|

CompPanels: Images from the Annals of Composition #14 Formats for Self-referencing: 1527 and 1991 |

|

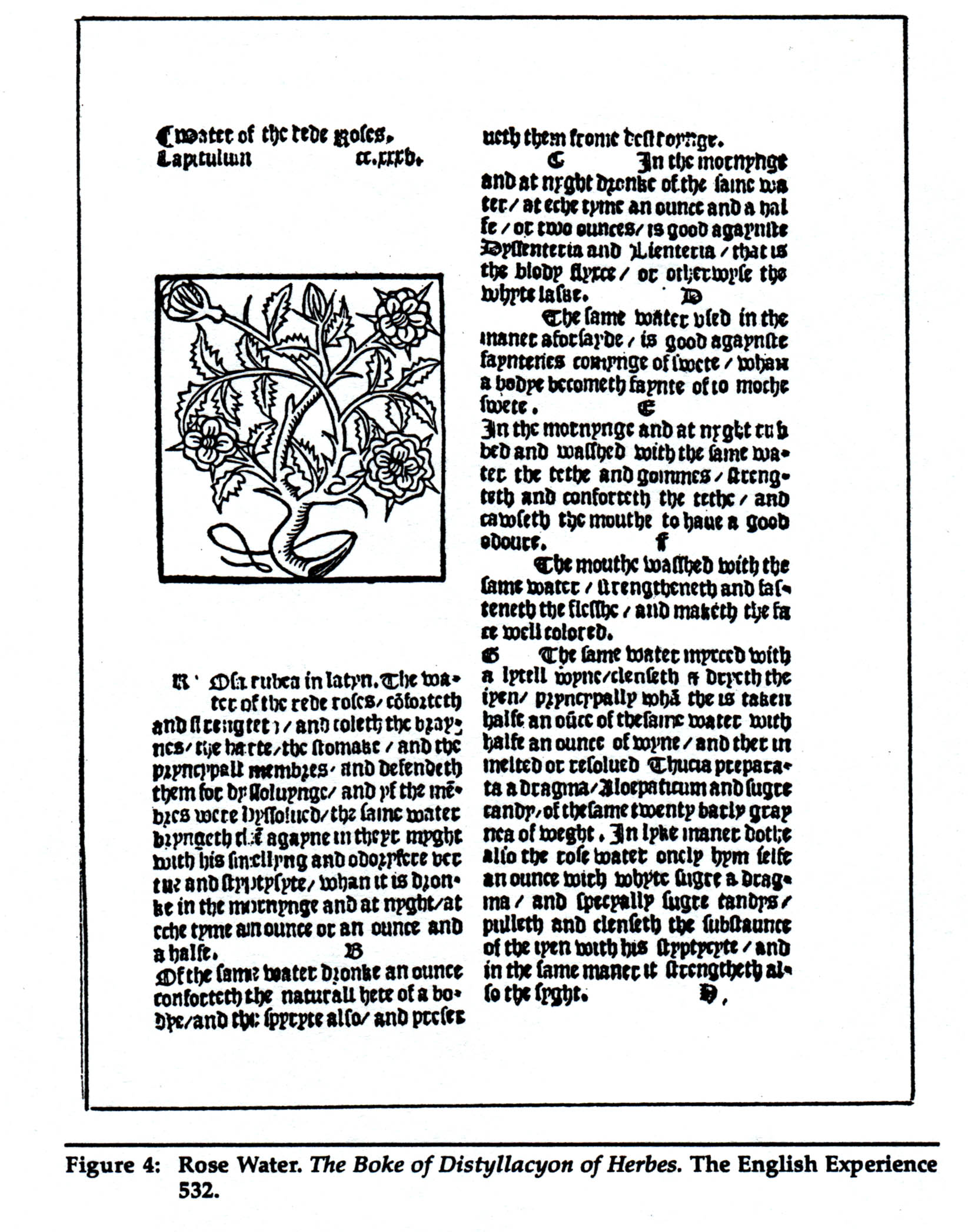

How does the format of a book

help readers find their way around it? We're so used to tables of content

at the front and page numbers in the middle and indexes at the back

that we may find it hard to imagine a book without these aids. Yet they

are absent in most of the incunabula, books printed before January 1,

1501—as they are absent in many books after that totally constructed

point in the history of books. A case in point is the famous herbal

Liber de Arte Distillandi

de Simplicibus, which qualifies as a cradle book only by

the narrowest of margins, having been first published in 1500. It was

written by Hieronymus Brunschwig (rendered also as Hieronymus Von Braunschweig

or, as the English preferred, Jerome of Brunswick). Here is one page

as it appears in an illustration from an article on text formating by

the historian of print technology, Elizabeth Tebeaux. Tebeaux analyzes

an edition of Brunschwig's herbal translated and printed by Laurens

Andrewe in 1527 and called The

Boke of Distyllacyon of Herbes. This particular page begins

a section on methods of distilling "water of the rede roses," but as

Tebeaux notes, the book's format offers the reader little help in locating

the section. At the beginning of the book there is a list of the herbs

discussed, but it is not alphabetized and each herb is followed only

by a page signature. In fact the signature, which can be seen at the

top left of the rose water page (close-up),

was mainly for the binder, to get the leaves in the right order. The

only other self-referencing format on this page is a section number

(ccxxv), which does not appear in the prefatory index, and the division

of the discussion into parts or paragraphs by alphabetic letters (which

spatially are not regularized). In contrast, let's locate the self-referencing formating devices on the page of Tebeaux's article, 450 years later. This is a verso, so the page number is even--found at the upper left corner (close-up). The running head identifies the journal in which her essay appears, with title (JBTC: Journal of Business and Technical Communication), volume (1991), and issue (July). In 16 characters, the reader with only this one page would be able to locate the volume from which it was torn. The caption to Tebeaux's illustration provides more ordering devices (close-up). "Figure 4" pinpoints this particular graphic in the series of illustrations used in Tebeaux's article, allowing her exact reference to it on other pages; "Rose Water" identifies the section in Brunschwig's book; and "The English Experience 532" locates the precise edition of the book, since this is the unique number assigned to it in Alfred W. Pollard's bibliography of early printed books in England (Pollard's work, of course, will be cited in Tebeaux's bibliography at the end of her article). In this one illustration of Tebeaux's article, I count eight distinct self-referencing devices. Pagewise, we are living in the age of dactylophilia--or of Pierce's indexicality. Tebeaux's piece is "Visual language: The development of format and page design in English Renaissance technical writing," Journal of Business and Technical Communication 05.3 (1991), 246-274. Andrewe's 1527 translation of Brunschwig's herbal is a delightful book, with many woodcuts and recipes for lotions and potions that use more than just herbs--"water of frogges" for the gout, or "pyssemer eggys" (he means ant eggs) for I don't know what. The Boke of Distyllacyon of Herbes can be found in your library on microfilm in Pollard's collection, or in digital form if your library subscribes to Early English Books Online. Or if you want a copy of your own (well, actually a 1597 German version published in Frankfurt on the Main), Abebooks has one for sale: $23,293.03 plus shipping. A historical footnote. Two years after Laurens Andrewe published his translation of Brunschwig, he was sued by the man from whom he had borrowed the type, caught the next Calais packet, and therewith, in a last gesture of anti-indexicality, disappears from the human annals of time. RH, December 2003 |