|

Is

the photograph above a fib? Two standard answers to this question say

no, but for different reasons. Received knowledge tells us that photographs

don't lie. Postmodernism tells us that the question has no answer because

outside of discourse, within which truth claims aways reside, no discourse

exists to decide the claim. It seems either the photograph is telling

the truth or truth-telling itself is moot. Well, a fig to everyone,

including postmodernists. I say this photograph lies. The proof is in

the pudding, and here's my proof.

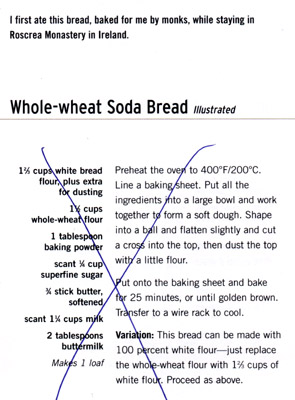

A

photograph is always part of an argument, and this one's argument is

hardly disputable. It is offered in a bread-making cookbook by Paul

Hollywood, 100 Great Breads (New York: Barnes & Noble Books,

2004, pp. 26-27). The picture, verso, is of Whole-wheat Soda Bread and

the recipe for it stands recto. The argument is that if the recipe is

followed faithfully, the cook will end up with a loaf like the one in

the photograph—and what a delectable loaf it looks! I trusted

the argument, followed the recipe, and ended up with a dough so unbreadlike

I didn't even waste time trying to bake it. Hence the exasperated X

through the recipe. I might just as well have X'd the photograph of

the loaf, though. Both are lies. The recipe says, "Follow me and

that loaf will be yours." The photograph says, "Want me and

all you have to do is follow that recipe." Taken alone, unapplied,

maybe neither picture or text can be said to lie. Together, applied,

they lie.

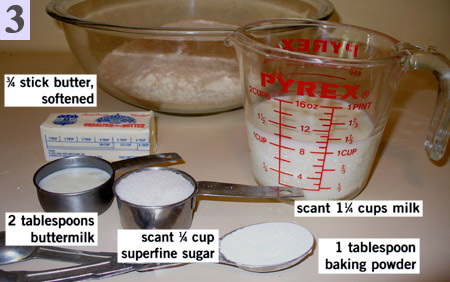

Or

maybe my application was in error. So I made the recipe again and documented

it step by step. With photographs, of course. Here's my proof. You judge.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

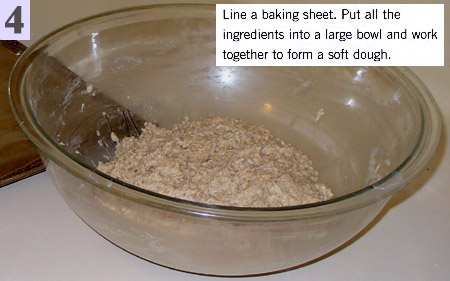

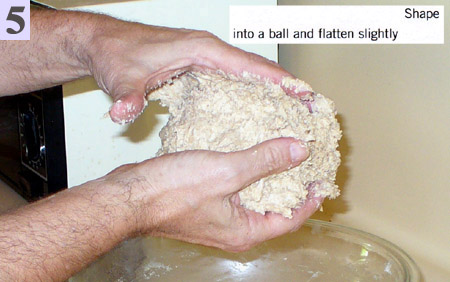

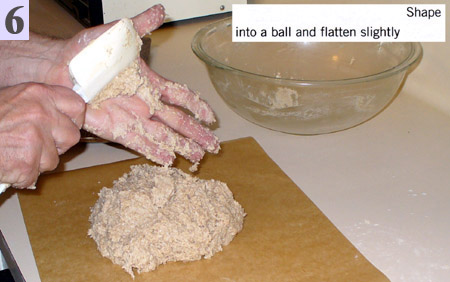

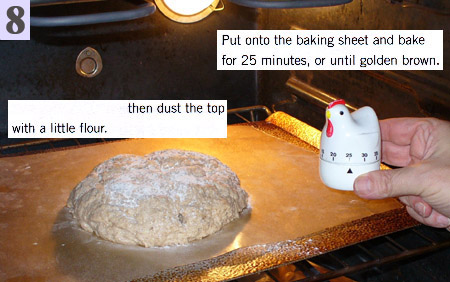

In

words, the ingredients mixed up into a dough with a consistency

closer to bread pudding than bread. With wet hands, I was able

to "shape" and "flatten" it into a form

that, to my farm boy eyes, looked like a healthy cow flop. Impossible

to cut much of a cross because the dough stuck to the sharpest

knife. Flour "sprinkled" on it congealed on contact.

But I baked the sad affair at the stipulated temperature for

the stipulated time, and it came out of the oven with the stipulated

"golden brown" color. I cooled it thoroughly on a

rack.

The

outcome was a loaf shaped like a mushroom cap, the center of

which was still so doughy that even Luna (the dog) was reluctant

to eat it.

Compare

the next two photographs and decide which one is telling the

truth of this recipe.

|

|

|

I've been baking bread for a quarter of a century and know the leeway

built into bread recipes--allowance for different flours, fluctuation

in weather humidity, idiosyncratic kneading habits, elevation above

sea level,

age of baking soda,

tolerance of oven temperature settings, etc. As Graham Tomlinson demonstrates

in an essay on the need to interpret food recipes, even a direction

as forthright as "1/3 cup chopped onion," obliges hermeneutic

and

practical

activity on the cook's part that is neither single nor simple ("Thought

for Food: A Study of Written Instructions," Symbolic Interaction,

9.2, 1986, pp. 201-216). But no culinary savoir-faire could

have converted this recipe into the pictured loaf without altering the

basic measurement of ingredients asserted in the recipe itself (as another

test, compare its ratio of dry to wet ingredients to that of other Irish

soda bread recipies).

Can

a recipe/picture lie? Of course it can, as any cook knows. Truth inheres

in discourse because discourse is not just words and pictures on the

page. Discourse happens. Discourse is nothing until enacted. In another

essay from the journal Symbolic Interaction, "Telling

the Truth after Postmodernism" (19.3, 1996, 203-223),

Dorothy E. Smith scrutinizes the way instructional discourse is socially

performed and concludes that it is in the performance that truth is

constituted. Scientific reports, street maps, recipes, and a multitude

of other discourse practices turn out to be truthful or not "in

locally accomplished social acts that complete the sequence of referring,

finding and recognizing 'same' objects and recognizing them as the same"

(pp. 190-191). Thus have some findings of scientists been discovered

to be incorrect, your friends' map to their house wrong, or that cursed

bread recipe not the same one that produced the bread in the photograph.

RH—March,

2007

|