For Lisa: A Patchwork Quilt

For Lisa: A Patchwork Quilt

Peitho Volume 24, Issue 1, Fall

Author(s): Michael J. Faris

Michael J. Faris is an Associate Professor of Technical Communication and Rhetoric in the English department at Texas Tech University. He was writing program administrator for the First-Year Writing program from 2018-2021 and researches and publishes on digital literacies and rhetoric, queer and feminist theory, and writing program administration.

Tags: feminist scholarship, in memoriam, memorialI was only ten years old when Lisa Ede and Andrea Lunsford published Singular Texts/Plural Authors. I am embarrassed to say, I didn’t read this book until after Lisa’s death. Less than a week after Lisa’s passing, I sat in my colleague Becky Rickly’s office as she pointed at her bookshelf and talked about how she’d have to give away all these books when she retires. I noticed Lisa and Andrea’s book on her shelf and grabbed it, selfishly. Longingly. Becky explained how she borrowed the book from Mick Doherty and wasn’t able to return it before he passed away in 2013. So there it sat. I asked if I could have it, and Becky said yes. How much of our reading and writing is haunted by death and the loss of loved ones? How much of our scholarly work is a collaboration over time, with the voices of our mentors shaping us, and the texts and memories they have given us carried with us?

* * *

I first met Lisa in September 2005 when I started my master’s degree at Oregon State and took her class on language, technology, and culture. I had no idea Lisa was such a big deal when I applied to OSU, nor really when I met her. If you met Lisa, you would have no idea she was a big deal. She was so humble, so unassuming.

Lisa’s class, along with teaching first-year writing at OSU and taking Vicki Tolar Burton’s class on teaching writing, convinced me to switch my MA emphasis from literature to rhetoric and writing. Like Lisa, I had wanted to be a teacher for a long time. And, like Lisa, academia had drawn me momentarily away from teaching towards wanting to study literature, but teaching drew me back to pedagogical commitments. As Lisa writes, “my teaching drew me back to my aspirations as a teacher. With my ‘conversion’ to rhet/comp, I felt a renewed sense of pedagogical commitment and purpose” (“How to Get” 21-22).

* * *

One of my favorite stories Lisa would tell (and re-tell) was of her time at Wisconsin–Madison during the Vietnam War. I don’t remember all the specifics, but she explained that after a protest was broken up, she hid from the police on some family’s porch or behind their bushes. When the family saw her, she was certain she’d be kicked off the property and arrested or assaulted by the police, but instead, the family allowed her to stay. I know this was the 1970s, and Lisa was young. But when she told this story, I didn’t imagine a young woman. I imagined Lisa from the late 2000s hiding on this porch behind bushes, a 60-year-old woman with gray hair, immensely curious, kind, and stubborn all at once.

* * *

One of the most rewarding activities we did in Lisa’s graduate courses was to read each other’s I-Search Essays (a brief essay exploring our personal investments in a research project) and then to write short 3-5-sentence “Valentines” to each other about what we enjoyed about the essays (criticism was forbidden). We’d spend part of a class period handing out our Valentines, then reading them privately, and then talking about the experience of reading each other’s projects, writing the Valentines, and receiving and reading our Valentines. This was such a wonderful community-building activity—and an affirmation of each of us as individual writers—that I’ve used it in my first-year writing classes multiple times. Lisa helped me to not only see the value of community-building in my teaching but also how to be intentional in building communities of writers in my classes. (See Lisa’s Situating Composition 209-215 for a discussion of the I-Search Essay, this activity, and how she approached teaching graduate-level composition courses.)

* * *

Lisa was immensely curious and promoted that curiosity in her students. I wrote a final project for her composition theory class that was hypertextual with multiple nodes and links. It was hard to read and navigate, with very little coherence as a seminar project. I no longer have Lisa’s comments on the project (it was a WordPress install on my OSU page that has since been lost), but I do remember her commenting that she felt like she didn’t know how to read it. I think Lisa wasn’t sure how to read many of my projects in that class. But she also encouraged me to continue the lines of inquiry around composition, composure, and new media theory.

My I-Search Essay for Lisa’s composition theory class was inspired by Geoffrey Sirc’s “Never Mind the Tagmemics,” a queer and anti-racist desire for social justice and change, and punk aesthetics and music. Rather than a traditional essay, I created a collage, cut-and-pasted together with scissors and tape like a zine. I included quotations from Sirc and punk lyrics, and I photocopied and taped on handwritten comments from my classmate Marieke, who had provided me feedback on a previous draft.

I had no idea at the time that Lisa had already written these words: “Experiment with ways of expanding scholarly genres and of resisting the conventional ways that knowledge circulates in composition—but recognize the potential difficulty and complexity of such efforts” (Situating 200).

* * *

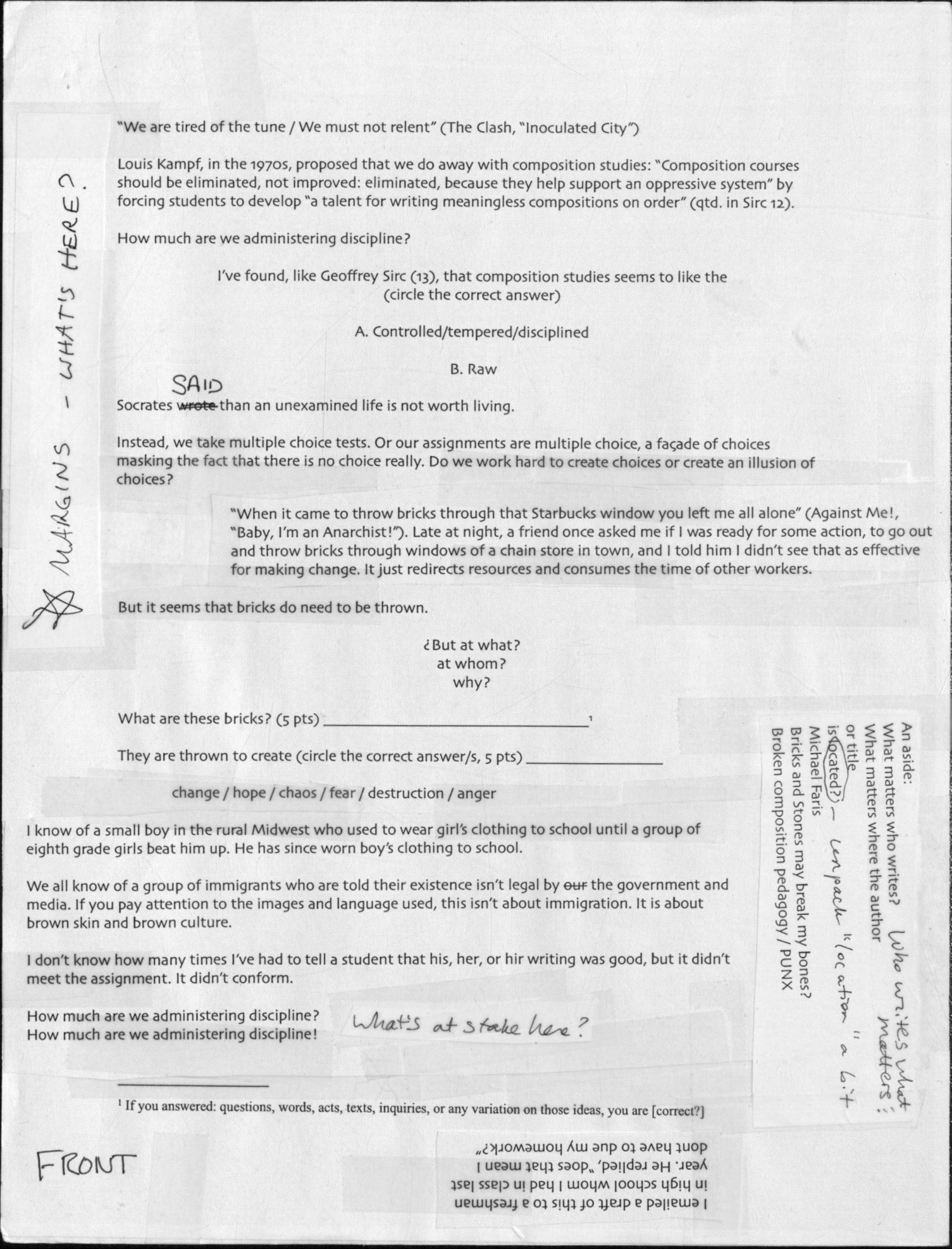

Figure 1. The frontside of my 2006 I-Search Essay for Lisa’s class. Image description: a page of typed words, formatted creatively: some lines are upside down, some are in the margin, some are centered, and some are left-aligned. The words mix memoir and analysis, and some of the writing is in the form of test questions, parodizing testing. On the page are Lisa Ede’s short handwritten comments.

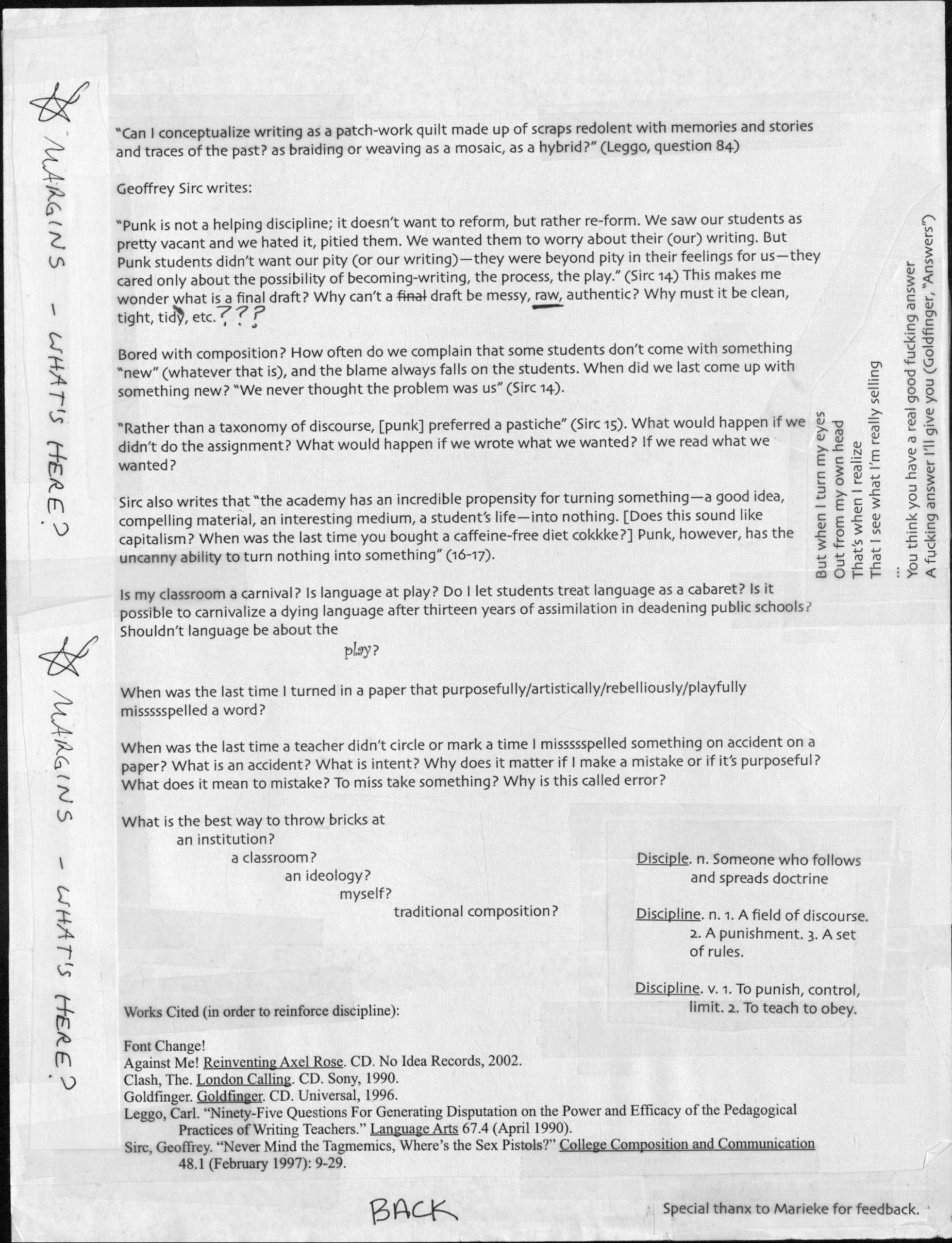

Figure 2. The backside of my 2006 I-Search Essay for Lisa’s class. Image description: another page in the same assignment, with quotations from Geoffrey Sirc and short responses. Like the previous page, blocks of text are formatted freely, with some text centered and some running vertically up the right side of the page. Lisa’s short comments are encouraging Michael to use the margin space, literally and figuratively.

* * *

Lisa encouraged me and provided space for me to see the connections between my developing queer and antiracist politics, new media, and rhetoric and composition. Late in life, Lisa wrote about how she didn’t at first see connections between her scholarly work and her personal feminist commitments (“How to Get” 25). She clearly learned from that experience and encouraged that connection-making in her students, particularly how intertwined the personal and the academic are. Now, 15 years later, as a teacher and an administrator, I see how Lisa’s stress on the intertwinement of the personal and scholarly has shaped my commitments and practices. Before I ask why others should care about a project, I ask why my students care. What are our “passionate attachments” (Situating 195, quoting Jacqueline Jones Royster) to this project? What drives you in this project?

* * *

This memorial is a collage—a “patch-work quilt,” to quote Carl Leggo’s “Ninety-five Questions” (405), one of the first essays Lisa encouraged me to read—because I don’t have faith in linearity. Lisa didn’t know how to read my intertext hypermedia project in her composition theory class. I don’t know how to read my grief.

* * *

When I teach TTU’s graduate course on Histories and Theories of Composition, I assign the opening pages of Lisa’s Situating Composition. “What are we talking about when we talk about composition?” Lisa asks (3). The opening questions of Situating Composition (3-4) are the opening questions of our field. I don’t know if there are two pages in the field that so succinctly state (or, more accurately, ask) what is at stake in what we do and study.

Lisa gave me a copy of Situating Composition when I defended my MA thesis. As I write this, I return to Situating Composition, especially the strategies Lisa provides “to encourage readers to consider the advantages and disadvantage of particular practices for their own scholarly inquiry” (192). As I reread, I am astonished again by the integrity and ethics informing these practices, asking scholars to theorize practices but also to see theory as a situated set of practices that requires reflexivity, historicity, and generosity, as well as critique, experimentation, and situating of both oneself and of one’s practices.

* * *

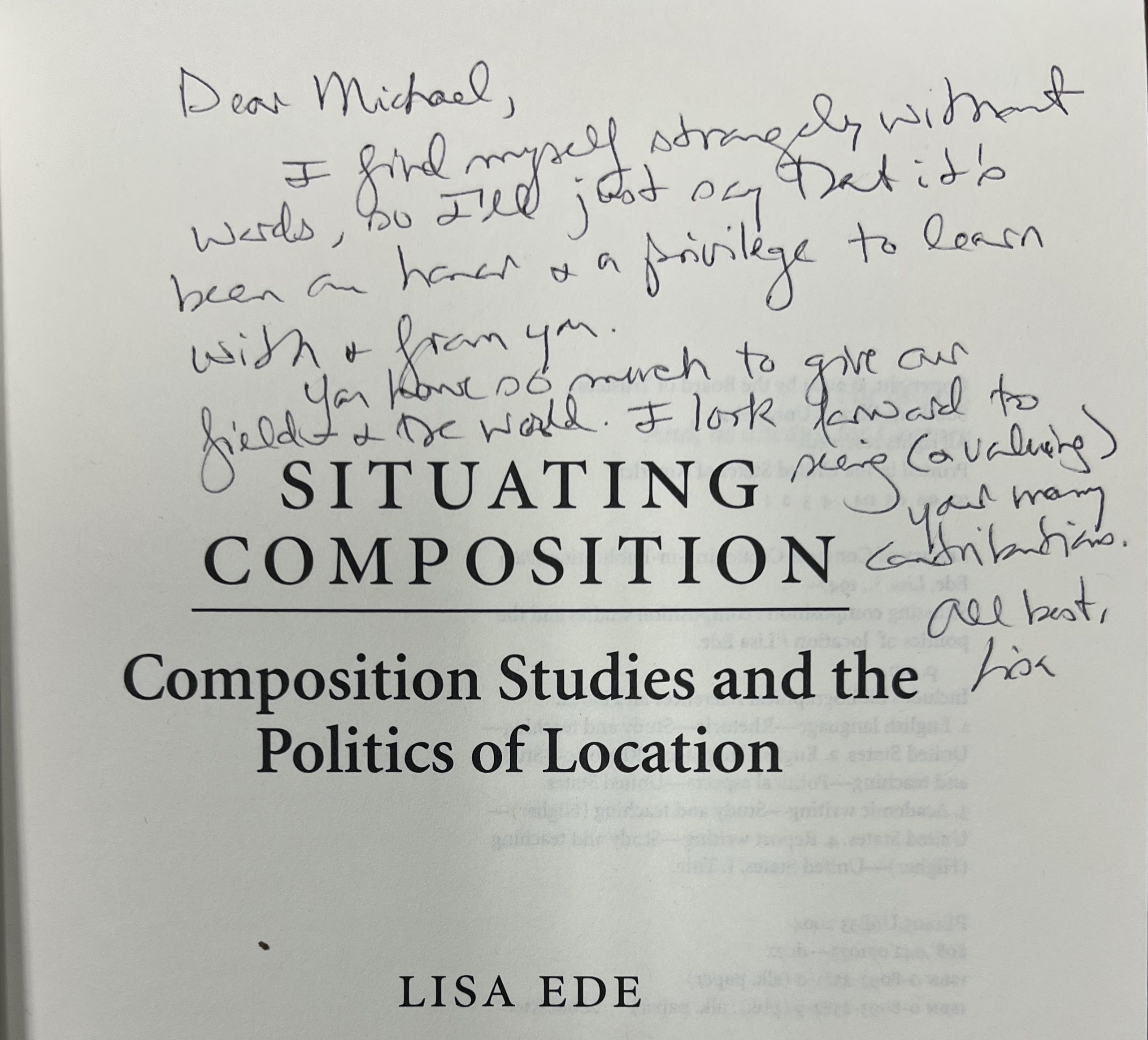

Figure 3. Lisa’s 2007 inscription in my copy of Situating Composition. I share this because I find Lisa’s handwriting so beautiful. In 1990, my third-grade teacher told my class that someone in the Talented and Gifted program had such messy handwriting that they didn’t belong in the program. I don’t know for sure, but I think she was talking about me. When I look at Lisa’s handwriting, I’m reminded of Lisa’s immense love but also how her scholarship and teaching challenged the norms of literacy, like the one my third-grade teacher reinforced. Lisa’s handwriting is difficult for me to decipher but also incredibly beautiful. I feel all sorts of pleasure in how my third-grade teacher would read Lisa’s writing as “messy.” Image description: the title page of Situating Composition with Lisa’s note: “Dear Michael, I find myself strangely without words, so I’ll just say that it’s been an honor and a privilege to learn with & from you. You have so much to give our field & the world. I look forward to seeing (& valuing) your many contributions. All best, Lisa.”

* * *

Lisa wrote to me that it was “an honor and privilege to learn with and from you.” I think I learned from Lisa that teaching is a matter of learning with and from our students. Lisa taught me that while we do have a lot to offer our students, they have more to offer us as we learn together.

* * *

My first conference presentation was a collaboration with Lisa for The New Research Summit at the University of Oregon in 2006, where Lisa discussed Amazon citizen reviews and I discussed student blogging. Most of my publications since have been collaborative—with my mentors at Penn State or with colleagues or graduate students at Texas Tech. Lisa explained to me personally—and to all of us in writing (“How to Get” 23-24)—that collaboration was met with resistance or suspicion from tenure and promotion committees. I believe it was because of Lisa’s (and so many others’) precedents in the field that led to little resistance to the frequent collaboration in my dossier for my tenure case. Lisa changed our field, not simply in ideas in print, but in practices and in values.

* * *

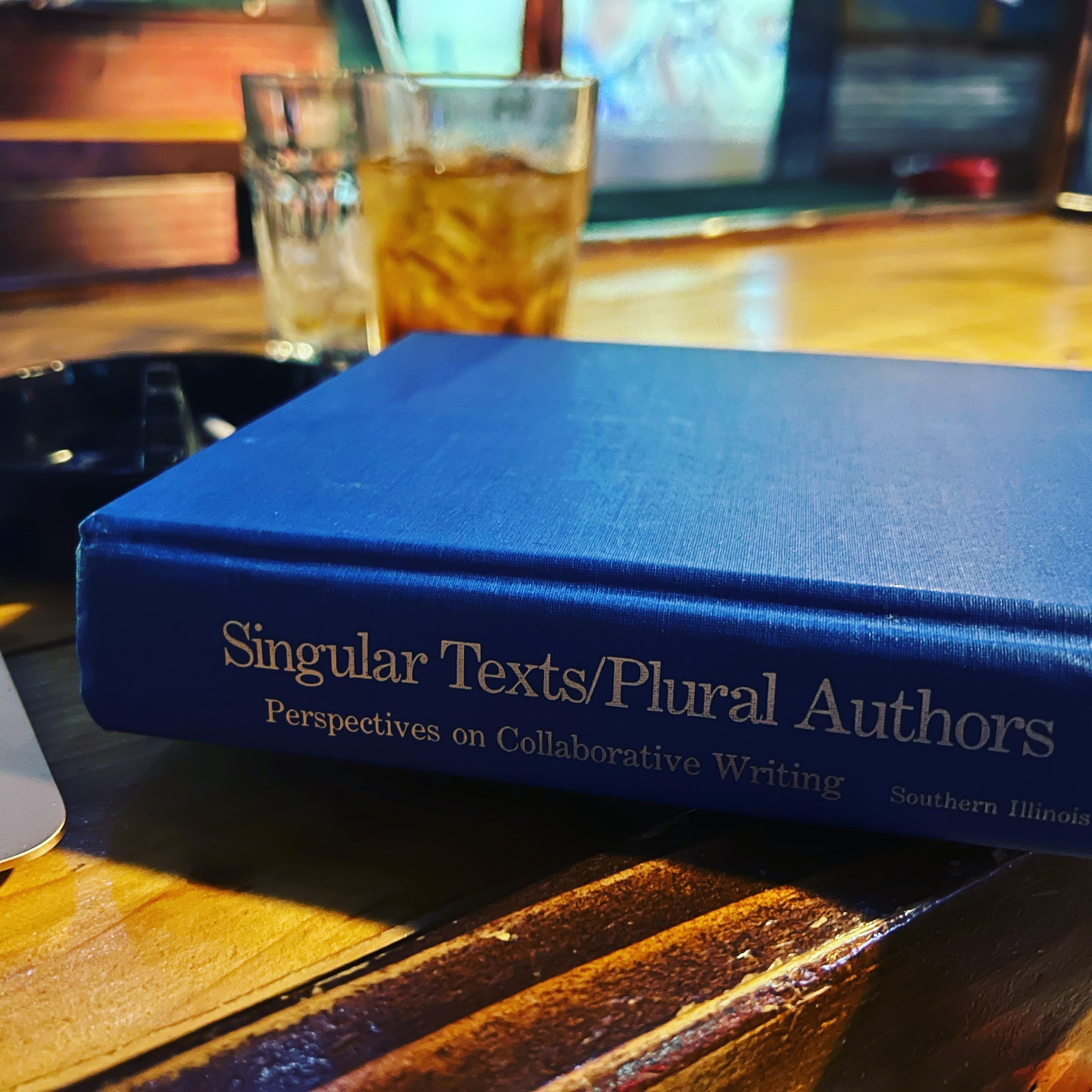

Lisa helped me attend to the situations of composing. I write in coffee shops and bars, with a body—elated, frustrated, crying. I pay attention to the materiality of my writing because of Lisa. I write this at my favorite bar, with Lisa and Andrea’s book near me, a whiskey and coke, a pack of cigarettes, my eyes flooded with tears.

Figure 4. Workspace at the bar: Reading Lisa and Andrea’s book and writing this essay with a whiskey and coke. Image description: a close-up of the spine of the book Singular Texts/Plural Authors, its solid blue cover without a dust jacket. The book is placed on a polished wood bar. Just behind the book, out of focus, is a black ashtray and two drinks: one whiskey and coke and the other empty, finished, except ice.

* * *

I worry my words in this memorial aren’t right. They aren’t enough. When Clancy Ratliff emailed me about contributing to this memorial, she wrote, “whatever you give us will be the right thing.” I don’t know if this is the right thing.

In her essay republished in this issue, Lisa asks, “how do I avoid the potential narcissism inherent in a focus on my research, my career? What do I have to say, I found myself asking over and over as I sat fretting at my computer, that might be of some use to those who are earlier in their scholarly and professional paths?” (“How to Get” 27-28). I ask myself similar questions as I fret at my computer. How do I avoid the potential narcissism inherent in a focus on my relationship with Lisa? What do I have to say that can matter to others? One of my many takeaways from my relationship with Lisa and her scholarship (including her essay reprinted in this issue) is that relationships (mentoring, friendships, etc.) are part of what we learn to do when we learn to be part of a discipline or profession. They need to be intentionally fostered and cultivated with care and curiosity. Lisa epitomized that intentional care and curiosity, and she taught so many of us how to practice our commitments to our students and to each other.

Works Cited

Ede, Lisa. “How to Get a Nonacademic Position.” Women’s Professional Lives in Rhetoric and Composition: Choice, Chance, and Serendipity, edited by Elizabeth A. Flynn and Tiffany Bourelle, The Ohio State UP, 2018, pp. 18-29.

—. Situating Composition: Composition Studies and the Politics of Location. Southern Illinois UP, 2004.

Ede, Lisa, and Andrea Lunsford. Singular Texts/Plural Authors: Perspectives on Collaborative Writing. Southern Illinois UP, 1990.

Leggo, Carl. “Ninety-five Questions for Generating Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of the Pedagogical Practices of Writing Teachers.” Language Arts, vol. 67, no. 4, 1999, pp. 399-405.

Sirc, Geoffrey. “Never Mind the Tagmemics, Where’s the Sex Pistols?” College Composition and Communication, vol. 48, no. 1, 1997, pp. 9-29.