Addressing the Barriers between Us and that Future via Deep Rhetoricity

Addressing the Barriers between Us and that Future via Deep Rhetoricity

Peitho Volume 26 Issue 1, Fall 2023

Author(s): Romeo García, Gesa E Kirsch, Valeria Guevara Fernandez, and Nicole Salazar

Romeo García is Assistant Professor of Writing and Rhetoric Studies at the University of Utah. His interdisciplinary research on settler colonialism, coloniality, and decoloniality appears in College Composition and Communication, Rhetoric Society Quarterly, Across the Disciplines, and Rhetoric, Politics, and Culture. García is co-editor (with Damián Baca) of Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise, winner of the 2020 Conference on College Composition & Communication Outstanding Book Award (Edited Collection), and co-editor of both Unsettling Archival Research (with Gesa Kirsch, Caitlin Burns Allen, and Walker P. Smith, Southern Illinois University Press) and Pluriversal Literacies (with Ellen Cushman and Damián Baca, University of Pittsburgh Press).

Gesa E. Kirsch is Professor of Rhetoric and Composition at Soka University of America in Aliso Viejo, CA. Kirsch is author and editor of numerous books and articles, including Unsettling Archival Research, co-edited with Romeo García, Caitlin Burns Allen, and Walker Smith; Feminist Rhetorical Practices, co-authored with Jacqueline Jones Royster, winner of the Winifred Bruce Horner Outstanding Book Award; and More than Gold in California: The Life and Work of Dr. Mary Bennett Ritter, a critical edition of a 19th century memoir of a woman physician. She has served as Distinguished Visiting Professor at the University of Louisville and Syracuse University.

Valeria Guevara Fernandez is a third-year student at Soka University of America where she studies international relations. She is particularly interested in wealth management, investment opportunities in Latin America and Caribbean studies. Her Colombian family heritage and immigrant experience at age 7 inspired the research for this project. She is currently completing an internship with Vista Equity Partners and will be studying abroad in Puerto Rico where she will continue to expand her experience in the finance sector.

Nicole Salazar is a second-year student at Soka University of America majoring in Liberal Arts studies with a focus on Social Behavioral Sciences. She is most interested in the topics of psychology, specifically, forensic psychology. She is a member of Soka’s women’s soccer team. Her Mexican family roots and grandmother’s immigration story motivated the research described in this article.

Abstract: Abstract: So often left unquestioned within academia is how to be-and-think-with others beyond the axes of academic theories-values, unhinged from rhetorics of propriety, and unseated from automatic equations between a postion/ality and disposition. In our 2022 article, “Deep Rhetoricity as Methodological Grounds for Unsettling the Settled,” we introduced deep rhetoricity as an intervention into rhetorical practices of doing and as a praxis of invention within the same context. Our conversation was introductory, as we tentatively outlined and animated the inward epistemic principles of deep rhetoricity meant to unsettle the settled-ness of self, being, and doing: returns, careful reckonings, enduring tasks. In this companion piece centered on addressing the theme of barriers between us and that future, we open a conversation on the relational framework of being, doing, and thinking-with others within deep rhetoricity. Still in the exploratory stage, we tentatively outline and illustrate the outward epistemic principles of deep rhetoricity meant to unsettled the settled-ness of relationality: returns, careful reckonings, and being-with. The goal of this essay is to call for and work towards establishing a foundation to explore a relational framework of being-and-thinking-with others vis-à-vis deep rhetoricity. The essay features the hopes-struggles of rhetorical scholars and educators as well as illustrate the complexities, complicatedness, and missingness of doing human work and carrying out human projects-with others. Such friction amplifies the demand to learn how to be-and-think-with others otherwise.

Tags: careful reckonings, classroom, deep rhetoricity, storiesIn our CCC 2022 article, “Deep Rhetoricity as Methodological Grounds for Unsettling the Settled,” we (Gesa and Romeo) preliminarily sketched out deep rhetoricity. We acknowledged in that essay rhetoricity can convey a doing such as historiographic, archival, feminist rhetorical, and decolonial research, among other forms. At the onset, however, it was deliberated and determined that in the next iteration of conversations on doing what needed to be reemphasized was the unsettling of the settled. Our hope, as appealed by indigenous scholars such as Linda Tuhiwai Smith, was for an unsettling of self-being anchored by identity politics or benevolent lexicography; knowledge production organized by axes of academic theories-values inextricably linked to modern/colonial projects of territorial and epistemological expropriation; and politics of critical positioning detached from location and disengaged from the particularities and specificities in which power unfolds. Deep rhetoricity was our attempt to intervene in a doing undaunted by the hauntings, unscathed by the haunting situations, and unfazed by the wounded/ing spaces-places of a modern/colonial world system.[1] The actor-agent of this doing recognizes nobody exists outside of such and thus has it figure prominently in returns to spaces-places where one does and thinks.[2]

We advance a doing accountable and responsible to self(ves), others (broadly conceived), and communities. In the spirit of Gayatri Spivak, we set out to think of a doing not purely academic, situated squarely as a responsibility to what is formalizable (e.g., responding – being answerable to a call to action), what must endure (e.g., the ungraspable), and to the trace of the other (radical contamination). Such a doing underscores an ethos unhinged from an allegiance to a proper name or finality and grounded instead in being present to self(ves), others (nonliving, nonhuman), and the infinite demand for getting caught up. In the vein of Donna Haraway and Linda Alcoff’s work on epistemology, situated knowledge, and truth, we also conceived of a doing unseated from automatic equations between a postion/ality and disposition. Herein lies its formation as praxis insofar that it is a doing grounded in becoming ready to be answerable for how one has come to walk and see the world and interact and exchange meaning with others. Deep rhetoricity was our wager all doing demands as a starting point the corporeal exercise of addressing oneself to hauntings, inheritances, and dwellings as obligation-responsibility. The actor-agent of this doing would embody an ethos and praxis of unsettling the settled.

Deep rhetoricity is our attempt to situate ethos and praxis in the elsewhere and otherwise. Alcoff argues we need to relearn how to make truth claims and reconstruct epistemology. That is a course-of-action, however im/possible, we accept, and one that demands the language of constellations and coalitions. A truth: our stories-so-far are a cosmo of constellated hauntings, inheritances, and dwellings. The racist Arthur de Gobineau understood the world was being staged for a haunting-and-ghostly totality to become a structure of feeling: “so long as even their shadows remain [e.g., monuments], the building[s] stands [e.g., economic, authorial, educational, political, and knowledge], the body seems to have a soul, the pale ghost walks” (33). Though not all feel equally the haunt in their bones, we argue in our essay, we are all in this palimpsest narrative—Raymond Williams’ structures of feeling or Michael Taussig’s public secret—of settler sites, haunted/ing communities, and wounded/ing spaces-places. It will take a coalition to unstage such a totality. In the spirit of Karen Barad, Walter Mignolo and Catherine Walsh, and others then, deep rhetoricity is about the staging of an epistemic doing that fractures barriers between us (living, nonliving, nonhuman) to make visible invisible structures of feeling that attune us. [3] The actor-agent of this doing is driven by an ethic of being-and-thinking-with others otherwise that underscores critical frameworks of feminist rhetorical practices and coalition-building. This doing is animated and facilitated though by the epistemic principles of returns, careful reckonings, and enduring tasks to ensure a responsibility beyond mere representation.

The focus of our previous essay is on the inward process of deep rhetoricity. By couching ethos and praxis in hauntings, inheritances, and dwelling as language, rhetoric, and corporeal exercises of address we are afforded the opportunity to deliberate an-other set of choices, options, and responsibilities. We concur with scholars such as Jacques Derrida, Avery Gordon, Sylvia Wynters, and others that an-other epistemological framework for the living is needed; one predicated on an ontology of truth not instituted by an epistemology that dehumanizes and devalues human beings (coloniality of knowledge) but one that strives to liberate, however im/possible, pluriversal truths and constellated truths; one that partakes in responsible and accountable knowledge production instead of idealized reconstructions of knowledge; one that underscores a humanness in the service of others, a being human as praxes. What continues to be at stake in our inability to live or have something in-common is the possibilities of new stories. The actor-agent of this doing foregoes the given-ness and peels back the layers of what is constituted as settled. To begin every conversation on doing with hauntings, inheritances, and dwellings is to station self-being within that intermediary stage between what is formalizable and what must endure as an ongoing task. This is the very space-place of deep rhetoricity. [4]

We acknowledge that deep rhetoricity can be aligned with the Modernity/Coloniality Collective’s prospective task and feminist and coalitional work. A return to hauntings, inheritances, and dwellings is a return to where one does and thinks; a careful reckoning with the settled-ness of self-being is a learning how to unlearn cultural and thinking programs to relearn how to be-and-think-with self(ves), others, and communities otherwise; and the enduring task of getting caught up is a commitment to hope-struggle. But because the impetus for deep rhetoricity was to go beyond mere critique of Western epistemology and advance a doing attuned to the messiness of life, agency, and coalitional work, we did not advance it as a decolonial project.[5] For anything with a proper name, and the irony is not lost on us here, prescribes a proper method of seeing, being, and doing.[6] The same goes with feminist-coalition work and the advancement of a certain form of agency. Deep rhetoricity emerges in the vein of Saba Mahmood and Kenna Neitch, where agency is not a synonym for resistance, subversion, and/or resignification of hegemonic norms but rather reflective of a capacity for action that haunting(s)-situation(s) enable and create. It neither portends to be a panacea nor a mechanized application of a proper method but rather a commitment to/wards unsettling the settled. The actor-agent of this doing engages reconstructive work in epistemology to surrender formal representations of proper names, producing a rupture, creating a clearing, and initiating an opening. This must remain most vital within feminist rhetorical practices and coalitional work where the door must remain open to anyone, wherever they may be (Fanon) and in the non-name of all (Acosta).

The reconstruction of epistemology that we forward in this essay is based on the outward-facing aspects of deep rhetoricity. Its epistemic principles-as-heuristics are not a panacea but build on that hope for a future of mutual wor(l)ding animated by a struggle to unsettle “the barriers between us” (Lorde 57). Like our previous essay, our goal is to open up a conversation, this time on being-and-thinking-with others otherwise. The relational framework we advance in this essay is informed by feminist and coalitional work as well as scholars such as Audre Lorde, Jim Corder, Joy, Ritchie, Frantz Fanon, María Lugones, bell hooks, Jacqueline Jones Royster, Andrea Riley Mukavetz, and Ana Ribero and Sonia Arellano. We tentatively outline three epistemic principles that are introductory and subject to revision. They are not carried out evenly in this essay but figure prominently throughout. The principles are as follows:

- Returns to our ways of walking and seeing the world.

- Careful reckonings with our understandings of being-and-thinking-with and exchanging meaning with others.

- Being-with, or a commitment of being-and-thinking-with others (past-present-future; environment; living, nonliving, nonhuman) otherwise.

Though incomplete, we believe the above epistemic principles are points-of-references that can put feminist rhetorical practices and coalition-building on pathways towards the possibilities of new stories amid troubling times and pedagogical challenges. In this context, deep rhetoricity will remain quite ambitious in what it strives for, intervention through the unsettling of the settled and (re/co)-invention for the sake of relearning how to see and walk the world and interact and exchange meaning with others otherwise. [7] The modification to rhetoricity here is less about achieving rhetorical effect and more about making visible the work of doing before us all. Such doing will echo the undertones of love, care, healing, and learning that are so important to and within frameworks of feminist rhetorical practices and coalition-building work.

Feminist coalition-building, as we envision it, is rooted in principles articulated and advocated by feminist scholars and activists over several decades. While it is beyond the scope of this essay to discuss those principles in detail, we list a number of them below to situate our work and to acknowledge the important work and legacies of feminist activist scholars, scholars who have charted multiple paths for us; have insisted on making commitments to community, collaboration, and coalition-building; and have created/ claimed spaces for women (and women-identified people) whose voices and perspectives that have long been missing, ignored, silenced, or erased from public memory (Applegarth, Buchanan & Ryan, Enoch, Glenn, Logan, Ratcliffe, Royster). Among the feminist activist principles that ground our work are the following:

- questioning the status quo of gendered, hetero-normative, social, political, cultural, economic systems that privilege small groups of people while disempowering/alienating a large number of others, whose stories, lived experiences, and communities have been deemed unimportant, marginal, or deliberately omitted from public narratives (Butler; Duplessis and Snitow; Hanish; Rich).

- questioning epistemological/ontological assumptions of research methods and methodologies and the ethos/ethical practices of researchers. While it is now commonplace among rhetoric and writing studies scholars to reflect on their membership in and commitment to the communities they are studying, early feminist scholars and activists were the ones who insisted on and argued for the importance of these principles (Bizzell, Gilligan, Jagger, Harding, hooks, Lorde, Spivak, Royster, Smith, Sandoval).

- reflecting on one’s own ethos as scholars, teachers, community members, and activists (Ryan, Myers and Jones) while working toward reciprocity and collaboration among researchers and community members (Alcoff; Chilisa; Cushman; Powell and Takayoshi; Riley-Mukavetz). That means scholars engage in shared knowledge-building, work with community members who set priorities for the research agenda and for best use of (re)sources–in contrast to Western research practices steeped in traditions of gathering/extracting/exploiting information from community members that can–and have–caused great harm (Caswell; Hughes-Watkins; McCracken and Hogan; Cushman). Reciprocity and collaboration involve listening to community members and centering their needs, values, and perspectives rather than imposing the researchers’ agenda, questions, and values on the community. It also involves protecting the dignity, respect, and autonomy of those we study with an emphasis on fair, ethical, dignified portrayals of research participants and building communities of solidarity.

- developing new tools, frameworks, and methodologies for conducting research, such as the analytical frameworks articulated by Royster and Kirsch (critical imagination, strategic contemplation, social circulation, and globalization/ transnationalism). It entails efforts to disrupt/unsettle supposedly “neutral /objective points of view” which tend to reflect white western male perspectives. Moreover, it comes with efforts to narrate a greater variety of stories and more complex, diverse representation of human experiences (Graban, Gutenson and Robinson, McDuffie and Ames, Logan, Royster, Schell, VanHaitsma).

- working toward a sense of care, well-being, and love towards those we work with (Corder, hooks, Lorde). Feminist scholars have long recognized that relationships of care can and do create unequal power relations, yet rather than avoiding those inequalities, feminist scholars and activists have challenged researchers to acknowledge potential power differentials and apply an ethics of care to support those who might find themselves in vulnerable positions (Gilligan, Noddings, Tronto).

Embracing deep rhetoricity as an intervention into the settled can be helpful to feminist activist and coalitional principles. First, because an ethos and praxis of unsettling the settled remains oriented to power structures and hierarchies based in Western settler colonialism, coloniality, patriarchy, and capitalism. Second, because the epistemic principles of deep rhetoricity as heuristics underscore deliberative intentions to produce ruptures, create clearings, and initiate openings. Joy Ritchie warned experiences are not universal, strategic essentialism is only a temporary point of departure, and self-analysis and reflexivity are vital to collective work. Uninterested in hand-waving or “virtue signaling,” we advance a doing that incessantly grounds a question, where are the lessons of ethos and praxis being proposed from? If we are where we do and think then hauntings, inheritances, and dwellings must figure prominently in doings. And third, because embracing deep rhetoricity is about standing at the nexus of an-other’s stories-so-far and possibilities of new stories as an ethic of love, care, healing, and learning.

The goal of this essay is to animate each facet of the outward-facing aspects of deep rhetoricity some of which occurs within the classrooms in which we teach. Our essay below is organized into two sections. In the first section, we explore the barriers between us and a future otherwise; the hope-struggle that underscore both possibilities as well as the complexities, complicatedness, and messiness of doing human work and carrying out human projects. Such reflections are necessary because sometimes theory and theoretically informed praxis do not easily translate or bode well in practice. This section includes case studies drawn from Kirsch and García’s research and teaching at two different institutions. The second section offers a reflection by all four co-authors, guided by two questions: one, what does feminist coalition-building mean? And two, what does feminist coalition building look like? Such a reflection is necessary given an essay that aims to illustrate how feminist coalition-building might work among a group of four co-authors with diverse backgrounds, lived experiences, and academic standing/privilege.

The Barriers Between Us and that Future

The discussion that follows draws on examples from undergraduate and graduate courses that Kirsch and García teach. We share examples of how we resist palimpsest narratives that aim to normalize haunted/ing structures of feeling (Williams; Gordon), smooth frictions (Lueck and Nasr), hide fissures (Mignolo), and keep the dark corners (and secrets) of history out of sight and out of mind (Bunch). The discussion aims to animate our attempts at implementing the outward epistemic principles of deep rhetoricity amid troubling times and pedagogical challenges.

Kirsch reflects on one question that animates this essay: How can we learn to practice being-and-thinking-with others otherwise in and out of the classroom? Drawing on an undergraduate course, “Writing the Archives,” Kirsch offers a discussion of her feminist commitments and coalition-building practices by working with two student authors, Valeria Guevara Fernandez and Nicole Salazar, who reflect on their own experiences of working with primary sources, conducting archival research, and engaging in feminist coalition-building and activism. Rather than speaking for or about students, Kirsch decided to invite students to be-with/in this essay as coauthors, sharing their insights, reflections, and challenges of unsettling settled histories. Kirsch imagines and enacts a pedagogy that invites pathways of learning to unlearn as being-with, highlighting the possibilities of the outward-facing principles of deep rhetoricity and the opportunities that can arise when we find a productive tension between intervention, our current sets of stories-so-far, and invention, the possibilities of new stories.

García reflects on a recent experience in Tokyo and then segues by recalling work he does with students at the University of Utah (UoU). He then contends with a coloniality of instruction-and-curriculum (broadly conceived) in Utah. García proceeds by making an argument for the utility of settler archival research as place-based pedagogy that invites students to return to and carefully reckon with how their stories-so-far and everyday adhere to, interact with, and carry out the histories, cultural memories, and literacy-rhetorical practices settler archives represent. He reflects on failures and minimal successes in an undergraduate course, “Intermediate Writing,” that marks the interplay between a hope for wor(l)ding a future otherwise and the struggle to unsettle “the barriers between us and that future” (Lorde 57) through the human work-projects of unsettling the settled, being-and-thinking-with, and mutual deliberation-determination of an-other set of choices, options, and responsibilities.

Standing at the Nexus of Stories-so-far and the Possibilities-of-New-Stories

In this section, I [Gesa] explore the outward-facing epistemic principles of deep rhetoricity against the backdrop of pedagogical challenges and opportunities. In many ways, deep rhetoricity resonates with the challenge posed by Audre Lorde:

… looking out and beyond to the future we are creating, [recognizing that] we are part of communities that interact, … and arm[ing] ourselves with accurate perceptions of the barriers between us and that future” (57).

Lorde’s call anchors the three inward epistemic principles of deep rhetoricity as an ethos and praxis of returns to our local histories of hauntings, inheritances, and dwellings; careful reckonings with self as the place of multiple returns and becomings; and enduring tasks of this work. What prompts me to continue exploring deep rhetoricity is the potential of the outward journey: the epistemic principle of standing at the nexus of another’s set of stories-so-far and possibilities of new stories.

When we envision “standing at the nexus” of these two spaces, we invoke movement, fluidity, change–all enduring tasks. Drawing inspiration from Lorde and from hooks, who reminds us that “solidarity requires sustained, outgoing commitment,” I invite students, in an upper division course on “Writing the Archives” to explore what it means to unsettle settled histories, to confront hauntings and inheritances, and to establish an ethos and praxis that address the barriers between us and another future via a praxis of being-with others, otherwise. In the course, we study–and contribute to–many different kinds of archives, including personal and family archives, community archives, digital archives, ephemeral archives, and archives-in-the-making. In the syllabus, I describe the course goals as follows:

This seminar explores archives as sites of cultural interpretation, civic engagement, and social change. We will explore a broad range of archives, including family archives, community archives, digital archives, and institutional archives. Drawing on feminist, rhetorical, indigenous, decolonial, and other perspectives, we will focus on what stories, social memories, and public histories can emerge from archival research, and just as important, what remains hidden, missing, silenced, or erased in archival collections. We will also study how archives in your concentration can illuminate the histories, intellectual frameworks, and methodologies of your field of study.

The course readings are interdisciplinary and include work by feminist and feminist rhetorical scholars, Indigenous scholars, and African American scholars, amongst others. We read chapters from Unsettling Archival Research (Kirsch, García, Allen and Smith), articles from a special issue of the digital journal Across the Disciplines with the theme Unsettling the Archives, and articles by critical archival scholars. One of the articles that became a powerful touchstone in class was Michelle Caswell’s “Seeing Yourself in History: Community Archives and the Fight Against Symbolic Annihilation.” Caswell explains that she adapted the term symbolic annihilation from “feminist media scholars in the 1970s” who use it to “describe what happens to members of marginalized groups when they are absent, grossly under-represented, maligned, or trivialized…” (27). Caswell deliberately calls out the willful erasure, disremembering, and omission of records that are part and parcel of many institutional “capital-A” archives, archives that represent on a limited version of history: that of the powerful, wealthy, often white-identified men. She cautions:

“If archives are to be true and meaningful reflections of the diversity of society instead of distorted funhouse mirrors that magnify privilege, then they must dispense with antiquated notions of whose history counts and make deliberate efforts to collect voices that have been marginalized by the mainstream” (p. 36).

In class discussion the term “symbolic annihilation” resonated as both a powerful and haunting concept, offering students an entry point, a measure, a criterion for assessing what happens when “stories-so-far” are missing entirely from public discourse/memory and thereby negate the “possibilities of new stories.”

The first half of the semester we focused on readings and case studies that illustrate how researchers can engage in reciprocal work, contribute to the communities they are studying, and produce narratives that unsettle settled histories. Students undertake three assignments: an “archival adventure,” a low-stakes exploratory assignment that invites discovery of personal or family archives and reflection on what constitutes an archive, how collections are created, and how memory/ meaning are attached to artifacts. The second assignment explores the conventions of a research proposal and asks students to articulate an original research project that draws on primary sources housed in a digital archive and/or one that builds on the archival adventure. The third assignment asks students to conduct the research they proposed in the second assignment. That is, students follow through on the research goals they set, including analyzing and interpreting primary sources from digital archives, and/or creating original sources via conducting interviews/collecting materials, and/or examining artifacts in small-a archives.

In all three assignments I invite students to see themselves as researchers who reflect on stories-so-far and, in the process, work toward the possibilities of new stories that might evolve, challenge, or amend stories-so-far. I ask students to practice reciprocity, a being-and-thinking-with, to make a contribution to the community(ies) they study and/or the archives they work with, so that the archival research they are conducting can enable the possibilities of new stories. One of the evaluation criteria for the final assignment, the original research project, addresses outcome, impact, and contribution.

The writer clearly explains how conclusions are drawn, what contributions the research makes, and considers the impact of the research, including likely impact on intended audiences. The writer considers potential reciprocity, benefits, harms to participants/ community. Explains how the results will be disseminated and why these means are appropriate to the subject matter and audience.

Finally, I invite students to articulate the contribution(s) they might be able to make to the communities they are studying. In many ways, this assignment sequence aligns with García’s portfolio requirements: constituted by returns home (archival adventure), careful reckonings with stories-so-far (research proposal) and a commitment to reciprocity, to being-and-thinking-with others, otherwise (original research project).

In the hyperlinks below, readers encounter the words and work of Valeria Guevara Fernandez and Nicole Salazar who describe and reflect on their archival research projects and what that work means to them. Guevara Fernandez’s research project touches on the many ways in which archival materials can get flattened, homogenized, erased; her research focused on holdings in the University of Louisville (UofL) Oral History Center. What caught her attention were nine oral histories–testimonios actually (more on this below)–all classified with a single, generic description: “Latin Americans – United States.” As she was about to embark on her research, Guevara Fernandez reflects:

“As I was browsing through the long list of subjects, a specific one caught my attention: “Latin Americans – United States”. The lack of detail in its title is what drew me in the most. Was this an archive about immigration? Politics? Xenophobia?”

As Guevara Fernandez quickly discovered, issues of access, selection, power, and privilege are deeply intertwined with archival holdings. She deliberately positioned herself at the nexus of stories-so-far and the possibilities of new stories by making a critical intervention: engaging in archival labor. She contacted Heather Fox, the director of the UofL Oral History Center and started a fruitful collaboration, taking on the role of “activist archivist” (Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge) and serving as a vital contributor to the archives by creating new records, coding interviews in both Spanish and English, analyzing themes, and making visible the lost and hidden histories contained in these testimonios. Quite literally, Guevara Fernandez began creating presence from absence and sounds from silence with her research project.

For Nicole Salazar, connections of stories-so-far and the possibilities-of-new-stories were invoked when she began her archival adventure by sorting through bins of her grandmother’s clothing, many of which were sewn by her grandmother, an accomplished seamstress who worked in factories that produced designer fashion.

“My grandma worked many jobs as she was raising my mom and my aunts. All her jobs always had something to do with sewing, whether it be swimsuits when she worked at La Sirena, costumes while she worked at a factory called Clemente, or luxury purses and belts at the Louis Vuitton factory not too far from her house.”

As Nicole sorted through the bins, she came upon a pair of well-worn, low-rise jeans, an item of clothing that she learns tells the story of intergenerational, border-crossing connections. Here, we see Nicole “bearing and being a witness to stories-so-far and embracing the possibilities of new stories that she is able to embody, a college student and athlete.” Nicole reflects:

“The majority were memories of my mom since the clothes used to be hers with an occasional piece or two of my Nina’s but when I showed her a pair of light washed low-rise Levi’s, my grandma had lots to share… The low-rise Levi’s were hers when she was in her early 20s and later on she passed them down to my mom. To think that this pair of denim was over twice my age and had seen more of the world than I had was mind blowing. I was so excited to think that a pair of jeans that were once my grandma’s and then my mom’s could be mine, and that I could make my own memories with them. Once we finished running through the other items I selected, I rushed to try on my new pairs of jeans. I put them on and I immediately felt a sense of belonging. Not only because they fit like a glove, but also because I felt like I filled in the missing part of a puzzle. I had the opportunity to carry on the lineage of the Levi’s that had been well loved by my family before me; it felt like an honor to wear them.”

Nicole’s discovery of her grandmother’s sewing skills and sense of fashion led Nicole to a research project focused on a community where fashion and style are used as elements of activism: the community of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. Through exploring an archive in the making, that of the Los Angeles house of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, and conducting interviews with current sisters, Nicole was able to reckon with stories-so-far, build solidarity across communities, and learn to be with/think with others, otherwise.

Creating Coalitions of Solidarity via Testimonios

Creating Coalitions of Solidarity via Fashion Choices

An Experience of the Im/Possible

Recently, I (Romeo) was in Japan with the family. We visited TeamLab Planets (Tokyo), an art installation that aims to unsettle barriers between self and boundaries, self and artwork, and self and others. Its theme, “Together with Others, Immerse your Entire Body, Perceive with your Body, and Become One with the World,” is aspirational, an invitation to learn how to be-and-think-with others otherwise—an archival impression. Activities peeled back layers of accessories (quasi bare-life), unsettled the grounds on which we walk (obscuring the senses), and simulated journeys from darkness to light (regeneration of life). [8] Feminist and coalitional principles were unavoidable. And a decolonial ethic, ethos, and praxis of learning-unlearning-relearning was not lost on me.[9] But the full-body immersive experience, for which I will call a decolonizing archival impression, was actually more emblematic of more to the inward and outward facing aspects of deep rhetoricity. Deep rhetoricity, conceives of our stories-so-far as archives, its epistemic principles the vehicle in which to engage in a slow and deep (de) and (re)-compositioning of self. Returns and careful reckonings reposition the contents of our archives so that we can reposition ourselves in relation to it otherwise while enduring tasks invite the ongoing process of initiating archival impressions otherwise.

Returns. The first installation, “Waterfall of Light Particles at the Top of an Incline,” invites participants to enter a space of darkness and water. Both are intended to unsettle the grounds by which one walks and sees; one is but walking into the abyss of darkness amongst other shadows. It was not lost on me either the significance of entering spaces-places as stories-so-far and the symbolism of water both in its ability to restore self(ves) and invite a re-connection with [We/arth]—we are all in and part of an archive. The second installation, “Soft Black Hole–Your Body becomes a Space that Influences another Body,” invites participants into an ever-changing space. The beanbags succumb to the weight of others and in turn affects the bodies of others; an archive and its archival impressions. It is meant to underscore how we always already stand at the nexus of an-other’s stories-so-far and the possibilities of new stories. How then, I wondered, do we become more intentional with the way we initiate such impressions?

Careful reckonings. Perhaps the most moving installations was “Floating in the Falling Universe of Flowers.” We laid down amongst other shadows and playfully world-traveled (Lugones) into the universe of the seasonal bloom, change, and de-composition (diastema). Individuality ceased to be, shadows coalesced, and in a moment in time the space was but the substance of humanity and air the song of [We/arth-ly] particles being-and-thinking-with others—archival impressions constellating an archive. The decentralization of self and other meant we were once again distributed of the same root and that all bodies (living, nonliving, nonhuman) were one heart reflecting its surroundings; [We] were all just Matter. It was in this moment that I came to realize that the story of life before us all was not that of the [I] or the [You] but of the [We/arth]. And in that story, being-and-thinking-with others no longer meant finding the proper words or identifying a proper way but rather what [We] hoped would live-on (sur-vie) in the wor(l)lding of a future of the [We/arth] after our own de-composition; a Matter otherwise.[10]

Enduring tasks. Every installation immersed the senses in a way to illustrate the effects of presence and consequences of that presence. They amplified the ability for non-humans to (re)attune and of non-humans to alter the ambience. “The tragedy” of a human being, Fanon (echoing Neitzsche) would tell us, “is that [we were] once a child” (231). Yet, in the art installation I was like Chihiro in Spirited Away who could see, feel, and hear the wind of the [Earth] pull, once again; because all the years were inside of me. For a moment, I was a child again–before the interruption that unsettled my childhood–and existed within a cosmo of fleeting glimpses, borderless worlds, and endless possibilities beyond myself. Life, agency, and rhetoric shifted in register to shared values: where will we choose to stand in order to see, welcome, know, be present to, and be a witness to an-other? what will we have wanted from one another after we tell our stories-so-far? But then came the interruption that ended the exhibit and the question of whether I or a generous reciprocity will ever have arrived somewhere, someday?[11] The enduring task for me was (re)learning how to reconnect with a doing that I once knew.

The exhibit was about stories-so-far and the possibilities of new stories. That is a feminist aspiration. Deep rhetoricity can help facilitate its principles in nuanced ways though by ensuring returns, careful reckonings, and enduring tasks remain at the fore. The exhibit was about hope-struggle. That is a coalitional longing. Deep rhetoricity can advance its principles in nuanced ways though with an ethic of being-and-thinking-with which assures in the words of indigenous and native feminist scholars such as Maile Arvin, Eve Tuck, and Angie Morrill that longing remains “people-possessed” rather than “individually self-possessed” (25). I thought to myself after the experience, “if an art installation that is a byproduct of human doings could create such dispossessions in me there is no reason to believe such im/possibilities are subject to a specific time frame in life.” Sandra Cisneros’ poem, “Eleven,” speaks to this: “all the years inside of me–ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two and one” (n.p.). I am both an archive, “repositories of feeling and emotions” (Cvetkovich (7), and an “archive in the making” (Browne 51). Perhaps, the tragedy of being human is forgetting we are self(ves), stories that are not fixed but always subject to change due in part to the initiating of archival impressions—that which acts on one’s archive rhetorically. My experience with TeamLab is what I strive for at the UofU amongst the undergraduate students I work with, which I have written about elsewhere (García and Hinojosa).

Coloniality of Instruction-and-Curriculum

Utahans and Utah stand apart. I say this at the risk of homogenizing culture and reducing rhetorics of place to a monolith.[12] In Utah, K-12 education, religion, and group circles are a prism by which to see coloniality of instruction-and-curriculum, inseparable from coloniality of knowledge–the invisible constitutive side (and not derivative)–and being. Especially if by power we in part mean epistemic and aesthetic campaigns to hoard and produce knowledge in excess that feed a war to dominate information (and mediums of circulation) fought on the battlefields of ideas (Man), images (Human), and ends (Rights-to). It was during my first year at the UofU, and from both students’ strong sense of obligation-responsibility to and my own readings of church-settler discourse on work,[13] that I encountered the work of reestablishing Zion and instructing salvation, reeducation, conversion, and restoration (work-instruction). This, in addition to my readings of discourse by Spanish Friars and Jesuits, Kant, and Hegel of whom emphasized instruction, curriculum, and/or pedagogy,[14] would lead me to coloniality of instruction-and-curriculum. [15] In Utah, it unfolds as the idea of Mormon/ism,[16] land as inheritance, an Other-as-Same relation, and work-instruction, all of which produce images of empty landscapes from which the inhabiting bodies of the other vanish or disappear. These are all archival impressions that feed into a much larger modern/colonial and settlerizing archive.

In part, without the classroom of education (broadly conceived) and coloniality of instruction-and-curriculum, neither coloniality as a disputed logic of domination, management, and control nor the epistemological regime of modernity could have been consolidated and sustained so successfully across space-place and time. [17] Coloniality of instruction-and-curriculum is the medium in which knowledge becomes factual and the tool by which epistemic obedience is managed and controlled. It is a settler-centered instruction in which educators, like the “men of letters” of the past, are entangled in informing-giving form to coloniality of knowledge. They become complicit in naturalizing a colonial matrix of power and its modus operandi of modernity/coloniality–“The control of labor and subjectivity, the practices and policies of genocide and enslavement, the pillage of life and land, and the denials and destruction of knowledge, humanity, spirituality, and cosmo-existence” (Mignolo and Walsh 16)–cloaked by images of empty landscapes, narratives of land waiting to be discovered, owned, and transformed into fertile “resources,” and rhetorics of peaceful Man-Human possessing the masculinity and intelligence to transform land into fertile “resources.” For me, students’ stories-so-far that year were examples of what coloniality of instruction-and-curriculum has done to and made of them. Because stories are imbued with meaning and consequences insofar that they circulate widely, have structural underpinnings, and carry material consequences (Rohrer 189). Students that year were a testament that stories are political because they “mobilize” histories and geographies of power (Alexander and Mohanty 31). But that too is a story-so-far.

Neither Utah nor the students I teach are inherent or essential to themselves. Coloniality of instruction-and-curriculum in Utah thus can be approached a racial matrix that peddles racist worldviews predicated on the pretext of epistemic and ontological difference; law of who can be in-common; and subtext for coloniality of power. It affords us a window, in other words, into discourse-about actions (Benoit 70; 75). Coloniality of instruction-and-curriculum plays a role, adjacent to the material forms of public memory and everyday human projects in Utah, in how the past and certain ghosts are kept alive in ways that rewrites Utah in modern/colonial ways. But again, that is but a story-so-far. This means that if space-place, language, and identity are made by the same token they can be remade. This experience allowed me to coalesce the interworking’s of deep rhetoricity, decolonial work, and feminist coalition-building. And what resulted my first year at the UofU was an archival approach, an effort to create a public record that would afford students the opportunity to view the contents of their archives as stories-so-far and initiate decolonizing archival impressions; the unsettling of the settled-ness of Self.

The Fly in the Elephant’s Nose

My first year at the UofU was marked by racist fliers, not-in-Utahism, determined epistemic ignorance, and Utahn niceness-politeness. But to identify students as problems is in itself problematic. Corder claims we are all narratives of histories, dogmas, and arguments. Sometimes they crush up against each other (19). So, when students carried out rhetorics of epistemology through church-settler epideictic rhetoric–“they [the other] love when we bring them things [the gift]”–during the first week of my “Intermediate Writing” course I choose to see this as an opportunity. If coloniality of instruction-and-curriculum has informed how such students walk and see the world and interact and exchange meaning with others by the same token both can be the means to unsettle barriers between us and bring forth a future of being-and-thinking-with each other otherwise. Friction, in the vein of Anna Tsing, became part of my vocabulary and pedagogical praxis. It afforded one way to think about what happens when there is an opportunity for non-humans (people, stories, knowledge) to come together and get to work. Things, however, do not always go as planned, and sometimes friction is just resistance.

If the rhetoric of place and the everyday are outcomes of literacies, rhetorics, and human projects by the same token they can be the means for a new arrangement. That kind of human work, however, requires a public record, cultural (archives) and individual (self as stories-so-far). The racist fliers found on campus were part of it. And so, we began there. A public record can afford students opportunities to utilize hauntings, inheritances, and dwellings as categories of analysis that can point towards connections between the past and the present in terms of social activities. In Utah, those activities can be as small as partaking in a service mission and as large as views on race and sexual orientation shared by the Church. A turning point for me in the ways I teach about settler colonialism and coloniality came by way of an email from a student. They were bothered by their peers and appealed for “more accurate accounts” of Utah history. The student offered to “assist” me in “researching and planning” and therein emerged my archival research of church-settlers of Utah. The student introduced me to the Book of Mormon and the General Conference corpus which led me down a rabbit hole and to the Journal of Discourses and The Millennial Star (and Ensign).

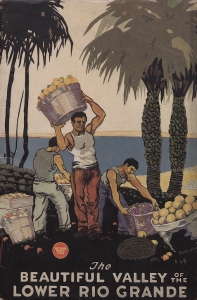

Now, students were not inclined to accept conversations about settler colonialism or coloniality much less if they were abstract. So, I turned inward to the haunting(s)-situation(s) I know while I acquainted myself with church-settler history in Utah. In my previous work with students at the University of Texas-Rio Grande Valley I had done archival research on settler-pioneers of the LRGV (see image below). This activity set in motion my endeavor to be vulnerable and be-and-think-with others, unsettling the distance and barriers between us. It animated Avery Gordon’s argument about how [We] are all part of and in this story. My hope was that settler archives would illustrate how ideas “dwell across the ages in the concepts and institutions human beings have built” (L. Gordon 13). Concept and institutions are what allow ideas to appear and become consequential within and beyond immediate settings and contexts (123). This reflected my effort to stand at the nexus of their stories-so-far and possibilities of new stories.

Figure 1. Image description: a promotional poster with “The Beautiful Valley of the Lower Rio Grande” at the bottom in beige font on a black background. The image shows three men harvesting large baskets of fruit among palm trees.

######

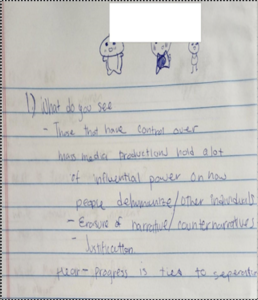

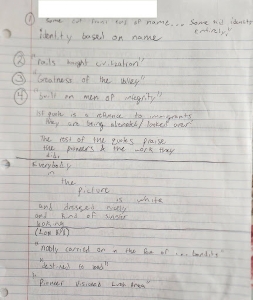

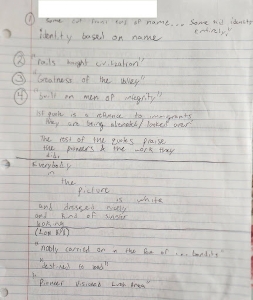

Students, to my surprise, were receptive, given the friction I encountered early on in the semester. They demonstrated their intellectual capacities to explore, investigate, analyze, interpret, determine, and translate meaning. For example, one student wrote about how settlers had control over mass media production (left image). This stood out to me given the mass management and control over multiple mediums of media in Utah and the way the war of information has influenced how “people dehumanize/other individuals.” Another student documented what they saw: white women, old white angry settlers, and white mayor. This response stood out as well because Utah is notoriously White and the rhetoric of place is “the glorification of settlers/colonialism/manifest destiny” (right image). With this settler archive I was able to underscore the effects and consequences of settler colonialism and coloniality on land, memory, knowledge, understanding, feeling, and being.

Figure 2. Image description: a piece of notebook paper with doodles of three cartoon figures at the top and a list of notes in blue ink.

Figure 3. Image description: a piece of notebook paper with a doodle of an eye with long, thick lashes at the top right. The notes, written in black ink, have the heading “1910-1960” and a list of phrases.

######

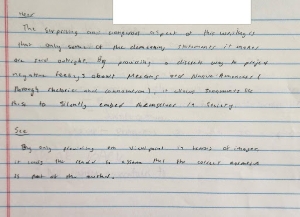

Students were keen on what they encountered in the archives. One took note of key phrases that stood out to them: “rails brought civilization” | “men of integrity” | “destined to lead.” Their observation did not go unnoticed: “Everybody in the picture is white” (left image). I say this because the course was demographically majority white church members with only a couple of exceptions. I wondered, how did students internalize all this? Did it even cross their mind? Another student comments on the “dangerous aspect of this writing” because it “allows sentiments” about “Mexicans and Native Americans” to “silently embed themselves in society” (right image). The irony of this statement is not lost on me either particularly as it is read alongside the claim, “by only providing one viewpoint…it leads the reader to assume that the correct narrative is that of the author.” Because Utah is a case study in just how that has happened. I wondered here too, if they found irony in how they dismissed the racist fliers discussed at the onset of the semester.

Figure 4. Image description: a photograph of a sheet of notebook paper with notes written in black ink: a numbered list 1 through 4 at the top, and phrases and quotations on the lower half of the page.

Figure 5. Image description: a photograph of a sheet of notebook paper with notes written in black ink: a section at the top with the heading “Hear” and notes underneath, and a section in the lower half with the heading “See” and notes underneath.

######

But this activity reflects the extent of my success that semester. By week three the language of the everyday shifted from Texas/me to Utah/Utahns. The classroom environment changed. We focused on haunting(s)-situation(s) that marked settler arrival, settlement, and expansion in Utah: the various wars between church-settlers and American Indians/Native Americans (Battle at Fort Utah, Battle Creek Massacre, Black Hawk War, Wakara’s War, Tintic War); the multiple treaties (Treaty of Abiquiú of 1849, The Spanish Fork Treaty of 1865, Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868); and coloniality of instruction-and-curriculum (Intermountain Indian School, The Indian Placement Program-Lamanite Placement Program, and Relief Society). Friction was at work. But so were many of the students. Because friction cuts both ways. Such friction laid bare the public secret of Utah, the structure of feeling haunting Utah, and the function of Utahn niceness-politeness (and not-in-Utahism); a faux listening to the Other-as-Same.[18]

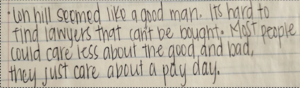

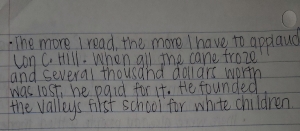

Corder anticipated moments in which people can be steadfast in convictions. Coloniality of instruction-and-curriculum had only ever underscored the structural underpinnings and material consequences of their stories-so-far. Returns to and careful reckonings with how stories-so-far and the everyday adhere to, interact with, and carry out the histories, cultural memories, and literacy-rhetorical practices settler archives represent amplify a threat to foundations of self, stories-so-far, and community. What happens in such cases? The image below comes from students responding to the Texas settler archives. Notice, the students refer to the settler as a “good man” and applaud the settler for taking risks and establishing a white school for children. Now, this comes off the heels, once more, of discussions on settler colonialism and coloniality. Utahn niceness-politeness, in this context, is the act of listening with no intention to have critique bear on the self while epistemic ignorance is the production of knowledge wielded to create distance-separation and maintain relations of power.

Figure 6. Image description: a photograph of four lines of notes written in black ink on a sheet of notebook paper

Figure 7. Image description: a photograph of four lines of notes written in black ink on a sheet of notebook paper

######

But I was persistent. We tried the privilege walk and privilege for sale activity. I invited colleagues (Christie Toth and Jon Stone) to attend class. We watched short documentaries. We listened to music. We read the words and ideas of their ancestors. I was still green in the world of teaching. And so, I tried everything. Because I refused to allow church-settler epideictic rhetoric to go unchecked; a wor(l)ding aspiration, which underscores students’ understanding of the ways words and worlding can take and make space-place. Overall, my goal was to utilize the language of the everyday, attending to the appeal by the student who emailed me, to both illuminate cultural and thinking program/ings and create friction. Hardly anything changed. But I did have four students who were doing shadow work; work behind the scenes without any guarantee or certainty for what it might yield (see Arellano et al.). By week 7 of the semester, I decided to scrap the final project and create a new one on the fly. I would call it, “Stories-So-Far and the Possibilities of New Stories.” The title would be inspired by the work of feminists such as Doreen Massey and Judy Rohrer.

Figure 8. Image description: screenshot of an assignment description document for a multimedia portfolio

Figure 9. Image description: screenshot of the second page of an assignment description document for a multimedia portfolio

######

The assignment description is rather long and imperfect but overall the goal for the final project was to create an opportunity for students to gather their ancestral stories-so-far and collect evidence to support the verisimilitude of them—demystifying and extending archival research to the elsewhere and otherwise. The inevitable friction would hopefully aid them in considering an-other set of choices, options, and obligations-responsibilities. The assignment builds on the ideas of griots, corridistas, and elders as keepers of history and knowledge, time benders, and canon makers entrusted with being the affective channels of rhetorical transmission of and for a politics of hauntings, inheritances, and dwellings. They operate under a simple premise that people can listen to know-learn complex issues if the intention is truly for them to understand. It is a portfolio assignment constituted thus by returns home, careful reckonings with stories-so-far, and the praxis of unsettling the settled. But again, things do not always go as planned. The assignment went to work, because what was at stake was a grade for students, but so too did students, because friction cuts both ways.

Unlike the scenarios Corder plays out in his essay educators do not have the luxury to walk away, the right to blame students for past atrocities, nor are they entitled to create a culture of adversaries. Still, I find myself agreeing with Corder that argument is not just a noun but a praxis of being-and-becoming, reminiscent of Sylvia Wynter’s being human as praxes. Friction holds value for me because intervention is rooted in the specificities and particularities in which power unfolds; we must know where we are at and who we are teaching. It holds two truths, first, that there is an opportunity for some-things to be-with each other, get to work on un/settling grounds, and mutually co-invent in friction in ways that can take and make place otherwise; power is un/made through friction. And second, friction can be like the fly in the elephant’s nose, which is to say, that at the very least we can be the wrench in the assembly line of normative stories-so-far. [19] The goal is not a totalistic rejection of religion nor is it to deliver conversion-type of education but rather it is to create solidarity in and around deep commitments to unsettling the barriers between us and that hoped-for future.

Sometimes neither a theory (a decolonial option) nor concept (deep rhetoricity) will go as planned in the classroom. The entirety of the semester was not all marked by failure. I was able to reach four students. The student below was affected by classroom conversations, the behavior of their classmates, and the unwillingness within group circles to have critical dialogue. So, they decided to lead blog posts anonymously which culminated into an end of the year presentation.

Figure 10. Image description: a screenshot of a slide deck with six thumbnail images on the left and the title slide on the right. The title slide is a blue-green background with “Race in Salt Lake City” in a serif font.

Figure 11. Image description: a photograph of notebook paper with notes. Some words and phrases are scribbled out, and lines and arrows are drawn to indicate moving some words from one place to another.

######

It is our hope, as educators, that when we offer an-other set of choices, options, and responsibilities students will pick it up, hold onto it, learn from it, and even pass it along. Sometimes, however, the work of our work will only be felt after the fact. So, perhaps, a reconceptualization of failure is in order, because the students I taught that semester will never be able to truly claim they never knew. And that for me is the power of being-and-thinking-with. Stories from faculty of color advancing the projects of unsettling and a decolonial option at PWIs are few and far between in WRS. So, I wanted to share a story of tension, frictions, adjustments, and failures from within the classroom.

Still, I believe feminist activist and coalitional work can benefit from deep rhetoricity. Fanon to Mahmood warned about the predicament of contaminating life questions and questions of agency with reductive, dichotomous, and oppositional rhetorical structures. There is almost a sense of simplicity that underscores the aims to unsettle the settled-ness of systems of hierarchy, patriarchy, and other forms of oppression-repression. But at the moment life and agency get reduced to binaries (black/white; good/bad; right/wrong) and options (confront; resist; re-signify hegemonic norms) that human work-project becomes unsuitable for anyone, even if resistance is what is happening. Because it presupposes the proper grounds and name for knowledge, understanding, and being; speaking the proper words and identifying a proper way, reproducing a story of the [I] and the [You] instead of the [We/arth]. Feminist activist and coalitional work still have some unsettling of the settled to do, and deep rhetoricity can aid in such endeavors.

Feminist coalitional work can benefit from deep rhetoricity insofar that it thrives in the complexities, complicatedness, and messiness that comes with friction. In fact, the epistemic principle of enduring tasks underscores the anticipation of that. For me, the wor(l)ding of a future of the [We/arth] complements Fanon’s vision for a building of the world of the [You]. [We/arth] unsettles the barriers between us and that future by embracing how [W]e all need to give an [E]ar to what lives in our bones [/] and both re-introduce (co/re)-invention as [A]rt and be receptively generous to each other and the [Earth]. [20] And yet, it nuances the [You]. First of all, wor(l)ding is what we do in WRS, because wording is human work and worlding is a human project. [We/arth], second of all, unsettles the settled-ness of proper words and identifying a proper way. It holds that rhetoric matters because it demands an engagement not just with human beings but with everything that surrounds us—[Earth]. To have [We/arth] in common is to value the possibility for commonality and radically reframe the worth (intentional homonym) of a gift in the non-name of all and for the sake of all Matter living-on [sur-vie] and flourishing otherwise.

Feminist Activist and Coalitional Work

In this section, we, the coauthors of this essay, reflect on what feminist activist and coalitional work means to us and what it can look like. Our reflections do not attempt to settle on [A] definition of feminist coalition-building but rather underscore the importance of thinking-and-being-with others (inheritances, dwellings, ghosts, people, non-humans) otherwise. Our reflections below highlight feminist Ribero and Arellano’s concept of comadrismo at best and at the very least our aspirations for the wor(l)ding otherwise.

Gesa: The feminist activist principles we describe in the introductory section of this essay have become integral to all courses I plan, design, teach, revise, or re-envision. For example, in the course discussed here, Writing the Archives, I center the readings, assignments, research methods, and research projects in feminist pedagogical principles. Although the class did not have an explicitly feminist theme, feminist activist principles inform my course design and presentation, including readings selected, questions raised about research methods, emphasis on reciprocity, respect, collaboration, and dignified relations with participants, as well as discussions of differences between stories-so-far and the possibilities of new stories. Moreover, my goal is to invite students to make meaningful contributions to new or existing archives; to consult, collaborate, and build coalitions with community members whose stories and lived experiences became the subject of their inquiry; and to contribute to conference panels or scholarly publications (such as this article).

Valeria: Coalition-building means and manifests itself through many different ways in my life. I am the start of a new generation in my family, I was the firstborn of the fourth living generation. Every time I go home it is essential to me to come to where my family started. I ask to be taught about the struggle, the sacrifice, and all the work done. I constantly visit the house where my grandmother was born. That’s where everything started. To me, it is the house that reminds me of why I need to keep going. Feminist activist and coalition work to me is paving a path for all the women in the world who are underrepresented and come from similar backgrounds as me. We are incredibly hidden in important professional sectors such as the finance field. I emphasize this because the journey I am currently on has not been easy. Coalition-building to me is sitting down and listening to the several two-hour interviews I worked with and making sure every experience was documented correctly on the UofL’s Oral History Center website because I know what it is like to have your story be told incorrectly by others. Voices are important, and making sure experiences are transmitted correctly is even more essential to advocacy, inclusion, and trust. Coalition-building is the reason why the organization Pathways to Citizenship, a 501(c)3, is now a priority in my life. Pathways to Citizenship’s mission is to help undocumented individuals navigate the complicated legal and cultural pathway to citizenship in the United States. It is essential to give back to my community and contribute to the success of the Latinx community in the United States as well as in Latin America. Every year, I distribute educational resources, food and clothes to my community in Pereira, Colombia. It is important for me to take the time to invest in others who were born into my same struggles. My success is measured through how many lives I impact, not how much profit I can make. Coalition-building to me means I do not win unless the people around me do too.

Nicole: What feminist coalition-building means to me is to be able to build not only strong but also meaningful connections with the people and communities I am working with which in my case were the Sisters. Feminist activist and coalition-building work means you’re able to find common ground and help each other in a mutual way, although sometimes you may be working with diverse communities and/or people. This was how it was with me while working with the Sisters that although a community themselves, as individuals they were extremely diverse and complex in the best of ways. I was able to learn from the Sisters while also being able to help them add to their digital archives. It was a mutual exchange and was a building of feminist coalition from both ends. To have successful feminist activist and coalitional work I wanted to represent and advocate for the Sisters. While carrying out my work this meant being able to make sure not to speak for but on behalf of the Sisters, what they shared with me was their truth and stories that I was granted access to share with others; the Sisters held the power in their voices and what I shared. I wanted others to see the more intimate side of the Sisters they don’t always get to share, and what made this feminist coalition-building really special for me is that because the Sisters are so diverse, they advocated for many other communities along with the feminist community which meant we were able to do some coalition-building for those communities as well. I always wanted to make sure that everything I did with the Sisters was done with dignity and respect.

Within my project feminist coalition-building looked like working continuously with the Sisters and constantly asking them for their feedback. With everything I did I worked closely alongside Professor Caldwell who gave me honest and very useful feedback. As a Professor and Sister themselves, their feedback meant a lot to me as they saw both perspectives and were the blend within the two parties involved. While interviewing the Sisters I made sure to not only ask my own questions but also give them the opportunity to share what they wanted to say and allow them to have liberty within the project so it wouldn’t be just a script. The coalition-building did not only come off from my end but it was a collective effort to do what was best for all involved; most importantly, the Sisters and their individual stories were the center of it all.

Romeo: At the heart of feminist rhetorical practices is an ethic, ethos, and praxis of unsettling the settled-ness of societal, cultural, and/or communal mechanisms of oppression, repression, exclusion, and erasure. Several examples in English and Writing and Rhetorical Studies come to mind that speak to coalition-building and efforts to undertake the [R] project (rescue, recover, recognize, reinscribe, and represent) in order to restore women to rhetorical history and rhetorical history to women: Walking and Talking Feminist Rhetorics (edited by Buchanan and Ryan), Rhetorica in Motion (edited by Schell and Rawson), Available Means (edited by Ritchie and Ronadl), and Feminist Rhetorical Practices (Kirsch and Royster) among others. I think Ribero and Arellano capture the connecting threads across these projects when they advocate for comadrismo. If coalition-building is going to mean anything it must include networks of care, mindsets of no te dejes, relations of trust, reciprocal empathy, and most of all love. I think of my Grandma and her comadres in this case, who exhibited for me an awaiting (“ojalá”): a hope without guaranteed predicate, a hope for that which may or may not arrive.[21]

Grandma and her comadres were more than ready to carry out work for an-other (me) without ever any certainty or guarantee for what it might yield. Not only does this speak to the ethic of paying it forward but also underscores the ethos and praxis of (rhetorical) poder y fuerza. Royster might refer to this as rhetorical prowess, but a more appropriate phrase might be a no te dejes mentality. It is best captured by the words of my Grandma, “¡No dejaremos (terconess) que cualquier cosa o persona nos trate comoquiera. Porque si lo dejas, ya valio!” That is the personification of poder y fuerza, which is not predicated on pre-commitments to idioms of resistance, subversion, and re-signification of hegemonic norms but rather reflective of the complexities of reality and to political realities; we do despite hauntings and in spite of gaining meaning from haunting situations. In other words, haunting(s)-situation(s) enable and create our capacity for action. I am not sure if the comadres I know would refer to themselves as feminist but that is not the point. Here, the point is the ethic, ethos, and praxis of coalition-building that strives to engage in a wor(l)ding of futures otherwise. And that is work worth undertaking. That is the work I hope can live-on [sur-vie] and flourish beyond our immediate settings and contexts.

Concluding Thoughts, Visions for a Future, Otherwise

Our goal in this essay is to open up a conversation on the outward facing aspect of deep rhetoricity and advance a relational framework of being-and-thinking-with others otherwise. The epistemic principles of a return situates us squarely on ways of walking and seeing the world; careful reckonings is a coming to terms with understandings of being-and-thinking-with others and reciprocity; and being-and-thinking-with is a commitment of unsettling the barriers between us and a future of mutual wor(l)ding. Our discussions strive to animate these outwards epistemic principles of deep rhetoricity amid troubling times and pedagogical challenges. In all sincerity, we have no remedy, nor do we offer a how-to guide to do this work. Yet, we believe that the concept we lay out and the outward principles we have tentatively sketched out amplify the demand to learn how to be-and-think-with each other otherwise.

As the examples from García’s and Kirsch courses illustrate, instructors always already stand at the nexus of stories-so-far and the possibilities of new stories. As García illustrates, this is an enduring task, a call for an intervention, when we become too comfortable in the settledness of our assumptions and our communities. We must continually ask, where are the lessons of ethos and praxis being proposed from? To be-and-think-with another, at least as conceived in this essay, is to engage in friction: an opportunity for non-humans (people, stories, knowledge) to come together and get to work. At times, to channel Corder, it will feel like we as educators are plunging on alone and that we might have to continue to do so as friction becomes resistance. In those instances, the barriers between us and a future of mutual wor(l)ding becomes muddy. But unlike the scenarios Corder plays out in his essay, educators do not have the luxury to walk away. In such instances, all we can do then is be the fly in the elephant’s nose. That too is a form of unsettling the barriers between us and a future,

As Kirsch’s students so eloquently narrate, the enduring task is one of making ongoing commitments to relearn to be with ourselves, others, and communities otherwise, a call for invention and co-invention. As Salazar’s and Guevara Fernandez’s research projects illustrate, taking seriously questions of ethos and praxis–reflecting on our own commitments–and of reciprocity–how we might engage with and contribute to those whose lives we study and document–will lead us to co-create spaces/ places that allow for possibilities of new stories, for creating coalitions of solidarity, and for committing ourselves and our work to bold visions of the future. If the research, ethos, and commitments of up-and-coming scholars like Guevara Fernandez and Salazar is any indication, we are well on our way to overcoming the barriers that might stand between Us and that Future.

Works Cited

“About the Sisterhood.” The Los Angeles Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, https://www.ladragnuns.org/ accessed 15 August 2023.

Acosta, Abraham. “Hinging on Exclusion and Exception: Bare Life, the US/Mexico Border, and Los Que Nunca Llegarán.” Social Text vol. 30, no. 4, 2012, pp. 103-123,

Alcoff, Linda. “An Epistemology for the Next Revolution.” Transmodernity, vol. 1, no. 2, 2011, pp. 67-78.

Alexander, M. Jacqui and Chandra Mohanty, “Cartographies of Knowledge and Power: Transnational Feminism as Radical Praxis.” Critical Transnational Feminist Praxis, edited by Amanda Swarr and Richa Nagar (SUNY Press, 2010), pp. 23–45.

Applegarth, Risa. “Children Speaking: Agency and Public Memory in the Children’s Peace Statue Project.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 47, no. 1, 2017, pp. 49-73.

Arellano, Sonia, José Cortez, and Romeo García. “Shadow Work: Witnessing Latinx Crossings in Rhetoric and Composition.” Composition Studies 49, no. 2 (2022): 31-52, p. 31.

Arvin, Maile, Eve Tuck, and Angie Morrill. “Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections between Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy.” Feminist Formations, vol. 25, no. 1, 2013, pp. 8-34.

Brasher, Jordan. Derek Alderman, and Joshua Inwood. “Applying Critical Race and Memory Studies to University Place Naming Controversies: Toward a Responsible Landscape Policy.” Papers in Applied Geography 3, no. 3-4, 2017, pp. 292-307.

Browne, Kevin (2021). A Douen Epistemology: Caribbean Memory and the Digital Archive. College English, 84(1), 33-57. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce202131451

Buchanan, Lindal, and Kathleen Ryan. Walking and Talking Feminist Rhetorics: Landmark Essays and Controversies. Parlor Press, 2010.

Bunch, Lonnie G., III. A Fool’s Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump. Smithsonian Books, 2019.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 1990.

Caswell, Michelle. “Seeing Yourself in History: Community Archives and the Fight Against Symbolic Annihilation” The Public Historian, vol 36, no 4 (2014): pp 26-37.

Cisneros, Sanra. Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories. Vintage, 1992.

Corder, Jim. “Argument as Emergence, Rhetoric as Love.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 4, no. 1, 1985, pp 16-32.

Cruz, Cindy. “Making Curriculum from Scratch: Testimonio in an Urban Classroom.” Equity & Excellence in Education vol. 45, no. 3, 2012, pp. 460–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2012.698185.

Cusicanqui, Silvia Rivera, “Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: A Reflection on the Practices and Discourses of Decolonization.” The South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 111, no. 1, 2012, pp. 95-109.

Cvetkovich, Ann. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

Dávila, Arlene. “What My Students Don’t Know about Their Own History.” Opinion: Guest Essay. The New York Times, 15 Oct. 2022.

Davis, Diane. Inessential Solidarity: Rhetoric and Foreigner Relations. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010.

Delgado Bernal, Dolores, Rebeca Burciaga, and Judith Flores Carmona. 2012. “Chicana/Latina Testimonios : Mapping the Methodological, Pedagogical, and Political.” Equity & Excellence in Education vol. 45, no. 3, 2012, pp. 363–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2012.698149

Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. Routledge, 1994.

Duplessis, Rachel Blau, and Ann Snitow, editors. The Feminist Memoir Project: Voices from Women’s Liberations, 2nd edition, Rutgers UP, 2007.

Dussel, Enrique. The Invention of the Americas: Eclipse of ‘the other’ and the Myth of Modernity. Continuum, 1995.

Endres, Danielle, and Samantha Senda-Cook. “Location Matters: The Rhetoric of Place in Protest.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 97, no. 3, 2011, pp. 257-282.

Enoch, Jessica. Refiguring Rhetorical Education: Women Teaching African American, Native American, and Chicano/a Students, 1865-1911. Southern Illinois UP, 2008.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin White Masks. Pluto Press, 1986.

Fukushima, Annie. Migrant Crossings: Witnessing Human Trafficking in the U.S. Stanford University Press, 2019.

García, Romeo. “Creating Presence from Absence and Sound from Silence.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 13, no.1, 2018, pp. 7-15.

—. “Unsettling Church(-)Settler Ideas, Images, and Ends.” Rhetoric, Politics, and Culture, vol. 1, no. 2, 2022a, pp. 1-46.

—. “Decolonizing the Rhetoric of Church-Settlers.” Unsettling Archival Research: Engaging Critical, Communal, and Digital Archives, edited by Gesa Kirsch, Romeo García, Dakota Smith, and Caitlin Burns. Special Issue of Across the Disciplines, vol. 18, no. 1/2, 2022b, pp. 124-144.

—. “Personal and Collective Memory as Shadow Work.” Cross-Talking with an American Academic of Color, edited by Asao B. Inoue, Siskanna Naynaha, and Wendy Olson. SWR Series, 2023.

—. Making it Out (Under Contract, Utah State University Press).

García, Romeo, and Gesa E. Kirsch. “Deep Rhetoricity as Methodological Grounds for Unsettling Archival Research.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 74, no. 2, 2022, pp. 230-62.

García, Romeo, and José Cortez. “The Trace of a Mark that Scatters: The Anthropoi and the Rhetoric of Decoloniality.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly vol. 50, no. 2, 2020, pp. 93-108.

Giddens, Anthony. A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism (vol. 1: Power, Property, and the State). University of California Press, 1981.

Gilligan, Carol. “Moral Injury and the Ethic of Care: Reframing the Conversation about Differences.” Journal of Social Philosophy, vol. 45, no.1, 2014, pp. 89-106.

Glenn, Cheryl. Rhetoric retold: Regendering the tradition from antiquity through the Renaissance. Southern Illinois UP, 1997.

Gordon, Avery. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. University of Minnesota P., 2008.