|

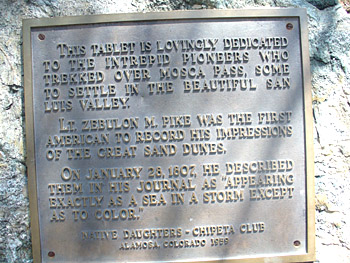

Brass

plaques abound. Free standing or more often embedded in some structure

even more permanent, such as a basalt boulder or a twenty-story steel

and granite building, plaques serve a rhetorical not an architectural

purpose. Their military colors, sharp edges, and upper-case hieratic

fonts make two pronouncements about the site or the building: appropriation

and origination. They shout that this place belongs to X because X did

Y first. A brass commemorative plaque is the metallic equivalent of

the planting of a flag. It is not surprising that in terms of truth-statements

plaques are often tissue thin.

In

January of 1807 Zebulon Pike and ten men crossed the Sangre de Cristo

Mountains from east to west, probably using what today is called the

Medano Pass west of Pueblo, Colorado. As he notes in his journal, coming

down the west side of the mountains they saw the Great Sand Dunes, which

pile up against the mountains on the eastern edge of the San Luis Valley

(the photograph captures something like the view). It was a picturesque

moment in the middle of a disastrous expedition, sandwiched between

failing to discover the headwaters of the Red and the Arkansas rivers,

trekking in circles through the wintry Colorado Rockies, unsuccessfully

attempting to climb what we today call Pike's Peak, leaving exhausted

men without food behind in the snow, and being captured by the Mexican

military and sent under guard to Chihuahua and eventually turned over

to U. S. authorities in Natchitoches.

None

of this is mentioned by the Chipeta Club of the Native Daughters of

Alamosa, Colorado, who commissioned the plaque pictured above. It stands

at the western head of a trail that follows Mosca Creek from the Great

Sand Dunes up to the top of Mosca Pass--which Zebulon Pike probably

did not travel. It also sanctifies Pike as "the first American

to record his impressions of the Great Sand Dunes." This is a blatant

act of appropriation and origination. It disregards, for instance, other

Americans--native Americans--who had in their own rhetorical ways recorded

their impressions of the Great Sand Dunes for centuries before Pike

and his companions saw them in 1807. The Utes called the Dunes sowapophe-uvehe,

"the land that moves back and forth," and the Jicarilla Apaches

called them ei-anyedi, "it goes up and down." Also

the Spanish had been exploring, trading, and settling in the San Luis

Valley since 1692, giving them a century of opportunities before Pike

to record their impressions of the Great Sand Dunes, which are visible

from any part of the Valley on a clear day. The only reasonable claim

to origination with Pike's journal entry is if we read "first American"

to mean "first Anglo U. S. citizen" and "record"

to mean "inscribe in English on paper that has survived and is

known to historians." Even that claim could easily be untrue.

Indeed,

it is a claim that probably will not survive as long as the brass plaque

planted at the foot of Mosca Canyon by the Native Daughters of Alamosa.

For a delightful exposé of the inaccuracies perpetuated in commemorative

sites in the USA, see James W. Loewen Lies Across America: What

Our Historic Sites Get Wrong (New York: New Press, 1999). The Indian

names for the Great Sand Dunes I found in the National

Parks website. Incidentally, Pike's entry reads, "Their appearance

was exactly that of a sea in a storm, except as to color," which

the plaque slightly misquotes.

RH,

August 2008

|