A Question of Affect: A Queer Reading of Institutional Nondiscrimination Statements at Texas Public Universities

A Question of Affect: A Queer Reading of Institutional Nondiscrimination Statements at Texas Public Universities

Peitho Volume 24 Issue 2, Winter 2022

Author(s): Sarah Dwyer

Sarah Dwyer (they/them) is a Lecturer in the English program at Texas A&M University – San Antonio and a PhD candidate in the Technical Communication and Rhetoric program at Texas Tech University. Their teaching, scholarship, and service is focused on engaging the structures that maintain and bolster the exclusionary practices of heteronormativity, racism, and classism within the academy, particularly for LGBTQ+ students, faculty, and staff. Their work on using game-based pedagogy to disrupt traditional classroom structures and encourage engagement and critical thinking has appeared in Double Helix.

Abstract: Grounded in my embodied experiences as an openly-queer faculty member at a Texas public university and drawing from Sara Ahmed’s work on affect and institutional diversity, I argue that nondiscrimination statements at Texas public universities are affective objects which serve as straightening devices on the queer bodies that they affect, even as they purport to and often do protect them. The goals of my critique are twofold: 1) to support the work of those tasked with writing revisions to these policies by offering a few practical suggestions to allow for greater enforcement of the nondiscrimination practices that these policies espouse; and, 2) to encourage further reflection on the creation, implementation, and maintenance of these policies in light of their status as living documents which have real, material consequences for the LGBTQ+ individuals who live, learn, and work in our institutions.

Tags: affect, embodiment, institutional critique, LGBTQ+, queer studiesIntroduction: Queer Moments in Texas

Being queer in Texas is a curious experience. LGBTQ+ people make up approximately 4.1% of the population—around 770,000 adults and 158,500 youth in 2017 (Mallory et al.). However, until the June 15th, 2020 ruling by the Supreme Court that Title VII protections included LGBTQ+ workers, no state or federal nondiscrimination protections existed for LGBTQ+ individuals in Texas [1]. While some cities had LGBTQ+ nondiscrimination policies in place prior to 2020, these were and remain quite limited. At legislative and institutional levels, Texas has historically been unsympathetic to LGBTQ+ interests, with the state government being particularly hostile to the transgender community in recent years. Additionally, in 2017, Texas ranked thirty-ninth in the nation on public support for LGBTQ+ acceptance and rights, while in 2021, the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) State Equality Index, an “annual comprehensive state-by-state report that provides a review of statewide laws and policies that affect LGBTQ+ people and their families,” scored Texas in the lowest-rated category, “High Priority to Achieve Basic Equality” (Mallory et al.; HRC Foundation).

In Texas, as in the twenty-six other states currently lacking statewide nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ+ individuals, what few nondiscrimination protections exist have been tied to where we live and, until recently, where we work. The physical locations of our bodies have been intrinsic to how we experience and navigate the world. Because of this, I had some reservations in 2016, when I received an offer from my current employer, part of a large university system that was simultaneously undergoing a major downward expansion and pursuing Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) designation. While I was considering the offer, I perused the institution’s website, only to discover that I couldn’t find the campus nondiscrimination policy anywhere: an immediate red flag for someone who openly identifies as queer. When I asked about it, I was sent a link to the system policy, which suggested to me that the campus nondiscrimination policy was something of an afterthought, despite the large number of minority students that the institution served. In 2016, eighty percent of the inaugural freshman class and seventy percent of the overall student body identified as Hispanic, and seventy-three percent of enrolled students were the first in their families to attend college (University Communications; Office of Institutional Research). As Porter et al. have noted, what is present on (or absent from) an institution’s webpage, reflects that institution’s identity and priorities (620). These websites are part of institutional discourses, which establish institutional identities and practices, and are a means by which institutions legitimize and justify their existence (Mayr 2). If diversity were as important to the institution’s identity as indicated by the designation it sought and by the population it served, why wasn’t the nondiscrimination statement already present on the university’s website, especially as it was undergoing a massive recruitment process for new faculty and its first class of freshmen? [2]

There is an additional peculiarity to being a queer faculty member at a public institution in Texas, especially one that does queer work: we are often outed by state policy. House Bill No. 2504, originally passed in 2009, requires that public institutions of higher education post the curriculum vitae of each instructor on their websites. CVs must be “accessible from the institution’s…home page by use of not more than three links; searchable by keywords and phrases; and accessible to the public without requiring registration or use of a user name, a password, or another user identification” and list the instructor’s “postsecondary education, teaching experience, and significant professional publications” (“H.B. No. 2504”). For faculty whose work concerns LGBTQ+ themes and issues, this can act as a form of public outing—one that I was not warned about when I was hired.

These experiences during my hiring, along with being the first openly transgender faculty member on my campus and then co-chair of Rainbow P.A.W.S. (Pride at Work and School), the faculty and staff LGBTQ+ group, led me to further question how institutional policies affect LGBTQ+ individuals at Texas public institutions. These policies are the means through which institutional perceptions of diversity are constructed (Iverson 152), yet perceptions and actual experiences of diversity on campus are very different things. In 2018 alone, Texas public institutions educated approximately 658,219 students, an unknown number of whom may identify as LGBTQ+, as there are approximately 928,500 LGBTQ+ individuals in Texas by current estimates (“Texas Higher Ed Enrollments”; Mallory et al.). For LGBTQ+ students, the campus environment, including institutional policies and programming, “has a direct effect on students’ outcomes and can mediate the effects of [negative] inputs [from the wider culture]” (Woodford, Joslin, and Renn 69). My experience working with LGBTQ+ students bears this out: I’ve often been told that they feel more comfortable being out on campus than anywhere else in their lives, even as they sometimes struggle with system policies and technologies regarding LGBTQ+ identities, such as preferred names and pronouns. Because our students feel safe on campus, it is our obligation to do all that we can to be worthy of that trust: to support them both in and out of the classroom and to revise our institutional policies and practices in ways that reflect our embodied experiences as queer individuals studying, working, and living in the strange and often hostile environment that is the state of Texas.

The Project

To answer my questions regarding institutional policies and LGBTQ+ populations, in late 2017 to early 2018, I assembled a corpus of thirty-five nondiscrimination statements from the websites of Texas public universities to analyze them from an LGBTQ+ perspective. I tracked the location of the nondiscrimination statements on each institution’s website, the number of clicks it took from the homepage to access them, whether or not the statements contained any references to gender identity or expression, and related information such as the presence of an LGBTQ+ student group and diversity offices on campus.

The nondiscrimination statements were often difficult to find—it took me three or more clicks from the homepage to locate the nondiscrimination statements for 13 out of the 35 institutions, and in some cases, I had to run a search in order to find them. They were often inconsistently presented, with different versions of the statements appearing on different pages of the website. This left me wondering what the correct version of the policy was, especially because the differences between these statements generally concerned gender identity and expression—that is, some versions of the statements included them as protected categories, while others did not. The statements themselves proved problematic in a number of ways, which I elaborate upon in my analysis below, and the presence of LGBTQ+ student groups and diversity offices on campus also proved somewhat difficult to confirm. While most institutions had a clearly-named student group, in three instances I couldn’t actually find one, and I could only confirm the presence of twenty diversity offices within the thirty-five institutions I analyzed.

Based on these findings, grounded in Sara Ahmed’s work on affect and institutional diversity, and drawing on my experiences as an openly-queer person working at a public university in Texas, I argue that nondiscrimination statements at Texas public universities are affective objects which serve as straightening devices on the queer bodies that they affect, even as they purport to and often do protect them.

I begin my discussion with a brief review of affect, how I conceptualize its relationship to queer bodies and institutions, and how institutional nondiscrimination statements act as straightening devices for queer bodies. Next, I provide a brief overview of Texas public universities before analyzing three different models of nondiscrimination statements that I discovered in my research, which I have dubbed the Equal Opportunity Model, the Discrimination Prohibition Model, and the Additional Model. I also analyze the presence and absence of gender identity and gender expression statements as part of these nondiscrimination statements and conclude with a few suggestions for how these statements might be improved.

These statements can only be improved; they cannot truly be fixed, especially not by those tasked with writing revisions to these policies. The goals of my critique are twofold: to support the work of those tasked with writing revisions to these policies by offering a few practical suggestions to allow for greater enforcement of the nondiscrimination practices that these policies espouse and to encourage further reflection on the creation, implementation, and maintenance of these policies in light of their status as living documents which have real, material consequences for the LGBTQ+ individuals who live, learn, and work in our institutions.

Affect, Ahmed, and Objects

Melissa Gregg and Gregory Seigworth describe affect as “aris[ing] in the midst of in-between-ness: in the capacities to act and be acted upon…found in those intensities that pass body to body…in those resonances that circulate about, between, and sometimes stick to bodies and worlds, and in the very passages or variations between these intensities and resonances themselves” (1, emphasis in orig.). Affect occurs between bodies, between moments, between words. Sara Ahmed describes “Affect [as] contact: we are affected by “what” we come in contact with” (Queer Phenomenology 2). Affect is fluid, changeable, sticky, embodied: there is something inherently queer in its unsettledness, in its action, its permanently fleeting state. Affect exists “in the regularly hidden-in-plain sight politically engaged work…that attends to the hard and fast materialities, as well as the fleeting and flowing ephemera, of the daily and the workaday, of everyday and every-night life, and of ‘experience’” (Gregg and Seigworth 7). That is the work of this project—to consider the implications and absences of documents that are generally considered mundane matters of legal and political necessity and the bodies that they affect.

The nondiscrimination documents and diversity discourses of our institutions circle about, between, and stick to bodies like mine, which need nondiscrimination protections due to the historical failure of state and national governments to create or enforce such protections. For example, the 2020 Supreme Court Title VII ruling only applies to employment discrimination, after all. In Texas, we dwell in a “legal landscape and social climate… [that] likely contributes to an environment in which LGBT people experience stigma and discrimination [which] can take many forms, including discrimination and harassment in employment and other settings; bullying and family rejection of LGBT youth; overrepresentation in the criminal justice system; and violence” (Mallory et al.). All of this affects us in physical, material ways. The first real moment of affect between myself and my institution occurred because of the simultaneous presence/absence of the nondiscrimination statement on the university homepage, which was materially tied to both my queer body and the institution’s body, as the administration was attempting to recruit me to it. This affective relationship continues to this day, as I am visibly out on campus in a number of ways, including through my publicly-posted CV, my work with Rainbow P.A.W.S., the pronouns and title that I use, and my office (a visible representation of my place at the university, a place where my queer body can regularly be found), awash in varying shades of rainbow. This visibility is both involuntary and voluntary, and carefully negotiated: my way of navigating through the “working closet,”[3] heavily impacted by the federal, state, and institutional policies and discourses that affect how I experience the world.

These institutional policies, discourses, and nondiscrimination statements are affective objects. “Affect is what sticks, or what sustains or preserves the connection between ideas, values, and objects” (Ahmed, “Happy Objects” 29, emphasis mine). Institutional nondiscrimination statements address the idea of legal protections for marginalized people based on the institution’s espoused values, and the object(s) of these ideas and values are the bodies of those affected by them. As affective objects, nondiscrimination statements are “imbued with positive affect” (Ahmed, “Happy Objects” 34). They are “sticky because they are already attributed as being good or bad, as being the cause of happiness or unhappiness” (Ahmed, “Happy Objects” 35). While institutional artefacts such as nondiscrimination statements’ diversity policies are ostensibly “good” objects, they do not always serve the needs of the populations they purport to protect, as scholars in disability studies such as Stephanie Kerschbaum and Robert McRuer have discussed.[4]

Through embodied experiences with these policies, we may “become alienated—out of line with an affective community—when we do not experience pleasure from proximity to objects that are already attributed as being good,” a process which Ahmed describes in 2012’s On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life (37). The diversity workers she interviewed reported feelings of alienation and isolation in doing their work: continually running into the “brick wall” of the belief that doing diversity work meant professing diversity, rather than taking material action to create more equitable institutions (174-175). Nondiscrimination statements and diversity policies are objects through which institutions can profess diversity, and these objects are good because they are doing diversity work. Through my critique of these “good” affective objects, I become one of Ahmed’s affect aliens, because critiquing these documents means critiquing the institution itself and its good intentions.[5]

I am affected by these objects, surrounded by them, and in a position to analyze and evaluate them because of my queer body—they are stuck to me. Yet it is not on me to solve the problems with these objects—I am solely here to “queer the discourse of diversity,” to borrow Liz Morrish and Kathleen O’Mara’s phrasing. It is, after all, “not up to queers to disorientate straights… disorientation [can be] an effect of how we do politics, which in turn is shaped by the prior matter of simply how we live” – through embodiment and experience (Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology 177). My job is not to fix the problem; instead, it is to explain how and why it is a problem. As the former co-chair and current secretary of Rainbow P.A.W.S., formerly the LGBTQ+ Task Force at our campus, my duty entails problematizing things for my institution to encourage changes that will positively affect myself and the other queer folx on campus.[6]

Institutional Nondiscrimination Statements as Straightening Devices

Diversity, as defined by institutional discourses, is something that is brought to the institution by individual students, staff, and faculty, which contributes to the greater good (Urciuoli 165). Institutional policies frame diversity as “a goal to work toward or a commodity to accumulate” (Kerschbaum 25-26) such that diversity becomes “a marketable signifier—its invocation masquerades as the cultural capital of the university, to be bestowed on all who tread within its walls and resonating with the promise of corporate success” (Morrish and O’Mara 978). Minority bodies, including queer ones, are the means by which the institution “becomes diverse.” Institutional diversity documents such as nondiscrimination statements, diversity policies, and Safe Space stickers frequently become the instruments of this commodification, framing diverse bodies as objects for institutions to acquire and display. [7]

These documents have historically acted as straightening devices and they continue to do so. They serve to enfold an ill-fitting body (one that is non-normative according to the cultures of the institution, one that is queer) into the institution. As Roderick Ferguson explains, “From the social movements of the fifties and sixties until the present day, networks of power have attempted to work through and with minority difference and culture, trying to redirect originally insurgent formations and deliver them to the normative ideals and protocols of state, capital, and academy” (8). Title VII and Title IX, the legal documents that created the precedent for present-day nondiscrimination statements, are the direct result of the Civil Rights struggles of the 1960s and underwent the same process of normativity. Just as the revolutionary student movements of the 1960s and 1970s led to the creation of ethnic, women’s, and queer studies departments within the academy, folding them into the institution’s power and body, institutional nondiscrimination statements both provide support for and act to straighten minority students, staff, and faculty, aligning them with the whole. Or, as Ahmed puts it, “One fits, and in the act of fitting, the surfaces of bodies disappear from view” (Queer Phenomenology 134). Individuals like myself—nonbinary, asexual, and aromantic—frequently disappear even from queer conversations; by becoming part of the institution’s body, we may as well not exist at all.

This history of straightening is present in the structure of the nondiscrimination statements I analyzed, which frequently echo the wording of both Title VII and Title IX. Title VII reads “It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual…because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin” (“Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964”). Title IX, passed in 1972, reads “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance” (“Title IX and Sex Discrimination”). Although these laws were originally intended to address only issues of sex and racial discrimination in education and employment, they have since been interpreted more broadly, most recently in favor of protections for LGBTQ+ workers, as of June 15th, 2020.

Derived from these laws, universities have developed individual nondiscrimination statements that both comply with the law and establish institutional attitudes towards diversity. However, as Ahmed explains, “Universities often describe their missions by drawing on the languages of diversity as well as equality. But using the language does not translate into creating diverse or equal environments. This ‘not translation’ is something we experience: it is a gap between a symbolic commitment and a lived reality,” a gap which those of us who are LGBTQ+ on campus frequently experience (Living a Feminist Life 90). Once, I was dropping off flyers advertising one of our Safe Space sessions to the secretary of a department not my own and explained that this was training to help support our LGBTQ+ students. The person to whom I was speaking replied, “what’s that?” This moment of affect impacted my body on a physical level—for a moment, I literally couldn’t process what I was hearing; I was so dumbfounded by the idea that someone didn’t know what the LGBTQ+ acronym meant. This was not-translation in a literal sense: at that moment of exchange, we were speaking two different languages.

Although generally in a less literal form than this example, nondiscrimination statements can become the means through which this “not translation” occurs, particularly because they serve as a one-size-fits-all solution to the inherently personal problem of discrimination on campus. The issues I face on campus as a white, DFAB,[8] mostly-abled, agender individual, are quite different than those of my cisgender, heterosexual, Black best friend, a Jamaican immigrant who is also a lecturer in our program, yet the same nondiscrimination statement is ostensibly meant to protect us both, even though our needs and experiences are very different.

Symbolic commitments to diversity are not enough for people who are affected by these statements, whose responses to these documents and discourses are inherently personal and embodied. Creating these documents is not enough: we must critique, revise, and continually adapt them to better serve the needs of both our students and ourselves.

An Overview of Texas Public Institutions

Texas has six public university systems: the A&M system (eleven institutions), the University of Texas system (eight institutions, six medical centers), the University of Houston system (four institutions), the University of North Texas system (two institutions, two medical centers), the loosely-affiliated Texas State system (four institutions), and the Texas Tech system (two institutions, two medical centers). There are four independent public universities: Midwestern State University, Stephen F. Austin State University, Texas Southern University, and Texas Woman’s University.

As I reviewed each institution’s website, I encountered three general models of nondiscrimination statements: one focused on equal opportunity, one focused on prohibiting discrimination, and a third model, which was a variation on the other two. In all cases, Title VII and Title IX defined the list of protected classes included in these statements, and institutions frequently included additional protected classes that were at the time not yet defined by law: sexual orientation, gender identity, and occasionally gender expression. While some of these nondiscrimination statements have been updated since the time of data collection, many remain the same.

Diversity Statement Model 1: Equal Opportunity Model

Statements in this model were worded as follows: “[Institution] provides/will provide equal opportunity without regard to/regardless of [list of protected classes].”

Table 1: Institutions using the Equal Opportunity Model

| System | Total Institutions | Number Using the Equal Opportunity Model |

| Texas A&M | 11 | 8 |

| University of Houston | 4 | 4 |

| University of Texas | 8 institutions, 6 medical centers | 2 |

| Midwestern State University (Independent) | 1 | 1 |

This form of nondiscrimination statement is framed in a positive manner, based on providing equal opportunity to all, rather than on forbidding unlawful employment practices. This model is perhaps the simplest and most positively phrased, and thus the most politically neutral; rather than defining any sort of prohibition, it only promises that “equal opportunity” will be afforded to traditionally marginalized groups. This phrasing obfuscates the actual legal obligations of the institution in terms of protecting marginalized bodies and does not offer explicit protections for those that it affects. It also fails to define any prohibitions against discrimination, though these may be described elsewhere in other policy documents.

The phrasing of this form of nondiscrimination statement raises a number of questions. How is “equal opportunity” defined at the institution? How does one provide evidence that they have not been offered an equal opportunity as someone else? In such cases one must out themself to administrators, much as disabled individuals must when requesting legally-required accommodations, an institutional practice which disability studies scholars have described as “a bureaucratic act further perpetuating different manifestations of institutionalized discrimination” (Carrol-Miranda 281).

Further questions arise when we consider the issue of embodiment: what does equal opportunity without regard to or regardless of identity mean? I am a queer faculty member, doing queer work at my institution. My ability to do this work is intrinsically tied to my identity; it affects my experiences, my teaching and service and scholarship—so what does it mean if my experiences and knowledge go without regard? For scholars focused on identity—scholars of color, queer scholars, feminist scholars, disabled scholars—our work is intrinsically tied to our embodied experiences of the world. If a position arises that is connected to issues of identity, should it truly be an opportunity that is offered equally to all? Several years ago, our then-named LGBTQ+ Task Force collectively decided that at least one queer individual needed to serve as co-chair of the committee at all times. Was this an equal opportunity? Should it have been one?

These questions are theoretical until the moment that these policies affect someone, affect their embodied experience of the world, and connect (or disconnect) them from the body of their institution.

Institutional nondiscrimination statements affect bodies: they serve as a form of straightening device by enfolding disparate groups together and putting them together under the shared umbrella of diversity, eliding the differences between them. The marginalized members of diverse groups, with different needs and experiences, are offered “equal opportunity,” a vague term which is assumed to address all these disparate needs. And what of intersectionality? Many institutions will happily tout their diversity credentials while their campuses remain inaccessible for anyone with a physical disability: I once spent a semester on crutches, unable to access my department, located on the third floor of a building with no elevator. Although my classes were relocated to buildings with elevator access, I was once asked if I could hobble up the stairs to the third floor to make it to a class that had been rescheduled.[9] Another time, a fire drill occurred while I was on the fourth floor of the library. The elevators had been shut down, and while I stood there, presumably burning to death, I had some pointed questions for the building staff about evacuation plans for the disabled. Their answer was a politely baffled silence.

These issues had nothing to do with my queerness, but everything to do with my body: non-normative, affected once again by institutional policies that didn’t account for me. What is “equal” about that?

In the wording of this model, even the potential for wrongdoing is obfuscated: the institution offers “equal opportunity,” which implies that no discrimination could ever occur, since opportunity is offered equally to all. While this suggests that the institution considers ensuring equal opportunity to be a moral obligation, the fact of the matter is more prosaic: every institution must have policies in place to deal with such situations because they can, do, and will occur, regardless of the good intentions of the creators of such policies.

Diversity Statement Model 2: Discrimination Prohibition Model

Statements in this model were worded as follows: “[Institution] does not discriminate/discrimination is prohibited on the basis of [list of protected classes].”

Table 2 : Institutions using the Discrimination Prohibition Model

| System | Total Institutions | Number Using the Discrimination Prohibition Model |

| Texas A&M | 11 | 3 |

| University of Texas | 8 institutions, 6 medical centers | 1 |

| University of North Texas | 2 institutions, 2 medical centers | 4 |

| Texas State | 4 | 4 |

| Texas Woman’s University (Independent) | 1 | 1 |

This form of nondiscrimination statement, rather than offering vague promises of equal opportunity, is more explicit about the institution’s legal obligation to prohibit discriminatory practices and bears a stronger resemblance to the phrasing of both Title IX and Title VII than the previous model does. Because of their emphasis on prohibiting discriminatory acts, these nondiscrimination statements seem to have a bit more weight to them. It may be easier to define what counts as a discriminatory act than what counts as “equal opportunity,” given that most institutions have established working definitions for what constitutes discriminatory behavior, usually found on the policy statements page, Title IX, EEO, or HR pages. Likewise, potential consequences of discriminatory behavior are generally explicitly stated within these policies. Because these policies define clearer boundaries, institutional agents may more easily enforce them.

This model of nondiscrimination statement implies a different sort of protection than the previous one, yet still acts as a form of straightening device for the bodies that it affects. Like the previous model, it provides protection for the institution, keeping it in line with federal requirements, and this increased legal emphasis serves to distance it from the very people that it affects. Likewise, the list of marginalized categories still groups disparate individuals together under the same ill-fitting umbrella. One major difference between this and the previous model, however, is that the increased legalese of the phrasing implies that protections for marginalized populations are a legal obligation for institutions, rather than a moral one.

However, these legal protections have their limits. While an institution may prohibit discrimination, the people who are part of the institution are often the ones who commit discriminatory acts, whose words and actions have physical and material consequences for the LGBTQ+ population on campus. Legal protections can do very little when the perpetrators of such actions cannot be found. When I was initially collecting the data for this project, the Coalition, the student LGBTQ+ group, hosted Drag Show Loteria as part of Coming Out Week and posted flyers around campus advertising the event. Several of these posters were defaced by persons unknown—an act of clear anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination, but one which went unpunished because there was no mechanism for tracking down the vandals and applying the appropriate sanctions, as A&M system policy states that discrimination is “a materially adverse action or actions that intentionally or unintentionally excludes one from full participation in, denies the benefits of, or affects the terms and conditions of employment or access to educational or institutional programs” (“System Regulation 08.01.01, Civil Rights Compliance”). An act of vandalism such as this, while clearly a discriminatory action—one that had a significant negative affect on the Coalition members who had to deal with the situation, one which was intended to make them feel unwelcome and potentially concerned about their physical safety while on campus—may not be considered as such per system policy.

This is precisely the problem with documents that focus on the legal issue of discrimination: they may not be enforceable given institutional policies and structures, and they provide little to no guidance on how to protect our bodies and work from discrimination coming from nebulous agents within our institutions, to say nothing of those from the outside. In 2020, two virtual public events hosted by our campus were Zoom-bombed by racist groups which played pornographic videos and filled the chat with discriminatory slurs—acts which caused significant distress for participants, acts which, although virtual, affected their feelings of safety and security at our institution. In the wake of these incidents, security guidelines for public online events were clarified and strengthened, yet once again, the perpetrators were never caught.

Diversity Statement Model 3: Additional Model

Statements in this model were worded as follows: “[Institution] provides equal opportunity/does not discriminate based on [list of federally protected classes]. Additionally, [Institution] does not discriminate on the basis of [list of additional classes].”

Table 3: Institutions using the Additional Model

| System | Total Institutions | Number Using the Additional Model |

| University of Texas | 8 institutions, 6 medical centers | 5 |

| Texas Tech | 2 institutions, 2 medical centers | 2 |

| Texas Southern University (Independent) | 1 | 1 |

| Stephen F. Austin State University (Independent) | 1 | 1 |

The third model of nondiscrimination statement lists additional protected categories in a separate sentence, rather than adding them to the end of the existing list. The Texas Tech system had a slightly altered take on this phrasing:

Texas Tech University does not tolerate discrimination or harassment of students based on or related to sex, race, national origin, religion, age, disability, protected veteran status, or other protected categories, classes, or characteristics. While sexual orientation and gender identity are not protected categories under state or federal law, it is Texas Tech University policy not to discriminate on this basis. (“Title IX”)

Since the Supreme Court ruling of June 15, 2020, sexual orientation and gender identity are now considered federally protected categories, at least in regards to Title VII.

This model echoes the other two models, including both the vagaries of “equal opportunity” and the legalese of “does not discriminate.” This phrasing highlights both the changing nature of the politics of nondiscrimination and the institution’s professed dedication to diversity and emphasizes that LGBTQ+ individuals were protected by their institutions, even when unprotected by state or federal law. Though this phrasing acknowledges the unique status of LGBTQ+ individuals and serves as an institutional critique of broader American culture and politics, it may also be an indication of the tokenism that occurs when diverse bodies are used as props to illustrate how inclusive an institution is, or at least how the marketing department would like it to appear.

This form of diversity statement showcases the bodies that these policies affect most explicitly and additionally. While these statements imply a critique of the larger social problems facing LGBTQ+ individuals, this phrasing also suggests that these extra bodies—these queer bodies—are ancillary, an afterthought. The double-edged sword faces us once again: as LGBTQ+ individuals, we are in a unique situation regarding current nondiscrimination laws, which until recently have been dependent on whatever local and institutional policies applied to our physical locations. Local nondiscrimination laws frequently only apply to individuals employed by or contracted with the city, and as employees of Texas public universities, we work for the state. Thus, no such laws applied to us until the Supreme Court’s Title VII ruling, and even then, one of the first studies of LGBT employees since this ruling found that “nine percent of LGBT employees…were fired or not hired because of their sexual orientation or gender identity in the past year” (Sears et al.). The policies that our institutions have created have often been our only form of nondiscrimination protection and are only effective when enforced. They both acknowledge and obfuscate the complexities of our positions: a queerness inherent to our very existence.

The phrasing of this form of nondiscrimination statement both explicitly acknowledges the unique circumstances of the queer body within the institution and larger society and most explicitly renders our bodies as a form of diversity currency, which the institution can call upon to illustrate its (supposed) commitment to diversity. Our presence on campus is often used as a recruitment and marketing tool: at my institution, small banners, which feature images that illustrate the diversity of our campus, adorn the lampposts. One such image features the Coalition, our LGBTQ+ student group. While this image helps to advertise an important student organization, I also consider it somewhat exploitative of an already-marginalized population, especially because the composition of some of the images used for this purpose have a whiff of what disability rights activists call “inspiration porn.”[10] Likewise, while we celebrated the addition of a rainbow crosswalk to our campus in the spring, we were less appreciative of its location—a walkway between two different parking lots, far from any campus buildings.

Unlike the other forms of nondiscrimination statements, this version does not “straighten” queer bodies by lumping them in with other marginalized bodies. However, the overall purposes of the nondiscrimination statement remain the same: to provide a normative structure through which to manage an abnormal body and to formalize and ritualize extremely personal experiences of discrimination through a bureaucratic process that serves the needs of the institution. This very action is a form of homonormativity,[11] of straightening, and can also be found within many additional diversity policies. How many institutions will offer health insurance and other benefits to the same-sex partner of a queer employee, but only if they are legally married? Such policies assume that the goal of any partnership is marriage and children, despite the fact that this is not the case even for many heterosexual couples. What of those who are queer enough that they do not fit even within those boundaries? My household is entirely queer—my queerplatonic partner and I are both agender, aromantic, and asexual—but because we refuse to engage with an amatonormative, allonormative institution such as marriage,[12] my benefits cannot extend to them, despite our nearly seven-year partnership.

Policies such as these may consider me “additional,” but when even other members of the queer community sometimes fail to recognize my identity and partnership, am I even that?

Diversity Statements and the Issue of Gender Identity

Another issue with nondiscrimination statements concerns statements of gender identity and expression. Of the thirty-five nondiscrimination statements I analyzed, thirty-two included a gender identity statement [13]. The three that did not (Tarleton State University, part of the A&M System; UT Arlington; and UT Tyler) failed to do so even when the system policy did include one.

All thirty-five nondiscrimination statements utilized the phrases “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” to demarcate these particular protected categories. However, as Morrish and O’Mara point out, such phrasing is deliberately vague: “the specifics of sexual identities are erased in favor of sexual orientation…gender has an identity, a binary identity, although the transgender identity rarely appears” (984). This phrasing acts as a straightening device: it names the protected categories without specifying what they might look like or drawing undue attention to non-normative forms of being. This creates a relatively streamlined nondiscrimination statement that allows for broad categories that may be applied to a number of different contexts but also folds non-normative sexualities and gender identities into categories that also include heterosexual and cisgender identities.

The presence and absence of such gender identity statements are a reflection of the nebulous ways in which transgender individuals are treated in our society. As a matter of legal precedent, the Supreme Court only recently declared that gender identity is a protected category under Title VII, as it falls within the larger protections guaranteed to individuals regarding discrimination on the basis of physical sex. The bodies that are or fail to be acknowledged by gender identity statements are those that deviate from the gender binary: those who are transgender or those who are intersex in any of the many ways there are to be.[14]For individuals like myself, who are not “traditionally” trans,*[15] “gender identity” means many different things: I don’t have a gender identity, so am I actually protected at all by these policies? What does that protection look like when instances of misgendering are so prevalent on our campus?

Even if gender identity is considered a protected category in an institution’s nondiscrimination statement, that does not mean the individuals who make up the institution are well-educated enough on the matter to refrain from discriminatory actions. The nondiscrimination statement for our campus, which does currently include gender identity and expression, allows me to openly identify as agender on campus and to freely use they/them pronouns and the title Mx. without fear of reprisal, but I’m still misgendered on a daily basis, even by people who should know better. Two years ago, I asked our then-department chair to contact HR on my behalf to correct the title on all of my paperwork from “Ms.” to “Mx.” All of the official paperwork I have received from HR since then has used the appropriate title, but another colleague had to contact the manager of our departmental webpage three separate times to get the correct title listed there. While this is an example of gender identity protections actively being enforced, communication breakdowns still occur: in 2020 I received a formal letter from our dean which addressed me as “Ms.,” and two months ago I received one from the Provost’s office which did the same: more moments of unsettling affect, when my physical body was once again mislabeled by my institution. While the Provost’s office now has the correct title on file, the burden was on myself and my department chair to request the correction—and this was simply an instance of misgendering in a formal letter, a form of private communication, albeit one which I had to disclose to my superiors to ensure it would not happen again. It could have been much worse: other transgender individuals have been addressed with the wrong title in campus media, and experienced significant dysphoria—an affective moment of mental and physical stress—as a result of being misgendered in front of what was effectively the whole campus.

Such failures of recognition are often the result of ignorance and the inherent complexities and problematics of trying to create an enforceable policy which protects everyone, or at least attempts to. However, these honest mistakes and oversights still have a real, immediate, and physical affect on those who experience them. While I was the first openly transgender faculty member on campus, I am not the only openly transgender employee, and my colleagues’ experiences of misgendering and transphobia on campus have been very different from mine. This is likely because of our different positions: students are generally more willing to be confrontational with staff than faculty, and no nondiscrimination policy, no matter how thorough, can account for the simple differences in power dynamics that we experience because of what we do for our institution.

While statements regarding gender identity are necessary to protect LGBTQ+ individuals on campus, significant problems occur if these statements are lacking, misplaced, or otherwise difficult to find. If system policies say protections exist for gender identity, why do some individual institutional statements fail to include them? In the case of a discrimination complaint, which policy applies? Why are the statements different in the first place?

Some of this is simple human error—keeping institutional webpages and records up-to-date is incredibly difficult. Yet the lack of gender identity in some of these statements alarms me, even though, in every case, it is a protected category within the system policy. It is the “additionally” concern once again: the aspect of my queerness that is most likely to receive pushback is an afterthought, a secondary concern, when even now, in 2022, it is what puts me in the most danger. The Williams Institute’s 2021 study of LGBT employees found that “nearly half (48.8%) of transgender employees reported experiencing discrimination based on their LGBT status compared to 27.8% of cisgender LGB employees. More specifically, over twice as many transgender employees reported not being hired (43.9%) because of their LGBT status compared to LGB employees (21.5%)” (Sears et al.).

Diversity Statements and the Issue of Gender Expression

The most concerning issue I encountered in my analysis regarded statements of gender expression. Of the thirty-five nondiscrimination statements I collected, twenty-one did not include any explicit statements about gender expression, though many of the current versions of these statements do.

Table 4: Institutions lacking a Gender Expression Statement

| System | Total Institutions | Institutions Lacking a Gender Expression Statement |

| Texas A&M | 11 | 11 |

| University of Texas | 8 institutions, 6 medical centers | 4 |

| Texas State | 4 | 3 |

| Texas Tech | 2 institutions, 2 medical centers | 4 |

| Midwestern State University (Independent) | 1 | 1 |

Outside the LGBTQ+ community, there is little recognition that gender identity and gender expression are not the same thing. But for any transgender individual, the difference is very real: a closeted transgender individual is still trans* and should have that identity respected regardless of how they present themselves to the world. A transgender individual who does not “pass” as cisgender should still have their identity respected. And what of the nonbinary folx like myself? Is our gender expression still respected, especially for those who may present as male one day, female the next, and androgynous the third? At institutions where gender expression is not a protected category, even if gender identity is, we must all proceed with caution.

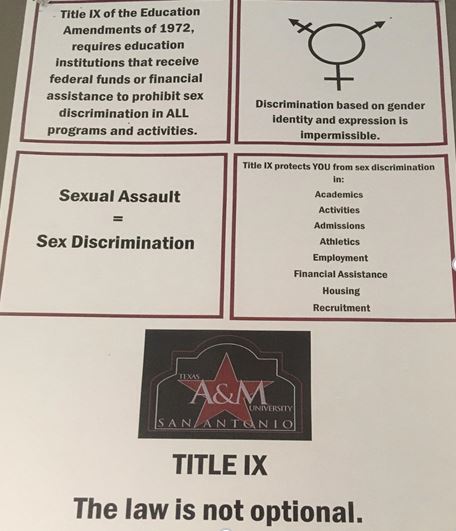

Even when gender identity and expression are mentioned in policy statements, they sometimes conflict with each other. At the time of data collection, A&M San Antonio’s nondiscrimination policy read as follows: “Texas A&M University-San Antonio does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, religion, national origin, age, disability, genetic information, veteran status, sexual orientation or gender identity in its programs and activities” (“Non-Discrimination/Sexual Harassment”). In contrast, the wording on the nondiscrimination posters on campus (see fig. 1) read as follows: “Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, requires education institutions that receive federal funds or financial assistance to prohibit sex discrimination in ALL programs and activities. Discrimination based on gender identity and expression is impermissible.”

Fig. 1. A nondiscrimination poster prominently displayed on campus. The poster states: “Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, requires education institutions that receive federal funds or financial assistance to prohibit sex discrimination in ALL programs and activities. Discrimination based on gender identity and expression is impermissible. Sexual assault = sex discrimination. Title IX protects YOU from sex discrimination in academics, activities, admission, athletics, employment, financial assistance, housing, and recruitment. Title IX: The law is not optional.” Photographed February 27, 2018.

These posters implied that gender identity and gender expression were both protected categories at A&M-SA under the precepts of Title IX at the time, per the statement “Discrimination based on gender identity and expression is impermissible.” Impermissible or not, the A&M system did not recognize gender expression as a protected category at the time. The phrasing of the nondiscrimination statement has since been updated, and now reads: “Texas A&M University-San Antonio does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, religion, national origin, age, disability, genetic information, veteran status, sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression in its programs and activities” (“Non-Discrimination/Sexual Harassment”). These are recent changes, reflecting a more coherent approach to diversity on campus, albeit one that is moving sluggishly and unevenly across departments. While the current administration is visibly supportive of the LGBTQ+ community, transgender individuals still have mixed experiences on campus: many instances of misgendering that I’ve experienced have come from faculty and staff rather than students. And, of course, Rainbow P.A.W.S. still doesn’t have a budget of its own.

To protect gender identity but not gender expression implies a contradiction: an institution might respect someone’s gender identity but might not grant them the right to express that identity safely on campus. For transgender individuals, gender expression is a complex issue: although legally changing your identity in the state of Texas is a surprisingly simple process, it also requires a good understanding of the court system and how to apply for financial waivers, and there is, as of yet, no option to legally identify as non-binary.[16] Because of this, the documents that we use to prove our identities are often inaccurate. Mismatches between gender expression and genders listed on official identity documents, including institutional items such as student and staff IDs, can be a matter of outright danger for transgender individuals. The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey found that, of Texas respondents, “32% of respondents who have shown an ID with a name or gender that did not match their gender presentation were verbally harassed, denied benefits or service, asked to leave, or assaulted” (3). When our institutions cannot even grant us the option to list our identities properly on our paperwork, we have to wonder how protected we actually are.

Being transgender on campus, being openly transgender on campus, is risky. The same 2015 report found that, of Texas respondents, “73% of those who were out or perceived as transgender at some point between K–12 experienced some form of mistreatment,” and “19% of respondents who were out or perceived as transgender in college or vocational school were verbally, physically, or sexually harassed because of being transgender” (1-2). More recently, in September 2021, the Trevor Project reported a 150% increase in crisis contacts from LGBTQ+ young people in Texas when compared to the same time period in 2020, with transgender and nonbinary youth in Texas “directly stat[ing] that they are feeling stressed, using self-harm, and considering suicide due to anti-LGBTQ laws being debated in their state” (Trevor News). Over seventy anti-LGBTQ+ bills were proposed by lawmakers in the 2021 Texas legislative session, more than forty of which specifically targeted transgender and nonbinary youth (Trevor News).

I only started using they/them pronouns publicly within the last few years, and while I’m comfortable introducing myself to my students that way now, the first time was nerve-wracking. They often misgender me anyway, largely because my gender expression is near-universally perceived as female, but many of them remember and do try. The same is true of my colleagues. But I am extremely fortunate: being misgendered, a type of microaggression, does not trigger gender dysphoria in me, the way it does for so many others. Gender dysphoria—that moment of awful affect—is often triggered because of issues with gender expression: moments when someone misgenders you, moments when for legal reasons you must take up an old identity that was never actually you, moments when you don’t feel safe enough to express your true identity, when the administrative systems of your institution do not allow for name changes, and when the paperwork for your institution does not allow you to identify as anything other than male or female.

The paperwork that binds me to my own institution, where my queer body does queer work, where it works to support other queer bodies—that paperwork is wrong. Matters are equally problematic for students: in spring 2021 I assisted in updating Banner and Blackboard to add a feature which would allow for preferred first names to be displayed,[17] but Banner only imports name changes to Blackboard when students register for classes. Students who update their names after registering for classes are confronted with their deadname every time that they log on to Blackboard, triggering dysphoria and often causing their fellow students to misname and misgender them in collective spaces such as discussion boards. Meanwhile, this system does not exist for faculty, so while I would prefer to alter my name and state my pronouns in Banner and Blackboard, I simply cannot. Since I only teach online nowadays, I am regularly misgendered by my students simply because they see the name “Sarah” every time I post anything to Blackboard and assume that I use feminine pronouns despite having they/them listed as my pronouns in both the syllabus and my email signature—more moments of uncomfortable affect, this time enabled by the mechanical processes of institutional policy.[18]

I feel safe at my institution, and I trust the gender identity and gender expression statements will protect me on my campus because I know the individuals that are tasked with enforcing those protections, and I trust them to act appropriately. I trust them to protect me, to protect my colleagues, and to protect my students. But not everyone is so lucky.[19]

These concerns are especially important given that on February 22, 2017, the Departments of Justice and Education withdrew landmark 2016 guidance explaining how schools must protect transgender students against discrimination under Title IX. Protections for transgender individuals were only reinstated three years later thanks to the Title VII Supreme Court decision, a ruling which itself makes no explicit statements regarding gender expression. It is especially concerning here in Texas, where the state legislature has been relentless in its attacks on the LGBTQ+ community, with more anti-LGBTQ+ bills filed in 2021 than in any other state, and where the most successful of these bills, where discriminatory legislation that bans transgender youth from participating in sports in alignment with their gender identity, was signed into law on October 25, 2021 by Governor Greg Abbot.

So how protected are we?

Conclusion: Words Are Not Enough

My experiences are not universal: they are intrinsic to my queer body and how it moves through space, through institutions, through the state in which I live and for which I work, affected by them and affecting them. My critique is affective in return—these statements might act as straightening devices, but I, in my queerness, can push back against them, affecting them just as they affect me: after all, the campus nondiscrimination statement appeared on our institutional website shortly after I noted its absence. My institution may have enfolded me into its body in an act of straightening, but, by doing so, it is also queered because of my presence within it. My queer body and my queer work have in turn served to queer my campus: Rainbow P.A.W.S. has hosted LGBTQ+ educational events, outreach programs, and resource fairs; the Preferred Name working group specifically recruited my assistance to help implement the preferred name system in Banner and Blackboard; and most recently, I have received an inquiry about joining another committee tasked with developing training materials for a new Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion certificate program.

I offer this critique while acknowledging that these documents are aspirational: used to determine the focus, purpose, goals, and commitments of an institution, the promises it makes to those who make up its body, and meaning very little in the absence of effective enforcement, of effective commitment on the part of our institutions. After my presentation on this topic at the 2018 Conference on College Composition and Communication, I spoke with someone who expressed intense frustration with his institution, where he was tasked with enforcing the campus nondiscrimination policy. Like so many others, he felt boxed in, surrounded on all sides by a “brick wall” of uninterested and unsupportive colleagues—the seemingly-universal experience of a diversity worker in higher education. I could offer him little more than sympathy and the hope that he might find like-minded others who would be willing to do the actual work of diversity with him. Perhaps now that the Supreme Court has ruled in our favor on Title VII, he will have better luck.

Institutions can also revise, review, and expand their nondiscrimination policies. While these statements do act as straightening devices, and likely always will simply due to their nature as legal documents, the expansion of such policies to include working definitions for commonly-used terminology, as well as more detailed definitions of discrimination—as one frequently sees in Title IX trainings—can help mitigate these effects and enable more effective enforcement of nondiscrimination policies. Thus, institutions should work to develop precise definitions for the following terms:

-

- Gender identity and discrimination: Institutions could borrow from their already-existing Title IX terminology and the examples used in institutional nondiscrimination training to identify and address instances of discrimination based on an individual’s gender identity.

- Gender expression: In addition to developing a clear definition for what gender expression is and how it differs from gender identity, institutions could provide specific examples of what discrimination based on gender expression might look like by developing further examples to be added to their already-existing Title IX training.

- Sexual orientation and discrimination: While most institutional trainings do cover sexual orientation in their Title IX training, albeit generally briefly, the development of further examples of discrimination based on sexual orientation could provide more specific guidance for the enforcement of such policies.

The working definitions and examples for these terms should be linked directly from the policy statement on the institution’s website. They should also be available internally, and the definitions and examples added to each institution’s Title IX training program. Policy and subject matter experts should be called upon to further develop these statements, working definitions, and examples. In larger systems, such developments should take place at the system level, rather than at individual institutions, to ensure consistency across all campuses.

Revising these statements, developing working definitions, and providing further examples and training is a starting point, but we cannot let that become the only point, nor can diversity documents be our only concern. They affect us, but attending to such documents is not enough. They are important because of their ability to determine how, when, and why our institutions protect or fail to protect us, but their power lies in engagement and enforcement, in being regularly updated to reflect the ever-changing legal and political climate in Texas and the country. As employees of these institutions, it is our duty to raise questions about them, to critique them, and revise them, but also to recognize the limitations of this work. It is not and will never be enough to speak about diversity: we must take action, beyond the bare minimum that the law requires, to create safer spaces on campus for everyone.

This last point is both the most nebulous and most important one: cultivating an inclusive campus environment, one that provides visible and meaningful support for the LGBTQ+ community, is the most effective way to create change. Creating institutional policies and documents that can better protect our students and ourselves begins with education, outreach, and understanding. A committee tasked with policy revisions is better equipped to make changes that support the LGBTQ+ community when they are trained in LGBTQ+ issues and understand the challenges that may be faced by their students, particularly given the specific cultural and geographic contexts of individual institutions. An awareness of state and local challenges to LGBTQ+ rights is essential for shaping policies that can better protect our students, staff, and faculty. Visible and concrete dedication to supporting the LGBTQ+ community is essential here in Texas, where the transgender youth sports ban has gone into effect as of January 18, 2022, and school boards across the state are facing an unprecedented number of requests from politicians and parents to remove books dealing with race, sexuality, and gender from school libraries after a parent complaint about Maia Kobabe’s memoir Gender Queer went viral (Hixenbuagh).

On campus, it is easy to forget that the policy documents that we create, cloistered away in committees and tucked away on some forgotten webpage, are affective objects—they shape how we work and how our institutions work. They are living documents that people turn to when they are trying to make decisions about where to go and what to do. Creating them once is not enough: they must be attended to, revised, and updated to reflect the changing circumstances of our students, our politics, and the world.

We are never “done” with diversity. We are never “done” with providing what protections we can for those who are marginalized within our institutions and within the academy as a whole. But we can and should do better: our students’ safety—our safety—depends on it.

Footnotes

[1]As of this writing (February 14, 2022) there are still no statewide nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ+ individuals in Texas.

[2]Shortly after my exchange with the department chair, a link to the institutional nondiscrimination statement appeared on the university’s homepage. It seems as though by asking about the lack of nondiscrimination statement I may have successfully (albeit unintentionally) engaged with Porter et al.’s activist methodology of institutional critique (610-642), a practice which I continue in limited form in this article.

[3]Working closet: “complicated, layered, and unorthodox space comprising a set of networked relations and interactions (including rhetorical practices and strategies) between the LGBT individual and all life contacts,” focused particularly on “workplace and professional contacts and interactions” (Cox 3-4).

[4]See Toward a New Rhetoric of Difference, the edited collection Negotiating Disability: Disclosure and Higher Education, and Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability.

[5]For another experience of affect alienation, this time with Safe Space stickers, see Fox, 496-511.

[6]Folx: an alternative spelling of “folks” used most commonly on social media platforms by members of the LGBTQ+ community, but referring to all people, particularly members of marginalized communities.

[7]See Fox, 496-511.

[8]DFAB: Designated Female At Birth. A term commonly used in the trans* community to refer to the gender identification granted to infants on legal documents such as birth certificates. The corresponding term is DMAB, Designated Male At Birth.

[9]I declined to do so.

[10]Inspiration porn: a term coined by Stella Young to describe the portrayal of disabled people as inspirational solely on the basis of their disability.

[11]Homonormativity: a term popularized by Lisa Duggan to describe a politics that upholds assimilationist and heteronormative ideals within the LGBTQ+ community, including a focus on marriage, monogamy, and childrearing.

[12]Amatonormativity: a term coined by Elizabeth Brake to describe social ideals and pressures about romance, including a focus on monogamy and marriage. Allonormativity: a term coined within the asexual community to describe social ideals and pressures about sexual attraction, mainly that all people experience it.

[13]For a relevant overview of the process through which a gender identity and expression statement was added to the University of Houston-Clear Lake’s nondiscrimination statement, see Case et al.

[14]Intersex: An umbrella term used for the “estimated one in 2,000 babies…born with reproductive or sexual anatomy and/or a chromosome pattern that doesn’t seem to fit typical binary definitions of male or female. These traits…include androgen insensitivity syndrome, some forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Klinefelter’s syndrome, Turner’s syndrome, hypospadias, Swyers’ syndrome, and many others” (InterACT).

[15]Trans*: a term used as a form of shorthand within the LGBTQ+ community to refer to a diverse array of non-cisgender identities, including non-binary and culturally-specific identities.

[16]Very few of our students are aware of how to navigate the process of changing their legal name and gender identity in the state of Texas, assuming that they are in a position to safely do so. Many are not.

[17]This was the term used by the group, though the use of the term “preferred” is contentious, and is generally no longer considered acceptable when it precedes pronouns. The group nonetheless used the term “preferred” for names, as the policy and technology change applied not only to trans* individuals, but also those who wished to change the names they had on file with the university for reasons unrelated to gender. Students can also indicate their pronouns in this system, although that information is kept confidential and can only be accessed by instructors through Banner.

[18]While Blackboard does allow users to edit their personal (first) name, this function is enabled by the institution rather than the user, and TAMUSA does not currently allow such edits.

[19]To the surprise of exactly no one, concerns with the enforcement of trans-inclusive nondiscrimination policies in higher education have been a consistent concern for trans* folx over the years—see Seelman and Goldberg et al.

Works Cited

“2015 U.S. Transgender Survey: Texas State Report.” National Center for Transgender Equality, 2017, www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTSTXStateReport%281017%29.pdf. Accessed 24 Aug. 2020.

Ahmed, Sara. “Happy Objects.” The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory Seigworth, Duke UP, 2010, pp. 29-51.

—. Living a Feminist Life. Durham and London, Duke UP, 2017.

—. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Duke UP, 2012.

—. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Duke UP, 2006.

Carrol-Miranda, Moira. “Access to Higher Education Mediated by Acts of Self-Disclosure: ‘It’s a Hassle.’” Negotiating Disability: Disclosure and Higher Education, edited by Stephanie Kerschbaum, Laura Eisenman, James Jones, David Mitchell, and Sharon Snyder, U of Michigan P, 2017, pp. 275-90.

Case, Kim, et al. “Transgender Inclusion in University Nondiscrimination Statements: Challenging Gender-Conforming Privilege through Student Activism.” Journal of Social Issues, vol. 68, no. 1, 2012, pp. 145-61.

Cox, Matthew. “Working Closets: Mapping Queer Professional Discourses and Why Professional Communication Studies Need Queer Rhetorics.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 1-25, doi:10.1177/1050651918798691. Accessed 24 Nov. 2021.

Ferguson, Roderick. The Reorder of Things: The University and Its Pedagogies of Minority Difference. U of Minnesota P, 2012.

Fox, Catherine. “From Transaction to Transformation: (En)Countering White Heteronormativity in “Safe Spaces”. College English, vol. 69, no. 5, 2007, pp. 496-511. JSTOR, www.jstor.com/stable/25472232. Accessed 24 Aug. 2020.

Goldberg, Abbie, et al. “What is Needed, What Is Valued: Trans Students’ Perspectives on Trans-Inclusive Policies and Practices in Higher Education.” Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, vol. 29, no. 1, 2019, pp. 27-67.

Gregg, Melissa, and Gregory Seigworth, editors. “An Inventory of Shimmers.” The Affect Theory Reader, Duke UP, 2010, pp. 1-25.

“H.B. No. 2504.” Texas Legislature Online, 2009, capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/81R/billtext/html/HB02504F.htm. Accessed 24 Aug. 2020.

Hixenbaugh, Mike. “Banned: Books on Race and Sexuality are Disappearing from Texas Schools in Record Numbers.” NBC News, 1 Feb. 2022, www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/texas-books-race-sexuality-schools-rcna13886. Accessed 4 Feb. 2022.

The Human Rights Campaign Foundation. “2021 State Equality Index.” Human Rights Campaign, 2021, https://reports.hrc.org/2021-state-equality-index-2. Accessed 4 Feb. 2022.

InterACT. “interACT FAQ.” InterACT: Advocates for Intersex Youth, 2016, interactadvocates.org/faq/. Accessed 4 Feb. 2022.

Iverson, Susan. “Constructing Outsiders: The Discursive Framing of Access in University Diversity Policies.” The Review of Higher Education, vol. 35 no. 2, 2012, pp. 149-77, doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2012.0013. Accessed 18 Nov. 2019.

Kerschbaum, Stephanie. Toward a New Rhetoric of Difference. CCCC/NCTE, 2014.

Mallory, Christy, et al. “The Impact of Stigma and Discrimination against LGBT People in Texas.” The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law, 2017, williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/docs/peitho/files/Texas-Impact-of-Stigma-and-Discrimination-Report-April-2017.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2020.

Mayr, Andrea. Language and Power: An Introduction to Institutional Discourse. Continuum, 2008.

McRuer, Robert. Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability. New York UP, 2006.

Morrish, Liz, and Kathleen O’Mara. “Queering the Discourse of Diversity.” Journal of Homosexuality, vol. 58 no. 6-7, 2011, pp. 974-91, doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.581966. Accessed 18 Nov. 2019.

“Non-Discrimination/Sexual Harassment.” Texas A&M University – San Antonio, 2017, 2021, www.tamusa.edu/humanresources/eeo.html. Accessed 18 Nov. 2019; 24 Nov. 2021.

Office of Institutional Research. “Texas A&M University – San Antonio Fact Book 2016.” Texas A&M University – San Antonio, 2016, https://www.tamusa.edu/office-information-research/assets/Texas-AM-University-San-Antonio-Fact-Book-Fall-2016.pdf. Accessed 24 Nov. 2021.

Porter, James, et al. “Institutional Critique: A Rhetorical Methodology for Change.” CCC, vol. 51, no. 4, 2000, pp. 610-42, JSTOR, www.jstor.com/stable/358914. Accessed 24 Aug. 2020.

Sears, Brad, et al. “LGBT People’s Experiences of Workplace Discrimination and Harassment.” The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law, 2021, williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/docs/peitho/files/Workplace-Discrimination-Sep-2021.pdf. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022.

Seelman, Kristie. “Recommendations of Transgender Students, Staff, and Faculty in the USA for Improving College Campuses.” Gender and Education, vol. 26, no. 6, 2014, pp 618-35, doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2014.935300. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022.

“System Regulation 08.01.01, Civil Rights Compliance.” The Texas A&M University System, 2021, policies.tamus.edu/08-01-01.pdf. Accessed 24 Nov. 2021.

“Texas Higher Ed Enrollments.” Excel file, Texas Higher Education Data, 2019, www.thecb.state.tx.us/reports/DocFetch.cfm?DocID=12815&Format=XLS. Accessed 6 June 2020.

“Title IX.” Texas Tech University, 2019, www.depts.ttu.edu/titleix/. Accessed 6 June 2020.

“Title IX and Sex Discrimination.” U.S. Department of Education, 2015, www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/tix_dis.html. Accessed 6 June 2020.

“Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, www.eeoc.gov/laws/statutes/titlevii.cfm. Accessed 29 June 2020.

Trevor News. “New Data Illuminates Mental Health Concerns Among Texas’ Transgender Youth Amid Record Number of Anti-Trans Bills.” The Trevor Project, 27 Sep. 2021, www.thetrevorproject.org/blog/new-data-illuminates-mental-health-concerns-among-texas-transgender-youth-amid-record-number-of-anti-trans-bills/. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022.

University Communications. “Texas A&M University-San Antonio’s HSI Designation Benefits Students and Surrounding Community.” Texas A&M University – San Antonio, 2017, www.tamusa.edu/news/2017/03/hsi-designation.html. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022.

Urciuoli, Bonnie. “Neoliberal Education: Preparing the Student for the New Workplace.” Ethnographies of Neoliberalism, edited by C.J. Greenhouse, U of Pennsylvania P, 2010, pp. 162-76.

Woodford, Michael, Jessica Joslin, and Kristen A. Renn. “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Students on Campus: Fostering Inclusion Through Research, Policy, and Practice.” Transforming Understandings of Diversity in Higher Education: Demography, Democracy, & Discourse, edited by Penny Pasque, Noe Ortega, John Burkhardt, and Marie Ting, Stylus Publishing, 2016, pp. 57-80.