|

CompPanels: Images from the Annals of Composition #24 Reproduction and Choice in 1953 |

|

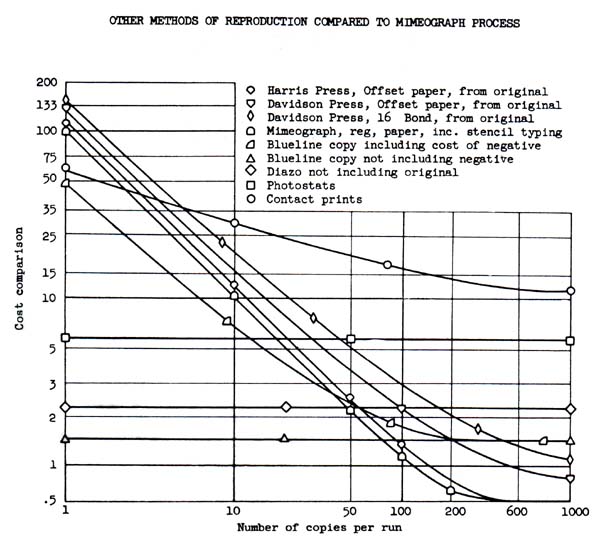

Normally reproducing words costs less money than producing them. But how much less? It depends on the method of reproduction, and on the number of copies. It's 2004 and in my department the rules are precise: For five or more copies, use the photocopier instead of the laser printer. What might have been the rules before toner and digital files? This chart gives a very precise answser. It is good for 1953; at least it was presented April that year during a conference on technical report writing, at the Catholic University of America, by Robert E. Mixson. Mixson set mimeographing as his baseline. So in 1953 if you wanted 10 copies, mimeographing would cost you about twice as much as photostating (this calculation adds in the cost of typing the mimeograph stencil). But if you needed 200 copies, photostating would cost you about four times as much as mimeographing. Mimeographing becomes more cost effective right at 14 copies. This is a very useful chart. Not very useful today, however. The tools graphed by Mixson are still around, but equipment, labor, materials, and methods kept on changing. In 1953, the Harris press provided top-of-the-line offset printing. The Davidson offset press was a smaller machine and sometimes businesses owned their own. Blueline printing also worked from a photographic negative but printed only in blue. Diazo printing, still the standard method for reproducing architectural designs, worked from a paper original and could print in blue or black but required a specially ventilated room because it used ammonia hydroxide vapors in the process. Finally the photostat machine was the photocopier of many offices before photocopiers became popular. About the same size as your current photocopier, the "stat" camera needed a darkroom to operate. Mixson omits photocopiers because they were not common office equipment in 1953, although Xerox had a "xerographic" machine available as early as 1950. But why does Mixson leave out ditto machines? The "spirit duplicator" was certainly ordinary equipment in 1953. Maybe he didn't consider it because the process has a limit to number of copies (each print strips away a bit of the ink). Or maybe he had bad memories, such as the times he typed a whole page before discovering that he had not removed the inner protective sleeve from the ditto master. (I could have told him, though, that in a pinch you can still get a marginal number of marginally respectable copies by running the sleeve itself through the machine.) Or maybe he had an intuition that of all these methods of print reproduction, the ditto machine—once the workhorse of the academic department—would suffer the most thorough extinction within half a century. Mixson's chart itself is reproduced in his "Reproduction of Technical Reports," in Bernard M. Fry and James Joseph Kortendick (Eds.), The Production and Use of Technical Reports; the Proceedings of the Workshop on the Production and Use of Technical Reports Conducted at the Catholic University of America from April 13 to April 18, 1953 (Washington, D. C.: Catholic University of America Press), pp. 34-49. RH, June 2004 |