Feminist Resistance, Resilience, and Concession: Historical Moments of Activism by NCTE and CCCC Feminist Groups (or, “Whatever You, Betty, and Nancy Think Ought to Be Done”)

Feminist Resistance, Resilience, and Concession: Historical Moments of Activism by NCTE and CCCC Feminist Groups (or, “Whatever You, Betty, and Nancy Think Ought to Be Done”)

Peitho Volume 26 Issue 1, Fall 2023

Author(s): Holly Hassel and Kate Pantelides

Holly Hassel teaches and researches in writing pedagogy, writing program administration, and assessment. She has been on the faculty at University of Wisconsin-Marathon County, North Dakota State University, and is currently Professor in the Department of the Humanities at Michigan Technological University. Her most recent book project is A Faculty Guidebook for Effective Shared Governance and Service in Higher Education (Routledge, 2023), with Kirsti Cole and Joanne Baird Giordano. She has previously served as chair of CCCC and editor of Teaching English in the Two-Year College. She can be reached at hjhassel@mtu.edu.

Kate Pantelides is an associate professor of English at Middle Tennessee State University, where she teaches composition and rhetoric courses to students of all levels. Her research addresses feminist rhetorics and writing research methods. Her recent textbook, Try This: Research Methods For Writers, co-authored with Jennifer Clary-Lemon and Derek Mueller, is freely available digitally. She can be reached at kate.pantelides@mtsu.edu

Abstract: This article traces three specific moments of coalition building throughout the last five decades of feminist work within NCTE and CCCC: establishing a group focused on gender equity in CCCC, drafting and implementing the NCTE Guidelines for Nonsexist Use of Language, and establishing resources for childcare at the annual CCCC convention. Demonstrated through an array of documents from the NCTE archives, these key moments highlight strategies and barriers to feminist movement. Feminist advocacy in this work ranges from stealth advocacy, to rewriting the sexist rules of the organization, to adhering to the protocol set forth in order to effect change. Analysis of these key moments provides insight for disciplinary reflection and accountability as well as a variety of advocacy strategies for future coalition building.

Tags: child care, Committee, kairotic moment, sexist language, stealth advocacyTwenty-twenty-three has been a rather momentous year for American feminist histories. We just fell short of the 50th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, although Ms. magazine was able to celebrate its 50th birthday, and along with that the many changes to both the material lives of women and evolving perspectives on women’s social roles that the magazine has chronicled. In the field of Writing Studies, we passed the 50th anniversary of the creation of what became the Conference on College Composition and Communication’s (CCCC) Feminist Caucus, and we’re nearing the 50th anniversary of the landmark passage of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) Guidelines for Nonsexist Use of Language (now known as the Statement on Gender and Language).

Since our recent disciplinary feminist history is middle aged, it is perhaps feeling the same things American women are often invited to feel at middle age: less visible, less cool, less spry than we once were, inviting some familiar questions: Where have we gotten? How did it happen? Who made it happen? Where should we go from here? In parallel, the coauthors, as former co-chairs of the CCCC Feminist Caucus, also seek to make sense of our “affective inheritance” (Ahmed), do the “difficult work” of “acknowledging [our feminist] history” (CFP) and thus, continue coalition building within the field, learning from both our successes and missteps.

We draw from NCTE/CCCC organizational documents spanning from the 1960s to the present several key moments of solidarity and feminist effort within the organization to identify some of the real and manufactured barriers to achieving feminist movement. We focus on three key events and their attendant processes: the creation of the CCCC committee on the Status of Women in the Profession itself, the development of the Guidelines for the Nonsexist Use of Language in NCTE Publications, and the ongoing effort to offer onsite childcare at the conference. Each action utilizes similar coalition building tools, but ultimately, they demonstrate the continuum of feminist advocacy strategies, ranging from stealth advocacy, to rewriting the sexist rules of the organization, to adhering to the strict rules set forth in order to effect change. We show through these historical events and artifacts how organizational processes and individual resistance created barriers to moving feminist work forward. We identify some of the common strategies (rhetorical and logistical) deployed by those with decision-making authority used to resist inclusive practices and policies. In tracing these barriers and strategies, we aim to offer insight to feminist practitioners in the field doing both disciplinary and outward-focused justice work, insight that provides both an opportunity for disciplinary reflection and accountability as well as a variety of advocacy strategies for future work.

Event 1: Forming a CCCC Committee on Status of Women in the Profession

The first of our three examples of feminist advocacy strategies stems from the creation of the NCTE and CCCC committees focused on women, exemplary disciplinary coalition building. NCTE was inspired perhaps by the Modern Language Association’s (MLA) committee on women, charged in their December 1968 meeting. NCTE followed suit in 1970, asking Barbara Friedberg, Kay Hearn, and Virginia Read to develop a Committee on Women, which was constituted officially as the NCTE Committee on the Role and Image of Women in the Council and the Profession (just rolls off the tongue). Their early work included gathering quantitative data about women’s involvement in the organization, counting how many women were represented as presidents, members, award winners, and other recognized positions within the organization.

Janet Emig was charged in November 16, 1971 as chair of the NCTE committee (Full charge, Appendix A, 1971 NCTE EC). In his letter of invitation to Emig, NCTE Executive Director Bob Hogan suggested, “You might […] want to begin thinking of the group’s focus. Is it to deal only with the college, where most of the inequity seems to be, or does the public school woman teacher need to have a means of expression and a hope of redress?” (2). The initial language here suggests that though the group’s work took place through NCTE, even the initial charge focused heavily if not primarily on college English teachers, underscored by the appointment of Professor Emig as the chair.

College faculty spearheaded much of the work of the early NCTE committee, and it seemed natural that an effort to establish a similar group specifically within CCCC would emerge. However, the establishment of such a group required significant bureaucratic and administrative effort, much of which was stymied by Hogan. The negotiation over the formal charging of the CCCC committee illustrates some principles of what we call “stealth advocacy” deployed, in particular, by two figures in the archives, Betty Renshaw (CCCC secretary at the time of the committee formation and a professor of English at Prince George’s Community College), and Nancy Prichard (NCTE staff liaison to the CCCC Executive Committee and Associate Executive Secretary of NCTE). Of course, as is the case with most feminist advocacy, many people were involved in the development of the committee, but Renshaw and Prichard played a particularly satisfying role.

The archival record suggests that specific requests to form a CCCC committee started in earnest in the late 70s, with Lou Kelly, revolutionary University of Iowa Writing Lab Director and early leader and member of the NCTE Women’s Committee, directly asking “Jix,” 1977 CCCC Chair Richard Lloyd-Jones, to charge the group. She reasoned that there was more work than was possible for one committee, and that the NCTE committee had been doing much of their work for CCCC. It only made sense to have a committee focused on the needs of CCCC constituents within the organization. Yet, there was reluctance by some members to have more than one committee focused on the needs of women. In fact, once the committee was voted into existence, Bob Hogan shared his specific concerns with Lou Kelly. He wrote:

One thing I don’t like about myself is that I put off doing the things I feel uncomfortable doing. But, damn them, they just won’t go away. So I’m taking up one of them in this letter…Although the officers of CCCC did authorize in principle the formation of a women’s committee under the aegis of CCCC, that’s all they did. Had I been alert during that part of the officer’s meeting, I would have asked for a delay. But what I thought was merely a report of a request relayed through Betty Renshaw, turned out, in Betty’s and Nancy’s notes, as a formal motion, seconded, and carried.

The letter details Hogan’s opposition to the formation of a “Woman’s Committee” in CCCC, which he characterizes as “a call for volunteers without any battle plan,” a “duplication of effort,” and lacking both financial and staff support. Despite these concerns, the CCCC committee was formed (June 21, 1977, “Letter to Lou Kelly”). We excerpt the letter at length in part because it’s rare that people use falling asleep in a meeting as an excuse to explain their disagreement (“Had I been alert during that part of the officer’s meeting, I would have asked for a delay”) but also because we are inspired by Renshaw and Prichard’s stealth feminist advocacy, which captures the spirit of the moment in the archive, a moment when women’s committees in NCTE, MLA, and, finally, CCCC were organizing and pushing for greater representation within English Studies.

In full (see Appendix B) Hogan’s letter typifies bureaucratic forms of resistance deployed to stall organizational change work, and his honesty about his desire to stymie Betty’s and Nancy’s[1] work is instructive for the committee history that follows. In just this brief excerpt Hogan openly admits that he didn’t pay much attention to Betty and Nancy, and had he been aware of them, he would have used his power to “delay” and ultimately subvert their efforts. But like many feminist stalwarts across the years, “damn them, they just won’t go away.” This latter bureaucratic strategy is particularly effective in spaces where progressive advocates are in the minority. We saw this recently in the Tennessee and Montana legislatures, where minority, progressive representatives were expelled and silenced because the rules allowed such action. Why argue with your opponents when you can just ignore them?

What stands out to us in Hogan’s appeal to bureaucratic convention is the contradiction that the bureaucracy was apparently in place (the officers did authorize in principle the formation of a women’s committee under the aegis of CCCC), yet Hogan simultaneously suggests that the protocols were not followed. From a rhetorical/tactical perspective, Hogan essentially wants to have his cake and eat it too: rules were followed, but he wasn’t following. Hogan further appeals to Lou Kelly’s sense of wise stewardship, writing that the NCTE is now “disciplined” with its budget and discontinuing a practice of approving expenses incurred without prior approval. He asserts that “at this point there is no money to spend,” which is intended to derail the group’s request to convene and distribute a newsletter. This appeal to efficiency is further discussed when Hogan suggests that the CCCC-specific group would be a “duplication of effort,” connecting again to the idea of resource constraints.

Like many rhetors committed to maintaining the status quo in the face of calls for change, Hogan invokes in his letter an ethos of benevolence and protection for women in his employ and for the women making the appeal themselves. In particular, he cites the problem of staff support, noting that “Linda Reed works for the NCTE committee out of her own commitment and good will, and largely on her free time […] A full-time job, a husband, three children, liaison responsibilities for one NCTE committee, and nurturing her own spirit may be enough of a load” without adding to that support of the CCCC Committee, appealing to the readers’ presumed desire not to impinge on the time and labor of (another) woman staff member. In this way Hogan effectively demonstrates the difference between support and solidarity. By paternalistically framing Linda Reed’s “support role,” and his actions as protective of her time, he is able to prevent her from supporting feminist solidarity work, work that ultimately changed the working lives of women in the discipline rather than only drawing on their support.

Despite Hogan’s numerous concerns, Renshaw and Prichard persisted, using pronoia – “tactical foresight” or long-term strategic thinking to set up future kairos (Mueller et al.) – when they saw their opening to formalize the group. They used their “subordinate” roles as secretaries to create space for feminist advocacy. They took a leap of faith. And because Robert Hogan was snoozing, it worked. Another way to frame Betty and Nancy’s work is in terms of stealth advocacy, enacting change through the tools of bureaucracy: meeting notes, the limited tools at their disposal. In subsequent communication about the creation of the committee, Jix writes to Beverly Henegan of Renshaw’s power: “Betty’s letter makes it clear that I was supposed to appoint you to whatever you, Betty, and Nancy think ought to be done. I’d be more specific, but Betty is the one who says what we decide…If Betty tries to make any evasive actions about what she can’t do by claiming she is just the secretary, you are free to point out that I took even her indirect suggestion as an order.” In such work advocacy might not always appear as such. It might just, as in this key feminist moment, manifest as meeting notes, declaring the existence of a new coalition. Feminist histories are often humble histories. Subsequently, feminist change might not be immediately recognizable, and will likely not be written up in a press release. It may take the form of microactivist strategies, tools for feminist invention in spaces particularly resistant to change.

Event 2: The 1975 Guidelines for Nonsexist Use of Language in NCTE Publications

The second example we draw attention to is the development of the 1975 Guidelines for Nonsexist Use of Language in NCTE Publications (referred to throughout as Guidelines) for the reason that it illustrates quite different sets of strategies and advocacy used by the NCTE Women’s Committee to write, gain approval for, and implement this set of guidelines. The 1974 NCTE convention included a resolution to create such a document, and the November 1975 Board of Directors meeting at the convention in San Diego included the decision for NCTE to “encourage the use of nonsexist language, particularly through its publications and periodicals” (page 1, Guidelines). Just four years after the NCTE Committee on the Role and Image of Women in the Profession was formally charged, they, along with the NCTE Editorial Board, authored the Guidelines. Although the direct audience for the Guidelines was editors such that they could ensure their publications adhered to the discipline’s preferred language conventions, the authors note that “eliminating sexist language can be useful to all educators who help shape the language patterns and language usage of students and thus can help promote language that opens rather than closes possibilities to women and men.” The Guidelines content includes examples of problematic, sexist language and presents different methods for revising them using nonsexist language alternatives.

Though the Guidelines themselves were seemingly approved at the NCTE Executive and Board of Directors levels with minimal fuss, operationalizing the Guidelines was another matter. This process gave rise to a series of complicated tensions and resistance, with mixed reactions from members and extraordinarily hostile responses from some well-known leaders in the field. What we want to illustrate in this section are some of those tensions that emerged and the strategies that the NCTE Women’s committee used to push back in public, assertive ways. From the start, there was a concern with whether and how to identify sexist language, and with what tone sexist language should be addressed. Committee member Marilyn McCaffrey’s letter (29 Sept. 1975) congratulating Linda Reed and Susan Drake on the Guidelines exemplifies such conflict: “It is clear and thorough and the tone is one of reason rather than militancy. All of this pleases me.” At nearly that same time (9-30-1975) Ed Corbett[2], then the editor of College Composition and Communication and, at that time, member of the CCCC officers team, wrote a strongly contrasting letter to the authors detailing extensive objections to the Guidelines:

Right from the beginning, I have not been in sympathy with the movement to neuterize gender in our language. The Women’s Liberation movement has fought some good fights on important issues–equal job opportunities, equal pay for equal work, etc–and I am wholeheartedly behind them in those fights. But when women’s groups charge that terms like chairman are discriminatory, I can only conclude that some of the women in the movement have lost sight of the important issues and are wasting their energies on trivia.[…]

Let me say that one of the most sensible statements on this matter is Murel R. Schulz’s “How Serious Is Sex Bias in Language,” which I published in the May 1975 issue of CCC.

Like Mr Milquetoast, I’ll probably buckle under to these Guidelines if they are officially adopted by NCTE for its publications, but I will be a disgruntled male chauvinist all the while I am kowtowing.

In the Schultz article to which Corbett effectively lays claim in his letter, she writes of the myriad problems of adopting congressperson and chairperson in lieu of congressman and chairman, as the Guidelines suggest, “[A] difficulty with -person is that men resist accepting the new label. Why should they accept the neutral term chairperson? Chairman, statesman, congressman, and workman have served long and well. Why should these terms be obliterated by feminine decree?…The problem of pronouns stubbornly resists solution. The use of the generic he reflects the fact that our language is male-oriented” (164). Schulz suggests also that “person” means “woman,” since “man” is the obvious default, and discounts the possibility of “sex-free pronouns” gaining traction, though she does note the use of “they/them” as a useful possibility. Schulz’s prescient words typify the reluctance to adopt nonsexist guidelines for publication. Since men have power, she suggests, and language reflects that power, there is no impetus for men to relinquish any of their power. Schulz makes this observation without recommendations to address the imbalance, instead rightly noting that language reflects society and is difficult to change, particularly for those in the dominant majority. In other words, a resistance strategy on the part of those invested in the status quo, such as Corbett, can include co-opting the voices of members of marginalized groups to support the dominant stance. Given Corbett’s reluctance to “neuterize” language, it is little surprise that he was happy to publish Schulz’s argument and indirectly claim responsibility for her work. Certainly as one of the most influential and powerful members of the field at the time, the objection from Corbett would have been impactful.

The Committee was interested not just in having guidelines but in thinking about how to operationalize them; they used a variety of direct activist strategies to institutionalize the guidelines and ensure that they were, despite Corbett’s objections, “officially adopted by NCTE for its publications.” For example, the Committee issued a call for manuscripts, noting “A CCCC resolution directed a task force to prepare materials to aid college teachers in implementing the NCTE resolution on Sexist Language” (appears in October 1977 issue of CCC, p. 256, and was also noted November issue of College English that same year). They also offered a “service” to NCTE publications, providing feedback on their relative success implementing the Guidelines. You can imagine the popularity of this effort: everyone loves being told that they’re sexist and how to change that.

Even once the guidelines were officially adopted and implemented, there were concerted efforts to subvert the change. In particular, in 1978 at the end of the NCTE Annual Business Meeting in Kansas City, Missouri, Harold Allen presented a sense-of-the-house motion endorsed by the Commission on Language to weaken the Guidelines, such “that the policy opposing the use of sexist language in NCTE publications shall not be so construed as to prevent the use of such language by an author if the accompanying editorial comment indicates its presence is the result of an author’s express stipulation.” Although this first motion failed, a subsequent motion the following year passed, though we’re not aware of anyone availing themselves of the opportunity to mark their work as purposely sexist in NCTE publications (we aren’t able to address this fascinating negotiation in the depth it deserves here, but please stay tuned).

Despite the pointed critiques and reluctance by some powerful members of the discipline, the Guidelines were written and shared by 1975, and implemented and adopted with just the one amendment by 1979. In contrast with the development of the Committee on Women itself, which required stealth advocacy and decades of requests before officially being charged within CCCC, the work of the Guidelines was completed on a startlingly fast timeline and with direct advocacy. Further, the work of the Committee extended beyond its immediate members and significantly changed the workings of NCTE writ large. The far reach and its lasting impact are characterized by their continued mention in each NCTE and affiliate conference program, and the multiple revisions to the document that have helped it reflect current language practice. Instead of remaining a distinct aspect of NCTE, relegated to “women’s work,” the Guidelines were adopted within the organization itself and officially taken up by leadership.

Event 3: The Movement for On-Site Childcare at the CCCC

The implementation of the Guidelines was hard won, representative of the discursive “role and image” of women in the profession. Our third key moment, however, addresses another priority of the Women’s Committee, the presence of women in the discipline, and, in particular, at the convention. In 1978 during the Women’s Exchange at the CCCC Convention, Ginny Kirsch is credited in a newsletter with asking “Do motherhood and rhetoric mix”? The emphatic response from various iterations of the committee[3] has been to try to make parenting and active participation in the discipline more possible. Certainly since the CCCC Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession (CSWP) was officially constituted in 1983, one of its primary purposes was “to continue to promote the participation of women in the annual convention, on CCCC committees, and in positions of leadership within CCCC,” and while of course not all women are or want to be mothers, it is well documented that being a mother and an academic often conflicts (Gabor, Neeley, Leverenz; Sallee; Ghodsee and Connelly; Mason, Wolfinger, and Goulden; Siegel; Slaughter; Sallee). Targeting childcare support was identified early on as an important strategy to support the aim of increasing women’s representation at the convention. In fact, one of the nine charges put forth for the 1971 NCTE Committee on the Role of Women in the Profession and the Council, a progenitor of the Feminist Caucus, included “responsibility to focus its attention on” “sources or lack of sources available for child day care so that women with children can successfully pursue graduate study and/or half- or full-time teaching” (Appendix A).

Despite this immediate focus and the fact that childcare was regularly requested as a need in yearly reports, it was decades before childcare was formally offered at the convention, and then only for a brief time (2009-2010). In 1988, the CSWP asked the EC for financial support – $50-100 – to research the need for and feasibility of offering daycare at future CCCC conventions. They requested polling members in the exhibit hall or including a question about childcare needs on a “ballot going out to members at officer election time.” In 1990, the CSWP submitted a formal memo requesting that the EC “institute childcare facilities at its annual convention on a three-year pilot basis to begin in 1991” (Childcare at the CCCC Conventions memo, April 17,1990). Yet, the EC responded that after having polled the membership, they learned that only 5% of conference participants would take advantage of childcare at the convention should it be offered. They “concluded that, given what seemed to be a need among a relatively small percentage of the membership, it would not pursue the issue further at this time” (Response to CSWP from EC). Of course, the CSWP did not agree with the EC’s finding, calling the decision “troubling” and arguing that they “consider providing childcare facilities for the children of parents (both men and women among our membership) who participate in our conference to be an ethical commitment, not a luxury.” The flaw of these data, of course, is survivorship and/or sample bias. That is, it’s quite possible that members with children had simply disengaged from professional activities of this kind in order to balance the demands of mothering with the professional obligations that participation in the CCCC convention created.

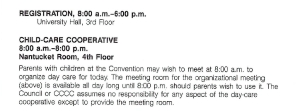

Although the EC did not provide a budget for childcare following the formal request, they did allot space for parents at the following convention in 1991, specifying that “CCCC assumes no responsibility for any aspect of the day-care cooperative except to provide the meeting room.” The Child-Care Cooperative invited participants to use the room as needed and meet in the morning to organize care for the day together (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: 1991 Convention Program Information about the Childcare Cooperative. Image description: screenshot of archival conference program giving the hours and location of the Child-Care Cooperative: 8am-8pm, Nantucket Room, 4th Floor.

In 2004, the CSWP report cites “concerns related to maternity” as a primary focus of the committee and again requests that the EC prioritize childcare at the conference. In response to these repeated requests, the ad hoc Committee on Child Care Initiatives was formed following the November 2007 meeting of the Executive Committee. They were charged to explore child care options in New Orleans and for four subsequent conventions. As the newly appointed chair of the CSWP, Eileen Schell was a member of the CCCC Committee on Childcare Initiatives, chaired by Susan Miller Cochran. Members of the committee also included Rosalyn Collings Eves, Roger Graves, Sue Hum, Gerald Nelms, and Blake Scott.

The Childcare Committee did extensive research and advocacy toward the goal of offering childcare at CCCC. They had four research priorities: researching childcare in New Orleans, articulating the “the pros/cons of pursuing an informal option in New Orleans,” identifying peer organizations’ practices, and considering liability (Susan Miller Cochran committee communication). They found that many other organizations offer childcare, often through KiddieCorps (who provided onsite childcare at MLA 2007) or Accent on Children’s Arrangements (who ultimately provided onsite childcare at CCCC 2009), commercial service groups that offer childcare for specific events such as conferences. Other iterations that surfaced in their research included babysitting co-ops organized by conference participants, recommendations for local childcare options provided through the convention center/hotel, and vouchers meant to offset the cost of childcare. A 2007 Chronicle article entitled, “Bring the Kids,” detailed one such approach by the Association for Jewish Studies that offered childcare for $40/day for all interested faculty at their annual meeting. Perhaps the strangest option that arose in their research, and one that is indicative of the many hoops participants must often jump through to receive “help,” was from a Linguistics Conference, LSA (January 2008), that provided the following stipulations for parents to receive a Childcare Referral or Stipend:

(1) They are presenters on the LSA program. (2) The caregiver they secure is a graduate student or unemployed linguist.[4] [This person will also receive a complimentary Annual Meeting registration.] (3) The caregiver has agreed to provide child care for no more than two children for 8-12 hours. (4) The parents notify the Secretariat no later than 1 November 2007”.

Although the intention of the requirement that childcare stipends go to “unemployed linguists” is understandable, one has to wonder how many busy parents were able to take advantage of such a narrow requirement or were comfortable approaching graduate students to make such a (inappropriate?) request. Liability was a consistent concern that came up in conversations about childcare, particularly in such informal iterations, but the two large organizations had liability insurance to cover both themselves and the organization, making this the most expensive, but most appealing option.

Given the reality of the convention calendar in which funds and space are allotted so far in the future, it wasn’t possible to get childcare up and running for the convention until 2009 in San Francisco. Ultimately, there seemed to be support on all sides for the work of the committee and the fact of childcare at the convention in the future (See Appendix C for relevant information distributed by the group to stakeholders and report information submitted to the CCCC officers, notably that a professional service was contracted and a childcare collective was created). Thus, childcare options were offered for the New Orleans convention, just not the on-site childcare option that the committee identified as necessary for effective inclusion of parents in the convention. We don’t have documentation of how many parents participated in the informal options offered in New Orleans, but “Bring the Kids,” as well as the extensive research by the Committee on Childcare Initiatives demonstrates that informal babysitting among conference members and individual sitters in guest hotel rooms are not preferred by most parents.

Spurred on by their work toward the 2008 New Orleans convention, in their Report to the CCCC EC, the Committee on Childcare Initiatives resolved that there would be formal onsite childcare at the 2009 San Francisco convention calling for further solidarity regarding the CCCC initiatives around childcare (see Appendix D for the full motion), resolving that: “the Conference on College Composition and Communication contract with a professional childcare provider to provide childcare at the 2009 CCCC convention and beyond. Further, we urge that this service be provided at a subsidized rate for graduate students and contingent faculty” (March 18,2008 Committee Report to the EC). They were committed to getting a jump on the convention calendar and ensuring necessary space and effective communication. A significant part of the committee’s work leading up to the 2009 convention itself was making the childcare option visible. There were numerous concerns that the opportunity wasn’t made clear to registrants, which would preclude them from taking advantage of the service in San Francisco. The committee was understandably concerned that if the service wasn’t made use of, it would be hard to build momentum for the long term on-site childcare solutions they were working toward. They had much to contend with. In addition to identifying a reliable, safe provider and communicating the available service on a tight timeline, they had to work against the perceived “prevailing attitude/assumption […] that people were not supposed to bring their kids to professional meetings” (Roger Graves, personal communication, 2023). Roger Graves, a member of the Committee on Childcare Initiatives, describes how he and his wife, like other academic partners, alternated caring for children and attending sessions, or taking turns going to the convention each year.

Finally, at the 2009 San Francisco convention, Camp CCCC came to fruition. The Committee Chair, Susan Miller-Cochran, announced the options, which were also included in less detail in the program:

This year we are offering an on-site activity center for childcare, Camp CCCC, during the convention from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. Thursday through Saturday right in the Hilton Hotel. Children ages 6 months to 12 years old are welcome. The center, staffed by experienced CPR and Pediatric First Aid certified professionals, will provide age-appropriate entertaining and educational activities, including storytelling, hands-on crafts, games, the “Build It Zone,” and the “Boogie It Zone.” Infant care stations, rest areas, and “SecurChild®” photo check-in and check-out will ensure a safe, secure environment.

The San Francisco Childcare Pilot was a success, noted in both the yearly reports for the Committee on Childcare Initiatives and the CSWP, whose members and work necessarily overlapped. CCCC allotted $3000 to offset participant childcare costs. Fourteen families used the services, all of whom unanimously said that the existence of childcare at the conference enabled them to participate. Still, the childcare option wasn’t very visible, and, though they didn’t track a waiting list, the provider noted that at least ten parents visited the childcare center and noted that they would take advantage of the service at the following convention since they didn’t become aware of the it until they were at the convention. The Committee on Childcare Initiatives asked that the EC fund childcare at $4,640, the amount “needed to hire professional providers for on-site care” (2009 email from Eileen Schell regarding childcare), beyond the $3000 they had agreed to. Cengage sponsored the initiative with a $1500 donation, and both the Childcare committee, CSWP, and the EC suggested that external sponsors of childcare might be a useful direction for long term support of the service. The 2010 Convention in Louisville again offered onsite childcare through Accent on Children’s Arrangements.

Unfortunately, CCCC’s commitment to supporting childcare for at least four years at the convention (usage of which very likely may have increased over time as awareness grew) changed. Though the exact set of decisions that led to the evaporation of childcare options is unclear, several motions from relevant EC meeting minutes suggest a few explanations. First, in March 2009, a “crisis” emerged in which dozens of manuscripts were accepted to CCC without sufficient page allotment to publish them, requiring the reallocation of a significant amount of funding, upon a vote by the EC, to cover the cost of publication and expansion into CCC online. Though it appears funds were preserved for the 2010 convention, a review of CCCC EC minutes from November 2009, March 2010, and November 2010, along with the Childcare Committee’s two reports that same year, suggest that somewhere during that 2010 time period, no funding was actually preserved for supporting childcare efforts at the convention. A Sense of the House motion in support of subsidized childcare did pass at the convention in 2010. However, there is no formal documentation that the Childcare Committee’s request for 2011 funding was ever acted on by the EC.

The perfect storm of relatively low participation in the childcare service given its newness, the journal’s fiscal crisis, and somewhat misleading responses to CCC’s survey of members about the need for childcare (the survey asked who would take advantage of on-site childcare without asking if the member needed childcare at all), resulted in an early end to the pilot. In rejecting the committee’s funding request for professional, on-site childcare, Program Chair Marilyn Valentino instead recommended working with the “the local arrangements committee to find suitable, safe, and reliable services close to the convention site, perhaps through a university’s childcare service or similar venue.” Yet, in the June 7, 2010 Committee on Childcare Initiatives Report, they underscored the importance of on-site childcare in lieu of other options, noting that its purpose,

…is to help make childcare more safe and reliable, and less of a burden, to members who require this service in order to attend the convention. While we realize that childcare is not an immediate concern of every member of CCCC, we believe that providing this service sends an undeniable message about who is welcome in our organization, how inclusive we are, and how much we value the diversity of membership that such a service supports. CCCC will need to continue to commit to a long-term childcare solution for future conventions. Our concern for the well-being of contingent faculty, junior faculty, and graduate students, and our desire to be as inclusive as we possibly can, demand that we address this issue consistently.”

Despite this rebuke, the Childcare Committee concluded its three year existence, was not reconstituted, and on-site childcare was not offered again at the convention after 2010. Although rooms continued to be provided for nursing parents, space for a childcare Co-op was not allotted, nor was the babysitting swap continued. It is perhaps telling that the Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession was reconstituted from 1983-2015, suggesting that the work of this committee was not finished, yet the Childcare Committee only existed for its three-year term. Subsequently, the requests for childcare once again returned to the CSWP’s report requests, unheeded as they were for the previous two decades.

In 2015, the CSWP again proposed an academic day camp at CCCC, which was not funded; however, the EC provided support for new Childcare Grants, $300 each/10 grants, the same original budget that had been allowed to lapse four years earlier. Concurrently, the CSWP helped distribute information on the new SIG Academic Mothers, another indicator of the continuing relevance of Ginny Kirsch’s 1978 question, “Do motherhood and rhetoric mix”? Since then, the Childcare Grants have been renamed Care Grants, and they are offered to any dependent caregiver. In keeping with the committee’s original, consistent priorities, graduate students and contingent faculty are given preference if the allotted funds run out. MLA, which also at one time offered onsite childcare, has moved to a similar voucher program in which conference registrants can submit childcare receipts up to $400. Preference is also given to graduate students and contingent faculty. Like many changes to higher education, childcare vouchers offer individual support rather than systemic change that could improve the community writ large: support rather than solidarity.

However, the goal of onsite childcare, briefly realized more than a decade ago, has not been revived as a request. The Care Grants have become the long-term solution, although peer organizations, from the American Chemical Society to the American Academy of Religion/Society for Biblical Literature have onsite childcare, and, for its part, KiddieCorp has been offering their services for going on 38 years. Yet in 2024, what will conference participation even look like? What is the continuum of desires for support as the equity gap across institutions widens? What are the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, and reduced travel funding for professional engagement, movement of conference-going to virtual spaces, and how will this affect the participation of different member groups with these kinds of historically important professional opportunities? Within the broader considerations of the Feminist Caucus and other feminist groups within rhetoric and writing studies and their intersectional goals of inclusion, what should access look like going forward?

Conclusion

It’s worth considering the relative success of these three efforts at feminist activism and disciplinary coalition building in terms of intentions and actions, and ideological versus material commitments. The development of the CCCC Women’s Committee and its evolution to the Feminist Caucus demonstrates the success of Betty Renshaw and Nancy Prichard’s stealth efforts and the impact of Robert Hogan’s kairotic moment of meeting sleepiness. It took 15 years for the committee to be formally charged within CCCC, but its fiftieth birthday suggests that the committee has had staying power, and its archive demonstrates effective advocacy on behalf of its constituents (elsewhere we have also written about the missteps and complex history of the Caucus, see Graban, Hassel, and Pantelides). Further, the work of the Guidelines is memorialized in the discipline’s annual convention programs, and has been so successful that the addendum allowing the use of sexist language when indicated by an editorial footnote has not – to our knowledge – ever been utilized. The efforts of what became the Feminist Caucus insured implementation of the Guidelines with assertive, unwelcome insistence of its adoption.

Yet, the childcare initiatives, called for consistently beginning in 1971, stalled in each of their iterations. For a “feminized” (Schell, 1998), applied field such as ours to continually ask for on-site childcare and only have it offered for two of our fifty years suggests the vast difference between ideological and material feminist responses, between support and solidarity. No feminist change is easy, and both the creation of the Committee and the development and implementation of the Guidelines demonstrate how difficult it is to bring about linguistic change and inclusive practice. But on-site childcare required the operationalization of the beliefs undergirding feminist changes in the discipline. They also required budgeting. Thus, it is particularly metaphorically appropriate that on the cusp of institutionalizing childcare at the conference, funds were diverted for scholarship.

Our discipline has long been torn on how to include the “teaching majority”: instructors in our field who are not represented in our scholarship, who are teaching the majority of our courses, who we say we value but whose influence is devalued (see Larson, 2018; Hassel, 2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, teacher-scholars made this visible through a variety of multimodal projects and traditional and nontraditional academic texts (see, Prielipp; Lumumba; Michaud, and other essays in the Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics’ special issue on Carework and Writing during Covid, and Lindquist, Strayer, and Halbritter’s 2022 anthology of ‘documentarian tales,’ collected stories of teacher-scholarship-care work during the early months of the pandemic).

Making visible the strategies that feminist teachers and scholars have used to bring about change is one start, and creating scholarly spaces like the JOMR special issue and documentarian tales are how we might make more visible our feminist humble histories and the daily work of members of our field whose labor is marginalized and devalued. As long as the material needs of the teaching majority are viewed as peripheral to their participation in the professional conversations of the field, however, we will have an incomplete picture of who we are. As the CFP for this cluster conversation notes in quoting Audre Lorde, “We are anchored in our own place and time, looking out and beyond to the future we are creating, and we are part of communities that interact. While we fortify ourselves with visions of the future, we must arm ourselves with accurate perceptions of the barriers between us and that future” (57). We take heart in chronicling the feminist coalition building of the Feminist Caucus and its early iterations, yet our primary barrier remains: operationalizing our values, prioritizing access for all members of our coalitions, demonstrating not just support, but solidarity.

Works Cited

Gabor, Catherine, Stacia Dunn Neeley, and Carrie Shively Leverenz. “Mentor, May I Mother?” In Stories of Mentoring: Theory and Practice, edited by Michelle F. Eble and Lynee Lewis Gaillet, 2008, pp. 98–112. Parlor Press.

Ghodsee, Kristen, and Rachel Connelly. 2014. Professor Mommy: Finding Work-Family Balance in Academia. Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

Hassel, Holly. 2022. “2022 CCCC Chair’s Address: Writing (Studies) and Reality: Taking Stock of Labor, Equity, and Access in the Field.” College Composition and Communication, 74 (2): 208-228. https://library.ncte.org/journals/CCC/issues/v74-2/32273

Larson, Holly. 2018. “ Epistemic Authority in Composition Studies: Tenuous Relationship between Two-Year English Faculty and Knowledge Production.” Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 46, no. 2, 2018, pp. 109-136. https://library.ncte.org/journals/TETYC/issues/v46-2/29948

Mason, Mary Ann, Nicolas H. Wolfinger, and Marc Goulden. Do Babies Matter? Gender and Family in the Ivory Tower. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2013.

Mueller, Derek, Kate Pantelides, Laura Davies, Matt Dowell, Alanna Frost, Mike Garcia, Rik Hunter. “Polymorphic Frames of Pre-tenure WPAs: Seven Accounts of Hybridity and Pronoia.” Kairos, vol. 21, no. 1, 2016. https://kairos.technorhetoric.net/21.1/topoi/mueller-et-al/index.html

National Council of Teachers of English. Committee on the Status of Women Archival Files from the University of Illinois-Champaign library. https://www.dropbox.com/home/CCCC%20Status%20of%20Women

Lindquist Julie, Bree Strayer, and Bump Halbritter. Recollections from an Uncommon Time: 4C20 Documentarian Tales. The WAC Clearinghouse, 2023. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/swr/documentarian/

Lumumba, Ebony. “Starved for Color: Work, Mothering, and Covid,” Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, vol. 7, no. 1, 2022. http://journalofmultimodalrhetorics.com/7-1-lumumba

Michaud, Christina. “Read, Write, Cook, Repeat: The Intertwining of Pandemic Parenting and Scholarship.” The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, vol. 6, no. 2, 2022. http://journalofmultimodalrhetorics.com/6-2-michaud

Osorio, Ruth, Vyshali Manivannan, and Jessie Male, eds. Special issue on Carework and Writing during COVID, Part 1 and 2. The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, vol. 6, no. 1 and vol. 7, no. 1. http://journalofmultimodalrhetorics.com/6-2-issue-toc

Prielipp, Sarah. “It’s So Hard: Caregiving during Covid.” Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, vol. 6, no. 2, 2022. http://journalofmultimodalrhetorics.com/6-2-prielipp.

Seigel, Marika. Rhetoric of Pregnancy. University of Chicago Press, 2013. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226072074.001.0001.

Slaughter, Ann-Marie. “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All.” Atlantic, July/August 2012. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/07/why-women-still-cant-have -it-all/309020/.

Sallee, Margaret W. “Gender Norms and Institutional Culture: The Family-Friendly versus the Father-Friendly University.” Journal of Higher Education, vol. 84, no. 3, 2013, pp. 363–96.

https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2013.0017.

Schell, Eileen. Gypsy Academics and Mother-teachers: Gender, Contingent Labor, and Writing Instruction. Boynton, 1998.

Endnotes

[1] We affectionately refer throughout the piece at times to “Betty and Nancy” because of how often they are referred to in the archival documents together.

[2] At the time of these events, the CCC editor was a member of the CCCC Officers’ Committee. That structure has changed such that the representative editors of CCCC-associated publications serve ex officio, non-voting roles on the Executive Committee.

[3] The history of the group’s structure and evolving naming is as follows: The NCTE Committee on the Role and Status of Women in the Profession, the NCTE Women’s Committee, the CCCC Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession, the Standing Group on the Status of Women in the Profession, and the Feminist Caucus.

[4] We can’t help but remark upon the strange unstated assumption that the skill sets of graduate students or unemployed linguists would overlap with the skill set of providing competent childcare.

PDF

PDF