CHAPTER FIFTEEN

The Role of New Media Expertise

in Shaping Writing Consultations

HOW WE TEACH WRITING TUTORS

Jessica Clements

Whitworth University

It is easy to say that digital technologies are changing contemporary communication. It is less easy to say how writing center practitioners should address this change. To answer the latter, I replicated Sue Dinitz and Susanmarie Harrington's study "The Role of Disciplinary Expertise in Shaping Writing Tutorials"—to better understand how a tutor's new media expertise might affect a writing tutorial's overall effectiveness and what implications that might hold for how we best educate our tutors to address technology-rich writing assignments. My research in teaching tutors to address technology-rich assignments suggests that tutors' confidence may impact effectiveness more than their expertise with new media; therefore, this chapter includes practical suggestions for building new media composing confidence in existing tutor education programs.

Context: Writing Centers and "New Media" Expertise

Global Response

"New media" can be understood in a variety of ways but largely comprises textual production that transcends traditional word-based, print-based writing forms. When we think of new media, we often think of composing projects that use digital technologies, but new media texts do not have to be digital. Rather, multimodal texts—texts that utilize some combination of linguistic, visual, aural, gestural, and spatial modes of communication (words, photos, color, layout, etc.)—comprise the essence of new media composition. In other words, new media can be defined as interactive forms of communication technologies (Ball et al. 4; Lee and Carpenter xviii).

Writing centers have tended to respond to new media in one of three ways (Lee and Carpenter xix):

- Hire tutors with little to no preexisting new media-specific knowledge. One can see the virtue in requiring tutors to have no new media-specific writing tutoring knowledge at the time of hiring. Most writing centers already carry the weight of helping writers across a plethora of disciplines and academic ranks. As writing center professionals, we may be reticent to add another dimension of assistance if we are uncertain of our own expertise in that regard; Jackie Grutsch McKinney suggests some of us circulate a skeptical inner dialogue: "we are not sure that we can do a good job of tutoring new media, so perhaps we shouldn't try" (255). There is valid concern that further straining the scope of generalist tutor expertise—particularly when writing center directors may feel underprepared to facilitate new-media specific tutor education—will create more problems than solutions.

- Require tutors to have a working knowledge of new media composition. Many writing center practitioners (including Grutsch McKinney 255), also see the virtue of a middle ground: requiring a working knowledge of new media composition. If writing tutors are already trained to privilege interrogation of the rhetorical principles underlying a piece of writing, then why can't that knowledge be extended to improve new media compositions as well? The relationships between rhetor, subject, and audience may be extended, expanded, and complicated by different/multiple modes, but minimal, targeted education in basic design principles, for example, could equip tutors with the language needed to respond to this type of text productively: "We don't need to be, say, filmmakers to respond to video in new media composition. However, we do need to be able, at a minimum, to respond to how the video relates to the whole of the text" (Grutsch McKinney 251).

- Require tutors to possess (or to acquire) expertise in new media technology and software. Finally, requiring tutors to possess expertise in new media technology and software situates those tutors' identities somewhere between information technology professionals and multimedia writing pedagogy experts. We must be careful not to conflate "expertise" with "mastery," and we must note that this expertise is often practically enacted by a handful of specialist tutors within larger generalist organizations—much like Writing in the Disciplines tutors exist to facilitate writing tutoring through a lens of disciplinary familiarity within larger programmatic writing cultures. Unfortunately, many tutors correlate tutoring new media compositions with said mastery, with the ability, for example, to navigate Adobe InDesign's seemingly endless menus without reference (see Figure 1) or to analyze a visually rich project with the vocabulary of a seasoned graphic designer. While those proficiencies might afford a high level of confidence on the part of the tutor, one can see how sustaining such an intense level of confidence-inducing education for an entire writing center staff would not be practically feasible.

|

| Figure 1. The many tools and menus of Adobe InDesign's user interface. Original screen capture by author. |

Local Practice

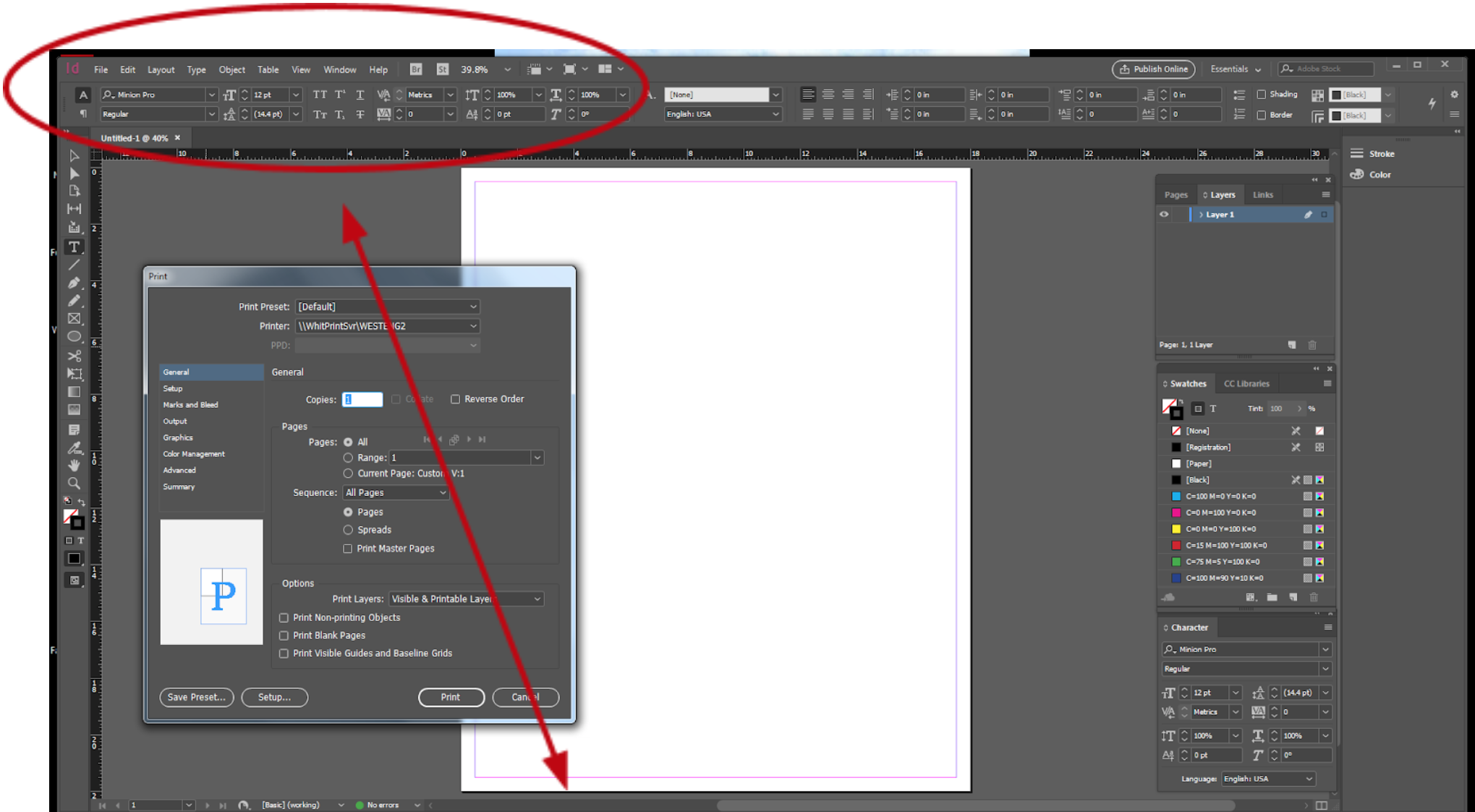

I educate my small liberal arts college (primarily undergraduate) tutors by targeting the middle ground: cultivating a working knowledge of new media composition. Tutors apply and are interviewed in the fall. Selected tutors are invited to take a mandatory writing center theory and practice preparation course in the spring. In the preparation course, I require prospective tutors to complete a "Visual Rhetoric in Practice" assignment that I modified from Tammy Conard-Salvo. This assignment asks them to "support an argument through advertising" or, in other words, to craft a message primarily through visual means. To ground the assignment, I invite them to use our center's mission (see Figure 2) as the subject of their ad. I also ask them to complete a three- to four-page word-based reflection to explain how meaning was built in their visual message. We study contrast, repetition, alignment, and proximity (C.R.A.P), color theory, and the essentials of typography, and I introduce Adobe InDesign as a composing option. We spend significant time locating resources and discussing strategies for troubleshooting new media composing challenges. I introduce the Visual Rhetoric in Practice assignment in Week 6, and final drafts are due in Week 11. I dedicate approximately two to three weeks of class time to direct instruction for this assignment and allow ample time for drafting and revising (meaningful tinkering and play) outside of class.

|

| Figure 2. Whitworth Composition Commons (WCC) mission statement poster. Created by and reproduced with permission from Kalani Padilla. |

Students have been both creative and critical in the work they produce for this assignment and excel at identifying individual rhetorical choices at work in their compositions—but is that enough? Is this foundational journey into the basic principles of visual rhetoric enough to afford tutors sufficient expertise to help writers with the variety of multimodal projects that might cross their tutoring tables?

Study Design

In order to test the efficacy of my new media tutor education approach, I replicated the methods of Dinitz and Harrington's study "The Role of Disciplinary Expertise in Shaping Writing Tutorials," one of the first empirical inquiries into the generalist versus specialist tutor debate. Replicating their methods proved an apropos fit for my study given our shared goals of close and objective analysis of "how tutor expertise actually affects tutoring sessions" (74). Dinitz and Harrington studied taped tutorials from history and political science classes, subsequently coding the transcripts for session structure and tutoring moves. They also asked disciplinary faculty members to offer their understanding of how the tutor's disciplinary expertise may have affected the success of the tutorial. Four of the seven tutors involved had disciplinary expertise, "evidenced by the successful completion of multiple courses in the discipline" (77-78). From their triangulated analysis, Dinitz and Harrington claim that disciplinary expertise

- affords more accurate assessment of writers' papers and remarks,

- allows for more appropriate agenda-setting,

- permits tutors to ask questions that lead to writers identifying/addressing key issues,

- encourages tutors to extend discussions,

- bolsters tutors' confidence in iteratively returning to important global issues and calling out writer misunderstandings, and

- empowers tutors to make already knowledgeable writers even stronger writers. (92-93)

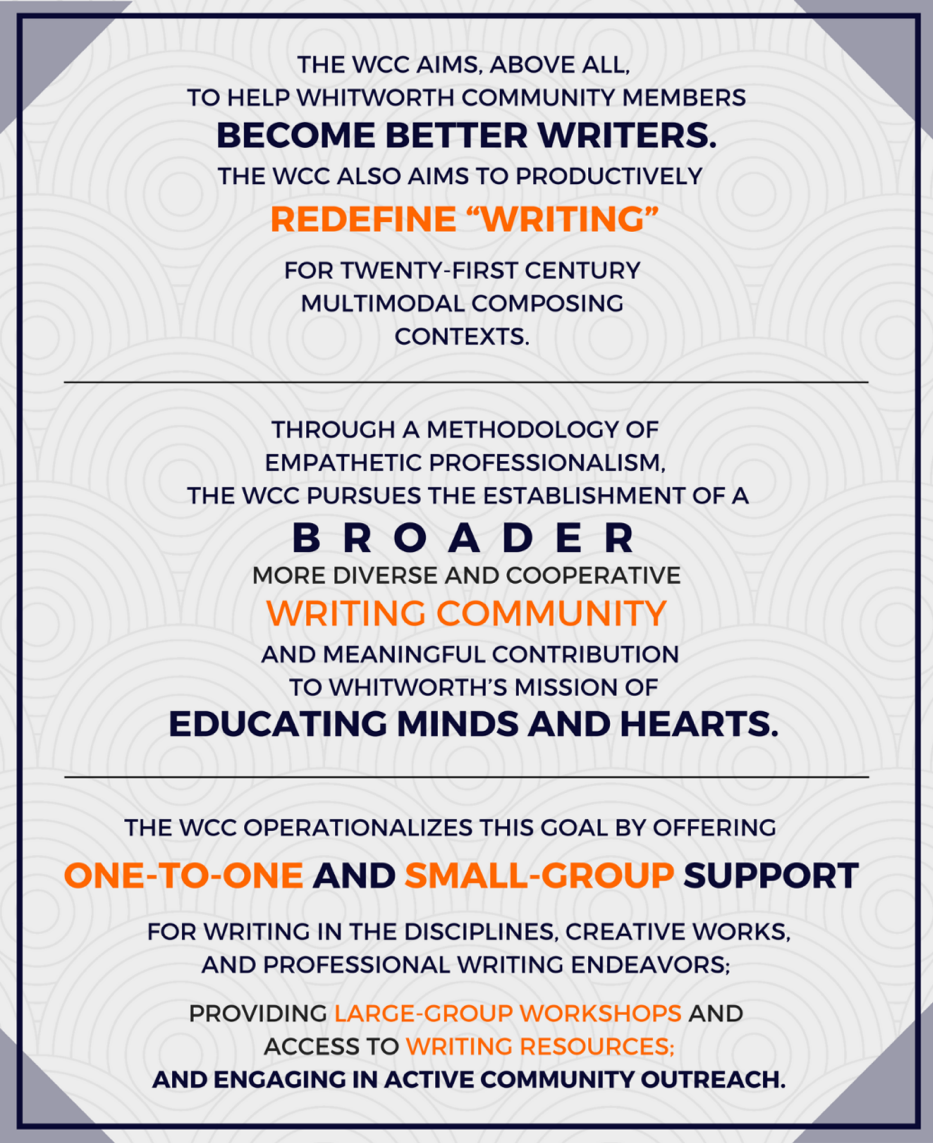

Replicating Dinitz and Harrington's methods for assessing tutoring expertise, my study comprises tapes and transcripts of tutorial sessions (see Figure 3). With IRB and tutors' and writers' approval, I video recorded writing center sessions involving multimodal project consultation (defined as any project transcending traditional word-based, print-based media) in Spring 2016, ultimately garnering fifteen willing participant pairs of tutors and writers. Given that all involved tutors were exposed to the same new media education materials in the writing center preparation course, I assumed that each tutor had at least a working knowledge of new media composition. It is worth noting, however, that tutors at my university come from a variety of disciplines, some of which include coursework that could contribute to a higher level of new media expertise.

|

Figure 3. Methods map for research study of tutor expertise in new media. Original infographic by author. |

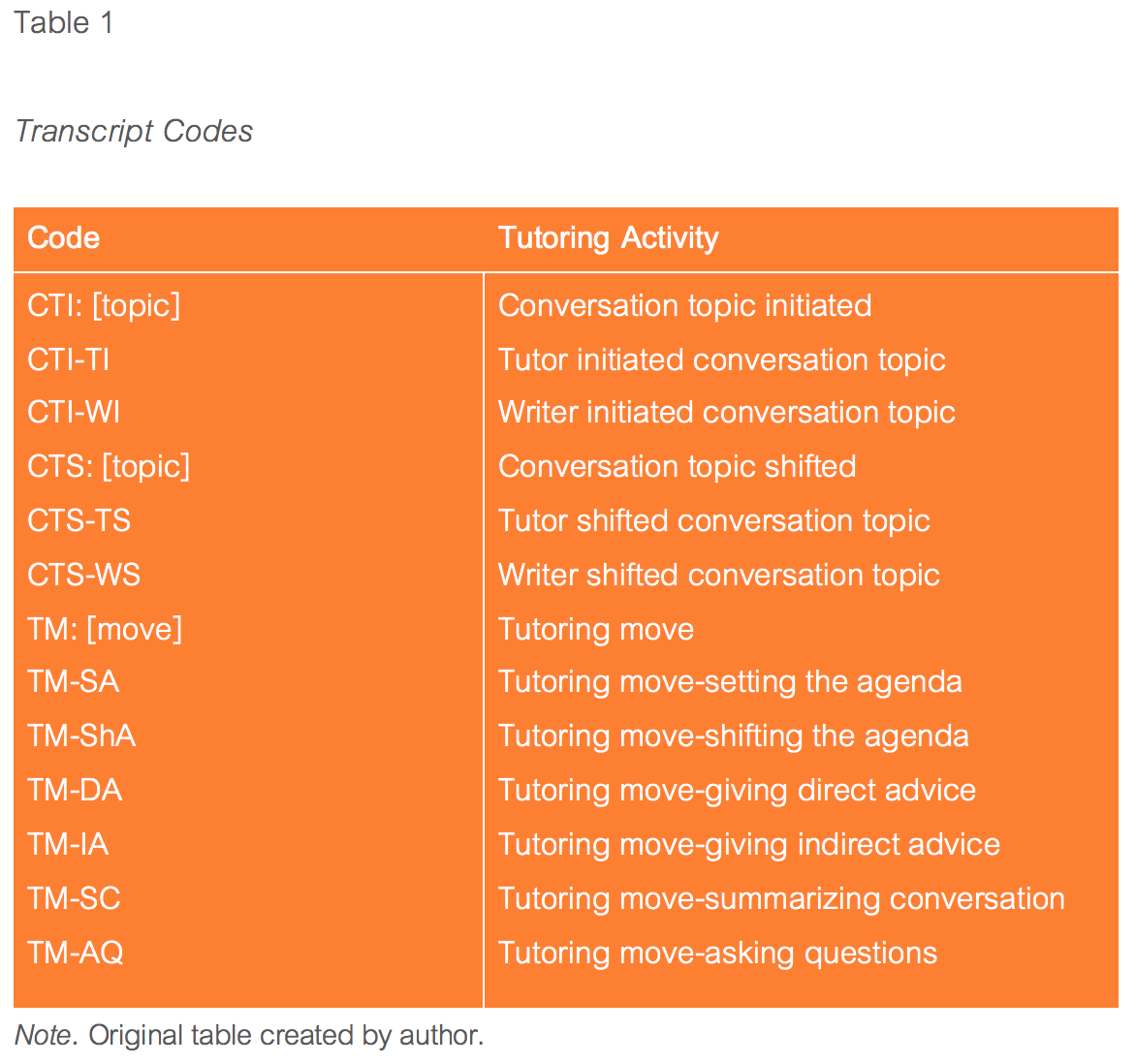

Videos were transcribed, and each transcript was coded. In accordance with Dinitz and Harrington's methods, I coded each transcript by conversation topic, shifts in those topics, and the parties responsible for initiating and shifting those topics. I also coded each transcript by tutoring moves, reflecting the types and kinds of tutoring moves made by individual tutors in individual sessions: setting/shifting the agenda, giving indirect or direct advice, summarizing conversation, and asking questions to move the consultation forward (see Table 1). Identifying conversation topics and tutoring moves allowed me to determine session structure, conversation initiation patterns, and types of tutoring moves in context.

I then noted if, where, and how these tutoring activity patterns overlapped with new media expertise (primarily, did the tutor evidence knowledge of generic expectations and available composing choices for the multimodal project at hand?). To understand the role of new media expertise in shaping writing consultations, I considered whether each session was effective, overall, in "its likelihood in resulting in successful revision" (Dinitz and Harrington 79). An effective session was characterized by a tutor's ability to address global issues, to evaluate and—when necessary—challenge a writer's point of view, to ask questions to productively extend conversation, and to afford general lessons for the writer's development (85).

Results: Having Confidence Matters

Three patterns emerged from the videotaped and transcribed new media tutorials.

First, each tutorial presented a strikingly similar session structure—similar to one another and similar to what one might expect of a monomodal (traditional word-based, print-based) text tutoring session: agenda-setting and early session consulting focused on global issues, mid-session consulting focused on investment in more specific local issues, and end-of-session consulting that revisited global issues. Some sessions were more productively iterative than others, but tutors were clearly confident in opening sessions focused on global issues. That is, tutors asked adept questions about audience, purpose, and context when situating the work that needed to be done on their writers' new media compositions, primarily comprising whether the chosen media was appropriate for the communicative task at hand. The following transcript (Figure 4) illustrates a tutor assisting a writer in composing a visual representation of an argumentative essay on climate change for a first-year composition course. The tutor might have been tempted to immediately devolve into discussing the particular, local issues of crafting a visual poster in PowerPoint versus Prezi, especially at the writer's insistence that a "poster would be easy"; however, to the writer's surprise ("Uh . . .") the tutor guides the writer to first and foremost consider the purpose of the composition with repeated global-level questions: "What . . . would you like to communicate with this? . . . What was the argument of your research?"

Writer: Yeah, I just need to think of ideas and, like, maybe ways to do that—I don't know.

Tutor: Ok, so, is it, like, a—are you wanting to do a visual poster or . . . ?

Writer: Yeah, I think a poster would be easy, and I kind of want to use PowerPoint, and she said we could use PowerPoint or, like, Prezi or something.

Tutor: Ok, cool. So what, kinda, would you like to communicate with this?

Writer: Uh . . .

Tutor: What was the argument of your research?

Figure 4. New media tutoring session transcript #1. Tutors opened multimodal composing consultations with confidence, focusing on global issues such as purpose.

Second, in discussing local issues—such as particular font or color choices—most tutors were able to articulate the effectiveness of local media-specific choices related to audience and purpose. A few tutors devolved into less-than-productive like/dislike responses, which often tell us more about the unique and sometimes quirky predilections of an individual reader and less about the rhetorical response the author will likely garner from the target audience. By and large, though, this problematic response was performed less prevalently than tutors recalling and applying productive multimodal composing language, such as discussing the basic design principle of alignment and how alignment choices would impact what the author wants to "tell" their audience (as in the following transcript; see Figure 5). Surprisingly, those same tutors opted to subsequently undercut their authority with phrases like "I'm not an expert in design . . . ."

While it can be a helpful for a tutor to qualify their response "as a reader" (suggesting there are other viable composing choices available and that the author is ultimately responsible for making that choice), leaving a statement such as "I'm not an expert in design" without qualification—without pointing the writer to additional resources that could confirm or challenge the tutor's reading—might leave the writer questioning the effectiveness of the advice that was already offered. This type of move is likely to undercut the success of the tutor's evaluation and, when necessary, credibility in challenging writers' points of view.

The following transcript (Figure 5) illustrates three distinct moments in a thirty-minute multimodal text tutorial in which the tutor enacts this undercutting of authority. The tutor is guiding the writer's choices in a visual representation assignment (the writer had written a rhetorical analysis of music videos and their objectification of men and women). The writer seeks specific guidance for incorporating a limited number of photo-visual elements for the greatest impact in this first-year composition presentation assignment. The tutor uses hedges such as "probably" on multiple occasions, initiates third-party opinion, directly claims "not [to be] an expert in design," and suggests they are "at a loss to tell you more" because they are comparing themselves to "friends who . . . know everything about fonts." These moves, collectively, likely influenced the writer's choice to go with "safe" and "standard" choices, which, I argue, do not necessarily correlate with optimally effective multimodal composing choices rhetorically tailored to individual composing contexts.

Tutor: Yeah, in terms of how much skin is actually showing. I think this one does have more shock value than some of the other ones, probably, and I would tend to say it's probably an okay level for this sort of presentation. We could also get a third opinion if you like?

Writer: Totally, yeah.

Writer: I could change the color of the words. I think a white outline would be better.

Tutor: Yeah. Yeah, I think that's—

Writer: Helps a little.

Tutor: Much easier to read. What do you think about—you were playing again with these—so you've got some weight on this side, putting some weight on these and a little bit back up in the top-like, what did it look like when you had it all left aligned?

Writer: Not balanced, is it?

Tutor: Mmm, maybe. I'm not an expert in design so—yeah [both laugh].

Tutor: Rethink font, yeah. It can be pretty simple, even, I think. Look, now you've got the thick lettering that's—yeah.

Writer: Mmm-hmm.

Tutor: Mmm-hmm. And at this point I am at a loss to tell you more about that. I have friends who, like, know everything about fonts—like, "here's the field and this and this and that"—but you're probably safe.

Writer: I'll use Times New Roman or something—professional.

Tutor: That's standard, yeah. I think font can do more, but that's not gonna, like, go wrong.

Figure 5. New media tutoring session transcript #2. Tutor offered effective advice regarding local media-specific composing choices but belied confidence by consistently hedging that advice.

Third, when writers offered a working knowledge of new media composing, tutors felt confident in extending the writer's knowledge with their own working knowledge; however, only tutors with more "expert" knowledge of new media composing (or at least more regular practice) were able to project a confidence in working with writers new to new media composition.

I determined sessions as more successful, then, when (A) the writer already had strong ideas regarding the nature of what they wanted to compose, in what media, and through which software, and/or (B) when the tutor expressed additional confidence garnered through regular engagement with multimodal projects and software outside of tutor education and regularly scheduled tutoring hours, a confidence they may or may not have garnered through their disciplinary coursework. The following transcript (Figure 6) illustrates a revelatory exchange concerning such preexisting confidence.

Tutor 1, a computer science major, was assigned to consult with the writer, a French major; however, Tutor 2, an English literature major, was also working in the writing center without a scheduled appointment. When the writer reveals they have been assigned to compose a "professional poster" for an upper-division philosophy course (a task for which they claim to possess little working knowledge despite having read parts of the Non-Designer's Design Book for a "TED Talk class"), Tutor 1 admits a similar lack of working knowledge of this particular multimodal genre and invites Tutor 2 into the consultation. Tutor 2 suggests she was ". . . also recently challenged to kind of make a more humanities thing into a poster," and she ". . . can affirm that it can be done, and it can be done effectively." In this case, Tutor 2's recent critical engagement with poster-making allowed her to ask questions to productively extend conversation (writer changes perspective of "no" knowledge to "basic" knowledge) and afford general lessons for the writer's development as a writer (tutor suggests starting with examples, interrogating "industry standard[s]," considering the flexibility of genres, etc.).

Tutor 2: So that's good. What else do you know about posters, academic posters, business posters?

Writer: I literally know nothing.

Tutor 2: Nothing?

Tutor 1: . . . do you know anything about general graphic design principles? That would probably be a good place to start.

Writer: I know a few things. We read for our TED Talk class the Non-Designer's Design Book.

Tutor 2: Mmm-hmm.

Tutor 1: Okay.

Writer: So I know, like, those kinds of things.

Tutor 2: Yeah, which is a really good start.

Writer: Yeah, which is a really basic overview.

Tutor 2: I think it also may be helpful to look over a few examples and see what the examples are doing effectively and ineffectively. Um, a research poster does have some kind of industry standard stuff, but that doesn't necessarily mean that you have to do everything exactly as they say. Especially when the majority of the examples you'll find online have to do with science, and so it'll be like, include data chart of this whatever, and then you're like uh . . . I don't have that kind of data. Um, which is why I think doing this would be a really cool way of being like, look at my data.

Figure 6. New media tutoring session transcript #3. A computer science major with pre existing new media knowledge (Tutor 1) and English literature major who had recent practice composing a research poster (Tutor 2) express greater confidence in assisting a writer new to multimodal composing.

The study results speak to a productive level of engagement and improvement in each of the multimodal composing tutorials; writers were afforded sound advice from tutors with working knowledge of new media composing strategies that could improve the quality of the new media project at hand. Yet two of the three most prevalent patterns that emerged from the transcript data suggest generalist tutors' new media composing advice was clouded by a lack of confidence in that working knowledge, which has the potential to undermine or otherwise negatively impact the overall effectiveness of individual tutoring sessions.  Even when tutors (1) structure sessions productively (in a global-local-global sense), those sessions may be adversely affected if the tutor feels compelled to (2) undercut the credibility of their new media composing advice or (3) wait for the writer to forward new media composing ideas if the tutor has no disciplinary resources or recent practice of their own to draw on. The transcripts did not paint a picture of individual sessions crashing and burning, if you will, but, as a writing center director, I felt compelled to engage in follow-up discourse with the tutor in Transcript 2 regarding their tendency to apologetically qualify their new media composing advice. I also may have had a moment of existential angst regarding Transcript 3: concern about what gaps I may not be able to fill when the pools of tutors with complementary disciplinary expertise and fortuitous out-of-center practice run dry. While working knowledge may afford potential or temporary successes, tutors may need more than "working confidence" to create and sustain a tutoring environment in which new media composing strategies can be productively imparted and effectively retained to make writers better writers.

Even when tutors (1) structure sessions productively (in a global-local-global sense), those sessions may be adversely affected if the tutor feels compelled to (2) undercut the credibility of their new media composing advice or (3) wait for the writer to forward new media composing ideas if the tutor has no disciplinary resources or recent practice of their own to draw on. The transcripts did not paint a picture of individual sessions crashing and burning, if you will, but, as a writing center director, I felt compelled to engage in follow-up discourse with the tutor in Transcript 2 regarding their tendency to apologetically qualify their new media composing advice. I also may have had a moment of existential angst regarding Transcript 3: concern about what gaps I may not be able to fill when the pools of tutors with complementary disciplinary expertise and fortuitous out-of-center practice run dry. While working knowledge may afford potential or temporary successes, tutors may need more than "working confidence" to create and sustain a tutoring environment in which new media composing strategies can be productively imparted and effectively retained to make writers better writers.

Follow-up Survey

In a follow-up survey, I asked my tutors participating in the videotaped and transcribed new media tutorials to ". . . describe the effectiveness of the session in terms of its likelihood in resulting in successful revision and how, in your view, an understanding of multimodal/technology-rich writing played a role in the session." The following is a representative tutor response: "The session was very effective. As a tutor, I understood the project and the elements of the project that were affecting the overall visual rhetoric. I was able to communicate this to the tutee, and she responded in a way that indicated that she understood and was willing to make the changes I had suggested—she even made several of the changes during the consultation." Because (among other reasons) the writers immediately incorporated some of the tutors' suggestions, the tutors were convinced of the effectiveness of the sessions. Tutors were able to leverage their working knowledge of visual rhetoric to encourage writers to assess and enact new media composing choices during consultations. As a researcher, I interpreted these consistent responses to indicate that my tutors possessed a working knowledge of new media composing: an "understanding" was being exchanged. Yet, because "working knowledge" and "working confidence" are not the same thing and do not necessarily afford the same tutoring results, I further asked my tutors to report their new media tutoring knowledge as "no knowledge," "working knowledge," or "expert knowledge" alongside rating their comfort/confidence with new media tutoring as "none," "working," or "expert." One tutor reported "expert" on both accounts, while each of the remaining tutors reported "working" on both accounts.

The most revelatory results came when I asked my tutors whether they considered themselves primarily or in some capacity "new media tutors." While half of the participants responded "yes," the other half responded similarly to the following: "No. While I am confident that I can offer some useful multimedia-specific help to tutees, I am less comfortable working with digital media, largely because I do not consider myself a technologically-savvy person in general " (emphasis added). Even with a "working knowledge" and a "working confidence," tutors only saw themselves as competent in offering new media composing advice in isolated instances. I believe this response is inspired largely by the nature of engagement; when asked "how often do you find yourself employing your new media knowledge in writing consulting," most of my tutors responded "very seldom." If tutors explicitly engage with a single project in their training course and "very seldom" engage with such projects in their daily tutoring work, then how can a director reasonably expect their tutors to project anything more than a working confidence?

The most revelatory results came when I asked my tutors whether they considered themselves primarily or in some capacity "new media tutors." While half of the participants responded "yes," the other half responded similarly to the following: "No. While I am confident that I can offer some useful multimedia-specific help to tutees, I am less comfortable working with digital media, largely because I do not consider myself a technologically-savvy person in general " (emphasis added). Even with a "working knowledge" and a "working confidence," tutors only saw themselves as competent in offering new media composing advice in isolated instances. I believe this response is inspired largely by the nature of engagement; when asked "how often do you find yourself employing your new media knowledge in writing consulting," most of my tutors responded "very seldom." If tutors explicitly engage with a single project in their training course and "very seldom" engage with such projects in their daily tutoring work, then how can a director reasonably expect their tutors to project anything more than a working confidence?

Indeed, tutors demonstrated, fairly consistently, a clear "working knowledge" of new media consulting, as evidenced by integration of new media composing concepts alongside foundational rhetorical principles. On one hand, these are desirable results: my instructional design, a single Visual Rhetoric in Practice assignment, was meant to afford writing tutors with a working knowledge of new media composing strategies. On the other hand, the videotaped and transcribed sessions and follow-up survey results suggest that tutors may need more than "working confidence" to create and sustain a tutoring environment in which new media composing strategies can be productively imparted and effectively retained to make writers better writers—without tutors undermining their own new media composing advice in individual tutoring sessions or directors relying on fortuitous technology-rich composing education opportunities embedded in tutors' out-of-center coursework and extracurricular activities.

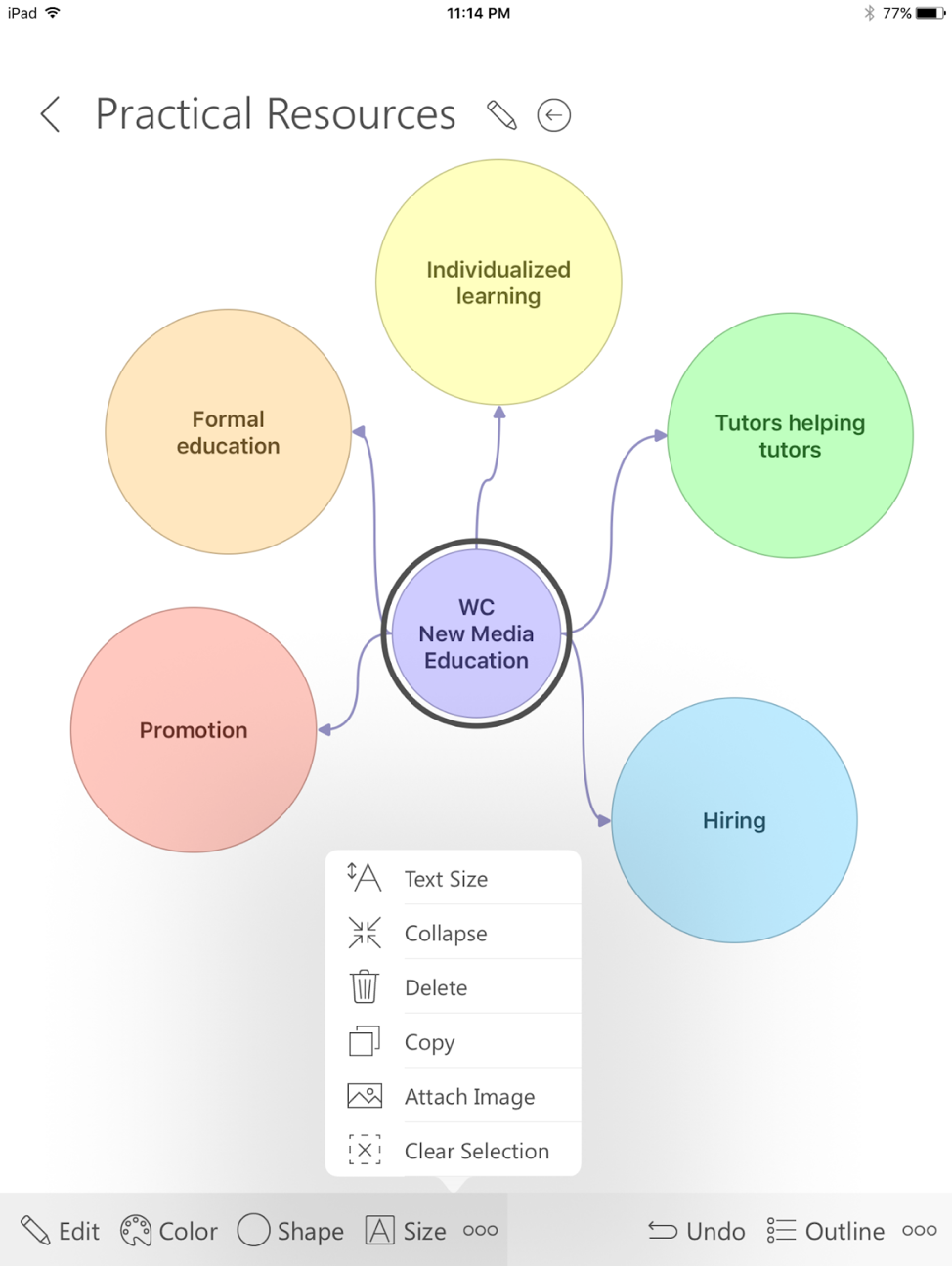

Suggestions and Resources for New Media Tutor Education

With due acknowledgement to its limitations as a local case study, the present work demonstrates the importance of educating our tutors to competently, and confidently, tackle complex new media composing challenges; after all, "writing has evolved with new composing technologies and media, and we must evolve, too, because we are in the writing business" (Grutsch McKinney 255). There are plenty of texts, such as Grutsch McKinney's "New Media Matters: Tutoring in the Late Age of Print," that have established the need for writing center practitioners to turn our already taxed attention to supporting new media composing. There are far fewer texts that have assessed how: how can we efficiently and effectively integrate and sustain new media tutor education in existing writing center programs? The results of my empirical investigation show that a single Visual Rhetoric in Practice assignment in a pre-employment tutor education course may afford tutors working knowledge of new media composing but that those same tutors do not yet see new media composition as integral to their generalist tutoring identities or at least risk underperformance in consistent and confident expression of new media composing advice. So, what can writing center practitioners do to build tutors' new media composing confidence? In this section, I offer practical suggestions for implementing new media education into existing writing tutoring programs—resources I have turned to in the past as well as strategies I intend to employ in the future based on the results of this study and on my continued scholarly engagement with the larger field of rhetoric, technology, and digital writing. I offer both small-scale and larger time- and money-intensive investments to support writing centers in a variety of institutional contexts. I present suggestions and resources in the following five areas: promotion, formal education, individualized learning, tutors helping tutors, and hiring.

An intuitive way to get tutors more practice with new media composing is to funnel more multimodal project traffic into the writing center. I recently asked my tutors to serve as "Department Ambassadors," sitting in on disciplinary  department meetings to inquire about each department's relationship with the writing center. We started with departments with which we had already established relationships—they had been sending writers to us or we had already reached out to encourage as much. We framed it as an assessment effort to garner feedback about the efficacy of writing center services and how we might better serve their students, specifically. We asked, "What types/kinds of writing do students in your discipline do?" "What writing-related issues do students in your discipline struggle with?" and "How can the writing center better help your students?" When it came time to pitch writing center services, especially to those departments with whom we were less familiar, we found that most weren't cognizant of the multimodal services we offered but that they would be enthused to assign more multimodal composing projects knowing this support was in place. Highlighting the disciplinary diversity of the writing center staff proved particularly persuasive in this regard as multimodal composing expertise is often associated with particular majors and minors, such as computer science, graphic design, or film and visual narrative.

department meetings to inquire about each department's relationship with the writing center. We started with departments with which we had already established relationships—they had been sending writers to us or we had already reached out to encourage as much. We framed it as an assessment effort to garner feedback about the efficacy of writing center services and how we might better serve their students, specifically. We asked, "What types/kinds of writing do students in your discipline do?" "What writing-related issues do students in your discipline struggle with?" and "How can the writing center better help your students?" When it came time to pitch writing center services, especially to those departments with whom we were less familiar, we found that most weren't cognizant of the multimodal services we offered but that they would be enthused to assign more multimodal composing projects knowing this support was in place. Highlighting the disciplinary diversity of the writing center staff proved particularly persuasive in this regard as multimodal composing expertise is often associated with particular majors and minors, such as computer science, graphic design, or film and visual narrative.

To support a culture of sustained, critical engagement with multimodal composing, in the Fall of 2018 I am implementing a one-credit practicum that all employed tutors will be required to take. This one-credit practicum is for tutors who just completed their three-credit writing center theory and practice course in the spring as well as for any and all tutors continuing beyond one year of full time employment in my writing center. In other words, it is a one-hour, once-per-week opportunity for the entire staff to engage in explicit professional development activities together.

Increasing tutors' confidence in consulting technology-rich assignments requires narrowing the scope of such a follow-up practicum to suit more specialized (new media-specific) needs: offering a curriculum scaffolded to address making invisible modal choices visible, facilitating meaningful access (see Banks), and, most importantly, engaging in a series of multimodal composing assignments. A follow-up practicum that requires tutors to engage in assignments to exercise their new media composing skills each week would inherently afford tutors the regular practice and reflection likely leading to above-and-beyond "working confidence" in technology-rich consultations.

One option for productively tailoring such practicum assignments includes targeting narrowly defined multimodal composing choices, such as formatting and placing text, manipulating lines and shape, or adding and combining color.

I also recommend taking advantage of the new media composing software that is readily available and already in use by stakeholders across your campus. Researching software availability and use is a warranted investment of your time and energy as it will allow you to maximally tailor your practicum assignments to student access and instructor investment. In my institutional context, tutors might execute an interface analysis and evaluative presentation on Adobe InDesign, compose an instruction set for a particular InDesign tool (perhaps collected on a class community wiki), and, finally, produce scholarly web texts through the affordances of InDesign as a composing platform.

Further, you might directly correlate practicum assignments with center needs for promotional materials, staff professional development, or outreach opportunities. In the past, outside the confines of a practicum, I have had tutors compose stickers, mini-flyers, posters, vidcasts, and other web resources (see Figures 7, 8, and 9).

Integrated as a practicum assignment sequence, product-oriented projects should build in complexity of multimodal decision-making over the course of the semester and could be executed by individual or collaborative means.

Ultimately, I advocate the need for follow-up reflection, a concerted effort on the part of participating tutors to actively and explicitly process and build upon their growing multimodal composing expertise. As one example, I offer the assignment prompt for my Visual Rhetoric in Practice exercise (including a heavily weighted reflective essay) as an appendix to this chapter. I caution readers to consider how the assignment may best fit their own institutional needs, especially given that the assignment was designed to stand alone and was not originally designed as part of a scaffolded series of assignments, precluding the sustained engagement with new media composing education opportunities I am arguing for.

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

| Figure 7. Whitworth Composition Commons (WCC) sticker. Created by and reproduced with permission from Angela Baik and the 2017-2018 WCC Social Media and Promotional Materials Task Force (Audrey Chang, Alli Kieckbusch, and Erin Wolf). | Figure 8. Whitworth Composition Commons (WCC) social media mini-flyer. Created by and reproduced with permission from Alli Kieckbusch and the 2017-2018 WCC Social Media and Promotional Materials Task Force (Angela Baik, Audrey Chang, and Erin Wolf). | Figure 9. Font poster. Created by and reproduced with permission from Alexandra Begley. |

At institutions where time and money are scarcer, practitioners can point their tutors to rich multimodal composing resources freely available on the web, such as the Adobe Education Exchange, where you can "download free tutorials, projects, and lessons to teach digital media." These self-paced and online community-supported tutorials can be undertaken by tutors or practitioners as a part of required or voluntary professionalization.

Promoting such accessible, sustained engagement with new media composing through individualized learning is a low-cost investment in helping tutors gain confidence. Below I share how I utilize low-cost multimodal composition resources to teach tutors about C.R.A.P. (contrast,repetition, alignment, and proximity), typography, color, copyright and Creative Commons, and software.

C.R.A.P.

The Non-Designer's Design Book (now in its fourth edition) has long been praised for its clear and careful explication of the four basic principles of design: contrast, repetition, alignment, and proximity (Chapters 2–5). I started with these basic definitions and created a PowerPoint full of advertisements that illustrate how the C.R.A.P. principles combine through visual hierarchy to convey a message to an audience (see Figure 10). Advertisements, such as Rohto's "Feel the Eyedrenaline," make ample engaging fodder for building a common, foundational multimodal tutoring language, and a common tutoring language is critical to building staff-wide confidence in proffering new media composing guidance.

|

| Figure 10. Slides 4, 5, and 6 from "Visual Rhetoric: All the C.R.A.P. You Need to Know" pedagogical PowerPoint. Original screen capture by author. PowerPoint adapted by author. Original PowerPoint collaboratively authored by Technology Mentors of the Introductory Composition at Purdue program at Purdue University. |

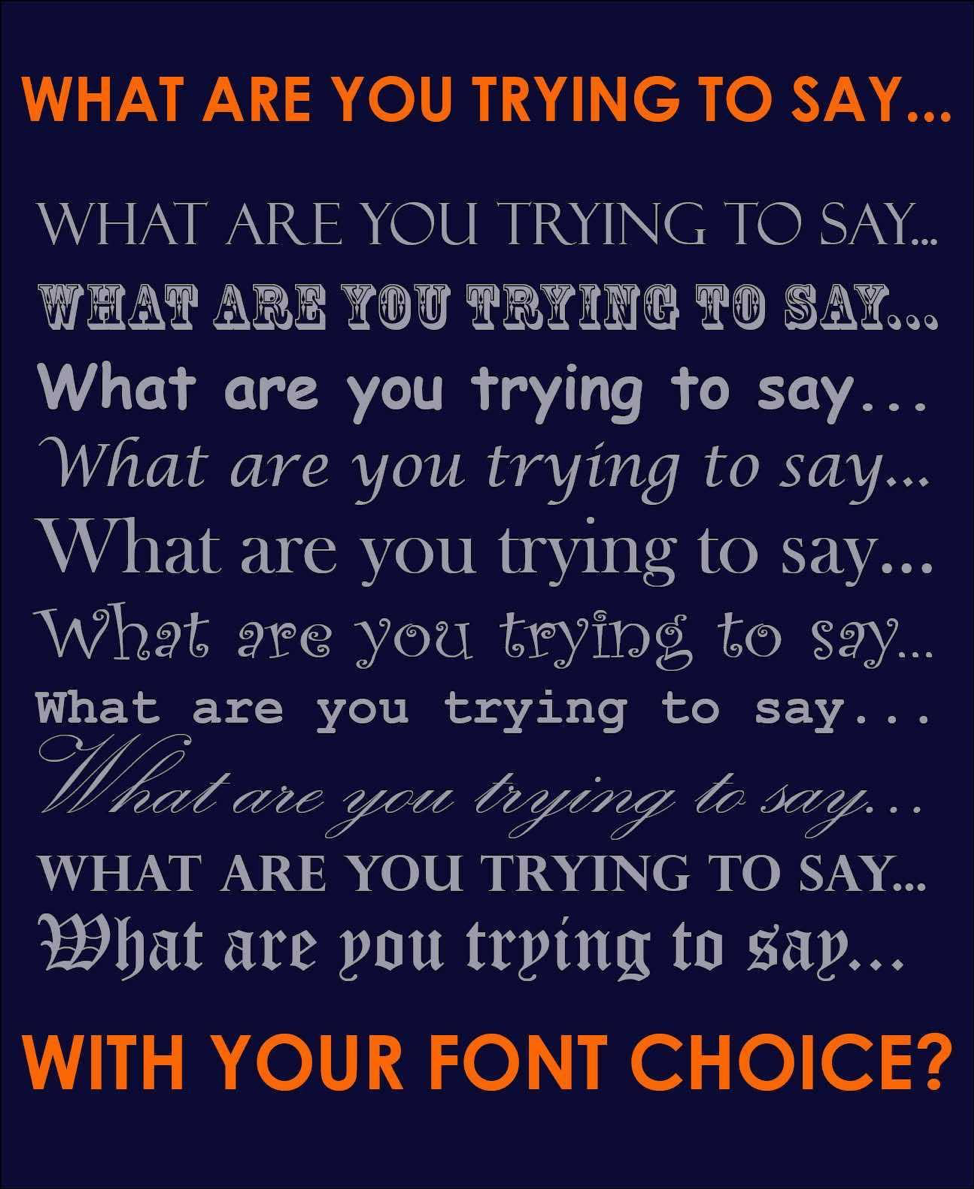

Typography.

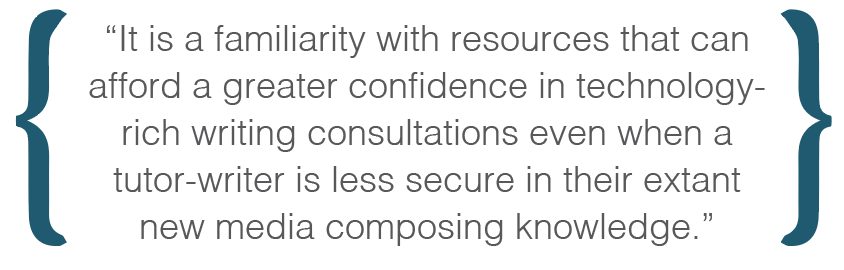

Writers often speak of being drawn toward particular types or kinds of fonts but lack the language to explain how or why some fonts function more effectively in certain composing contexts than others. The Purdue Online Writing Lab is a helpful starting point for discussing "Using Fonts with Purpose." Font personality, or why we wouldn't compose a professional e-mail in Curlz MT, for example, is well illustrated in College Humor's "Font Conference" video. I would recommend The Non-Designer's Design Book's "The Essentials of Typography" for a more advanced  understanding of things like sans/serif fonts, kerning, leading, etc., but "WhattheFont" is also a helpful tool that writers at any stage of multimodal expertise can use to identify fonts instantly. With "WhattheFont," users take a photo and tap the font they want to identify with immediate results. I emphasize "writers at any stage" here because it is a familiarity with resources that can afford a greater confidence in technology-rich writing consultations even when a tutor-writer is less secure in their extant new media composing knowledge. Indeed, foundational writing center theory and practice is based on the idea that confidence increases with access to resources. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors—an exemplar resource in and of itself—states that being a "writing expert" can mean "model[ing] how one can use available resources" (Ryan and Zimmerelli xii; 6).

understanding of things like sans/serif fonts, kerning, leading, etc., but "WhattheFont" is also a helpful tool that writers at any stage of multimodal expertise can use to identify fonts instantly. With "WhattheFont," users take a photo and tap the font they want to identify with immediate results. I emphasize "writers at any stage" here because it is a familiarity with resources that can afford a greater confidence in technology-rich writing consultations even when a tutor-writer is less secure in their extant new media composing knowledge. Indeed, foundational writing center theory and practice is based on the idea that confidence increases with access to resources. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors—an exemplar resource in and of itself—states that being a "writing expert" can mean "model[ing] how one can use available resources" (Ryan and Zimmerelli xii; 6).

Color.

A basic understanding of color theory goes a long way in crafting confidence in effective visual (multimodal) communication. There are a plethora of resources out there that introduce color theory, including the Purdue OWL and The Non-Designer's Design Book. Lesser-known and equally (if not more) compelling resources include Claudia Cortés's Color in Motion, described as "an animated and interactive experience of color communication and color symbolism," where writers can learn about color profiles and meanings as well as engage in activities that encourage the author to practice communicating specific messages through color (activities that could be integrated into more formal education initiatives!). There is also Adobe Color CC where writers can "create" color schemes according to various color "rules," transferring specific RGB and/or HEX codes to their composing software of choice. Adobe Color users can also "Explore" various schemes or themes that other users have created to represent particular feelings or messages they desire to communicate visually through color (see Figure 11).

|

| Figure 11. Adobe Color CC. Custom theme, "summer jams," created by Adam Trabold. Original screen capture by author. |

Copyright and Creative Commons.

It is also critical that multimodal writers be introduced to intellectual property and copyright law, just as any effective tutor would have confidence in discussing source integration and documentation in monomodal composing contexts. Copyright law can be complex and overwhelming, as this webpage illustrates: "Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States"; however, there are more user-friendly means for building a foundational understanding of and confidence in conveying how source borrowing and attribution works in multimodal composing contexts. "A Fair(y) Use Tale" is an accessible Disney parody explanation of copyright law and fair use. I would also advocate that tutors and the writers they work with be introduced to Creative Commons, a site that offers composers alternative licensing to copyright so that works may be circulated under "generous, standardized terms." More specifically, search.creativecommons.org allows writers to "find content you can share, use, and remix" that has been licensed through Creative Commons but made available by Google, Flickr, or YouTube, for example. I again reiterate that it is introduction and access to as well as explicit guidance in growing familiarity with new media composing resources that will ultimately ensure tutors' sustained confidence in technology-rich consultations over time.

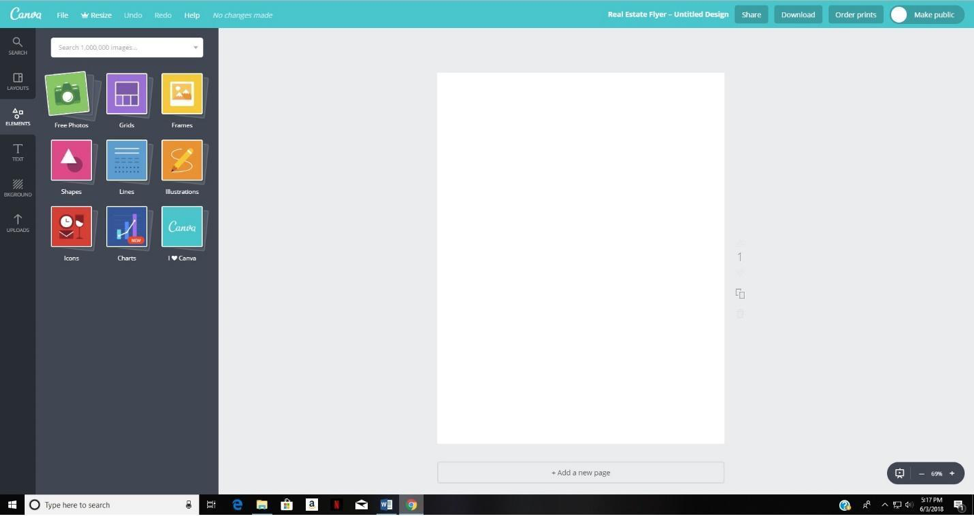

Software.

Not all writers will have privileged access to industry-leading composing software such as Adobe InDesign. That is why I make a point to introduce my tutors to open-source alternatives (Lynch), such as Canva or Scribus (see Figure 12). By "introduce," I mean "mention" or "cursorily present." The constraints of time for continued education do not often allow for multiple in-class or staff-meeting sessions dedicated to step-by-step software tutorials; however, in introducing my tutors to one program, Adobe InDesign, through formal education, they become familiar with how similar tools generally function. They often have success, then, when they attempt to navigate the less expansive and less complex composing interfaces of such alternatives. In fact, I encourage a tutor culture of "tinkering" (see the work of Jentery Sayers, among others), allowing time for "playing" with various software programs (open-source programs to Microsoft Publisher to Adobe InDesign) during downtime, to help tutors ascertain the various affordances and constraints of each. When tutors are afforded low-stakes opportunities to exercise their working knowledge of new media composing, their confidence increases, resulting in a greater likelihood of effective advice being consistently proffered in higher-stakes situations (one-to-one or small-group consulting with writers).

|

| Figure 12. Canva user interface. Original screen capture by author. |

Concern about practitioner new media expertise is valid and can be ameliorated by taking advantage of what writing centers are best known for: peer-led learning. I implemented a task force model in my writing center to organize research and development among tutors. Tutors pursue task force work during downtime and have been required to engage their peers in directed education at staff meetings. The Technology Task Force, for example, has researched and educated us on iPad applications for multimodal composing (such as brainstorming apps like Notes, Penultimate, and Ideament (see Figure 13) or speech-to-text applications like Dragon. Other options include crafting a "technology yellow pages," which starts with a "technology assessment" asking tutors to identify comfort level with new media composing skills such as word-processing, web development, graphic design, video animation, and sound editing. The practitioner compiles this information alongside tutor contact information for an easily accessible list of who knows what about composing with technology. Practitioners might also consider facilitating formalized peer mentor relationships—pairing tutors with contrasting levels of new media composing expertise—with the goal of jointly increasing tutor mentors' and mentees' new media composing confidence.

|

| Figure 13. Screen capture of the "Practical Resources" mind map created by the present study's author in the Ideament brainstorming app on an iPad. Original screen capture by author. |

My "Peer Mentor Program and Consulting Philosophy Project" requires current tutors and tutors in the writing center theory and practice preparation course to complete informal beginning-, middle-, and end-of-semester "check-ins." As paired peer mentors and mentees, they must also complete practical engagement activities such as a writing center operations review, a client report form logistics review, and an introduction to writing center technology review. Formal observation of task force meetings and workshops is also required for successful project completion. I further recommend that peer mentor pairs facilitate shift shadowing, engage in mock or team consultations, and jointly participate in outreach events. As a final required "activity," mentor-mentee pairs consult with one another to draft or revise their individual writing tutoring philosophies. When tutors are matched specifically regarding their current level of new media writing tutoring expertise, they are afforded a variety of organic and less time-intensive opportunities for experiencing new media tutoring expertise in action. Peer mentor pairs may be encouraged, then, to explicitly reflect on the role of new media composition in their tutoring as they complete the culminating exercise of crafting or updating their consulting philosophies at the end of the academic year—an explicit exercise in chronicling increased confidence in writing tutoring generally but also new media composition consulting more specifically.

Whether you operate a generalist, specialist, or hybrid generalist/specialist writing center, you have the opportunity to inventory and assess your potential tutors' new media proficiencies through the recruitment, application, and/or interview processes. My center's writing tutor application, for example, asks applicants to speak to the following question: "Any specialized areas of expertise (i.e., ELL, business/technical writing, creative writing, multimodal writing, etc.)?" In the follow-up interview, applicants are asked to review an example PowerPoint presentation or resume and to speak to its strengths and weaknesses in design as well as how they would engage its author in a tutorial, giving the interviewer a sense of the applicant's baseline new media composing expertise and confidence in a consulting situation.

Conclusion

What I have learned from this empirical study is that a working knowledge of new media composing is productive—desirable, even. And a single tutor education course assignment such as Visual Rhetoric in Practice can successfully foster that working knowledge. If we are looking for our tutors to consistently impart that working knowledge with optimum effectiveness in a variety of multimodal composing situations, however, then we must also attend to confidence. That is, heeding Grutsch McKinney's and others' calls to embrace the evolution of technology-rich  twenty-first century writing and to attend to new media composition as a significant—if not an inherent—component of our contemporary writing center support praxis requires fashioning tutor education that does not leave generalist tutors feeling compelled to consistently hedge their multimodal composing advice. We need to better support writing tutors who are not already embedded in specialist disciplines invested in multimodal composing practice, tutors who may feel at a loss for ideas when it comes to working with writers on projects like infographics, research posters, or scholarly web texts. The results of this study suggest that tutors with working knowledge of new media composing have valuable advice to offer the writers they consult with, but they just don't feel confident in delivering that advice. So, if we want to decrease opportunities for writers to doubt the authority of tutors' (constructive!) new media composing advice, and if we want tutors to feel as confident in the resources they have for tutoring white paper design as they are confident in tutoring first-year composition rhetorical analyses, then we must provide sustained engagement with new media composing in our tutor education practices.

twenty-first century writing and to attend to new media composition as a significant—if not an inherent—component of our contemporary writing center support praxis requires fashioning tutor education that does not leave generalist tutors feeling compelled to consistently hedge their multimodal composing advice. We need to better support writing tutors who are not already embedded in specialist disciplines invested in multimodal composing practice, tutors who may feel at a loss for ideas when it comes to working with writers on projects like infographics, research posters, or scholarly web texts. The results of this study suggest that tutors with working knowledge of new media composing have valuable advice to offer the writers they consult with, but they just don't feel confident in delivering that advice. So, if we want to decrease opportunities for writers to doubt the authority of tutors' (constructive!) new media composing advice, and if we want tutors to feel as confident in the resources they have for tutoring white paper design as they are confident in tutoring first-year composition rhetorical analyses, then we must provide sustained engagement with new media composing in our tutor education practices.

Works Cited

Adobe Systems. Adobe Color CC, 2016, color.adobe.com.

—. Adobe Education Exchange, 2017, edex.adobe.com.

Ball, Cheryl E., et al. Writer/Designer: A Guide to Making Multimodal Projects. 2nd ed., Bedford, 2018.

Banks, Adam. Race, Rhetoric, and Technology. Lawrence Erlbaum, 2006.

"Color Theory Presentation." The Purdue OWL, Purdue U Writing Lab, 1995-2018, owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/715/1/.

Conard-Salvo, Tammy. English 390-A01: Tutoring Practicum in Writing for First Year Composition. Fall 2016. web.ics.purdue.edu/~tcsalvo/ English390A/syllabusfall2016.pdf.

Cortés, Claudia. Color in Motion, vimeo.com/129112056.

Creative Commons. "About the Licenses." Creative Commons, Creative Commons, 7 Nov. 2017, creativecommons.org/licenses/.

—. "Frequently Asked Questions." Creative Commons, Creative Commons, 7 Mar. 2018, creativecommons.org/faq/.

—. "Search." Creative Commons, Creative Commons, search.creativecommons.org. Accessed 26 Apr. 2018.

Dinitz, Sue, and Susanmarie Harrington. "The Role of Disciplinary Expertise in Shaping Writing Tutorials." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 33, no. 2, 2014, pp. 73-98.

"A Fair(y) Use Tale." YouTube, uploaded by Jas A, 18 May 2007, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CJn_jC4FNDo.

"Font Conference." YouTube, uploaded by CollegeHumor, 28 July 2008, www.youtube.com/watch?v=i3k5oY9AHHM.

Grutsch McKinney, Jackie. "New Media Matters: Tutoring in the Late Age of Print." Writing Centers and New Media, edited by Sohui Lee and Russell Carpenter, Routledge, 2014, pp. 242-56.

Hirtle, Peter B. "Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States." Cornell University Library Copyright Information Center, Cornell University, 10 Jan. 2018, copyright.cornell.edu/publicdomain.

Lee, Sohui, and Russell Carpenter. "Introduction: Navigating Literacies in Multimodal Spaces." Writing Centers and New Media, edited by Sohui Lee and Russell Carpenter, Routledge, 2014, pp. xiv-xxvi.

Lynch, Ryan. "5 of the Best Free Adobe InDesign Alternatives." Make Tech Easier, Uqnic Network Pte, 6 Mar. 2018, www.maketecheasier.com/free-adobe-indesign-alternatives.

Mentholatum. "Rohto Eye Drops: Feel the Eyedrenaline." www.adforum.com/creative-work/ad/player/34443434/na/rohto-eye-drops.

MyFonts. "WhatTheFont Mobile App." MyFonts, MyFonts, 1999-2018. www.myfonts.com/WhatTheFont/mobile.

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. 6th ed., Bedford, 2016.

Sayers, Jentery. "Tinker-Centric Pedagogy in Literature and Language Classrooms." Collaborative Approaches to the Digital in English Studies, edited by Laura McGrath, Utah State UP, 2011, ccdigitalpress.org/book/cad/Ch10_Sayers.pdf.

"Using Fonts with Purpose." The Purdue OWL, Purdue U Writing Lab, 1995-2018, https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/visual_rhetoric/using_fonts_with_purpose/index.html.

Williams, Robin. The Non-Designer's Design Book. 4th ed., Peachpit, 2015.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was made possible, in part, by a Summer 2016 research fellowship granted to me on behalf of the Faculty Research and Development Committee of Whitworth University. My gratitude also goes to the Whitworth Composition Commons writing center consultants who participated in the taping and transcribing of materials for this project in Spring 2016. Finally, this work would not be nearly as rigorously and accessibly presented without the careful guidance of Ted Roggenbuck, Karen Johnson, and many other WLN reviewers along the way.

BIO

Jess Clements (jclements@whitworth.edu) is Assistant Professor of English and Director of the Composition Commons at Whitworth University. She has served as Style Editor for Present Tense since 2012. Her scholarship centers on ethos and the role of human and object-oriented actors in contemporary multimodal communication. She is currently collaborating on an interdisciplinary book evaluating the influence of social media networks in shaping binary-bound parenting decisions that evolve in spaces where quantitative evidence is conflicting. She is also pursuing projects that examine the pedagogical performance of faith in the first-year writing classroom as well as the influence of technological actors in writing center-community partnerships.