in the field of English Studies.

Moving Feminist Rhetoric into Practice: The Radical Revision

In order to move Bishop’s feminist rhetoric into practice, we must remain attentive to how an embodied sense of identity is always linked to rhetorical action as Glenn calls us to do. This principle can act as a guiding force for our field, both professionally and in our activism. Bishop defends her choice to do this in her essay “Places to Stand: The Reflective Writer- Teacher-Writer in Composition”:

I do my mixing, not to elevate genres but to intermingle them, not to venerate the poetic or belletristic but to point out that each brings us to our senses though in different modes and tones. Because styles, genres, and syntax seem both to prompt and predict thought, I need to think in and through them all. (17)

One of the first practical experiences Amy had with radical feminist mentorship came in the way of a revision project Bishop assigned in her 1998 upper-division writing workshop at Florida State University. Bishop assigned a “radical revision” of a previously completed text, where students were invited to consider changes in voice/tone, syntax, genre, audience, time, physical layout/typography, or even medium. Today, this project could be classified as one that promotes multimodality or that asks students to “decolonize the essay” from its traditional form. In addition to the radical revision, students were also asked to write a letter of self-reflection that explained the process and radical revision in detail (Appendix A). This assignment opened up possibilities for how to revise outside of what is often viewed as acceptable in academic discourse, and Bishop was ahead of her time, once again, with the introduction of multimodal composition and alternative discourses. She invited students to consider what discourse and modality best fit their writing, providing students agency over their stories and writing and encouraging instructors to adjust assessment accordingly. Amy chose to create a poem after writing her literacy essay on a lifelong search for love through words:

I Think of My I Love Yous,

of all my I’ll waits and I promises,

so sad, our sea of failed words,

like stars that fall too far off,

faint and alone in the sleeping sky.

But the always and the nevers

keep speaking somewhere—

only listen for the echo of our parallel lives,

the way a subway violinist haunts us,

a church of sound on our way

to somewhere else, or that rare rush

of air in a mall, a smell that stops us,

chilled, makes us mouth

someone’s name.

It was such an eye-opening experience that Amy, and now Micaela, assign it in every writing course and continue to be amazed at how it shifts students’ understanding of discourse, writing, and revision.

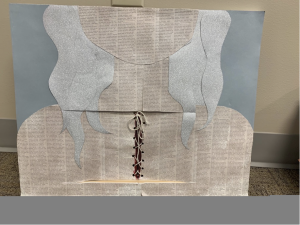

Micaela reflects on her experience with the project in Fall 2015: “I found this particular assignment to be my favorite of the class…When approached with the task of taking one of our essays and transforming it from one form of art to another, I was excited.” For her radical revision, Micaela chose to visually create a metaphor she used in her personal essay from earlier in the semester. When speaking of her goals for the project, Micaela writes, “My biggest challenge while creating this was hoping readers would get it and that it would be an accurate representation of how one feels when going through a difficult situation.” In the process letter, Micaela emphasizes how the process of creating the radical revision unknowingly seemed to align with the experience she wrote about, but this time she had agency over it. She created the radical revision, and she was able to choose how to share it.

Image description: an example of a radical revision: a collage showing the lower half of a person’s head and their shoulders. The background is made of blue-gray paper with variegated lighter and darker shades. The person’s hair is made from silver paper, and the face, neck, and shoulders are made from paper with printed text. In the middle of the person’s chest is a vertical cut with holes at the edges. String is used to lace up and tie together the vertical cut.

The radical revision project, first published in Bishop’s Elements of Alternate Style (1997), invites students to shift their essay’s style, perspective, or genre. Through this final revision project, student-writers are invited to reflect on their growth throughout the writing process by revising their essay in a radical way and into a different genre or form. Bishop writes that the radical revision moves us to an informal, narrative research writing style that “allow[ed] [her] to investigate ethical, political, and writerly concerns more freely” (216). The radical revision requires students not only to wrestle with the challenges of reconceiving their previously finished work but also encourages them to consider how they define revision and how they chose to learn to deal with its limitations. In “Distorting the Mirror: Radical Revision and Students’ Shifting Perspective,” Kim Haimes-Korn presents the radical revision assignment and reminds us that the radical revision “involves seeing and seeing again and how shifts in style and perspective can help us write, think, and learn” (95). Overall, if one of our main goals as teachers of writing is to share the power of rhetoric with students, then why not take a risk and move differing forms of that rhetoric into our pedagogical designs? In other words, Bishop calls us to break out of our “comfort zones” and get radical in the writing classroom by moving past theory and into practice.

Carrying Radical Mentoring On: Student-Mentee Reflections

Amy, Wendy Bishop’s Final Graduate Student, 1998-2003: Even as an undergraduate student, I was intrigued by the uniqueness and effectiveness of Bishop’s assignments, and I could tell she was much more humble than she should be. Of course, I was right. She was, by the late nineties, one of the strongest voices in the field of composition in terms of her publications and professional engagements, as well as an endowed chair in the Department of English at Florida State University. Yet in class, she wrote with us, shared with us, and always entered into writing exchanges as our equal. In “Learning Our Own Ways to Situate Composition and Feminist Studies in the English Department,” she supports the need to critically challenge students: “Since graduate students clearly represent great potential for English departments, we should explore public and private channels for teaching these soon-to-be-peers critical consciousness […].These students have the potential to make the changes within the house of English studies we have sometimes despaired of making” (133). Bishop and Glenn offer alternatives to traditional, master-apprentice models of mentoring through non-hierarchical, mutual, and networked collaboration. Glenn also points out that such mentoring is the way rhetorical feminists give each other hope and make space for each other in what has traditionally been a privileged and exclusionary white, male space, and that was my experience as a student of Wendy Bishop.

I was distracted by the bright Florida sunlight that bounced off one of the many bookshelves lining Dr. Bishop’s office and almost missed what she asked. Or maybe I didn’t believe she could really be asking me, a first-year Ph.D. student, to co-author a chapter on the power of letter writing as a way to process loss and trauma. I squinted her way and said yes even though I wasn’t exactly sure what I was saying yes to. And she continued to ask me to collaborate—on CCCC panels, in chapters, pedagogical workshops, and in conversations over coffee about her research and the teaching of writing. Because of the power of this mentorship, of being valued, I have looked for opportunities to mentor in my teaching and writing life.

Even though I didn’t think I was adding much to the scholarship when working alongside Wendy, which she insisted I call her rather than Dr. Bishop, I now know that was likely untrue because of the ways my teaching and research have been deepened through mentorship and collaboration with my own students. Micaela, a student who didn’t even know she wanted to go to college, is an example of how carrying mentorship forward is both radical and vital to the future of our field.

Micaela, Amy Hodges Hamilton’s student, 2015-2018: Eight years ago, I sat in my first college class, Amy’s first-year writing course, and I finally felt that I belonged somewhere. A high-school drop-out by the age of 16, I was persuaded to attend college two years later as an escape from the small Texas town in which I was raised. To my surprise, I found my home within the four walls of a classroom where the desks were arranged into a circle and the space was made complete with a professor and strangers-turned-friends who comprised a community of writing, researching, and collaboration founded on mutual respect and care for each other and their stories.

As a white Latina student, I always struggled to articulate the complexities and privileges I experienced throughout my life due to my race, ethnicity, and the pronunciation of my name. However, with Amy’s guidance and through workshopping with my peers, I sought to interrogate my own identity by telling stories through memoir, essays, art pieces, and research—all of which I was encouraged to explore in Amy’s class. Prior to this, I’d never experienced education in such a communal way. I was moved by the rhetorical, pedagogical choices Amy made in the classroom, such as: sitting amongst her students, as opposed to traditionally standing in the front of the classroom, writing and sharing with us during class, especially during freewrites, and prioritizing connection and collaboration through individual conferencing and half-class workshops. Though I couldn’t have articulated it at the time, I wholeheartedly believe the sense of belonging I (and many others) felt can be attributed to the radical feminist pedagogy and mentorship Amy has carried on from Wendy.

In my second semester of college and another course of Amy’s, I approached her after class one day, letting her know I was considering changing my major to English. In that moment, Amy led me to her office, and we began discussing the English major and possible graduate programs and career choices in and outside of the academy. Quickly, these conversations shifted from undergraduate advising to research possibilities, collaborations on campus-wide social justice initiatives, service-learning opportunities, and, later, the chance to co-teach a writing workshop with marginalized women in the community.

There are days when I lie beneath the Spanish moss, shading myself from the warm Florida sun, that my heart burns with immense gratitude for Wendy Bishop and her legacy that lives on through my forever-mentor and friend, Amy. As a third-year PhD student studying to take my preliminary exams, I carry the teachings of Amy and Wendy with me as I enter what I hope will become a decades-long career of teaching, writing, and dissolving the boundaries between the academy and the community. Whether she knew it or not, Wendy forged her own genealogy within composition studies—one I am lucky to be a part of—and it is privilege to have a hand in carrying on her legacy and expanding upon her creative, empowering, and inclusive scholarship that changed the way I understand writing, the classroom, and the true meaning of teaching. As Bishop reminds us, “…teaching is visionary and spiritual—it is what matters—and I return faithfully to the classroom year after year, needing that growing space, no doubt, as much or more than the classroom inhabitants need me” (Teaching Lives 314).

A Call to Radical Feminist Mentoring

From reading and re-reading Bishop’s scholarship, we think she would argue that to most effectively act as rhetorical feminist mentors, we must all, beginning and established scholars alike, write with and about students. In both her teaching life and scholarship, Bishop believed in the power of connecting these two sometimes dichotomous roles. In “Places to Stand: The Reflective Writer-Teacher-Writer in Composition,” Bishop urges “…teachers [to] write with and for their students as well as with and for their colleagues” (9). Glenn, too, insists, “teaching is hope embodied. It is a forward-looking endeavor, one that has the power to change lives—our own, our students” (125). Glenn suggests that rhetorical feminist teachers should acknowledge their own positionality, respect students’ experiences, and help students investigate patriarchy and other compounding injustices in the world. To be an intersectional feminist capable of effecting positive change in the classroom and academy, it is our responsibility to demonstrate inclusion, equity, and decoloniality in all aspects of our pedagogy. Bishop did this as an early advocate of ethnographic inquiry, a research method designed to give voice to writers and writing practitioners we may not have otherwise heard from. Equipped with these inclusive writing practices, students and teachers are prepared “to develop rhetorical agency” and change the status quo, prompting us to see how our work matters and how our political commitments can guide our professional actions (148).

We can begin by doing what Bishop did throughout her mentorship and scholarship—share stories, write with and about our students, and mentor the next generation of feminist rhetoricians. As she articulates in “Teaching Lives: Thoughts on Reweaving Our Spirits,” “…teaching [and mentoring] teaches me, heals me, helps me, centers me in my professional and personal life in a way I’ve seldom seen talked about” (314).

It’s time to talk.

Works Cited

Bishop, Wendy. Elements of Alternate Style: Essays on Writing and Revision. Boynton/Cook Publishers, 1997.

—. “Steal This Assignment: The Radical Revision.” Practice in Context, edited by Cindy Moore and Peggy O’Neill, NCTE, 2002, pp. 205-222.

—. “Places to Stand: The Reflective Writer-Teacher-Writer in Composition.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 51, no.1, 1999. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/358957.

—. “Teaching Lives: Thoughts on Reweaving Our Spirits.” Teaching Lives. Utah State Press, 1997. pp. 313-320.

—. “Traveling Through the Dark: Teachers and Students Reading and Writing Together.” Teaching Lives. Utah State Press, 1997. pp. 104-118.

—. “Because Teaching Composition Is (Still) Mostly about Teaching Composition.” Composition Studies in the New Millennium: Rereading the Past, Rewriting the Future. Southern Illinois University Press, 2003. pp. 75-77.

Bishop, Wendy, and David Starkey. “Pedagogy.” Keywords in Creative Writing. Utah State University Press, 2006. pp. 119-125. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.cttcgr61.28.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd ed. Routledge, 2000.

Glenn, Cheryl. Rhetorical Feminism and This Thing Called Hope. Southern Illinois University Press, 2018.

Haimes-Korn, Kim. “Distorting the Mirror: Radical Revision and Students’ Shifting Perspectives.” Elements of Alternate Style: Essays on Writing and Revision. Heinemann, pp. 88-95.

McNeal, Reanae, and Peter Elbow. “Decolonizing the Classroom: An Essay in Two Parts.” Writing on the Edge, vol. 28, no. 1, 2017, pp. 19–32. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44647497.

Rosman, Alice. Wendy Bishop: A Feminist Voice at the Intersections of Composition, Creative Writing, and Ethnography. 2013. Oregon State University, M.A. Thesis. ScholarsArchive@OSU,ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/graduate_thesis_or_dissertations/pc289m400.

Sommers, Jeff. “Revisiting Radical Revision.” Critical Expressivism: Theory and Practice in the Composition Classroom, The WAC Clearinghouse, 2015. DOI: 10.37514/PER-B. 2014.0575.2.18.

Vanderslice, Stephanie. “There’s An Essay in That: Wendy Bishop and the Origins of Our Field.” Journal of Creative Writing Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2016. https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol1/iss1/2/.

Appendix A

Radical Revision Guidelines

- Choose Essay I or II (you may not want to choose Essay II, because you just finished writing that essay and you may be too close to it, making you reluctant to jump in and play with your text).

- You will revise this essay in a way that challenges you to take risks and try something you’ve never tried before as a writer and analyst in this class.

- The revision can end up less effective than the original (there’s no real risk-taking without the possibility of failure). Remember the revision process is an important part of the overall writing process. You must be willing to re-evaluate and analyze your texts again and again to become a successful writer.

- The core of the radical revision assignment is your process, which will include:

- A process letter (one page single spaced minimum) where you recount what you chose to do, why—why is this a risk/challenge for you as a writer, how it worked, and what you learned—see questions below.

- All drafts/notes/peer review sheets that encouraged your revision.

- The final radical revision (or a photo).

- Class presentation or reading/explanation of your revision.

Process Letter Questions–Radical Revision

This letter will inform your reader of your goals for this radical revision and how those goals were accomplished. These may include learning about drafting from changing a text from one style to another, taking risks, pushing boundaries, attempting difficult tasks in order to learn more about yourself and your writing style. Please write this as a personal letter to me, and answer six of the following eight questions. Be sure to add any information that you think will help me evaluate your radical revision. Remember, your process letter should be 1-2 pages single-spaced.

- Tell me in some detail about the drafting particulars of this project—where did you start (ideas and drafts) and where did you go (how many drafts, revisions, taking place where, for how long, under what conditions)?

- What were your goals for this piece? Where are you challenged? What did you risk in revising your essay in this way?

- Who is the ideal reader/audience? What should she/he bring to the text in order to give it the best reading/interpretation?

- If you had three more weeks, what would you work on?

- According to your own goals for this project, estimate your success. Be specific and perhaps quote from sections of the text or point to a particular aspect of the project.

- What did you learn about yourself as a person and writer from this project? How was this process healing?

- You’ve given this to your peers and they say, “we like it, but…” How did your responders help or hurt your revision efforts?

- How would you evaluate yourself? Do you feel like the radical revision was a success for you as a writer? What did it show you about your focus/your life story?

To radically revise, students are invited to try one or more of the following:

- Voice/Tone Changes? Change from first to third or try second; write as a character, change tone (serious to comic, etc.), change point of view from conventional expectations, change ethnicity, change perspective, use stream of consciousness, use the point of view of something inanimate, use a voice to question authority of the text OR change from adult to child to alien, try parody or imitation

- Genre Changes? Nonfiction to poem to song to ad campaigns, bumper stickers, letters, sermon, journal, fairy tale, recipe, prayer, cartoon, short story

- Time Changes? Future (flashforwards/flashbacks), present to past, tell backwards, situate in a different era or time, change expected climax/central idea of essay

- Multimedia/ “Art” Piece Performance (monologue/dialogue), play, audio and or video, art illustration (canvas, collage, watercolor, etc.), write on unexpected objects (shirts, shoes, walls), choral performance, mime

***push your text, fracture, bend, break conventions, think about emphasis, importance, and detail as a writer. How will your central idea be clearest for the reader/observer? You are going to break conventions in order to learn about the importance of analysis in EVERY context (art, research, film, music, literature, math). As you write, notice the progression of your ideas and the progression of your text (you will explore this in your process cover sheet)***

PDF

PDF