Feminists (in) Dialogue: Mapping Convergent Moments and Telling Divergent Histories of the CCCC Feminist Caucus and the CFSHRC

Feminists (in) Dialogue: Mapping Convergent Moments and Telling Divergent Histories of the CCCC Feminist Caucus and the CFSHRC

Peitho Volume 24 Issue 4, Summer 2022

Author(s): Tarez Samra Graban, Holly Hassel, and Kate Lisbeth Pantelides

Tarez Samra Graban is an associate professor and honors teaching scholar at Florida State University. She is a former president of the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, and a current assistant co-chair of the Global & Non-Western Rhetorics Standing Group of the CCCC. She is the author of Women’s Irony: Rewriting Feminist Rhetorical Histories; co-author of GenAdmin: Theorizing WPA Identities in the 21st Century (with Charlton, Charlton, Ryan, and Stolley); and co-editor of Teaching through the Archives: Text, Collaboration, Activism (with Hayden) and Global Rhetorical Traditions (with Wu). Her scholarship has appeared in a range of peer-reviewed journals and edited collections.

Holly Hassel is Professor of English and Director of First-Year Writing at North Dakota State University. Before that, she was a faculty member at the University of Wisconsin-Marathon County, a two-year open-access campus. She is past editor of Teaching English in the Two-Year College and in 2022, chair of the Conference on College Composition and Communication. Her most recent work is Materiality and writing Studies: Aligning Labor, Scholarship, and Teaching (Studies in Writing and Rhetoric series, 2022) with Dr. Cassandra Phillips. Her scholarship has appeared in a range of peer-reviewed journals and edited collections.

Kate Lisbeth Pantelides is an associate professor and Director of General Education English at Middle Tennessee State University. She teaches rhetoric, composition, and technical communication courses at the undergraduate and graduate levels. Her research interests addresses rhetorical genre studies, discourse analysis, feminist rhetoric, and writing program administration. Her most recent works include Try This: Research Methods for Writers, with Dr. Jennifer Clary-Lemon and Derek Mueller, and A Theory of Public Higher Education, coauthored with the TPHE Collective.

Abstract: In recognition of Peitho’s tenth anniversary, this collaborative retrospective essay maps the parallel, intersecting, and diverging trajectories of the Feminist Caucus and the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, including the spaces we have yet to reach. Decades after their respective beginnings, the divergent and overlapping missions of these groups offer rich insight into what it means to contribute to intersectional work toward (or in) feminist/equitable labor, as well as the challenges of recouping organizational histories through living archives

Tags: archives, CCCC, cfshrc, Feminist Caucus, labor equity, organizational history, politics of the professionTO ACKNOWLEDGE the impact of all the feminist energy and commitment expressed in the high level (sound and content) of our table talk in KC

TO CHANNEL some of the humanistic power swirling over the lukewarm soup, limp lettuce, and greasy chicken.

To ASSERT a founding momma’s right to defer to the energy and vision of the Young.

—from a 1978 newsletter circulated by leaders of “The Women’s Committee” of 4Cs

Though the discipline of rhetoric and writing studies (RWS) has a clear trajectory of feminist scholarship stretching back decades, the impact of disciplinary work that has taken place in spaces outside of scholarship and publication is less visible (and often, less valued: see Almjeld and Zimmerman, “Invaluable”; Cole and Hassel, Surviving; Detweiler, LaWare, and Wojohn, “Academic Leadership”; Hassel and Cole, Academic Labor; Gindelsparger, “Trust on Display”). This article traces the evolution of two feminist groups in the field: the Conference on College Composition and Communication’s Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession, more recently known as the Feminist Caucus (the CSWP/FC),[1] and the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition (the Coalition)[2]. This retrospective piece maps the parallel, intersecting, and sometimes divergent stories of feminist collaborations in RWS, including the spaces we have yet to reach. It also reflects the somewhat porous boundaries of RWS as both the Caucus and the Coalition have historically attracted members from outside of Rhetoric and Composition.

In particular, we trace the trajectories of both organizations using different views of feminist work based on our examination of available archival materials, and we offer a selective visual timeline of the two groups’ activities and an analysis and overview of their structure, development, and values. As the CSWP/FC and the Coalition have matured and stabilized as organizations, some priorities have intensified and others have fallen away. This article attempts to better understand their relationship to each other and how their priorities and efforts have evolved over time, capturing their diverging perceptions as much as is reasonable here.[3] Our hope is that by placing these stories in conversation, we can show how each group negotiates certain ideological, practical or institutional tensions, and, thus, where new tensions and interventions related to feminist work can be more productively shared and lived out.

In attempting this work, we acknowledge the impossibility of “telling the story correctly,” as well as the danger of a “single story” (Adichie). We emphasize the necessarily selective and uneven nature of this work and of our timelines, and we acknowledge that historians interested in studying our organizations’ histories must always contend with a potentially lopsided view of things, i.e., where more attention is drawn to recent initiatives and debates over those that occurred in decades past. As such, we offer a preliminary reflective commentary on the challenges of building and using feminist archives. It is safe to say that both organizations have yet to recover their earliest periods of activity through archival documentation, some of which has been subsumed into individual members’ private collections, or exists better in the form of yet untapped oral histories. Moreover, all participants in both our organizations perceive their own sense of each group’s histories. By documenting this feminist work, we hope only to strengthen our disciplinary understanding of the relationships between the two groups and the potential for coalitional feminist advocacy, as well as the importance of staying close to our histories even as we reach beyond them.

That said, we approach this project with critical minds and full hearts, a bodymind orientation (Price) that takes into account our relationship to these organizations, ones that we think are important to the discipline and to which we have literally contributed our blood, sweat, and tears. We are by no means distant observers (of course, no one is), and as former chairs of these groups, we are invested in their successes and feel at times complicit in their missteps and oversights, even as we have supported their evolution. We are acutely aware of how no organization is able to shed its beginnings and instead carries its initial structures, missions, and composition through its lifetime. We are also acutely aware that others have had the same ideas before us. All of us, whether we have served our organizations as leaders or as members, strive to hold our own ideas lightly and with humility—to be aware of how those ideas have been responded to in the past, what has been proposed and rejected, what has been successful but forgotten, whose efforts have been celebrated and then erased. Ultimately, we are reminded that longer-term thinking is still and always essential for feminist work in our field.

Our project, then, attempts to capture the impact of these beginnings and follow these traces to the present day. Our roles in the organizations and our subject positions as tenured women faculty provide us privileged windows inside the inner workings, but they also make invisible some of the inherent tensions, and we welcome further attention to and research that draws on the archives from which we offer the following analyses and observations. Even amongst these three co-authors we struggle to offer a single coherent story, to offer an ethical interpretation of living documents, and we invite feminists in the discipline to further weave these beginning threads into fuller (even contestable) narratives. In discussing the task of rhetorical historiography, Cheryl Glenn notes that “historiographies must do more than simply rescue, recover, and reinscribe neglected rhetors” (105). We take this to heart in constructing a brief, incomplete, rhetorical near-history of feminist work in RWS.

(Re)Constructing an Archive

Welcome to the first issue of _____ There is a blank at the beginning of our project, just as the histories we’re in the process of creating often begin with blanks where the women should be. We begin this newsletter with two kinds of names: one very long and cumbersome and the other, not yet created (see the contest information on page 2), an antithesis that captures the challenge of creating new histories.

—“Letter from the Editors,” Peitho: Newsletter of the Coalition of Women Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, vol. 1, no. 1, Fall 1996

For this work we draw on extensive but incomplete archives. The documents that comprise each group’s history exist in multiple sites and formats, such that neither of the two groups has a single, comprehensive archive from which to draw conclusions. While we have access to some founding documents, part of the difficulty of archival work, and the early 1970s work of the CSWP/FC in particular, is that our records are woefully incomplete, and we must draw on critical imagination (Royster and Kirsch) to recognize the collective of women who contributed to its beginnings. The CFSHRC, in particular, is richer in its memories of the conversations that led to its founding than in actual founding documents. The more recent artifacts in the archival records of these two organizations prompt us to question what we understand about the groups and our relationships to them. Thus, we’re struck by Jenny Rice’s question in Awful Archives, “How does evidence happen?” and her recent examination of the nature of evidence in archival work.

For our purposes, we’re interested in how the patchwork evidence we have examined tells different, sometimes conflicting stories of feminist work in RWS that periodically differs from our own memories and experiences. Thus, we triangulate these discursive artifacts with our own, disparate memories of key events, and even our calendars, emails, and notes from conferences and related activities. In her work accounting for the complexities of archival research and constructing attendant histories, Jennifer Clary-Lemon reminds us how

[we] do not ever have a discrete set of “facts” in the recovery and positioning of archival history […] rather than push away the messiness of archival research processes that come up against various limits, absences, and distances, we need to recognize that that meaning we draw from such concepts cannot be separated from the matter and material of archives. (“Archival” 398)

In this project we embrace the “limits, absences, and distances” as a necessary part of our process, one that co-authorship usefully complicates and problematizes.

Figure 1: Masthead from a 1978 newsletter of the 4C’s Feminist Exchange. Image Description: Screen shot of the header on a 1978 newsletter for the 4C’s Feminist Exchange. The title is handwritten, but the typed text reads: “a newsletter conceived in the joy and enthusiasm of all 139 of us sharing, listening, thinking, responding, laughing, planning.”

CSWP/FC

Since the CSWP/FC was originally conceived as a CCCC Committee (in 1983), the Feminist Caucus has written yearly reports. These reports as well as membership lists have been archived by NCTE and made available to us in advance of this work. In 2019, the Feminist Caucus began the work of organizing archival documents of the Feminist Workshop, a pre-convention gathering held annually at the Conference on College Composition and Communication’s national gathering, and launched the Feminist Workshop archive on their website. Formal reports to the organization and the CCCC Executive Committee were provided to us by the CCCC Staff liaison, starting with the earliest available in 1987, and there is a somewhat robust set of documents that can help trace the activities of the group between 1987 and the present.

To learn more about the feminist work taking place in formally charged groups prior to 1987, we requested and received copies of correspondence (letters and memos), data, and membership lists dating back to 1970 that had been archived by the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign in the NCTE archives housed there. These materials suggest that what became the Feminist Caucus started as what operated for a length of time as the “NCTE Women’s Committee,” initially charged by NCTE in 1970 as the NCTE Committee on the Role and Image of Women in the Profession and Council and simultaneously meeting informally at CCCC in the early 1970s. The group was often led by and included members working in higher education and who were college faculty, though NCTE is broadly inclusive of K-12 needs and interests.[4]

Later efforts of the group included the Women’s Exchange (sharing of documents, books, and other resources at the annual NCTE and CCCC conventions), women’s gatherings at the events (lunches or breakfasts). Significant labor was directed toward work that really did directly target the “role and status” of women: these included implementing the nonsexist language guidelines by reviewing issues of the major NCTE journals at the time (Language Arts, College Composition and Communication, College English, and English Journal) and provided a detailed set of feedback on the year’s issues in terms of comportment with the guidelines. They also advocated heavily to ensure that the annual conventions were not held in states that had not yet ratified the Equal Rights Amendment (including a proposed boycott of the Kansas City convention to be held in Kansas City, KS in 1977); developing and issuing awards for books that used nonsexist language to be presented at the annual convention; preparing and publishing a book, Classroom Practices in Teaching English: Responses to Sexism, with members of the group sharing guest editor credit for the work with the series editor, Ouida Clapp.

Some documents suggest that a survey was circulated on the status of women in 1985 that aimed to gather information about the demographics and experience of women in the profession; however we have not yet located any documents that report on the results of the survey. The work of the CSWP/FC includes documents from relatively diffuse activities, inclusive of the CCCC Women’s Network SIG, the Feminist Workshop, and the Annual Business Meeting. Coupled with the ongoing work of the Feminist Caucus, the materials we have only tell us so much about the organization, and there are stories we hope to tell in the future as we continue to unearth materials, learn from past members, and make sense of this rich history. In this article, we focus primarily on the governance and service work of the group that began as the NCTE committee on the Role and Image of Women in the Profession, and as the timeline shows, over time became its own CCCC committee and is now at present a Standing Group of the organization, the CCCC Feminist Caucus.

Figure 2: Header from the Coalition’s website, reflecting the 2016 name change. Image description: Screen shot of the current website header for the CFSHRC, with the name in block letters, and each letter containing the line drawing of a feminist historical figure. The accompanying tag line reads “Rhetorics from the 5th century BCE; Coalition since 1989.”

The Coalition

The Coalition was originally conceived in 1988–1989[5] as an auxiliary group to the Rhetoric Society of America and CCCC, but operating independently of both groups, that would host semi-annual business meetings, sponsor an evening meeting at the annual CCCC, and meet formally and informally throughout the year, usually depending upon who was available to meet among the founding members and Advisory Board. Even before co-sponsoring the first Feminisms and Rhetorics conference in 1997, most of the Coalition’s business and outreach occurred at or around field conferences and, eventually, via e-mail or online. Lacking a single institutional or organizational home, and thus lacking a physical repository for its documents, archiving the CFSHRC’s histories has presented an ongoing challenge. In addition, defining what can and should constitute the organization’s “archives” is a subject of ongoing conversation, as there has always been a full slate of official business conducted by the Advisory and Executive boards, but just as important to the Coalition’s identity are the activities of its members, and its discursive activity across three social media channels (“Count ‘em”).[6] For these reasons and more, just like the CSWP/FC, the Coalition’s histories are multiple and its archives are still emerging.

Between 2011 and 2013, the Coalition began building a web-based archive of key administrative documents for its officers and members. In 2013, that digital archive project expanded in scope, with the goal of capturing and organizing its past and present histories in a way that made sense for an organization conducting most of its business through e-mail or electronic exchange, while also making visible information that would most interest feminist researchers. Constructing it in this way has helped spawn several creative historical projects, including a series of videos and films, and an overview of the Coalition’s rhetorical activism within its own conference spaces. However, much of the organization’s early activities—if they were captured in paper or digital documentation—were unable to be recovered or are best observed through oral histories of founding members and past presidents (“Past Presidents”), through video and film, through the evolution of the Peitho journal, and through conference programs.[7] Unbound by a single historical narrative, the Coalition’s archive showcases several attempts at telling its histories during key moments in the organization’s growth, often to honor the retirement or memorialize the career of a past president or founding member.

Because the archive’s overarching structure was chosen to accommodate its first digital platform, we find that, at a glance, it does not reveal the range of activities undertaken by Coalition members over the years. However, a comprehensive finding aid was created in 2020, intended to illuminate both members’ and officers’ activities, and intended to be updated each year. At present, materials are available in a range of categories, including annual meetings, governance documents, treasurers’ reports, membership lists, photographs, videos, and artifacts from committee and task forces. In addition, there are annual volunteer surveys and there is evidence of a long-standing tradition that outgoing presidents compose reflections on their terms of service. These reflections were first published in the Peitho newsletter, then published in annual meeting reports and, since 2014, have been composed as posts on the Coalition’s public blog. Ultimately, some years and conversations are meticulously represented through these genres, as well as more recent blog posts, podcasts, and e-mail activity, while many others are not. Some administrative information is only accessible to the Executive Board each term, but most of the currently digitized holdings are publicly accessible to Coalition members and other researchers on request.

Preparing this article allowed us to reflect on the challenges of not just searching archives, but also building them. Archiving living organizations is a difficult task; archiving organizations whose members, missions, and documentation evolve only multiplies the difficulty.

Annotated Timeline

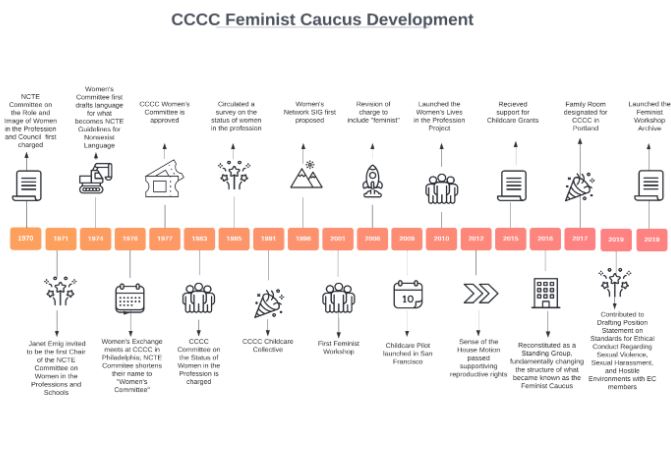

The CCCC Feminist Caucus was originally founded in 1983 and constituted as a CCCC special committee named the “Committee on the Status of Women.” However, it has a 13-year history prior to that first instantiation, emerging from work that took place beginning in 1970 as the NCTE Committee on the Role and Image of Women in the Profession. Figure 1 presents a visual timeline of the group’s structures, names, and major activities from 1970 to the present. Throughout its various iterations, the CSWP/FC has focused on the labor conditions for teaching faculty.

Figure 3: CCCC Feminist Caucus Development. This timeline highlights select accomplishments, structural changes, and evolution of the CSWP/FC from 1970 to 2019. Image Description: An infographic on a white background, conveying a visual timeline of CCCC Feminist Caucus Development through selected events from 1970 to 2019. The timeline constitutes the middle of the infographic as a series of dates in gradated colored squares progressing from light orange to pink, while each event on the timeline is explained above or below the date and is illustrated by an icon that visually depicts its sentiment, ranging from cranes to mountain ranges to stars to buildings to rocket ships.

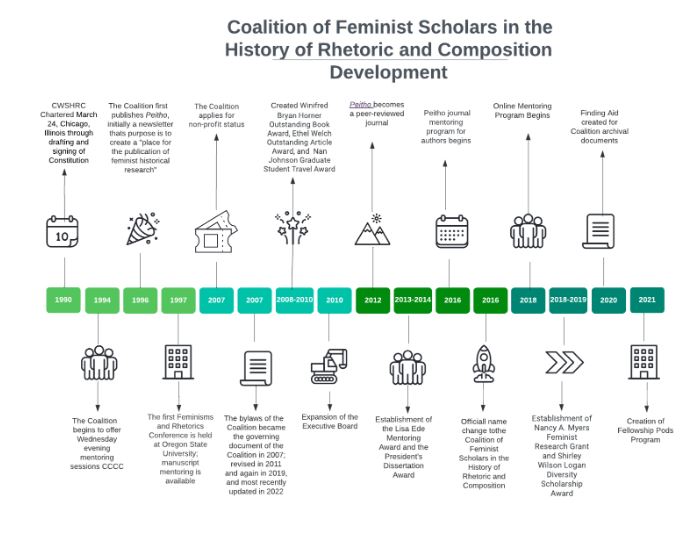

The Coalition of Women Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition was founded as a para-academic organization in 1989 and emerged with a two-pronged mission: to support feminist scholarly and historical projects, given that those projects were often marginalized in academic departments and throughout tenure and promotion processes; and to help women faculty and graduate students navigate the “politics of the profession,” including teaching and coping with work-life balance. They began hosting an annual pre-conference evening event at CCCC in 1990. At the 2016 annual business meeting, after a long discussion of survey and focus group results that were presented by a task force on mission articulation, the Advisory Board voted to officially change the organization’s name to Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition (“Annual”), reflecting both a shifting demographic and an expansion on topics, methods, and attitudes that might be called “historical” (Mastrangelo).

Figure 4: Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition Development. This timeline highlights select accomplishments, structural changes, and evolution of the organization from 1990 to 2021. Image Description: An infographic on a white background, conveying a visual timeline of CFSHRC Development through selected events from 1990 to 2021. The timeline constitutes the middle of the infographic as a series of dates in gradated colored squares progressing from light green to forest green, while each event on the timeline is explained above or below the date and is illustrated by an icon that visually depicts its sentiment, ranging from people groups to tickets to rocket ships to buildings.

Genre and Structure of the Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession (CWSP)

The CCCC Feminist Caucus has an august history within the organization, though some of its earliest work is not well-documented. What available documents confirm is that the group that eventually became the Feminist Caucus was originally called the “NCTE Women’s Committee.” Reports provided by the CCCC organization show that the 1983 committee first was assembled as a “Special Committee,” which is defined in CCCC constitution and bylaws as follows: “Special committees may be appointed by the Chair. b. Special committees will be appointed for a period not to exceed three years, but they may be renewed by action of the Executive Committee” (Constitution). The 1983 Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession, first chaired by Miriam Chaplin of Rutgers University,[8] was structured as and functioned within this kind of entity, requiring reconstitution every three years by the chair, officers, and/or Executive Committee, and with members appointed from the top down, by the organization’s elected leadership, typically the officers or the chair alone, as special committees have been convened. During a leadership period of 2014–2017, the CCCC officers sought to pare down the number of committees that had been functioning essentially as endlessly reconstituted special committees, and the leadership of the CSWP opted not to pursue reconstitution and instead apply to function as a Standing Group in 2016, also defined in the CCCC governing documents.[9]

With greater levels of grassroots agenda-setting possible and a greater level of self-determination, the SGSWP opted to be renamed as the Feminist Caucus in 2017, and the group has been operating according to open principles and within the functions provided for as organizational standing groups: standing groups are given particular privileges and have particular responsibilities, including a guaranteed sponsored panel/session at the annual convention, and a business meeting slot. However, with this level of autonomy and standing within the organization, the group has obligations (and constraints) within the larger organization, both CCCC and NCTE. For example, any standing group must provide a biannual report to the Executive Committee summarizing their activities, must receive CCCC approval before using the name on public documents; and official statements or documents must be reviewed by the CCCC officers prior to dissemination. Funding applications and surveys, as well, require review and approval by the sponsoring organization, CCCC and NCTE. This is to say that while the status within CCCC of a standing group provides access to some resources available through the organization (for example budget requests for group activities and local outreach grants to support group-sponsored activities at the annual convention) it is accompanied with responsibilities to the organization in the level of autonomy to make public statements when the CCCC name is used.

Genre and Structure of the Coalition

The Coalition has a multilayered structure, including a governance board since the first year of its existence, frequent volunteer groups and task forces, and an active membership on top of that. The group was formed from the outset as an independent entity, with the constitution serving as an article of incorporation and signed in 1990. The original statement of purpose indicated “The Coalition of Women Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition is a learned society composed of women scholars who are committed to research in the history of rhetoric and composition” (“Constitution”). The group evolved as a professional entity focused on scholarly and pedagogical support and mentoring (“Mentoring”; Fishman; Graban; Pettus), with a multi-pronged set of activities intersecting with and separate from CCCC (both the annual convention and the conference of NCTE), although one of its hallmark activities, mentoring tables, became a consistent presence at the annual CCCC in 1994.

The current mission prioritizes the “advancement of feminist research and pedagogy across histories, locales, identities, materialities, and media” and “the education and mentoring of feminist faculty and graduate students in scholarship, research methods, praxis, and the politics of the profession” (“About Us”). While work-life balance and institutional labor are not articulated as explicit goals, they are reflected in several documents across the archive as being inherent aspects of “politics of the profession,” and regularly appear as a mentoring offering at the annual pre-CCCC evening event.

In 2007, the Constitution was superseded by a more detailed set of bylaws that formalized the Coalition as a 501c3 corporation, which granted particular status in relation to its purpose, goals, and tax reporting, as well as outlined in significant detail the rights and responsibilities of the governing board and members. The bylaws emphasize activities related to professionalization and mentoring as the group’s primary focus, including “[f]ostering and encouraging scholarship, research, and interest in feminist histories, theories, and pedagogies of rhetoric and composition,” “[e]ncouraging exploration of the roles played by feminism and gender in the stories told about rhetoric and composition,” “sustaining a network of diverse scholars,” “providing education and mentorship in scholarship, research methods, and praxis,” “supporting, publicizing, and sponsoring events at conferences, institutes, and symposia,” and other activities related to research and scholarship such as publishing the Peitho journal and offering scholarships, travel grants, and awards.

Evolution of CSWP/FC: Purpose, Mission, History

Early in its constitution, the CCCC branch of the NCTE Women’s Committee appeared to exist as a loose assembly of women who met for breakfast and were connected via a print newsletter. An early report (1978) opened with “4C’s Exchange: a newsletter conceived in the joy and enthusiasm of all 139 of us sharing …… listening ….. thinking ….. responding ….. laughing ….. planning at the Women’s Luncheon in Kansas City,” with references to a breakfast held the previous year in Philadelphia. As a grassroots group, there was no stated charge attached to the group, though the 1978 document (listing Anita Sheen, as chair; and Lou Kelly as the founder of the group) defined its focus as “…between connections, this newsletter, for exchanging our concerns and discoveries and accomplishments. For helping us take charge and work out the new concepts, the new styles and roles our frontier requires” (1). The earliest formal documentation is also found in a June 21, 1977 letter from, with the note that “Lou Kelly asked 4C’s officers to authorize a 4C’s Women’s Committee with members not to be designated by 4C’s chair. So we’re now an official component of a professional organization that really supports us” (1, emphasis original). However, later documents suggest that from the start, the desired work of the Women’s Committee was at cross-purposes with the organization, and elements of their work from its name to its structure were in passive aggressive tension. It’s worth recounting the June 21, 1977 letter in which Robert Hogan (then holding the title of Executive Secretary of NCTE) recognizes the development of the CCCC Committee on the Status of Women and his suggestion that there need not be such a committee. He writes:

One thing I don’t like about myself is that I put off doing the things I feel uncomfortable doing. But, damn them, they just won’t go away. So I’m taking up one of them in this letter. […] Although the officers of CCCC did authorize in principle the formation of a women’s committee under the aegis of CCCC, that’s all they did. Had I been alert during that part of the officer’s meeting, I would have asked for a delay. But what I thought was merely a report of a request relayed through Betty Renshaw, turned out, in Betty’s and Nancy’s notes, as a formal motion, seconded, and carried.

Robert Hogan notes as his concerns the difficulty the NCTE Committee on the Role of Women had in the beginning of its tenure, which he characterizes as “a call for volunteers without any battle plan;” a lack of money; a “duplication of effort”; and a lack of staff support. Despite these concerns, the CCCC committee was formed (June 21, 1977, “Letter to Lou Kelly”). The persistent, stealth advocacy represented by the work of “Betty’s and Nancy’s notes” exemplifies CSWP/FC work across its existence.

The first Charge to the NCTE Committee on the Role of Women in the Profession and Council is clearly mirrored in the CCCC CSWP. Their 1971 charge includes the following concerns:

- Salary schedules, promotions, administrative capacities.

- Representation on Council Commissions, Board of Directors and Executive Committee.

- Representation of women in material used in the teaching classrooms.

- Impact of women/men on children in the classroom: research.

- Awarding of grants, fellowships, awards to promising women in the English profession.

- Self-image and attitude.

- Discriminatory practices in any area involving sex differentiation.

- Sources or lack of sources available for child day care so that women with children can successfully pursue graduate study and/or half or full time teaching.

- Nepotism rules that prohibit married couple teaching on the same faculty.

Clearly, labor conditions, representation, and the impact of personal conditions on professional experiences is focal from the CSWP/FC’s beginnings. The CCCC Committee on the Status of Women was convened in 1983 with the following charge:

To review the status of women in the profession, especially women who identify themselves with the aims of CCCC; to continue to promote the participation of women in the annual convention, on CCCC committees, and in positions of leadership within CCCC; to keep the officers and membership of CCC advised of the concerns of women; to cooperate, when appropriate with the NCTE Women’s Committee in recommendation policies and actions affecting the status of women; to initiate, respond to and/or implement projects of special relevance to women; and to recommend appropriate political and financial actions when, in the future, Congress passes a new constitutional amendment supporting equal rights for women. (Letter to John Bodnar from Don Stewart, July 28, 1983).

The next available formal report to CCCC (of the C’s-specific group) is in 1987, which states that its purpose is to “attempt to promote greater solidarity and communication among women in the CCCC,” with a reference to a goal of educating new women faculty about career and scholarly development.

Over the next half dozen reconstitutions and recharging of the group, the activities and focus of the group evolve, whereas the early charge focused primarily on support and solidarity, the 1993-1996 charge assigns the following: “This committee will identify specific projects it might undertake to 1) develop a coalition to represent the needs and interests of all women in CCCC, with special attention to the diversity represented by these women; and 2) address specific issues, such as sexual harassment, that affect women disproportionately.” This charge was extended for the 1997–1999 and 2001–2004 reconstitution.

In 2005, however, the charge is adjusted with a historical focus. The new charges initially read (for the 2005–2008 term):

“Charge 1: To review the history of CCCC, with respect to its activities on behalf of women, for purposes of historical recording: what activities were undertaken, and what did they contribute to the CCCC and to its women members?

Charge 2: To share the historical record in appropriate venues.

Charge 3: To identify continuing woman-gender specific concerns that should be brought to the attention of the members for reasons of scholarship and/or action; to recommend appropriate actions to the officers and the EC.”

And then, after just a year of composition, the committee requests that the language of Charge 3 be revised to read, “To identify feminist concerns and continuing woman-gender specific concerns that should be brought to the attention of the members for reasons of scholarship and/or action; to recommend appropriate actions to the officers and the EC.” The charge continues to emphasize feminist and women-specific areas of interest, while emphasizing a passive or received set of activities; that is, the group is charged with “reviewing” and “sharing” as well as “identifying” issues and concerns, which are then necessary to take to other leadership and governance groups to act on.

A distinct shift takes place in the 2014–2017 charge, reflecting the desire throughout the group’s history to have more agency and self-determination about a) its work, b) the outcomes, and c) acting on and creating change on the basis of their work. It also reflects a more inclusive shift mirrored in gender studies, to feminist concerns, rather than gendered concerns. The 2014-2017 charges read as follows:

“Charge 1: Identify feminist questions, concerns, and points of inquiry within the field of rhetoric and composition in areas of relevance to CCCC members and the profession at large

Charge 2: Lead appropriate forms of inquiry into feminist concerns in the field of rhetoric and composition with the goal of proposing solutions, taking a position, or generating action items

Charge 3: Make recommendations to CCCC Officers and Executive Standing Group based on inquiry, examination, or CSWP.”

Though there is still an emphasis on “identifying,” the language focuses on feminist questions, concerns, and points of inquiry, while charge 2 includes the verb “lead” and links that inquiry leadership to the “goal of proposing solutions, taking a position, or generating action items.” The structure of the group, however, is limiting in the sense that the group itself is not empowered to bring about large scale structural or fiscal changes in the priorities of the organization. As this overview of the evolving charge shows, the more heavily unidirectional channels of direction that distinguished the group’s work in the first three decades meant that the group was empowered to identify priorities and projects, but only some were fully accomplished or achieved traction within the organization.

Evolution of the Coalition: Purpose, Mission, History

While not charged as a CCCC task force, the Coalition’s evolutions in purpose, mission, and history appear to be member-driven. One way of marking its evolution is by drawing attention to five types of organizational movement we see evidenced in the archives: constitution creation and bylaws revisions (the latter revisions occurring at least four times between 2007 and 2022); conference formation and Action Hours; journal formation; non-profit status; and webinars. In Lifting as We Climb, a retrospective documentary celebrating 25 years of the Coalition’s existence, inaugural president Kathleen Welch traces the immediate exigence for the group as a four-hour phone conversation. Over the phone, Welch and her colleague considered the shared difficulty they saw women colleagues in the profession having in being awarded tenure, “no matter how hard they [worked].” They agreed that they needed a venue to address this and similar concerns and to work towards bringing visibility to research on and by women in the history of Rhetoric and Composition, and to mentor women new to the profession. As Andrea Lunsford succinctly remembers: “more about women, more about women.”

The constitution was co-written by the original executive board members: Kathleen Welch, the late Winifred Bryan Horner, the late Nan Johnson, Marjorie Curry Woods, and the late C. Jan Swearingen, and the first public meeting of the Coalition occurred during a specially designated slot on Wednesday evening just prior to the annual CCCC in the early 1990s. (Some accounts date 1990, while others cite 1993. For the purposes of this article, we acknowledge that the group began meeting as an organized caucus from 1990 forward). Feminist scholar Carol Mattingly, then a graduate student, recalls attending the meeting as a newcomer, and both she and the organizers were disappointed at the lack of turnout. Because only a few participants showed up, the organizers left for dinner. However, membership grew as the Wednesday evening event included “mentoring tables,” an outgrowth of the original mission intended as a space for political action for women (Welch). Soon, membership dues were regularly collected, and the Peitho newsletter, edited by Susan Jarratt and Kay Halasek, began to circulate in 1996 (“Letter”).[10] In 2007, after several rounds of drafting, a set of bylaws consisting of seven articles became the organization’s governing document, outlining in more detail the names, offices, purposes, and membership of the organization, and formally establishing election protocols and terms of office that would ensure rotating membership among both Executive and Advisory Boards (“Bylaws”).

In 1997, the Coalition co-sponsored the first biennial Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference at Oregon State University, co-chaired by the late Lisa Ede and Cheryl Glenn, with plenary addresses offered by Jacqueline Jones Royster, Barbara Warnick, Joy Ritchie, Patricia Sullivan, Angeletta Gourdine, Susan Jarratt, Nancy Tuana, Andrea Lunsford, Susan Brown Carlton, Arabella Lyon, Shirley Logan, and Krista Ratcliffe. As past presidents Cheryl Glenn, Shirley Logan, Kate Adams, and Lynée Gaillet recall during their vignettes in “In Their Own Words: The History and Influences of the Coalition,” putting new and emerging scholars on stage alongside more senior scholars had been an inherent goal of the plenaries at the annual CCCC caucus event (Eble and Sharer; Ramsey-Tobienne and Graban).[11] Thus, providing additional space and visibility for nurturing feminist scholarship in Rhetoric and Composition through a dedicated conference, where emerging and seasoned scholars could listen and learn alongside one another in an intimate setting over one long weekend, was another extension of that goal.

One of the primary successes for the Coalition was transitioning Peitho from an online newsletter first circulated in 1996, to a peer-reviewed journal first re-released in Fall/Winter 2012 (“CWSHRC Board Meeting”), a change that aligned with their values to recognize and amplify women’s scholarship and to support forward progress toward tenure. After three revisions of its development proposal, in 2011 a specially appointed ad-hoc committee successfully laid out plans to convert the newsletter into a biannual peer-reviewed journal, suggesting a new journal structure, a budget, a set of bylaws, and an organizational structure that included a publication committee, an editor, an associate editor, and an editorial board (“Peitho Development”). As a web-based open-access publication, Peitho publishes four times a year, and in the 2021 editors’ report, the journal had received more than 30 submissions that year.

By 2010, the Coalition had met its long-term goal of gaining non-profit status, a structure that allows them to do more fundraising, solicit tax-free donations, and distribute scholarships, travel grants, and awards (“Strategic Plan”). This change in status preceded another of the Coalition’s more significant evolutions: the group’s name change from “Women Scholars” to “Feminist Scholars” in 2016, in part to reflect the gendered inclusivity already promoted by the group, and in part to un-gender the group’s mission and goals. Inclusivity has remained a central focus for the Coalition since then, much of it occurring as a result of stated or expressed needs by the membership, many of whom represent neurologically diverse, nonbinary and trans identities; many of whom do work that is informed by social justice pedagogy; and many of whom prioritize the enfranchisement of scholars of color, graduate students, and NTT or contingent faculty. These initiatives are marked more recently by the Coalition’s retrospective on the challenges of claiming intersectional work (Graban et al); by its “Advancing the Agenda” webinar series, initiated during the COVID-19 pandemic in lieu of the 2021 Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference; by the development of a Shared Values Statement at CCCC 2022; and by the official integration of graduate students into leadership roles on both the Executive and Advisory Boards.

Early leaders in the Coalition historically expressed interest in taking their work “beyond the academy,” intending, as Andrea Lunsford reminds us in Lifting As We Climb, to “carve out a new public understanding of the role women might play,” a goal that aligns with the equity work that orients the Feminist Caucus’ plans. While Coalition meeting agendas as early as 2006 indicate webinars as a venue for this public outreach, it isn’t until 2021 that a formal webinar series gets initiated, partly in response to the 2021 CCCC remote conference (“Event”), partly as an alternative venue for the 2021 Feminisms and Rhetorics conference (“Online Event!”), and partly in response to organizational critiques that the Coalition’s anti-racist agenda could be made more visible. At the Spring 2022 annual business meeting, the Executive and Advisory Boards voted to continue this “Advancing the Agenda” webinar series for 2022–2023 (“Advisory”).

Intersections of CSWP and Coalition

Although they have evolved to address many of the same intersectional feminist concerns in RWS, and although CCCC marks as the primary meeting space for both entities, one of the primary elements that stands out in differentiating their histories is the way in which each group has developed and been sustained over many decades. Whereas the CCCC Feminist Caucus developed within an established organization as a way to inform the organization and (perhaps) reform it from within, the Coalition developed on its own terms as a response to a perceived absence of spaces for addressing feminist concerns within the discipline. In this way, the two groups offer different pathways for addressing concerns and highlight the various challenges associated with each path. There has been cross-pollination of people and ideas across the Caucus and the Coalition for decades, particularly manifesting in participation in the Women’s Network SIG, the Feminist Workshop, and the Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference, and publishing in Peitho. Notably, there is less observed overlap in leadership, although this observation deserves to be revisited as new material is submitted to the archives.

The first explicit Coalition-Caucus collaboration we see in our archives is a 2003 session at CCCC entitled “Electric Rhetoric.” Then, the two groups co-sponsored mentoring SIGs at the 2004 CCCC. In the following decade the groups’ work overlapped in their respective venues, with the Committee-sponsored Women’s Lives in the Profession Project taking center stage with the DALN at the 2011 Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference, and Peitho publishing the results of the Committee’s Service Mapping Project, “Key Concept on Service.”

The Coalition continually marshaled their considerable social media networks to amplify Feminist Caucus work, and once the Feminist Caucus Business Meeting was opened broadly as a result of their Standing Group status, they encouraged participants to attend Coalition events. In 2019, when the three of us were Chairs of the respective groups, we began exploring opportunities for collaborative feminist work in the discipline. The Feminist Caucus created an informational blogpost for the Coalition website (Hassel and Pantelides), Feminist Caucus Co-Chairs attended the Feminist Rhetorics 2019 business meeting, and created a brief slideshow detailing Feminist Caucus information and photos for display during the conference. Further plans for collaboration at the 2020 CCCC were foiled by the pandemic. Yet, in tracing our organizational work alongside each other across the decades, and now facing familiar conversations regarding inequity, lack of support for caregivers, workplace harassment, attacks on academic freedom, and reproductive rights, we are doubly encouraged to consider what we might be able to accomplish together as a feminist body.

Inclusivity, Diversity, and Community

Though some effort throughout the history of both groups was paid to coalition-building with other groups who had a shared investment in social justice and equity, both structural challenges and white and class privilege interfered with those aims. Early documents, for example note that the NCTE Women’s Committee co-sponsored “a workshop in New York with the Task Force on Racism and Bias, the Minority Affairs Committee, and the Council on Interracial Books for Children” (6-9-1977, letter from Lallie Coy (Chair) to the Members of the Committee). However, the committee structure (which by the mid-1980s was relatively formalized within the organization) operated as a governance body of CCCC and not as an open group; likewise, the Women’s Network SIG which was held starting in 1996 at the annual convention was scheduled like most SIGs, concurrently during four dedicated slots (6:30–7:30 pm and 7:30–8:30 p.m. on the Thursday and Friday of the conference). This means that attendees often had to select the special interest group meeting they wished to attend, creating barriers for participation in multiple groups, a factor repeatedly brought up as a concern in committee reports. Because of these organizational limitations, of the various CSWP/FC opportunities, the Feminist Workshop was perhaps best able to consistently reflect and sponsor the diverse work and membership of feminists in RWS, as noted in the CSWP/FC charge, throughout its existence.

In addition, though the stated aim (and charges) throughout the group’s work beginning in 1983 as a special committee focused on equity, diversity, inclusion, and the status of women within the field, little direct and specific attention is visible in the documents that report on the groups’ work, and their efforts at feminist advocacy were not explicitly intersectional, let alone prioritizing issues of importance to women of color. In the 1980s, in particular, the priorities of the group included a single-axis focus on gender with no consideration of other issues (as was often the case in feminist advocacy work at that time). For example, the “Questionnaire: CCCC Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession,” circulated by the group through a variety of channels questions about institution type; gender of faculty leadership; proportion of women and men at various ranks and employment status; and methods of recruitment; but there are no questions related to other identity categories such as race or ethnicity that might help disaggregate the responses and pinpoint issues of specific value to women of color. Priorities that show up through the 1980s include nonsexist language, the visibility of women’s scholarship and women’s writing (for example, in the form of requesting categories on the convention program guide on ‘women and writing’ and emphasis on nonsexist language efforts without an accompanying emphasis on antiracist language practices).

Yet, despite the repeated stated interest in selecting a representative committee, there are numerous points in the Feminist Caucus’ history in which the committee was entirely composed of white women. Further, though the Caucus-sponsored events, the Feminist Workshop and the Women’s Network SIG, were open to CCCC membership, the Business Meeting was closed to members selected by the CCCC EC until the change to a Standing Group structure in 2016. The CCCC Executive Committee selected members for the committee and suggestions for committee members were taken as recommendations. For instance, in 2009, Eileen Schell noted, “We would like to expand the racial and ethnic diversity of our committee. We have a great group of women on the committee who represent varied institutions and career paths, but we are now a completely white committee… We have no representation of Asian, Latina, and Native American women faculty on this committee and have not in recent memory…We realize that we cannot just add members, but we do encourage the EC and the CCCC officers to consider how our committee membership might be diversified.” Thus, the repeated interest in creating a more inclusive Caucus by changing the structure of the group was not realized for decades. As a result, the work of the committee did not necessarily meet the broader needs of faculty across RWS.

Likewise, the Coalition has similarly sought to increase inclusivity, and fostering a climate that invites participation has also been a goal intermittently realized for the Coalition, with work both behind and ahead. From what we have observed in the archives, the achievement of a dedicated spot on the CCCC pre-conference program, traditionally Wednesday evenings from 6:00–8:00 p.m., did help to raise visibility of the organization at that conference for those who could arrive and attend early. Even still, like many feminist organizations, a recurring challenge for the Coalition has been to fully center the diversity of its membership in the structures and programming of the group. In her interview for Lifting As We Climb, Joyce Middleton cautioned the group about “whiteness taking over,” indicating that the marked identification of the group had changed since her early involvement. This remark would foreground the organization’s renewed efforts to address the marginalization of members of color in the late 2010s. Other initiatives the Coalition has committed to, for example, include a standing group on graduate student engagement, Wednesday night mentoring events at CCCC accompanied by deliberate attempts to feature graduate students and new scholars or new faculty, primarily because their work hadn’t been featured in other venues, and ensuring that contingent faculty, independent scholars and unaffiliated scholars feel enfranchised to participate.

The Fem/Rhet conference themes have historically aligned with the organization’s priorities, from the earliest convention focused on “From Boundaries to Borderlands” to themes centering on “Intersections,” “Diversity,” “Complexities” and “Activism.” Following challenging critiques from marginalized scholars, including graduate students and early career attendees, about keynote events at the 2019 Fem/Rhet conference and the need for more accessible conferencing practices, the Advisory Board of the Coalition again actively grappled with the issues that were raised. For example, at a session facilitated by Coalition leaders at the virtual Watson conference in 2021 (whose theme itself was “Toward the Antiracist Conference: Reckoning with the Past, Reimagining the Present”), participants focused on the following:

In March of 2020, the Advisory Board of the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition voted to cancel the 2021 Biennial Feminisms and Rhetorics (FemRhet) Conference. This decision was made in light of COVID, but, more significantly, it reflected long-standing (and growing) concerns about the inclusivity of the conference. Concerns about the whiteness of conference programs, concerns about the costs of attending (for graduate students in particular), and concerns about the inaccessibility and exclusionary histories of the places and spaces within which the conference had been held all contributed. (“Intersectional”).

The summer resolution, “That the Coalition delay of the re-release of the call for 2023 Feminisms and Rhetorics site hosts until the spring of 2021 and require within this call that potential site hosts front themes of anti-racist activism and center the work of feminists of color” (Sharer) served as a touchstone to direct subsequent governance, values, and process work to engage in rigorous self-examination.

Conclusion

It is difficult to evidence change. As Nancy Prichard, Assistant Executive Secretary of NCTE noted in 1970 regarding the creation of the NCTE Committee on Women, “Obviously, the only conclusion for this memorandum is that women’s work is never done.” Similarly, these brief overviews of the work of the CSWP/FC and the Coalition underscore that feminist work in RWS is never done, and it seems likely we’re on the cusp of a moment in which feminist work is more important than ever. In fact, as this article goes to press, we acknowledge national protests over the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe vs. Wade, reminding us that the history of how women and underrepresented members of RWS have been included in or excluded from certain opportunities in the field, and—more importantly—how they have navigated those inclusions and exclusions with one another, is still what drives us.[12] As each organization performs its response to the decision, we recognize how this and all related conversations are frustratingly reminiscent of the 1970s discussions that laid the groundwork for the CSWP and the systemic tensions from which the Coalition was eventually born. We are also reminded of some important distinctions between our groups.

The CSWP/FC has always prioritized the material and practical realities of women’s lives (employment equity, childcare, composition classroom, bias/harassment/bullying), and their large scale research projects have often sought to quantify inequity to build arguments for better institutional resources, both from CCCC as an organization and for feminists to use at their own institutions. Created grudgingly by the CCC EC as an offshoot of work in NCTE, modeled on work in MLA, the CCCC Committee on the Status of Women tried “to acknowledge the impact of [feminist energy and commitment…], channel …humanistic power…, [and] assert a founding momma’s right to defer to the energy and vision of the Young.” In this way, the CSWP/FC demonstrates efforts to do feminist work within an organization, and the various difficulties associated with that work.

The Coalition demonstrates efforts to do feminist work outside an existing organization, to create both inter- and intra-disciplinary spaces for doing feminist work. As Kathleen Welch notes in Lifting As We Climb, she and the founding members of the Coalition were fed up with women colleagues not getting tenure and not having their work recognized, both inside and outside of the classroom. They found strength in organizing outside of their institutions, outside of the existing disciplinary organizations that were, in many ways, reifying the problems they experienced at their home institutions. At the same time, this para-organizational stance has, in certain historical moments, contributed to confusion about the positioning, identification, and responsibilities of the group.

The archives of both entities show an evolution responsive to members’ needs, thus mirroring the needs of whichever members are most active at the time. The CSWP/FC does make changes within the organization that reflect the members’ and partner groups’ consistent requests, perhaps most notably in the organization’s financial commitment to providing dependent care grants, and, after nearly five decades of requests, fundamental changes to the convention and committee structures. The CFSHRC’s Advisory Board agendas, meeting minutes, and public blog posts indicate that they, too, expect development beyond the goals and ideas of their founders. And both entities have developed in response to tensions within the discipline—including disagreements about where scholarship and public activism did and should intersect, about invisibility, and stultifying patriarchal structures. Both have identified different structures for outreach.

Of course, as with any archival project, there are many stories we could tell, should tell, and hope to tell at some point. There are also stories that these archives cannot tell. As familiar as we are with our respective organizations, performing this archival trace only complicated our understanding of how the groups are similar and different. In fact, our trace has raised questions about how current understandings of feminist work in the discipline might spur us to encourage future collaborations amongst the two groups, but also—and somewhat surprisingly—about whether and how the groups can and should work together moving forward. How can each group serve its diverse memberships, sustaining, as the Coalition writes in its mission statement, “all who do feminist work, inclusive of all genders, sexualities, races, classes, nationalities, religions, abilities, and other identities, in their research and classrooms”? With charges this vital, how can each group make its distinctive spaces more welcoming and more attractive for feminist members of cultural, ethnic, or religious groups that are bound by professional or community politics and who necessarily operate outside of a Eurocentric framework? Moreover, how will each group work independently and together to make room for disagreement and discord? Until those questions are answered, our archival work continues.

We write with the conviction that our institutions and the discipline writ large have benefited from intersectional feminist work, and that the advocacy and mentoring efforts that have characterized the CSWP/FC and Coalition have made a difference, even as we are made aware of how those organizations have not addressed all the needs. Yet going forward, we do not recognize a single successful blueprint for organizational feminist praxis. Whether our readers in RWS choose to adopt stealth advocacy practices—like Betty and Nancy, the founders of the CSWP—or whether they get fed up and create their own new spaces for our work—like Kathleen Welch and her colleagues—we hope they will reflect on these practices as we have done, and consider the unique challenges of building feminist community, past, present, and future. Moreover, we hope readers find this archival tracing useful for charting possible intersections of each group’s motives and methods, for identifying points of productive disagreement and discord, and for identifying other ways to respond to new calls to focus on activism, labor, scholarship, teaching, and being in the academy.

End Notes

[1]The group was initially activated as the CCCC Women’s Committee and then operated for many years as the Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession.

[2]The group was known until 2016 as the Coalition of Women Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, founded in 1989 as a CCCC affiliate, alternatively referred to as a Caucus or Special Interest Group.

[3]Anecdotally, we have heard some scholars who have participated across these organizations wonder aloud whether their separation is meaningful, intentional, or, as a colleague questioned more pointedly: “Was there some sort of schism?”

[4]See “Women’s Committee 1977.” 15/74/3: Conference on College Composition and Communication Administrative Subject Files, 1944-2006. Box 12. National Council of Teachers of English Archives. University of Illinois, Champaign, IL.

[5]A Wikipedia article, citing Richard Nordquist, reports the group’s founding as 1988 (“Feminist”), though the Coalition’s archives situate its initial organization at the end of the 1989 academic year, and its formal founding in 1990. At different points in its history, the CFSHRC sought affiliation with the Modern Language Association, the Rhetoric Society of America, and the Alliance of Rhetoric Societies, before the latter group’s dissolution in 2011 (Myers).

[6]To wit, until construction of the first finding aid was begun by Alexis Ramsey–Tobienne, the task of searching through the Coalition’s digital archives was daunting. While much of the organization’s activity is documented in various e-mail chains, agendas, meeting minutes, and newsletters, the Coalition’s blog (/blog/) offers a more publicly accessible way of reading into the organization’s activities—at least since 2012, with most blogging activity picking up in 2014 after the first redesign of the organization’s website, and again in 2020 after the second reconstruction of its website. The organization’s original two sites were pulled down by Susan Romano (University of New Mexico) in 2008, at the request of the Advisory Board (“CWSHRC Board Meeting”).

[7]It should be noted that Peitho and the Feminisms and Rhetorics conference have their own histories that are necessarily flattened in this brief archival trace.

[8]Other members included John P. Bodnar (Prince George’s Community College), Lynn Bloom (Virginia Commonwealth University), Sylvia Holladay (St. Petersburg Community College), and Neil Nakadate (Iowa State University).

[9]“Standing Groups are member-organized coalitions approved by the CCCC Officers. Standing Groups begin as Special Interest Groups and may apply for SG status after fulfilling the requirements outlined for that status. Standing Groups define their own mission and charges in conjunction with the broad mission and vision of CCCC” (https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/about/constitution).

[10]From 2002–2006, Jarratt co-edited the newsletter with Susan Romano. In 2009, Barb L’Eplattenier assumed editorship through its 2012 transition to a journal.

[11]This goal was further corroborated by the evolution of the pre-CCCC Wednesday evening caucus event into “action hours,” beginning in 2015 with the “New Works Showcase” that reconfigured the platform talks into interactive poster sessions (Adams et al) or action tables (“Join Us”).

[12]See, for example, the CFSHRC’s “Statement on the Overturning of Roe vs. Wade,” reflecting the organization’s tradition of composing and circulating statements of advocacy to support the mobilization of its members.

Works Cited

Adams, Heather B., Erin M. Andersen, Geghard Arakelian, Heather Branstetter, Lavinia Hirsu, Nicole Khoury, Katie Livingston, LaToya Sawyer, Erin Wecker, and Patty Wilde, with Trish Fancher, Tarez Samra Graban, and Jenn Fishman. “From Installation to Remediation: The CWSHRC Digital New Work Showcase.” Peitho, vol. 18, no. 1, Fall/Winter 2015. /article/digital-new-work-showcase-presentations-from-the-coalitions-session-at-cccc-2015/

“Advisory Board Meeting Agenda.” 9 March 2022. TS. CFSHRC Digital Archives, AB_meeting_agenda_3-9-2022.

Adichie, Chimamanda. “The Danger of a Single Story.” TED Global, 2009.

Almjeld, Jen, and Traci Zimmerman. “Invaluable but Invisible: Conference Hosting as Vital but Undervalued Intellectual Labor.” Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, vol. 4, no. 2, Winter 2021, http://journalofmultimodalrhetorics.com/4-2-issue-almjeld-and-zimmerman

“Annual Advisory Board Meeting Minutes.” 6 April 2016. TS. CFSHRC Digital Archives, AB_meeting_minutes_4-6-2016.

“Bylaws of the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition.” Updated March 2022. /docs/peitho/files/2022/04/CFSHRC-BYLAWS-revised-3-2022.pdf

“Call for Site Hosts: 2023 Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. July 2021. /exciting-feminisms-and-rhetorics-news/

Conference on College Composition and Communication. “Constitution of the Conference on College Composition and Communication of the National Council of Teachers of English.” https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/about/constitution

CCCC Status of Women Reports and Governance Documents. Received from the NCTE archives at University of Illinois, Champaign, IL, and via Kristen Ritchie at the CCCC office. https://www.dropbox.com/sh/1pel9xov5x6rlx6/AAAnBBCiE1U5_tZ_x0yyWvC4a?dl=0

CCCC Feminist Caucus. “CCCC Feminist Caucus: It’s Time to Bring the F-Word Back.” https://sites.google.com/view/feministcaucus/home.

—. “Feminist Workshop.” https://sites.google.com/view/feministcaucus/feminist-workshop.

“CFSHRC Statement on the Overturning of Roe vs. Wade.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. 1 July 2022. /cfshrc-statement-on-the-overturning-of-roe-vs-wade/

Cole, Kirsti. and Holly Hassel. Surviving Sexism in Academia: Strategies for Feminist Leadership. Routledge, 2017.

Clary-Lemon, Jennifer. “Archival Research Process: A Case for Material Methods.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 33, no. 4, 2014, pp. 381–402. Web. 16 Dec. 2016.

“Count ‘em: 5 New CWSHRC Opportunities!” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. 15 October 2014, /scholarly-opps/.

“CWSHRC Board Meeting at CCCC.” 2 April 2008. TS. CFSHRC Digital Archives, Minutes_CCCC_2008.

Detweiler, Jane., Margaret LaWare, and Patti Wojohn. “Academic Leadership and Advocacy: On Not Leaning In.” College English, vol. 79, no. 5, 2017, pp. 451–65.

Eble, Michelle F, and Wendy Sharer, eds. In Their Own Words: The History and Influences of the Coalition. Produced 2008, re-mastered 2014.

“Event: ‘Art in the Time of Chaos’ Featuring Alexandra Hidalgo.’” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, 25 March 2021. /event-art-in-the-time-of-chaos-featuring-alexandra-hidalgo/

“Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference Hosts for 2023 and 2025.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. 11 April 2022. /feminisms-and-rhetorics-conference-hosts-for-2023-and-2025/

“Feminist Rhetoric.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. 12 June 2022. 15 July 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminist_rhetoric.

Fishman, Jenn. “Volunteer to Mentor a CWSHRC Scholar.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. 9 September 2014. /volunteer-to-mentor/

Gindlesparger, Kathryn Johnson. “Trust on Display: The Epideictic Potential of Institutional Governance.” College English, vol. 83, no. 2, 2021, pp. 127–46.

Glenn, Cheryl. Rhetorical Feminism and This Thing Called Hope. Southern Illinois UP, 2018.

Graban, Tarez Samra. “Expanded Mentoring Program Begins!” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. 19 October 2020. /expanded-mentoring-program-begins/.

Graban, Tarez Samra, Heather Adams, Jenny Unghba Korn, Lana Oweidat, Sarah Singer, and Jen England. “Re-Examining Intersectionality in Our 30th Year: A Remediation of the 2019 CFSHRC Action Hour.” Peitho, vol. 22, no. 1, Fall/Winter 2019. https://actionhour2019.cfshrc.org/

Hassel, Holly and Kirsti Cole, eds. Academic Labor beyond the Classroom: Working for Our Values. Routledge, 2019.

Hassel, Holly and Kate Pantelides. “Writing Our Future: Feminist Collaborations between CCCC Feminist Caucus and the Coalition.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. 2 December 2019. /writing-our-future-feminist-collaborations-between-cccc-feminist-caucus-and-the-coalition-2/

Hidalgo, Alexandra. “Lifting as We Climb: The Coalition of Women Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition 25 Years and Beyond.” Peitho Journal, vol 18, no. 1, 2015. /article/lifting-as-we-climb-the-coalition-of-women-scholars-in-the-history-of-rhetoric-and-composition-25-years-and-beyond/

“Intersectional Imperatives: Steps toward an Antiracist and Inclusive Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference.” Watson Conference. Conference Schedule. 22 April 2021.

“Join Us for Our 4C17 Event: Building Sustainable, Capable Lives, or Tilting at Windmills?” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. 10 February 2017. /join-us-for-our-4c17-event-building-sustainable-capable-lives-or-tilting-at-windmills/

“Letter from the Editors.” Peitho: Newsletter of the Coalition of Women Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, vol. 1, no. 1, Fall 1996, p. 1.

Mastrangelo, Lisa. “Welcome to the Coalition of FEMINIST Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, 16 May 2016. /welcome-to-the-coalition-of-feminist-scholars-in-the-history-of-rhetoric-and-composition/.

“Mentoring.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. /mentoring/

Meyers, Nancy. “Coalition of Women Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition Advisory Board Meeting Agenda.” 6 April 2011. TS. CFSHRC Digital Archives, AB_agenda_CCCC_apr2011.

“Mission.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. /about-us/#mission.

“Online Event! ‘Let’s Talk about Mentoring: A Feminist Approach to Compassion and Care in Academic Spaces.’” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, 22 October 2021. /online-event-lets-talk-about-mentoring-a-feminist-approach-to-compassion-and-care-in-academic-spaces-tues-9-9-4-530-pm-est/

“Past Presidents’ Gallery.” Part of “A Remediation of the 2019 CFSHRC Action Hour.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. https://actionhour2019.cfshrc.org/30th-anniversary/past-presidents-gallery/

“Peitho Development Proposal, Version 3.” 16 October 2011. TS. CFSHRC Digital Archives, 2011_10_proposal_final.

Pettus, Mudiwa. “Announcing the Fellowship Pods Program.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, 7 June 2021. /announcing-the-fellowship-pods-program/

Price, Margaret. “The Bodymind Problem and the Possibilities of Pain.” New Conversations in Feminist Disability Studies. Spec. issue of Hypatia, vol. 30, no. 1, 2015, pp. 270–84.

Ramsey-Tobienne, Alexis E., and Tarez S. Graban. “‘Lifting As We Climb,’ Since 1989.” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. 2019. /history-in-film/

Rice, Jenny. Awful Archives: Conspiracy Theory, Rhetoric, and Acts of Evidence. Ohio State UP, 2020.

Royster, Jacqueline Jones, and Gesa E. Kirsch. Feminist Rhetorical Practices: New Horizons for Rhetoric, Composition, and Literacy Studies. Southern Illinois UP, 2012.

Sharer, Wendy. “Exciting Feminisms and Rhetorics News!” Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition. 9 July 2020. /exciting-feminisms-and-rhetorics-news/

“Strategic Plan. Coalition of Women Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition.” 8 October 2005. TS. CFSHRC Digital Archives, AB_peitho_development_plan_2005.