Coalition Building Between Subjectivity and Instrumentality: Reflecting on My Experiences in a Militant, Trotskyist Women’s Rights Group in the 1990s

Coalition Building Between Subjectivity and Instrumentality: Reflecting on My Experiences in a Militant, Trotskyist Women’s Rights Group in the 1990s

Peitho Volume 26 Issue 1, Fall 2023

Author(s): Don Unger

Don Unger (he/him/his) is the McCullough-Greer Assistant Professor of Civic Writing in the Department of Writing, Rhetoric, and Speech Communication at the University of Mississippi, where he is also affiliated faculty with the Gender Studies and Community-Engaged Leadership programs. His work focuses on community writing and publishing and includes serving as an editor of Spark: A 4C4Equality Journal. His academic work has been published in Computers and Composition, Constellations: A Cultural Rhetorics Publishing Space, Community Literacy Journal, Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, and Teacher-Scholar-Activist, among others.

Abstract: This article contributes to conversations about how coalitions shape relationships among people dedicated to social change by reflecting on some of the author’s experiences in the mid-1990s with the National Women’s Rights Organizing Coalition (NWROC)—a militant, Trotskyist, women’s rights organization. In this article, he notes that feminist and queer/Latinx scholarship and Trotskyist approaches depict coalition building in similar ways. They agree that coalitions bring together groups of people with diverse perspectives in order to take joint action around an issue, and they support building coalitions through temporary alliances and ongoing relationships. However, they raise different questions about when a group ceases to be a coalition and becomes something else, and why that matters. Guided by this discussion, he reflects on his experiences with NWROC, highlighting his concerns about their approach. In the end, he offers some considerations for teacher-scholar-activists engaged in coalition building.

Tags: activism, coalition, temporary alliance, TrotskyismIntroduction

This article contributes to conversations about how coalitions shape relationships among people dedicated to social change by reflecting on some of my experiences in the mid-1990s with the National Women’s Rights Organizing Coalition (NWROC)—a militant, Trotskyist, women’s rights organization. In this article, I note that feminist and queer/Latinx scholarship and Trotskyist approaches depict coalition building in similar ways. They agree that coalitions bring together groups of people with diverse perspectives in order to take joint action around an issue, and they support building coalitions through temporary alliances and ongoing relationships. However, they raise different questions about when a group ceases to be a coalition and becomes something else, and why that matters. Guided by this discussion, I reflect on my experiences with NWROC, highlighting my concerns about their approach. In the end, I offer some considerations for teacher-scholar-activists engaged in coalition building.

Feminist and Latinx/Queer Approaches to Coalition Building

To contribute to ongoing conversations about the term coalition and attendant strategies for building them, I begin by tracing some of the ways that the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition (the Coalition) use it, noting that its use is entangled in the organization’s thirty-year history. Briefly examining this history and the shifting use of the term helps me consider why feminist and queer/Latinx scholarship on coalition building and Trotskyist approaches differ regarding the kinds of relationships that coalitions build.

Since its inception in 1989, the Coalition has long grappled with both its mission and putting this mission into practice by growing the Coalition and expanding the resources that it offers members. At times, these conversations have made it into Peitho or been included in blog posts published to the Coalition’s website. For example, special issue editors Jessica Enoch and Jenn Fishman coordinated Peitho volume 18.1 in 2015, which offers reflections on the Coalition and its trajectory for its 25th anniversary. Written by long-standing members and leaders, these reflections include “key concept statements.” Cheryl Glenn and Andrea A. Lunsford contributed a statement on the term “coalition,” which begins with a discussion of why the word appears in the group’s name. In the statement, Glenn and Lunsford advance the notion of a coalition as “…a group of distinct individuals who come together to cooperate in joint action toward a mutual goal (or set of goals)—not forever, but for however long it takes” (11). The Coalition serves as a bridge “across differences in academic rank and standing (including students), institutional type, research agendas, teaching interests, and cultural ethnic/backgrounds” (11). Further, they use their definition to argue that expanding the Coalition means “being mindful once again of the importance of difference and of listening long and hard to those with whom we wish to join causes” (12). For the authors, expansion relies on a theory of coalition building and a strategy for building them where relationships among members and potential allies are depicted as paramount.

Other work published by Peitho that deals with building the Coalition grapples with the impetus behind the organization and the steps that have sustained it, including establishing governing bodies, task forces, and special committees as well as a structure for membership (Gaillet; Graban, et al.; Hidalgo); crafting internal policy documents like a constitution, by laws, strategic plans, and the like (Graban, et al.); moving Peitho from a newsletter to a peer-reviewed journal (L’Eplattenier and Mastrangelo); creating the Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference (Gaillet; Graban, et al.; Hidalgo); obtaining 501c3 status (Graban, et al.); reshaping the Coalition’s mission and subsequently renaming it (Bizzell and Rawson; Graban, et al.); and documenting CFSHRC’s long-standing relationship with the Conference on College Composition and Communication’s Feminist Caucus (Graban, et al). Based on these discussions, we see a clear focus on organizational structures as key to shaping relationships within the Coalition.

Returning to Glenn and Lunsford’s statement, they discuss the potential for the Coalition to expand internationally while also focusing on “inclusiveness at home” (12). This dual strategy speaks to both public outreach and internal restructuring. Within the Coalition, this move toward public work and the need to devote resources to intersectional initiatives has been discussed for decades. However, concrete steps toward these goals have only emerged in the past few years (Bizzell and Rawson; Graban, et al.). The Coalition has long provided a welcoming space for some feminist teacher-scholars of rhetoric and writing. By its own admission, it has disproportionately served white women (Graban, et al.). As some of the articles discussed previously attest, many of these folks consider it a “home,” a term Glenn and Lunsford use, as noted previously. How do these notions of a welcoming space or home inform the relationships that the Coalition has sought to build? Or more broadly, how might this perception of the Coalition as home skew coalition building?

Long-time civil rights and Black feminist activist and historian Bernice Johnson Reagon argues, “Coalition work is not work done in your home. Coalition work has to be done in the streets…It is very important not to confuse them—home and coalition” (359-360). Home is where you are nurtured, “so you better be sure you got your home—someplace for you to go so that you will not become a martyr to the coalition” (361).

Furthermore, Reagon warns that coalition building is dangerous work: “most of the time you feel threatened to your core and if you don’t, you’re not really doing no coalescing” (356). Sandra J. Bell and Mary E. Delaney might not call the coalition they write about dangerous, but it failed to coalesce and achieve its goals. In their experience trying to build a coalition of academics, community organizations, and government officials, participants’ different perspectives and ways of working meant that no one could agree on what a center grappling with domestic violence across Canada should do. Coalition members trace these disagreements back to differences in political agendas, professional benefits, financial motives, and other “instrumental goals” (65).

Deborah Gould grapples with the lasting impact of another coalition that failed to accomplish the goal that it organized around: preventing the gentrification of Chicago’s uptown neighborhood in the late 1990s and early 2000s. However, Gould argues that despite the coalition’s inability to make a lasting impact on gentrification in the area, it had a lasting, positive effect on participants. She notes that two groups that participated in the coalition, Queer to the Left and Jesus People USA, came to relate to one another in surprising ways. Where once they were foes pitted against each other on picket lines in front of abortion clinics, they became “strange bedfellows.” From this experience, Gould determines that “Coalition provides a space to be and do together, and become differently as a result; to sense other possibilities, open toward the unknown, experiment, and learn from mistakes; to develop trust and practices of solidarity; and to build new collectivities and new worlds.”

Gould’s assessment echoes Karma R. Chávez’s research on coalition building (e.g., Chávez, Queer Migration Politics; Chávez, “Counter-Public Enclaves”; Johnson, “The Time is Always Now”). Chávez argues that a coalition is “a present and existing vision and practice that reflects an orientation to others and a shared commitment to change” (Queer Migration Politics 146). Participants come together in what she calls coalitional moments that “might be a brief juncture or an enduring alliance” (Chávez, Queer Migration Politics 7, qtd. in Licona and Chávez 97). A “coalitional subjectivity” makes this coming together possible (Carrillo Rowe 10, qtd. in Chávez, “Counter-Public Enclaves” 3). As Chávez notes, adopting a coalitional subjectivity means moving “away from seeing oneself in singular terms or from seeing politics in terms of single issues toward a complicated intersectional political approach that refuses to view politics and identity as anything other than always and already coalitional” (“Counter-Public Enclaves” 3). This coalitional subjectivity doesn’t erase difference. Instead, participants come to “see issues, systems of oppression, and possibilities for a livable life as inextricably bound to one another” (Chávez, Queer Migration Politics 147). As Pritha Prasad notes, coalition is a continual and committed practice. This practice relies on relational literacies (Licona and Chávez, citing Londel Martin’s work, 96 and 104). Relational literacies refer to the labor it takes to make meaning across difference. These literacies “are never produced singly or in isolation but depend on interaction” (Licona and Chávez 96).

Gould, Chávez, Licona, and others point toward relationships as being at least part of the lasting change that comes from coalition building. Reconsidering the question of whether or not a coalition can be a home, I would argue perceiving it as such puts members or would-be allies at risk of being excluded from the coalition. While a coalition can certainly be more welcoming to some people than to others, it can also be rebuilt to make itself open to people and perspectives that have been excluded or ignored. It appears that the Coalition has begun moving away from conceiving of the organization as a home and toward a space where members might develop a coalitional subjectivity, at least in practice if not in parsing terms (Graban, et al.).

Trotskyist Approaches to Coalition Building

While traditions on the “old left,” including Trotskyism, might agree that coalitions exist to bring diverse groups together and carry out joint action and that these coalitions can be temporary or ongoing, they depict coalition building very differently. For starters, building a coalition is often focused on what participants can win against an adversary–the bourgeoisie– rather than on the relationships that would be created by the coalition among participants. While it is beyond the scope of this article to chronicle these differences in detail, I present a limited view into how Trotskyists approach coalition building because the organization that I discuss in the next section, NWROC, was composed largely of Trotskyists. His theories and writings informed their work even as other Trotskyist groups would undoubtedly say that NWROC’s work bore little resemblance to Leon Trotsky’s.

The “old left” says less about “coalitions” as such than contemporary academics do. Instead, they discuss “the united front” as a strategy for forming alliances among workers parties and organizations as well as unaligned workers. In a united front, participants make a joint agreement over a specific list of demands, however small or limited, to achieve a common goal or confront a common adversary (German). Trotsky traced the tactic back to the 1922 Resolutions on the Tactics of the Comintern, arguing that the united front was the building block of the Bolshevik-led Russian Revolution in October 1917. According to the document, only by drawing the mass of workers into struggle could the revolutionary party convince them of the accuracy of their political program. Additionally, the united front had a better chance of success because it drew on more social power than if a party or worker acted alone, of course.

After being exiled from Russia in 1927, Trotsky spent much of his life arguing for a united front between the social democratic and communist parties in Germany to quash the Nazis before they rose to power (German). Instead of coming together to fight the Nazis, German social democrats and communists fought one another. The dire circumstances surrounding Trotsky’s approach to coalition building in this context cannot be overstated. (For a brief overview of this context and the failure of the German workers’ parties, see Skinnell.) His instrumental language about the united front was meant to be a wake-up call to German workers’ parties. Building a united front was, or at very least needed to be, a tactical decision. In this context, Trotsky was adamant about a few points:

- Organizations must maintain their independence. He argued that the united front against fascism should “march separately, but strike together! Agree only on how to strike, whom to strike, and when to strike!”

- This united front had to be organized around specifics so that the dividing lines between organizations remained clear to the average worker. “No common platform…no common publications, banners, placards!”

- It should be composed of substantial groups of comparable size because it had to be able to deliver something. You did not enter a united front out of moral principle but as a tactical move to prevent catastrophe (German).

With this approach to coalition building, the immediate goal was not to create a shared subjectivity. The party itself focused on creating “class consciousness”—a shared subjectivity among workers. Creating a united front required little sense of respect for the leaders of the other organizations that you entered into the agreement with, or their politics. As Trotsky implored, “such an agreement can be concluded with the devil himself, with his grandmother.” Instead, the united front was meant to stop losses and build the social power of the oppressed against their oppressors.

In the aftermath of Trump’s presidency and the current onslaught of racist, anti-immigrant, anti-LGBTQ, sexist and anti-choice legislation sweeping the country, I would argue that the question of building coalitional subjectivity must connect with opposition to the “creeping shadow of fascism” and winning gains for oppressed people (Skinnell). With this perspective in mind, I reflect on my experiences in an organization that focused rather exclusively on opposition rather than coalitional subjectivity or winning gains.

Coalition Building in NWROC

When I learned about NWROC, it was during my first semester at the State University of New York at Albany (SUNY Albany) in August 1993. I didn’t know anyone on campus, and in my first weeks at the university, I was trying to connect with others. In 1993, the bulletin boards that proliferated campus were our “social media.” We used them to find out what concerts and events were going on around campus and in the city. While perusing one bulletin board, I stumbled across a poster for a meeting by a group called Youth Against Fascism (YAF). The poster headline read, “Smash the Fascists: All Out to Auburn, NY September 25!” It called on students to protest a group called the USA Nationalist Party who were holding a rally at Freedom Park in Auburn, New York on Saturday, September 25, 1993–Yom Kippur. Freedom Park is one of the city’s tributes to Underground Railroad leader and long-time Auburn resident Harriet Tubman. The YAF poster advertised an organizing meeting the following week, just days before the rally.

I attended the meeting—about 50 people convened in the Student Association Lounge in the university’s student union. During the meeting, I learned that YAF was a coalition of student and community groups from across New York state that formed in order to shut down the fascist rally. NWROC was part of that coalition, but it was unclear at that meeting who from YAF was also a member of NWROC. A dozen or so people at the meeting put forward YAF’s platform and organizing strategy, which began with their analysis of fascism. YAF organizers made various arguments about why people needed to fight fascism through direct action, some of these organizers cribbed their arguments from Leon Trotsky’s Fascism: What It Is, and How to Fight It, though I didn’t know it at the time. Some YAF organizers argued that fascism was endemic to capitalism, and they summarized the fascist platform as using the threat of downward mobility to scare white people into joining their ranks; fascists argued that it was “Jews from above; people of color from below; immigrants from abroad; and workers, feminists, and gay men and lesbians from within the white population who were destroying the country.” But as the YAF organizers argued, fascists lied to people because capitalism caused this downward mobility and pitted working class and poor people against one another. From these statements, it was clear to me that YAF was anti-capitalist.

YAF built their platform around the slogan “No free speech for fascists.” I questioned them about this stance: “Doesn’t that make you as bad as the fascists?” They responded by saying that they did not support the government creating a law to curtail free speech and that “speech is never free.” Any law created under the guise of curbing fascist organizing would be used against activists fighting fascism and racism, not against the fascists. Instead, YAF’s strategy relied on building a coalition of organizations who would call out their members to protest the KKK and neo-Nazis and shut down their attempts to rally in public.

Some YAF organizers took this argument a step further by saying that protestors should prevent fascist organizing “by any means necessary.” The discussion shifted, and I and other attendees questioned these speakers about their definition of militancy: what does “by any means necessary mean”? NWROC members argued that the crux of the discussion should be about self-defense. At the time, it was unclear to me which aspects of the discussion represented YAF’s politics and which aspects of the discussion represented NWROC’s politics, but I had some sense that there were different perspectives being advanced based on various points that people made.

In the latter part of the meeting, YAF organizers discussed plans for the counter- demonstration. The coalition organized several vans to shuttle people from Albany to Auburn early on the morning of the 25th, and the vans would return that night. Interested folks could attend for free but should bring food or money for food. Student groups across upstate New York who composed the YAF coalition arranged transportation from their universities, including SUNY Binghamton and Buffalo, Syracuse University, Cornell University, and several others.

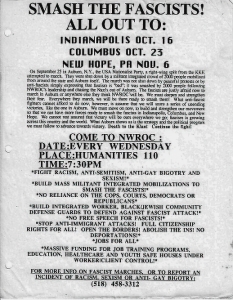

When the meeting concluded, I introduced myself to some YAF members. They asked if I was going to Auburn. I already had plans to visit my family in Binghamton that weekend. I told them that I would be at the next meeting, and I was. I saw NWROC posters around campus declaring victory in Auburn and calling people out to protest the KKK in Indianapolis, IN, a week after the Auburn rally. According to NWROC and others, 2000 counter-demonstrators showed up in Auburn and had chased the USA Nationalist Party members and sympathizers out of town (see fig.1) (Williams).

An example of a NWROC poster used to build anti-KKK/anti-Nazi work after the Auburn rally. This poster shows black ink on white paper. The heading at the top of the poster reads “SMASH THE FASCISTS! All OUT TO: Indianapolis Oct. 16, Columbus Oct. 23, New Hope, PA Nov. 6” (emphasis in original). The body of the poster presents NWROC’s take on the Auburn counterdemonstration: The USA Nationalist Party rally was “shut down by a militant integrated crowd of 2000 people mobilized from around the state and Auburn itself. The march was not shut down by peaceful protests or by anti-fascists simply expressing that fascism is ‘bad’; it was smashed by 2000 people following NWROC’s leadership and chasing the Nazi’s out of Auburn.”

After Auburn, the YAF coalition disintegrated. It was temporary, existing only to organize around the Auburn rally. However, NWROC continued their campaign to shut down KKK and neo-Nazi rallies throughout the northeast and Midwest “by any means necessary.” I learned that NWROC had local chapters in Detroit and Ann Arbor, MI as well as Albany, NY. The midwestern chapters played key roles in organizing future anti-Klan/anti-Nazi counterdemonstrations. I joined NWROC for the action in Indianapolis on 16 October 1993. It was an eye-opening experience that drew me into political organizing.

The KKK rally took place on the steps of the Indiana Statehouse. Estimates by a student reporter from Saint Mary’s College in Notre Dame, IN claim that 1000 people were present (Johnson, “Despite Police”). It seemed much larger to me. Officials had created a pen around the Statehouse steps leading into the building. About 100 feet from the steps, they erected a 10-foot-high chain-link fence. On the other side of this area, where you entered the lawn leading to the steps, the city had set up 4-foot-high plastic fencing. Between the fences, the KKK sympathizers and protestors intermingled. There were two or three entrances into this pen that were manned by cops dressed in riot gear. To enter the fenced-in area, you had to go through a metal detector located at one of these entrances. Next to the metal detectors were signs that said “No weapons. No glass bottles. No sticks.” While going through one of the metal detectors, cops made folks empty their pockets, open their bags, and get patted down. Once inside the pen, you could move wherever you liked. If you walked toward the Statehouse steps, you could see an endless row of police in riot gear lined up behind the fence. There were hundreds upon hundreds of cops, who were armed to the teeth. Helicopters flew overhead, but it wasn’t clear to me if they were with the cops or local news stations.

As the pen filled up, groups of KKK sympathizers and protestors fought. Cops roving through the pen carried plastic zip-tie style handcuffs. Occasionally, they arrested people for fighting and removed them from the pen. More commonly, the cops just let whatever happened happen. After some time, the KKK members took to the steps of the Statehouse. They arranged themselves in a line across the landing at the top of the steps. At the center, their leader stood at a microphone and spewed his BS (Johnson, “Despite Police”). Protestors tried to drown out his speech by chanting “Scum in sheets, get off our streets! Boys in blue you can go too!” or “No Nazi scum. No KKK. No racist, fascist USA.” Despite the chants, you could still hear the speaker because the KKK had a large sound system.

Fed up with the situation, some protestors attempted to rip down the chain-link fence leading to the Statehouse steps. When this happened, I was standing at the fence next to a Black man who had a small child sitting on his shoulders. They glared at the KKK members but did little else. The weight of the protestors clinging to the fence made it bow. Suddenly, the cops on the other side of the fence panicked. They paced down the line of the fence carrying huge jugs of pepper spray. They sprayed everyone on the other side of the fence. Just before I got sprayed in the face, I saw one cop raise his jug of pepper spray over his head to aim it at the child. I am not sure who, but people led me away from the scene at the fence toward the back of the pen. Tears poured from my eyes. Snot gushed from my nose. A reporter seized the moment to ask me about the experience. I launched into a tirade about how Indiana had spent countless dollars to provide a platform for the KKK who were there to recruit people to carry out a platform of racist terror. The night before the rally at the Statehouse the KKK had a cross burning in nearby Starke County (Johnson, “Despite Police”). I also ranted about how the cops were not interested in keeping the peace or they would not be pepper spraying young children and creating a ring for protestors and Klan sympathizers to duke it out. The discussions I had with YAF and NWROC members poured out of me.

By the time I regained my vision, the KKK members were leaving the Statehouse steps. Protestors rushed out the pen onto the streets around the Statehouse and toward one side of the building in an attempt to give the KKK some sort of sendoff as they left. At that point, hundreds of cops in riot gear and armed with large shields and nightsticks formed a phalanx in the street. They marched toward the protestors shouting orders to disperse and banging their shields. Most protestors did not move. Then, cops began shooting cans of tear gas at people. I saw one person get hit in the chest and a couple people pick up the cans and throw them back toward the police. It was chaos largely manufactured by the cops themselves. During this chaos, I heard windows of nearby buildings being smashed. At that point, I met up with other folks from NWROC, and we made our way back to our vehicles. My face was raw, and I was shaken. The experience galvanized my political work over the next period.

After the trip to Indianapolis, I began organizing with NWROC. It was the first time I had been involved in a political organization and the first time I had been immersed in a queer milieu. At the time, NWROC had a couple hundred members, but maybe half of those members were active. NWROC members were disproportionately queer and female [In writing about the counterdemonstration in Auburn, The Buffalo Times referred to the organization alternately as “Marxists lesbians” and a “lesbian rights group” (“Lesbian Rights Group”)]. It was also predominantly white, and most members ranged in age from 18 to 30. My involvement lasted from fall 1993 to spring 1995. This included traveling around the Midwest and northeast to participate in counterdemonstrations against the KKK and neo-Nazis in Columbus, OH, New Hope, PA, Coshocton, OH, and Hamtramck, MI, among others. To build for these demonstrations, I handed out leaflets and talked to students at SUNY Albany. I also participated in NWROC conferences and regional meetings in Albany, Detroit, and Ann Arbor.

On SUNY Albany campus, I helped build campaigns and carry out various actions that NWROC initiated, including a campaign to protest Binyamin Kahane, Meir Kahane’s son, who was slated to speak on campus in November 1993. In advertising the event, the student group that sponsored it, the Revisionist Zionist Alternative, used a quote from Meir Kahane arguing that Jewish people should “fight our enemies with knives, guns, and fists.” This list of enemies included Black Muslims, among others (“SUNY and Jewish Rights”). This campaign was one of many. I offer it only as an example. At times, it seemed like we were tabling or having informational pickets on campus daily. We also held internal meetings and study circles regularly, which meant that I spent very little time on schoolwork.

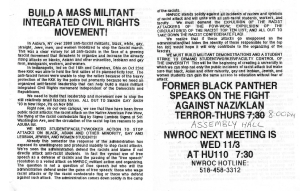

As my time in NWROC progressed, we put less and less resources into building coalitions on campus or with local organizations in the various places where we carried out work, and we devoted more and more resources to carrying out small actions on several different issues where the same dozen or so people participated. For example, in organizing action around Binyamin Kahane’s speaking engagement on campus, NWROC put out a call to protest the event without building an alliance with other campus organizations and individuals who expressed outrage over the speaker and advertising, such as the Albany State University Black Alliance, Rosa Clemente (Multicultural Affairs Director for the Student Government Association), or the International Socialist Organization—another leftist group on campus that was composed largely of graduate students. NWROC’s hyperactivism pushed many members and potential allies away and created a high barrier of entry for new ones. It also shifted the discourse within the organization. Discussions of tactics changed from building coalitions over specific issues to more amorphous talk of rebuilding a Civil Rights Movement (see fig. 2). Eventually, this talk of rebuilding a Civil Rights Movement transformed into talk about providing leadership to the people who showed up at the events that we participated in. First, we provided this “leadership” through our superior political analysis, and when few people responded to the political line in our speeches and leaflets, we provided this “leadership” through militant action on the scene, hoping to inspire others through our militancy.

An example of a NWROC leaflet used to build work against KKK/Nazi organizing and against racist provocations on the SUNY Albany campus, including the Kahane event. The leaflet uses black ink on white paper. The heading reads, “BUILD A MASS MILITANT INTEGRATED CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT!” The demands advanced in the leaflet culminate in the call for a “STUDENT STRIKE TO DEMAND STUDENT/WORKER/FACULTY CONTROL OF THE UNIVERSITY.” The leaflet ends, “FORMER BLACK PANTHER SPEAKS ON THE FIGHT AGAINST NAZI/KLAN TERROR—THURS 8:00 PM, ASSEMBLY HALL, NWROC NEXT MEETING IS WED 11/3 AT HU110 7:30, NWROC HOTLINE 518-458-3312” (emphasis in original).

Moving Forward

Looking back on these experiences and considering them in light of my previous discussion on how contemporary coalitions need to balance their work building a coalitional subjectivity with the struggles against oppression and the ability to win gains, NWROC’s approach to coalition building taught me a lot about what not to do. In parsing these lessons, I outline a few basic principles and a warning that guide my work:

- Coalition building requires that the basis for action be worked out together with other organizations who are interested in participating in it. It rarely works when one group advances a political line and expects others to sign on to a coalition after the fact.

- A coalition needs to be built around specific goals or demands and action plans. An approach to coalition building that shifts focus with every incident risks falling into hyperactivism where allies and members quickly burn out.

- Sustained coalitions often involve multiple goals or demands and action plans that can change over time. Such coalitions require that an infrastructure be developed with involvement from all coalition members or their elected representatives. Even so, there is a risk of losing members who disagree with the changes supported by the majority of the group. A healthy coalition should establish ways for members to express disagreement from the beginning, and these policies need to be respected and maintained throughout the life of the coalition.

- The coalition also risks losing members if the goals or demands are far beyond the group’s reach. For example, a small group that uses an informational picket against a racist speaker on a college campus risks failing miserably if the demands in their leaflets, speeches, and chants focus only on “student/worker/faculty control of the university” and excludes other demands that meet the needs of students, workers, and faculty members.

Over time, a coalition can cease to be a coalition and become a smaller group with a very high level of agreement. As numbers dwindle, this level of agreement increases. Once relationships with other organizations and the ability to attract new members wither, you’re left with a small group of people, and your actions amount to little more than a demonstration of your beliefs. Refusing to see this change, from a coalition to a home, of sorts, makes it difficult for the organizers to see that their goals, or the way that they implement them, have become a barrier rather than a bridge for new members and for creating change.

To move forward in this period, the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition might begin by parsing out which organizational goals speak to home building and which goals necessitate coalition building. Next steps might mean prioritizing issues around which to coalesce with others: there are plenty of injustices within our fields, institutions, and regions, which one(s) will the Coalition devote resources to and why? Finally, the Coalition will need to address whether these issues require building a new coalition and drawing other organizations into it or playing an active role in existing coalitions. Based on the scholarship detailing the Coalition’s development discussed previously, the Coalition is beginning to move beyond home building and expanding into coalition building (e.g., Graban, et al.). If we take that as a given, then the Coalition needs to be more deliberate about promoting relational literacy and to work toward promoting a sense of coalitional subjectivity by drawing the membership into discussions of next steps.

Works Cited

Bell, Sandra J., and Mary E. Delaney. “Collaborating across Difference: From Theory and Rhetoric to the Hard Reality of Building Coalitions.” Forging Radical Alliances Across Difference: Coalition Politics for the New Millennium. Eds. Jill M. Bystydzienski and Steven P. Schacht. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001. 63-76. Print.

Bizzell, Patricia, and K.J. Rawson. “Coalition of Who? Regendering Scholarly Community in the History of Rhetoric.” Peitho Journal vol. 18, no..1, 2015, 110-112. 25 Sept. 2023. </docs/peitho/files/2015/10/18.1BizzellRawson.pdf>.

Chávez, Karma R. “Counter-Public Enclaves and Understanding the Function of Rhetoric in Social Movement Coalition-Building.” Communication Quarterly vol. 59, no..1, 2011, 1-18.. 25 Sept. 2023. <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01463373.2010.541333>.

Chávez, Karma R. Queer Migration Politics: Activist Rhetoric and Coalitional Possibilities. Champaign, IL: U of Illinois Press, 2013.

Gaillet, Lynée L. “Growing Pains: Intergenerational Mentoring and Sustainability of the Coalition’s Mission.” Peitho Journal vol. 24, no. 2, 2022. 25 Sept. 2023. </article/growing-pains-intergenerational-mentoring-and-sustainability-of-the-coalitions-mission/>.

German, Lindsey. “The United Front: March Separately Strike Together.” Socialist Worker Review, vol. 69, 1984, 15-19. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. <https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/german/1984/10/unitedfront.html>.

Glenn, Cheryl, and Andrea A. Lunsford. “Coalition: A Meditation.” Peitho Journal, vol. 18, no. 1, 2015, 11-14. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. </docs/peitho/files/2015/10/18.1GlennLunsford.pdf>.

Gould, Deborah. “Becoming Coalitional: The Perverse Encounter of Queer to the Left and the Jesus People USA.” The Scholar and Feminist Online, vol. 14, no. 2, 2017. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. <https://sfonline.barnard.edu/becoming-coalitional-the-perverse-encounter-of-queer-to-the-left-and-the-jesus-people-usa/>.

Graban, Tarez Samra, Holly Hassel, and Kate Lisbeth Pantelides. “Feminists (in) Dialogue: Mapping Convergent Moments and Telling Divergent Histories of the CCCC Feminist Caucus and the CFSHRC.” Peitho Journal, vol. 24, no. 4, 2022. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. </article/ feminists-in-dialogue-mapping-convergent-moments-and-telling-divergent-histories-of-th e-cccc-feminist-caucus-and-the-cfshrc/>.

Johnson, Gavin P. “The Time is Always Now: A Conversation with Karma R. Chávez about Coalition and the Work to Come.” Spark: A 4C4Equality Journal, vol. 3, 2021. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. <https://sparkactivism.com/volume-3-call/conversation-with-karma-r-chavez/>.

Johnson, Kenya. “Despite Police, Protestors Persist in Indianapolis.” The Observer: The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s 18 Oct. 1993. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. <https://archives.nd.edu/Observer/v26/1993-10-18_v26_036.pdf>.

L’Eplattenier, Barbara E., and Lisa S. Mastrangelo. “The Evolution of Peitho.” Peitho Journal, vol. 24, no. 4, 2022. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. </article/the-evolution-of-peitho/>.

“Lesbian Rights Group Aims to Halt Supremacist March.” The Buffalo News 21 Sept. 1993. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. <https://buffalonews.com/news/lesbian-rights-group-aims-to-halt-supremacist-march/article_f0a696eb-d6f6-574c-ab05-a6df9a752681.html>.

Licona, Adela C., and Karma R. Chávez. “Relational Literacies and Their Coalitional Possibilities.” Peitho Journal, vol. 18, no. 1, 2015, 96-107. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. </docs/peitho/files/2015/10/18.1LiconaChavez.pdf>.

Pritha, Prasad. “‘Coalition Is Not a Home”: From Idealized Coalitions to Livable Lives.” Spark: A 4C4Equality Journal, vol. 3, 2021. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. <https://sparkactivism.com/volume-3-call/from-idealized-coalitions-to-livable-lives/>.

Reagon, Bernice J. “Coalition Politics: Turning the Century.” Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology. Ed. Barbara Smith. Latham, NY: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983. 358-368. Print.

“Resolutions 1922 On the Tactics of the Comintern.” Marxist Internet Archive, 2018. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. <https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/4th-congress/tactics-of-comintern.htm>.

Skinnell, Ryan. “Coalition-Building in the Creeping Shadow of Fascism.” Spark: A 4C4Equality Journal, vol. 3, 2021. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. < https://sparkactivism.com/volume-3-call/coalition-building-in-the-shadow-of-fascism/>.

“SUNY and Jewish Rights Groups Decry Militant Message.” The Chronicle of Higher Education 17 Nov. 1993. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. <https://www.chronicle.com/article/suny-and-jewish-groups -decry-militant-message/?cid=gen_sign_in>.

Trotsky, Leon. “For a Worker’s United Front Against Fascism.” Marxist Internet Archive, 1932. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. <https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/germany/1931/311208.htm>.

Williams, Scott W. “Harriet Ross Tubman (1819-1913): Timeline.” African American History of Western New York, nd. Web. 25 Sept. 2023. <http://www.math.buffalo.edu/~sww/0history/hwny-tubman.html>.

PDF

PDF