CompPanels: Images from

the Annals of Composition #36

Computers and Individualization

|

It

was an odd whim of college compositional history that staged two rival

enthusiasms during the same years (1970-1985): computing systems and

individualized instruction. To compositionists today the machinery of

automation and the pedagogy of “individual differences”

seem contradictory in some obvious ways, but back then the two appeared

to go individual hand in computerized glove. It

was an odd whim of college compositional history that staged two rival

enthusiasms during the same years (1970-1985): computing systems and

individualized instruction. To compositionists today the machinery of

automation and the pedagogy of “individual differences”

seem contradictory in some obvious ways, but back then the two appeared

to go individual hand in computerized glove.

The yearning for the match is readily seen in a book from that era,

small enough to fit easily in one’s hand. Teaching Writing

with the Computer as Helper was written by J. Terence Kelly and

Kamala Anandam and published as a 3.75" x 6.25" pamphlet in

1982 by the American Association of Community and Junior Colleges. The

book promotes a ten-year-old computer system at Miami-Dade Community

College that had been used, in part, for writing instruction. It was

a system that the authors insist "has the potential to individualize

instruction” (p. 16).Yet today we can detect contradictions in

the book's celebration of the marriage between computerization and individualization.

Our first clue is the cover to the book. If the computer is really an

instructional “helper,” why are there no humans in sight?

All we see is a Telex Model 5403 printer (it automatically typed input

from the mainframe). Photographs inside the book send the same message.

We see either computing equipment tended by computer specialists (here

is author Kelly with a bank of open-reel tape recorders) or students

tended by teachers in old-fashioned, pencil-in-hand, pre-computer

ways. Students and computers are separated.

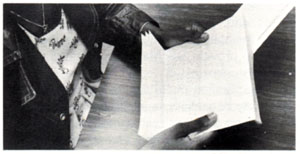

Graphically, the closest students and computers approach one another

is in a photograph of a student holding some sheets of computer paper

that have been folded to fit inside a legal-size mailing envelop. The

student is reading the computer’s print- out

of a response to her last essay. The envelope was delivered to her by

her teacher. The teacher had created the response by reading the student’s

paper and then marking a bubblesheet of writing criteria, which the

computer had turned into the letter, with boilerplate amenities (“Thank

you for turning in Assignment 1”), boilerplate diagnosis (“Verb

Usage: Shift in Tense’), and boilerplate illustration of error

(“Verbs change in form to show the time of their action: Read

the following paragraph”). This computerized teacher's aide is

cleverly named RSVP: Response System with Variable Prescriptions. It

also kept records. Kelly and Anandam contrast photos of a messy handwritten

gradebook with the tidy RSVP bubblesheet, and hand-written teacher commentary

on a student essay with the printed computer letter. out

of a response to her last essay. The envelope was delivered to her by

her teacher. The teacher had created the response by reading the student’s

paper and then marking a bubblesheet of writing criteria, which the

computer had turned into the letter, with boilerplate amenities (“Thank

you for turning in Assignment 1”), boilerplate diagnosis (“Verb

Usage: Shift in Tense’), and boilerplate illustration of error

(“Verbs change in form to show the time of their action: Read

the following paragraph”). This computerized teacher's aide is

cleverly named RSVP: Response System with Variable Prescriptions. It

also kept records. Kelly and Anandam contrast photos of a messy handwritten

gradebook with the tidy RSVP bubblesheet, and hand-written teacher commentary

on a student essay with the printed computer letter.

Teachers could write individual messages on a student's paper if they

wished, but the computer system did not permit anything other than boilerplate

text in the letter to the student. Understand that RSVP used mainframe

technology of the 1970’s, before PCs and LANs were feasible for

university instruction—and, I can’t resist adding, apparently

before the American Association of Community and Junior Colleges acquired

computerized text-editing capability (although most publishers had it

by that time), at least inferring from the misspelling of their own

name on the cover to this book.

So how does RSVP promote individualized instruction? Kelly and Anandam

are quite open about this question, but their argument is a little mysterious.

The impersonality of the computer will “equalize” teacher

and student relations, and its speed will give teachers more time to

work one-on-one with students (p. 13). It seems the computer doesn’t

individualize instruction, teachers do. But its efficient delivery system

reduces “the drudgery and repetitiveness, which English teachers

have had to deal with in scoring students’ essays” (p. 6).

It is an argument that predates computers, of course. Ever since the

late 19th century the word “drudgery,” for instance, has

been a writing-teacher code term, used to sell a grab bag of labor-saving

devices, from criteria sheets, error symbols, lay readers, peer critique,

overhead transparencies, to actual rubber stamps. Now it is computer

house-elves willing to work for very long hours at very low wages.

Today “individualized instruction” does not have the éclat

it did in the 1960s and 1970s, and the defense of computers in writing

instruction has moved on to new machinery, new premises, and new rationales

(such as group identity). Another stage, another story.

RH, April 2006

Bibliographic note. Kelly and Anandam's pamphlet is

available on microfiche in the ERIC Document Reproduction Service, ED

214 583. An earlier version of their argument is "RSVP—an

Invitation to Individualize Instruction," Community and Junior

College Journal, March issue, 1978, pp. 24-26. For the compositional

history of the word “drudgery,” see Brian Huot, “Computers

and Assessment: Understanding Two Technologies,” Computers

and Composition 13.2 (1996), pp. 231-244; and my own “Automatons

and Automated Scoring: Drudges, Black Boxes, and Dei Ex Machina,”

in Patricia Ericsson and Rich Haswell (Eds.), Machine Scoring of

Students Essays: Truth and Consequences, Utah State University

Press (2006), pp. 57-78.

|