Living and Dying as a Gay Trans Man: Lou Sullivan’s Rhetorical Legacy

Living and Dying as a Gay Trans Man: Lou Sullivan’s Rhetorical Legacy

Peitho Volume 22 Issue 4 Summer 2020

Author(s): K.J. Rawson

K.J. Rawson is an Associate Professor of English and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Northeastern University. He is also the founder and director of the Digital Transgender Archive, an award-winning online repository of trans-related historical materials. Rawson’s scholarship has appeared in Archivaria, Enculturation, Peitho, Present Tense, QED, RSQ, TSQ, and several edited collections.

Abstract: Louis G. Sullivan, a groundbreaking trans activist who forged some of the earliest trans peer support networks in the U.S., engaged in a series of videotaped interviews between 1988-1990 with psychiatrist Ira B. Pauly. This brief article offers a rhetorical analysis of selections from those interviews in order to introduce readers to Sullivan’s rhetorical strategies for persuading the “gender profession” that it was possible to be both trans and gay or lesbian.

Tags: activism, Digital Transgender Archive, gay, Lou Sullivan, psychiatry, transgenderOver the course of three years, from 1988–1990, activist Louis (“Lou”) G. Sullivan engaged in a four-part series of videotaped interviews with psychiatrist Dr. Ira B. Pauly. Titled Female to Gay Male Transsexualism, the tapes of the interviews were used for many years after they were created, including by Pauly at academic conferences and by Jamison Green in college classes (Smith, Personal Interview).1 The full recordings of these interview are now held by the GLBT Historical Society and have been recently made available on the Internet Archive and linked to on the Digital Transgender Archive. In addition to the full videos available on the Internet Archive, Reverend Megan Rohrer has made twelve short excerpts from these videos available on YouTube (see Appendix A). The twelve video clips are brief, thematic excerpts taken from the hours of original conversations and they provide a helpful starting point for those interested in beginning to explore Sullivan’s rhetoric. In this short essay primarily focused on one of those clips—“Lou Sullivan: Battling the Gender Specialists 1989” (see Fig. 1), which is an excerpt taken from Pauly’s third interview with Sullivan in 1989–my aim is to offer a preliminary introduction to the rhetorical approach that Sullivan used to advocate on behalf of trans people.2 Throughout his conversations with Pauly, Sullivan exercised impressive rhetorical savvy as he worked to educate doctors about trans issues, and in particular, as he argued for the viability of being a gay trans man.

When Sullivan and Pauly came together for these one-on-one conversations, they seemed to be at once meeting as like-minded allies of trans people and facing off in their respective roles as patient versus doctor. From the late-1950s through his retirement in 2010, Pauly had a long and prolific career focused on researching and treating transsexual clients, serving as the president of what is now the World Professional Association for Transgender Health from 1985-1987 and often working alongside Dr. Harry Benjamin (Devor; Zagria). Though Sullivan’s life was cut short in 1991 at the age of 39, he was a highly influential white, gay, trans activist who is particularly known for his creation of peer support networks for trans men and his passionate advocacy for gay and lesbian trans people. Biographer Brice Smith explains that by the end of his life, Sullivan was “credited for the role he played in fostering the trans movement” (231). Sullivan’s legacy has only continued to gain recognition in the decades since. Pauly and Sullivan were thus well-positioned to conduct these conversations, with the one-on-one format casting Sullivan as a spokesperson for trans people while Pauly represented the field of psychiatry and, more broadly, medical professionals who worked with trans patients.

These conversations occurred during a kairotic historical moment when tensions concerning medical treatment for trans people mounted as increasing numbers of trans people sought transition-related medical care and medical professionals rapidly tried to determine standards of care for treatment. Tensions arose as medical professionals determined who was eligible for treatment and what criteria must first be met, often resulting in gatekeeping practices and outright refusals of care. Sullivan himself faced this problem time and again when he sought medical support for his transition from female to male beginning in 1976 and continuing through the 1980s. Sullivan repeatedly experienced discrimination when gender clinics would not take him on as a client and doctors refused to operate on him solely because of his sexuality, because they could not comprehend or support a trans person who was also gay (“Female to Gay Male Transsexualism: I”).

In speaking with Pauly, Sullivan uses his personal testimony as a rhetorical strategy, frequently drawing upon his own experiences to explain what it is like for a trans person struggling to navigate the medical establishment. As he explains in the 1989 interview, “I had a lot of problems with the gender professionals saying there was no such thing as a female-to-gay-male and you can’t live like this and we’ve never heard of that” (“Lou Sullivan: Battling,” 00:04-00:14; Figure 1). Here, Sullivan adeptly sums up three common arguments made by “gender professionals” to prevent his transition:

- gay female-to-male people do not exist (“there was no such thing”);

- only heterosexual people are worthy of treatment (“you can’t live like this”); and

- expertise on this issue was owned by the professionals (“we’ve never heard of that”). Sullivan’s very existence, coupled with his willingness to publicly and articulately testify about being a “female-to-gay-male,” offered a compelling counter-point to all three of these arguments.

Fig. 1. Youtube Video. “Lou Sullivan: Battling the Gender Specialists 1989.” https://youtu.be/SxgZNNX-v2g

Sullivan’s use of personal testimony is all the more striking in moments when he discusses the impact his embodied experiences have had on his activism. He recounts, “when I got diagnosed [with AIDS] and I thought I’ve got ten months to live…and they’re going to hear about this before I kick off. And I don’t want, you know, other people coming into their clinics in two years saying they feel that way [gay] and getting the same line that I did that they never heard of this [a gay trans person] and this isn’t an authentic thing” (“Lou Sullivan: Battling,” 00:15-00:30).3 Sharing an AIDS diagnosis—an uncommon public disclosure in 1989—allows Sullivan to underscore the urgency of his message. What better claim to exigency than a person with ten months to live spending his remaining time advocating for this issue? Sullivan circles back to his AIDS diagnosis again and again throughout his conversations with Pauly and as he does so, Sullivan forfeits his own privacy in the face of tremendous public stigma for those with an AIDS diagnosis. Despite the personal costs, Sullivan prioritizes his rhetorical aims with precision and focus—his goal is to educate gender professionals in order to enable future gay trans people to receive medical care.

In order to combat the discrimination that gay trans people faced, Sullivan needed to make a logical argument that distinguished gender identity and sexuality, which was not a widely held understanding at the time. As he explains, “I guess even in the gender professionals that this is still kind of a new angle that sexual identity…and sexual preference of a partner are two separate issues. That my gender identity, who I think I am, has nothing to do with what I am looking for in a sexual partner. And I think that these two things have been equated. That, well, it’s normal to be heterosexual and if we’re going to make somebody better, that means that we have to make them heterosexual” (“Lou Sullivan: Battling,” 00:46-01:22). With straightforward language and a casual style, Sullivan continues to use his own experience in the first person to advance his argument. He then shifts to using “we” to speak with his audience in order to make explicit the implicit assumption that heterosexual is “normal” and “better.” For gender professionals who would object to being seen as homophobic, this argument would likely be quite persuasive.

Pauly acknowledges the impact of Sullivan’s approach, shifting to first person to speak on behalf of Sullivan; “I think coming forward as you have and saying, ‘hey, you know, maybe my lifestyle and my sexual preference is different than most of these other folks, but I believe I’m as deserving a candidate to live my life the way I wish to, as these other people, and I’m willing to come forward and be counted.’ And I think that’s, I know that’s going to be helpful” (“Lou Sullivan: Battling,” 05:01-05:24). Using the first person to speak from Sullivan’s position, Pauly models the very same empathy and acceptance by a medical professional that is the intended outcome for these conversations. He recognizes the power of Sullivan’s willingness to “come forward and be counted,” of using personal testimony as an argument against the narrow parameters of “normal,” of who was allowed to receive medical treatment.

While Sullivan’s personal testimony is the central focus of these conversations, he still subtly creates space for others in his community. The following exchange offers an illustrative example:

Pauly: In the short period of time since I’ve met you, I’ve heard now of several other cases of female-to-male transsexuals who, in their male role, want a relationship with a man and a gay relationship. So it’s interesting, as you define a new syndrome, certainly at the point where it becomes reported or published, then everybody starts looking and these folks seem to come out of the woodwork.

Sullivan: Right, right. I know just from my contact with other female-to-gay-males that they’ve been afraid to say anything, and especially to any of the doctors that have been helping them because they know that they are up for prejudices and that this is not part of the textbook definition and they don’t want to throw their chances off of getting treatment. (“Lou Sullivan: Battling,” 03:29–04:16)

Pauly’s use of “syndrome” and reference to “reported or published” information lends an obviously clinical tone to his comments. But rather than arguing against Pauly directly and with equally clinical language, Sullivan first agrees (“right, right”) that there are gay trans people. Then, he invokes a larger community that he refers to as “female-to-gay-males,” which is an important revision of “female-to-male” (also shortened to “FTM”), the then-common phrase that Pauly uses repeatedly. Sullivan’s addition of “gay” in FTM inserts a sexual identity where there wasn’t one before. He leaves unspoken that a corollary phrase—“female-to-straight-males”—may seem strange (as naming a dominant position can often be), but it is precisely the unstated precondition for care required by most medical professionals working with trans patients at the time. Sullivan’s use of the new identity term “female-to-gay-male” is one part of his larger effort to explain that there is a broader community of gay trans men whom Pauly, and other gender professionals by extension, are admittedly unaware of. While Pauly may have the sense that gay trans men were “com[ing] out of the woodwork,” Sullivan gently rebuts that by explaining that others have been forced into silence because of the power that doctors wield to withhold treatment.

Given this power imbalance, it makes sense that Sullivan’s target audience in these conversations is the “gender profession,” as he refers to it throughout the interviews. As an advocate for trans people, Pauly helpfully becomes a surrogate for the “gender profession” writ large, modeling for other professionals how to treat trans people as experts by respecting their lived experiences. By casting Sullivan as a subject with knowledge to share (rather than an object of study), Pauly models how gender professionals can learn from trans people as part of their academic and clinical research. Within this framework, Pauly lends a great deal of credibility to Sullivan’s testimony and arguments.

Yet while Pauly is generally sympathetic toward Sullivan and supportive of his aims, there are moments of rupture where he states overtly that he is “a bit defensive about the gender profession” (“Lou Sullivan: Battling”, 04:16–04:19). As Pauly explains, “we have stuck our necks out a bit in even allowing the classic case to be operated on and giving it our good housekeeping seal of approval” (“Lou Sullivan: Battling”, 04:23–04:36). Notably, Pauly speaks for the gender profession with a collective “we,” yet trans people have no subjecthood in this framing as he refers to the “classic case” rather than people. After noting that, “there have been some instances in which the people that have been screened did change their mind after surgery and some of us have been involved in legal suits,” Pauly does begin to refer to patients as people and he switches gears to compliment Sullivan and support his arguments (“Lou Sullivan: Battling,” 04:39–04:49). While many trans people and contemporary viewers of these videos might object to Pauly’s characterization of gender professionals as both courageous trendsetters and sympathetic victims of litigious patients, it’s interesting to consider how effective this approach would have been to the gender professionals in their audience at the time. Indeed, I would argue that Pauly’s position as a representative of gender professionals allowed him to air beliefs that many of his colleagues may have shared, which ultimately may have furthered Sullivan’s advocacy for gay trans men.

In addition to potentially objecting to the content of Pauly’s arguments, contemporary viewers might also struggle to understand how a highly mediated and staged conversation with a trans person could qualify as cutting-edge advocacy work. This distinction in historical context becomes quite apparent within the context of YouTube, an online platform where easy access to vlogging has empowered a generation of trans people to author their own narratives and forge community in ways that were unfathomable in the late 1980s (Raun). While contemporary trans vloggers may take for granted that they are experts on trans experiences and they are able to share those experiences with few barriers, Smith explains that it required a notable amount of resources to videotape the Sullivan/Pauly conversations and it was “unheard of” for a medical professional to position a trans person as an expert at the time (Smith, Personal Interview). Without any other options for spreading his message, Sullivan needed to collaborate with someone like Pauly in order to pursue his rhetorical goals.4

As the two sat together, Sullivan and Pauly not only appear to be allied in their rhetorical aims, but they were also visually aligned as well. In all of the interviews, the two white men sit facing one another, leaning back in their chairs and seemingly very comfortable together. Sullivan wears a shirt and tie in every interview—sometimes also donning a jacket or sweater as well—conveying sartorial ethos that would make him relatable with an audience of medical practitioners who were also, we might safely assume, predominantly white and male. Pauly, while also dressed professionally in button down shirts and sometimes a jacket or sweater, opts not to wear ties. The comparative effect is subtle, but may lend extra credibility to Sullivan, who is clearly comfortable and confident in this situation as he converses with one doctor while trying to change the practices of countless others. Their shared traits—whiteness and maleness, for starters—certainly contributed to their ease with one another and, for contemporary viewers, also offers a helpful reminder that other trans activists seeking a stage for their trans advocacy work would have faced significant barriers the further they were from positions of (relative) power and privilege.

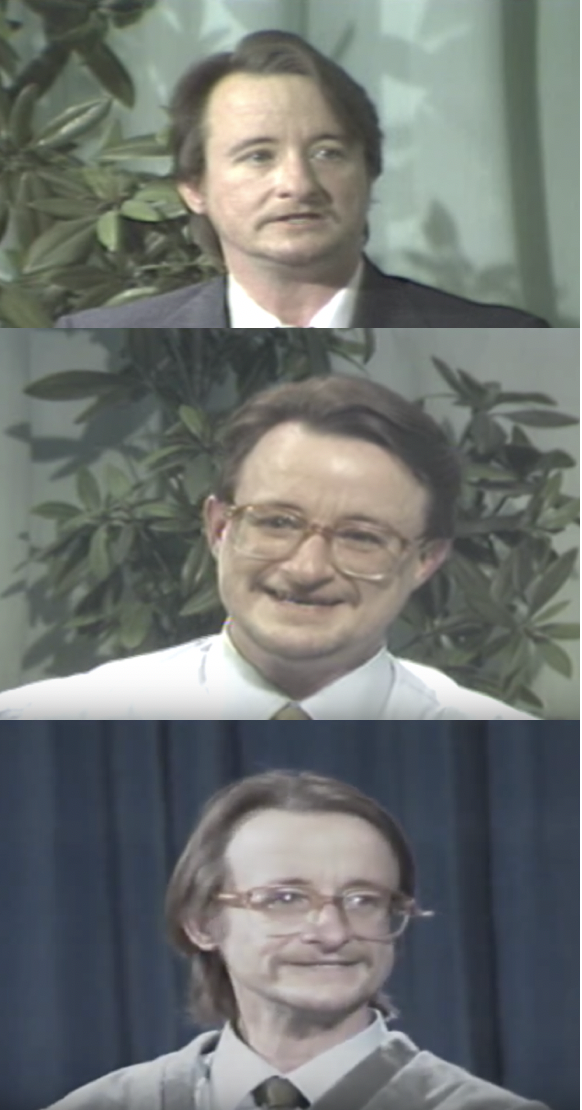

A comparison of Sullivan’s visual presentation across the three-year sequence of videos provides a striking testament to the impacts of disease on his body (Fig. 2). The juxtaposition of video stills taken from across the years shows Sullivan adopting glasses by the second clip, and then becoming increasingly gaunt by the third. His posture, confidence, and professionalism remain consistent throughout the years, but his voice gets softer and his energy is seemingly weakened. It is as if his body is vanishing as the strength of his message is amplified.

Fig. 2. Still images. Sullivan from 1988, 1989, and 1990, top to bottom.

Sullivan’s experience of AIDS was a complicated, if mournful, terminal illness. As he recounts,

“I feel like, in a way, this AIDS diagnosis, because AIDS is still seen at this point as a gay man’s disease, that it kind of proves that I did do it, and that I was successful. And I kind of took a perverse pleasure in contacting the gender clinics that rejected me and said that, you know, they’ve told me so many years that it was impossible for me to live as a gay man but it looks like I’m going to die like one.” (“Female to Gay Male Transsexualism: II”, 26:45–27:12)

Combining his rhetorical strategies of personal narrative and embodiment, Sullivan argues here in the strongest terms for the authenticity of being a gay trans man. While gender clinics may have disavowed his identity, he regains the power of self-identification through his association with a broader community of gay people. Sullivan’s terminal diagnosis provides not only exigency for his activism, but an incredible emotional appeal that underscores the importance of this cause.

Sullivan’s powerful testimony throughout these interviews is not lost on Pauly and he vows to Sullivan, “rest assured that the story will be told and the tape will be shown to the gender profession, as you refer to it” (“Female to Gay Male Transsexualism: I”, 59:36–59:47). As it turns out, Pauly’s reassurances were accurate and Sullivan’s story continues to be told, perhaps more frequently than either of them could have ever imagined and to a far broader audience than the gender profession. As Susan Stryker discusses in her introduction to a recently published collection of Sullivan’s diaries, Sullivan’s story has indeed found “its way to audiences hungry to hear it,” not only through that book, but through Smith’s biography, a dance company production, several films, and increasing publications (viii).

As a rhetor, Sullivan left a legacy of impactful activism that can be rightfully studied under the emergent framework of Transgender Rhetorics. He spent much of his life advocating as a trans person on behalf of trans people, ultimately leaving a notable imprint on both trans community formation and access to medical care. Even in these interviews that are merely brief excerpts from a lifetime of activist work, we gain a meaningful glimpse into the rhetorical savvy that Sullivan exercised, particularly through strategic deployments of personal narrative, logical argumentation, and embodiment. Ultimately, Sullivan offers us profound lessons, in life and rhetoric, about the incredible power of devoting one’s life to helping make trans lives more livable.

Endnotes

- The historical materials referenced throughout this essay use language that has become dated (such as “female-to-male”) or is now considered offensive (such as “transsexualism” and “transvestite”). For the purposes of this essay, I will preserve all historical uses of terminology for accuracy, though I will use “trans” to broadly refer to people who do not conform to the gender they were assigned at birth and I will refer to Sullivan as a gay trans man.

- The titles of these video clips were given by Rohrer, not Pauly. Rohrer digitized the videos as part of a project for outhistory.org called Man-i-fest: FTM Mentorship in San Francisco from 1976-2009, available at http://www.outhistory.org/exhibits/show/man-i-fest.

- Our current understanding of HIV/AIDS makes an important distinction between HIV and AIDS diagnoses. However, for historical accuracy, I follow Sullivan’s lead in referring to his AIDS diagnosis.

- I am grateful to Brice Smith for pointing out the tremendous differences in historical context that YouTube inadvertently flattens.

Appendix: List of Sullivan/Pauly Interviews Currently Available Online

| Title (Provided in Video) |

Date | Length | Link | Notes |

| Female to Gay Male Transsexualism: I— Gender & Sexual Orientation | 1988 | 1h1m56s | https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/4x51hj25d | Full-length interview |

| Female to Gay Male Transsexualism: II— Living with AIDS [1988] | 1988 | 28m58s | https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/fx719m69c | Full-length interview |

| Female to Gay Male Transsexualism: III [1989] | 1989 | 40m57s | https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/00000030q | Full-length interview |

| Female to Gay Male Trans-sexualism Part IV (One Year Later) [1990] | 1990 | 34m22s | https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/8336h219b | Full-length interview |

| “Lou Sullivan on AIDS 1988” | 1988 | 2m52s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DGVDPhGIA7g | Excerpt from part II |

| “Lou Sullivan on AIDS 1990” | 1990 | 7m18s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6hpv7Q9Evc8 | Excerpt from part IV |

| “Lou Sullivan: Honesty, AIDS, and Transition 1988-1990” | 1988–1990 | 5m09s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-j_Zqes8Q8Q | Excerpts from all four parts |

| “Lou Sullivan: AIDS and Sex 1988-1990” | 1988–1990 | 8m29s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xggb5naOppo | Excerpts from all four parts |

| “Lou Sullivan on AIDS 1989” | 1989 | 6m51s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DbK5Ye7aSIY | Excerpt from part II |

| “Lou Sullivan: ‘Genitalplasty’ 1988” | 1988 | 3m52s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ki_p_CyGv4U | Excerpt from part I |

| “Lou Sullivan: Battling the Gender Specialists 1989” | 1989 | 6m13s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SxgZNNX-v2g | Excerpt from part III |

| “Lou Sullivan: Top Surgery 1988” | 1988 | 4m51s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L2j-LOYuHSc | Excerpt from part II |

| “Lou Sullivan: DSM 1989” | 1989–1990 | 1m36s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9A-6g0f3nXk | Excerpts from parts III and IV |

| “Lou Sullivan: Rejected by Gender Clinics 1988” | 1988 | 5m58s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PGmD7F0bmu8 | Excerpt from part I |

| “Lou Sullivan: Changing Standards 1989-1990” | 1988–1990 | 4m23s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nw7xOrLBOic | Excerpts from all four parts |

| “Lou Sullivan: No Regrets 1988” | 1988 | 1m31s | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=epnOWVrGyQU | Excerpt from part 1 |

Works Cited

- Devor, Aaron. “History of the Association.” WPATH. Accessed 18 Oct. 2019.

- “Female to Gay Male Transsexualism: I—Gender & Sexual Orientation.” Interview with Louis Sullivan by Ira Pauly, 1988. Digital Transgender Archive.

- “Female to Gay Male Transsexualism: II—Living with AIDS.” Interview with Louis Sullivan by Ira Pauly, 1988. Digital Transgender Archive.

- “Lou Sullivan: Battling the Gender Specialists 1989.” YouTube, uploaded by Megan Rohrer, 20 Feb 2010.

- Raun, Tobias. “Archiving the Wonders of Testosterone via YouTube.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 2.4 (Nov. 2015): 701-709.

- —. Out Online: Trans Self-Representation and Community Building on YouTube. Routledge, 2016.

- Smith, Brice. Lou Sullivan: Daring To Be a Man Among Men. Transgress Press, 2017.

- —. Personal interview. 29 Oct. 2019.

- Stryker, Susan. “‘My Own Interpretation of Happiness:’ An Introduction to the Journals of Lou Sullivan.” We Both Laughed in Pleasure: The Select Diaries of Lou Sullivan, 1961–1991. Eds. Ellis Martin and Zach Ozma. Nightboat Books, 2019. v-viii.

- Zagria. “Ira B Pauly (1930–) Psychiatrist, Sex-change Doctor.” A Gender Variance Who’s Who, 6 Aug. 2016. Accessed 18 Oct. 2019.