|

CompPanels: Images from the Annals of Composition #40 Acrostic: Subtext and Countertext |

| Imagine you are George Tenet, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency. It is a few days after your interview with NBC's Scott Pelley on 60 Minutes (April 29, 2007), during which you insisted three times, "We do not torture." Now in your mailbox is a fan letter in the form of a poem. The poem is a sonnet, and the first quatrain goes:

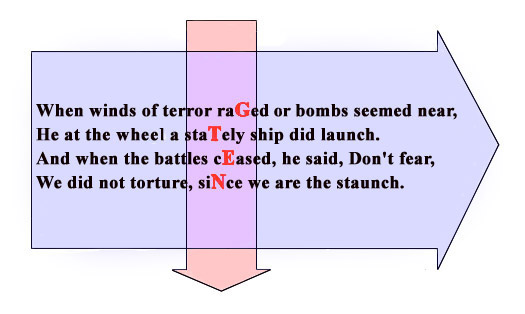

This is gratifying, since you are George Tenet and not a connoisseur of poetry, but since you are George Tenet and ex-director of the CIA, you run the sonnet through computer cryptography software designed to search text for hidden messages. With no hesitation the software reports back that there is indeed a coded message. Isolating the central letter of each line (disregarding spaces and punctuation) and moving from the first to the fourteenth line (this is a sonnet, remember), the poem spells out G-T-E-N-E-T-T-O-R-T-U-R-E-R. The poem is an acrostic. More exactly it is a kind of acrostic called a mesostich (or mesostic), which forms words out of the middle letter of lines. Since in English the subtext of an acrostic runs downward in contrast to the text which runs rightward, part of the effect is graphic.

Contradictory eyepaths, I argue, suggest the presence of contradictory texts.1 In a word, the acrostic subtext may be a countertext. No doubt this is not always the case. In Ben Jonson's "Argument," a poem that initiates his 1606 play Volpone, or, the Fox, the first letters of the seven lines simply read V-O-L-P-O-N-E. But like spy code hidden in a love letter, countertext is to be expected in most acrostics. In our hypothetical example, the text says Tenet does not condone torture; the acrostic subtext says he does. Countertext provides the plot for the history of many actual, non-hypothetical acrostics. The speaker of John Peale Bishop's lovely sonnet, "A Recollection," remembers a Renaissance painting of a Venetian woman, "red hair / Unbound and bronzed by sea-reflections, caught / Crinkled with sea-pearls." The last three lines express a tribute to fine art.

Speak of "loveliness" and "courtesies"! The first letters of this sonnet's fourteen lines spell F-U-C-K-Y-O-U-H-A-L-F-A-S-S. I learned this from Theodore Roethke, in class. He first read aloud the poem (he was a fabulous reader of poetry), then explained the acrostic, then, laughing immoderately, told the story that Oscar Williams had naively selected "A Recollection" for one of his poetry anthologies—perhaps A Little Treasury of American Poetry—and had to recall the first printing to remove the poem. Roethke's story may be apocryphal.2 Scholars have well documented the long history of acrostic poetry, which extends back to classic Greek poetry. But acrostic prose is less studied, perhaps because it is less obvious. In Rationale of the Dirty Joke (Second Series, 1975), Gershon Legman recounts, second hand, the story that an offering of house commodes in a 19th-century Sears Roebuck catalog was titled "Sears' Handy Indoor Toilets," for which the copy editor was fired. In January of 2001, when the London Daily Express acquired a new owner, Richard Desmond, the paper pubished an article about organic farming, the first letters of sentences spelling F-U-C-K-O-F-F-D-E-S-M-O-N-D. This week (I am writing Oct. 28, 2009) an astonishing example appeared at the highest level of California politics. Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed a Senate bill that would have helped the port of San Francisco with its financies, and in doing so sent the following letter to members of the Senate. The acrostic, beginning with the first letter of the first sentence, is not hard to detect. I am returning Assembly Bill 1176 without my signature. For some time now I have lamented the fact that major

issues are overlooked while many Do you know of other instances of acrostic messages hidden in public prose? Send them to me. With your permission, I'll add them to this page. Footnotes 1. For eyepaths, see CompPanel 38). 2. Bishop's sonnet "A Recollection" can be found in his Collected Poems (Scribners, 1948), pp. 71-72; copies are easily found on the internet. By the way, "Barberini bees" in the last line refers to the heraldic emblem of the 17th-century Barberini family in Rome, great patrons of the arts. Sometimes artists would incorporate three bees into their painting to acknowledge the patronage. Note that the speaker of the poem is silent just as the painted bees are and just as the subtextual acrostic message is. (Is "bees" a pun on the letter B?) And just as the poem's acrostic subtext goes at cross-purposes with its surface text, a painter might have painted in the Barberini bees for "courtesy" although he disagreed with his patron's demands for subject matter and style. Bishop scholars point out that "A Recollection" first appears in the manuscript of a coming-of-age novel that Bishop started but never finished in the 1920s and therefore reflects the psychology of the main character who composes the poem. But that doesn't explain why Bishop later included it, silently, in his collected poems.) 3. Detected by Tim Redmond of the San Francisco Bay Guardian Online. Thanks to Glenn Blalock who drew this to my attention. RH, May 2007/October 2009 |