Black/Queer/Intersectional/Abolitionist/Feminist: Essay-ish on the “Deep Sightings” of Black Feminisms during Shock-and-Awe Campaigns of White Supremacy (In Memory of Linda Brodkey)

Black/Queer/Intersectional/Abolitionist/Feminist: Essay-ish on the “Deep Sightings” of Black Feminisms during Shock-and-Awe Campaigns of White Supremacy (In Memory of Linda Brodkey)

Peitho Volume 26 Issue 1, Fall 2023

Author(s): Carmen Kynard

Carmen Kynard is the Lillian Radford Chair in Rhetoric and Composition and Professor of English at Texas Christian University. She interrogates race, Black feminisms, AfroDigital/ Black cultures and languages, and the politics of schooling with an emphasis on composition and literacies studies. Her award-winning book, Vernacular Insurrections: Race, Black Protest, and the New Century in Composition-Literacy Studies, makes Black Freedom a 21st century literacy movement. Her current projects focus on young Black women in college and Black Feminist/Fugitive imaginations in anti-racist pedagogies. Carmen traces her research and teaching at her website, “Education, Liberation, and Black Radical Traditions” (http://carmenkynard.org) which has garnered over 1.8 million hits since its 2012 inception.

Abstract: Part letter, part memoir, and part pissed-off rant, this essay-ish will ruminate on lessons from Toni Cade Bambara’s expression: “deep sight,” a concept shaping her body of work and the title of her posthumously published collection of essays, Deep Sightings and Rescue Missions (1999). In this essay-ish, I examine the specificity of contemporary attacks on Black studies curriculum in relation to Black feminist thought and praxis. Our silence on the specificity of the targeting of Black feminist activism means that no feminist, coalition justice work will be possible for us. I call on Bambara’s “deep sight,” not as a way out or as a way forward, but as an inward-facing pedagogical journey into the “deep sight” of Black feminism that white settler culture is currently attempting to remove.

Tags: Black feminist thought, deep sight, memoir, pedagogy, white settler culturePart examination, part memoir, and part pissed-off elocution, this essay-ish will honor lessons learned from Toni Cade Bambara’s Deep Sightings and Rescue Missions. Bambara imbued her fictional Black characters with “deep sight” into the past, present, and future who avoided simplistic, binary thinking under white settler occupation. “Deep sight” was thus a kind of divining and illumination process, as if ordained by the ancestors and the futures to come, about the most serious threats to the survival of Black peoples. In this essay-ish, I examine contemporary attacks on Black/queer/feminist thought and praxis. I call on Bambara’s “deep sight,” not as a way out or as a way forward, but as an inward-facing political journey into the “deep sight” of Black feminisms into white settler structures.

The current shock and awe campaigns of white supremacy all around us catapult many folx into fear and despair: book bans of everyone not white, not-str8, not middle class, not-able-bodied; full-scale blockades on abortion/reproductive rights; legal suppressions of affirmative action/DEI/CRT; state-sanctioned assaults on immigrants; heightened and state-sponsored homophobia and transphobia; hyper policing and prison re-funding; the Global North’s genocidal campaigns against Palestine; and so much more to come. These shock and awe campaigns of white supremacy are meant to scare and scar us into inaction, meant to make us feel as if what we had before was so radical in comparison to now, meant to make us demand less the next time around, meant to make us forget our own power, meant to confuse us about the rootedness of these oppressions in and for white supremacy, and meant to especially quiet those still new to calling out injustice in loud ways. These campaigns also compel us, however, towards “deep sightings” of our actual convictions, real understandings of white settler culture, true reckonings with a past that never left us, and cyphers of coalition-building that don’t mistake clout-chasing and pick-me-visibility for radical redirections of our world.

This ISH…

I am calling this writing an essay-ish. I am deliberately distinguishing my style, flow, and purpose from the individualistic model of literacy, consciousness, and writing that the white, western essay has always represented (Adorno, Lopate). From essays by Montaigne up to Barthes, form and politics have been deeply rooted in a very specific western, patriarchal, masculinist culture, what Sylvia Wynter calls “Man” who over-represents his local self/reality as all of what counts as human while denying humanity to everything else. For me, the essay is the cultural artifact of “Man’s” expression. Closely linked to “the essay” is the objective science report, that style of dull writing that we see too much of the social sciences (introduction, literature review, methods, findings, conclusions) where you report on an object as an absolutely knowable thing, which is just more of “Man’s” preoccupations and arrogances (Kynard, Lather and St. Pierre). This essay-ish ain’t none of that and is clear on why.

Black queer feminist essay-ish has subverted “Man’s” stylings whether we are talking about the word-work of Audre Lorde or Charlene Carruthers. I link myself to this Black queer feminist break and intervention and call it essay-ish — noun, adjective, and adverb. With the western essay now close to extinction, essay-ish nods to it, yes, but it ain’t tryna replicate, be, and move like it. Essay-ish is politically personal, sassy-attitudinal, coalitional, colloquially rooted in its own here and now, unafraid, Shirley-Chisholm-like in its unbossed and unbought reality, and unapologetically Black.

I am also calling up ish here in the way Black Language uses it as shorthand for shit. As a compositionist, I am laying down on the line that every word, image, and styling that we put on the page, screen, and world are deeply embedded in centuries of power relations. So, yeah, that ish.

Coalition with multiply marginalized communities and histories ain’t possible if we cannot even unthink and unwrite a way away from Man’s expressions (Weheliye). So, yeah, essay-ish.

Red Records

From jump, imagining that our current political targeting is different from the worlds in which we had already lived smacks of a certain kind of white settler forgetting and white liberalist denial (Grande). I began my teaching career as a high school teacher in 1993 in the South Bronx. From 1993-2019, I taught a multitude of high school and college students, predominantly Black and Brown, across Harlem, the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, and Newark. From 2019 to today, I teach at a predominantly white college in an English department where my focus is on the histories of Black education, Black literacy, Black feminist teaching, and Black writing lives; I work in the state of Texas that boasts, amongst many other white supremacies, the most banned books in the country and the ancestral home of Juneteenth. For thirty years now, I have taught about and because of a whole range of Black Freedom dreamers (Kelley). And in those thirty years, my students have come to my classrooms having heard very little, if anything, about the Black folx we read and learn about.

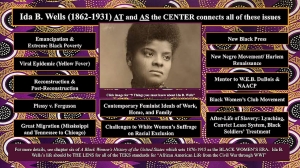

I could give countless examples, but I’ll lay my soul-memory down here in this essay-ish with Ida B. Wells, the activist and journalist most noted for her relentless research and social action against lynching, white feminists’ racism, and racist institutions (Royster). Based on her life and impact at the intersections of emancipation, reconstruction, post-reconstruction, world wars, Yellow Fever, the Great Migration, the New Black Press, the New Negro Movement, Black Women’s Club Movement, Plessy vs. Ferguson, and women’s suffrage, Wells’s life and writing are central to many of the classes that I teach (Berry and Gross). In every class where I bring Ida B. Wells to come sit with us, I always ask the same question: who has heard of Ida B. Wells and what have you learned and read? I’ve had thirty years of silence. I have been teaching non-stop since 1993, upward of at least five thousand students given the heavy teaching loads and large class sizes I have faced in many of my teaching positions—and that does not even include the community literacy programs I have worked in. Without ever a single semester off, I have never met a student in any semester who has known deeply about Ida B. Wells’s life and writing.

In 2020, I did an online workshop for high school teachers about teaching with Ida B. Wells in Texas, because Ida B. Wells is/was part of the Texas content standards. I’ve been in Texas since 2019 where at least 40% of my undergraduate students have attended Texas schools. Ain’t nan one of them heard of Wells and she is IN THE CURRICULUM. I stress this point because you can be IN the curriculum and IN the state standards and still NOT BE IN-CLUDED.

Image 1: Image of a slide and activity from my online workshop for high school teachers on Ida B. Wells. In the background is a patterned design in purple, gold, black, and white, and in the center is a photograph of Wells. Around the photo are black rectangles, each with a topic related to Wells written in white font.

And truth be told, unless I have a graduate student who majored in Black Studies, and sometimes not even then, not even graduate students have read Ida B. Wells’s actual words. A book ban or curricular moratorium on texts that center Black feminists like Ida. B. Wells is, at best, redundant as far as I can see.

I ask students about these learning backgrounds not to shame or judge them, their teachers, or their schools. That’s not my point. Instead, I ask them to really sit with Wells’s impact and ideas and ask themselves why she has been kept hidden from them. I ask students to let her become a new intellectual and political ally to the world they might imagine. This is not about coverage of names and events young people need to know. Though that’s important, you don’t learn about Ida B. Wells to merely memorize her name and historical contributions; you learn about her to develop the audacity and confidence of Black freedom dreaming. What this means for me as a teacher is that I treat any class about the work of the freedom dreams of Black feminist/Black queer folx as an introductory course. It doesn’t matter if it’s sophomores or seniors, high school, college, or PhD students. As far as I am concerned, Black freedom, Black women’s activisms, Black queer critique, and Black feminist creativity have always been banned from schools because my students arrive to my classrooms having experienced none of that. Thirty years and still no one can tell me who Ida B. Wells is even when the state was requiring her! So this next phase of the newest White Supremacist Shock-and-Awe Campaign will look no different than the last 30 years for me.

I want to also add here that support, praise, or acknowledgment of my Black content has also never happened in any institution where I have taught. It feels like every insult and white-passive-aggressive form of sabotage has been hurled my way. The fools I have worked with have never been successful in derailing my teaching convictions and practices, but they are always foolish enough to keep trying. As far as I am concerned, there has never been a moment when my Black content was welcomed by anyone except by my students. And as it ends up, that’s all you really need.

While it will be important to argue and fight back on overt white supremacist setbacks in our current moment, we must know we are fighting for much more. As just one example, DEI on our campuses has never meant radical access and educational transformation as Sara Ahmed has continually shown us. Truth be told, no DEI office where I have ever taught has supported my curricular work. The attacks on DEI must be challenged, yes, but, at the same time, we can’t act like that is the sum-total of our demands for a just education. Book bans on queer, disabled and/or BIPOC authors represent a kind of ethnic cleansing that we must attack endlessly in many ways. However, even when/if the book bans are lifted, curricular justice and equity will not be in our purview (Dumas).

Because I identify as a Black feminist educator, agitator, and dreamer, I understand that transformative classrooms and coalition work require, above all else, imagination. No one today has experienced a western-made institution that regards Black women/ femmes/ gender-expansive folx as fully human and yet we must live and understand ourselves as such anyway. That is the most imaginative work we can ever do. To think and move beyond white settler structures, we’re going to have to think and be creative while the chokehold of our current political climate aims to block radical political imagining by making us fight in small ways and for small things.

The latest removals of Blackness/Black Feminism/Black Queer Critique from our knowledge systems, schools, books, and classrooms are hardly anything new. In fact, our own discipline has actively participated in the day-to-day work of whitewashing, no matter how many position statements are circulated (Prasad and Maraj). Instead of turning towards institutions for redress and repair, I turn to Black feminist ideals of freedom and creative imagination.

The Plagiarism of White Supremacy

I toggle a range of emotions and responses these days. First, there is obvious worry and rage. Behind these performances of moral authority and care for young people is a white supremacist core that is backlashing at our most recent Movements for Black Lives which was more Black feminist and Black queer at its origins than any movement the U.S. has seen (Ransby, Cohen). The current linking of anti-Blackness and anti-queerness in this moment is thus not a coincidence. And it is no coincidence that the states that with the largest influx of a Great Migration BackSouth/BlackSouth are acting the biggest fools. Just like what Ida B. Wells chronicled in her writings, Black Freedom Movements have always been met with a vicious Post-Reconstruction that re-invents violent methods of Black containment (DuBois, Rodriguez). At the close of the 19th century, that meant lynch law segregation (Marable). At the close of the 20th century, that meant the prison industrial complex (Gilmore). What genocidal processes will white supremacy invent again?

Alongside my worry and rage, I gotta be honest: there is also deep boredom for me. I can’t even lie about that. White supremacy is incredibly uncreative and unimaginative. All it seems to do is plagiarize itself and regurgitate its past, failed attempts. If you go back to the banned books of the 1980s in the backlash against Civil Rights Movement gains, you will see the same white supremacist stylings. The names of the authors who were banned in the 1980s, many of whom Judy Blume anthologized, are the same folx banned now. The names on the list of banned books ain’t even new— the list just got rebooted.

I grew up in the Reagan era, first Bush ambush, Tea Party, and so many conservative, super-funded right-wing think tanks that I couldn’t keep up with them. It was a political machine deadset on denying any and all life-chance opportunities to Black peoples, that insisted there were no Civil Rights injustices leftover, that worked day and night to convince us racism was Black people’s own invention cuz white folx were naturally, meritocratically ahead and just. Folx have just plagiarized this mess from the last time. As Black Diaspora freedom fighters from Sylvia Wynter and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o to Walter Rodney always promised though: a colonizing system always produces radicals who slip through its cracks and hack back on all of what the empire so falsely inscribes.

Anti-DEI/CRT-typa legislation surely is not new to Texas, my current home either. We jump-started this 21st century knee-deep in white hostility towards anti-racist rhetoric, literacy, and writing instruction. If there was ever a time to really understand race and the discipline of rhetoric-composition studies, this is it. No one could really be surprised by today’s deployments if they took the time to remember and honor the legacy of Linda Brodkey! As a reminder that I should not have to offer, the white conservative right came for Brodkey’s neck something serious at the University of Texas at Austin in 1990. It is a lesson well worth remembering, because it wasn’t the state, the governor, or conservative students and parents who sold her out: it was the white literary faculty of her English department. Yeah, remember that because the R&B group, TLC, posed a good question that applies to many of yall: what about yo friends? In 1990, Brodkey and a committee of colleagues set out to redesign the first-year writing curriculum to focus on reading and writing critically about difference in the context of anti-discrimination law and discrimination lawsuits buoyed by what I see as Brodkey’s radical feminist consciousness. The language of anti-racism and CRT curriculum wasn’t as readily available to them then, but that is surely what they were tryna create. The majority of the then English department supported the new curriculum; however, a small group of literary faculty went to the ultra-right conservative press and think tanks to complain. Unsurprisingly, it turned into a media storm real fast, what some at the time considered the most visible, public argument that writing studies had encountered. The UT administration tucked its tail between its legs and canceled the curriculum without any regard for the expertise of rhetoric-composition faculty. When I began graduate school in 2000, folx were still very much talking about what “happened in Texas.” Most scholars in the discipline wanted to talk about making sure colleges saw rhet-comp scholars as the ones with expertise in writing instruction and/or debate whether Brodkey and crew handled this moment in rhetorically savvy ways. The fear of Texas was quite palpable. After all, if this is what they did to white feminists, what they gon do to women of color like me? Let’s not kid ourselves here: it took almost thirty years before feminists of color really came back in the numbers that we see today in rhetoric-composition studies in Texas and it’s still entirely too white. And you’d be hard-pressed to find large numbers of white feminists in Texas (or in the discipline) going as hard in the paint as Brodkey did. We would do well not to repeat the mistakes of our discipline’s past by de-racing the history of white-washed rhetoric-composition studies, disremembering actual departmental perpetrators of violence against rhet-comp, pretending as if there is no anti-comp sentiment everywhere we turn, and acting as if there is a rhetorically effective way to persuade white supremacy to be inclusive of the genres of human, as Wynter would call it, that it hates and profiles. We gotta do better than that in the fire this time.

White supremacy never gives us something new. It is never logical. It revolves around lies, distortions, and misdirection. And it always underestimates our resistance.

Stuck Between a Rock and an Even Harder Place

This moment is also a bit like being caught between the proverbial rock and a hard(er) place. On the one hand, we have a reinvigorated and emboldened conservative right whose goal is to shut down anything and anyone who centers histories and ideas that are not white, not-str8, not middle class, not-able-bodied. On the other hand, we have performativity and appropriations of Black feminist activisms that are equally dangerous, violent, and anti-black.

In a recent context, I witnessed support of a job candidate that signaled exactly the kind of violence that performative allyship represents. The candidate was presented, especially to gullible graduate students, as someone with expertise and experience in carceral studies, prison writing studies, abolition, and community literacies. I knew, however, like an old Keith Sweat song, that sumthin sumthin just ain’t right. Here was a white-male-passing PhD graduate in literary studies who had been incarcerated for 4.5 months for felony narcotics distribution, was now a self-proclaimed prison writing educator, and offered no analysis anywhere of racism or their own whiteness. It started with a full pause for me. 4.5 months of jail-time for narcotics distribution and then relatively easy educational access is literally NOT the experience of any Brown or Black person in the U.S., many of whom are still caged away for minor marijuana possessions even in places where cannabis is now legal. At the exact same time that this candidate did a four-month bid, Kalief Browder was an 18-year-old young Black man from the Bronx, NY who was held at Rikers Island jail for three years for allegedly stealing a backpack that no one has seen or been able to confirm to this day. Unable to afford his $3,000 bail, Browder remained at Rikers for three years awaiting trial. He spent almost two of those years in solitary confinement where he was brutally abused and attempted suicide multiple times. Two years after his release, Browder hanged himself at his parents’ home and is now the ancestral catalyst for activism against the prison industrial complex on the East Coast— a hashtag before there were hashtags. Needless to say, my questions about 4.5 months jail time for a white man’s narcotics distribution are not unfounded given the structural racism of the prison system.

And I wasn’t wrong. The candidate got busted with distribution-weight cocaine and pills in a police raid of their apartment in the early 2000s in a large southwest metropolis with a prison system as notoriously corrupt and violent as Rikers Island. Mandatory sentencing in that state was, at the time, five years minimum in federal prison for this felony with a maximum of life in prison (states really only began reducing lifetime sentences for drug-related, non-violent offenses in 2021 when they had no choice but concede this level of sentencing was designed to cage Black and Brown men indefinitely). This candidate didn’t have to face any of that: they got 4.5 months in the county jail (because they couldn’t afford bail) and so faced no sentencing or prison time. That kind of grace and leniency isn’t extended to even white people by the prison system. There is only one way to get that kind of non-sentencing: snitching on everything and everyone, which most surely meant Brown and Black peoples. I don’t mean this as a mere exaggeration, suspicion, or doubt. This is fact. The use of criminal informants is highly concentrated in drug enforcement which is, in turn, highly concentrated in poor, Black communities who have been overexposed to snitching as a central methodology of incarceration (Natapoff). After all, U.S. v. Singleton in 1999, a drug charge case, made it legal to bribe witnesses to secure testimony. The state has a long history of rewarding any eyes and ears for testimony against Black communities. The criminal justice system has used informant/snitches to hyper-criminalize Black urban communities since 1980s Reaganomics and is the residue of COINTELPRO’s protracted targeting of the Black freedom movements of the 1960s and 1970s (Mian). Snitches are a central part of structural racism and the prison industrial complex. Either no one in the department had any direct/personal/familial experiences with the actual prison system, has never listened closely to rap or trap, had no real connections to the most vulnerable Black communities, or they were all acting concertedly to protect the innocence and virtue of the white-passing man in front of us, much like the prison system had.

I looked all through this candidate’s materials for a serious racial analysis and grounding in carceral studies and found nothing. The candidate even went so far as to share incarcerated students’ writing in an online magazine with details describing the contexts of their incarceration. There was no IRB protocol or methodology, even though universities acknowledge incarcerated people as a protected class and do not readily support research about them. The incarcerated folx who the candidate published about could not have legally given their permission to have their writing and sentencings described with such detail in an open, online magazine. In sum, we were co-signing this candidate’s own Tuskegee-esque experiment.

I was further alarmed by this candidate’s outright appropriations of Black feminisms since that alone is making this topic possible for graduate study today. “Carcerality” and “abolition” were never grounded in Black feminist activism at any point. At one point, the candidate even chauvinistically called abolition scholarship solely about “abstraction” and “stats.” To stand in front of a whole-ass room in 2023, after writing a dissertation about prison literature including your own racially-white-anointed 4.5 months in a county jail, call Ruth Gilmore’s work abstract, and reference your own work as effective/narrative/personable is a level of misogynoir that I should never have been subjected to (and this is what I said in my lengthy letter about the candidate, most of which is included here). Even more concerning is that one of the candidate’s publications listed on the CV plagiarized a prominent Black feminist scholar’s book. The candidate did not quote/attribute this scholar anywhere and yet the candidate’s text even mimics the scholar’s title, form, and Black cadence– a text that has wide distribution in prisons, amongst folx who are formerly incarcerated, within work centering Black rhetorics/feminisms/composition studies, and especially for scholar-teachers of community literacies. Hijacking the life-story of a Black woman/professor who has survived sex trafficking and Reagan-era poverty/addiction and doing so for white, personal gain is egregiously violent. The only compositionists who the candidate ever deemed fit to even reference were the lily whitest men of the field. For faculty to think you can just mentor/help all that away is to act as an accomplice to this racism.

When pushed further to discuss abolition, the candidate offered his pedagogy of teaching writing in prison to “them” as the penultimate way to end the entire prison industrial complex and free all these Brown and Black folx from prisons. You can’t do anything but feel sorry for the graduate students who believed this was someone with expertise in community literacies, when literally everything this candidate had to say about the politics of teaching and writing has been challenged for decades in our discipline. Even at our worst, rhet-comp folx do not co-sign white-passing men’s convictions that they alone can unravel an entire prison industrial complex rooted in plantation logics (McKittrick) with the wonders of their approach to writing instruction. I mean, really. You don’t even need fiction when real life is this outrageous: thief Black women’s work to commit to ongoing anti-black racial violence.

“It’s Got To be Real”

So here we are. State-sanctioned violent actors can target abolitionism and radical feminisms in our classrooms with impunity; and at the exact same time, academics can appropriate Black feminist activisms to sustain their anti-blackness and call themselves the most radical answer to social, educational inequity.

For sure, our schools are under siege. But wasn’t nothing deeply transformative happening in those schools before. They have been hell-bent on maintaining institutional whiteness even without a conservative bogey-man to call up.

When it all falls down, I still have faith and energy. There was that brief moment circa 2020 when George Floyd was murdered during the pandemic and a performative version of anti-racism swept up the nation. Thankfully, actually, those empty gestures are now gone. Those same people who adorned anti-racist and anti-colonial pedagogies like a new fashion statement ain’t ready for the real risk-taking that kind of work has always entailed. In the words of Cheryl Lynn, it’s got to be real! The rest of us will withstand the backlash because we were risking our lives all along anyway. In our coalitions, we need to remind ourselves that we belong to longstanding traditions of creating spaces and practices that exist beyond— way way way beyond— the current ordering of things and its utter inability to ever contain us.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor. “The Essay as Form.” New German Critique, no. 32, 1984, pp. 151-171.

Ahmed, Sara. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Duke UP, 2012.

Bambara, Toni Cade. Deep Sightings and Rescue Missions: Fiction, Essays, and Conversations. Pantheon, 1996.

Berry, Daina Ramey and Kali Gross. A Black Women’s History of the United States. Penguin Random House, 2020.

Blume, Judy. Places I Never Meant To Be: Original Stories by Censored Writers. Simon and Schuster, 1999.

Brodkey, Linda. “Making a Federal Case Out of Difference: The Politics of Pedagogy, Publicity, and Postponement.” Writing Theory and Critical Theory, edited by John Clifford and John Schilb, MLA, 1994, pp. 236-261.

Carruthers, Charlene. Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements. Beacon Press, 2019.

Cohen, Cathy and Sarah J. Jackson. “Ask a Feminist: A Conversation with Cathy J. Cohen on Black Lives Matter, Feminism, and Contemporary Activism.” Signs, vol. 41, no. 4, 2016, pp. 775–792.

Dillon, Stephen. “ ‘I Must Become a Menace to My Enemies’: Black Feminism, Vengeance, and the Futures of Abolition.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 28, no. 2, April 2022, pp. 185-205.

DuBois, W. E. B. Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880. Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1935.

Dumas, Michael. “Beginning and Ending with Black Suffering: A Meditation on and against Racial Justice in Education.” Toward What Justice?: Describing Diverse Dreams of Justice in Education, edited by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, Routledge, 2018, pp. 29-45.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. University of California Press, 2007.

Grande, Sandy. “Refusing the University.” Toward What Justice?: Describing Diverse Dreams of Justice in Education, edited by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, Routledge, 2018, pp. 47-65.

Kelley, Robin. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Beacon Press, 2002.

King, Tiffany L. “New World Grammars: The ‘Unthought’ Black Discourses of Conquest.” Theory & Event, vol. 19 no. 4, 2016.

Kynard, Carmen. “‘Oh No She Did NOT Bring Her Ass Up in Here with That!’ Racial Memory, Radical Reparative Justice, and Black Feminist Pedagogical Futures.” College English, vol. 85, no. 4, 2023, pp. 318-345.

Lather, Patti and Elizabeth St. Pierre. “Post Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 26, no. 6, 2013, pp. 629-633.

Lopate, Phillip. The Art of the Personal Essay: An Anthology from the Classical Era to the Present. First Anchor Books, 1995.

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider. Crossing Press, 1984.

Marable, Manning. How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America: Problems in Race, Political Economy, and Society. South End Press, 1983.

McKittrick, Katherine. “Plantation Futures.” Small Axe, vol. 17 no. 3, 2013, p. 1-15.

Mian, Zahra N. ““Black Identity Extremist” or Black Dissident?: How United States V. Daniels Illustrates FBI Criminalization of Black Dissent of Law Enforcement, from Cointelpro to Black Lives Matter.” Rutgers Race and the Law Review, vol. 21, no. 1, 2020, pp. 53-92.

Natapoff, Alexandra. Snitching: Criminal Informants and the Erosion of American Justice. NYU Press, 2010.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Heinemann Educational, 1986.

Painter, Nell. Soul Murder and Slavery. Baylor University Press, 1995.

Prasad, Pritha and Louis M. Maraj. “‘I Am Not Your Teaching Moment’: The Benevolent Gaslight and Epistemic Violence.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 74, no. 2, 2022, pp. 322-351.

Ransby, Barbara. Making All Black Lives Matter: Reimagining Freedom in the Twenty-First Century. University of California Press, 2018.

Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications, 1973.

Rodriguez, Dylan. “Another Moment in the Long History of White Reconstruction.” The Real News Network, 28 Aug. 2017, https://therealnews.com/drodriguez0824white

Royster, Jacqueline Jones. Traces of A Stream: Literacy and Social Change Among African American Women. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000.

Weheliye, Alex. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Duke UP, 2014.

Wells, Ida B. (1894) The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States.Donohue & Henneberry, 1895.

—. Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. New York Age Print, 1892.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation–An Argument. CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 3, no. 3, Fall 2003, pp. 257-337.

PDF

PDF