|

Telling Book Covers (VI):

Méconnaissance and Covers |

|

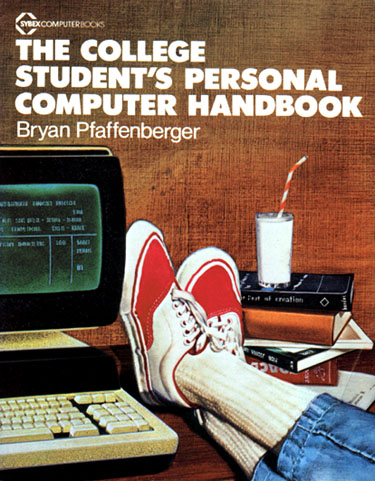

Book covers are well named, because they often function as méconnaissance, covering up realities that readers, writers, and assigners do not want to acknowledge. In this, composition books are no exception. Take another cover of an early book on computers and writing: Student's Personal Computer Handbook published by SYBEX in 1984. This is Bryan Pfaffenberger’s how-to book aimed at the first generation of students using personal computers for note taking, paper writing, and number crunching. Portrayed is a student not in the act of using his computer but taking a break from it. (I say his on the authority of my wife, who assures me that those are men’s socks.) Work is implied but it is leisure that is drawn. No doubt the message is that computers will save students time and make their educational labor easier. But the cover does not recognize the actualities of such labor: last-minute and late-night pounding out of a paper, consumption of alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine (milk, with a straw?!), frustrated rummaging through a desktop chaos of notes, paperclips, books, and greasy hamburger wrappings. On this cover even the books have unreadable pretend titles and publishers (closeup), as if this student did not partake in real student reading, which is often a thoughtless pillaging of half understood paragraphs. I can make out only the word "creation," which misrepresents the research-paper practices of many students. As Bourdieu notes, in a capitalistic society it is often labor that is deliberately snubbed in public. The sneakers are unscuffed. Inside the book, ink-wash cartoons execute the same méconnaissance, portraying the computer as a magician or happy editor, concealing the actual work that the student writer will have to do even with a computer. Recall composition-text covers that portray students in class—alert all, eager all, industrious all. Hardly a snapshot of an actual class. Certainly the covers are less realistic than the texts that they purport to represent. Pfaffenberger, for instance, makes no bones about the expense of owning a personal computer in 1984 (he estimates the cost, including peripherals, to be around $2,000). So in this cover, haves and have-nots is one of the arbitrary taxonomies that abet practices of symbolic capital and that méconnaissance helps cover up (Bourdieu, pp. 164-165). Bryan Pfaffenberger, incidentally, published many books on computers after his Student's Personal Computer Handbook, including Democratizing Information: Online Database Technology and the Rise of End-User Searching (G. K. Hall, 1990) and Webster's New World Dictionary of Computer Terms (Que, 1999). It doesn't take much to understand that Pfaffenberger would be the last person to have been taken in by the méconnaissance of the cover to his 1984 book. Just read his brilliant piece, "Fetishised Objects and Humanised Nature: Towards an Anthropology of Technology," published in the British journal Man (23.4, 1988, pp. 236-252). His most direct connection to composition was as contributing editor to Research in Word Processing Newsletter from 1985 to 1989. He was trained in cultural anthropology and wrote his dissertation on caste, ritual, and religion in Sri Lanka, which he published in 1982. He now teaches at the University of Virginia in science and technology studies. RH, February 2006 |

As

part of Pierre Bourdieu's analysis of the practice of sociocultural

values, the notion of méconnaissance serves the critic

well. The French word does not so much mean "misrecognition"

(as Bourdieu's translator sometimes has it) as a willful refusal to

recognize. If at a party one pretends not to know or not to see a friend

whose friendship would be publicly embarrassing, that is méconnaissance.

Bourdieu applies the notion to social practices where certain obligations

and realities are disregarded and meant to be disregarded, where the

symbolic exchanges ("fake circulation of fake coin") authorize

a "deliberate oversight" (Outline of a Theory of Practice,

Cambridge University Press, 1977, p. 6). For instance, in a culture

where material interests are heavily censored (e.g., expropriation of

natural resources masquerades as a righteous war), a group "conceals

from itself its own truth" about their means of acquiring goods

(p. 22). Harvest rituals such as the contemporary USA Thanksgiving stage

public shows of unification and peace, deliberately hiding the violence

and murder that underlies the harvest itself (see pp. 132-139).

As

part of Pierre Bourdieu's analysis of the practice of sociocultural

values, the notion of méconnaissance serves the critic

well. The French word does not so much mean "misrecognition"

(as Bourdieu's translator sometimes has it) as a willful refusal to

recognize. If at a party one pretends not to know or not to see a friend

whose friendship would be publicly embarrassing, that is méconnaissance.

Bourdieu applies the notion to social practices where certain obligations

and realities are disregarded and meant to be disregarded, where the

symbolic exchanges ("fake circulation of fake coin") authorize

a "deliberate oversight" (Outline of a Theory of Practice,

Cambridge University Press, 1977, p. 6). For instance, in a culture

where material interests are heavily censored (e.g., expropriation of

natural resources masquerades as a righteous war), a group "conceals

from itself its own truth" about their means of acquiring goods

(p. 22). Harvest rituals such as the contemporary USA Thanksgiving stage

public shows of unification and peace, deliberately hiding the violence

and murder that underlies the harvest itself (see pp. 132-139).